As Plato once said, “Necessity…the mother of invention.” In the case of Boeing, they needed to assemble a brand-new airplane, so they invented new tools and systems and configured a new production line in the largest building in the world by volume.

“There’s so much in the factory that has never been done before—because it’s an exciting airplane that’s never been done before,” says production engineering manager Todd Eilers. Eilers joined the 787 program in 2004 to head the factory design team.

The 787’s large composite structures have completely changed the way an airplane is put together. Traditional “monument” assembly tooling has been almost completely eliminated. Monument tools are fixed structures that include devices bolted to floors with heavy concrete bases. Getting rid of them is good for productivity, as they can impede the factory flow. Instead, portable tools, designed with ergonomics in mind, move the assemblies into place.

And, because the 787 comes together from large assemblies rather than many smaller pieces, the Dreamliner production line doesn’t need to move continuously. Boeing has had great success in building its 737 aircraft on a nose-to-tail moving line—it dramatically reduced the time it took to build an airplane from weeks to days. The 737 actually moves slowly through the factory at a few inches an hour, and teams of workers assemble it as it moves.

In contrast, the 787 production system is based on a “pulsed” line. With each pulse, the airplane moves its way through a series of positions where specific elements are added to the plane.

Final assembly takes place in a massive hangar in Everett, Washington, where all Boeing wide-body airplanes are produced. This building is about 385,000 square feet (35,000 square meters).

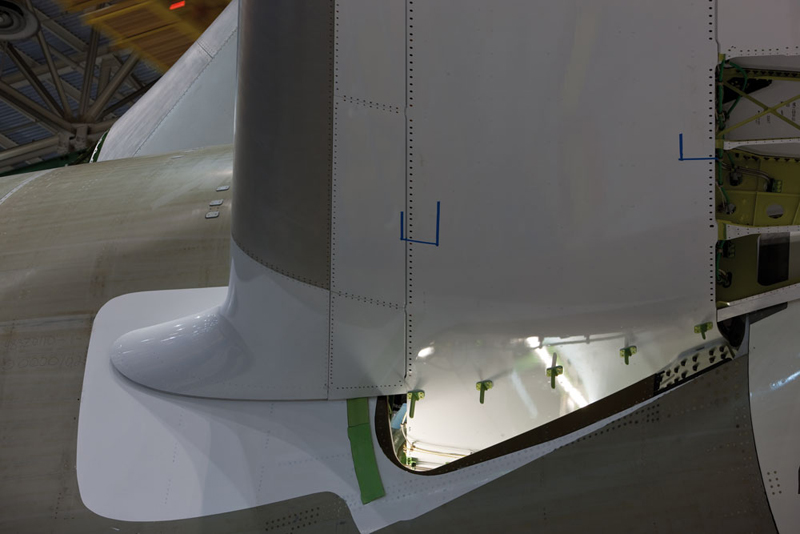

The first spot on the journey from parts to plane is called pre-integration, and it takes place just inside the north end of the factory at Position Zero. Wing tips are added to the larger wing sections and so are parts referred to as “movables,” the flaps and slats. Raked wing tips and leading and trailing edges are also attached to the wing.

Then it’s on to Position One, nicknamed “the Big Bang Join.” Here, the forward fuselage, including the flight deck and the nose of the airplane, and the rest of the fuselage come together. The vertical and horizontal fins at the rear of the aircraft are also added. The production system is based on the concept of “maximum concurrent work,” which means all this activity happens at once.

Kathy Moodie, director of 787 Final Assembly Operations, says, “We don’t have big monument structures and scaffolding like other programs because our partners are sending us stuffed sections.” She says that the pre-installed wiring, plumbing, and hydraulics eliminated a lot of large tools required for access.

But there is one big, spectacular tool in Position One. “We put the vertical fin on with what we call the MOATT,” said Eilers. MOATT stands for Mother of All Texas Towers. According to Eilers, the term Texas Tower goes back forty years. “The 747 was a very large airplane, and it had to have a work platform for the horizontal stabilizers. When the tooling organization completed building it, it looked like an oil-drilling platform.”

The MOATT picks up the vertical fin, lifts it high into the air, and rotates it into position for fastening. “It’s a tool that parts in the center, like a big clamshell,” says Eilers. “When it’s closed, it serves as a work platform.”

The MOATT also picks up the horizontal stabilizer, lifts it up to airplane height, and sets it on jacks using an eight-hook crane system that hangs from the tower of the structure, placing it in the area of the airplane known as “the bird mouth.” It has an elevator in the bottom to upload auxiliary power units. It also provides staircases for the mechanics to reach work platform areas.

Elsewhere at Position One, the huge fuselage barrel pieces are fastened together. Digitally programmed devices on tall stands send out laser beams to help align the sections. Fastening the barrel sections together is done with the aid of an auto-driller, a tool that works its way around the vast circular joints on rails. It drills holes and, after fasteners are installed by hand, countersinks them. The tops of the holes are tapered to accommodate a fastener that’s flush with the surface. “For aerodynamics, you don’t want bumps. When bumps are present, they are commonly referred to as ‘proud fasteners,’” says Eilers.

Although the fasteners look like traditional rivets, there’s no riveting involved. Eilers explains, “They are two-piece mechanical fasteners. We actually invented the fasteners used to put the airplane together because of limited access to the areas of the airplane where they were needed and the unique nature of the material.”

Early in the program, this new fastener technology created a production hurdle. Special tools were required to remove approximately 15,000 fasteners that didn’t meet the Boeing specifications for use on components made of composite and titanium, and they were all replaced. “We had to take the first few airplanes all apart, re-inspect the holes, correct the ones out of specification, and re-install brand-new fasteners,” says Eilers. And, he adds, they had to invent tools and a method specifically designed to remove the problem fasteners. In the end, he says, they invented “several different styles, depending on where the fastener was on the airplane. We were firefighting. We did what we had to do to find a way.”

But once that massive rework job was completed, Moodie says the subsequent aircraft, airplane number three, “snapped together faster than any airplane.”

After all the Big Bang joins are made, the structure, looking like an airplane now, is moved on rails to Position Two, then is raised up 64 inches (162.5 centimeters). Moodie says, “We learned in Position One we want the workpiece—the airplane— as low to the ground as possible. It’s fatiguing to have people go up and down stairs. But then, in Position Two, we raise it up to install main landing gears and engines. Position Two is where we do the floors and secondary structure, and we start finishing up the final systems.” All those stuffed components are packed full of tubes and wires for electrical, hydraulics, and environmental control systems that regulate air-flow and temperatures. And when the airplane comes together, all those tubes and wires have to be connected.

There’s so much in the factory that has never been done before— because it’s an exciting airplane that’s never been done before.

—Todd Eilers, production engineering manager, 787 program

As Position Two is also where the main landing gear is installed (the nose landing gear has already come pre-installed with the front fuselage), Moodie says, “It’s the first time the airplane can be put ‘weight on wheels’ and moved forward.”

The airplane also gets some cleaning in the form of a carbon-dust aqueous wash. Eilers explains, “Wings are fuel tanks. We give the wings a really good cleaning.” The idea is to make sure there’s no dust left over from assembly that can mix with fuel. “It’s like a mild pressure wash with warm soapy water,” he says.

To accommodate this step, there are drains in the factory floor and a huge water tank with pumps and lines. But that’s not all that’s underground. Eilers says, “We dug three Olympic-sized swimming pools, one at each assembly position, and filled the factory floor with utility systems.” They include reservoirs that contain airplane-quality hydraulic fluid so “we can actuate movable surfaces for factory tests.”

There are also buried electrical and ventilation systems. “We needed two kinds of electricity,” says Eilers, “a 60-hertz system for tooling and a 400-hertz system to test the airplane. The 400-hertz is used at airports for ground operations. We dug all these holes, buried all these facilities and utilities needed to manufacture an airplane, and located them coming into the factory floor at specific points of use. That eliminates all kinds of hoses lying all over the factory.” The system is reconfigurable should production methods change later. “We were thinking ahead,” says Eilers.

In an ideal state, says Eilers, Position Two will also be where the engines are installed—this is what’s called “the engine hang.” Once the engines are installed, the airplane can be described as ready for power-on testing.

Moving work to different positions as operations increased was a response to one of the biggest challenges with the new airplane—integrating parts and components from the global supply chain. When problems arose with some of the components that were arriving, changes were made to the plan to keep the line moving and avoid bottlenecks.

Moodie describes the problem. “We had originally provisioned for very little work to be performed here. When the first section came in not quite meeting condition of assembly we were overwhelmed with the amount of traveled work.” “Traveled work” is the Boeing term for work that travels from where it was meant to be performed to final assembly.

“We were going to have 2,600 work orders—small units of work, under four hours long—and we ended up with 20,000.” But, she adds, “It’s all measurable.” Boeing tracks the amount of traveled work and the rate at which it’s being eliminated. By early 2010, says Moodie, they had already eliminated traveled work by 40 percent.

At Position Three, interiors, including carpeting and the lining for the cargo area, are installed. And at Position Four, Moodie says, “We finish interiors so it’s all beautiful.” The galley, lavatories, seats, and stow bins are all added in Positions Three and Four.

At Position Four, there’s also extensive testing. “We test the hydraulic system and put in hydraulic fluid to make sure there are no leaks. We conduct air checks, ducting leak checks, and we’ll do a water test, making sure everything works as designed, and then we do avionics testing, we test flight controls, and we take main landing gear and swing them to make sure they’re functional,” says Moodie.

But she says there were some surprises in store when it came to performing all those tests. Because the 787 is an intelligent airplane, testing produced some interesting challenges. “The airplane is so smart,” says Moodie. “It knows what’s going on. At first, it wouldn’t allow us to shut off certain systems for testing, so we had to develop special blocking systems.”

Quality inspectors monitor the work as it takes place at all positions. Every job, or work order, has to be approved and signed off. In the old days, mechanics and inspectors each had an ink stamp with their own identifying number, and both of them stamped the paper instructions for each task after it was completed and inspected.

Today, because the mechanics and inspectors are all outfitted with the laptoplike electronic tablets, including work instructions and specs, stamping the paperwork is done electronically, too.

The tablets are all part of a shop-floor management software system called Velocity that tracks progress. As the airplanes move down the line, a huge amount of engineering and production data flows electronically to where it’s needed. Drawings, work instructions, and information as detailed as how a specific bolt must be torqued are all made available to mechanics and inspectors on these personal electronic devices.

On the factory floor, each worker has, in addition to one of these electronic tablets, an FOD bag. FOD stands for Foreign Object Debris, and whenever employees come up with or spot an errant fastener, a piece of packaging, shavings, or anything else that doesn’t belong on the airplane, it goes into the FOD bag. FOD prevention measures also include regular sweeping and FOD walks where groups of employees inspect a work area. It’s a safety and quality issue. Tool accountability systems are also in place to make sure objects aren’t accidentally left on the airplane where they might end up behind a panel or underfoot. When Todd Eilers was planning the factory, he took FOD into account and arranged for a special white epoxy floor surface in production areas. “It’s easier for FOD detection, and it provides for a better-lighted work area.”

This was just one of hundreds of elements that he and his team had to invent to get the 787 program up and running. Eilers jokes that they even re-invented the wheel, developing a special caster for tall mobile stands which are pushed toward and away from the airplane for access to certain areas. To avoid the irritating wobbliness every shopper has encountered while negotiating supermarket aisles, they developed a caster that worked in two modes—being pushed toward the airplane and away from it.

Eilers describes his work on the project as “very exciting. And, we came in under cost targets. We did that by establishing a whole new team structure and a very integrated approach, and we had a lot of common processes.” In his years getting everything launched, Eilers estimates he got to know about 90 percent of the mechanics on the floor on a first-name basis. His next assignment is getting the second assembly line going at the Charleston, South Carolina, site. “We’ll have a brand-new facility complete with flight line and delivery center. Our first airplane load in that brand-new facility is projected to be July of 2011.”

The 787 assembly program is built on “lean” principles. Lean manufacturing is based on eliminating waste, using common processes, and building a supply chain that moves smoothly and steadily. Key to its success is a moving line and on bringing parts, tools, and people to precisely when and where they are needed. Tools, parts, and other materials are often collected together or “kitted” for a specific installation, including all the fasteners needed for the job, and are ready for the mechanics at the point of use.

Lean manufacturing also focuses on communication up and down the supply chain, continuous vigilance for inefficiencies, and employee involvement, which encourages solutions and innovations from the design and production engineers, the mechanics who build the parts and assemble the airplane, the inspectors, and the representatives from supplier companies who work daily at the Boeing facility.

Visual cues are another part of lean manufacturing. Clearly marked zones along the line indicate where parts and tools should be delivered; colored lights tell everyone on the factory floor whether or not the airplane is progressing down the line according to plan; and a giant scoreboard provides an overview of how the line is functioning.

These lean techniques have historical roots that go back to World War II, when a Boeing workforce that included many women new to industry responded to wartime urgency by developing a streamlined system for building the B-17 bomber that eliminated scrap and waste, rework, and bottlenecks. In its modern form, lean manufacturing draws on processes pioneered in Japan.

Boeing uses the science of ergonomics to find ways for an employee to do his or her job with as much safety and comfort as possible. In the past, these issues were often addressed on the factory floor, when it became clear some manufacturing operations were awkward or unsafe.

But the 787 program moved ergonomics back to the initial design phase. In a special Boeing virtual lab, 787 design engineers wearing 3-D glasses operated hand controls, taking them through a simulated assembly process to evaluate how their designs would affect access and reach for factory personnel and airline maintenance mechanics.

Ergonomics experts and design engineers worked together and came up with innovations such as a removable panel on the wing that provides a safer installation process, as well as built-in lifting points on heavy items such as galleys, seats, and lavatories. Boeing also developed a process for examining all factory manufacturing instructions to identify ergonomic risks. Mark Arthun, an engineer devoted entirely to 787 ergonomics, explains how it works. “We used historical data from other airplane programs to develop a checklist that identifies ergonomic risks. When the manufacturing engineers write the installation plan for the mechanics, they also go through our ergonomics checklist. It’s a simple, short checklist, trying to capture and address the highest risks.” He adds that because the 787 has human modeling capability, “we can also run simulations at the installation plan level to further understand the ergonomic risks our mechanics are going to encounter in their operations.” His group also addresses any emergent ergonomic issues that are identified by lean workshops, manufacturing technicians, or safety coordinators.

Ergonomic benefits start with the manufacture of the airplane and continue throughout the life of a plane in service. Arthun says, “My background is in industrial engineering and process improvements. But I’m not just improving processes. I’m also directly affecting people’s lives and livelihood. It’s so rewarding when the mechanics come up and say ‘Thanks!’ after we’ve improved a process to reduce ergonomic risk.”

Motorists driving past the Everett plant sometimes see a 787 on a bridge that crosses the freeway. After an airplane is checked out at Position Four, it is towed across the special Boeing bridge to the paint hangar where it receives the livery, or design, of its future owner or operator.

According to Bill Dill, operations manager of decorative paint, “One of the most sensitive things to the customer on delivery day is how the airplane looks.” An airline livery has to be perfectly applied. “That’s very competitive to them,” says Dill. “That’s their brand. They’re putting their brand out there and we want to make sure their brand is something they will be proud of.”

The airplane must be sanded and extensively cleaned before painting. The design is created by masking portions of the surface and painting in stages—starting with a full body coat and then subsequent coats in separate colors of the livery.

In the past, painters measured the airplanes to tape the masking to the airplane according to the precise design, using points on the airplane’s surface as their guide. But on the 787, a computer-programmed device that takes the curvature of the airplane into account uses lasers to beam points of light onto the surface of the airplane to guide the painters as they mask. Dill says the three paint hangars at Everett are the only airplane hangars in the world using a special laser-aided exterior marking system (LEMS), which was conceived by an engineer in the Boeing research and development organization.

Says Dill, “When we developed the marking system, painters worked with the development team because we wanted to make sure it was a system they could use and live with. It took us about a year to get it done and installed. When we did the first trials on a live aircraft we did it on third shift and took a tenured painter with us. When we put the laser light on the airplane, it took him about ten minutes to figure out what to do.”

Each airplane has its own masking computer program— even airplanes from the same airline can have small livery differences, such as registration numbers or the ship’s name. There are computers on work platforms so painters can pull up the program. “Every work platform has a computer on it,” says Dill. “That’s never been done before and it allows the painter to pull up what he needs to know, right in his work area; so there’s less time going to search for specs and work instructions.”

The actual painting of the masked airplane is like a carefully choreographed ballet. There are twelve painters in the team, using electrostatic paint guns. Two are positioned at the nose, two are by the vertical fin, and four are on each side of the fuselage. Another team member, the mixer, arranges for the paint to be properly mixed and ready to deliver to the painters’ guns through hoses. The colors must be mixed precisely to ensure that all the airplanes in the fleet match perfectly. Boeing maintains a database of thousands of customer colors, and new ones are added all the time.

The painters work from ceiling-suspended telescoping work platforms called “stackers,” which move independently from each other and also move up and down. This allows each painter freedom of movement throughout the assigned work area of the airplane. The eight painters have to start and stop at the same time, so they meet up with what’s called a “wet edge.” If paint in one area has been allowed to dry before an adjacent area is painted, there’s an unsightly ridge.

“The application part is orchestrated,” says Dill, and the conductor’s podium is at the rear of the airplane at the top of the vertical fin. That’s because everyone on the crew can see that area and everyone can be seen by the two painters there. “So when everybody indicates they’re ready by looking up, and the two people on the vertical fin see everyone looking up at them, they pull their triggers and everyone starts painting together. Two people work their way aft and meet up, wet edge to wet edge. Other people meet in the middle and overlap wet edge to wet edge. They start at the top and traverse over and down, over and down, and meet up again at the bottom.”

Dill says it takes about three hours to do the initial body coat, and around forty-five minutes to apply each additional color. A typical livery includes a body coat and three subsequent maskings for additional colors, but individual liveries vary. The key to success is to make sure they get what’s called a “full hide,” ensuring that earlier colors won’t show through. But the process also has to be carefully controlled to avoid over-spray. That’s important because, like everywhere else on the airplane, weight is always a consideration. Paint can add hundreds of pounds to the airplane. In fact, the official weighing of the airplane, to make sure the airline customer is delivered a plane within its weight specification, takes place after painting.

Painters using this automated livery layout for masking and paint application equipment are highly skilled technicians. They also have to be perfectionists. “They take a lot of pride in their work,” says Dill. He adds that the paint hangar has “one of the lowest attrition rates in the company. We’ve got one guy here, Bob Filer, who painted the first 747 right here in Everett about forty years ago.”

Dill thinks he knows why the turnover is low. “It’s one of the few disciplines in the build process where you get to go from start to finish and see what you’ve created at the end of the day. We work until we’re done.” The paint hangar operates twenty-four hours a day, and there’s no such thing as a half-painted airplane waiting around for its livery to be finished the next day.

After the paint is on, touch-up and stencil work of small details begins. Then, the paint job is inspected by Boeing and a customer representative of the airline. Dill says, “The customer rep is looking for everything to be aesthetically perfect. They’re looking for a paint run or drips, making sure all the lines are nice and crisp, that there’s no over-spray. They look to make sure everything is exactly where they want it, like the name and logos. The average customer spends between two and four hours but we’ve had customers take up to twelve hours [to inspect].”

When the planes finally leave the paint hangar they will then undergo rigorous flight testing procedures by Boeing and customer pilots before heading to their new homes somewhere around the globe.

The Boeing Everett facility is the largest building in the world by volume. Its footprint covers 98.3 acres (39.9 hectares).

|

The Everett facility, which is acknowledged as the largest building in the world by volume by Guinness Book of World Records, has grown over the years to enclose 472 million cubic feet (13.3 million cubic meters) of space. |

| The Everett aircraft fueling area has room for |

Pre-flight areas can hold |

| 5 | 26 |

| airplanes. | finished jetliners. |

|

Each day, parts and subassemblies come to the plant from all over the globe. More than a thousand suppliers ship components by truck, rail, air, and ship from throughout the world and all fifty states. The major assemblies of the 787 Dreamliner arrive by air, courtesy of a fleet of Dreamlifters, which are specially modified 747-400s. Approximately 30,000 people on three shifts work at the Everett site. |

Cargo loader delivers assemblies

Pre-integration begins

Horizontal stabilizer assembly

|

Spirit AeroSystems, based in Wichita, Kansas, builds the nose section of the 787, also known as Section 41. |

|

The Everett factory was modified to accommodate these large airplane sections. The hangar door is approximately 60 feet (18 meters) tall by 80 feet (24 meters) wide. This was cut into the north end of the final assembly facility because the structure did not already have a door big enough for the parts to enter. |

|

Major assemblies of the 787 reside in the pre-integration area of the factory before moving into the next position—final body join. |

|

In a change from conventional manufacturing processes in which Boeing mechanics installed systems, blankets, ducts, and other electrical components, the 787’s manufacturing plan relies on its partners to complete that work at their facilities before shipping to Everett. |

|

At 84 feet (25 meters) long, the integrated mid-body section of the 787 is the largest assembly on the airplane. It’s composed of sections produced by partners in Italy and Japan and pre-integrated at the Boeing facility in Charleston, South Carolina. |

|

For the first time in Boeing history, the movable surfaces of the wing are tested in the lay-down position before the wings are actually installed on the airplane. |

|

The six major sections of the 787 are placed in the final position to be joined together. The fuselage-and wing-to-body joins occur simultaneously, followed by the installation of the horizontal stabilizers and vertical fin. |

Wing pre-integration

Wing/body join

Forward/aft fuselage join

Tail/fin join to fuselage

|

The engine pylon, shown jutting off the wing, awaits the installation of the engine. For the first time, the two engine manufacturers, GE and Rolls-Royce, designed a common engine interface that will allow airlines to swap engines in a short period of time if necessary. |

|

The horizontal stabilizers and tail cone are joined in the pre-integration so that when they arrive at the next position they can be joined efficiently to the aft section of the airplane. |

|

The horizontal stabilizers and tail cone are placed in the MOATT (Mother of all Texas Towers). |

| Boeing invented |

| two-piece mechanical fasteners |

| to put the |

| 787 together |

| and tools to remove the old fasteners. |

|

The 787 vertical fin is built at the Composite Manufacturing Center (CMC) at Boeing Frederickson in Pierce County, Washington. The CMC is a major structures partner responsible for design, manufacturing, systems integration, and functional test of the vertical fin. |

|

Visible on the floor of the final body join position are tracks that are used when advancing the airplane to the next position until its landing gear is attached. |

|

The radome of the 787 is intricately designed to protect the radar while allowing the radar to operate at maximum capability. |

|

A 787 sits in final body join before the three major fuselage sections are joined. |

|

Two mechanics are using a laser alignment system as part of the join process. |

|

The 787 production system uses a pulse assembly line. Unlike a moving line, the pulse system comprises four discrete production positions where work is completed in a particular sequence. |

Floors/secondary structure

Blankets/insulation

Hydraulics/electrical/systems installation

|

Portable tooling makes the 787 assembly process more efficient. The blue fixture holding the wing carries it from the delivery point through the assembly process. The wheels facilitate moving the wing into position where it is lifted, aligned to the wing stub, and attached. |

|

Once the 787 flight test program concludes, Position Three will be used to install interior components such as seats, gallery, lavatories, and stow bins. |

|

Workstations (left, bottom of image) along each assembly position feature detailed charts tracking the status of each airplane. |

|

Located on the fourth floor of the facility, the Production Integration Center(PIC) overlooks the 787 production line. |

|

The PIC serves as an operations center for real-time, around-the-clock monitoring of the worldwide team of 787 partners. |

| WINGS |

| are flexed upward by about |

| 25 feet (8 meters) |

| in the static test. |

|

During testing on the 787 Dreamliner static test airframe, the wing and trailing edges are subjected to their limit load—the highest loads expected to be seen in service. |

|

The 787 static test facility comprises a large steel superstructure erected on a reinforced concrete slab capable of reacting to the test loads. The steel superstructure is 208 feet (63.4 meters) wide, which allows for a free span greater than the wingspan of the 787 airframe. |

|

The 787 Dreamliner fatigue test airframe sits in its test rig in the northwest corner of the Everett site. Unlike static tests, in which loads are applied to the airplane structure to simulate both normal and extreme flight conditions, fatigue testing is a much longer process that simulates up to three times the number of flight cycles an airplane is likely to experience during a lifetime of service. |

|

More than 15,000 hours of wind-tunnel time have been logged to develop the 787-8 at a variety of wind-tunnel facilities. |

| Under the factory floor are |

| 3 |

| Olympic-sized |

| swimming pools filled with |

| UTILITY SYSTEMS. |

Interiors/cargo/payload installation

Engines

Airplane power-on

Initial testing

|

Two views of the 787 Dreamliner’s left horizontal stabilizer. |

|

The primary purpose of the tail cone is to contain the 787’s auxiliary power unit. |

ANA is the launch customer of the 787 Dreamliner with an order for fifty airplanes. This is the first time a non-US customer launched a new airplane for The Boeing Company.

Interiors completed

Production testing

|

Gray pads allow mechanics to stand on the wing without damaging the surface. Railing contains the area they can access without wearing a safety harness. |

|

Mechanics prepare the 787 to be tugged to the paint hangar. |

| The airplane is so |

| smart |

| it knows what’s going on. |

| At first, it wouldn’t allow us to shut off certain systems for testing, so we had to develop special blocking systems. |

| —Kathy Moodie, director of 787 Final Assembly Operations |

|

Airplane painters use the laser-aided exterior marking system to aid them in the masking process. |

| The paint hangars at Everett are the only airplane hangars in the world using |

| LEMS |

| (a laser-aided exterior marking system). |

|

The painting process can last a number of days, depending on the complexity of the airline livery. Paint is applied one color at a time and needs to dry completely before the next color is added. |

|

Masking is removed at the end of the process, revealing a perfectly applied customer livery. |

|

The first 787 Dreamliner in Boeing livery. |

|

The first 787 Dreamliner sports the new livery in front of the Everett factory. |