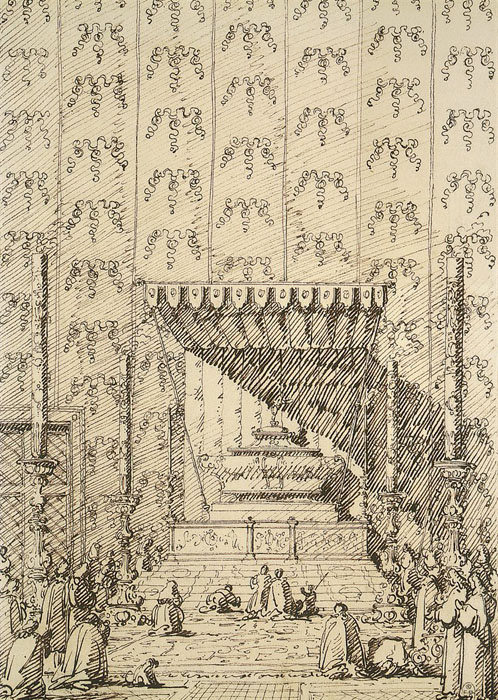

143. An Altar in the North Transept of San Marco, c. 1735.

Pencil and ink, 26.9 x 18.8 cm.

The Royal Collection, London.

Next, we find the marriage ceremony with the sea, the departure for the Lido, the symbolic rites, the return to the Saint Nicolas Church station, the Fat Thursday celebrations, the games of Herculean strength in front of the Doges’ Palace balcony, the splendid Corpus Christi procession on the Piazza and other functions and pilgrimages in which the doge took part in a robe of cloth of gold and accompanied by a State military corps and foreign ambassadors. The lively and varied colours of the costumes as well as the luxurious gondolas lend a wonderful brilliance to all these formal activities. These activities became so frequent that their required attendance constituted one of the diplomats’ most time-consuming obligations. During those days, the gondoliers in the service of the State, so proud of their livery that they did not do any of the rowing themselves, hired small boats filled with musicians to tow their vessels. Guardi sometimes presented these parades in front of Saint Barnabas’ Church, where the doge, preceded by the insignias of his coronation, returned on Easter Day, and sometimes on Santa Maria della Salute’s steps, where the people commemorated their deliverance from the plague.

Guardi serves as a link, so to speak, between Canaletto and Longhi. The first two artists display their city’s exterior mask. The third offers the onlooker information that is more intimate and more precise. One can hardly separate this artist from the others; even less can one exclude him from this gallery of masters in which he is one of the most spiritual and alluring.

During his lifetime, Pietro Longhi was as much in vogue as Guardi. Like him, he was less well-known and more appreciated in France than he was in England. A student of Balestra, and later Crespi, he devoted himself to painting contemporary scenes and to depicting the theatrical farces for which his two countrymen had designed stage sets.

His fifteen canvases on exhibit at the Correr Museum in Venice are easily recognizable because of his skilful touch and delightful use of colours. A bit of a superficial observer and a humorist with little depth, he admirably grasped Venetian society’s general tone. Without being a thoughtful poet in the style of Watteau, without achieving the artistic behaviours or the awareness of Chardin, his style is still somewhat reminiscent of these two. But he is not the equal of either – far from it. He frequented gatherings held at nobles’ residences, gaming rooms and cafés. No-one could better depict the masked characters with the allure of their mystery under the ample folds of cloaks. He was the favourite painter of knights and coquettes, so forgetful of their ancestry, of patricians coiffed with enormous wigs, and of young women in soft grey or pale yellow dresses. How he brought all of those queens of the boudoir to life, with their smiling, mocking faces listening attentively for compliments, with their gowns made of typical Venetian fabrics and with their little three-cornered hats carefully poised on top of their powdered hair! How he accentuated the aristocratic anxieties stuffed into their waistbands, the fineness of their ankles and wrists! None is more local, not only in the expressions of his characters, but also in all the accessories surrounding them.