CHAPTER 8

Dipped Candles

Dipping is probably the oldest method of candlemaking in the world. There is some evidence that the ancient Romans made dipped candles. And, aside from the newer method of container candles already described, dipping is perhaps the simplest and easiest method by which to make candles.

Dip Your Wick

Actually, a dipped candle is nothing more than a wick that has been primed—that is, a wick that has been first dipped into hot wax to eliminate air bubbles—and then re-dipped into the wax several times so that the wax forms a thick coating around the wick. As the wax drips off the dipped candlewick, it naturally forms a tapered shape. Dipped candles can be made any diameter the candlemaker chooses, although commercial dipped-type candles are made in standard sizes (with which we are familiar) to fit into standardized candleholders. Tapers are generally made ½” or 7/8 ” in diameter at the base because most purchased candleholders come in these sizes. Exceptions are birthday candles (to be stuck in the cake icing or fitted on special holders with points), and Danish tapers, which are only ¼” in diameter.

What is a dipped candle?

Dipped candles are made a pair at a time by repeatedly dipping a double loop of wick into molten wax. Dipped candles have a pleasing tapered shape. When done by hand they are uniquely beautiful. No factory-made taper can match them.

The simple process of building up wax in layers on a wick creates the lovely tapered shape—without any effort on the part of the candlemaker! However, you can manually effect the dipped candle’s shape while the candle is still warm. (We’ll discuss that in detail later.)

From Labor to Love

At today’s popular Renaissance Fairs, candle dipping is a big attraction, as it is at the town of Colonial Williamsburg. There, you can watch—and it’s fascinating to see—the women methodically dipping racks of wicks that will become tapered candles. If you visit Williamsburg, you’ll learn that Colonial women dipped candles as part of their domestic work. Every Colonial home was the producer of all things needful to life, including candles. Candlemaking was not a hobby then—it was a labor assigned to the housewife. And a backbreaking, smelly, greasy task it was. Yes, today candlemaking can be fun—and a rewarding hobby. But back then it was pure work, and lots of it.

For a long time, candles were made only of animal fat, and housewives collected every scrap after butchering and cooking of meats was completed. These precious fats were hoarded carefully, protected in covered crocks. At candlemaking time, the fat was melted down and the dipping process began.

Fortunately for early American women with the wherewithal to get them, there were other candlemaking materials available to them, besides ones available in Europe. New England gave them bayberries, which have a heavenly scent—quite a change from the stinky animal-fat candles. Bayberries were introduced to the Colonial women by their Native American neighbors, who also showed them how to get the wax out of the berries.

As you realize by now, another source of candle wax was beeswax, and many farm families raised bees, primarily for their honey and their pollination work, but also to get the sweet-smelling beeswax. Lucky was the Colonial farmer with a hive or two of bees! (Always think twice before you swat a bee—they are beneficial insects!)

In all probability, the technique of dipping was developed from the earliest form of candlelight we know, the “rush dip.” This was made by dipping long stalks of dried grass repeatedly in melted tallow (animal fat). These were then lit and used for light both outdoors and indoors.

Today, most dipped candles are made of paraffin, which is sometimes mixed with various additives, like stearic acid. The more expensive tapers available commercially may be a blend of paraffin and beeswax. Pure beeswax tapers are rarely available, but recently I have noticed some upscale mail-order catalogs are offering pure beeswax pillar candles. Beeswax needs no scent. It gives off a delightful fragrance of honey; depending on what diet the bees have had, the honeyed scent will vary slightly, from clover to wildflower.

The Skinny on Dipping

The basic dipping technique is simplicity itself. Find a can that is 2” taller than the desired length of the candles, and use it to melt wax in a pot of hot water. Ordinarily, candles are dipped in pairs, which means that one wick supports two candles. The wick is therefore cut long enough to accommodate the length of two candles. You will actually dip one wick, but hold the middle part above the wax, which is what makes the pair.

Each end of the wick is weighted, so that it will drop to the bottom of the wax receptacle. The weights also serve to keep the wicks straight in the wax bath until enough layers have been built up so that the candle itself is heavy enough to hang straight. The pair of candles is held apart with a rod, which prevents them from making contact in the hot wax and adhering to each other.

Sound easy? Let’s look at this technique more closely.

Gather Together

Before you begin, assemble all of your materials and equipment. If you are going to make a quantity of dipped candles, cut all of your wicks in advance and lay them out. Prime them and allow to harden before beginning the dipping process. You will need to have the following materials on hand:

Wax

Beeswax

Stearic Acid

Wick(s)

Colorant(s)

Scent(s)

Double-boiler setup or concealed-element heater

Thermometer

Can for dipping, at least 2” taller than the length of the candles you plan to make

Rod or dowel

Bucket

Small weights

Sharp knife

Nylon pantyhose (for polishing finished candles)

The recommended length of primed wick is 24” for each pair of candles you plan to make. A medium sized wick is recommended, such as 1/10 square braid, or 30-, 36-, or 42-ply flat braid. Again, experiment and keep notes. If you are using 50 percent or more beeswax, the wick should be increased by one or more sizes according to the diameter of the candle. Read the manufacturer’s instructions carefully.

Use the knife for slicing off the bottoms of the candles when finished. (When doing this, take care not to mark your newly made candles with fingerprints!)

The dowel is used to hold candles for dipping (although you can do this with your fingers, a “spacer” is a good idea.) A coat hanger works fine. You’ll also need something to hang drying candles on, such as hooks, nails, or pegs. For quantity candlemaking, you can use a frame.

The bucket will be useful for holding sufficient water in which to submerge the finished dipped candles. Washers, nuts, or nails are suggested to use as weights to tie at the ends of the wicks to hold them straight while dipping.

Wax Formulas for Dipped Candles

As with most candlemaking, there are no hard-and-fast rules about wax mixtures. The important factor in whether a candle will burn well is the relationship among the wax mixture’s melting point, the finished candle’s diameter, and the wick type and size. Ask yourself what you want to achieve with your dipped candles. Do you want long burning time? Do you want a slim, elegant shape? How are you going to use the candles—for a special occasion party or everyday home dining?

Here are some options for waxes used in dipping:

Pure beeswax. See “Create a Pure Beeswax Dipped Candle” later in this chapter.

Beeswax mixed with paraffin. Proportions are optional.

Paraffin, stearic acid, and beeswax. Proportions can vary. Try twice as much paraffin as stearic acid, with 1/3 as much beeswax, i.e., 6 pounds paraffin/3 pounds Stearin/1 pound beeswax.

Paraffin, with stearic acid (usually 10 percent). Pure paraffin is not advisable as it generally needs stearin to hold a shape.

Keep notes to see what works best for you. Make a test pair before going on to make quantities using the same formula. Add color and scent as you wish to any of the suggested wax mixtures. Again, experimentation is the key to success. Always make a test candle, and always keep notes of the amounts and kinds of colorants and scents you use in your wax formula.

Three sets of two pairs of 10” x 7/8” tapers require approximately 6 pounds of wax. With a large dipping can, you will need more in order to submerge the wicks entirely. If wax is left over, pour it into lined, shallow baking pans to cool and reuse.

Take the Plunge

Begin by measuring the wicks. Each wick should be twice the length of the candle you are planning to make (in pairs) plus an additional 4”, to allow the candles to be held apart when being dipped. You’ll find that while being dipped, the candles have a natural attraction to each other—they seem to want to be just one candle! To prevent them from sticking together, you have to take extra care as you lift them in and out of the melted wax. This can take a bit of practice if you use your fingers, but you can also use a small piece of cardboard or a rod as a spacer/holder to keep the forming candles separated. If you are new to candle dipping, experiment with various methods of holding the pairs of candles apart before attempting to dip a quantity of pairs.

Tie a small weight—for example, a washer, a nut, a nail, or a curtain weight—to the end of each wick you are going to dip.

Although you can dip each pair just by holding it with your fingers, that can be cumbersome, especially if you want to make more than one pair at a time. If you are making a single pair of dipped candles, you can take a small piece of cardboard, about 2” square, and cut ½” slits on either side of it to make a channel to hold the wick. You then hold the cardboard “spacer” with your fingers to do the dipping.

Luckily, there are several simple dipping frames you can improvise for dipping multiple candles. One is a slender rod or dowel. Loop the upper ends of the wick around it and tie them securely. You can use a heavy coathanger (one that won’t bend with the growing weight of the candles as they are being dipped). A metal rod, such as those used to hang curtains, will work well. There’s a type of curtain rod called a “tension rod,” which has two pieces that fit together with a spring in between. You can use just one piece. These rods are very sturdy.

Next, prepare your double-boiler setup for heating the wax—and remember that your wax receptacle must be 2” taller than the length of the candles you are going to make. Fill the bottom pan with water. Put the dipping can in the water receptacle (it can be a large saucepan). Cut up or break your wax into chunks and place them into the dipping can. Heat the water slowly to begin the melting process. Stir occasionally. Put in any additives you are using in addition to stearin, such as colorants and scents. Mix well to distribute these elements throughout the wax.

The Importance of Temperature Control

Keep a constant check on the temperature of the wax with your thermometer, and leave the thermometer in the wax while you are working. This will tell you how long the wax maintains the correct temperature before it needs reheating. At 160° Fahrenheit (or whatever other melting point your wax has, whether it is above or below this temperature), lower the heat under the pot of water.

Wax shrinks as it cools, so each dip should be in the same temperature of wax. Use your thermometer to check temperature. The candle should cool before re-dipping, but it should not be cold. Your work area should be normal room temperature. You may want to use a water bath to cool the candles between each dipping.

Using Colorants

There are two ways to make a colored dipped candle. You can add color to the wax and have the candle colored throughout. Or, you can “overdip,” a process we will describe in full later, by dipping white candles into colored wax for the last few dips, just enough to coat the white wax with color.

If you want to dip in colored wax, do not add too much coloring agent at first. If after you have made a pair of candles you want to intensify the color, you can always add more colorant to the remaining wax. Again, keep notes of how much colorant you use to which proportion of waxes.

Candle Colorant Technical Papers

You can order several fairly inexpensive technical papers on dyes and pigments from the National Candle Association. Available are the following:

If you want to get into candlemaking at the advanced level, or if you simply want to color and scent your basic candles, these are worth your consideration and could, in the end, save you money and a lot of trial-and-error candlemaking.

Be careful what you put in your wax mixture. Don’t ever use lipsticks or house paint for a coloring agent. Stay away from crayons, unless they are made of wax. To stay on the safe side of this nasty problem, always use color material that is made especially for candlemaking.

Ready to begin?

Hold a length of wick in the center (looped over your fingers) and dip both ends into the melted wax, keeping your fingers 2” above the melted wax. Leave the wick in the wax for about three seconds. Remove and allow to cool on a holding peg for about three minutes. Don’t touch the candles while they cool down. If the first layer of wax is smooth when cool, continue the dipping and cooling process until you have produced candles of the thickness you desire.

You can speed up the cooling process in between dips by submerging the growing candle into a water bath. However, if you use this cooling method, make absolutely sure that all the water residue has evaporated from the surface of the candles. If you dip candles that have water on their surface, you will get wax-covered water bubbles in the finished candles. These cause candles to sputter when burned, and they mar the finished appearance of the candles.

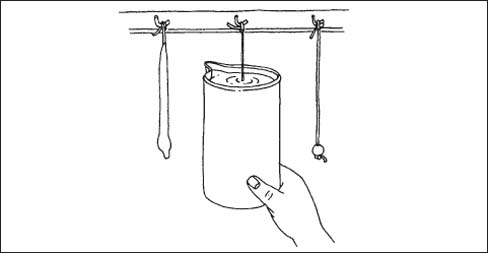

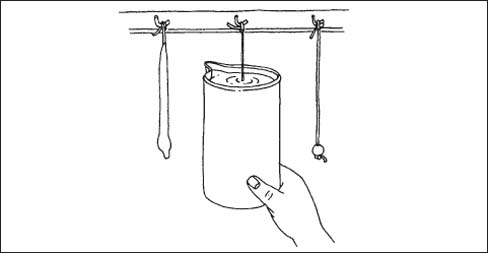

Dipping candles

Before re-dipping, make sure the previous layer is cool. Dip the candles in the melted wax quickly, to the same level as the first dip. Pull them out slowly and steadily. You should begin to see a waxy buildup on the wick by the third dip. If the wax isn’t adhering properly to the wick, let the wax cool a bit (about 5° Fahrenheit) and re-dip the wick until you see the wax beginning to grow.

Your dipping can will initially contain much more wax than you will actually use for making the many layers of the final candles. However, because you are taking wax out of the dipping can, you will need to replenish your supply of wax frequently. The best way to do this handily is to keep a second double-boiler setup going with a supply of extra wax for refilling the dipping can. In order to be consistent, remember to first determine the exact wax formula, including color and/or scent, that you want to use for all of the candles you are dipping in one session.

Growing Your Dipped Candles

The dipping-and-drying process can take fifteen to thirty dips, depending on the thickness you want the candles to be. This requires a certain amount of patience, but it is quite fascinating to watch the candles grow into their lovely tapered shapes as you work with them. As your candles begin to accumulate layers of wax, the cooling time in between dips will increase. Make sure the candle is cooled each time before you re-dip. Also, it’s best to rotate the dipping frame so that you can see the opposite sides of the growing candles as you dip to make sure you are getting a smooth effect all around.

Progression of dipped candles

After several dips, the candles will have thickened enough to serve as their own weights. At this point, before doing your final dips, take the sharp knife and slice off the bottoms of the candles where the weights are embedded in the wax. When cutting off the bottoms, make sure the candles are cool and hard enough not to be imprinted with your fingertips. Do this as cleanly as possible so that the candle base will be finished nicely. If you don’t get it quite right, you can always repeat the process later. Save the candle ends with the weights in them to remelt and use later on. You can achieve a shiny surface on your dipped candles by submerging them into cool water after the final dip. After doing this, hang them up to dry for one hour or more. Store newly made candles laid flat and away from direct sunlight.

And don’t forget to take notes. This is an all-important step for the candlemaker to be able to repeat successes and avoid future failures.

For an ultra-smooth surface, on the final dip increase the heat of the wax to 180° Fahrenheit. After the last dip, lower the heat immediately so as not to overheat the wax. And always watch your thermometer carefully as you work.

Reverse Dipping

Although this reverse process of bringing the wax to the taper strikes me personally as a bit cumbersome, it is the preferred method for some experienced candlemakers. Instead of dipping the wick into the wax, reverse the procedure by raising the container to the wick. This allows you to coat each wick, one after the other, pausing only to reheat the wax when it cools off.

If you are going to use the reverse method you will need a dipping can or pot with a sturdy handle, like a metal pitcher. Also, you will have to hang your wicks far enough apart to accommodate the size of the pot. Still, some people find this easier than the traditional dip-the-wick method.

Reverse dipping

Drying Dipped Candles

As dipped candles are usually made in pairs, the wax is still warm when they are finished. Therefore, when hanging dipped candles to cool, make certain they do not touch each other, or they may stick together. You can hang them over two nails or a dowel rod. A coathanger makes a great frame.

You can use hooks or pegs for hanging just-dipped candles to cool. An old-fashioned peg-board—a long board with several pegs inserted—is a good choice for several sets of tapers. You can make such a board easily with screw-in hooks.

Troubleshooting

Dipping candles requires technical mastery. Understanding wax temperatures is crucial, as is how long the wick being dipped stays in the hot wax. Shaping the final candles can be a problem; beware of leaving surface blemishes. Here are some troubleshooting tips:

If during successive dips your candle is not growing, it may be because the wax is too hot. Or, you may be keeping the candles in the wax too long.

If the wax buildup is melting off the candle in the successive dips, the wax is too hot or you are keeping the candles in the wax too long.

If the surface of the candle is forming bumps or blisters, it is because you are keeping the candles in the hot wax too long.

If the candles have lumps and bumps, the wax is too cool.

That’s Wicked

The correct burning of a wick is directly related to the melting point of the wax mixture during the dipping process and the diameter of the finished candle. If your wick doesn’t burn correctly, you can analyze the problem and learn to avoid it in the future. Here are some common wick problems and how to recognize them:

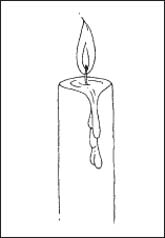

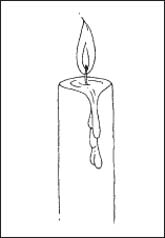

Guttering

You will know when you see a guttering candle that the amount of wax being consumed by the flame is more than the wick can effectively absorb. The melted wax will overflow the candle and drip down its side. This dripping is called guttering.

What causes guttering?

The wick is too small for the wax mixture you are using and the diameter of the candle you have made.

In severe cases of guttering, all of the melted wax will run down the side of the candle, emptying out the pool of liquid fuel. Since the wick will then have no fuel, it will begin to smoke until it burns enough of itself to melt enough candle wax for fuel. At this point, it’s best just to put the candle out, as you will have a drippy mess on the candleholder and whatever is underneath it.

SOLUTION: remelt the candle and try again with a different wick.

Guttering

Cratering

Cratering

This condition occurs in pillar candles when the wick is too small for the type of wax mixture and the diameter of the candle. With cratering, the wick will burn a deep hole in the center of the pillar, creating a “crater” that will fill with the melting wax. As the wick surrounds itself with melted wax, it will extinguish itself in the pool it has made.

SOLUTION: You can take a sharp knife and cut off the top of the candle until the wick is above its surface, then try again to burn it.

Another cause of cratering is when the wick is too large for the candle and absorbs more liquid wax than it can burn for fuel. When this occurs, you will have a smoking wick and a small bead of carbon will form on the tip of the wick.

SOLUTION: You can trim the wick and pour off the excess melted wax. Or, you can simply remelt the candle and use the melted wax to make another candle.

Sputtering

This condition occurs when the candle is not properly made. It may have air or water pockets inside it.

SOLUTION: Depending on the extent of the problem, it is possible that, as the wick seeks its fuel, it will burn past the problem area and be fine. However, if the air/water bubbles are throughout the candle, consider it a total loss and put in the “save for remelting” bag.

Wick Won’t Burn

Occasionally, a wick just won’t let itself be lit, or you light it and it instantly goes out. This problem is usually caused by additives, mostly color pigments of various types, clogging the wick’s wicking system.

SOLUTION: Chances are, this is an unsolvable problem, for if you remelt you’ll still have the clogging additives in the wax mixture. Make a note in your journal to avoid that formula and write it off to experience.

Surface Defects

If you don’t get a smooth surface on your candles (like all the pretty pictures in candlemaking book displays!), it’s because your wax is either too hot or too cool. Wax that is too hot can cause air-filled blisters. Wax that is too cool will thicken and produce a lumpy surface.

SOLUTION: Watch the temperature!

Make It Stick

Adhesion of the layers of wax being built up as you dip is important. If the layers do not meld properly during the successive dips, the candle may separate into concentric circles, like slices of an onion. To achieve good layer adhesion is the aim of the candledipper. Only thus can you produce a candle that is solid wax from core to outer layer. Such a candle won’t come apart unless broken intentionally.

If you are having problems with layer adhesion, there are four things you can try:

Increase the submersion time

Decrease the time between dips

Increase the temperature of the wax

Raise the temperature of your work area and eliminate any drafts, especially cold ones

Use Your Notebook for Troubleshooting

We’ve said it before, and we are saying it again: Keep a notebook—especially when dipping candles. Because submersion time, time between dips, and wax and room temperature are all crucial elements, these should be meticulously recorded in your notebook. Then you can refer to these notes whenever you encounter trouble with dipping candles.

Note any adjustments you make to the temperature of the wax, and record the wax formula used. By doing this, you will know what wax mixture needs which temperature in order to work best. Since each wax mixture will have a different ideal temperature for dipping, notes are invaluable—if any time elapses, you may forget what you did that worked best.

Dipping in Quantity

On occasion you may want to make a large number of pairs of dipped candles—for instance, to decorate the tables at a large party such as a wedding or birthday fete, or to give as gifts during the holiday season. Candles can be dipped in quantity by tying pairs of wicks to a frame, such as has been described above. However, to dip candles in large quantities, you must be certain that your frame is very sturdy. The frame can be a rod, a hoop, or a square. Metal racks such as are used for cooling cookies, or metal broiling pans that are made of parallel rods, can be especially useful to the home candlemaker who wants to do a large production run.

Another way to make dipped candles in quantity is with the coathanger method. Simply use ten hangers (holding two pairs of candles each). Because you have to wait two or three minutes in between dips, you can increase efficiency if you work with several hangers, dipping one after the other.

Helpful Hints for Dipping in Quantity

There are two important points to remember when choosing a frame for making dipped candles in quantity: one, when tying the wicks onto the frame, be careful to leave sufficient space between them to accommodate the finished candles. You will have to decide their thickness in advance in order to do this. About three candle diameters between wicks is suggested for adequate spacing. The second point, and a vital one, is to remember that a frame of many candles is going to be heavy, and will get heavier as you dip and add the layers to make the final candles the thickness you desire.

Dipping for Kids 101

For a children’s project, it’s best to dip a single candle at a time, which avoids the problem of the pair making contact. This also gives the child a long length of wick to hold, thereby avoiding danger of burns or the child’s accidentally getting a hand or fingers into the hot wax.

Keep safety at the top of your priorities. Be sure children are properly protected—an old T-shirt over regular clothes is a good apron. And of course, adult supervision is a must.

What you will need for this is plain paraffin, an empty can for melting the wax and dipping the wicks, a saucepan to use as the bottom half of the double-boiler setup, and wick lengths of 24”, one for each candle to be made.

Fill the saucepan with about 2” of water and heat it over low heat on the stove. Add the paraffin block (or cut it into pieces for faster melting) and let it slowly melt while keeping a close watch. Give each child a prepared wick with the weight already attached to the bottom end. Also provide each child with a small piece of cardboard to hold under the just-dipped candle, to prevent drips on the floor.

When the wax is melted, allow the child (or each child involved in the project) to dip a wick slowly down into the melted wax and then slowly pull it out again. Have the children stand in a line and approach the dipping can of melted wax, under supervision. Have some hooks or a rod available on which to tie the tapers to dry. Allow the children to repeat the dipping process eight or ten times until enough wax has accumulated on the wick to make a nice size candle. The candles will be thinner and smaller than usual, but that’s not important. It’s the experience and the fun of it that count!

When each child has made his or her candle, hang all the candles on the drying rack (with nametags for identification later). When the candles are dry, trim off the extra length of wick used for tying the candles onto the rack, to about ½”. An adult should be in charge of trimming off the candle bottoms. If this is a school project, send the candle home with the child. If this is a home project, allow the child to light the candle—be sure to give appropriate warnings about candle-burning safety.

Be aware that these simple, paraffin-only candles will not burn as long or as well as those made with additives. But pure paraffin is lovely to watch burn as it gives a translucent glow—and what could be lovelier than helping kids to get creative?

Teacher’s Tip

Candlemaking at school by a group of children can become a festive activity during the holiday season. A field trip to a candlemaking facility, the telling of a story about how the candle represents the light of life, the singing of a holiday song—all could be adjuncts to the candlemaking project.

If you make special candles for holidays such as Christmas, it’s especially important to keep careful notes. You may know your everyday procedures by heart, but after a year has passed, you are likely to have forgotten exactly how you made those lovely beeswax candles that everyone so admired!

Candle-Burning Safety

Fire can be a friend—or a foe. The following precautions will ensure that the pleasure of using the candles you’ve made doesn’t become a disastrous experience.

Never leave a burning candle unattended

Always put tapers in candleholders that fit properly

Place candles in a secure area away from drafts or pets

Make sure the candleholder is nonflammable

When lighting candles with kitchen matches, dip the match in water before discarding—many a hot match has ignited paper in a trash basket!

Keep the candlewick trimmed to ½-¼” for better burn

Avoid splattering melted wax when blowing out a candle by cupping your hand around the flame first

Trim candle after extinguishing it, while the wick is still warm—trimming a cold, burnt wick can damage it and make it difficult to relight

Good News about Wax Removal

Throughout this book, we have cautioned you to carefully cover all work and surrounding surfaces to avoid the problem of spilled wax. We’ve suggested you wear old, disposable clothes. Now—as an avid reader of mail-order catalogs—I am able to bring you some good news. I have recently discovered some wax-removal products that actually work!

The Vermont Country Store sells a product called “Wax Away,” which they claim removes spilled candle wax even from delicate linens, works fast with no scraping, and will not stain. An 8-ounce bottle is $8.95. Call (802) 362-0285 or reach them on the Web at www.vermontcountrystore.com.

Called simply “Wax Remover” by its purveyor, this product loosens wax so you can simply lift it off. A liquid, it can be used on wood, plastic, or painted surfaces, carpets, tablecloths, and clothing. An 8-ounce bottle costs $9.95. Contact Illuminations at (800) 226-3537 or visit their Web site at www.illuminations.com.

Candle Care Kit is an excellent collection that contains a silver-plated candle shaver, stainless steel wick trimmer (angled to reach deep-set wicks in pillars), steel tweezers to remove wick debris, Wax Remover, and Candle Stickers. The Candle Care Kit is also available from Illuminations (see their contact information in the preceding paragraph).

Create a Pure Beeswax Dipped Candle

In the Middle Ages, only churches and the royal families had access to beeswax. (Incidentally, the bee has long been a symbol for royalty!) Although it is possible to purchase pure beeswax candles today, they are extremely expensive. Making your own is gratifying—and a lot cheaper! And hand-dipped candles have an appearance that can’t be beat by factory-made ones. They burn beautifully, and no wax is better suited to this method of candlemaking than the beautifully colored and scented wax made by those industrious and useful creatures we call bees.

To produce two pounds of wax, bees have to consume about fourteen times this weight in nectar. The wax is secreted in small flakes from glands on the underside of the bee’s abdomen. The bee strips off secreted wax to use for the construction of the honeycombs. Fresh wax—known as “pure” wax—is white. Its fragrance depends on the bees’ sources of nectar, which could be a single source like clover, or wild flowers, or other types of plants that produce nectar the bees can consume.

Getting Started

To make one pair of pure beeswax candles, you will need these materials:

A 1 ½”-primed wick, about 20” in length (beeswax requires a heavier wick than paraffin mixtures)

A dipping can 2” taller than the length of the candles you plan to make, filled with pure beeswax

A saucepan or Dutch oven deep enough to hold water two thirds of the way up the dipping can

Wax thermometer

Soft cloth for polishing, such as those used to polish silver

Steps to Making Pure Beeswax Dipped Candles

Heat the wax until melted. Hold the measured piece of wick in its center and dip both ends into the wax. Remove. Repeat three times.

Continue dipping the wax-coated ends of the wick into the melted wax until the wax builds up. By hand-dipping you can achieve candles much thicker than those commercially produced, and with a nicer shape.

Beeswax melts at 140–145° Fahrenheit. Use the thermometer to maintain a constant melt; otherwise you may find a skin forming over the wax as you work and the wax cools. Either maintain a low heat under the saucepan, or return the dipping can to the hot water for reheating when necessary.

After about thirty dips, your beeswax candles will be approximately the diameter of standard-sized tapers you buy in shops.

Continue the dipping process, allowing the candles to dry a bit in between dips, until they have reached a diameter of approximately l½” at their base.

Immediately dip the candles into a bucket of cold water, which will give them a beautiful sheen, then hang them up to dry. When they are completely dry, buff the candles with a cloth.

Once formed into a beehive, the white honeycomb wax begins to turn yellow. As the combs age, the color darkens to the familiar honey-color we know. This aging process explains why there are differently hued beeswax sheets and candles.

Beeswax is used not only for candles but also to make artificial fruit and flowers. It’s also a good modeling wax. Further, it is an ingredient in the manufacture of furniture and floor waxes, leather dressings, inks, ointments, cosmetics—even waxed paper!

Overdipping: Another Kind of Dip

Dipped candles by definition (see above) are pairs of candles on which wax has been built to a certain thickness by repeatedly dipping a single wick into the melted wax.

There is, however, another kind of dipping—called “overdipping.” Overdipping, put simply, is submerging a finished candle in a final wax bath either to layer a candle with color or to put a layer of super-hard wax on the candle, with a higher melting point than the wax in the center of the candle, to prevent dripping. This process makes the wax on the outer layer burn more slowly than the wax at the center of the candle. The wax closest to the wick is consumed by the wick’s flame before it can pool and drip over the side of the candle, or, in the case of pillars, make a crater or deep pool of melted wax that will extinguish the wick.

Overdipping in a higher melting point wax creates a hard shell on the candle, which protects its surface. It can also serve to cover up any surface blemishes on finished candles. Or, it can be used to change the color of a tinted candle. You can even make a half-and-half (say, blue and white) effect by overdipping only the bottom half (or other portion) into the colored wax. Quite dramatic color effects can be obtained by overdipping, such as adding strongly contrasting colors over white. As the candle burns, the contrast is revealed. Or, you can overdip a second color over a first color—for example, a red over a pink—for an unusual effect in the burning candle.

Overdipping rolled candles will seal them together and prevent them from coming unrolled (which can happen in hot weather or an overheated room). Simply overdip your rolled candles in clear wax. This process gives a nice, finished look to the rolled candle; it is especially recommended if you have rolled the candle into a spiral shape.

Overdipping is also useful for creating decorated candles. By overdipping the finished candle in plain paraffin, which is translucent and won’t affect color, you can adhere small decorations, such as beads or sequins, to the candle’s surface.

Additionally, candles can be overdipped with the same wax you used to make them if you add 10 percent of the hardening agent microcrystalline.

When overdipping in beeswax, no additives are needed. As an overdip, beeswax is more economical than making a pure beeswax candle—it gives the appearance of pure beeswax, its color, and signature honey fragrance, without using up a lot of beeswax. Plus, overdipping in beeswax will give a longer burn time.

Method for Overdipping Candles

Don’t confuse overdipping with dipping. You can overdip tapers, but you can also overdip almost any kind of candle you make. Pillars especially lend themselves to overdipping and special effects from overdipping. Here’s what you’ll need for overdipping:

A wax or wax mixture with a high melting point (check the temperature with your thermometer)

Stearic acid—5 to 30 percent relative to the wax, depending on the effect you want to achieve (remember that stearic acid makes paraffin opaque)

A container of cool water deep enough to submerge the candle, to add shine to the finished candle and to cool it

Your double-boiler setup

Pliers (needle-nose pliers work well)

Colorant or dye, if you are going to overdip in color (usually over a white candle, but not always: you could overdip a lighter colored candle in a darker color)

Overdip with Clear Wax

Melt the wax about 20° above its melting point. For proper adhesion of the overdip layer, the candle should be still warm, not cold. If you have a cold candle (for example, if you purchased white candles and are going to overdip them in color or beeswax) you must warm the candles a bit before dipping. Small candles and tapers can be held between the hands; larger ones, like pillars, can be put in a warm spot—but not too warm and not for too long, or they will begin to melt!

Holding the candle by its wick, using the pliers (recommended for bought candles or those with already trimmed wicks), or your fingers if the wick is sufficiently long (as it would be with handmade dipped pairs), completely submerge the candle in the clear wax. Pull it (or them, if a pair) out steadily. The overdipping must be done quickly because the wax is hotter than usual and you want to avoid beginning to melt your candle.

The overdipped candle will be quite warm, a bit soft, and slightly pliable for a few minutes. Continue to hold it aloft by its wick until it begins to set. Although some candlemakers consider a single dip sufficient for an overdip, others recommend dipping two or three times, allowing about thirty seconds between dips. This is your choice. Again, experimentation is the answer. And, yes, keep notes!

After the final dip (if you use more than one) plunge the whole candle into a bucket of cool water for a glossy sheen on its surface. Then polish lightly.

Overdip with Colored Wax

If you want to overdip a white candle with color, or a colored candle with another color (or several colors) to achieve different and exciting effects, you will need a container for each color you plan to use. For example, if you wanted to dip a candle half in green and half in red for Christmas use, you would need two containers, plus the candle(s).

Overdipping in colored wax requires a large amount of wax, because you have to either submerge the candle entirely or do it by halves or sections. However, any leftover wax can always be reused another day and another dip.

If your candles are not picking up sufficient color in two or three dips, your wax is too hot. If, on the other hand, the coating of colored wax is blemished, or scaly, the wax is too cool. Solution: Always use your thermometer and keep a close watch on it. And—always take notes.

Follow the instructions above for preparing to dip in clear wax and add the color or colors you want to use to each container. You will need to melt the wax in each container, so either do all of one color at once and then switch to the second, third, etc. colors in sequence; or, if you have the space and the equipment, you can set up more than one double-boiler for melting the wax for overdipping.

There are many interesting, dramatic, curious, fun effects to be made with overdipping. We’ll explore these unusual types of candles in the following chapter.