ARAH lay on a quilt under a tree. The darkness was all around her, but through the branches she could see one bright star. It was comfortable to look at.

ARAH lay on a quilt under a tree. The darkness was all around her, but through the branches she could see one bright star. It was comfortable to look at. ARAH lay on a quilt under a tree. The darkness was all around her, but through the branches she could see one bright star. It was comfortable to look at.

ARAH lay on a quilt under a tree. The darkness was all around her, but through the branches she could see one bright star. It was comfortable to look at.

The spring night was cold, and Sarah drew her warm cloak close. That was comfortable, too. She thought of how her mother had put it around her the day she and her father started out on this long, hard journey.

“Keep up your courage,” her mother had said, fastening the cloak under Sarah’s chin. “Keep up your courage, Sarah Noble!”

And, indeed, Sarah needed to keep up her courage, for she and her father were going all the way into the wilderness of Connecticut to build a house.

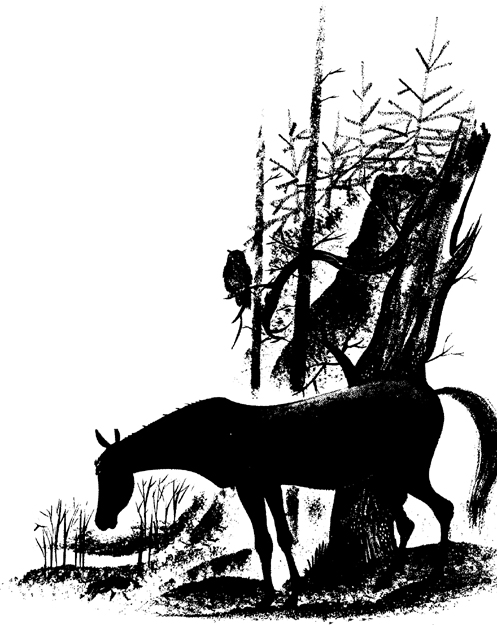

This was the first night they had spent in the forest — the other nights they had come to a settlement. Thomas, the brown horse, was tied nearby. He was asleep on his feet. Against a tree Sarah’s father sat, his musket across his knees. Sometimes he nodded, but Sarah knew that if she called to him he would wake. Suddenly she had a great need to hear his voice, even though she could not see his face.

“Wooo—oooh!” Such a strange sound from a nearby tree.

“Father?”

“An owl, Sarah. He is telling you goodnight.”

Another longer, louder sound, a stranger sound, as if someone were in pain.

“Father?”

“A fox, Sarah. He is no bigger than a dog. He is calling to his mate.”

Sarah closed her eyes and tried to sleep. Then came a sound that made her open her eyes and sit right up.

“FATHER!”

“Yes, Sarah, it is a wolf. But I have my musket, and I am awake.”

“I can’t sleep, Father. Tell me about home?”

“What shall I tell you, Sarah?”

“Anything—if it is about home.”

Now the howl of the wolf was a little farther away.

“You remember how it was, Sarah, the day I came home to tell of the land I had bought? You were rocking the baby in the cradle . . .”

“And the baby would not sleep.”

“And your mother said . . .”

“You know I cannot take the baby on a long journey. She is so young and she is not strong.”

Sarah could see her worried little mother, bending over the cradle, clucking and fussing like a mother hen.

The wolf was farther away, but still one could hear it.

“And you said . . .”

“I said, ‘I will go and cook for you, Father.’”

“It was a blessing the Lord gave me daughters, as well as sons,” said John Noble. “And one of them all of eight years old, and a born cook. For Mary would not come, nor Hannah.”

“No,” said Sarah, her voice sounding a little sleepy. “Hannah—would—not—come—nor Mary. It is good—I—like—to cook.”

But she felt suddenly and terribly lonely for her mother and for the big family of brothers and sisters. John . . . David . . . Stephen . . . Mary . . . Hannah . . . three-year old Margaret . . . the baby. . . And—could she really cook? She had never made a pie. But—maybe—you—don’t—need—pies—in—the—wilderness. Keep—up—your—courage—Sarah—Noble. Keep—up. . . . And holding tightly to a fold of the warm cloak, Sarah was asleep.

Now the wolf was very far away. But Thomas, who had raised his head when he heard it, still stood with his ears lifted . . . listening.

And Sarah’s father sat there, wondering if he should have brought this child into the wilderness. When the first light of morning came through the trees, he was still awake.