Chapter 20

Ten Things to Know about HDR

The world of photography continues to evolve at an amazing pace! Not only has digital photography replaced film for just about all uses, the various Raw file formats are more and more common in both professional and high-end hobbyist photography, and even a number of smartphones. A typical camera phone now captures as many or more pixels than did an expensive pocket camera just a few years ago. Smartphones that offer an HDR option can help in some challenging lighting conditions, such as a photo of a dark room with the bright outdoors in the windows. But the smartphone’s HDR option doesn’t hold a candle to the high dynamic range images you can produce with a good camera and Photoshop’s Merge to HDR Pro.

I begin this chapter with an explanation of high dynamic range photography, give you some pointers for capturing the images that you’ll use in an HDR image, and then explain how you actually combine and use HDR photos.

Understanding HDR

HDR stands for high dynamic range. The dynamic range is the visual “distance” from black to white. By making that visual distance greater, you create a wider tonal range in the image. The world we see around us contains far more range than can be reproduced on a monitor, printed to paper, or even saved in a 16-bit image. (See Chapter 6 for an explanation of 8-bit, 16-bit, and 32-bit color.)

Consider, for example, shooting an image in a room with windows on a sunny day. If you expose your image for the content of the room, whatever is outside is blown out and completely white. (See the examples in Figure 20-1.) If you expose for the outside, the content of the room is in shadow. So, why not create an image in which the content of the room and the world outside the windows are both properly exposed?

It may be that HDR is the future of photography, the way digital has supplanted film. But probably not, until we have cameras that can capture true HDR images natively (as some smartphones can), as well as a way to better take advantage of the enhanced tonal range when printing. Is HDR something about which you should be aware, so that you can take advantage of its potential to meet difficult challenges in your own photography? Absolutely!

Remember, too, that you can open a series of Raw images shot for merging to HDR and open them together into Camera Raw. Use the menu to the right of Filmstrip (near the upper left) to Select All and then Merge to HDR. You see a preview and the Align Images and Auto Tone boxes are selected. Try all four of the Deghost options to determine which works best with your images, and then click the Merge button. (If the images were shot properly, you likely don’t need the Show Overlay option.) Camera Raw generates a

Remember, too, that you can open a series of Raw images shot for merging to HDR and open them together into Camera Raw. Use the menu to the right of Filmstrip (near the upper left) to Select All and then Merge to HDR. You see a preview and the Align Images and Auto Tone boxes are selected. Try all four of the Deghost options to determine which works best with your images, and then click the Merge button. (If the images were shot properly, you likely don’t need the Show Overlay option.) Camera Raw generates a .dng file that you can further refine in Camera Raw if desired.

Capturing for Merge to HDR Pro

To merge several exposures into an HDR image, you need to have several exposures with which to work. There are two ways to meet the challenge: You can shoot a series of exposures, or shoot one Raw image and make several copies with different exposure values.

If you want the absolutely best results from Merge to HDR Pro, keep two words in mind: manual and tripod. Those are the keys to capturing multiple exposures for use with Merge to HDR Pro. The only variable you want to change from shot to shot is the camera’s shutter speed — everything else, including focus, should remain the same. Your tripod should be sturdy and level, and a cable release is a good idea. You can use auto focus and auto exposure to set the lens and get an exposure recommendation from the camera. But then switch the lens to manual focus and set the camera to manual exposure. Before each exposure, adjust only the shutter speed.

How many exposures do you need? I recommend a minimum of three (the best exposure possible for the scene’s midtones, one “overexposed” for detail in the shadows, and one “underexposed” for detail in the highlights). Each scene differs to some degree, but you’ll want to capture as much of the tonal range as possible. It is better, however, to use seven separate exposures with Merge to HDR Pro. More than that is rarely necessary, and most scenes can be captured in five exposures.

If you are familiar with exposure values, try for a range of perhaps seven, including three below and three above the “optimal” exposure. If that’s unfamiliar territory, try shooting the optimal exposure, then taking a shot at ¼ the shutter speed of the first shot, and then taking a shot at four times the original shutter speed.

Okay, so say that you don’t have a tripod and there’s a shot that’s just crying for HDR. Set your camera to auto-bracket at the largest increment possible, set the camera to “burst” mode, get as settled as possible, frame the shot, focus, take a deep breath, let the breath out halfway, pause, then gently press and hold the shutter button. In burst mode, three (or more, depending on your camera) shots are taken as quickly as the camera can operate. In auto-bracket mode, the exposure is automatically changed for each shot. (Note that you need to set the camera to auto exposure bracketing, sometimes seen as AEB, not white-balance bracketing. Check your camera’s User Guide.)

Okay, so say that you don’t have a tripod and there’s a shot that’s just crying for HDR. Set your camera to auto-bracket at the largest increment possible, set the camera to “burst” mode, get as settled as possible, frame the shot, focus, take a deep breath, let the breath out halfway, pause, then gently press and hold the shutter button. In burst mode, three (or more, depending on your camera) shots are taken as quickly as the camera can operate. In auto-bracket mode, the exposure is automatically changed for each shot. (Note that you need to set the camera to auto exposure bracketing, sometimes seen as AEB, not white-balance bracketing. Check your camera’s User Guide.)

Preparing Raw “Exposures” in Camera Raw

Alternatively, and usually with quite good results, you can change the exposure after the fact using Camera Raw. (You’ll want to use a Raw image, not a JPEG image, for this technique.) Here’s how:

- Shoot the best exposure possible.

- Transfer the image to your computer.

-

Open the image into Camera Raw.

Make sure that Camera Raw’s Workflow Options — click the line of info below the preview (between Save Image and Open Image) — are set to 16-bit color.

- Adjust the image until it looks perfect.

- Click the Open Image button to open from Camera Raw into Photoshop.

-

Copy the image into a new file and save in the TIFF format.

Choose Select ⇒ All, then choose Edit ⇒ Copy, followed by File ⇒ Close (don’t save), and then File ⇒ New. (The preset will be set to Clipboard, so just click OK.) Choose Edit ⇒ Paste followed by File ⇒ Save As, choose TIFF as the file format, and save. Using this procedure strips out the EXIF data, making sure that Merge to HDR Pro doesn’t use the wrong exposure value.

- Reopen the original Raw file into Camera Raw.

-

Drag the Exposure slider to the left to reduce the exposure by 2.

Two is just a general guideline — watch for maximum detail in the highlights.

-

Hold down the Option/Alt key and click Open Image (Open Copy).

Opening as a copy prevents Camera Raw from overwriting the earlier adjustment in the file’s metadata.

-

Copy the image into a new file and save in the TIFF format.

Repeat Step 6, using a sequence number or other change to the filename to differentiate from the first TIFF.

- Reopen the Raw file into Camera Raw a third time.

-

Drag the Exposure slider to the right to increase the exposure by 2.

Again, two is just a starting point — you want to see maximum detail in the shadows.

- Hold down the Option/Alt key and click Open Image (Open Copy).

-

Copy the image into a new file and save in the TIFF format.

Repeat Step 6, using a third filename.

You can now use these three adjusted images in Merge to HDR, as described in the following section. The results likely won’t be as great as using a series of separate exposures, but should be better than a single exposure.

Working with Merge to HDR Pro

After you have the exposures from which you want to create your HDR masterpiece, you need to put them together using Photoshop’s Merge to HDR Pro.

You can open Merge to HDR Pro either through Photoshop’s File ⇒ Automate menu or you can select the images to use in Bridge and use Bridge’s menu command Tools ⇒ Photoshop ⇒ Merge to HDR Pro. (If you open through Photoshop, you’ll either need to open the images into Photoshop first, or navigate to and select the images to use. In Merge to HDR Pro, click the Add Open Files button. If you use Bridge, the files must all be in the same folder on your hard drive.)

Be patient with Merge to HDR Pro — it has a lot of work to do before you get to play with the combined exposures. When the calculations are done, the Merge to HDR Pro window opens (as shown in Figure 20-2).

Each of the images in the merge is shown as a thumbnail below the preview. You can deselect each image to see what impact it has on the combined exposure. (After you click the green checkmark, give Merge to HDR Pro a couple of moments to redraw the preview.) If you’re working with seven exposures and one seems to degrade from the overall appearance, leave that thumbnail’s box deselected.

By default, Merge to HDR Pro assumes that you want control over the image right away and sets the Mode menu to 16-bit color and Local Adaptation. You then have the options shown in Figure 20-2, as well as a few others, including the Curve panel (as shown in Figure 20-3).

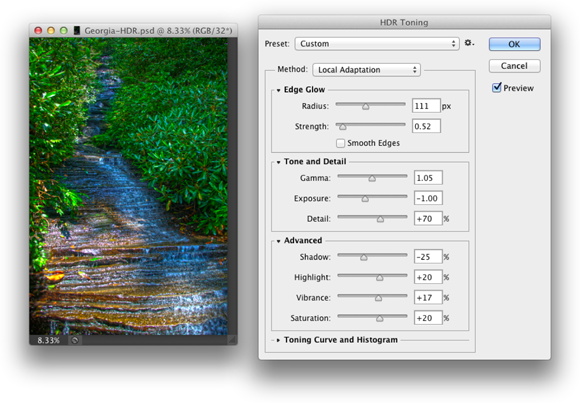

So, what are all those options you see in Figure 20-2 and Figure 20-3?

- Preset: If you have a series of similar images that require the same adjustments, you can save and load presets.

- Remove Ghosts: When you’re capturing multiple exposures, especially outdoors, moving objects in your image may have left “ghosts” behind. This option helps minimize those moving objects.

- Edge Glow: Use the Radius and Strength sliders in combination to increase the perceived sharpness of the image.

- Tone and Detail: Think of the Gamma slider as your contrast control. Dragging to the right flattens the contrast between highlights and shadows; dragging to the left increases the contrast. The Exposure slider controls the overall lightness (to the right) or darkness (to the left) of the image, just like the Exposure slider in Camera Raw. The Detail slider sharpens the smallest bits in the image.

- Advanced: Visible in Figure 20-2, the Advanced tab shares space with Curve in Local Adaptation. The Shadow and Highlight sliders here control the lower and upper parts of the image’s tonal range. For both sliders, dragging left darkens and dragging right lightens. The Vibrance slider controls the saturation of the near-neutral colors and Saturation controls all of the colors in the image. (These sliders, too, are comparable to their counterparts in Camera Raw and are discussed in more detail in Chapter 7.)

- Curve: Click the curve to add an anchor point and drag up/down or enter numeric values to adjust the tonality of the image. The Corner option produces a sharp change in the angle of the curve, which is generally not desirable. The button to the right of Corner resets the curve.

Switching the Mode menu to 32-bit color restricts your adjustment options. If you uncheck the Complete Toning in Adobe Camera Raw box, you can drag the slider to adjust the image’s white point. Clicking OK opens the image into Photoshop for any additional adjustments.

Note that 16-bit and 8-bit offer the same options, but I don’t recommend converting from 32-bit to 8-bit in Merge to HDR Pro. If you need an 8-bit version of the image, work in 16-bit, and then after perfecting the image in Photoshop and saving as a 16-bit PSD or TIFF file, use the Image ⇒ Mode ⇒ 8-Bits/Channel command to convert and use Save As (or the Export menu’s Save for Web command) to save the 8-bit copy.

Keep in mind that when the changes you make in Merge to HDR’s 16-bit mode are finalized, the unused parts of the 32-bit tonal range are discarded. Working in 16-bit mode in Merge to HDR Pro can be convenient, but you can also stay in 32-bit mode, open into Photoshop with the OK button, save the 32-bit image, and then do all the adjusting available in Merge to HDR Pro — and much more — in Photoshop. Want to fine-tune or change the image sometime down the road? Sure, why not? Simply reopen the saved 32-bit image and readjust, paint, filter, whatever, and then save again. Need a 16-bit copy to share or print? Save first as 32-bit, adjust, and then use Save As to create the 16-bit copy.

Keep in mind that when the changes you make in Merge to HDR’s 16-bit mode are finalized, the unused parts of the 32-bit tonal range are discarded. Working in 16-bit mode in Merge to HDR Pro can be convenient, but you can also stay in 32-bit mode, open into Photoshop with the OK button, save the 32-bit image, and then do all the adjusting available in Merge to HDR Pro — and much more — in Photoshop. Want to fine-tune or change the image sometime down the road? Sure, why not? Simply reopen the saved 32-bit image and readjust, paint, filter, whatever, and then save again. Need a 16-bit copy to share or print? Save first as 32-bit, adjust, and then use Save As to create the 16-bit copy.

Saving 32-Bit HDR Images

A 32-bit image can be saved in a number of file formats, including Photoshop’s PSD and Large Document Format (PSB), as well as TIFF and some specialized formats. Unless you’re sending the image to another program (perhaps when working with computer animation) or a client who has requested a specific format, stick with PSD, PSB, or TIFF.

HDR Toning

Found in the Image ⇒ Adjustments menu, HDR Toning (see Figure 20-4) is your 32-bit image adjustment master tool. It offers the same Local Adaptation, Equalize Histogram, Exposure and Gamma, and Highlight Compression options found in Merge to HDR Pro. (Each of the options is described in the “Working with Merge to HDR Pro” section, earlier in this chapter.) Although it’s also available for 16-bit and 8-bit images, HDR Toning is designed to work with the 32-bit images you create with Merge to HDR Pro. You’ll also see HDR Toning when you convert to 16-bit or 8-bit color through the Image ⇒ Mode menu.

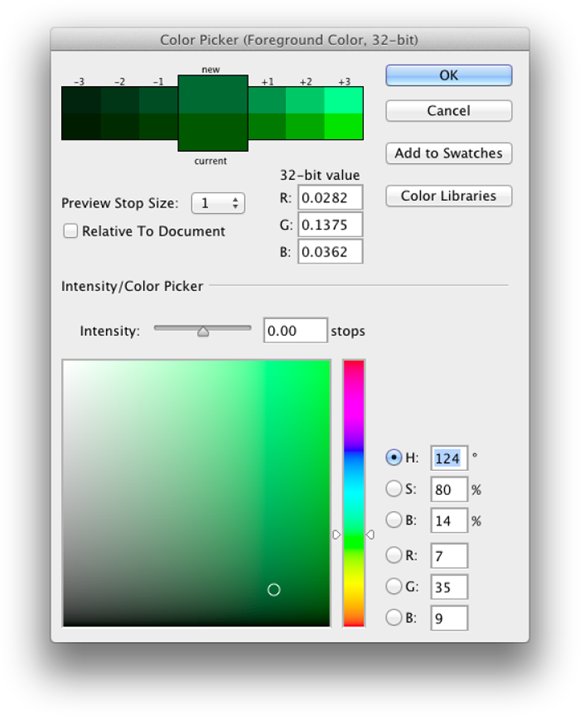

Painting and the Color Picker in 32-Bit

In Photoshop you can paint in 32-bit color — with some caveats. The Brush, Pencil, and Mixer Brush tools (but not Color Replacement) are available. The Blur, Sharpen, Smudge, and Eraser tools are also available in 32-bit color, but not Dodge, Burn, Sponge, Background Eraser, or Magic Eraser. Type layers, shapes, and paths are also at your command. You can add color to a 32-bit image with the Gradient tool, but not the Paint Bucket. And although the History Brush is available, the Art History Brush is not. The Content-Aware Move, Patch, Healing Brush, Spot Healing Brush, and the Red Eye tool are disabled. 32-bit images can have multiple layers and layer styles, too. Be aware, too, that not all blending modes are available in 32-bit color. Normal, Darken, Multiply, Lighten, Difference, and about a dozen less commonly used blending modes are enabled for tools and layers.

Working with painting tools and gradients requires a way to define color in 32-bits. When you open the Color Picker while working with a 32-bit image, you’ll see something different. In Figure 20-5, the 32-bit Color Picker shows some additional features. In addition to working with HSB and RGB fields, color is defined with the Intensity slider. Think of “intensity” as “exposure.” It permits color values that go beyond RGB’s 255/255/255. Define the color and choose how light or dark the exposure is — it’s sort of a fourth dimension of color definition.

The bar at the top shows the last-selected color below and the current selection above. You can click any of the six previews to the left or the six to the right to jump to that color. You control how different each of the 12 previews is from the current color with Preview Stop Size.

Filters and Adjustments in 32-Bit

The list of filters available in 32-bit color is even shorter than the list for 16-bit color found back in Chapter 15. The Filter Gallery, Adaptive Wide Angle, Camera Raw, Lens Correction, Liquify, Vanishing Point, and many other filters won’t work in 32-bit color, but you do have the key Blur and Sharpen filters, as well as Add Noise, Clouds and Difference Clouds, Lens Flare, Emboss, High Pass, Maximum, Minimum, and Offset. Don’t forget that 32-bit images can be converted to Smart Objects to apply Smart Filters!

The only adjustment layers that can be added to 32-bit images are Levels, Exposure, Hue/Saturation, Photo Filter, Channel Mixer, and Color Lookup, along with New Fill Layer’s Solid Color, Gradient, and Pattern. In the Adjustments menu, you’ll also find HDR Toning and Desaturate at your service.

Selections and Editing in 32-Bit

Not surprisingly, the Rectangular Marquee, Elliptical Marquee, Single Row, Single Column, Lasso, and Polygon Lasso tools are available when working in 32-bit color because they simply create selections around pixels. Also not surprising is the unavailability of the Magnetic Lasso tool because it works its magic based on identifying differences between neighboring colors. And, on the subject of magic, the Magic Wand is also out of commission when working in 32-bit color, but you can work with the Quick Selection tool in your HDR image.

And after you have made your initial selection, you’ll find that Select and Mask and Select ⇒ Focus Area are fully functional in 32-bit color, as are the Select ⇒ Modify commands and Transform Selection. You can also save and load selections (alpha channels) and work in Quick Mask mode in 32-bit images.

Printing HDR Images

Okay, well, you can’t really print the entire tonal range of a 32-bit image — no printer (or paper) can handle the range. In fact, you can’t print an image in 32-bit color at all from Photoshop (the Print and Print One Copy commands are disabled). What you can do is print a 16-bit (or 8-bit) image that has outstanding highlights, outstanding shadows, and outstanding midtones.

After saving the 32-bit original, use Photoshop’s Image ⇒ Mode ⇒ 16-Bits/Channel command to convert to 16-bit color (using Local Adaptation, as described earlier in this chapter). After changing the color depth, choose Image ⇒ Image Size to set your desired print size. You can either deselect the Resample check box and enter your desired print dimensions, letting Photoshop calculate the new resolution, or you can use the Resample option and input both the print dimensions and resolution. The resampling algorithm should be set to Automatic or Preserve Details, not Nearest Neighbor or Bilinear, neither of which is appropriate for most photos. (Those are your only four options when resampling a 32-bit image.)

When the image is ready, open Photoshop’s File ⇒ Print window. Choose the printer and click the Print Settings button to set up the printer. Choose the specific paper on which you will be printing and disable the printer’s color management. Choose the printer’s resolution and — if your printer has the capability — select 16-Bit Output.

To the right in Photoshop’s Print dialog box (as shown way back in Figure 4-11), make sure that Photoshop is managing colors and that you have selected the printer’s own profile for the specific paper on which you are printing. Generally, you should use the Relative Colorimetric rendering intent and Black Point Compensation. (Note that if your print is way too dark, Black Point Compensation should be disabled.)

You need to make all of the printer-specific choices by clicking the Print Settings button before clicking the Print button. If you want to save this 16-bit version of the image, use Save As to create a new file. Using the Save command would overwrite the 32-bit original HDR image.

You need to make all of the printer-specific choices by clicking the Print Settings button before clicking the Print button. If you want to save this 16-bit version of the image, use Save As to create a new file. Using the Save command would overwrite the 32-bit original HDR image.

And there you have it — ten things you should know about HDR. You’re now ahead of the curve and ready for the Next Big Thing in digital photography!

On behalf of everyone involved with the production of this book, let me say thanks for coming along for the ride. We wish you peace, love, health, and happiness!

Remember, too, that you can open a series of Raw images shot for merging to HDR and open them together into Camera Raw. Use the menu to the right of Filmstrip (near the upper left) to Select All and then Merge to HDR. You see a preview and the Align Images and Auto Tone boxes are selected. Try all four of the Deghost options to determine which works best with your images, and then click the Merge button. (If the images were shot properly, you likely don’t need the Show Overlay option.) Camera Raw generates a

Remember, too, that you can open a series of Raw images shot for merging to HDR and open them together into Camera Raw. Use the menu to the right of Filmstrip (near the upper left) to Select All and then Merge to HDR. You see a preview and the Align Images and Auto Tone boxes are selected. Try all four of the Deghost options to determine which works best with your images, and then click the Merge button. (If the images were shot properly, you likely don’t need the Show Overlay option.) Camera Raw generates a

Keep in mind that when the changes you make in Merge to HDR’s 16-bit mode are finalized, the unused parts of the 32-bit tonal range are discarded. Working in 16-bit mode in Merge to HDR Pro can be convenient, but you can also stay in 32-bit mode, open into Photoshop with the OK button, save the 32-bit image, and then do all the adjusting available in Merge to HDR Pro — and much more — in Photoshop. Want to fine-tune or change the image sometime down the road? Sure, why not? Simply reopen the saved 32-bit image and readjust, paint, filter, whatever, and then save again. Need a 16-bit copy to share or print? Save first as 32-bit, adjust, and then use Save As to create the 16-bit copy.

Keep in mind that when the changes you make in Merge to HDR’s 16-bit mode are finalized, the unused parts of the 32-bit tonal range are discarded. Working in 16-bit mode in Merge to HDR Pro can be convenient, but you can also stay in 32-bit mode, open into Photoshop with the OK button, save the 32-bit image, and then do all the adjusting available in Merge to HDR Pro — and much more — in Photoshop. Want to fine-tune or change the image sometime down the road? Sure, why not? Simply reopen the saved 32-bit image and readjust, paint, filter, whatever, and then save again. Need a 16-bit copy to share or print? Save first as 32-bit, adjust, and then use Save As to create the 16-bit copy.