11

WHAT CAN AND CANNOT BE DONE — 1

Whether radical solutions to social problems will be blocked in the future will be another test of how much societies have learned from their history. This is not an academic but a political question.

To be sure, political theory in the age of global danger cannot concentrate on models for the future, not only because the imagination for that is lacking, but also because the utopian social promises of the twentieth century turned out to be totalitarian nightmares. On the other hand, that is precisely why a revival of political theory is necessary, and why it must prove its worth in a critique of any limitation of survival conditions for others. It also needs to be considerably more future-oriented than it has been in recent decades. Societies with no experience of the huge dangers ahead are like an oil tanker steaming towards an iceberg, no longer able to avoid it although it has long been in their field of vision.

After all that has been said about the social consequences of climate change, it should not be hard to imagine that the world will look markedly different in a few decades from now. Indeed, it is to be feared that in quite a few regions the conditions for human life will have considerably worsened. The question that suggests itself is therefore: What can be done for the author of this book to be proved wrong?

GOING ON AS USUAL

One option is as simple as it is obvious: to go on as usual. This would mean a continuation of economic growth, requiring further imports of fossil fuels and other raw materials and systematically reducing the medium-term capacity to help or support societies that fall into major difficulties. Such a strategy accepts, for example, that car fuel will have to contain an increasing bio-element, in order to extend the time before oil reserves run out. But this implies in turn that rainforests will have to be destroyed, so that land can be cleared for oil-bearing plants to provide the biofuel. This is already happening in many countries in Asia and South America;1 and it often goes together with forcible land expropriation and the expulsion of local people.

To go on as usual means a policy of securing supplies through agreements with countries that neither respect human rights nor observe environmental standards. It must also accept that the means for humanitarian intervention in crises will be more limited than they are today, because the number of conflicts and the flow of refugees will increase and the sources of livelihood will diminish.

Aid will therefore have to be more targeted; some countries and regions will have to be excluded from it. Negative developments of this kind will unfold not in the public spotlight but in backstage departments that contain no potential for scandal and raise no obstacles to action. Such a strategy may thus seem rational, until the painful consequences of climate change spread to initially unaffected regions – either directly or in the form of economic shockwaves from other countries’ wars and conflicts, terrorism or migration pressure; or else in the form of social conflict between new generations who have no chances in life and older generations responsible for the effects of past pollution who did enjoy many opportunities. Nevertheless, things might go on for a few more decades, during which ‘business as usual’ might seem the most rational strategy to today’s middle-aged, the core group of the functional elites.

Another reason why this seems a neat solution is that it raises no obvious ethical problems. For the nation-state is a player that acts on behalf of others not as an individual, and in relations between states such categories as egoism, inconsiderateness or indolence are irrelevant. Any state can play dirty, but that does not change by one iota its bargaining power in the international arena.

If one were to imagine the ‘go on as usual’ strategy at the level of individuals, one would immediately think of a sociopath who has no problem consuming seventy times more than anyone else2 while largely relying on their raw materials – or someone who uses fifteen times more energy, water and food than the less well-off and discharges nine times more pollutants into the atmosphere. Such a personality would also be totally unconcerned about the lives of his children and grandchildren, accepting that, because of him and his kind, 852 million people worldwide go hungry and more than 20 million are refugees.

All normative criteria would classify such a person as a social misfit or, more bluntly, a dangerous parasite, whose game should be put a stop to sooner rather than later. But collective players escape such moral attributions because in this case they are simply representatives of states, institutions, associations or corporations, who shape action structures from which they can distance themselves subjectively at any moment;3 immorality is simply not an issue in international politics. This is why a category such as ‘failed state’ – which Washington introduced to bolster its use of ‘pre-emptive strikes’ – sounds so out of place: so long as one is not dealing with personal attributes, morality is of no relevance to action. Individuals can think of themselves as acting morally even if the community they help to shape behaves ‘immorally’.

This makes the inequalities and injustices of the globalized world appear nondescript and unexceptional, so that someone who feels responsible for the poverty of people at the other end of a chain that he and others like him originated cuts an irrational figure in the eyes of the West. For this reason, it is extremely unlikely that a strategy other than ‘business as usual’ will be chosen in the lands of affluence.

Someone who, in the name of species survival or justice between generations, finds this an unacceptable solution has three possible (and not mutually exclusive) ways of trying to change things for the better. The first and most popular is to individualize the problem and the solutions. A recent book on climate change, for example, offered a hundred tips on how to save the world, which ranged from educating children in environmental protection (tip 10) through using one’s dishwasher only when it is full (tip 35) to forming car-sharing clubs (tip 56) and separating refuse for recycling (tip 95).4

Such tips not only fall grotesquely short of the scale of the problem but, by individualizing it, grossly understate the level and complexity of the responsibilities and obligations in relation to climate change. The false, but highly attractive, assumption that social changes begin with the little things in life becomes ideological if it frees corporate or political players of their obligations, and irresponsible if it claims that the problems associated with climate change can be tackled at the level of individual behaviour. When the oil industry flares off 150 to 170 billion cubic metres of natural gas every year5 – as much as the industrial countries Germany and Italy combined – the savings made by individual households become little more than a footnote.6 It is certainly true that the cleanest energy is that which is never used, but this has little relevance in a global context of pollution and resource consumption in the growth-oriented newly industrializing countries. On the other hand, the psychological effect of the emphasis on individuals is all the greater, since it suggests that it is within their power to effect a solution. We can all do our bit, it seems, even when we next switch on our dishwasher.

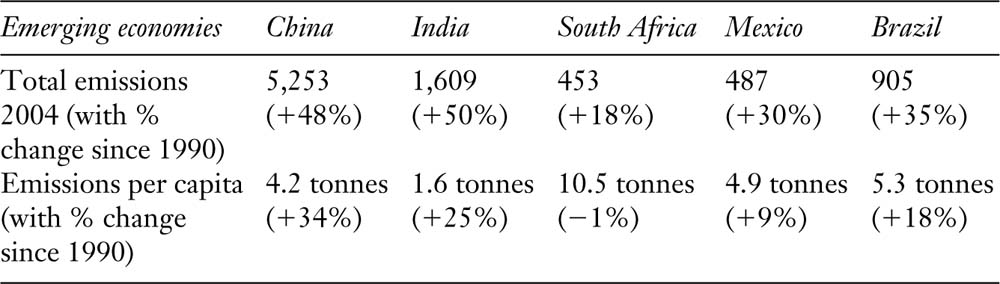

Table 11.1 Emissions of emerging economies (in millions of tonnes)

Source: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung: M 02.07 CO2-Emissionen Schwellenländer (www.bpb.de/popup/popup_grafstat.html?url_guid=7825TW).

The second level of action concerns the initiatives taken by various states since the IPCC reports – from the climate protection programme of the German environment ministry to the Australian proposal to replace all conventional light bulbs with low-energy ones. Measures such as home insulation undoubtedly lead to energy savings, and the German government’s target of a 40 per cent cut in CO2 emissions by 2020 is ambitious but certainly on the right track. Even if international disparities in climate policy, and the fact that emissions do not stop at frontiers, limit the effect of national solutions, such moves by individual collective players are certainly helpful. Innovative strategies change the configuration that societies create together, at least gradually, and the role of the pioneer may be inspirational. Here too the psychological effect is considerable: the feeling that nothing anyone does can make a difference is reduced. On the other hand, one should not lose sight of the limits built into such strategies. National solutions cannot ‘turn the climate round’, because their quantitative impact remains too exiguous.

It is at the international level that the complexity is greatest and the loss of control most evident. There is no supranational organization that can order sovereign states to emit lower amounts of greenhouse gases than they think reasonable. The same is true of river pollution, dam construction or deforestation. Nor is there an international monopoly of force that can sanction individual countries – for example, in relation to population resettlement or expulsions, land confiscation or human rights violations accompanying a ruthless environmental policy. A division of powers certainly exists within states, but not between them; only international criminal law offers the first rudiments of supranational regulation, with the possibility of putting on trial individuals responsible for massacres or genocidal acts.7 A major development of supranational institutions, especially of ones with real teeth, is still a long way off and currently has no effect on the problem of global warming. It may be hoped that the problem will give a further impetus to the creation of such institutions; international criminal law has its roots in the social disaster of the Nazi crimes, which the Nuremberg trials defined as ‘crimes against humanity’. But at present international agreements on environmental questions are limited to self-imposed obligations, and any failure to meet these does not make a country liable to sanctions. Here too, then, the upshot is that everything is good which serves climate protection at international level, but it is an illusion to believe that emissions can be cut sufficiently by 2020 to contain global warming.

These are the levels of social action available in the current state of play. It must therefore be assumed that the problem of climate change is unsolvable – which means that the earth will warm by more than the extra 2 degrees that are still considered manageable.

FUTURE PASTS

For a long while I stood on the bridge that leads to the former research establishment. Far behind me to the west, scarcely to be discerned, were the gentle slopes of the inhabited land; to the north and south, in flashes of silver, gleamed the muddy bed of a dead arm of the river, through which now, at low tide, only a meagre trickle ran; and ahead lay nothing but destruction. From a distance, the concrete shells, shored up with stones, in which for most of my lifetime hundreds of boffins had been at work devising new weapons systems, looked (probably because of their odd conical shape) like the tumuli in which the mighty and powerful were buried in prehistoric times with all their tools and utensils, silver and gold. My sense of being on ground intended for purposes transcending the profane was heightened by a number of buildings that resembled temples or pagodas, which seemed quite out of place in these military installations. But the closer I came to these ruins, the more any notion of a mysterious isle of the dead receded, and the more I imagined myself amidst the remains of our own civilization after its extinction in some future catastrophe. To me too, as for some latter-day stranger ignorant of the nature of our society wandering about among heaps of scrap metal and defunct machinery, the beings who had once lived and worked here were an enigma, as was the purpose of the primitive contraptions and fittings inside the bunkers, the iron rails under the ceilings, the hooks on the still partially tiled walls, the showerheads the size of plates, the ramps and the soakways.8

W. G. Sebald’s ghostly impressions, as he visits a former military establishment on the Suffolk coast, involve a curious telescoping of his own times. Something similar may be felt at the remnants of the vast underground site for V-2 rocket production at the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp, or at certain abandoned locations in Eastern Europe. What one sees there are infrastructures built with a huge input of energy and often at the cost of thousands of human lives. At Mittelbau-Dora the construction work had to be done so quickly that many a labourer, having been worked to death, was cemented without further ado into the lining of the tunnels; one can still find the corpses there today. In many cases, these vast projects that looked with such confidence towards the future lasted only a few years; they now stand as futile witnesses to bygone plans that can be decoded, if at all, only with difficulty. Sometimes, historians or archaeologists look in vain for a meaning that is simply not there.

Sebald’s monuments at Orford Ness, like the Nazi factories for the production of aircraft, rockets and dead bodies, are peculiar islands of time in an advancing present, relics of a past future. Just as the military research establishments worked on future wars, the aim of Mittelbau-Dora was to prepare the way for Nazi world domination. And the fallow lands of communism testify to dreams of a future in which the new man would have come of age. Its rusty ruins, grown over and serving no purpose, harbour not only the past but also a future that never became reality.

Human beings live in the present, but mentally they can also travel through time into the past and the future. Man’s distinctive capacity to situate personal existence in a space–time continuum, looking back at a past that preceded the present, serves the purpose of giving the bearings for future action. It is also possible to look ahead to the future. The grammatical form for this is the future perfect (‘will have been’); its mental form is what Alfred Schütz called ‘anticipatory retrospection’.9 This plays a central role in human behaviour: any outline, plan, projection or model involves looking ahead to a state of affairs that will one day have come to pass. Human motives and energy feed off such anticipation – from the desire to reach a state that is different from the one existing today.

This fascinating capacity has given human beings the evolutionary advantage of being able to play through beforehand any actions that will change the shape of the world, and to weigh up their various pluses and minuses. More generally, it has endowed them with a mind that draws energy not only from what is given but also from what is desired and dreamed.

This involves a certain dialectic, of course, and anticipatory retrospection in the style of Hitler or Speer10 – whose utopian self-assurance produced the grandiose plans for a rebuilt capital, Germania, complete with a museum of the extinct Jewish race11 – represents the dark side of futuristic certainties, as well as of all totalitarian variants associated with the Marxist utopia of an emancipated society. But it is precisely horrific cases such as National Socialism which demonstrate the mental energies that the promise of a seemingly attainable future can release, provided that everyone goes along with it. This ‘feel good dictatorship’12 not only brought out the vast destructive energy that would eventually leave behind 50 million dead and a half-destroyed Europe, but also enlisted feverish support for a societal project that promised a rosy future to everyone who belonged – until late in the war, that is, ‘when the vanguard of the Sixth Army had reached the Volga and not a few were dreaming of settling down there after the war on an estate in the cherry orchards beside the quiet Don’.13

Anticipatory retrospection regularly becomes deadly if its initiators seek to shape the whole world in its image. For every social utopia inevitably presupposes a view of what man is: the error of utopianism, argues Hans Jonas, is its conception of the ‘human essence’.14 If there is such a thing as the human essence, then it lies in plurality and its constitutive potential – its cooperative way of life and its capacity to anticipate future opportunities and threats. And this openness to potentiality is all the greater, the better the conditions of life are in the present: only the freedom of a secure livelihood permits the luxury of exploring the possibilities for a better existence; and, conversely, that luxury can be curtailed at any time, or even vanish without trace, if existential security comes under threat.

This implies that the scope for developing one’s potential, the availability of future opportunities, is highly unevenly distributed. But, for a society that places itself culturally and politically within the Enlightenment tradition (including all its postmodern and post-postmodern variants), such inequality is not acceptable. It means that another approach must be found to the problem of climate change, not only for the sake of one’s livelihood but also for the sake of one’s identity. What we are talking about, then, is social self-presentation.

THE GOOD SOCIETY

Global warming has come about because of the thoughtless use of technology, so any attempt to fix things through more and ‘better’ technology is part of the problem, not of the solution. Since the qualitative and quantitative scale of the problem is such that no one knows what a rescue strategy would be like, it is necessary to get away from a ‘business as usual’ mind set. To rise above responses to immediate stimuli and pressures is precisely what makes human existence unique and purposive action possible. In principle, then, new mental horizons are necessary to find a way out of crises. Overhasty thinking can prove fatal; the perception of a huge problem should give pause for thought, in which mental space can open up to determine what is involved and what can be done about it. Only freedom from illusions makes it possible to escape the deadly force of circumstance, such as one sees in the false alternative of coal-fired stations or nuclear power as a response to climate change.

This is a false alternative, because the two energy technologies each rest upon limited resources and have proven to have unforeseeable consequences. The climate change debate is full of such traps. Another example is whether societies behind in modernization should be allowed the same pollution rights that early industrialized countries had in an age when no one gave a thought to such matters. In the present day, when the consequences of a heedless attitude are known, a question like that expresses nothing other than a kind of forced stupidity. There are definitely better contexts in which to consider the case for global justice than one of further limitations on the opportunities that human beings will have in the future. If there is to be debate about that, it should centre on fair distribution of the burdens attached to cuts in energy use; ethics commissions should work out proposals for the wealthy high-tech nations to provide less modernized countries with cost-free technology for the reduction or avoidance of noxious emissions – although even that begs the question as to whether it is desirable for everyone to achieve Western levels of modernization.15

Another false alternative is whether the growing numbers of environmental or climate refugees should be parked temporarily in third countries or left to drown in the sea. Here the ‘objective constraints’ show their totalitarian logic, and it should be made clear that such people are deported or perish because the Schengen countries have agreed that they do not want them. This is not a moral point but a simple statement of fact. If one feels no moral dissonance over policy decisions to treat other human beings in that way, one can happily continue to refuse them admission.

One way out of this dilemma would be to use one’s native wit, not for devising ostensibly more humane strategies of exclusion at considerable public cost, but to explore participatory avenues that the early industrialized countries will anyway have to embrace in the medium term for demographic reasons. Why should societies that are also planning for future challenges stick to the ideal of an ethnically homogeneous state, which will anyway prove antiquated in the face of further modernization requirements?

And if one is trying to move beyond false alternatives and ‘objective constraints’, one might do well to take a fresh look at climate change and define it as a cultural problem. This anyway seems obvious, because climate change affects human cultures and can be perceived only within the framework of cultural techniques such as agriculture, livestock breeding, fishing or science. Nature is essentially indifferent to ecological problems; they are a threat only to human cultures.

The forms and possibilities of future human life are therefore a cultural issue that relates to our own society and lifeworld. This raises a series of questions. Can a culture be successful in the long run if it systematically uses up resources? Can it survive if it accepts the systematic exclusion of future generations? Can such a culture be a model for those whom it must win over if it is to survive? Can it be rational if it is regarded from outside as exclusive and predatory and rejected for that reason?

The redefinition of climate as a cultural issue, together with a move away from the fateful, often deadly, logic of ‘objective constraints’, would offer an opportunity for qualitative development, especially if the situation is as crisis-prone as it is at present. A fixation on ostensibly objective constraints precludes ways of thinking and acting that a more detached view of things would immediately embrace.

Let us take four examples, each very different from the others.

Norway does not invest its oil revenues in prestigious infrastructural projects or the raising of living standards, but pursues a far-sighted strategy that will enable future generations to enjoy today’s high living standards and to benefit from the achievements of the social state. It therefore chooses ethical investment criteria, excluding, for example, companies involved in the production of nuclear weapons and favouring climate-friendly energy suppliers.16 The Utsira municipality on Rogaland, a North Sea island in the south of the country, is already self-sufficient in energy thanks to its combination of wind farms and hydro-installations. It has set an example in the sustainable use of national economic resources.

Switzerland opted twenty years ago for a public transport system which ensures that every local community is connected. Trams were reintroduced in Zurich at a time when they were disappearing from many German cities, and new stretches of railway were laid when services were closing down in many other countries. Switzerland today has the densest public transport network in the world, although its frequently mountainous terrain could scarcely be less favourable. ‘Post cars’ link up remote villages and side valleys. The average Swiss makes forty-seven train journeys a year, compared with the EU average of 14.7.17

Estonia guarantees cost-free internet access as a basic right. Blanket provision with communication facilities not only reduces bureaucracy and enhances the potential for direct forms of democracy; it has also become a key driving force of modernization, which appeals especially to younger members of society.

The decision of the German government in 2003 to remain outside the military alliance against Iraq, despite considerable external pressure, has proven to be correct and far-sighted. It avoided a mistake which, by reminding everyone of Germany’s negative historical role in the two world wars of the twentieth century, would have had unpredictable consequences for political life in the Federal Republic. This was a practical example of learning from history.

These four policy orientations, though relating to very different matters, had a common denominator in that they all touched on an aspect of identity. Each decision concerned not only a particular issue but the wider question of what the political community wanted to be: a society that was fair towards future generations (Norway); a society that offered all its citizens the same mobility (Switzerland); a republic with equal communication opportunities for all (Estonia); a society capable of learning from the past that held back from disastrous policies of military intervention (Germany). This identity level of the various decisions contained a statement about who people wanted to be (as a Norwegian, Swiss, Estonian or German) and the conditions under which they wanted to live, at least in the area to which the policy referred. It thus seems highly significant for a cultural approach to global warming. For the ‘what is to be done?’ question simply cannot be addressed unless an answer is first given to the question of how people want to live.

In fact, this question cannot not be answered. ‘Go on as usual’ is one possibility, pointing further down the road that led to the problems one is trying to solve. It would mean deepening the asymmetries, inequalities and injustices, between generations as well as countries, which climate change brings in its wake. And every answer rules out at least one other possibility.

How do people want to live in the society of which they are part? This is a cultural question: it forces us to discuss who counts as a member of society, what form participation should take, how material goods as well as immaterial ones such as income and education should be distributed, and so on. The setting of priorities – subsidies for fossil fuel use (coal-mining) or increased spending on education, job creation in backward industries or investment in education and training for new patterns of employment – involves answers that define the self-image of the community and whether citizens can identify with it. They are cultural issues, in which the guiding imperative is whether the potential for future development should be limited or not.

The premise for a participatory, open-structured model of society is, on the one hand, Western levels of material wealth and the international obligations that such wealth implies and, on the other hand, political thinking that goes beyond the immediate situation of the day. The world of global capitalism, devoid of orientation or transcendence, creates no sense of meaning within itself and is inadequate for such long-range purposes. What is needed, precisely in times of crisis, is to develop visions or at least ideas that have never been thought before. This may all sound naïve, but it is not really. Besides, what could be more naïve than to imagine that the train bringing destruction on a mass scale will change its speed and course if people inside it run in the opposite direction? As Albert Einstein said, problems cannot be solved with the thought patterns that led to them originally. It is necessary to change course, and for that the train must first be brought to a halt.

REPRESSIVE TOLERANCE

A serious approach to the problems of inequality and violence bound up with climate change would have to concern itself with such categories as justice and responsibility – that is, to argue in the light of value decisions and to replace cultivated indifference with a capacity for normative discrimination. This raises the question of which groups or individuals in global society are better placed than others to assert their interests. In 1965 Herbert Marcuse published a famous essay on ‘repressive tolerance’, which, however adventurous its drift seems today, accurately points out that ‘the function and value of tolerance depend on the equality prevalent in the society in which tolerance is practised’.18

Technically, tolerance is a variable dependent on the level of equality achieved within and between societies. Where tolerance is practised without reference to the existing power relations, it works in principle to the advantage of those with the greatest power. So, in a society based upon inequality, tolerance is fundamentally repressive because it normatively and ideologically entrenches the positions of those with the least power. In Marcuse’s time it was understood that his argument served to ground a kind of putative right of resistance (for third world liberation, for example), but, in relation to the findings set out in this book, ‘repressive tolerance’ might describe the lack of articulated counter-tendencies to the global asymmetry between rich and poor countries.

‘Repressive tolerance’ is also an appropriate term when the opportunities for people elsewhere or for future generations are restricted or even removed without arousing immediate criticism. Societies with a culture of repressive tolerance lack all possibility of critically examining themselves and moving towards a more desirable state of affairs, so that ideas about how the future should look seem reduced to the unhelpful formula: like now, only better. Such is the extent of the West’s vision today, although people have a strong sense that it is based on an illusion.

THE CAPACITY FOR A HISTORICAL NARRATIVE ABOUT ONESELF

Individualist strategies against climate change have a mainly sedative function. The level of international politics offers the prospect of change only in a distant future, and so cultural action is left with the middle level, the level of one’s own society, and the democratic issue of how people want to live in the future.

Cultural work at this level would not only create a sense of identity but also engage those who wish to make a much greater contribution as individuals to the control of emissions – for example, people in the energy supply or automobile industry. Internationally, moreover, the development of a different option would at least produce new interests, even if it was unable to influence a particular climate regime. It would have the psychological advantage that thinking would be less prone to illusions and more adequate to the nature of the problem, and this in turn might be another factor generating identity. The focus would be on citizens who do not settle for renunciation – fewer car journeys, more tram rides – but contribute culturally to changes that they consider to be good.

For some twenty years now, the view has been gaining ground in development policy that material aid does not produce the desired effects, and that a great deal depends upon the state structures, institutional functionality and legal system in the recipient country. Attention has therefore shifted to the concept of ‘good governance’, which requires the fulfilment of a number of criteria such as transparency, efficiency, participation, responsibility, market economics, the rule of law, democracy and justice. Indeed, since the 1990s development funds and other material support have been disbursed according to whether the state in question meets these criteria. It has been objected that this is an ideological approach, which insists too much upon a profile laid down in advance, and it might further be said that donor countries are assumed to fit the profile, whereas it is used as a test of rectitude for recipient countries.

We cannot here go further into the problems of this approach, but it does seem fruitful to ponder on what is involved in the idea of good governance. Similarly, one might develop criteria for a good society that reflect the concept of good governance. First of all, a good society would have to maintain its development potential at the highest possible level, which, given the past impact of industrialization on the environment, would also mean avoiding decisions that have irreversible consequences such as resource exhaustion or unfair burdens on future generations, as in the case of nuclear waste.

Decisions affecting social development in areas such as security, the legal system, education or welfare would also have to meet the criterion of reversibility, in order to ensure that society remains open-ended in its structure. A further yardstick of the good society is the opportunities it offers for participation, including immigration issues such as the right to asylum and the involvement of citizens in debates and decision-making on questions of importance for the future. With today’s dense networks of communication, it is by no means necessary that forms of participation should be geared to the electoral cycle. Estonian-style access to communication facilities as a basic right for all opens up the possibility of novel forms of extra-parliamentary debate and direct forms of democracy.

At the same time, greater opportunities for communication and participation would increase the extent to which citizens identify with the society they help to shape. As regards the climate problem and the proposed solutions on offer, the cultural project of the good society means turning away from the illusion that people would treat the world differently if they were told that it would one day be in less danger as a result. Such an argument does not work psychologically, because individuals cannot perceive the effects of their action on the environment and are left only with the experience of giving something up. The idea of the good society does not emphasize renunciation, but rather social involvement in achieving a better climate. And a society that encourages greater participation and commitment is better placed to solve urgent problems than one whose members remain indifferent.

The individual psychological equivalent of this concept of social involvement is ‘empowerment’, which refers to the strategy of highlighting the individual’s strengths and seeking to promote them. In this sense, the concept of the good society draws on the potential of its citizens, offers them greater participation, and makes better use of the resources of involvement and interest than traditional styles of politics do. In other words, such a society initiates a conscious strategy of reflexive modernization.19 In contrast to the first modernity of the past and the second modernity of the present, the good society would represent the third modernity: the future. It tells a new story about itself.

The crux of functional modernity is that it has no historical narrative in which people can describe themselves as citizens and, on that basis, develop the sense of a definite collective identity, a ‘we’. The good society, once created, would be able to tell such a story about itself.

Science has provided human beings with the ability to anticipate changes in their conditions of life even when these are not yet perceptible to them, and their intellectual capacities enable them to draw the appropriate conclusions. With the help of social and cultural skills, these conclusions can be translated into a changed practice. Thus, a practically oriented understanding that it is necessary to avert the worst consequences of global warming would mean that people demanded not only a radical worldwide reduction in resource use but also a whole new culture of participation; this still seems unthinkable today, but it must be urgently addressed if the outcome is to be at all different. In this perspective, ‘climate change’ would be the starting point for fundamental cultural change, in which the reduction of waste and violence was seen not as a loss but as a gain.