A brand-new airplane may begin with a dream, but nothing can be achieved without the nuts and bolts of experimentation and testing. With the stage set and the skies cleared, the first flight of the 787 Dreamliner took place on December 15, 2009. The aircraft elegantly ascended from Paine Field in Everett, Washington, to the rapturous applause of a crowd of more than 12,000 Boeing employees and guests. Inside the flight deck, Chief Pilot Mike Carriker and Captain Randy Neville tested some of the airplane’s systems and structures, and on-board equipment recorded and transmitted the data to a team on the ground. First flight was an emotional and exhilarating moment for those who had worked long and hard on designing and building the Dreamliner, but it was just the begining of many more flight tests to come.

Structural testing began years before with small blocks of composite materials that were subjected to stresses, strains, fire, and freezing. Parts were made some the size of a fuselage barrel to learn how the materials performed in the shape of the airplane. Then, pieces were combined, and testing began all over again.

Boeing also built two ground test 787s destined never to fly the static test and fatigue test airplanes. The static test airplane was tested to over 150 percent of the most extreme load conditions. Using a series of weights and counterbalances, it was lifted off the ground to simulate flight and subjected to severe bending and twisting. The wings were flexed upward by about 25 feet (8 meters) and the fuselage was pressurized to 150 percent of its maximum normal operating condition. Afterwards, specialists pored over thousands of data points collected during the tests.

Whereas the static test airplane demonstrates the ability to deal with one-time extreme events, the fatigue test airplane scrutinizes how the structure will cope with a lifetime of flying service. Tests for the fatigue airplane replicate three times a Dreamliner’s anticipated working life. In addition, systems and software were tested in laboratories in south Seattle and in an integrated power systems facility at Hamilton Sundstrand in Rockford, Illinois. Systems were then combined in Seattle to ensure they worked properly together.

Before first flight, the first on-airplane engine runs were completed. The engines were operated at various power settings and basic systems checks continued throughout the test. The engines were powered down, inspected, and restarted. The team completed a vibration check and monitored the shutdown logic. “We were very pleased with the performance on the engines during this test, says Scott Fancher, vice president and general manager of the 787 program. Completing engine runs allowed us to move forward with intermediate and final gauntlet tests.”

In gauntlet testing, pilots and engineers simulated multiple scenarios using all airplane systems as if the aircraft were in flight, including power, avionics, and flight controls. These tests were run around the clock for days on end to simulate operations in normal and abnormal conditions. Certain systems were turned off to simulate a failure to test backup systems.

High-speed taxi testing was the last functional testing performed before first flight. During the testing, the airplane reached a top speed of about 130 knots (150 miles/240 kilometers per hour), and the pilots lifted the nose gear from the pavement.

Finally, after the successful first flight, the pilots were able to add to test results how it actually felt to fly the airplane. Flight test is one of the final phases of verification of the operational characteristics and overall performance of a new airplane. Like laboratory testing, flight testing is a means of demonstrating that the design intention is being fulfilled by the airplane.

The data collected during flight test is part of the information required by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and other regulatory agencies to certify that a new airplane meets all the requirements of the Federal Aviation Regulations (FAR) and is ready to enter revenue service with airlines around the world.

When Boeing began to plan the 787 Dreamliner, its dream was to address some specific challenges: increased global activity and growing economies in vast countries such as India and China meant there was a burgeoning need for more airplanes to connect more cities all over the globe. Climate change had made clear the urgent need for transportation that reduced fossil fuel emissions and conserved resources. Commercial aviation faced staggering business challenges as the price of fuel rose, security concerns increased, and airports and airspace became crowded, creating delays and expense.

But there was one more very important part of the dream. Flying had lost its magic. Fancher sums up the design of the 787 as “a combination of outstanding operating economics and restoring of the joy of flight. It is a real one-two punch. We combined new technologies to provide a more economical airplane than ever before.”

How do you give an airplane a distinct personality? That was the challenge given to Blake Emery, director of differentiation strategy at Boeing. When the Dreamliner was still just a dream, Emery, a psychologist by training, led research all around the world to find out how people felt about flying and what they wanted and needed when they were on an airplane. Emery says, “When people were asked to talk about early flying experiences, one of the surprises was that these experiences were always related as positive. Consistently in every country we ve been to, regardless of age, gender, or culture, the flying experience was positive. The flight attendants were always attractive, the takeoff amazing, the first view of your city beneath your feet was always magical. Flying and being up in the air is mankind’s oldest metaphor for freedom.”

But Emery knew that the magic had slipped away. “Flying is a wonderful, joyful experience, and over the years the industry beat the joy out of it.” The Dreamliner was envisioned as a way to turn that around. “We came up with a strategy that said, ‘We are going to meet the unarticulated needs, the deep psychological needs of people in contact with the airplane.’ And we were pretty much going to start with the passenger experience. We called it ‘airplanes for people.’”

We are going to meet the unarticulated needs, the deep psychological needs of people in contact with the airplane.

—Blake Emery, director of differentiation strategy at Boeing

The name of the 787 reflects how people around the world yearned for a new kind of flying experience. In May 2003, Boeing launched a global “Name the Plane” contest with its partner AOL Time Warner. Four names were considered: Global Cruiser, eLiner, Stratoclimber, and Dreamliner. The contest drew nearly half a million votes from aviation enthusiasts in more than 160 countries.

Just days before the competition closed, Global Cruiser was winning. But the tide turned in favor of Dreamliner by fewer than 25,000 votes.

Why do we want to fly? “First, people are fascinated with flying and love to feel connected to the experience of flight as it happens. Second, passengers should be welcomed to the airplane to help them leave the annoyances of the airport experience behind them. What we learned drove the design process,” says Klaus Brauer, former director of passenger satisfaction and revenue for commercial airplanes. Boeing research conducted in cities around the world concluded with these two key desires.

The cabin design is like no other. In the words of Chris Browne, managing director of Thomson Airways, “The new interior of the 787 is going to blow our customers minds away. It will be absolutely fantastic...bigger seats, wider aisles, bigger windows, we have mood lighting, [and] it’s going to a whole new level.”

As passengers are welcomed aboard the 787, they will notice tall sweeping arches designed to direct the eyes upward to a simulated sky. The sky is created with light-emitting diodes, and can change color and intensity to create natural-looking lighting from dawn to dusk. During boarding, the Dreamliner can feature the airline’s own colors, then change to something more relaxing during takeoff. While the aircraft is cruising, the light can be crisp and clear for working and reading. During dinner, lighting can simulate the warm glow of candlelight. Passengers can go to sleep after a simulated sunset and awaken slowly, as in nature, with a sunrise. The psychological effect on passengers is restful and soothing.

But it isn't all a carefully engineered illusion. The 787 actually has bigger lavatories. And the overhead luggage bins, which can also pivot upward and out of the way to give passengers an unobstructed view of the cabin architecture, are the biggest in the industry. The windows at 19 inches (48 centimeters) tall and 11 inches (28 centimeters) wide are the largest on any current commercial airplane and will give all passengers, regardless of where they are sitting, a view to the horizon due to precise engineering that determines the line of sight of passengers in every seat.

Bulky window shades have been eliminated. Instead, the opacity of the electrochromic windows is electronically controlled. Auto-dimming “smart glass” works like sunglasses to reduce cabin glare while maintaining transparency. The flight crew can also control the level of outside light flooding into the cabin with these electronic window shades while still giving passengers the ability to see outside.

Says Scott Fancher, “The flying experience was an embedded part of the design requirements. The sense of spaciousness that this interior provides through lighting, larger windows, and through the geometry of ceilings and overhead bins put them all together and it results in a flying experience where the passenger can truly connect to the flying environment.”

During flight, one of the biggest factors in passenger comfort has nothing to do with the sense of sight. It’s the air inside the cabin that makes a big difference in how people feel. Boeing studied the effects of temperature, humidity, and air purity on passenger comfort in a two-year cabin environment study conducted in collaboration with the Denmark Technical University. Subjects experienced prolonged exposure up to eleven hours—at different humidity levels, with and without air purification.

Participants reported on their perceived ratings of air quality and the intensity of a number of symptoms such as level of eye and throat irritation, dryness, headaches, and general comfort. Researchers also ran objective medical tests to measure the effects on the eyes, nose, and skin.

Initially, the researchers believed that humidity was the key factor in passenger comfort. But there were surprises. Air purification was found to be a more important factor than increased humidity for addressing many aspects of passenger complaints. They found that a reduction of gaseous contaminants from all kinds of sources including passengers perfume and hairspray together with modest increases in humidity, is the combination that provides maximum improved passenger comfort.

Airplanes already had filtered recirculation systems based on High Efficiency Particulate Air (HEPA) technology used in hospital operating rooms. But additional air purification on the 787 exceeds those standards by removing gaseous contaminants as well as particulates such as allergens, bacteria, and viruses.

Another important comfort improvement is a smoother ride, made possible by a gust suppression system. It will reduce those bumpy patches where pilots ask passengers to return to their seats and fasten their seatbelts.

And the cabin is quieter, too. Quieter engines and changes to the nacelles that house the engines reduce the noise. Turbine noise irritating to humans because of its high frequency is also reduced with special acoustic linings in the exhaust.

One of the biggest changes in the passenger experience is the way passengers will feel when they arrive at their destination: the decisive factor here is cabin pressure.

Traditional commercial airplanes are certified to a maximum altitude equivalent of 8,000 feet (2,438 meters) to minimize structural fatigue to the airframe during normal operation. The 787 will be pressurized to a maximum altitude equivalent of 6,000 feet (1,829 meters) during normal operation.

So, while passengers cruise in the 787 at a height of 35,000 feet (10,668 meters), the cabin altitude stays at an elevation of 6,000 feet (1,829 meters) about what you d find at a ski resort such as Sun Valley, Idaho, or Arlberg, Austria approximately 1,970 feet (600 meters) less than most commercial jetliners flying today.

To find out just how much cabin pressure affected the well-being of passengers, Boeing conducted research with Oklahoma State University. The study was based on US Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine methodology characterizing sixty-eight possible altitude symptoms.

More than 500 participants, chosen to reflect the gender and age proportions of the flying public, experienced a twenty-hour flight regime in an airplane-cabin simulator. They did what people normally do on a long flight: sat in standard economy-class seats, ate typical airline food, watched movies, and slept.

The simulator was pressurized to five different altitude equivalents, and each level was tested nine times. Before and after the simulated journey, the participants completed surveys and underwent memory, coordination, and visual tests.

The study indicated that discomfort at higher altitudes usually became apparent after five hours. But even after a simulated twenty-hour flight, study participants reported feeling less achy, more relaxed, and more comfortable with the 6,000-foot cabin pressurization.

Composites make this improvement possible because they are not subject to the same fatigue conditions that limit the amount of pressure cycles that can be applied to an aluminum airplane.

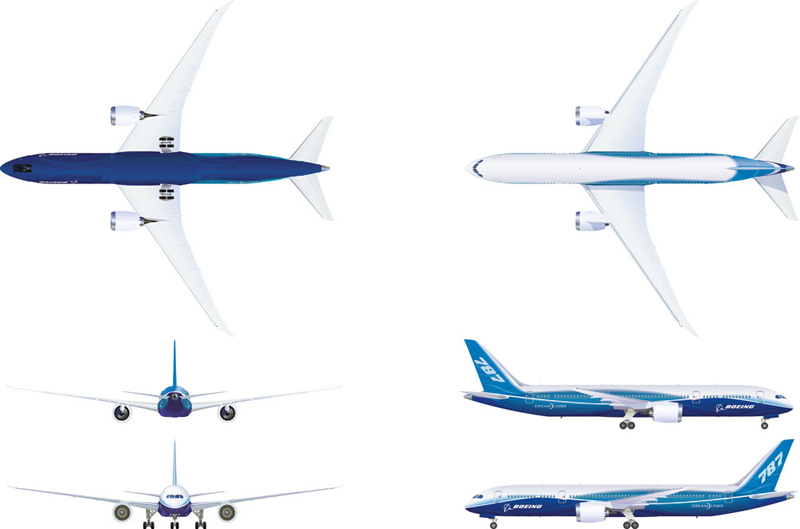

Adding to passenger satisfaction is the aesthetic of the exterior design. Blake Emery recalls, “When we came out with the idea for the new airplane, we were going around the world telling customers, ‘This is a game changer. It’s the newest thing. Trust me, it’s all new.’ But it looked exactly like a 767.”

Emery’s team conducted research to reveal what people found attractive in an airplane and what they didn’t. They worked with industrial designers to create an exterior that looked beautiful and different, both in the air and on the ground. Emery took the futuristic drawings to the engineers and asked them what design elements were feasible. It was a brand-new way to design an airplane, and there was some skepticism from traditionalists. Today, Emery cherishes a note he received from Justin Hale, former 787 chief mechanic, the day after the airplane’s first flight:

“Blake, I never thought I would be writing this note, because I never thought I would appreciate the aesthetics of our exterior differentiation effort. Frankly, I thought E[xterior] D[ifferentiation] considerations were getting in the way of good airplane design. I m writing to tell you how wrong I was. On Tuesday morning, the 787 became without question the most magnificent airplane to ever grace the skies; she was absolutely stunning. Thanks for holding the line and making sure we designed a distinctive and truly beautiful airplane.”

Together with the new engines and use of composite materials, efficient electrical systems and improved aerodynamics make a more economical plane.

Mike Sinnett, vice president and chief project engineer of the 787 program, explains, “Airplane systems are the unseen networks that make the airplane work.” A traditional pneumatic system pumps air “bled” from the airplane engines through a titanium duct system built into the structure of the aircraft. The bleed air powers a wide variety of systems, including thrust reversers, wing flaps, cabin air-conditioning, wing anti-ice systems, and hydraulics, which in turn power landing gear, brakes, and nose wheel steering.

On the 787, this system is powered by electricity instead, which is more efficient from a volume and fuel burn perspective. Sinnett says, “The 787 is more electric than any other commercial jetliner. It’s helping us keep the airplane light and efficient.” A significant amount of the Dreamliner’s overall 20 percent reduction in fuel burn is a result of the “no-bleed” systems architecture. When air isn't bled, all of the high-speed air produced by the engines goes to thrust; so thrust is produced more efficiently, conserving fuel, allowing the airplane to go farther, and reducing emissions. Maintenance costs are also lowered.

The 787 flight controls use electronic fly-by-wire technology. Traditional cable and direct linkage systems are replaced with remote electronic units placed throughout the airplane, near to the surfaces they control. An advanced, fully augmented, full authority, three-axis flight control system receives digital signals from the flight deck, other systems, and sensors, and calculates commands that are converted to analog signals to control surface positions. Advanced flight control laws have also allowed for further reduction of several thousand pounds of structural weight.

Flight controls allow the pilot to obtain desired aircraft attitude, lift, and drag through a set of exterior control surfaces, including flaps, slats, ailerons, spoilers, flaperons, elevator, and rudder. The cables, pulleys, and drums of traditional systems have been replaced with more lightweight wiring, again contributing to the airplane’s lower weight.

Sinnett explains that an open-systems architecture allows for more flexibility. “Because of the airplane’s architecture it will be easy for an airline to make changes and easier still for an airplane to be moved from one fleet to another. The 787 provides ultimate flexibility and is truly a new airplane for a new world, a new century, and a new experience for the flying public.”

Sophisticated computer software tools were used to create the most aerodynamically efficient design possible, enhancing lift and reducing drag. The design was then validated in actual wind tunnels around the world.

It took 15,000 hours of wind-tunnel tests to develop the advanced shape of the 787. Using software allowed engineers to test hundreds of design variants in the time it would take to test a single physical change in a wind tunnel. These tools made it possible to subtly refine the shape of the aircraft to get optimum results.

There were also aerodynamic benefits from the use of composites. Composites allow for thinner wings and for more variation, such as curvature across the surface and raked wing tips. The raked wing tips are highly tapered wing-tip extensions about 17 feet (5 meters) long. They help reduce takeoff field length, and they increase fuel efficiency and climb performance, providing aerodynamic efficiency for long-haul routes.

Saving fuel allows the 787 to provide a salient environmental benefit—more direct routes. Traditionally, there wasn’t enough passenger demand for an airline to operate many long-haul itineraries with a large airplane. In the aviation world, these are called “long, thin routes”: for example, Munich to Nairobi, Vancouver to São Paulo, Auckland to Beijing, Madrid to Manila, Singapore to Geneva, or Manchester to San Francisco.

But with the 787, these routes and hundreds like them can be flown efficiently because the airplane has the range of a big jet but the seating capacity of a mid-sized jet. Boeing has identified 450 new city pairs that are now efficient to fly with the 787.

Fuel is conserved because routes are more direct, the routes offer more convenience and less stress for travelers, and pointto-point travel also addresses one of the biggest fuel wasters in civil aviation—the fuel burn of airplanes stacked up waiting to land at congested hubs. Decreasing the number of landings and descents, when fuel burn is at its highest, obviously conserves fuel.

Another measure of environmental performance is noise reduction. Boeing’s acoustical engineers were given the task of reducing the 787 Dreamliner’s sound footprint the distance across which disturbing noise is heard. They use a number of new technologies to curb sound, including acoustically treated engine inlets, chevrons—the distinctive serrated edges at the back of the engine and other special treatments for the engines and engine casings. The result? The noise footprint of the 787 is more than 60 percent smaller than those of today’s similarly sized airplanes.

Advanced sales of the 787 won it the distinction of being the most successful new airplane launch in the history of Boeing, outpacing the popular 747, 777, and even the 737 Next-Generation for the same points in history relative to launch. Airlines were excited. The first company to sign up was All Nippon Airways (ANA). Its executive vice president of corporate planning, cargo marketing, and services at the time, Keisuke Okada, said, “We are going to fly this new airplane first in the world so we can give our precious customers a nice surprise.”

The obvious economic advantage for airlines is the 20 percent reduction in fuel costs. Another significant expense for airlines is maintenance. Airplanes need to be regularly inspected and maintained to ensure reliability and safety. Because composite designs don t have the same fatigue or corrosion characteristics as typical metal designs, the inspection intervals for the 787 can be spread out over more time.

The composite structure is significantly more robust against the impacts that most often damage aircraft today. This robustness means fewer damage events overall for the airlines to contend with. Boeing has preserved bolted and bonded repair capability in the 787’s structure. This means airlines will have the broadest selection of repair types possible when choosing how to fix their aircraft.

Repair time has also improved because of composites. Just as automobiles are at risk for “parking-lot rash”—scrapes and nicks from other cars—airlines have to contend with “ramp rash” when ground vehicles such as baggage carts and food service delivery vehicles bump into airplanes and damage the skin. Boeing has developed new techniques that allow minor damage to be repaired in about an hour.

Reaching the area that needs to be serviced has traditionally been one of the most time-consuming aspects of maintaining an airplane. The 787 makes it easier for mechanics to gain direct access to areas of the airplane that require frequent maintenance without removing components or fixed portions of structure.

Another headache for airline mechanics has been paperwork. Airplane maintenance has exacting requirements, and repairs and maintenance must be performed and documented properly. Mechanics can spend a lot of time searching for the right form or manual. The 787 comes with digital tools and databases that replace volumes of printed materials. The graphic and textual database has point-and-click features for more details, allowing mechanics to navigate through multiple documents to get the answers they need.

The genius of the 787 system is that it’s not “documents” at all. It is pure data. Underlying any given bit of data is something called “metadata.” Metadata can be viewed as data about data. This way of formatting and managing all the support information about the airplane lets operators dynamically and seamlessly generate and deliver to the mechanic the exact stream of information needed to complete an end-to-end maintenance action. It permits a level of integration between discrete data sources that’s never before been possible.

At maturity, the 787 will cost 30 percent per year less than the Boeing 767 to maintain and the savings will get better each year after that.

Airline crews will enjoy an improved working environment in the 787. Larger display screens provide twice the display area of the 777. Origin and destination airport maps showing taxiways are displayed. Dual Electronic Flight Bags provide the pilots with maps, charts, manuals, and other data. And dual heads-up displays (HUD), one each for the pilot and co-pilot, are standard on the airplane. HUDs display information on clear screens mounted at eye level so the pilots can see flight data while also looking out the windows.

Other features specially designed for the pilots include a quieter atmosphere, additional stowage, more writing surfaces, more standing headroom, more ergonomically designed seats, and even bottle and cup holders, as well as a fresh new look. However, from an operational standpoint there is very little difference between the 787 and the 777; so 777 pilots can be fully trained for 787 operations in only five days.

Pilots and cabin crews also benefit from the overhead crew rest areas that include berths and mattresses, allowing them to stretch out in privacy to rest on long flights.

In 1910, a hundred years before the 787 took to the skies, William Boeing, a lumberman from Seattle, Washington, traveled to Los Angeles to attend an international air meet. The star of the event was French flying ace Louis Paulhan. Bill Boeing was enchanted. He chatted with Paulhan and asked him about this exciting new technology flying machines. Boeing went back home to Seattle determined to get into the airplane business. Six years later, in 1916, Bill Boeing hired his first aeronautical engineer, Beijing-born Wong Tsu. Boeing asked Wong to build a seaplane for US Navy training, and Wong came up with an inventive design, cutting down the vertical fin, using the wings as the horizontal stabilizer, and setting the upper wing slightly forward of the lower one. The Navy was delighted, and the resulting contract launched The Boeing Company.

Almost a century later, its descendant, the 787 Dreamliner, seems light years apart. But what the Dreamliner and that first Boeing airplane have in common is that they are built on innovation. It’s basic to building airplanes.

And, after that innovation comes the huge effort to make the dream a reality. According to Walt Gillette, vice president of airplane development for the 787 program until his retirement in 2006, “Every time we sign up for a program like this one, that is going to be a new standard for the world, it is a near-death experience. We have to set targets that are so far out there that we almost die getting there. If we don’ t, then we have not set the target far enough and what we do will be very short-lived. If we barely survive then we set the right targets because we will create something that will endure for a very long time.”

And a huge part of that effort is persistence. Gillette said, “Apparently Mother Nature doesn’t want humans to fly so all the time we have to take on all the laws that Mother Nature has created. We have to resolve tens of thousands of things that don’t work. After Thomas Edison finally made a light bulb that worked, a reporter asked him, ‘After 18,000 failures you finally have one that works.’ But Edison replied, ‘I’ve never had a failure. I have 18,000 successes that taught me something.’ That’s the way it goes. We test everything until it fails and we know the boundary. We expect one disappointment after another. So the airplane never disappoints in service.”

While the 787 showcases today’s innovations, the groundwork for the future is already being laid. Scott Fancher says, “I’ve been with The Boeing Company for my entire career, and I must say that this has been the most exciting program that I ve been involved with. It’s a truly graceful airplane on the ground, and a beautiful airplane to watch in the air. As the airplane matures we ll continue to evolve its capability. The basic technology composites, nearly all-electric architecture, these technologies are here to stay and we will continue to develop them.”

One example is the advanced auxiliary power unit that supplies power to systems on the airplane, such as cabin lighting. Because it provides only electric power and no high-pressure bleed air, it can be replaced someday with any technology that produces electric power. For example, it could be operated with a fuel cell, an electrochemical device that converts hydrogen into electricity with none of the byproducts of combustion, such as carbon dioxide. Other than heat, water is its only exhaust. In 2008, Boeing flew an experimental fuel cell demonstrator airplane for the first time in history, and work continues to develop this technology. In another lab, Boeing scientists are growing vats of oil-rich algae to research sustainable ways to make it into jet fuel.

In the century or so since human ingenuity made the seemingly impossible notion of manned flight come true, we ve found better, longer, faster, higher, safer, greener, and more comfortable ways to fly. More dreams and inventions will come—but right now the journey to the future of civil aviation is flying on the wings of the 787 Dreamliner.

|

The first 787 Dreamliner flight-test airplane arrives in May 2010 at Moses Lake, Washington, for flight testing. |

“The new interior of the 787 is going to blow our customers’ minds away… it’s going to a whole new level.”

—Chris Browne, managing director of Thomson Airways

|

The 787’s architecture is welcoming to passengers. The tall, dramatically lit entryway creates a sense of the sky overhead. |

|

Business-class seating is typically six abreast on a Dreamliner. The skylike ceiling treatment is continued throughout the cabin.

|

|

The arched entryway lets passengers know that they have arrived in a new space. |

|

The skylike cabin ceiling is illuminated by an array of energy-efficient light-emitting diodes, and the ceiling’s brightness and color can be controlled in-flight by the crew. |

|

With its spacious entryway, newly designed bin latches, and bigger overhead bins, the 787’s design will improve passengers’ comfort significantly. |

The 787 is the first commercial jetliner to engage a filtration system that removes gaseous irritants, odors, allergens, bacteria, and viruses.

|

The overhead bins are the largest in the industry. They are designed to store the variety of carry-on bags that passengers typically bring on board. As a result, every passenger will be able to place a bag in an overhead bin. |

|

Significantly larger windows give passengers a view of the horizon from any seat on the airplane, enhancing their flying experience. |

| Windows in the 787 are |

| 65% |

| larger |

| than in similarly sized airplanes. |

|

Airline flight crews enjoy an improved working environment in the 787. |

|

Various aspects of the 787 flight deck, from flight controls to situational awareness tools, allow the pilots to be as efficient as possible. The center control unit stationed between both pilots is home to radios, throttles, flap controls, the speed brake, and flight-management computers. |

|

Dual heads-up displays, one each for the pilot and co-pilot, are standard on the 787. Larger display screens provide twice the display area of the 777. |

|

Looking through the heads-up display from the co-pilot’s perspective in a 787 simulator. |

|

The 787 is staged on the Everett, Washington, flight line the night before its maiden flight. |

|

The 787 taxis past approximately 12,000 employees and guests on its way to Paine Field in Everett, Washington, for its first flight. |

|

The newest member of the Boeing family of commercial jetliners takes off at 10:27 AM local time on December 15, 2009. After takeoff, the airplane followed a route over the east end of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Chief Pilot Mike Carriker and Captain Randy Neville took the airplane to an altitude of 13,200 feet (4,023 meters) and an airspeed of 180 knots or about 207 miles (333 kilometers) per hour, customary on a first flight. |

|

The first flight of the Dreamliner was a proud and historic day for all who were involved with designing and building the airplane. |

|

The 787 taxis along Boeing Field in Seattle, Washington, after completing its first flight. |

|

Chief Pilot Mike Carriker shows his excitement after landing at Boeing Field in Seattle, Washington. |

Twenty years from now, I believe that rainy day in December 2009 will be viewed as one of the most important in the history of this company and commercial aviation. It will be remembered as a day that fundamentally changed the way airplanes are built, how people travel, and once again proved the kind of company Boeing is—a company of vision that is always pushing technology and advances in flight.

—Jim Albaugh, president and CEO of Boeing Commercial Airplanes

|

After approximately three hours, the first 787 Dreamliner lands at 1:33 PM at Seattle’s Boeing Field. |

|

Whether among the crowd, with family members, or standing solo, everyone witnessed the first flight of the 787 from their own vantage point. |

|

From left: Scott Fancher, vice president and general manager, 787 program, Captain Randy Neville, and Chief Pilot Mike Carriker address the media at a press conference following the first flight. |

|

A Rolls-Royce Trent 1000 engine is the first to power a 787 Dreamliner. |

I never thought I would appreciate the aesthetics of our exterior differentiation effort… [After seeing the first flight] the 787 became without question the most magnificent airplane to ever grace the skies; she was absolutely stunning. Thanks for holding the line and making sure we designed a distinctive and truly beautiful airplane.

—Justin Hale, former 787 chief mechanic, note to Blake Emery, director of differentiation strategy at Boeing

|

A view from under the wing looking toward the back end of the airplane. |

|

The raked wing tips are approximately 17 feet (5 meters) in length and provide aerodynamic efficiency for long-haul routes. |

|

The window shades are dramatically different from those on other commercial jetliners. Electrochromic window shades, as opposed to physical shades, give passengers the ability to dim the windows and still see the passing terrain. |

|

Control surfaces on the wing are shown at different settings. |

|

One of the benefits of the advanced wing on the 787 Dreamliner is that it has been designed to smooth out the ride in moderate turbulence, providing a more pleasant experience for passengers. |

|

Composites allow for thinner wings and for more variation, such as curvature across the surface and raked wing tips, which help reduce takeoff field length and increase fuel efficiency and climb performance. |

|

The 787 tail stands 55 feet, 6 inches (16.92 meters) from the ground. |

|

The mission capability of the 787 Dreamliner also provides an environmental advantage, allowing airlines to offer more direct flights and connect as many as 450 mid-sized cities.

The 787 Dreamliner cabin is climate controlled. Humidity inside the 787 cabin is higher than in other commercial jetliners, helping to reduce the symptoms of dryness. |

The 787 is truly a 21st-century airplane—its extensive use of composites and advanced aerodynamics transform the economics of flight and contribute to a cleaner environment. The 787 reshapes this industry, and for passengers, it will restore the magic of flight.

—Scott Fancher, vice president and general manager, 787 program

|

While passengers cruise in the 787 at a height of 43,000 feet (13,106 meters), the cabin altitude stays the same as at an elevation of 6,000 feet (1,829 meters)—about what you’d find at a chalet in Sun Valley, Idaho, or Arlberg, Austria—and approximately 2,000 feet (610 meters) less than most commercial jetliners flying today.

One of the advantages of the new system’s architecture is that it extracts as much as 35 percent less power from the engines than traditional pneumatic systems on today’s airplanes. |

Seating: 210 to 250 passengers

Range: 7,650–8,200 nautical miles (14,200–15,200 kilometers)

Configuration: Twin aisle

Cross-Section: 226 inches (574 centimeters)

Wingspan: 197 feet (60 meters)

Length: 186 feet (57 meters)

Height: 56 feet (17 meters)

Cruise Speed: Mach 0.85

Total Cargo Volume: 4,400 cubic feet (124 cubic meters)

Maximum Takeoff Weight: 502,500 pounds (227,930 kilograms)

Program Milestones:

• Authority to offer late 2003

• Program launch April 2004

• Assembly start 2006

Seating: 250 to 290 passengers

Range: 8,000–8,500 nautical miles (14,800–15,750 kilometers)

Configuration: Twin aisle

Cross-Section: 226 inches (574 centimeters)

Wingspan: 197 feet (60 meters)

Length: 206 feet (63 meters)

Height: 56 feet (17 meters)

Cruise Speed: Mach 0.85

Total Cargo Volume: 5,400 cubic feet (153 cubic meters)

Maximum Takeoff Weight: 545,000 pounds (247,208 kilograms)

For my parents, who were supportive in all ways and who always believed in me and my abilities. My family has always been there and kept me motivated. For my three main mentors at Boeing: Larry Veltman, Dick Stefanich, and Fred Kelley, who guided me at key points in my career and made sure I didn’t take myself too seriously. And to Scott Lefeber and Yvonne Leach, who put up with me throughout this project and kept me focused.