4

A BRIEF SURVEY OF CLIMATE CHANGE

The decisive factor for the violence and other social problems that may result from climate change is not the rise in average temperatures or sea levels over the coming decades (these consequences are already with us and will become more intense to a degree that will vary with the scale and drama of the change); nor is it the extent to which climate trends are manmade or represent a natural fluctuation such as has often happened before in the history of the planet.

As a social scientist, I shall base myself in this section mainly on the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), since these were subject to pre-publication policy debates that filtered out anything thought to be exaggerated. As is well known, such negotiations among governments are concerned less with the truth than with interests – for example, with the obligations that a particular finding might entail for individual countries. What emerges at the end of this process, after it has brought the scientists involved to the brink of self-suppression, is therefore the most conservative imaginable assessment. Since the policymakers are engaged in warding off obligations and constraints, the analysis is geared to that which is virtually beyond doubt and contains the least possible speculation.

Furthermore, the public discussion has mostly overlooked the fact that the IPCC reports make scant use of models, prognoses and assumptions but rest their case on existing measurements of rising temperatures and ocean levels or shrinking glaciers. The reports are therefore empirically focused more on the past and present than on the future, leaving what will happen much more open the further they look ahead. In most regions in question, however, the effects of climate change are already palpable, even without the complicated measurement methods and results of oceanologists, meteorologists and palaeobiologists. So, from today’s vantage point, what are the main aspects and likely consequences of climate change?

The IPCC report published in February 2007 assumed with 90 per cent probability that the currently observable climate change is the result of human activity, mostly caused by emissions of so-called greenhouse gases throughout the period since the Industrial Revolution. Fossil fuel use for industry and transport produced the CO2, while agriculture (especially livestock farming) emitted the methane and nitrous oxide. Both carbon dioxide and methane levels in the atmosphere are now higher than at any time in the past 650,000 years.

The warming of the global system is beyond all doubt, the authors write; it can be read from the increase in air and ocean temperatures, the melting of glaciers and permafrost, and the rise in sea levels. Average yearly temperatures since 1850 (the year when measurements first began) show that the eleven warmest years were all in the period from 1995 to 2006.1 Ocean temperatures have increased down to a depth of 3,000 metres.2 And the rise in sea levels has been compounded by the effects of climate change, since higher temperatures enlarge the water surface and the melting of polar ice and glaciers increases the amount of seawater. This is one of the simplest interactions; the fact that there are much more complex ones, some with feedback mechanisms, makes prognoses intrinsically difficult. The observable effects of climate change already include displaced rainbelts and more frequent rainfall, desertification and extreme weather events such as heatwaves, storms and heavy downpours, including in regions where they have not previously existed.3

The last time that known temperatures in the polar region were so high was 125,000 years ago. The IPCC forecasts that, at present rates of emission, average global temperatures will rise by 0.2 degrees Celsius per decade – more if emission rates continue to increase. The various scenarios would result in a temperature increase by the end of the century ranging from a minimum of 1.1 degrees to a maximum of 6.4 degrees. What that implies is not a gradual drift but sharp changes in ways of life. The rise in ocean levels will be between 18 and 59 centimetres.

The future will bring a further melting of ice cover, glaciers and permafrost; typhoons and hurricanes will occur more frequently and in unusual places; rainfall will become more likely in the North and less likely in the South; and ocean currents will probably change direction as a result of interaction among these processes.4 Although, for understandable reasons, it is not possible to say exactly what will happen when and where, it is evident that all this will have consequences for plant and animal life, and therefore for human nutrition and survival chances.

In April 2007 the IPCC published its conclusions about the highly varied impact that climate change is expected to have on societies around the world, depending not only on its direct consequences but also on the capacity of each society to cope with them. Northern Europe, for example, with its high living standards and good levels of nutrition, is well protected against disasters and in a position to repair any material damage. But a region like the Congo, which already suffers from poverty, hunger, deficient infrastructure and violent conflicts, will be hit much harder by environmentally determined negative changes.

A number of factors come into play. The worst-affected countries will probably be those with the least capacity to deal with the consequences, while the ones that will escape most lightly, or even profit from the climate changes, will be the ones with the greatest resources to cope. What is more, the hardest-hit populations will probably be those with the lowest greenhouse gas emissions in the past, whereas the big polluters will suffer the least from the consequences. Here we see the signs of a historically new global injustice: climate change will deepen the existing asymmetries and inequalities of life chances.

Africa is the continent most vulnerable to climate effects, on account of its widespread poverty and tendency to political chaos and the presence of violent conflicts in a number of regions. The IPCC predicts that, by the year 2020, a total of 75 to 250 million people will not have sufficient access to safe drinking water. In some regions only a minority of the population has this today: 22 per cent in Ethiopia, 29 per cent in Somalia, 42 per cent in Chad.5 Agriculture will also suffer from lack of rainfall and declining groundwater levels; some estimate that by 2020 as much as half the normal yield will be lost in certain regions. Nor does the state of fishing look any better; species are dying out in lakes and rivers, while coastal regions are at risk from flooding.6 Diseases such as malaria and yellow fever will spread in previously unaffected areas in East Africa and elsewhere.

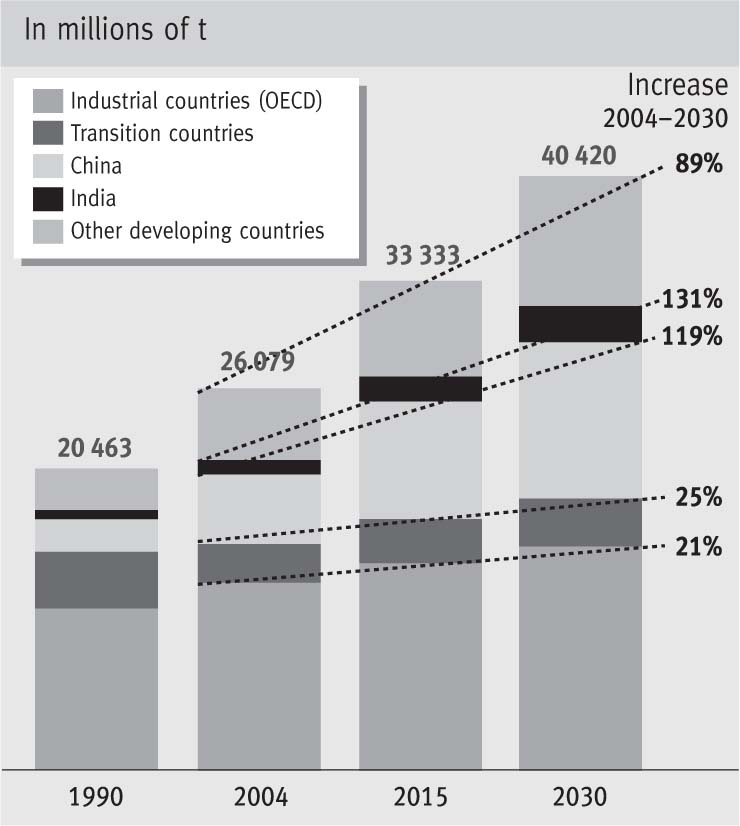

Figure 4.1 CO2 emissions by region, in millions of tonnes (including trapped)

Source: International Energy Agency.

In Asia, as many as a billion people may be affected by shortages of drinking water by the year 2050; and in addition the melting of Himalayan glaciers will lead to ecological changes, floods and avalanches. Food production may rise in many parts of East and SouthEast Asia, but fall in a number of other areas (Central and South Asia). Diarrhoeal diseases due to flooding will increase, and rising water temperatures will make cholera epidemics more likely in coastal regions. Coping capacities vary from country to country, but are often completely inadequate.

Australia and New Zealand will also suffer (to some extent they already do) from considerable water problems. The main effect here of climate change will be on biodiversity. But, since both countries have good capacities for controlling and coping with disasters, the social consequences will not be as great as in Africa or Asia.

South America is affected by falling groundwater levels and desertification. Clearing and burning of rainforest, which results in soil erosion, will accentuate the effects of climate change, as will the decline of biodiversity. Coastal regions will be at risk of flooding as in all other parts of the world. Capacities for controlling and coping will vary from country to country.

In the polar regions the social consequences of climate change will be comparatively minor, since scarcely anyone lives there. On the other hand, the effects of warming will be especially acute. The melting of sea ice, the thawing of permafrost and increased coastal erosion will have an impact not only on human and animal life but also on sea levels, evaporation, and so on. Warming will have a number of positive effects: improved land use potential, greater access to raw materials beneath the ice, and the opening of new shipping routes. But conflicts over sovereignty claims and exploitation rights are already beginning to loom.

The population of island groups in the Caribbean and the Pacific is at massive risk from climate change – not only because it will lose income from fishing and tourism, but above all because many islands will become uninhabitable. Compensation claims will be problematic, and, as we know from history, resettlement will carry a major potential for conflict.

For Europe the consequences of climate change will be relatively benign, although melting glaciers, extreme weather events, landslides and floods will not be good for agriculture and the tourism industry. Here too a North–South gap will be apparent. Whereas Northern Europe may benefit from new possibilities for growing fruits, cereals, wine, and so on, Mediterranean regions will be increasingly liable to drought and water shortages. In general, however, European countries have an excellent capacity for limiting or offsetting the effects of climate change, or even for turning them to advantage. Countermeasures such as improved coastal defences have already been introduced. Here the social consequences will be mainly indirect, especially in relation to pressure on borders, greater insecurity, and so on.

The same is true of North America. Agricultural prospects will improve in many regions, but many others will face flooding, water shortages, worse conditions for winter tourism, and so on. Heatwaves may also become a common problem, and coastal areas will suffer from hurricanes and floods. Here, as in Europe, measures are already being taken to prepare for the future.7 As for coping capacities, the same remarks apply as for Europe, with regional variations.

The overall picture, then, is of an uneven distribution of the social consequences of global warming. The resulting injustice, both geographical and generational, contains a serious middle-term potential for conflict.

TWO DEGREES MORE

Climate researchers are agreed that the social and economic consequences of climate change may still be controllable, if global warming can be restricted to 2 degrees in excess of levels before the industrial age – that is to say, 1.6 degrees higher than today. As Fred Pearce calculates, there were 600 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere at the end of the last ice age, and that level remained more or less constant right up to the Industrial Revolution. Manmade emissions have since raised the figure to 800 billion tonnes, and without further acceleration it would probably rise no higher than the tolerable maximum of 850 billion tonnes. At present, however, another 4 billion are being added each year, which means that the sustainable maximum will be reached in the next ten years – without even allowing for higher rates of emission in newly industrializing countries. So, to keep the temperature rise to 2 per cent is a realistic goal only if global emissions ‘peak within five years or so, falling by at least 50 per cent within the next half-century, and carrying on down after that’.8 Whether one thinks this achievable will depend on one’s confidence in the power of collective reason.