Chapter 16

Streamlining Your Work in Photoshop

IN THIS CHAPTER

Working with Actions and the Batch command

Working with Actions and the Batch command

Using the new Search panel

Using the new Search panel

Creating contact sheets and PDF presentations in Photoshop

Creating contact sheets and PDF presentations in Photoshop

Scanning multiple images in one pass

Scanning multiple images in one pass

Scripting in Photoshop

Scripting in Photoshop

A lot of the work that you do in Photoshop is fun — experimenting with filters, applying creative adjustments, cloning over former in-laws, that sort of thing. A bunch of your work, though, is likely to be repetitive, mundane, and even downright boring. That’s where automation comes in. If a task isn’t fun to do, if you need to speed things up, or if you need to ensure that the exact same steps are taken time after time, automation is for you.

I begin the chapter with a look at Photoshop’s Actions and the Batch command, which enable you to process many files automatically. I’ll then introduce the new Search feature. Next, I take a look at PDF Presentation and Contact Sheet II (used to show and print multiple images on a single page). Following those two powerful features, I show you the Crop and Straighten Photos feature, a neat way to effectively scan multiple images into Photoshop in a single pass. After that, I give you a quick look at scripts, such as the very powerful Image Processor. Scripts are sort of little computer programs that you use to control your computer — Photoshop, other programs, your printer, or even an operating system itself.

Ready, Set, Action!

In Photoshop, an Action is simply a recorded series of steps that you can play back on another image to replicate an effect or technique. To choose a wild example, say that every image in your new book about Photoshop needs to be submitted at a size of exactly 1,024 x 768 pixels at 300 ppi, regardless of content. Record an Action that uses the Image Size command to change resolution and then use the Canvas Size command to expand the image to 1,024 x 768 pixels. Use that Action (play the Action) on each image before submitting it. Better yet, wait until all the images for a chapter are ready and then use the Batch command to play the Action automatically on each of them!

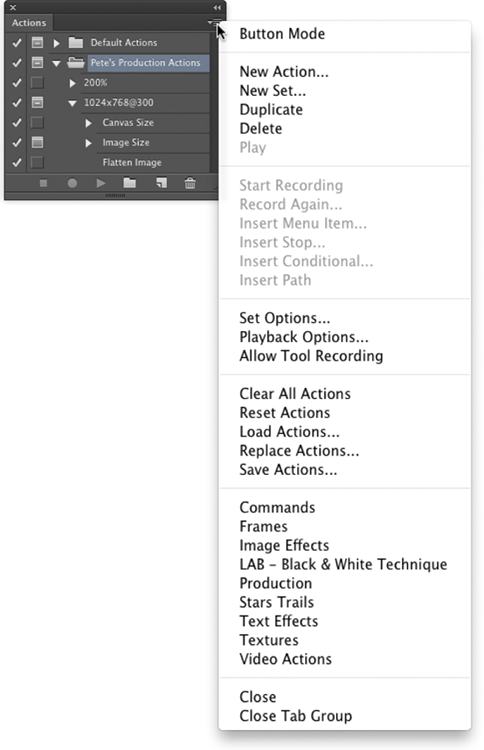

Actions and the Batch command not only streamline repetitive tasks; they also ensure precision — that every one of those images will be exactly 1,024 x 768 pixels, each and every time. But Actions also have a creative side to them. The lower part of the Actions panel’s menu (see Figure 16-1) contains sets of Actions that you can load into the panel to produce frame and border effects, text effects, and more. (The content of your Actions panel menu will differ from what’s shown in Figure 16-1.) You can also purchase collections of Actions from commercial sources.

To work with an Action, open an image, select the Action in the Actions panel, and then click the Play button at the bottom of the panel. (The three buttons to the left use the near-universal symbols for Stop, Record, and Play; the three to the right use the standard Adobe symbols indicating New Set, New Action, and Trash. Refer to Figure 16-1.)

Any step in the Actions panel that doesn’t have a check mark in the left column is skipped when you play the Action. Any step that has a symbol visible in the second column (the Modal Control column) pauses when you play the Action. Click in the second column when you want the Action to wait for you to do something. Perhaps you’ll click in that column next to a Crop step so that you can adjust the Crop tool’s bounding box. You might click in the second column next to an Image Size step so that you can input a specific size or choose a resampling algorithm. After you make a change or input a value for that step, press Return/Enter to continue playing the Action.

Notice the Save Actions command in the panel’s menu in Figure 16-1. Remember that you have to select a set of Actions in the panel, not an individual Action, to use the Save Actions command. If you want to save only one Action, create a new set and Option/Alt+drag the Action to that set to copy it. You can also create a printable text file (

Notice the Save Actions command in the panel’s menu in Figure 16-1. Remember that you have to select a set of Actions in the panel, not an individual Action, to use the Save Actions command. If you want to save only one Action, create a new set and Option/Alt+drag the Action to that set to copy it. You can also create a printable text file (.txt) of your Actions set by holding down the ⌘ +Option/Ctrl+Alt keys when selecting Save Actions. Text versions of your Actions provide an easy reference for what each Action (and step) does to an image.

If you get hooked on Actions, you’ll also want to try Button Mode in the Actions panel menu. Each Action appears in the panel as a color-coded button. You don’t see the steps of the Action, so you don’t know whether an individual step is being skipped and you can’t change the Modal Control column, but you might like the color-coding to sort your Actions.

Recording your own Actions

The real power of Actions comes when you record your own. Sure, the sets of Actions included with Photoshop are great, and the commercial packages of Actions have some good stuff too, but it’s not your stuff. When you record your own Actions, you record the steps that work for your images, your workflow, and your artistic vision.

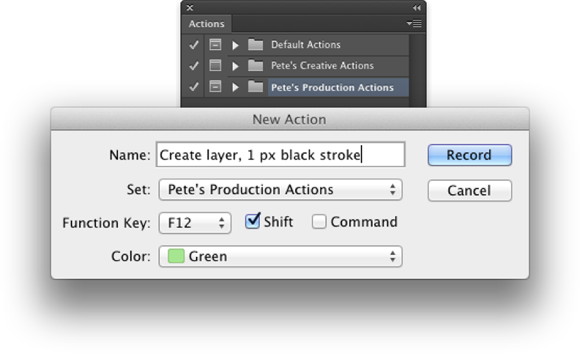

Actions can’t float free in Photoshop’s Actions panel: Each Action must be part of a set of Actions. Before beginning to record your Action, you can select an existing set or click the fourth button at the bottom of the panel to create a new set. When you have a set selected, you can then click the New Action button (second from right). Then, in the New Action dialog box that appears (as shown in Figure 16-2), assign a name (and color-code for Button Mode and perhaps choose an F-key combination as a keyboard shortcut for playing the Action) and click the Record button. From that point forward, just about everything you do in Photoshop is recorded as part of the Action until you click the Stop button at the bottom of the Actions panel. No worries, though — you can always delete unwanted steps from a recorded Action by dragging them to the Trash icon at the bottom of the Actions panel. And if you want to change something in the Action, you can double-click a step and rerecord it.

(You’ll read this again, but that little Warning symbol hopefully drives home the importance of this info.) Open the image with which you want to record the Action before you start recording. Otherwise that Open step is part of the Action and when you play the Action, it always opens that image and plays the steps on it rather than your intended image. Of course, if you want to use a special image in your Action, say a file that contains your copyright info as a graphic that you want to copy/paste into the image on which you’re working, you would indeed record the Open command within the Action (just not as the first step).

(You’ll read this again, but that little Warning symbol hopefully drives home the importance of this info.) Open the image with which you want to record the Action before you start recording. Otherwise that Open step is part of the Action and when you play the Action, it always opens that image and plays the steps on it rather than your intended image. Of course, if you want to use a special image in your Action, say a file that contains your copyright info as a graphic that you want to copy/paste into the image on which you’re working, you would indeed record the Open command within the Action (just not as the first step).

You can record most of Photoshop’s commands and tools in an Action, but you can’t control anything outside of Photoshop. (For that you need scripting, introduced later in this chapter.) You can’t, for example, use an Action to print (controlling the printer’s own print driver), copy a filename from the Mac Finder or Windows Explorer, or open Illustrator and select a path to add to your Photoshop document. Here are some tips about recording your own custom Actions:

You can record most of Photoshop’s commands and tools in an Action, but you can’t control anything outside of Photoshop. (For that you need scripting, introduced later in this chapter.) You can’t, for example, use an Action to print (controlling the printer’s own print driver), copy a filename from the Mac Finder or Windows Explorer, or open Illustrator and select a path to add to your Photoshop document. Here are some tips about recording your own custom Actions:

- Open a file first. Open the file in which you’re going to work before you start recording the Action. Otherwise, as you have been warned, the Open command becomes part of the Action, and the Action will play on that specific file every time you use it. You can, however, record the Open command within an Action to open a second file — perhaps to copy something from that file.

- Record the Close command after Save As. When you record the Save As command in an Action, you’re creating a new file on your hard drive. Follow the Save As command with the File ⇒ Close command and elect Don’t Save when prompted. That closes and preserves the original image.

- Use Percent as the unit of measure. If you need an element in your artwork to be in the same relative spot regardless of file size or shape (like a copyright notice in the lower-right corner), change the unit of measure to Percent in Photoshop’s Preferences before recording the Action.

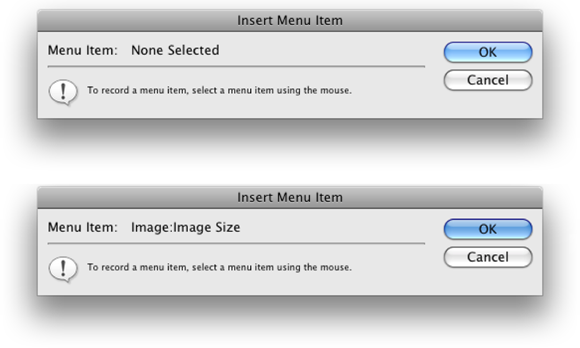

- Record/insert menu commands. When you use a menu command while recording your Action, the actual values that you enter into the dialog box are recorded, too. If you’d rather select the values appropriate for each individual image (perhaps for the Unsharp Mask filter or the Image Size command), insert the command rather than record it. When you reach that specific spot in your process, use the Actions panel menu command Insert Menu Item. (Refer to Figure 16-1.) With the dialog box open, mouse to and select the appropriate menu command; then click OK to continue recording the Action. In Figure 16-3, you see the Insert Menu Item dialog box when first opened (before a command is selected) and after I used the mouse to select the Image Size command from Photoshop’s Image menu.

- Record multiple versions of a step, but activate one. Say you want to record an Action that does a lot of stuff to an image, including changing the pixel dimensions with the Image Size command. However, you want to use this Action with a variety of images that require two or three different final sizes. You can record as many Image Size commands as you want in that one Action — just remember to deselect the left column in the Actions panel next to each of the Image Size steps except the one you currently want to use.

- Record Actions inside Actions. While recording an Action, you can select another Action and click the Actions panel’s Play button — the selected Action will be recorded within the new Action.

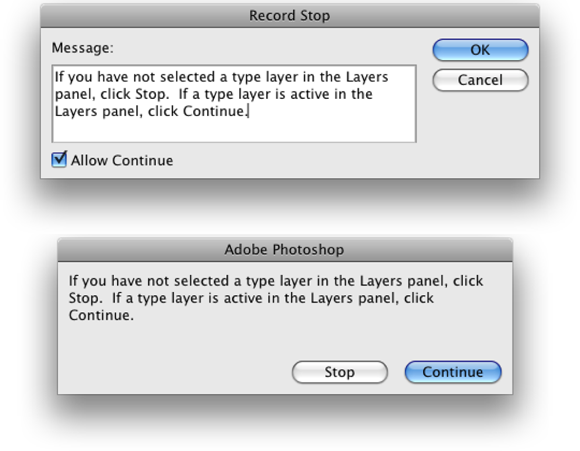

- Insert a message or warning. Use the Actions panel menu Insert Stop command to send a message to anyone who plays your Action. The message could be something like “You must have a type layer active in the Layers panel before playing this Action” with buttons for Stop and Continue. Or you could phrase it more specifically: “If you have not selected a type layer in the Layers panel, click Stop. If a type layer is active in the Layers panel, click Continue.” The more precise the message, the less confusion later. In Figure 16-4, you see the Record Stop dialog box, where you type your message when recording the Action (top), as well as a look at how the message appears when the Action is played back later (bottom).

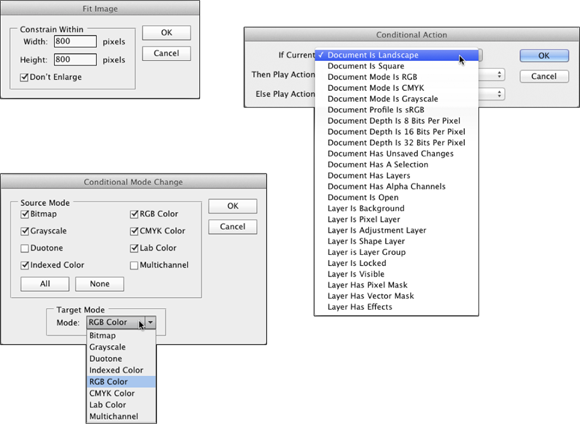

- Insert a conditional Action. If you choose the menu command Insert Conditional while recording an Action, you can choose from a list of situations (as shown to the right in Figure 16-5), and select an existing Action to play. If, for example, you need to have a flattened image for a specific situation, first record an Action by choosing Layer ⇒ Flatten Image. Then, when recording your more complex Action, insert the conditional Document Has Layers and elect to play your Flatten Image Action. If you run the complex Action on an image that’s already flattened, Photoshop will skip the Flatten Image Action specified in the conditional.

- Remember Conditional Mode Change and Fit Image. These two commands in the File ⇒ Automate menu are designed to be recorded in an Action that you might later use on a wide variety of images.

- Conditional Mode Change is very handy when your Action (or final result) depends on the image being in a specific color mode. When you record Conditional Mode Change in an Action, every image, regardless of its original color mode, is converted to the target color mode (see Figure 16-5). Say, for example, that you need to apply a certain filter in an Action, but that filter is available only for RGB images. If you record Conditional Mode Change before running the filter, the Action will play properly.

-

Fit Image specifies a maximum width and height that the image being processed must not exceed, regardless of size or shape — great for batch-processing images for the web. Fit Image maintains your images’ aspect ratios (to avoid distortion) while ensuring that every image processed fits within the parameters you specify. (See Figure 16-5.) If you need all landscape-oriented images to be 800x600 pixels and all portrait-oriented images to be 600x800 pixels, enter 800 in both the width and the height fields.

Notice the Don’t Enlarge check box in the Fit Image dialog box. If you’re prepping images for a website and reducing them to a specific size to make them download and display faster, you don’t necessarily want to enlarge some of the images, making them download slower. Disable this option when you’re trying to make all the images uniform in size, perhaps for the creation of a PDF presentation (discussed later in this chapter).

- Always record an Action using a copy of your image. Because the steps that you record in the Action are actually executed on the open file, record your Action using a copy of the original image. That way, if something goes wrong, your original image is protected.

The Actions panel menu also offers the Allow Tool Recording option. This feature enables you to record tools such as the Brush and the Clone Stamp in Actions. However, there are a few limitations. While you can record the tool, you can’t record changing its settings. If, for example, you recorded the Action using a feathered 40-pixel brush tip, you’ll need to remember to select that brush tip prior to playing the Action. In addition, the data recorded for the tool movement is device-specific. If you record the Action on one computer and play it back on a computer using a different video card and/or monitor, the results may be slightly different. Do not depend on Actions that record tool movement for precision!

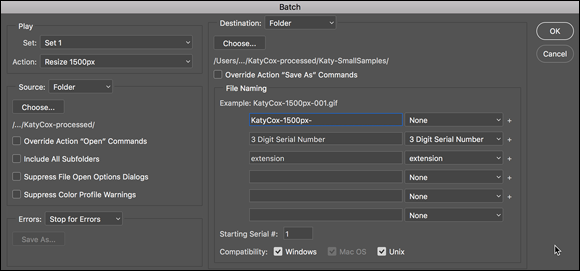

Working with the Batch command

Choosing File ⇒ Automate ⇒ Batch lets you play back an Action on a number of files. You select an Action to play and also a folder of image files to play it on; then you decide what you want to do with the files after the Action finishes with them. You can leave the images open in Photoshop, save and close them, or (much safer) save them to another folder, preserving the originals. Figure 16-6 shows the Batch dialog box and also the pop-up menu for the fields in the File Naming area. (When you select a new folder as the Destination in Batch, you must tell Photoshop how you want the new files to be named.)

You must remember three things when assigning filenames:

- Include a variable. Something must change from filename to filename. Select one of the top nine items in the File Naming section’s pop-up menu (some version of the original document name or a serial number or a serial letter). It doesn’t have to be in the first field, but one element of the filename must be different from file to file.

-

Don’t use a period (.) in any field. You can type in any of the fields (except the last one you use), but for compatibility, stick with letters, numbers, underscores (_), and hyphens (-).

Absolutely do not use a period (.) in the filename. The only period that should be used in a filename is the one that’s automatically added immediately before the file extension. Including a period earlier in a filename may make that file unrecognizable for some programs.

- You have two other decisions of note in the Batch dialog box. When you elect to suppress any Open commands in the Action, you protect yourself from poorly recorded Actions that start by opening the image with which they were recorded. However, if the Action depends on the content of a second file, you don’t want to override that Open command. Generally, you want to override any Save As commands recorded in the Action, relying instead on the decisions that you make in the Batch dialog box to determine the fate of the image.

Keep in mind that you can also select some of the images in a folder in Bridge, and then choose Tools ⇒ Photoshop ⇒ Batch from Bridge’s main menu to run an Action on just those files. The Source menu will be set to Bridge.

Keep in mind that you can also select some of the images in a folder in Bridge, and then choose Tools ⇒ Photoshop ⇒ Batch from Bridge’s main menu to run an Action on just those files. The Source menu will be set to Bridge.

Find It Fast with Search

New in Photoshop CC 2017 is the Edit ⇒ Search feature, which you can use to find a variety of items. (See Figure 16-7.) You can search for features within Photoshop, use the Learn link to search Help and tutorials, and Stock to look for images in the Adobe Stock collection. Much to the annoyance of some Photoshop users who do a lot of work with filters, Search has been assigned the ⌘ +F (Control+F in Windows). Reapplying the last-used filter now uses the shortcut ⌘ +Option+F (Control+Alt+F in Windows). And that, of course, messes up the shortcuts that open the last-used filter’s dialog box. On Mac, add the Control key; Windows doesn’t (at this time) have a comparable shortcut. However, if you go to Edit ⇒ Keyboard Shortcuts, you can switch the Last Filter’s shortcut back to ⌘ +F (Control+F in Windows), you can open the last used filter dialog box by adding the Option/Alt key.

New in Photoshop CC 2017 is the Edit ⇒ Search feature, which you can use to find a variety of items. (See Figure 16-7.) You can search for features within Photoshop, use the Learn link to search Help and tutorials, and Stock to look for images in the Adobe Stock collection. Much to the annoyance of some Photoshop users who do a lot of work with filters, Search has been assigned the ⌘ +F (Control+F in Windows). Reapplying the last-used filter now uses the shortcut ⌘ +Option+F (Control+Alt+F in Windows). And that, of course, messes up the shortcuts that open the last-used filter’s dialog box. On Mac, add the Control key; Windows doesn’t (at this time) have a comparable shortcut. However, if you go to Edit ⇒ Keyboard Shortcuts, you can switch the Last Filter’s shortcut back to ⌘ +F (Control+F in Windows), you can open the last used filter dialog box by adding the Option/Alt key.

Creating Contact Sheets and Presentations

Presentations and contact sheets are great for showing off your work. Rather than opening an image, showing it, closing, then opening the next image, you have them in a simple presentation format or, with contact sheets, multiple images on a single page. (Contact sheets are also great for printing multiple images on a single sheet of paper.)

Creating a PDF presentation

Portable Document Format (PDF), the native file format of Adobe Acrobat, is an incredibly useful and near-universal format. It’s hard to find a computer that doesn’t have Adobe Reader or another PDF-reading program (such as the Mac’s Preview), and that helps make PDF a wonderful format for sharing or distributing your images.

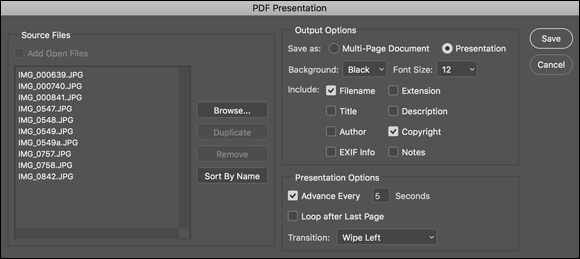

You can quickly and easily create both on-screen presentations (complete with fancy transitions between images) and multipage PDF documents (suitable for distribution and printing) by choosing File ⇒ Automate ⇒ PDF Presentation. (See Figure 16-8.)

To create a PDF presentation or a multipage PDF in Photoshop, take the following steps:

-

If the files you want to use aren’t already open in Photoshop, click the Browse button. You can click and then Shift+click to select a series of images or ⌘ +click (Mac)/Ctrl+click (Windows) to select individual images.

Hint: You must select the individual images; you can’t select only the folder.

After you click the Open button, the filenames appear in the PDF Presentation window. Drag filenames up or down to reorder them.

If, for example, you have a number of images open in Photoshop and select the Add Open Files and the files don’t open in order of filename, you can click the new Sort By Name button to re-sort the files in the left column.

If, for example, you have a number of images open in Photoshop and select the Add Open Files and the files don’t open in order of filename, you can click the new Sort By Name button to re-sort the files in the left column.

-

In the Output Options area, you can elect to create an on-screen presentation or a multipage document.

You can choose to have a white, gray, or black background and what file-related information you want on each slide or page. Electing to include the filename (and perhaps your copyright information) is a good idea when sending images to someone who needs to know the image name, say, to order prints and give you cash for them. A multipage PDF is an excellent way to share a large number of images; a presentation is a great way to show off your work.

-

Select how you want the presentation to play.

You can have the presentation automatically switch images after a given number of seconds (or opt for manual slide advance), you can have the presentation automatically rewind and begin playing again (loop), or you can pick transitions between images. Do your audience a favor and pick a single transition and stick with it — preferably one simple transition, such as Wipe Left or Wipe Right. Those too-busy transitions are the 21st-century version of PowerPoint clip art — fun to play with, but distracting to your audience.

-

Click the Save button.

You see the Save dialog box, from which you pick a location and a name and then click another Save button.

-

In the Save Adobe PDF dialog box, make things simple for yourself and choose Smallest File Size or High Quality Print from the Adobe PDF Preset pop-up menu at the top.

If you’re creating a presentation or want to create a multipage PDF from which the recipient can’t print full-size images, choose Smallest File Size. For a multipage document from which you do want the client to print great images, use High Quality Print.

-

The only other area of the dialog box that you really need to consider is Security.

You can assign a password to the file that the recipient needs in order to open and view the presentation or multipage PDF document. Alternatively, you can require no password to open the file, but rather assign a password for printing or changing the file.

- At the end of the road, click the Save PDF button to actually generate the final file.

Do you ever get annoyed by the fact that Photoshop prints only one image at a time? Are there times when you’d like to send a bunch of images to print at the same time, perhaps overnight or while you’re at lunch? Create a multipage PDF from the images and print through Adobe Reader or Acrobat, or other programs that can work with multipage PDFs, such as the Mac’s Preview.

Do you ever get annoyed by the fact that Photoshop prints only one image at a time? Are there times when you’d like to send a bunch of images to print at the same time, perhaps overnight or while you’re at lunch? Create a multipage PDF from the images and print through Adobe Reader or Acrobat, or other programs that can work with multipage PDFs, such as the Mac’s Preview.

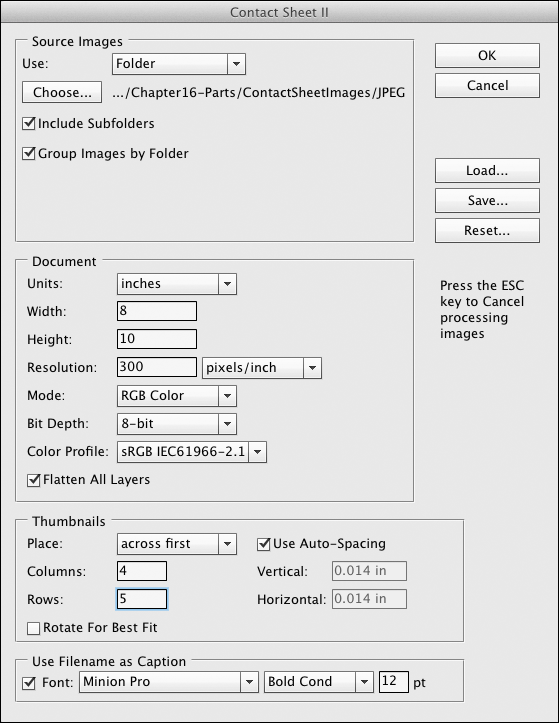

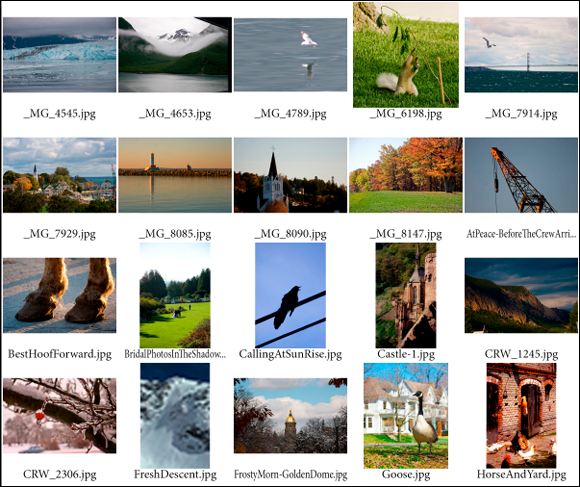

Collecting thumbnails in a contact sheet

In the old Dark(room) Ages, photographers regularly made a record of which images were on which film strips by exposing those strips on a piece of photographic paper, thus creating a contact sheet (the film strips were in contact with the sheet of paper). The contact sheet serves the same purpose as thumbnails or previews in Bridge or the Open dialog box or thumbnail images on a web page — they show which image is which. Hard copy contact sheets are useful to present to a client. You can have Photoshop automate the process for you by choosing File ⇒ Automate ⇒ Contact Sheet II. (See Figure 16-9.) The procedure is as follows:

- Select a source folder from the Use drop-down list in the Source Images area.

-

(Optional) If you want to include the images in any subfolders that might be within that folder, select the Include Subfolders check box.

The Group Images by Folder option starts a new contact sheet for each subfolder.

- Using the Units, Width, and Height options in the Document area, describe your document, using the printable area of your page — not the paper size.

-

Select a resolution.

I recommend 300 pixels per inch (ppi) if printing and 72 ppi if you’ll be slicing the image for your website (although resolution really doesn’t matter for most web browsers).

- Use the Mode drop-down list box to choose a color profile (an RGB profile unless printing to a color laser printer) and also decide whether you want to flatten all layers (which makes a smaller but less versatile file).

You can choose to have the images added to the page row by row (the second image is to the right of the first) or column by column (the second image is directly below the first). You can also choose the number of rows and columns, which determines the size of each individual image. You then need to decide whether to use auto-spacing, to calculate the spacing between images, and whether to rotate images. If your source folder has a mixture of landscape and portrait images, rotating makes sure that each is exactly the same size — although some will be sideways. If image orientation is more important than having identical sizes, don’t use the Rotate for Best Fit option. Note in Figure 16-10 that the filenames change size to match the size of the image and, as you can see at the far right of the second row, if the filename is too long, it gets truncated rather than shrinking to an unreadable size. When you have elected to include filenames as captions, Contact Sheet II lets you choose any font installed on your computer for the filenames.

If your folder is filled with portrait-oriented images, you can certainly have more columns than rows so that each image better fills the area allotted for it. For example, when printing 20 portrait images, using five columns and four rows produces larger printed images than using four columns and five rows.

If your folder is filled with portrait-oriented images, you can certainly have more columns than rows so that each image better fills the area allotted for it. For example, when printing 20 portrait images, using five columns and four rows produces larger printed images than using four columns and five rows.

Scanning Multiple Photos in One Pass

You can often save a lot of time by placing multiple photos on the glass of your scanner and scanning them all at once. You don’t need to reopen the scanner software or generate a new preview every time; rather, you just scan one big picture and make individual little pictures from it later in Photoshop. Photoshop’s File ⇒ Automate menu offers a neat timesaving feature named Crop and Straighten Photos, which generates a separate file for each photo it finds in the scan.

For best results, place the photos on the scanner’s bed with a slight gap between them. I like to place a sheet of colored paper or plastic on top of the photos, between the backs of the photos and the scanner’s lid. (See Figure 16-11.) I use paper or plastic that is a very different color from any color found along the edges of the photos. This gives Photoshop a good idea about where each photo ends and the next begins.

For best results, place the photos on the scanner’s bed with a slight gap between them. I like to place a sheet of colored paper or plastic on top of the photos, between the backs of the photos and the scanner’s lid. (See Figure 16-11.) I use paper or plastic that is a very different color from any color found along the edges of the photos. This gives Photoshop a good idea about where each photo ends and the next begins.

After the scan is complete and the image is open in Photoshop, choose File ⇒ Automate ⇒ Crop and Straighten Photos. No dialog box, no submenus — just select the command and wait a few seconds while Photoshop identifies the individual scanned images and creates a separate file for each.

Sticking to the Script

You can use AppleScript (Mac), Visual Basic (Windows), and JavaScript (both) with Photoshop. Scripts are much more powerful than Photoshop’s Actions because they can control elements outside of Photoshop itself. AppleScripts and Visual Basic scripts can even run multiple programs and play JavaScripts. You can find plenty of information to get you started in books and videos available on the web.

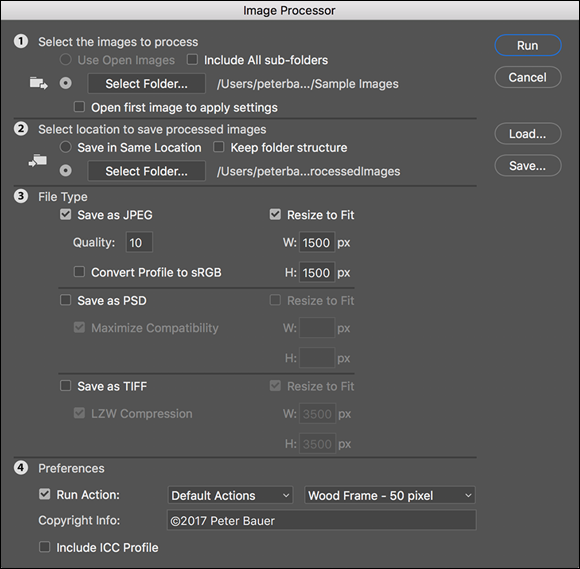

If you shoot in your camera’s Raw format, perhaps the most useful of the several pre-recorded scripts installed with Photoshop is Image Processor. (See Figure 16-12.) Choose File ⇒ Scripts ⇒ Image Processor to batch-convert your Raw images to JPEG, PSD, or TIFF — and you can even resize the images automatically while converting! (And while Image Processor is designed to work with Raw files, you can actually convert any file format that Photoshop can open.)

Image Processor is much simpler than it appears:

- Select the images to process. If the images are already open in Photoshop, great! If not, click the button and select a folder of images. If the source folder has subfolders and you want to process the images in those subfolders, select that option.

-

Choose a destination. You can save the files in the folder of origination (and even maintain the subfolder structure), or you can click the button and select a different folder in which to save the processed images.

Do not click the Select Folder button and select the source folder. If you want to keep the processed images in the same folder as the unprocessed images, simply click the Save in Same Location button. Photoshop is smart enough — most of the time — to recognize the source folder and avoid reprocessing already processed images in an endless loop, but don’t risk it.

Do not click the Select Folder button and select the source folder. If you want to keep the processed images in the same folder as the unprocessed images, simply click the Save in Same Location button. Photoshop is smart enough — most of the time — to recognize the source folder and avoid reprocessing already processed images in an endless loop, but don’t risk it.

- Select the file format and options. Each of the three file formats offers the option of resizing. JPEG offers options for Quality (the amount of compression — and associated image degradation) and to convert to sRGB (for the web or e-mail). Maximizing compatibility for PSD files ensures that the image can be seen and opened by other programs of the Creative Cloud and earlier versions of Photoshop. TIFF’s LZW compression can significantly reduce file size, without degrading the image at all.

At the bottom of the Image Processor dialog box are also the options to run an Action on the images as they’re processed, to add your copyright information to the file’s metadata (not on the image itself), and to embed the color profile in the image.

Note also the Save and Load buttons. If you set up a couple of folders, one where you dump the originals and another where you save from Image Processor, you can save your usual setup and load it whenever you need to repeat the job.

Working with Actions and the Batch command

Working with Actions and the Batch command Using the new Search panel

Using the new Search panel Creating contact sheets and PDF presentations in Photoshop

Creating contact sheets and PDF presentations in Photoshop Scanning multiple images in one pass

Scanning multiple images in one pass Scripting in Photoshop

Scripting in Photoshop

Notice the Save Actions command in the panel’s menu in

Notice the Save Actions command in the panel’s menu in

(You’ll read this again, but that little Warning symbol hopefully drives home the importance of this info.) Open the image with which you want to record the Action before you start recording. Otherwise that Open step is part of the Action and when you play the Action, it always opens that image and plays the steps on it rather than your intended image. Of course, if you want to use a special image in your Action, say a file that contains your copyright info as a graphic that you want to copy/paste into the image on which you’re working, you would indeed record the Open command within the Action (just not as the first step).

(You’ll read this again, but that little Warning symbol hopefully drives home the importance of this info.) Open the image with which you want to record the Action before you start recording. Otherwise that Open step is part of the Action and when you play the Action, it always opens that image and plays the steps on it rather than your intended image. Of course, if you want to use a special image in your Action, say a file that contains your copyright info as a graphic that you want to copy/paste into the image on which you’re working, you would indeed record the Open command within the Action (just not as the first step). You can record most of Photoshop’s commands and tools in an Action, but you can’t control anything outside of Photoshop. (For that you need scripting, introduced later in this chapter.) You can’t, for example, use an Action to print (controlling the printer’s own print driver), copy a filename from the Mac Finder or Windows Explorer, or open Illustrator and select a path to add to your Photoshop document. Here are some tips about recording your own custom Actions:

You can record most of Photoshop’s commands and tools in an Action, but you can’t control anything outside of Photoshop. (For that you need scripting, introduced later in this chapter.) You can’t, for example, use an Action to print (controlling the printer’s own print driver), copy a filename from the Mac Finder or Windows Explorer, or open Illustrator and select a path to add to your Photoshop document. Here are some tips about recording your own custom Actions:

New in Photoshop CC 2017 is the Edit ⇒ Search feature, which you can use to find a variety of items. (See

New in Photoshop CC 2017 is the Edit ⇒ Search feature, which you can use to find a variety of items. (See