3

Strategic Decision Making

What values must be recognized and nurtured before, during, and after the planning cycle in order to maximize strategic planning? Leadership needs to understand and encourage strategic thinking, select the best decision-making style to be used during the process, clarify the ethical premises that underlie discussions about the community’s most difficult topics, and address the potential effects of the resulting plan on the local government workforce.

At this point, it is appropriate to comment about the people who will be doing the planning. Usually a relatively small planning committee is appointed, and it includes local government officials as well as representatives of the community. This committee is responsible for organizing the process and making final decisions on the resulting plan. The following thoughts on strategic thinking, decision making, ethics, and human resource management apply mainly to this group and to managers involved in implementing the planning process and the plan itself.

Strategic thinking

Too frequently, strategic plans end up being little more than an endorsement of the status quo. Industry and government suffer from the same problem. Although it is possible to imagine a time and a place in which the status quo of the past five years makes perfect sense for the next five, it is highly unlikely.

The existing activities and objectives of some program areas might change very little, but, on the whole, a plan for a city or county will probably need to change significantly from one period to the next.

Often, what causes communities’ plans to be reauthorized rather than reevaluated and restructured is the absence of serious strategic thinking. Stagnant plans follow from an insufficient review of what has worked, or not, and why. Even more important, stagnation is generally the result of planners not taking the time to think about the future environments in which the community will exist.

Consider the environments that give rise to factors that affect the futures of our communities. It is self-evident that changes locally and in the immediate region will make an impact on everyone’s life and activities. Changes in the state will also change what happens in our daily lives.

National events and decisions have an impact on localities, too. Consider, for example, how expenditure to support the armed forces limits funds available to states and how those changes get passed on to localities. Consider also how unfunded federal mandates affect local expenditures for public services. Even global events influence local decision making.

Changes in technology, in educational practices or testing, in clean air and environmental regulations, for example, all make an impact on localities. Local officials cannot see all these changes coming, and very few changes can be anticipated unless the official view is forward in time and not backward. If the changes are not anticipated, communities can neither avoid the changes, minimize the impact of the changes, nor, alternatively, take full advantage of them. They can only react.

Strategic thinking requires looking forward critically at how future events could potentially impact the community and how the community’s leaders should prepare for and address future changes if and when they occur. The strategic thinking mind-set must be encouraged at all levels in the local government. Leadership as well as first-line supervisors and even those on the front lines can think about what forthcoming changes will affect their specific areas of responsibility. All such intelligence can be gathered at the top of the organization and applied more or less informally every day.

Strategic thinking is an art that can be cultivated. A community that is conducting its first strategic planning exercise—unless participants have engaged an experienced facilitator—tends to concentrate on numbers. What has happened—or not happened—and why? Could we do more? Could we do it less expensively?

Communities whose strategic planning processes have matured still take careful notice of numbers but use them only as a basis for understanding the inherent concepts. The fully matured community strategic planning process regards numbers only as a means of fully understanding the issues that then dominate the discussions in their meetings.

Strategic thinking ultimately means a very critical assessment of the direction of the community and its local government’s programs. Strategic thinking can prescribe major changes in some program areas, and it requires difficult decisions. It can also result in actions that, although correct and necessary, could be unpopular for some. Strategic planning—like local government leadership—is not for the faint of heart. The following statement on page 62 of the 1993 edition of this book is just as true today:

Business as usual is easy, and subsequent failures can be attributed to the mere continuation of past practices. But to risk the survival or success of entire programs, the welfare of constituents, and one’s reputation on decisions to move in new directions can require both personal and organizational courage.

Decision-making styles

The manner in which an organization makes decisions affects both the development of the strategic plan and its implementation (implementation is addressed at length beginning on page 45). The decision-making style of the local government can influence the process of strategic planning either positively or negatively.

Typical business organizations choose one of three decision-making styles— top-down, bottom-up, or group decision making—and apply it fairly consistently. However, few communities consistently use either top-down or bottom-up styles in their purest form. More likely, the style changes from instance to instance and from one individual to the next. Neither approach can be said to be universally correct.

Each style has general applicability to a variety of situations and may be the best method in a given location at a given time and for a given process. For a strategic planning exercise, it would be useful for the community’s leadership to consider each style and its relative advantages and disadvantages and then select one to promote as the style in which the process will be conducted. It would also be useful, however, for local leaders who are about to sponsor a strategic planning process to consider and discuss with all the participants the manner in which they would like to see the process proceed.

Top-down decision making

Top-down decision making begins, as the name implies, with the senior-most management person in the process. This can be the mayor, the council chair, or a strong executive. This style is generally successful when difficult decisions need to be made in an urgent fashion. It can be effective only if the leadership is respected and if those who must implement the decisions respond accordingly.

In strategic planning exercises that make use of top-down decision making, senior leadership usually drives the process by identifying the trends and issues to be considered. The leader may even go so far as to itemize options, in which case the planning exercise really becomes little more than a nonstrategic discussion of that individual’s ideas.

The top-down style does have some advantages for strategic planning, and the advantages are usually particularly apparent when the community is engaging in its first strategic planning exercise or when there is an abundance of new participants in the process. In these instances, the leadership can use an authority position to encourage the group to take a hard look at certain trends and help identify the difficult decision options that will arise in the future.

The top-down decision-making style appears to be most productive for local government strategic planning when a need exists for strong leadership and clear direction for the planning committee. This style needs to be exercised in a benign manner, however, so that participants are encouraged to consider every possibility within the context of their understanding of the future. There is a very fine line that, if crossed, could be damaging to the outcomes of the exercise.

Bottom-up decision making

In bottom-up decision making, concepts and trends analysis are filtered up from lower levels within the local government organization. Individuals who provide direct services and who manage the various processes of local government on a day-to-day basis help identify the issues that are important and the trends that need to be addressed in the environmental scanning phase of the process.

The clear advantage of this approach is that it solicits input from those who deal with a variety of issues on a regular basis. This is valuable intelligence for the ultimate decision makers. Another advantage is that it creates buy-in on the part of those who will ultimately implement the final decisions.

The bottom-up style seems to be more egalitarian, but it too has drawbacks. Elected officials and senior managers in a community are the ones who must live and die by the plan. If its components are found over time to be out of alignment with the reality of future conditions, it is they who must answer to the community.

Further, it is the group at the top that is most likely to have a broad view of both the issues at hand and the issues likely to arise in the future. Therefore, they must, at least to some extent, set the tone and provide overall direction. Further down in an organization, increasingly parochial interests in the issues under review are likely to appear, which can ultimately lead to concerns about protecting specific programs. This can potentially derail the process. In such cases, the plan becomes less strategic in nature and little more than a sum of programmatic parts.

Group decision making

The most common approach to decision making is a hybrid of the top-down and the bottom-up styles. In the literature, it may be referred to as team decision making or group decision making. Typically, it is conducted without being intentionally established; it simply evolves as the prevalent manner of operating.

Because strategic planning is important for providing a structure in which to identify and assess future issues that might not otherwise receive due consideration, the broader the representation of the planning committee, the greater the chance for group consideration of all matters of potential significance. And each issue will be reviewed in greater depth.

However, group decision-making styles have significant drawbacks. Some groups tend to feel increasingly secure in their decisions as their numbers increase, which can be an asset because it may enable the group to make the more difficult of the necessary decisions. It can also be dangerous, however, if the group subconsciously equates the inherent safety in its numbers with invulnerability. It may then accept assumptions that may not have been fully considered and evaluated. If they recognize that this tendency exists, groups can consciously work to avoid it.

One of the strengths of group decision making is that it is more likely than either of the other styles to incorporate into the discussions and analyses a wide variety of perspectives and ideas. As such, it can be seen as offering something for everyone. This may sound like an always positive outcome, but any conscious effort to ensure that there is something for everyone can result in making less-than-optimal decisions. Again, often the simple recognition of such possible tendencies is sufficient to help committee members avoid them. A brief review of the process to be used by the group for making decisions might prove to be a productive exercise.

One drawback to group decision making is that it usually slows the process because more people need to be heard and the potential for conflict is greater. Leadership needs to weigh the positive and negative aspects of each decision-making style and select the one that seems most likely to be successful in the particular situation.

What is the best group size to ensure the most effective communication? Much has been written on this topic, and various articles support numbers from six to twenty. The real number is likely to be different for every situation, every location, and every group of individuals. In some communities, a group considered by the literature to be of an ideal size may be too small to be inclusive enough. Careful review is needed before constituting and training the group.

Ethics

Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis wrote: “Honesty by itself is not enough. The appearance of integrity must be concomitant.” Public officials must keep this constantly in mind. Many who participate in the strategic planning process have specific and even fairly narrow areas of professional responsibility. They must table their parochial interests and approach the environmental scan, the identification of issues, and the development of goals and tactics with an eye on the best interests of the community rather than on their own, more narrow concerns.

An essential concern is the reality of ethical behavior and an approach that is the best for the community. Ethical behavior is not enough; also necessary is the stake-holders’ perception that the process was open, honest, and fair.

Human resource management

The staff of the local government potentially have two functions in the strategic planning process: input and implementation. During both of these, employees may reflect concern over changes that need to be made.

Moreover, many human resource functions—staffing requirements; position descriptions; recruitment and selection; promotions, demotions, and transfers; training and professional development; performance review; record keeping; wages and benefits issues; collective bargaining; safety issues; and federal regulations concerning employment and conditions—are affected by the process of strategic planning and the development and implementation of new community directions.

In addition, a vital contribution of the human resource department to the process and the implementation of the plan is the communications function. The more that can be done to keep staff apprised of the process and potential changes, the greater will be the buy-in by those who will implement the tactics laid out in the final plan.

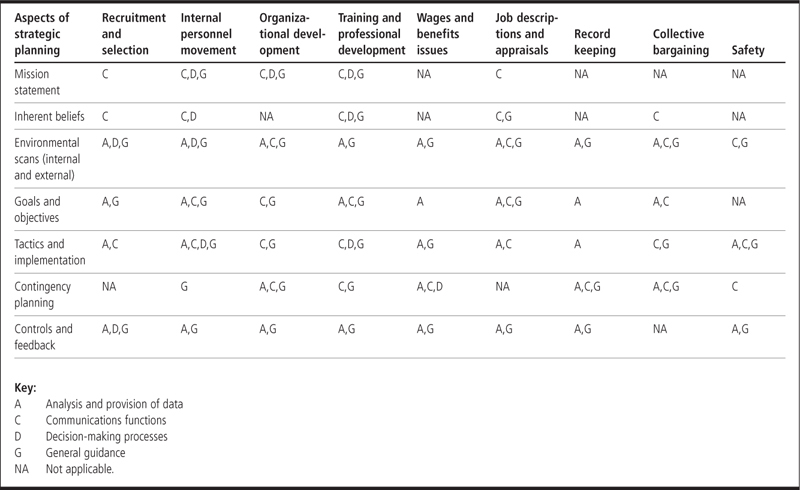

The human resource staff can support several functions that take place during the strategic planning process; these include data provision and analysis, forecasting and decision making, and providing general guidance to the planning committee. Table 3-1 shows the contributions that human resource managers can make in each part of the strategic planning process.

It is clear from the proliferation of Cs in Table 3-1 that the communications function is vital for strategic planning. As a critical conduit for communications to employees, the role of human resources begins with the onset of the process.

Table 3-1 How the human resource function contributes to the strategic planning process

Employees must be aware of what is expected and why the process is taking place. They must be kept apprised of the progress made by the planning committees, and they must understand what it means for them and for the programs and services they administer.

As programmatic changes are planned, staff may have to be retrained. For example, a strategy that applies technology to previously manual functions may require computer skills to be upgraded. New community outreach efforts may be more successful if staff are trained in public speaking and other communication skills. Gaps in the existing complement of skills and new skills required by new programmatic directions must be identified and addressed.

As elements of the strategic plan are finalized, staff should be advised. Staff’s firm understanding of the discussions that led to a revision in the mission statement or the stated core beliefs of a community will lay the foundation for a more firm appreciation of the goals, objectives, action plans, and individual assignments. There is a direct relationship between the extent to which the components of the plan are understood and accepted by staff and the success of the plan.

Record keeping and data analysis are often functions performed by human resource departments. Staffing requirements and performance effectiveness indicate to managers which programs are successful and which employees are most productive. Together with the reasons for such performance outcomes, such data are valuable intelligence for planners who must decide which programs to keep or eliminate, which to expand or minimize, and which to redesign.

As programs, staffing requirements, and assignments change, decisions about reassignments, promotions and demotions, performance measures, and compensation might also have to be made. In some municipalities, human resource professionals may be required to reconsider collective bargaining agreements and employee contracts.

Every component of the strategic planning process could include a role for the human resource manager. The vision for the community and the mission statement for the organization need to be fully understood and serve as the basis for what staff do and why they do it. As staff perform even the most mundane tasks, they must understand why they are doing so. Cleaning a park is more than merely picking up refuse; it is one means of providing the best service possible for tax dollars paid and of improving the quality of life for the residents of the community.

In some communities the human resource director might be a resource for the planning committee, but in others the director could be an active participant in the process. In either case, the range of functions for which human resources is responsible has to be represented and supported.