8

CHANGED REALITIES

In the rolling present, it is difficult to decide whether one has reached a critical point in a process: When does a decision become irreversible, and when does the further pursuit of a strategy spell disaster? When was that point reached on Easter Island? From today’s vantage, we can give an answer: it was when so many trees had been felled that the forest could no longer regenerate. At the time, the state of environmental knowledge – the mental framework that dictated how to deal with nature – probably meant that people could not have ‘known better’.1 Jared Diamond is therefore on the wrong track when he asks what Easter Islanders thought when the last tree came crashing down. The fateful moment is not at the end of a process of destruction, but at the point when no one can see that what they are doing is destructive.

The Easter Island disaster did not begin when the last tree fell, any more than the Holocaust began when the last gas chamber was installed at Auschwitz. Social disasters commence when false decisions are taken: that is, in the case of Easter Island, when distinction and status rules required the use of wood to produce statues, or, in Nazi Germany, when pseudo-scientific assumptions about human inequality passed into laws and directives. But how present could the fate of the Jews have been in people’s minds, at a time when no one had yet thought of developing systems for the annihilation of groups of human beings?

SHIFTING BASELINES

Besides the storms, it was the year that the rainforests got no rain. Forest fires of unprecedented ferocity ripped through the tinder-dry jungles of Borneo and Brazil, Peru and Tanzania, Florida and Sardinia. New Guinea had the worst drought for a century; thousands starved to death. East Africa saw the worst floods for half a century – during the dry season. Uganda was cut off for several days and much of the desert north of the region flooded. Mongol tribesmen froze to death as Tibet had its worst snows in fifty years. Mudslides washed houses of the cliffs of the desert state of California…. In Peru, a million were made homeless by floods along a coastline that often has no rain for years at a time. The water level at the Panama Canal was so low that large ships couldn’t make it through. Ice storms disabled power lines through New England and Quebec, leaving thousands without power or electric light for weeks. The coffee crop failed in Indonesia, cotton died in Uganda and fish catches collapsed in the eastern Pacific. Unprecedented warm seas caused the tiny algae that give coral their colour to quit reefs in their billions across the Indian and Pacific Oceans, leaving behind the pale skeletons of dead coral.2

A report from the future, say 2018, when the planet has warmed by another degree? Wrong. All the above events took place in one year in the past, in 1998, and were associated with a particular climate event, El Niño. They were not the result of global warming, although it is assumed that such things will occur more often in the future on account of climate change. The events of 1998, to which one might add many more – from 1999, 2000, 2001, and so on – serve mainly to demonstrate that people develop a forgetful attitude to disasters that did not affect them and were seen only in the media.

There have been other media events in the last ten years, such as the massive fire in the Borneo rainforest that created a smog over a provincial capital, Palangkaraya, for months in 1997–8 and discharged 800 million to 2.6 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere;3 or the series of tornadoes that devastated Oklahoma in May 1999, killing forty, injuring 675 and causing damage estimated at $1.2 billion. There have also been spectacular hurricanes: Mitch, for example, cost 10,000 lives in Central America in 1998; Katrina buried a large Western city in water for the first time when it hit New Orleans in 2005; and Wilma broke three records, as the last in the 2005 season of twenty-two storms (the largest number ever known), the most powerful Atlantic hurricane ever measured, and the most costly in terrestrial damage ($29 billion).

Such extreme weather events are not new, but in recent years they have become more frequent and larger in scale. Yet people come to see them as normal, their attention slackening as the events become less newsworthy. Something that has little to do with nature is increasingly seen as ‘natural’.

‘Shifting baselines’ is how environmental psychologists refer to the fascinating phenomenon that people always consider ‘natural’ the surroundings that coincide with their lifetime experience. Perception of changes in the social and physical environment is never absolute but always relative to one’s own observational standpoint. So, the present generation has at best a vague or abstract notion of the fact that, in previous generations, not only the constructed lifeworld and infrastructure but also the natural environment was different; that, for example, meadow and heath landscapes are products of bygone deforestation, or that erosion problems in Central Europe have been known ever since the massive clearances of the Middle Ages.4

But we do not have to go back so far in time; the passage from one generation to the next is usually enough to display massive changes in how the environment is perceived. We have already mentioned the pioneering study of fish stocks and fishing grounds in different generations of Californian fisherfolk, the results of which are quite astounding. The researchers asked a sample from three generations where they thought that stocks had dwindled, which species they mainly caught in their nets, what was the size of their largest catch, and how large was the mightiest fish they had ever hauled aboard. The youngest group of respondents was aged between fifteen and thirty, the middle group between thirty-one and fifty-four, and the oldest fifty-five and above.5 A full 84 per cent agreed that stocks had been declining, but there was blunt disagreement about which fish species were disappearing and where. Respondents in the oldest group named eleven species and the middle group seven, while the youngest mentioned only two that were no longer appearing in their fishing grounds.6

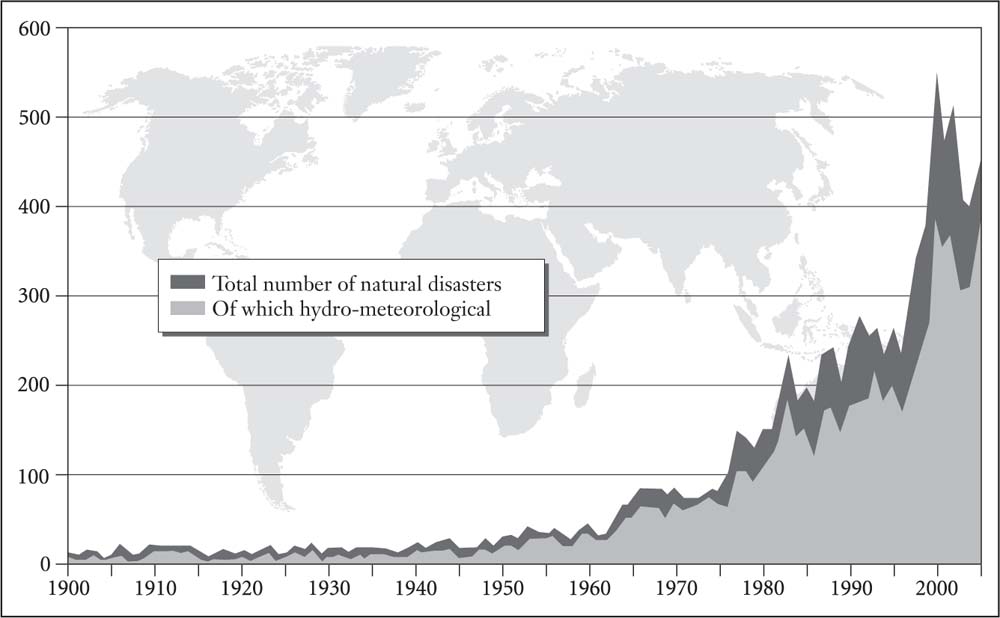

Figure 8.1 Number of extreme natural events and percentage involving weather-driven disasters

Source: EM-DAT (the OFDA/CRED international disaster database) (www.emdat.be/database), 3 April 2006.

The youngest also had no idea that, where they went every day to fish, there had not long ago been an abundance of great white sharks and goliath grouper, as well as pearl oysters. The same differences were apparent in relation to fishing grounds. The oldest respondents said that, whereas they had once not gone a long way to fill their nets, they now needed to sail far out to sea for a reasonable catch. Among the youngest, no one had any idea that it had once been possible to fish off the coast, so no one thought of such areas as overfished. In their frame of reference, there were no fish in coastal waters.

In the 1930s, travel guides would recommend the Gulf of California to anglers for its wonderful and easy-to-catch goliath grouper. Today the oldest fishermen can remember catching as many as twenty-five a day some fifty or sixty years ago; by the 1960s the number was down to ten or twelve a day, and by the 1990s to one at the most. Whereas nearly everyone in the oldest and the middle group had caught goliath groupers, less than half of the youngest had ever set eyes on one. Especially amazing is that only 10 per cent of the youngest thought that the stocks of this fish had disappeared; most thought there had never been any in the first place.7 Similarly, the size of the largest fish ever caught became smaller and smaller as the age of the respondent declined.

The authors of the study concluded that these rapid changes in the perception of the environment (the ‘shifting baseline’) explain why most people are fairly laid back about the decline in biodiversity.8 This is naturally a depressing finding for ecologists, since it also means that it is an uphill struggle to make the public aware of the need for stock protection, which, from a scientific point of view, has become an urgent necessity.

In terms of social psychology, the study offers an excellent example of the fact that people’s evaluations change together with changes in their environment. It is like when two trains run on parallel tracks and seem motionless in relation to each other. Shifting baselines naturally have implications for how people perceive and evaluate threats or losses, and hence for what they regard as normal and abnormal.

Shifting baselines do not concern only the biological domain. Indeed, it may be easier to describe them in the context of social processes. If we think back to the uproar in the early 1980s over the plan to hold a census in Germany (when people denounced the drift to a ‘total surveillance state’ or ‘the baring of every detail of our lives’), and if we compare that with today’s carefree attitude to credit cards, mobile telephones, internet connections, and so on, then we find ourselves with a perfect example of shifting baselines in the sphere of the social. Every user of these technologies leaves electronic traces of his or her activity that can be reconstructed at any time, and the whole concept of a private life has radically changed. Yet scarcely anyone seems to feel that this restricts or ‘bares’ their personal life, probably because it does not involve a deliberate heightening of ‘transparency’ but is a collateral effect of innovations in which data protection or personal rights appear on the surface to be of little or no significance. The technology increases the ease of communication but at the same time leads to considerable normative changes, although, because of the shifting baseline, this is not really noticed.

Shifting social baselines may also feature in the acceptance of legislative changes – for example, those relating to Bundeswehr intervention abroad. This may make itself felt in a sense that such measures require less discussion, or even none at all. In the ecological sphere, increased environmental protection and higher energy costs have led in the last few decades to more fuel-efficient car engines, while at the same time a greater emphasis on safety and status has tended to make vehicles larger and heavier. The result has been a continual rise in cylinder capacity and engine performance, which largely eats up or even reverses the efficiency gains.

Shifting baselines are also a factor in the norms and beliefs, therefore the reference frameworks, which provide the bearings for what is true or false, good or bad.

REFERENCE FRAMEWORKS AND THE STRUCTURE OF IGNORANCE

On 2 August 1914, Franz Kafka wrote in his diary in Prague: ‘Germany has declared war on Russia. Swimming class in the afternoon.’ This is only a particularly striking example of how events that posterity learns to regard as historic are seldom experienced as such at the time. If they come to people’s knowledge at all, it is as one among countless other incidents in everyday life that take up their attention, so that even an exceptionally intelligent individual may find an outbreak of war no more worthy of note than his attendance at a swimming class. So, when does a social catastrophe actually begin?

At the moment when history is taking place, what people experience is ‘the present day’. Events acquire their importance only subsequently, when they have produced lasting consequences or, as Arnold Gehlen put it, have proved to be Konsequenzerstmaligkeiten – original events with profound consequences for everything that follows. This creates a methodological problem if we ask what people actually perceived or knew about the dawning event, or what they could have perceived and known. For original events usually escape perception, precisely because they are unprecedented; people try to insert what is happening into their available reference framework, even though its novelty means that it can only be a reference itself for later comparable events.

This is the very reason why German Jews did not grasp the scale of the exclusion process to which they would fall victim. In its first five years, many saw the Third Reich as a short-lived phenomenon ‘that one had to live through, or a setback to which one had to adjust, or at worst the threat of a narrowing life that was nevertheless more bearable than the uncertainties of exile’.9 The bitter irony is that, although the Jews’ reference framework certainly included painful historical experiences of anti-Semitism, persecution and robbery, this itself made it impossible for them to see that what was happening was something different, something utterly murderous.

Thus, what people can know depends first of all on what they perceive. But this is not the only reason why it is so difficult to investigate what people did or did not know at an earlier point in time. Since history is perceived from shifting baselines, it is a slow process for human perception, which only concepts such as ‘collapse of civilization’ later crystallize into a sudden event – once the far-reaching consequences are known. To interpret what people saw of a process that only later turned to catastrophe is therefore an extremely tricky business, apart from anything else because they, unlike we, could not possibly have known how things would develop. In looking from the end of a history at its beginning, we have to suspend our historical knowledge, as it were, in order to grasp what people actually knew at the time. Norbert Elias was not wrong in saying that one of the hardest tasks in social science is to reconstruct the structure of ignorance in an earlier period.10

Conversely, those living at the time of an event know nothing of how a future observer will see what is today’s present and tomorrow’s history. The paradoxical task, then, is to gauge what was not visible in contemporary conditions yet played a decisive role in shaping the future. There is only one source on which such a heuristics of the future can base itself: the past.

KNOWING AND NOT-KNOWING ABOUT THE HOLOCAUST

You know, the horror we felt at first – that a human being could treat another human being like that – somehow abated.

That’s how it is, no? And I saw in myself that we really became quite cool about it, as they say today.

Former prisoner in Gusen concentration camp

Every genocidal process begins at a point when no one has murder in mind, but when a majority of the population feels a perceived problem. On the other hand, it is hard to identify the moment when analysis of a social cataclysm like the Holocaust got under way, although this exerts a major influence on one’s findings. In any case, analysis of the Holocaust cannot begin when the event itself began, especially if the starting point is itself doubtful. Was it the so-called Kristallnacht of 9–10 November 1938? The introduction of the Race Laws in 1935? The victory of the Nazi Party in the elections of 1933? The enabling law of 1933 that gave it full powers? The introduction of forcible ‘euthanasia’ in 1939? The onslaught on Poland in September 1939? The first systematic ‘Jewish operations’, the mass shootings of summer 1941? Or the moment when Rudolf Höss, the commandant of Auschwitz, having been introduced to the effects of Zyklon B, thought himself lucky that mass murder could now proceed without undue bloodshed?

As we see, the historian’s beloved search for ‘starting points’ in a causal chain must end in failure. Causality is not a category that applies to social relations; contexts of interdependence may involve striking tensions and concentrated processes of change, but nothing like a decisive cause to which all else can be traced back. Thus, for example, the quest for a Führer Directive ordering the murder of the Jews is beside the point; a social process such as the Holocaust has a dynamic towards results and solutions that no one reckoned with, probably not even the ‘Führer’ himself. Social developments refer to changes in the figurative connections that people forge with one another, not to someone’s saying B because he has said A. Social processes – as in the case of ‘body counts’, which we considered earlier – therefore often lead to results that no single participant intended, but which do shape reality. It is true that the consequences of yesterday’s action are conditions for today’s action – but the reverse is not true. One cannot always infer back from the consequences to the preconditions, and never to the underlying ideas and intentions.

Nevertheless, the social reality of the ‘Third Reich’ is usually seen through the prism of the Holocaust, and there everyday life looks peculiarly static and hermetic. But the genocide was only the end result of an immensely accelerated eight-year process of social transformation. As we now know, support for the system grew continually from 1933 until the invasion of the Soviet Union. We are therefore talking of a normative ‘shifting baseline’: most citizens would have thought it unthinkable in 1933 that just a few years later, with their own active involvement, the Jews would not only be robbed of their rights and property but shipped off en masse to be murdered. These same citizens saw the deportation trains begin to leave in 1941; quite a few bought ‘Aryanized’ kitchen furnishings or living-room suites; and some thought it perfectly normal to run businesses or live in homes that had been confiscated from their Jewish owners.

All stages in the exclusion of German Jews took place in public. From the day of the Nazi takeover, a fundamental change in values made it seem increasingly normal that different standards of human interaction, and therefore of legislation and judicial process, should apply to human groups that were essentially different from each other.11 To reconstruct this axiological ‘shifting baseline’, we can draw on contemporary sources on everyday life such as the notes of Sebastian Haffner, the journals of Victor Klemperer or Willy Cohn, and the letters of Lilly Jahn. These show how, in a startlingly short space of time, the Jews and other human groups were radically excluded from the binding social norms of justice, empathy or love of one’s neighbour that still operated in the rest of society. It is often overlooked in analyses of the Third Reich that, although it was an unjust and arbitrary system, the arbitrariness and injustice were directed almost exclusively at those who ‘did not belong’; members of the Volksgemeinschaft continued as before to enjoy legal security and state protection in large areas of society.

A survey of 3,000 individuals, conducted in the 1990s, showed that nearly three-quarters of those born before 1928 knew no one who had been arrested or interrogated for political reasons during the Nazi period.12 Even more respondents stated that they had never felt personally threatened, despite the fact that, in the same survey, a large number said they had listened to illegal radio broadcasts, joked about Hitler or expressed criticism of the Nazis.13 Another remarkable result was that between a third and more than a half of respondents confessed to having believed in National Socialism, admired Hitler or shared Nazi ideals.14 A survey conducted in 1985 by the Allensbach polling organization produced similar findings. Of the respondents, who had to have been aged at least fifteen in 1945, 58 per cent confessed to having believed in National Socialism, 50 per cent thought that it had embodied their ideals, and 41 per cent had admired the Führer.15

This perceived lack of personal threat or repression rested on a strong sense of belonging, the other side of which was the daily demonstration that other groups, especially the Jews, did not belong. Immediately after 30 January 1933, the exclusion of Jews began to gather enormous momentum without meeting significant resistance from the majority of the population – although some might turn up their noses at the ‘SA or Nazi rabble’ or feel that the cascade of anti-Jewish measures was uncouth, improper, exaggerated or simply inhumane. Saul Friedländer gives an idea of what I mean by this ‘enormous momentum’:

The city of Cologne forbade the use of municipal sports facilities to Jews in March 1933. Beginning April 3 requests by Jews in Prussia for name changes were to be submitted to the Justice Ministry, ‘to prevent the covering up of origins’. On April 4 the German Boxing Association excluded all Jewish boxers. On April 8 all Jewish teaching assistants at universities in the state of Baden were to be expelled immediately. On April 18 the party district chief (Gauleiter) of Westphalia decided that a Jew would be allowed to leave prison only if the two persons who had submitted the request for bail … were ready to take his place in prison. On April 19 the use of Yiddish was forbidden in cattle markets in Baden. On April 24 the use of Jewish names for spelling purposes in telephone communications was forbidden. On May 8 the mayor of Zweibrücken prohibited Jews from leasing places in the next annual town market. On May 13 the change of Jewish to non-Jewish names was forbidden. On May 24 the full Aryanization of the German gymnastics organization was ordered, with full Aryan descent of all four grandparents stipulated.16

Such measures, which affected others but were naturally not unknown to the rest of the population, were an everyday phenomenon in the Third Reich. Scarcely a day passed without one more being added. The keynote was the ‘Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service’ (7 April 1933), which provided inter alia for the retirement of all non-Aryan officials. In the same year 1,200 Jewish professors and lecturers were dismissed, without a single protest from any of the faculties concerned. On 22 April non-Aryan doctors were excluded from the health insurance schemes that oversaw public healthcare.17 On 14 July 1933 the Law for the Prevention of Genetically Diseased Offspring was passed.

However the various measures appeared to individuals in the ‘Volk community’, it should be noted that even in these early stages – which implied a considerable value change in relations between people – there was little or no expression of discontent. As things got worse for some, others felt so much the better. It was a radically changed existential situation, which registered at the level of perception and reflection for the better-off, but did not seem at all radical – a normative shifting baseline. Not for nothing do people who were alive at the time still largely agree that the Third Reich was a ‘wonderful period’, at least until the invasion of the Soviet Union; some think it remained that until even later in the war.18 In this ‘shifted’ normative universe, even the deportation of erstwhile fellow humans to places about which nothing was known appeared part of normality.

A little thought experiment will make the scale of the value change clearer. If the deportations had begun in February 1933, immediately after the Nazi takeover, the deviation from what the majority considered within the bounds of normality would have been too great to have proceeded without friction. It would even have exceeded most people’s capacity to imagine it (quite apart from the fact that the Nazis themselves had not yet thought through the sequence that led from exclusion through deprivation of rights and property to deportation and annihilation). Only eight years later, that way of treating others was already part of what people had come to expect; it therefore did not strike them as out of the ordinary. As we see, a shift in fundamental social baselines did not require even a generational changeover or decades of evolution; a few years were enough.

And the participants did not notice how their perceptions of reality and their conceptions of what was right and wrong, social and antisocial, were changing. In view of this phenomenon of shifting baselines, we should not delude ourselves that moral convictions will make people pause at any point in an anti-human process and take a better direction. This is true not only of the Nazi period but also of quite different problems and situations.

SHIFTING BASELINES ELSEWHERE

People can find meaning in actions which, from the outside, seem incomprehensible, unspeakably cruel, sometimes even self-damaging or self-destructive. The example of Islamist suicide bombers shows that it can even make sense to blow oneself up and kill as many others as possible. Of course the decision to do this is not taken alone: it is embedded in a social frame of reference and is preceded by a shifting of baselines. For suicide bombing is a normative innovation within the history of Islamic fundamentalism, and even the bombers’ families would have thought it inconceivable a few decades earlier that they would feel joy at their son’s or daughter’s action. The Koran forbids the taking of one’s own life.

Once again a value shift made it possible, within quite a brief space of time, to regard a person’s readiness to blow themselves up as highly positive and desirable. In his work on terrorism, Bruce Hoffman has investigated the religious coding of political acts of violence and the role played by the traditional posture of the ‘martyr’. ‘The images of suicide terrorists emblazoned on murals and wall posters, calendars and key chains, postcards and pennants throughout Palestine are but one manifestation of this deliberate process’, whereby social value is attached to self-destruction. ‘Similarly, the suddenly elevated and now highly respected status accorded their families is another. The proud parents of Palestinian martyrs, for instance, publish announcements of their progeny’s accomplishments in local newspapers not on the obituaries page but in the section announcing weddings.’19

Modern media play an important role in this value change – for example, when Palestinian television carries publicity that urges young people to sign up for terrorist organizations.

One such segment broadcast in 2003 depicts the image of a young Palestinian couple out for a walk when suddenly IDF [Israeli] troops open fire, shooting the woman in the back and killing her. When visiting her grave, her boyfriend is also shot dead by the IDF. He then is shown ascending to heaven, where he is welcomed by his girlfriend, who is seen dancing with dozens of other female martyrs, portraying the seventy-two virgins – the promised ‘Maidens of Paradise’ – who reputedly await the male martyr in heaven.20

Evidently such broadcasts are closely linked to suicide attacks that take place shortly afterwards. (A reader who feels haughtily superior about such actions would do well to pause and ask himself whether it makes more sense to die for a ‘Leader’, without any prospect of reward in the afterlife.)

The families of suicide bombers receive financial support (sometimes as much as $25,000 per family member killed), in addition to things such as television sets, furniture or jewellery. Terrorist organizations or their funders also help to supply infrastructure that the local state does not provide – for example, healthcare, education and social welfare. All terrorist organizations gain recruits as a result of the loyalty that such forms of practical aid generates, but in the process they weed out those who seem to represent false values or who merely care about other people’s problems. This is as true of Hamas as it is of the IRA or ETA. Ideology plays scarcely any role in this practical transformation of social space. People change their values because their world changes, not vice versa.

Video messages that suicide terrorists recorded before their mission provide further information about the value shift in Palestinian society, which means that, according to survey evidence, more than 70 per cent of Palestinians approve of suicide attacks.21

As norms have changed within Islamic fundamentalism, establishing forms of violence unthinkable two decades ago, social norms have also changed in another part of the configuration: that is, among those on the receiving end of suicide attacks. This concerns the value of freedom relative to security, the willingness to put up with manifold forms of restriction and surveillance and to support military intervention abroad.

Changes in one part of the societal field of tension set up pressure to change in quite different parts of the field. This feedback mechanism is particularly evident in the case of terrorism, where actions on one side generate pressure on the other side. Thus, any successful attack not only kills random victims but, as a communicative act, shakes the sense of security of countless other people. The shifting baselines are then almost complementary: every terrorist attack generates a need for greater security among its potential targets and makes them more willing to restrict their own freedom in return for at least a sense of security.

In Germany, following the 9/11 attacks in New York, anti-terror legislation valid for a five-year period provided for a number of adjustments to existing laws (on defence of the constitution, police powers, security vetting, passport and identity card regulations, air traffic control, the central criminal register, energy security), so that the security forces would have the means to improve their exchange of information, surveillance operations, border control, and so on. In particular:

- – The internal intelligence agency (Verfassungsschutz) may gather information about money transfers and bank accounts of suspicious organizations and about individuals in banks and finance companies. It also has powers to monitor air transport companies and telecommunications operators and service providers.

- – The Federal Criminal Police Department (Bundeskriminalamt) received greater powers to investigate computer sabotage, including on grounds of ‘initial suspicion’.

- – The federal police were given powers to deploy security agents on board aircraft and to carry out wider checks on individuals.

- – New provisions were introduced to deny a visa or residence permit to individuals who endanger the security of the Federal Republic, take part in acts of violence, publicly call for the use of violence or belong to a terrorist association. Identity and residence papers were further protected against falsification.

- – In the context of asylum procedures, powers were created to record applicants’ voices as a way of determining their country of origin. Identity materials (e.g., fingerprints) would be kept for ten years after the decision on asylum, and data could be passed on to the Bundeskriminalamt.

- – The Register of Aliens law permitted better checks on incoming traffic. Police access to the register was supposed to flag immediately whether someone was residing in Germany legally. The data could be accessed online and not, as before, released only on postal application to the central register.

- – As regards passports and identity papers, provision was made for computer-supported identification of individuals (photograph, signature and biometric features).

Germany’s anti-terror legislation was reviewed in 2005, and supplementary provision was made for the Verfassungsschutz to gather information about activities not previously considered anti-constitutional. It may now also require airlines to provide information about flight bookings by suspicious individuals.

However, in a ruling on 31 January 2007 (StB 18/06) the Federal Court prohibited the kind of secret online searches that the security services and the interior minister had been urgently requesting. Until then Trojans and backdoor programmes had been used under §102 of the Code of Criminal Procedure to conduct searches without the target’s knowledge where there was suspicion of a serious criminal offence. But the Federal Court based its decision on the fact that computers are also part of the sphere of private life (in which searches must be carried out in the presence of suspects or witnesses). At the time of writing, however, the interior ministry is apparently ready to deploy new spyware, in the shape of mini-programmes that can trawl through a user’s hard disk and search for data movement pointing to the preparation of a terrorist attack.

A new anti-terror database, for which the go-ahead was given in December 2006, makes it possible to link IT systems to intelligence agencies, security forces and the police. This contains information about individuals under suspicion (membership of terrorist associations, possession of weapons, telecommunications data, bank accounts, education and occupation, family status and religion, place of residence and journeys abroad), as well as reported losses of identity papers. Of course not only terror suspects but all kinds of other people are in danger of ending up in this database.

In September 2007 a ‘Forum for Collaboration between Security Authorities and Industry’ was created in Brussels. According to a report of its meeting, ‘the European Union will release a total of €2.135 billion by 2013 for the development of new security technologies, which are intended to give member states far-reaching possibilities of surveillance and investigation.’22 Two aims will be the development of devices that can detect explosives in private homes and video cameras that can detect unusual movements in a crowd. Even the vice-president of the European Commission, Günter Verheugen, described these as technologies ‘which are fundamentally changing our societies’.23 The newly founded forum is, moreover, independent of the European Union.

Most other European countries have made similar moves in security legislation and technology: a million surveillance cameras were due to be deployed in France by 2009,24 and their ubiquitous presence is already a fact of life in Britain. In the United States, as we have seen, a special ministry was created for ‘homeland security’ after the 9/11 attacks. All the related watering-down of data protection and computer privacy seems to have raised scarcely any objections – on the contrary, the new laws and technologies find wide public support, especially after a terrorist attack has taken place or been foiled. Opinion surveys in Germany point to a growing fear of terrorism,25 whose place on the scale of perceived threats has risen considerably in relation to classical issues such as epidemics, accidents or unemployment.26

There is also a new level of support for tighter security policies. Whereas in 2005 only 37 per cent of the German public thought that ‘more needs to be done against the terrorist threat’, the figure had risen to 46 per cent a year later. More than two-thirds of Germans approve of greater video surveillance at railway stations, for example;27 and 65 per cent thought in 2007 that not enough was being done in the fight against crime.28

One interesting point is that two-thirds of survey respondents do not consider that anti-terror measures involve a restriction of civil liberties.29 A European Commission study showed that, in general, only people over forty-five feared that data protection was inadequate, whereas the under thirties saw no problem in the existing state of things.30

Such findings indicate that baselines are shifting on the other side too. In the event of a further rise in the perceived terrorist threat (following another major attack, for example), the priority may shift still further from freedom to security – not without reason, since only the living are in a position to enjoy freedom. Demands for the protection of personal liberties have clearly weakened in comparison with the 1970s and 1980s, and survey results are already evidence that citizens will not only condone but demand stronger security measures in the future. So, values and standards of normality are shifting within democratic societies.

How will conceptions of a normal and measured response to external threats change if growing numbers of environmental refugees pose security problems at state frontiers? How will the trade-off between freedom and security develop if terrorist attacks become more frequent and more violent? What calls for orientation and stability will appear if a catastrophe hits European cities? There is much historical evidence that unsatisfied expectations of stability and security lead to outbreaks of violence, and that a sense of increased population pressure can turn against refugees or others who are held responsible for it. The willingness to exchange freedoms for security also requires no further demonstration. Faith in stable values and standards of normality and civilized behaviour therefore seems unwarranted. Radical consequences of climate change may bring a radical value shift in their wake.

Real or perceived threats from outside generate a deeper sense of internal belonging; the terrorist threat is thus conducive to the strengthening of we-group identity,31 which in turn involves establishing who ‘the others’ are. Thus, threat–reaction configurations increase the need for ‘we’ and ‘they’ identification; it then depends on the scale of the perceived threat whether reactions of an excluding or aggressive kind are directed against members of ‘they-groups’. As Mary Kaldor puts it, identity politics gains a new importance in the age of globalization.

To sum up: a change of values in one part of the transnational field of tension does not leave untouched the values which are added in another part – yet people in both parts remain convinced that they are adhering to values they have always upheld.