IN March 1963, Parker worried about the arrival of a different kind of visitor, though there was nothing in her demeanor to indicate that she would become a pivotal figure in anyone’s life, let alone the Colonel’s. Petite, pretty, empty-headed except for the usual teenage obsessions, and positively gooney-eyed with love, sixteen-year-old Priscilla Ann Beaulieu had captured Elvis’s heart in Germany, and now she was moving to Memphis.

The stepdaughter of an American air force captain newly stationed near Friedberg, Priscilla had bragged to a girlfriend back in Texas that she was “going over there to meet Elvis.” She achieved her goal in a week and a half. Lamar Fike remembers that she showed up at the house that first night wearing a blue-and-white sailor suit and white socks. “I said, ‘God Almighty, Elvis, she’s cute as she can be, but she’s fourteen years old. We’ll end up in prison for life.’ I watched that from the very beginning with abject fear.”

Parker had long known about her, both from his spies among the entourage, who reported Elvis’s every move, and from stories in the press. Life magazine had photographed Priscilla at the Rhine-Main air base as she waved Elvis good-bye, captioning their picture “The Girl He Left Behind.” Elvis denied that he was smitten (“Not any special one,” he told reporters when they asked if he’d “left any hearts” in Europe), but an elaboration (“There was a little girl that I was seeing quite often over there . . .”) and a telltale grin said otherwise. It was she he’d spent his last night with in Germany, and he hadn’t stopped thinking about her, instructing her to write to him on pink stationery so her letters would stand out in the avalanche of mail. On several occasions, he’d brought her to the States to visit.

Now, Elvis had persuaded Captain Beaulieu to let Priscilla come to Memphis and attend Immaculate Conception High School, where, he told him, the girls wore uniforms and studied under the tutelage of stern-faced nuns. The implication was that Elvis would marry Priscilla when she was old enough, but “he didn’t give them a time,” she remembered later. “He just said, ‘I want her here.’ ”

The immediate promise was that a chaperoned Priscilla would live on nearby Hermitage Road with Vernon and his new wife, Dee. That arrangement lasted only a matter of weeks, Priscilla slipping back and forth between the houses. With Grandma Minnie Mae Presley serving as lenient watchdog, the teenager soon took up residence at Graceland, sharing Elvis’s bed—though chastely, she maintains—and learning the drug protocol that allowed her to participate in his night-for-day world.

During Presley’s army years, Parker had steadfastly refused to allow Elvis’s most serious girlfriend, Anita Wood, to travel to Germany to see him. (“We had to keep everything so quiet . . . the Colonel said it would hurt his career.”) But though the Colonel took an unusual liking to Priscilla, he was furious at such a Lolita-like setup. Elvis was now twenty-eight years old, with twelve years’ difference in their ages. Not so long before, in a redneck hormone storm, the piano-pounding Jerry Lee Lewis had ruined his career by marrying his underage cousin. This situation wasn’t nearly as dangerous, but if discovered, it would still be a scandal, and Presley’s movie contracts had morals clauses in them—a fact, along with paternity suits, that was never far from Parker’s mind.

If Elvis insisted on living with Priscilla for any length of time, the Colonel saw, they needed to marry, and Parker told him so. A marriage might calm Elvis down, especially in Hollywood, where the starlets lined up to be admitted to his parties.

After first joining Elvis in California, where he was making Fun in Acapulco for Paramount, Priscilla was relegated to Memphis, where she waited impatiently for him to return between pictures. Priscilla was not alone in noticing that his behavior, fueled by a steady stream of uppers, downers, and sleeping pills, was becoming frighteningly erratic. In fact, one night Elvis’s temper was so raw he threw a pool cue at a female party guest who had insulted him, injuring her shoulder and collarbone. He was sorry—he broke down and cried and said he hadn’t known what had come over him, except he felt increasingly boxed in by the lightweight movies he derisively termed “travelogues” for their quasi-exotic locales. He was doing three and, soon, four a year, rubbed thinner with every picture, and suffering nosebleeds on the set from anxiety.

Fun in Acapulco, Elvis’s fifth film since Blue Hawaii, was a perfect example of the kind of empty fare that continued to satisfy his fans, if not the actor himself, and is memorable only for a quavering, if coincidental connection to the life of Andreas van Kuijk. In it, Elvis plays an ex–circus performer, an aerialist, who in a moment of fright and misjudgment, allows his brother to fall to his death. Traumatized, he flees the circus world to escape his past and assume a new life in a foreign country.

The film, which at one point has Elvis’s character, Mike Windgren, sending a telegram to his hometown of Tampa, Florida, was directed by Richard Thorpe (Jailhouse Rock), who again explores the theme of a young man jeopardizing his future through the tragedy of accidental death. As in his earlier film, Thorpe includes the character of a talent manager—a pint-sized Mexican shoe-shine boy (“Are you sure you’re not a forty-year-old midget?” Elvis asks)—who takes 50 percent of his - client’s money, insisting he’s not an agent, but a partner. Since Elvis was unable to travel to Mexico, the studio relied on a variety of process shots, mostly background projection, to place him south of the border.

By now, in keeping with the Colonel’s cross-promotional synergy, RCA culled most of Elvis’s singles from the largely dreadful soundtracks. Since 1961, he’d enjoyed a chart-topper with “Good Luck Charm,” and watched a pair of hits, “Can’t Help Falling in Love” and “Return to Sender,” climb to number two. Yet no Elvis release was a sure bet anymore—some singles failed to crawl out of the thirties—and Parker put the pressure on Bill Bullock in RCA’s New York office to make things happen. “I may not type good,” Parker joked, a comment on his two-fingered keyboard style, “but they sure do know what I mean up there.”

Indeed, they did. A memo went around at RCA with the instructions “always remain friendly with the Colonel,” a directive that struck fear in the hearts of those who remembered how he’d gotten one executive fired over an altercation regarding Brother Dave Gardner, whom Parker had brought to the label. Now, if Presley wanted his records mixed one way—with his voice as part of the instrumentation—and Parker wanted Elvis more out front, it was Parker the label obeyed.

In early ’62, he worked out a new arrangement with RCA concerning previously released material. The agreement provided both Elvis and the Colonel with substantial new revenue from special side deals, which Parker would later refer to as joint ventures. They would split those monies 50–50.

The contract, which Parker insisted be no longer than one page and contain no legalese, would be renegotiated seven months later. It was changed so often, said one employee, that “RCA has nothing to say about anything Elvis does or anything we do for him.” Though the label’s lawyers insisted the company back out of promoting a forty-three-city tour in late ’62—an artistic disappointment for Elvis and a financial loss of more than $1 million—Parker was regarded as the absolute power.

Consequently, the staff went into a frenzy if he happened to drop by unannounced. Joan Deary, Sholes’s secretary, worked out a signal with someone downstairs so she could get the office in order before she met him at the elevator, when Parker would “just explode out into the hall.” The first time it happened, she rushed to put out an autographed picture the Colonel had sent her boss for Christmas. “None of us liked it,” she remembered, “and we’d put it in a drawer behind the door to Steve’s office. I went flying in there to pull it out, and I banged into Steve, who was also trying to get the picture out of the cabinet and on display.” Bill Bullock was only half kidding when he sent Parker a large office clock inscribed, “Colonel, it’s whatever time you want it to be.”

Unlike the men at RCA, ever-present for Parker like dutiful sheep, publicist Anne Fulchino was the only one to contest the Colonel. Concerned about Elvis’s morale and the erratic chart placement of his records, she asked Tom Diskin to take her to see Presley on the Paramount lot one day in early ’63. “That kid was not only unhappy, he was ashamed for me to see him prostituting himself with those crummy pictures,” she remembers. She sat down with him and explained her campaign for promoting his records, “practically drawing him a diagram on how you build a star.”

Elvis realized he needed to make major changes in the direction of his music and his movies, and promised Fulchino he would do so. But though she believed Elvis “knew Parker was not the right manager for him—the way the Colonel wanted him to go was not the way Elvis wanted to go”—he allowed himself to be hamstrung with unsuitable projects.

On the set of Kissin’ Cousins, filmed only months after his talk with Fulchino, Elvis told costar Yvonne Craig that he figured the Colonel would know when the time was right to return him to dramatic pictures. Was Elvis merely saving face? The Colonel’s dominance was so strong that Presley may have thought he was incapable of standing up to him, even to demand stronger scripts after Parker turned down his one request to approve them. (“If they’re smart enough to pay you all that money, they’re smart enough to write a good script.”) But Elvis’s reticence—his lack of emotional backbone—proved to be his fatal flaw.

Adam van Kuijk with three of his children, from left Ad, Jan, and Johanna, about 1922. He would die three years later, at the age of fifty-nine. (Courtesy of Maria Dons-Maas)

The van Kuijk family lived in the stable of the van Gend & Loos building, seen here to the right of the music hall, marked “Kon. Erk. Harmonie De Unie.” (The collection of Dirk Vellenga)

Anna van den Enden was murdered in the living quarters behind this shop at Nieuwe Boschstraat 31, in May 1929. (Tony Wulffraat)

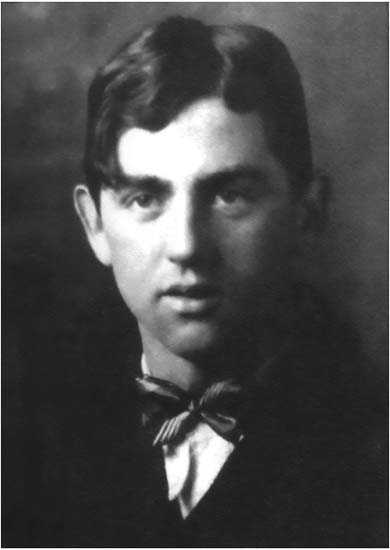

Andreas van Kuijk, aka Tom Parker, circa 1926–7, likely during his Chautauqua days on his first trip to America. (Elvis Presley Enterprises. Used by permission)

The well-dressed young gentleman, age nineteen, in the year he disappeared from his native Holland. (The collection of Dirk Vellenga)

Private Thomas Parker (seventh from left, middle row) in the 64th Coast Artillery Brigade Regiment, stationed at Fort Shafter near Honolulu, probably fall 1929. Fellow soldier Earl Kilgus stands behind him, back row, fifth from left. (Courtesy of Earl Kilgus and Robert H. Egolf III)

Cees Frijters received this picture of Andre as an American soldier, stationed at Fort Shafter. (The collection of Dirk Vellenga)

A photo Andre sent home to his family, probably in 1932, when he was stationed at Fort Barrancas, near Pensacola, Florida, in the 13th Coast Artillery. (The author’s collection/source unknown)

Private Thomas Parker’s army discharge record, which identified him as a psychopath. (The author’s collection)

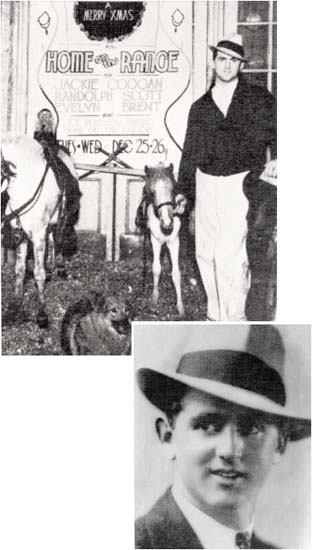

Not long out of Walter Reed Army Hospital, working a movie event, most likely in Tampa, 1935. (The author’s collection/source unknown)

Late 1930s: Looking every inch the carnival press agent, though front offices jobs would always be denied him. (The author’s collection/source unknown)

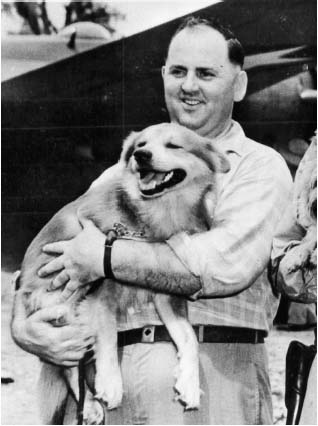

Parker, as a Humane Society field agent, during filming of Air Force at Tampa’s Drew Field, 1942. (Tampa Tribune)

When Hollywood came to Tampa in 1943 for A Guy Named Joe, Parker (back row, with ice cream) invited the camera crew on a picnic at a friend’s house. Bobby Ross sits at Parker’s right with his girlfriend and future wife, Marian DeDyne. Marie appears front row left. (Courtesy Sandra Polk Ross and Robert Kenneth Ross)

By 1944, Parker had signed on as the booker and advance man, or “general agent,” for the Jamup and Honey tent show, where he met Gabe Tucker (right). (Courtesy of Gabe Tucker)

As the new manager of country singer Eddy Arnold (left of poster), Parker (far left) staged a 1946 promotion in Tampa to bring out the crowds. (The Country Music Foundation)

RCA’s Steve Sholes (middle), with hopeful recording artist Dolph Hewitt (left), joins Parker and Eddy Arnold at an industry convention, probably 1949. (The collection of R. A. Andreas and “. . . .and more bears.”)

Parker, desperate for a title and not yet a “Colonel,” signed this mid-forties portrait to Bobby and Marian Ross as “The Gov.” (Courtesy Sandra Polk Ross and Robert Kenneth Ross)

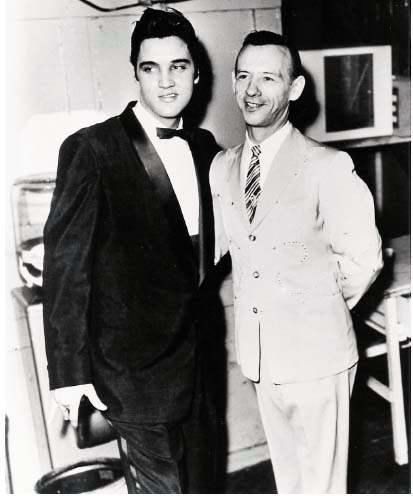

Country singer Hank Snow beams beside Elvis Presley, backstage at the Grand Old Opry, December 1957. Parker had cut him out of half of Presley’s management the year before. (The author’s collection/source unknown)

The Colonel helps Marie celebrate granddaughter Sharon Ross’s first birthday, May 2, 1951. (Courtesy Sandra Polk Ross and Robert Kenneth Ross)

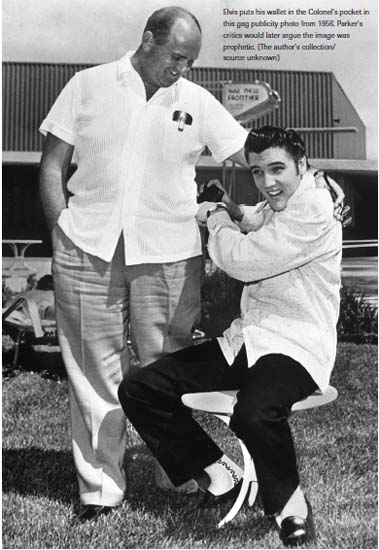

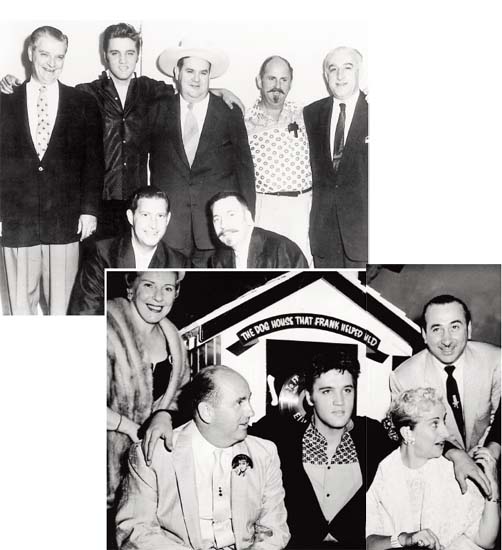

Elvis joins Parker, sporting fake goatee (back row), with RCA brass Bill Bullock (back row, far left), Steve Sholes (back row, center), and Hill and Range liaison Freddy Bienstock (front row, left), circa 1956. (The collection of Robin Rosaaen)

As a birthday present for Steve Sholes, Colonel Parker had an elaborate dog house built in honor of Nipper, the RCA mascot. Elvis poses in front of it with the Colonel and Marie (right) at Sholes’s party at the Beverly Hills Hotel, 1957. The “Frank” mentioned in the legend over the door (“The Dog House That Frank Helped Build”) is Y. Frank Freeman, the famed Paramount Pictures executive, and alludes to Elvis’s films helping sell records. (The collection of Robin Rosaaen)

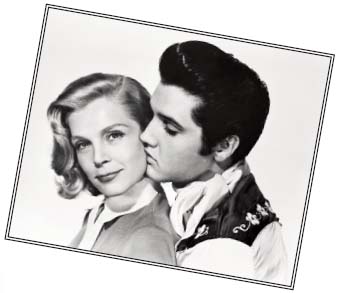

Loving You, released in 1957, costarred Lizabeth Scott as Glenda Markle, a manipulative press agent and manager who reprised a number of Colonel Parker’s real-life publicity stunts. (Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences)

The Colonel and Elvis make merry in a red BMW Isetta “bubble car,” Presley’s Christmas gift to his manager, December 1957. (Nashville Public Library, The Nashville Room)

When Texas Senator Lyndon Baines Johnson invited Eddy Arnold to entertain Mexico President Adolfo Lopez Mateos at the LBJ ranch in October 1959, Parker went along, and parlayed a meeting into a friendship. Johnson’s daughter, Lynda Bird, watches at right. (Oliver Atkins / George Mason University.)

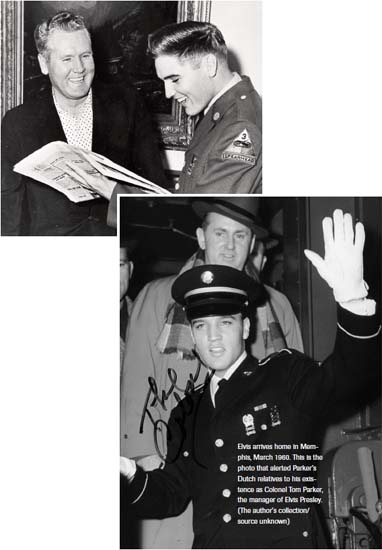

Vernon Presley, the Colonel’s ally, accompanied Elvis to Germany in 1958, and conducted business with Parker in the U.S. by letter. Here, Vernon enjoys a press item with his son. (Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences)

Parker, dressed in his favorite get-up, a Confederate uniform, dances with Marie at a party on the set of G.I. Blues, 1960. (The collection of the Bitsy Mott Family)

Parker loved getting the best of Hal Wallis, seen here in the Colonel’s Paramount office in 1960, modeling a paper hat stamped “G.I. Blues.” (Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences)

Elvis chuckles at a get well letter the Colonel wrote to Harry Brand, head of publicity for Twentieth Century Fox, during the making of Flaming Star, 1960. From left: Bitsy Mott, Tom Diskin, producer David Weisbart, Parker, Elvis, director Don Siegel, and music/sound effects editor Ted Cain. (The collection of the Bitsy Mott family)

“We do it this way, we make money; we do it your way, we don’t make money,” Parker seems to be telling his client in this undated photograph, probably from the early 1960s. (The collection of the Bitsy Mott family)

A cozy pose with Hal Wallis, probably during the making of Blue Hawaii, 1961. (Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences)

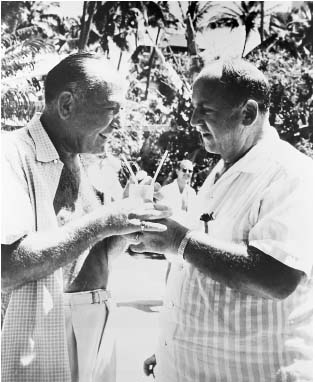

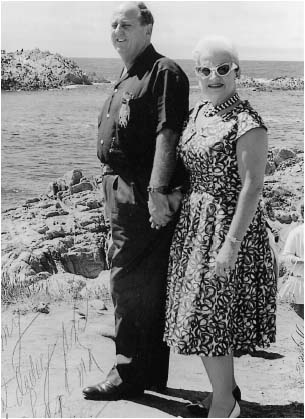

Parker with “Miz Ree,” as he jokingly called his wife, on Waikiki, 1961. The picture is inscribed to Bobby Ross’s family. (Courtesy of Sandra Polk Ross and Robert Kenneth Ross)

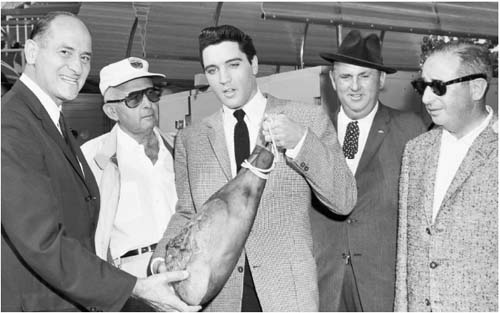

The Colonel valued few gifts as highly as a ham. Here, on behalf of Tennessee governor Buford Ellington, he has Elvis present one of Tennessee’s finest to Washington State’s first Italian American governor, Albert Rosellini. Elvis was in Seattle filming It Happened at the World’s Fair in September 1962. From left: Rosellini, director Norman Taurog, Elvis, Parker, and producer Ted Richman. (Museum of History and Industry, Seattle)

A 1960s portrait, signed to Gabe and Sunshine Tucker. (The author’s collection/source unknown)

Billy Smith sits on the Colonel’s knee during the making of Frankie and Johnny, 1965. (The collection of Maria Columbus)

The Colonel’s joke button, probably from the 1960s. (Courtesy of Gabe Tucker)

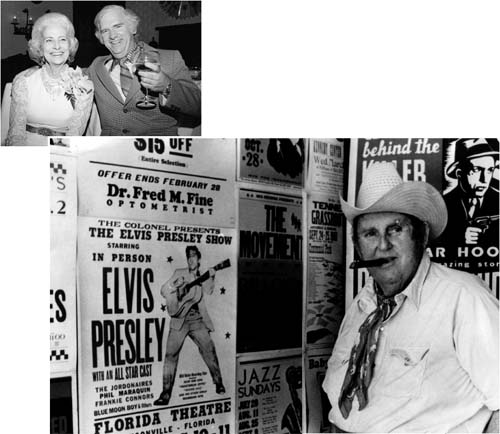

Tom Diskin, with Marie, raises a glass at a party to celebrate the Parkers’ wedding anniversary, probably in the 1970s. (Courtesy Sandra Polk Ross and Robert Kenneth Ross)

The Colonel at Hatch Show Print, Nashville, in 1987, with a reproduction of one of his early Elvis concert posters. (Nashville Public Library, The Nashville Room)

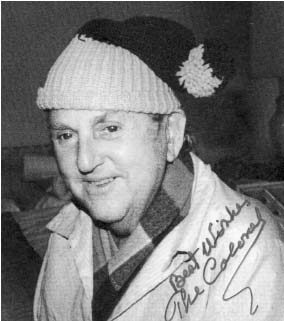

Described as “a combination of con man and Santa Claus” by the New York Times, Parker resembles the latter in this undated portrait in a knit cap. (The author’s collection/source unknown)

With the author, first meeting, Las Vegas, 1992. (Judy F. May)

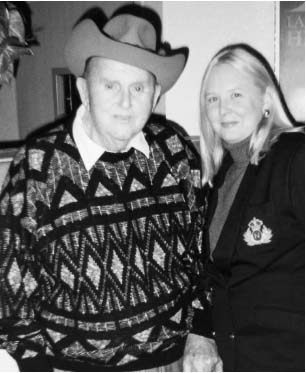

The Colonel and Loanne, 1994. (Alanna Nash)

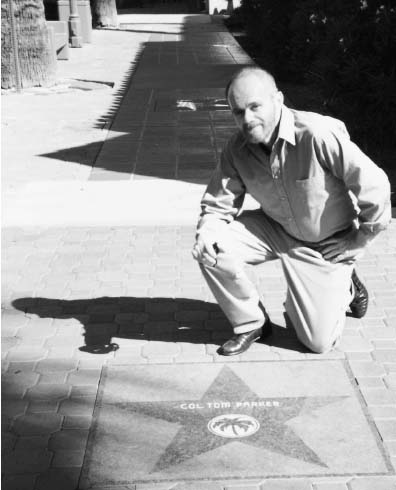

Byron Raphael at Parker’s plaque in the Walk of Stars, Palm Springs, Calif., 1998. (Alanna Nash)

Fed by his father—who was beginning to question the Colonel’s choices, though still bowing to financial concerns, keeping the books and fretting over every penny—Elvis’s constraint found its genesis in the mother-son teachings of Gladys. After her husband went to prison in 1938, it was she who taught her young son to fear authority so that he might survive in a hostile world, never dreaming that he would rise above his social class, where such behavior would become inappropriate.

Elvis made fun of the Colonel to the guys, yet he remained subservient to his face. His refusal to challenge the Colonel factored into the stunting of his personal growth and development, as well as his self-loathing and escalating drug dependency. He turned his anger inward and numbed it with pills.

A turning point came in 1963 with the filming of Viva Las Vegas, Elvis’s best MGM picture in the post-army years. With the casting of Ann-Margret, the first costar to generate real electricity with Presley on screen, Parker should have seen that Viva Las Vegas plugged two live wires together, made a formula musical sizzle, and ensured that future films reconnected such high voltage.

But Parker was threatened by an actress who both competed with his star and engaged Elvis’s attention offscreen, as Ann-Margret did from the start. And it’s true, as the Colonel complained, that it was difficult to distinguish just whose film it was. Instead of playing up their natural chemistry, he grumbled that Ann-Margret got more close-ups and flattering camera angles, and fought to cut their duets to just one song. Finally, he vetoed special billing for her in the advertisements that MGM hoped would help draw audiences beyond the usual Presley fans. “If someone else should ride on our back,” Parker told the studio, “then we should get a better saddle.”

Parker was likewise clueless as to how the movie rejuvenated his - client’s spirits and musical dynamism, particularly with the jumpy title tune. During filming, the Colonel brought his friend Gene Austin to the set and had Elvis rehearse the tunes to the old crooner for comments.

“He was singing one song,” recalls Austin’s wife, LouCeil, “and the Colonel said, ‘Now, Elvis, I don’t like about eight bars of that. Call David Houston [Austin’s godson, then a hopeful country singer] and sing it to him, and then tell him to give you the Gene Austin licks for those bars.’ ” Elvis was angry and embarrassed, but kept it to himself, concentrating instead on his banter with Mrs. Austin. “When you’d pay him a compliment,” she remembers, “he’d always say, ‘Thank you, ma’am, honey.’ ”

After a string of disappointing flicks, Viva Las Vegas, directed by George Sidney (Annie Get Your Gun), would topple Blue Hawaii as Elvis’s highest-grossing film ever—by 1969, revenues would reach $5.5 million, up from Elvis’s usual picture gross of $3 million. Its success should have shown Parker that spending money for more alluring costars, creative directors, and imaginative scripts would go a long way to assure his client of longevity. However, at the time, all he saw was that Viva Las Vegas had soared over budget.

At MGM, Parker preferred working with men like Sam “King of the Quickies” Katzman and Joe Pasternak, who guaranteed tight shooting schedules and production costs, and welcomed the fact that the Colonel rarely requested story conferences. Katzman nonetheless asked the Colonel to read the screenplay for Kissin’ Cousins, but Parker told him it would cost him $10,000 and then diffused such an outrageous demand with a vote of confidence similar to what he’d told Elvis: “If you didn’t know what you were doing, you wouldn’t be here.” Kissin’ Cousins was an embarrassment to Elvis, however, and Katzman would go on to make the worst picture of Elvis’s career, Harum Scarum.

When Joe Pasternak made the first of his two Elvis pictures (Girl Happy and Spinout), both shot in thirty-two days, the producer took the Colonel aside and said, “Look, you can’t make a picture where the star takes seventy or eighty percent of the cost.” Parker was resolute. “He said, ‘I’m sending you Elvis Presley.’ He didn’t want to boost the price up, but he wouldn’t budge on Elvis, and he’d want to save on everything else.”

Elvis resented the financial shortcuts on his films, as well as the shoddy technical workmanship on Kissin’ Cousins that prominently showed his stand-in, Lance LeGault, in the finale march. (“Sam Katzman said, ‘It’s too expensive to shoot it over—no one will even notice,’ ” remembers Yvonne Craig.) But he was particularly crushed to read an interview with Wallis in the Las Vegas Desert News and Telegram in which the producer said it was the profits from the commercially successful Presley pictures that made classy vehicles like Peter O’Toole’s Becket possible. “That doesn’t mean a Presley picture can’t have quality, too,” Wallis added, but the damage was done.

Still, while Presley usually managed to remain calm and professional on the movie sets, his frustration sometimes poured out in the soundtrack sessions at Radio Recorders, where he could barely hide his discomfort at recording bland and pathetic pop songs like “(There’s) No Room to Rhumba in a Sports Car,” “Do the Clam,” and “Petunia, the Gardener’s Daughter,” provided by the Hill and Range writers. One day, anguished at a song put before him, Elvis made a crack about somebody in the business. Everyone laughed, but he quickly recanted. “I didn’t mean that, guys,” he said. “The Colonel told me to always say nice things.”

Freddy Bienstock understood the predicament but was powerless to change it. “Once we started on the MGM contract, with four pictures a year, it was like a factory,” he says. “Each producer would send me ten or eleven drafts of the script, and I would mark those scenes where a song could be done without being absolutely ridiculous, and then I would give those scripts to seven or eight songwriting teams. I’d wind up with four or five songs for each spot, and then I would take them to Elvis and he would choose which one to do. But there was no way to have better music, because from the moment one picture was finished, we would have to get started on the next one.”

Presley was especially embarrassed to be locked up in Hollywood doing mediocre films while the Beatles—who would visit him at his Perugia Way home in Hollywood in August of ’65—threatened his supremacy in musical history, even as his Roustabout soundtrack would best their latest album on the charts. But an argument can be made that whatever - Parker’s intent, Hollywood helped keep Elvis a big star and in the money during a period when his record career might have languished, especially in the protest-and-psychedelic era.

The popular consensus that Parker denied Elvis a significant place in ’60s music history comes under fire from several music journalists, including Michael Streissguth, who doubts that Elvis—working strictly in music—would have escaped the fate of other ’50s stars. RCA was slow to respond to ’60s rock and roll, and since Elvis wrote none of his own material, the label would have had difficulty knowing what do to with Presley during those rapidly changing times.

“By dumb luck,” says Streissguth, “the movie years had the effect of preserving Elvis economically while the wild music environment passed over. Elvis was not spent from years of musical rejection, so when the time was right and people were ready to see him in concert, he was fresh and ready to pounce on the opportunity. Inadvertently, Parker’s decisions in the early and mid-’60s gave us the great Elvis music of the very late ’60s and early ’70s.”

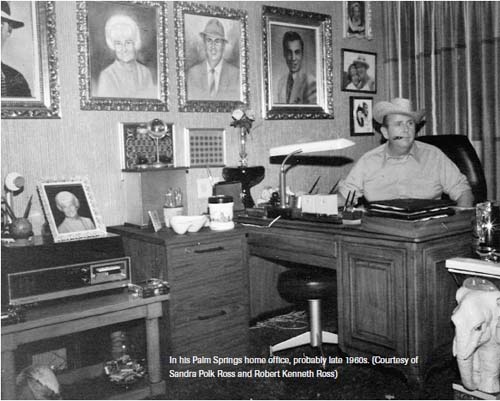

Starting around 1963, the Colonel, whose physical meetings with Elvis had always been sporadic, became even more remote, spending much of his time in Palm Springs, the hangout for Frank Sinatra and the good ol’ boys of Hollywood. For several years, he’d commuted on the weekends, filling the car with weighty bottles of Mountain Valley Spring water and schlepping Marie’s favorite houseplants from Los Angeles, staying first at the Spa Hotel, where he enjoyed the baths, and then at a house at 888 Regal Drive, compliments of the William Morris Agency. Then one day in the mid-’60s, he fell over in the driveway with another heart attack—his third—which left him using a cane. Once he grew stronger, he employed it as a prop.

Byron Raphael ran into him at the Tick Tock restaurant in Los Angeles not long after, and he could tell that something awful had happened. “He’d really changed. He had that cane, and he was bent over. It shocked me, because he was like an old man.”

To most people, Parker explained he just had a bad back, and pointed to an exercise contraption and the elastic brace he wore around his waist and upper torso for proof. But he was convinced he couldn’t survive yet another coronary, casually telling associates, “You don’t see any hearses with luggage racks on them,” and made the decision to spend the rest of his life as if there were no tomorrow.

Only the biggest and the most would do. First, he wanted a new house in Palm Springs. He went to work on Abe Lastfogel’s wife, Frances, paying her a visit while she was in the hospital, hauling in a big vase of flowers and sweet-talking her into letting him have the larger, $250,000 one-floor plan house at 1166 Vista Vespero. There Marie would make everything in the house blue and white, right down to the drapes and bedsheets and even gravel in the driveway. And the Colonel coud relax by the pool and get RCA to install a commercial freezer for the vast amounts of meat he bought and inventoried like gold, even as he struggled to keep his weight in check. Parker didn’t mind being fat—as far as he was concerned, his size suited him and added to his psychological heft. But his doctor dictated otherwise.

Sometimes Parker showed up at Elvis’s recording sessions and tried to lift his client’s mood. On occasion, he ordered lunch in for everyone, and routinely traded jokes with bassist Bob Moore, who had known the Colonel since the Eddy Arnold years and considered Parker “a great, great man,” and with Buddy Harman, who drummed on at least nine of the soundtracks and likewise found him to be “a pretty nice old codger, really.” It was a sentiment Parker went out of his way to foster with the Nashville musicians, if not necessarily with the L.A. players. Moore, who’d been on nearly all the movie recordings, remembers the time he walked into the control room where Hal Wallis was sitting in the producer’s chair. “Boy,” the Colonel said to Wallis, “get up and go get me some coffee. Let Bob sit here.”

At other times, it was Elvis he humiliated in front of the movie execs. After Wallis sent Parker a letter complaining that Elvis looked “soft, fat, and jowly around the face” in Viva Las Vegas, asking the Colonel to have a talk with him about his weight, Parker grilled Marty Lacker about his - boss’s eating habits at a recording session. “He’s just been eating what he always eats,” Lacker said, at which point Parker banged his cane on the floor and then raised it in the air, yelling, “Don’t lie to me! Tell me!”

But it wasn’t so much Presley’s eating habits that altered his looks as it was his pharmaceutical habit, according to Lacker, one of the entourage members who alternately carried Presley’s black makeup kit, which the singer filled with pills. Often, they dictated his moods.

At the next session, it was Elvis who couldn’t contain his rage. “He had this big orchestra in there,” remembers Lacker, “and he started singing. He didn’t settle for the first take. They were getting ready to do it again, and Elvis reached his breaking point. He started ranting, ‘I’m tired of all these fucking songs, and I’m tired of these damn movies! I get in a fight with somebody in one scene, and in the next one I’m kissing the dog. What difference does it make how many times we do this song? I’ll tell you what. You just cut the tracks for this next movie, and I’ll come in later and put my voice on.’ ”

Shortly after, the Colonel invited Elvis to join him and Marie and the Tuckers for dinner, but Presley declined, much to Parker’s embarrassment. “Colonel just damned near begged him, and he wouldn’t do it,” Tucker remembers. For years, the Colonel had boasted of never mixing business and pleasure with his client, not even the simple sharing of a meal. (“You do your thing and I’ll do my thing, and it’ll be beautiful,” he had said.) Elvis was in no mood to start now.

With the movie and record deals in place, Parker found himself with plenty of time for something he now considered doubly important: having fun. When he got a call from a promoter about possibly taking Presley out on tour, he’d tell him Elvis was tied up for the next three and a half years, but he’d be happy to rent the gold lamé suit for the weekend for $5,000. Or maybe they’d be interested in Elvis’s cars. He had a tour of those going out soon, and he wasn’t even kidding about that one.

Parker spent much of the day in his fun-house offices at Paramount and MGM cutting up with the cost-free additions to his staff—Jim O’Brien, his private secretary, on loan from Hill and Range; Irv Schecter and John Hartmann, supplied by the William Morris office; and Grelun Landon, courtesy of RCA. Soon, Gabe Tucker would also be there on the Morris dime.

On occasion, Parker referred to O’Brien as Sergeant. But as usual, nobody had any real rank except Diskin, whose desk, a third the size of - Parker’s, was in the Colonel’s private office at MGM. The rest were privates who helped Parker carry out his schemes.

Each morning, the staff arrived at the mazelike Elvis Exploitations offices at MGM and prepared a list of VIP birthdays so the Colonel could make his congratulatory calls, the aides lining up in front of a microphone in the office and singing to whomever their boss had on the phone. “I thought it was kind of rank,” remembers John Hartmann, who went on to manage David Crosby and Graham Nash, Canned Heat, and the group America, “but I did it anyway.”

“We didn’t hurt ourselves workin’,” says Tucker, whose MGM office was in Clark Gable’s old dressing room, and whose duties included tamping down the Colonel’s pipe, which replaced the cigars when Parker got upset. Tucker also ran the “cookhouse,” a so-called carnival kitchen Parker made by throwing an oilcloth over the conference room table, adding ketchup bottles and kitchen chairs, and promoting a stove and refrigerator from the studio so Parker could cook slumgullion, a boiled stew that hearkened to his hobo days.

Most of the time they ordered food in. But after Easy Come, Easy Go, the Colonel would appropriate actor Bob Isenberg from the cast to wear a chef’s hat and serve occasional lunch guests like Abe Lastfogel, who choked down the slices of ham the Colonel piled on to watch the little Jewish man squirm. When that grew tiresome, Parker totaled up the free meals he’d gotten in the last month, instructing Tucker to pick a name from the directory of MGM executives and call to say, “The Colonel thinks you ought to invite us to supper.”

Soon, the requests grew more elaborate and grand. The president of RCA sent him a check for $1 million without any paperwork when Parker asked for a loan for Vernon Presley, allegedly to buy a Memphis skating rink. The Colonel liked his tests.

He began spending weeks at a time in Palm Springs, where Milton Prell had a house (they both also kept an apartment at the Wilshire Comstock in L.A.), and where he could keep a closer eye on his neighbor, Hal Wallis. The producer continued to humor him, sending him, while on a trip to England, a small dish from the Elephant Club for Parker’s collection. Parker wrote him a letter, thanking him for swiping it. “I could tell you that I bought it, but I know that you would have a lot more respect for me if you felt that I had lifted it,” Wallis replied.

Their relationship remained cordial but strained, although Wallis succeeded in getting the Colonel to read perhaps his first script, for the carnival-themed Roustabout, which Wallis produced in part to honor - Parker’s colorful past. (“Of course, we want you to be associated with the project, as I know how close this type of life is to you,” he wrote.) Afterward, Parker sent Wallis an affectionate letter in which he complimented the producer’s ability to make a picture jell. “You have a certain magic wand that makes these things come out even, even if other people - don’t understand it all the time,” he said. “This I respect more than I can put in words.”

Parker may have meant the flattery as a kind of balm. “When I was doing Roustabout,” recalls the screenwriter Allan Weiss, “I went down to Palm Springs and spent a weekend with the Colonel, interviewing him specifically on his circus background. When I got back, Hal Wallis said, ‘How did it go?’ I told him it went fairly well, and I thought we had a good subject for Elvis. Then he said, ‘It was an expensive weekend.’ I thought, ‘Oh, my God, is he referring to the hotel I stayed at, or what?’ I learned later that the Colonel had billed him for his time.”

Wallis took such things in stride, but the two could also go for days and not speak. Afterward, in Palm Springs, it would be as if the incident had never happened, Parker going to dinner and tossing his hat on one of Wallis’s priceless Rodin sculptures just to rankle his host, or asking the producer to play golf with Marie’s grandson, Tommy, when the boy and his sister, Sharon, came for the summer. Later, the Colonel would throw a black-tie party and invite Wallis, among others, answering the door wearing nothing but Bermuda shorts.

Underneath his various guises, however, the Colonel wrestled with increasingly dark moods of depression. Aside from his concern about his heart and his growing estrangement from Elvis, he was deeply worried about Marie.

In the past, there were times when he’d avoided going to Palm Springs because he didn’t want to have to put up with her carrying on about her cats—a dog lover, his ardor barely extended to felines, and he was jealous of her doting on a particular male cat named Midnight.

“I was at the house one day,” remembers Lamar Fike, “and Colonel and I were sitting in the den, talking. Marie came in all distraught and said, ‘Midnight’s on the roof! Midnight’s on the roof!’ Colonel said, ‘He’ll come down.’

“She came back in a little while and said, ‘Midnight’s still on the roof! Do something!’ So Colonel went out with a hose about as big as a - fireman’s, with tremendous pressure, and aimed it at that cat, and blew it over the garage and the porte cochere, and out into the street. It landed on its feet, but boy, was it surprised! Colonel came back in and said, ‘Now, that’s how you get a cat off a roof.’ ”

Lately, though, he’d demonstrated more compassion. Marie’s health had begun to deteriorate. She complained to Gabe Tucker and to her brother, Bitsy, that living with the Colonel was constant stress, and sometimes he got on her nerves so badly she suffered debilitating headaches that left her unable to think straight. But the Colonel believed it was more than that; her mind seemed to be slipping, and sometimes her rantings, he said in off-the-cuff remarks, drove him crazy. Since she was also becoming severely arthritic, after the Tuckers moved out Parker hated to leave her alone, so first he had RCA sales manager Jack Burgess stay up all night with her and play cards. When Burgess grew weary, it was Irv Schecter, one of Marie’s favorites, who got the call. Schecter was probably only too glad to be out of Parker’s office, where the Colonel thought his William Morris recruit had developed ulcers.

It was during the 1964 making of Roustabout that Elvis met Larry Geller, who would become one of the most significant members of the Memphis Mafia and perhaps Presley’s purest friend.

A hairdresser in Jay Sebring’s tony salon, Geller first showed up at Presley’s home on Perugia Way in April ’64 at the invitation of entourage member Alan Fortas. Elvis had heard good things about his work, Fortas told him. Affable and expressive, Geller talked at length to Elvis about his dedication to spiritual studies and the metaphysical, which seemed to set the singer’s curiosity on fire.

“What you’re talking about,” Elvis said, hungry for discussion, “is what I secretly think about all the time. You don’t know what this means to me.” They talked of Elvis’s purpose in life, and the singer confessed he felt “chosen” but didn’t know why. “I’ve always felt this unseen hand guiding my life ever since I was a little boy,” he said. “Why was I plucked out of all of the millions of millions of lives to be Elvis?”

The next day, at Elvis’s request, Geller showed up at Paramount with a copy of The Impersonal Life, a book he thought would aid Presley in his quest. From then on, Elvis would read such books every day, dedicating himself to the study of Eastern religion and the spiritual path, with Larry as his personal teacher. Almost immediately, the entourage, as well as Parker and Priscilla, viewed Geller with suspicion, seeing him as a disruptive interloper who threatened the status quo.

Toward the end of 1964, however, Parker had much bigger things on his mind than bickering among the Elvis camp. That December, he signed a contract with United Artists for two pictures (Frankie and Johnny and Clambake) at $650,000 each. But more important, with the help of Abe Lastfogel, who said it couldn’t be done, he succeeded in completing a deal with MGM for the benchmark figure of $1 million.

Lastfogel thought Parker was crazy, bringing Gabe Tucker in for some light banter to distract the studio lawyers, and insisting he wouldn’t do the deal unless MGM threw in the ashtray that lay on the conference room table. But in the end, he nailed down a deal for three pictures, the first commanding $1 million—$250,000 of which would be paid in $1,000 weekly installments over five years—and the next two drawing $750,000 each. Profit participation was set at 40 percent.

The Colonel couldn’t contain his glee. He’d finally gotten the best of them all—Wallis, Hazen, Lastfogel, everyone. By sheer gall and snow-manship, Parker had succeeded in making Elvis the highest-paid actor in Hollywood, and his career total was even more impressive: since the beginning of their relationship, he’d brokered deals that had earned Presley $35 million. But to the Colonel’s great disappointment, Elvis didn’t seem particularly pleased about the new contract. In fact, since the May departure of Joe Esposito, the foreman of the entourage and the Colonel’s chief spy, Parker couldn’t even get his client on the phone.

Elvis had picked this time to show a rare spurt of independence. In early October, when he reported to Allied Artists to begin preproduction on Tickle Me, he told the Colonel and everyone on the set that it was important to him to be home in Memphis for Thanksgiving. As filming wore on and delays ensued, Elvis realized that the schedule would be tight, but still he kept quiet. Finally, he got his release on Tuesday, November 24, two days before Thanksgiving, with a caravan of cars and a Dodge mobile home yet to transport cross-country.

In late February, Presley went to Nashville to record the soundtrack for Harum Scarum, the first of the three MGM pictures, a Sam Katzman quickie with a plot that called for Elvis to wear a turban, be kidnapped by a gang of assassins, and perform with a Middle Eastern dancing troupe—a scenario that seemed to combine Rudolph Valentino’s The Sheik with the Hawaiian and gypsy stories Parker had suggested to Hal Wallis years before. The session, Presley’s first time in a recording studio in eight months, went poorly as the former rocker balked at singing such lyrics as “Come hear my desert serenade.” Parker, who had kept tabs on Elvis’s mounting dissatisfaction, began sending letters to Marty Lacker, the new Memphis Mafia foreman, stressing the importance of the “caravan superintendent,” as he called him, getting Elvis and company to the coast on time to begin filming.

Elvis, however, was in no hurry to report to California, preferring to spend time with Larry Geller in meditation and study. Weeks went by, and Parker’s continuous calls went unheeded. “Elvis is not ready to come back,” Marty reported, and it did no good for Parker to scream. He was beside himself with anxiety, the studio telephoning night and day and talking breach of contract. To duck their calls, he finally staged an elaborate ruse, having Marie phone Harry Jenkins, who in late 1963 replaced Bill Bullock at RCA in New York.

“My husband is deathly ill,” Marie whispered into the phone. “It’s a bad situation.” She’d just ordered a hospital bed for him, in fact, and she needed Jenkins to get the word to MGM and to Gabe Tucker, relaxing in Houston after months out on the road touring Elvis’s cars. Jenkins dutifully reported the grave news: “Gabe, Colonel is bad sick. Marie wants you to come out and take care of him.” Tucker, afraid that Parker had suffered another heart attack, caught the first plane, only to find the Colonel himself waiting to pick him up.

“Goddamn, Colonel, you scared the hell out of me. Mr. Jenkins said you was in bad shape.”

“Well, I didn’t feel good yesterday.”

They went home, and Tucker knew there was something wrong after all. “He said, ‘Let’s sit out by the pool,’ ” and Parker told him the whole story. Secretly, the Colonel’s employee rooted for Elvis. “I thought, well, by God, Elvis showed him this time. For a change he stood up.” But Parker was somehow sympathetic, too—craving a kind word and a compliment. No manager had ever accomplished what he had, or taken a star to such heights. Now he’d made a once-in-a-lifetime deal for a client who didn’t even care, a client who was surely slipping out of his grasp.

“He asked me, ‘Gabe, would you get my bed turned?’ And I said, ‘Sure.’ ” Afterward, Tucker rolled it out beside the pool for him, helped him into it, and made him as comfortable as he could. He wondered if Parker wasn’t sick after all. Then he plugged in the outside phone.

The two old friends sat there for a minute reminiscing about how far - they’d come in twenty-five years. Soon, the phone started ringing nonstop—Elvis still hadn’t reported to the studio. “They was on him somethin’ awful. I never heard such cussin’ and carryin’ on, and he didn’t usually do that. Finally, I said, ‘Colonel, why don’t you tell ’em to kiss your ass? You got all the money you need. You can just tell everybody that you managed the highest-paid truck driver in the world.’ And he laughed, but he said, ‘Goddamn, Gabe, that ain’t funny.’ ”

It was March before Elvis gave in. The caravan left Memphis so late in the day that they needed to drive straight through, without the usual night’s rest in Amarillo or Albuquerque. But during a brief stop at a motel for a shower and a change of clothes, Elvis took Larry aside. Intellectually, he understood all the books Larry gave him, but he’d never had the kind of profound spiritual experience they described.

“I explained to him that it had nothing to do with an intellectual perception,” Geller says, “that it was more of an emotion, a surrendering of the ego to God.” They continued their discussion on the drive, Elvis steering the mobile home and Larry riding shotgun, the other entourage members in the back and following in separate cars.

They drove the rest of the night, and it was well into the next day before Elvis realized he’d gotten separated from the rest of the group. Elvis told Larry he was glad they were lost—“I need to be away from everyone, because I’m really into something important within myself.”

By that time, they were in Arizona, near Flagstaff, approaching the famous San Francisco Peaks, in the land of the Hopi Indians. It was coming on dusk when Elvis peered into the electric-blue sky and suddenly said, “Look, man! Do you see what I see? What the hell is Joseph Stalin doing in that cloud?” Larry said he saw it, too, and then the image dissolved back into a fluffy cloud again.

Suddenly, Elvis pulled the mobile home over and, jumping out, yelled, “Follow me, man!” Then he took off into the desert. When Larry caught up with him, Presley had tears rolling down his cheeks. “It happened!” Elvis said, hugging his friend. “I thought God was trying to tell me something about myself, and I remember you saying, ‘It’s not a thing in your head. It has to do with your heart.’ I said, ‘God, I surrender my ego. I surrender my whole life to You.’ And it happened!” The face of Stalin had turned into the face of Christ.

“It was like a lightning bolt went right through him,” Geller recounts. “He said, ‘Larry, I know the truth now. I don’t believe in God anymore. Now I know that God is a living reality. He’s everywhere. He’s within us. He’s in everyone’s heart.”

When they returned to California, Elvis took his friend into the den of the rental home on Perugia Way and told him he’d made a decision. After such an intense experience, he couldn’t go back to making “teenybopper movies” again. He wanted to quit show business and do something important with his life. “In fact, Larry,” he said, “I want you to find me a monastery. I’m not making a move until you tell me what to do.”

Geller froze and then, thinking fast, told Elvis he could use his vision to make a difference in his films and in his records. “You’ve got the greatest career in the history of show business!” Geller told him. “You are the legend of them all! You are Elvis!”

Geller’s words found their target. “He got that gorgeous grin on his face, and he said, ‘Yeah, well, to tell you the truth, I can’t imagine Priscilla next to me in some monastery, raking leaves.’ ” But Larry knew the conversation meant trouble. At the word monastery, collective groans rose from the other side of the louvered doors. Says Geller, “I realized that five minutes later, Colonel Parker would know everything, and the little wheels in his head would start to turn.” Soon, Parker would also learn about Elvis’s involvement with an ecumenical movement called the Self-Realization Fellowship, based in Pasadena and run by a disciple of Paramahansa Yogananda named Sri Daya Mata. And the Colonel certainly wouldn’t like that.

The fallout started several weeks afterward on the soundstage of Harum Scarum. To keep their relationship strictly business, the Colonel made few appearances on the movie sets, and when he did, he held court, saying, “Where’s a chair for the Colonel?” and expecting the Memphis Mafia to snap to attention, bringing him water and lighting his German cigars with the yellow tips. Geller was always uncomfortable when he added, “And bring a chair for Larry . . . You sit with me, Larry.”

“He knew that I had Elvis’s ear, and that Elvis was changing, and he couldn’t figure me out.” Sometimes, Parker even asked Geller to give him a haircut or invited him to share the whirlpool bath at the Spa in Palm Springs. It was always tense between them, but this day, Geller knew the Colonel had a different tack, and he wasted no time in getting to it.

“Larry,” he began, “I think you’ve missed your calling. You’re tall, and have such a commanding presence. I can see you dressed up in a tuxedo, standing on the stage. You have the quality to hypnotize people.”

By now, the Colonel had reinstalled his pipeline, Joe Esposito, who shared co-foreman duties with Marty Lacker. Elvis seemed resigned to the arrangement, telling Geller he knew the Colonel had been taking care of Joe all of those years, and that he didn’t care. Several days later, with the picture completed, Esposito reported that Parker had called and wanted his client to come over to MGM right away. Geller was blow-drying Elvis’s hair in the bathroom, and they stopped and gathered the rest of the guys and piled into two cars.

“We went over to the lot,” Geller says, “and about ten minutes later, Elvis walked out. We knew he was ticked. He got in the car and he said, ‘That motherfucker, man. He accused me of being on a religious kick. My life is not a religious kick. I’ll show that fat bastard what a kick is.’ He fumed for days.”

It was as if his resentment about everything had finally boiled over—his embarrassment about the scripts, his frustration at seeing his music reduced to pabulum, and Parker’s constant interference. “The Colonel really cares about me? He’s supposed to take care of the business end and that’s it. He’s not a personal friend, he’s my manager, and he’d better stay that way!”

Parker never criticized Elvis to any of his acquaintances, but now he drew a radical plan of action. While the Colonel had always directed almost every facet of Elvis’s existence, he rationalized that he had involved himself only in Presley’s professional affairs. With both his client and their partnership disintegrating, he would rule with an iron fist.

This was the right thing to do, he told himself, since Elvis was incapable of taking care of himself. Besides, they had wrung almost every dollar out of Hollywood; Wallis and Hazen strongly believed the next movie, Paradise, Hawaiian Style, would be, as Hazen termed it, “Elvis’s last good picture” and would go for only one more, Easy Come, Easy Go, once their deal ran out. Charles Boasberg, president of Paramount’s distributing company, had sounded the final knell, writing Wallis that Frankie and Johnny, a United Artists film, “is dying all over the country, and this is his second poor picture in a row. If it weren’t for you lifting him up with some good production in your pictures, Presley would be really dead by now.”

Parker fought Joe Hazen on virtually every clause of the new contract, and while Wallis defended him (“I think the Colonel has kept his word with you and has shown fine spirit characteristic of him,” he wrote to his partner), Hazen at one point called Parker’s changes in the agreement “the height of duplicity . . . he is trying to get his and we have ours.”

But the Colonel also saw it as a triumph.

“One day,” remembers Marty Lacker, “Elvis came up to me and said, ‘The Colonel wants you to take him to Palm Springs.’ I had never done that before, and I thought it was a very strange request, considering our relationship.

“I went over to his office, and I remember I had on a black pullover sweater. The Colonel looked at me and said, ‘You’re not dressed right. Let me give you a shirt.’ He opened up a closet and pulled out this ugly, old man’s yellow-and-white-striped shirt. And it had a cigar burn on the front. I said, ‘Colonel, I don’t want your shirt.’ He said, ‘You sure?’ And he put it back in the closet.

“We started driving, and we got about a half hour out of Palm Springs, and we hadn’t said a word to each other. He was sitting next to me in the front seat. All of a sudden, he started chuckling, and he said, ‘Boy, I showed those goddamn Jews, didn’t I?’ Just out of the blue. Then he chuckled again. Now, I’m saying to myself, You no-good bastard. You’ve got to know I’m Jewish. I wanted to take that car and head it into a pole, figure out how to kill him without hurting myself.”

In 1966, Parker would persist in wooing the producers for another film, issuing a “Snowmen’s League Annual Report,” a tongue-in-cheek document listing bogus expenses, grosses, and profits. At the end, Parker inserted a photo of Elvis and Wallis shaking hands, onto which he had pasted a bizarre likeness of himself standing behind them and wielding a machete. “If you don’t sign a contract,” it seemed to say, further suggesting that only he had the power to sever ties, “I’ll cut off your arm.”

By now, though, the producers were immune to the Colonel’s ploys. Easy Come, Easy Go would almost not be released, Paramount believing it was doubtful the picture could recoup its cost. After Paramount backed off its advertising campaign and Parker relentlessly complained that he had spent too much of his own money to promote it, Wallis sent him a check for $3,500. But the veteran filmmaker would never do business with him again.

Things were nearly as dismal at MGM. The prefab method by which “the Elvis movie” was assembled had become painfully obvious, with its tiny production budgets and lack of location shots for the films supposedly set in Europe and the Middle East. The grosses were also way down, and the plots had deteriorated to cartoonlike absurdity. Harum Scarum, released in late ’65, had been so ridiculous, the Colonel suggested, that only a talking camel could save it by making the picture an intentional farce. Parker had always told Elvis never to admit he’d made a mistake, but the manager doubted his own judgment in going along with Sam - Katzman’s eighteen-day shooting schedule. It would take “a fifty-fifth cousin to P. T. Barnum to sell it,” the Colonel said, and the best thing to do was “book it fast, get the money, then try again.”

Before long, rumors swirled in Tennessee that Elvis was retiring, or that he was looking to hire another manager, or that the Colonel himself was ready to quit managing his star. In February 1966, the Colonel got on the phone to the Memphis Commercial Appeal and explained that there wasn’t a word of truth to the rumor, diffusing the situation with bravado, saying, “Heck yes, I would retire and so would my boy—if we received enough money to retire . . . We have contracts for fourteen additional motion pictures to be made over a period of several years.”

Still, Parker’s judgment remained cloudy. His code of loyalty made him stick with inappropriate directors, including Norman Taurog, a quasi-hack best known for directing Boys Town with Spencer Tracy in 1938 and Elvis’s own Blue Hawaii. Taurog had made a string of Elvis’s films, and Parker requested him more often than his talent—or his health—warranted. In meeting with Irwin Winkler, who came aboard as the producer of Double Trouble, the nearly seventy-year-old Hollywood veteran admitted he was blind in one eye and couldn’t see well enough to drive. Taurog would be completely sightless within two years of finishing Double Trouble, during which time he would direct two more Presley pictures, Speedway and Live a Little, Love a Little, which would rank among Elvis’s most disappointing efforts.

Even the die-hard fans grumbled that the films weren’t opening at the choice suburban movie houses, but at drive-ins. Worse, they relied on the same old formula—Elvis as a virile stock car racer, nightclub singer, or crop duster, saddled with a philandering, bumbling sidekick, and searching for true love through implausible dialogue and hackneyed songs. The president of the Hampshire, England, Elvis Presley Club wrote that the movies were “an insult to Elvis and fans.” Another pleaded to Wallis that someone must help Elvis now “when his career is beginning to falter,” while an even more prescient voice opined, “I realize that there is not much you can do if Elvis doesn’t care, and sometimes I doubt that he does.” Despite the fact that exhibitors would soon claim that something must be “radically wrong” with Elvis, judging from his appearance, a lucrative movie offer came from Japan. But Parker turned it down, saying Elvis was booked through 1969.

Byron Raphael used to ask the Colonel how he could be so strong, refusing certain offers and holding out for unprecedented money elsewhere. Parker explained it was because he had a three-tiered client—the real reason he hadn’t taken on anyone else to manage. “Byron,” he said, “we don’t need the movie business. If we couldn’t do movies, we could do personal appearances for $50,000 a night. And if we couldn’t do personal appearances, we could do records. We have gigantic record sales. I wouldn’t do it otherwise.”

But in 1966, RCA again refused the Colonel’s request to sponsor a big tour of personal appearances. He’d asked for $500,000 this time, and as RCA’s Norman Racusin puts it, “I did not know who the $500,000 was going to.” The company had also become concerned about slipping sales—as musical tastes changed, an album that might have had a standing order for 2 million copies was down by half—and RCA would soon reduce Elvis’s guaranteed advance. But Parker had other plans for Elvis. If he could hold him together.

The first order was to get him focused. For that, the Colonel sent a stronger message to Larry Geller.

One Sunday, he invited Geller and his wife and children to come to Palm Springs and spend the day at the house. After a swim, Parker asked Larry inside, where he began to probe him about his spiritual beliefs. The telephone rang, and Geller got the strange feeling from the Colonel’s opaque mumbles that the conversation might have been about him.

“He looked at me and he glanced away, and he said ‘Yes, yes, right now. Well, yeah, right.’ But I dismissed it, because I had no reason to be suspicious.”

Parker hung up and suggested they gather the kids and go to Will Wright’s Ice Cream Parlor. Afterward, the Gellers made their good-byes and returned to Los Angeles. “The minute I drove into the driveway, I saw the back door open,” Larry remembers. “It was a precision strike.”

The intruders had not taken items of monetary value, but Geller’s files on metaphysical topics—parapsychology, astrology, palmistry, and numerology—along with tapes of music from the Self-Realization church. His clothes, too, were gone. Garbage was dumped upside down in the living room.

Devastated, Geller piled his frightened family in the car and drove to see Elvis. “He shook his head back and forth a few times and said, ‘All right, we know who did this.’ ” Though Presley set the Gellers up in a hotel until they were ready to return home, Elvis downplayed the incident, saying that at least no one was hurt. But it scared them both. Says Larry, “We just tried to repress it.”

With Geller seemingly defused, Parker now attacked the second order of business: getting Elvis married.

The strange press release that Parker had written for 1961’s Wild in the Country shows that the Colonel had been thinking of this for a long time. “During the making of [the film],” Parker wrote, “Elvis was asked if the Colonel would object if Elvis married.”

“ ‘The Colonel would have nothing to say about it,’ Elvis replied with more than usual emphasis. ‘I probably would talk it over with him as a friend and as a man I respect, but never in the sense of asking his permission.’

“ ‘When the boy wants to marry, I hope he’ll ask me to help him do it,’ ” Parker said.

“Like a wise father,” the press release went on, “Colonel Parker takes an interest in the girls Elvis escorts, but doesn’t interfere. He probably would step in if he thought Elvis were making some dreadful mistake, but it would be as a counselor, not as a commanding officer.”

In 1966, however, there was another commanding officer to consider. Priscilla was almost twenty-one now, and her stepfather, the newly promoted Lieutenant Colonel Beaulieu, was sounding off about Elvis’s promise to make her his wife. He’d called in recent months and uttered what Elvis took to be some mild threats, and Parker didn’t know how long he could hold him off. If Elvis reneged, and Priscilla went to the papers, it could look very bad—the headlines would scream how he’d harbored an underage girl and broken her heart.

Priscilla was beginning to think he was never going to marry her, especially as he was dating Ann-Margret, who told reporters she was in love with Presley but didn’t know if they would marry. A scared Priscilla had flown out to Hollywood to try to break up the romance, but the Colonel had sent her home to Memphis so no one would ask questions about their relationship, too.

Suddenly, everyone was thinking seriously about marriage. The Colonel figured it would end Elvis’s obsession with religion, keep him away from Ann-Margret and her smart young team of managers, and stem Elvis’s growing fixation with guns and law enforcement. Priscilla hoped it would make him grow up—why did he need all those guys around for slot car races and water balloon fights, anyway? And Vernon, who still pretended to take care of Elvis’s personal business (“My daddy doesn’t do anything,” Elvis had once accurately answered when asked Vernon’s profession), would be happy if it quelled his son’s incessant spending. At the end of 1966, Elvis would negotiate to buy a $300,000 ranch in Mississippi and blow a fortune on trucks, horses, and trailers for his friends. Parker liked to see Elvis burn through his money—it kept him working—but it made Vernon’s head spin.

Yes, they agreed, Elvis must get married. Furthermore, Elvis shouldn’t be so remote; he needed to stay in closer touch with the ol’ Colonel. And so in September ’66, Elvis leased a home in Palm Springs, where he spent Thanksgiving with his manager. But the stress was taking its toll. On the way home to Memphis, Elvis heard “The Green, Green Grass of Home” on the radio and broke down when he arrived at Graceland, telling Marty Lacker, “I walked in the door, and I saw my mama standing there. I saw her, man.”

Just before Christmas, Elvis proposed to Priscilla. A vague date was set for the following year. Elvis couldn’t find it in him to tell Ann-Margret and simply stopped taking her calls.

With his skewed moral center, Parker believed that forcing Elvis to marry was an honorable move, even if Elvis himself was not emotionally committed. “When I fall deeply in love it will happen,” he’d told Hedda Hopper five years earlier. “I’ll decide on the spur of the moment, but it won’t be an elopement . . . but a church wedding.”

When Elvis reported for wardrobe fittings for Clambake, his twenty-fifth film, in March of ’67, the studio was shocked to discover that he had ballooned to 200 pounds, up 30 from his usual 170. “He ate out of depression,” says entourage member Jerry Schilling. “The movies were boring to him, and when he didn’t have a challenge, he always got depressed.” Parker was furious. Elvis began trying to melt the weight off with diet pills, but on top of the sleeping tablets and his usual arsenal of mood-altering drugs, the medications made him dizzy.

One night at his new rental house on Rocca Place, Elvis got up to use the toilet and tripped over a television cord in the bathroom and hit his head on the sunken tub. By morning, he had a golfball-size lump, and he was woozy when he staggered out of the bedroom and asked the guys to take a look. Esposito phoned the Colonel, thus setting in motion the events that led to Parker’s most egregious attachment of Elvis’s earnings.

By the time the Colonel arrived at the house, along with several white-uniformed nurses and a doctor carrying portable X-ray equipment, Elvis could barely hold his head up. The diagnosis was a mild concussion, but the start of the movie would have to be delayed by several weeks.

“The Colonel took us out in the hall,” Marty Lacker remembers, “and he said, ‘Goddamn you guys, why do you let him get this way? He’s going to mess up everything! They’ll tear up the contract!’ ”

Then he turned to Larry Geller. “Get those books out of here right now!” he bellowed. “Do you understand me? Right now!”

Afterward, says Lacker, “the Colonel went back in and talked to Elvis, and he said, ‘Here’s the way it is. From now on, you’re going to listen to everything I say. Otherwise, I’m going to leave you, and that will ruin your career, and you’ll lose Graceland and you’ll lose your fans. And because I’m going to do all this extra work for you, I want fifty percent of your contract.’ ”

Parker prepared a new agreement, backdating it to January 1. In setting down terms for a joint venture, the Colonel wrote that he would continue to collect a 25 percent commission on Elvis’s standard movie salaries and record company advances, but All Star Shows would now receive 50 percent of profits or royalties beyond basic payments from both the film and the record contracts, including “special,” or side, deals. The commission would be deducted before any division of royalties and profits. Their merchandising split would remain the same.

Lacker was surprised at how quickly Elvis had okayed such an arrangement, but the foreman didn’t know about the clinical depths of Elvis’s depression, nor about a conversation that had taken place between Parker and Presley sometime the year before.

They were talking about Sam Cooke, the great soul singer who died in a shooting outside a hooker’s seedy motel room in 1964. Cooke had also recorded for RCA—in fact, his live At the Copa album was released the month of his death. But it wasn’t the manager of L.A.’s Hacienda Motel who killed him, as the press reported, Parker told Elvis. The Mafia got him. Cooke was stepping out of line, the Colonel said, getting involved in civil rights, spouting off about things he shouldn’t. He was warned, but he wouldn’t shut up. Word came down and the hit was made.

The mob wasn’t gangsters in the streets anymore, Parker explained. It was heads of corporations like RCA, the East Coast, Sicilian families—men whose last names ended in vowels, men with uncles called Jimmy “the Thumb.”

“Colonel told Elvis, ‘You’ve got to behave yourself. You can only go so far,’ ” says Larry Geller. “And Elvis knew the Colonel was a dangerous enemy.”

A week or so after the fall, when Presley regained his strength, Parker called a meeting at Rocca Place. Priscilla and Vernon had flown out from Memphis, and along with Elvis and the guys, they sat around the living room as Parker rolled out a list of changes: one, Joe Esposito was to be the lone foreman. Two, no one was to talk about religion to Elvis, and Geller could no longer be alone with him. And three, there was too much money going out. Everyone’s salary would be cut back, and several people had better start looking for jobs.

In the end, no one was fired, and only one person left voluntarily, when Larry Geller quit the following month. But the guys had never seen Elvis so docile. He never took his eyes off the floor, and he never spoke up.

At 9:41 on the morning of May 1, 1967, Elvis and Priscilla were married by Nevada Supreme Court Judge David Zenoff in a small, surprise ceremony in Milton Prell’s suite at the new Aladdin Hotel in Las Vegas. “She was absolutely petrified, and Elvis was so nervous he was almost bawling,” the justice remembers. Afterward, owner Prell laid out a $10,000 champagne breakfast with suckling pig and poached salmon, and then the couple flew to Palm Springs on Frank Sinatra’s Learjet to begin their honeymoon.

As if it were the Colonel’s own wedding, Parker arranged every detail. “It was the Colonel who got the rings, the room, the judge,” Priscilla later said. “We didn’t do any of that. It was all through his connections. We wanted it to be fast, effortless.” Which meant she and Elvis also allowed the Colonel to pick the attendants and the guests, who numbered fewer than twenty. Most of the Memphis Mafia were excluded from the ceremony—a painful slight that would leave bruised feelings for years—but invited to the breakfast, where they mingled with Parker’s gambling buddy, the comedian Redd Foxx.

Larry Geller, whom Elvis had once asked to be best man, read about the wedding in the newspaper. Stunned, he thought back to the events of the past month. Parker had taken charge of everything in Elvis’s life except the one aspect he should have addressed: Presley’s drug use.

Grelun Landon, who worked with the Colonel from 1955 on, first as a vice president of Hill and Range and then as an RCA publicist, says that Parker himself didn’t know about the pills during the MGM years, despite Elvis’s ever-present “makeup” case. But others insist that can’t be true—the Colonel was informed about everything that went on—and though their meetings were infrequent, there was no way he couldn’t have recognized the erratic behavior and abnormal perspiration of an addict, even one whose dependence was on prescription drugs, not street narcotics.

But just as several of the entourage members were in denial about their own drug use, Parker, according to his friends, refused to believe that Elvis was truly in trouble. A more plausible explanation is that in the days before the Betty Ford Clinic, the Colonel didn’t know where to take him for discreet, effective help and loathed risking the loss of work if the truth got out. As a man who spent his whole life covering things up, Parker believed the decent thing was to conceal Elvis’s “weakness.”

Just as Elvis turned increasingly to drugs in periods of stress, Parker, as his difficulties mounted, visited the gambling tables of Las Vegas for the addictive element of excitement and escape. For many gamblers, the satisfaction—even the thrill—is in losing, not winning, since for pathological gamblers with an impulse control disorder, the game is never about the acquisition of money, but about the action itself. Gambling fed the obsessive twins—Wisdom and Folly—of Parker’s personality, which made him by turns calculating and reckless, self-protective and self-destructive.

Parker’s losses were now becoming increasingly apparent to his business associates, who saw him as a chronic gambler. Since 1965, he’d been asking for money early on the film contracts, and new RCA president Norman Racusin was well aware that Parker “had a penchant for the tables,” as the label had assigned Harry Jenkins to keep the Colonel happy. That meant Jenkins spent an inordinate amount of time sitting at the craps tables with Parker in Vegas, the Colonel intoning, “Let’s go down to the office” as his signal for some action.

Jenkins hoped that RCA would reimburse him for the losses he sustained when Parker urged him to throw in a few chips. But the label had no such intention, since it was already occasionally taking care of the Colonel’s debts. Though Parker grossed unfathomable sums of money, little of it came in steadily. In between deals, he began calling on Hal Wallis, the Morris agency, and RCA to cover him, the casinos knowing that someone was always going to be good for his money. If not, they gave him credit, or wrote it off as a favor.

“I’m sure there was an awful lot going on,” says Parker’s acquaintance Dick Contino, the accordionist who was courted by the mob early in his career and remained a favorite of Sinatra. “It would be an obvious thing. If you’ve got a problem financially, these guys don’t write notes—they ask you what you need. If they like you, you got it. Money is nothing, but respect, everything. My guess is that they asked for their favors in return and got them, maybe unbeknown to Elvis. I wouldn’t criticize Tom for it. Why not?”