We often think of America in the late 1950s as a drab, dreary, and uninspiring place. Gray was the dominant color, politics were largely conservative, the great move to suburban cookie-cutter housing was in full swing, fast-food chains were on the rise, and television was the new entertainment medium of choice. The nation appeared to be moving toward a consensus culture: one grand, homogeneous wasteland with a Howard Johnson’s, Holiday Inn, and McDonald’s at every freeway exit.

In hindsight, it is obvious that, although all of these forces were undeniably in effect, their combined impact was not as overwhelming as we might believe. Moreover this cultural homogenization was not evenly distributed throughout the country, Memphis, Tennessee, in particular, seemed largely unaffected by these developments. Even today, as we near the close of the twentieth century, parts of Memphis seem to be little different from what they were at the end of World War II.

Memphis had always been a land apart. Majestically perched on a bluff on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River, in terms of cartography Memphis is situated in the south-west corner of Tennessee; in terms of culture, Memphis has long been symbolically viewed as the capital of Mississippi. While Tennessee is a land of rolling hills and genteel country music, Memphis is as flat as the Delta and has historically served as a fertile breeding ground for blues, jug bands, black gospel, and rockabilly. The differences between Memphis and the rest of Tennessee are those that separate night from day.

Claiming more churches per person than any other city in the Union, Memphis has long served as a magnet for anyone who grew up within a two- or three-hundred-mile radius and had dreams bigger than a cotton field. The city also served as a stopping-off point for whites and blacks participating in the great migration north to St. Louis or Chicago. Many such migrants put down roots in Memphis and never left.

Despite such growth, Memphis in the late 1950s remained underdeveloped, backward, insular, and reactionary. Urban by definition, the city was rural in terms of mind-set and, although not completely impervious to national developments, it tended to march to a drummer of its own. How else can you explain Gus Cannon, Rev. Robert Wilkins, Ike Turner, Howlin’ Wolf, Mattie Wigley, Sam Phillips, or Elvis Presley? Significantly, none of these cultural icons was actually born in Memphis. Rather, each in his or her own way migrated to the Bluff City, attracted by the bright lights and what in relative terms must have appeared to be economic and cultural opportunity.

For most of the twentieth century, Memphis has been a vibrant musical center, nurturing and supporting more musical genres than perhaps any other city in the United States. The home base of the Church of God in Christ, Memphis has long been a center for the recording of some of the most intense Pentecostal music-making imaginable. In the 1920s and 1930s, the city also served as a common site for the recording of country blues and jug-band music, and for a brief period was home to famed blues composer and society dance band leader W. C. Handy. Shortly thereafter, Memphis produced, in Rev. Herbert Brewster and Lucy Campbell, two of the most important gospel composers of all time. In the postwar era, the urbanized, sophisticated, big-band blues of B. B. King stood side by side with the harsh city-meets-the-country proto-metal of Howlin’ Wolf and the newly emergent shouting gospel quartet style of the Spirit of Memphis and Southern Wonders. With the emergence of rockabilly in the mid-1950s, Memphis music stood poised at the root of a worldwide cataclysm. Finally, in the 1960s and 1970s, with Stax, Goldwax, and Hi Records, Memphis served up what is arguably the richest soul music the world has ever known.

There was obviously never a shortage of music in the city, much of it made by iconoclasts who simply wouldn’t have had a chance in most other more “sophisticated” or “developed” music centers. Significantly, there were also a cast of what we might think of as facilitators, people who were often as colorful and very nearly as important as the musicians themselves, such as Nat D. Williams, Dewey Phillips, Martha Jean Steinberg, and Sam Phillips. Beginning in 1948, Williams and then in 1954 Steinberg helped pioneer the emergence of black radio via the legendary WDIA, “the mother station of the Negro.” Across town, both figuratively and literally, Dewey Phillips was as close as a white guy could get to the hepness and cool and visceral energy that radiated from the black music he chose to program nightly on WHBQ. All three of these individuals figure into the Stax story, influencing and/or promoting the odd amalgam of black and white musical cross-pollination that lay at the bedrock of Stax.

Sam Phillips, on the other hand, had all but withdrawn from the record industry by the time Satellite Records, the precursor to Stax, came into fruition. As the essentially one-man operator of Sun Records, Phillips had recorded a Who’s Who of black and white mid-South-based artists, including Howlin’ Wolf, B. B. King, Ike Turner, Jackie Brenston, Little Milton, Junior Parker, Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis, Roy Orbison, Carl Perkins, and Charlie Rich. Collectively, this cavalcade of stars simply changed the very rules of American music-making.

A musical milieu populated by these musicians and facilitators must have been mind-boggling to behold. For Memphians in the know, each day must have seemed infinitely bright, with each new record seeming to hold the very possibility of self-definition and/or reinvention. One of the promises this music communicated was that anything was possible, the game was wide open. No one (at least that was the myth) had to be constrained by his or her position at birth. Consequently, thousands were bitten by the music-making bug, including the man most responsible for this story, James F. Stewart.

In 1957 the demure Stewart was a bank teller by vocation and a country fiddler by avocation. Not too surprisingly, the reality for Stewart was that the latter was much more interesting than the former. However, as much as he might have wanted to be, it was clear that he was not destined for fame or fortune as a practicing musician. But, what about this Sam Phillips guy? As far as Stewart knew, Phillips couldn’t play an instrument at all. Maybe there was more than one way to crack this nut. “I never really became a proficient or professional musician,” mused Stewart, nearly three decades after the fact. “I knew I was not gonna be able to make it in that field. I just didn’t have the ability. [Starting a record company] was like another way of being involved in the music business so to speak. It was like if I can’t be a singer or a musician, maybe I can make a record. Not produce a record, because I didn’t know what a producer was. That was a term that was completely unknown then. I wanted to make a record.”

Born July 29, 1930, about seventy miles east of Memphis near the Mississippi border in the farming community of Middleton, Tennessee (population around 800), Stewart grew up intoxicated by postwar country music. His parents, Ollie and Dexter Stewart, ran a farm, with Dexter supplementing the family income with carpentry and bricklaying work. When Stewart was ten, his daddy bought him a guitar. “I didn’t really care that much about it,” recalls Jim. “Then he bought me a three-quarter-size violin and I got really interested. On Saturday night I would turn the radio on to the Grand Ole Opry and I’d try to play along with it.” Practicing constantly when he wasn’t in the field working, Stewart learned by ear and eventually developed enough facility that he and a friend were able to form a band that regularly provided the entertainment at square dances in that part of the country.

Once finished with school, there was little to keep a budding musician in Middleton, and so, at age eighteen, he headed for the big city an hour-and-a-half down the road, hoping to further develop his career as a country fiddler. Heavily influenced by the Western Swing of Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys, Spade Cooley, Pee Wee King, and Tex Williams, as well as by the honky-tonk sounds of Hank Williams, Moon Mullican, and Ernest Tubb, Stewart picked up the odd playing job around town while working for Sears Roebuck during the day. Prior to WDIA switching to an all-black format, Stewart could also be heard on that legendary station, regularly playing his fiddle in the early morning hours of the day as a member of Don Powell’s Canyon Cowboys.1

By late 1950 Stewart had moved into banking with First National Bank (now First Tennessee Bank) only to be drafted in the new year into the armed forces. In 1953, following the requisite two-year term, Stewart returned to the bank and got a job playing in the house band at the Eagle’s Nest out on Lamar Avenue. When Stewart was still in the house band, Elvis Presley would often play during the intermissions at the club. “I got interested in recording then as Elvis got to be a giant,” recalls Stewart. At the same time as this new interest was taking shape, Stewart took advantage of the GI Bill and got his B.A. degree at Memphis State University (now the University of Memphis), majoring in business management and minoring in music.

By 1957 Stewart’s interest in recording led him to tape a couple of songs which he then attempted to take to Sun as well as to a few other local record companies. With the exception of Erwin Ellis, Stewart’s barber, who also happened to own a small concern dubbed Erwin Records, nobody would give Stewart the time of day. Ellis loaned Stewart his first recording equipment, educated him about the value of publishing, and taught Stewart the basic mechanics of running a small independent record label and establishing an affiliated publishing company.

Undaunted by the lack of interest everyone else exhibited towards his recording efforts, under Ellis’s guidance Stewart started a label and recorded two sides by local country disc jockey, bass player, and singer Fred Byler.2 Issued as Satellite 1003 in January 1958, Byler’s recording of “Blue Roses” b/w “Give Me Your Love” was an inauspicious debut.

House band at the Eagle’s Nest: (left to right) Jim Stewart, Speedy NcNatt, Joe Bracciante, WHHM disc jockey Sleepy-Eyed John Lepley, Ed Morgan, Tiny Dixon, Dan McHugh, Hugh Jeffreys, Thurmon Enlow, Ginnie Ford, COURTESY HUGH JEFFREYS.

At the time of its release Stewart was an equal partner in the new label with Byler and a rhythm guitarist named Neil Herbert, as all three had put in three or four hundred dollars of start-up capital. In total, they probably pressed less than three hundred copies of the Byler record.4 The record is best described as undistinguished. Stewart wrote the A-side (his only composition ever to be recorded), which Byler croons his way through in a style somewhat reminiscent of Jim Reeves. The backing track is dominated by a weak and weepy imitation of the Anita Kerr Singers5 and a somewhat heavy-handed sock rhythm backbeat. Virtually no copies were sold as, according to Jim, the only play the record received was on KWEM, the station where Byler worked.

Satellite’s next release came within the month. This time Stewart was much more successful aesthetically, if not commercially. Neil Herbert brought rockabilly singer Don Willis to the label, and Stewart recorded him on one of the all-time killer rockabilly records. To this day “Boppin’ High School Baby” backed with “Warrior Sam” (Satellite 101) remains a much sought-after collector’s item in Europe.

After the Byler and Willis 45s, Stewart recorded and Satellite released a couple of undistinguished (Stewart describes them as “washed-out pop”) country-pop records by Donna Rae and the Sunbeams (103) and Ray Scott (104), both most likely issued in 1958.6 Donna Rae was the hostess of Wink Martindale’s popular Memphis teen television show, “Dance Party.” Erwin Ellis introduced Jim to Chips Moman, who played lead guitar on Donna Rae’s record. Chips, in turn, was responsible for soliciting Ray Scott, in whose band Chips often played, to pen both sides for Donna Rae.7 Scott then cut a deal with Stewart where he would hire the musicians, pay for the pressing of his own record, and give Stewart the publishing if Stewart would provide the studio and engineering duties free of charge. Scott’s band included noted Memphis musicians Gene Chrisman on drums and Lee Adkins on lead guitar. As with the first two Satellite releases, Stewart pressed a few hundred copies of the Donna Rae and Ray Scott 45s (Scott is quite sure that only 300 were pressed of his record), selling somewhere between one and two hundred of each. “I couldn’t get the stores to stock them,” laments the then-frustrated entrepreneur.

Stewart, Byler, and Herbert had been recording Satellite’s releases in Stewart’s wife’s uncle’s two-car garage on Orchi Street8 using a portable reel-to-reel tape recorder owned by Erwin Ellis. However, Stewart wanted to buy a state-of-the-art Ampex 350 monaural tape recorder—which at the time cost $1,300—but the partners lacked the needed capital to make the purchase. Stewart appealed to his sister, Estelle Axton, for help, asking her to mortgage her house for what he remembers as eight or nine thousand dollars.9

Axton was intrigued. For a while now, she had wanted to be involved with something other than her current job at the bank. At the same time she had the unenviable job of convincing her husband, Everett, that mortgaging the seventeen years of equity they had built up in their house to finance a recording label that had heretofore enjoyed absolutely no success somehow made sense. At the time, Everett Axton was only making eighteen dollars a week, their house note was already twenty-one dollars a month, and they had two teenagers still living at home. Nonetheless, in due time Estelle wore Everett down and they took out a second mortgage that was used to buy out Herbert and Byler’s original investment, to finance the purchase of the Ampex tape recorder, and to provide badly needed operating capital.

Twelve years older than Jim (a sister, Lucille, had been born in-between), Estelle Stewart had always been strongly interested in music. As a teenager she had been a fan of pop music and had played the organ and sung soprano in a family gospel quartet. First coming to Memphis in 1935 to get her teaching certificate—teaching being the only career at the time readily open to women—she met her husband-to-be, Everett Axton, while attending Memphis State University. Teaching certificate in hand, Estelle went back to Middleton where, ironically, her younger brother Jim was one of her students. In 1941 Estelle married Everett and moved back to Memphis. For nearly a decade Estelle stayed at home raising two children, reentering the workforce in 1950 as an employee of Union Planters National Bank. She would remain at Union Planters until 1961 when she opened the Satellite Record Shop.

Estelle recalls being attracted to the record industry because she liked the idea of working with younger people. With Jim in charge of the recording end of the business, Estelle got busy augmenting Satellite’s income by buying records wholesale from a local One-Stop10 distributor in Memphis, which she would then resell at a mark-up to people she worked with, neighbors, and anyone else who might possibly be interested. Over the next few years, she would take this activity several steps further.

With the acquisition of new equipment, Stewart and Axton needed a permanent place to record other than a garage. As fate would have it, a barber friend of Stewart’s by the name of Jimmy Mitchell had a vacant store building about thirty miles outside of Memphis in Brunswick, Tennessee. Mitchell was a country-and-western freak and was happy to let Stewart and Axton use his building free of charge until they made a profit if, in return, they would make a record with his daughter. At this point no one remembers who his daughter was but, evidently, although some effort was expended attempting to record her, she was not good enough to gain a record release.

In the late 1950s Brunswick was a sleepy rural enclave. Not surprisingly, the locals were pretty suspicious of this new-fangled enterprise called Satellite Records. As Stewart recalls events, he and Estelle were summoned to a town meeting at the local church. “Some of the local townspeople did not really understand what a recording studio was all about. They didn’t know if it was legal, if it was a business, or what kind of business. They wanted to know more about us. You have to remember this is rural, it’s southern, and it’s a very close-knit community. They didn’t understand why a recording studio would come to Brunswick. We had to answer a lot of questions, explain who we were and what making a record was all about.”

Once the townspeople were satisfied, Jim and Estelle—with help from Chips Moman and a bass-playing compadre named Jimbo Hale—proceeded to set up shop. Ever resourceful, Stewart’s wife, Evelyn, established a malt shop in a small adjoining structure that she operated on the weekends to help defray expenses. The studio itself was about as bad as it got. Mitchell’s store was little more than a long wooden frame building.11 The space was already divided at the two-thirds mark, so Stewart put a little window in the partition allowing the former storeroom at the back to serve as the control room, housing Satellite’s newly purchased Ampex recorder and mixers. Equipped with eight inputs (seven used for microphones and one for echo) all of which went straight to one channel, in Jim Stewart’s words, “it was the best machine we could get at the time.”

The equipment may have been halfway decent but the studio was something else again, housing a Silvertone amplifier and little more. No acoustical work of any kind was done to this section of the building, aside from hanging a kind of burlap on the walls. “It was a horrible studio,” admits Stewart. “I mean horrible! It was totally empty with wooden floors and the sound bounced all over the place. It had so much reverb it would go on forever.” Further complicating matters was the fact that within thirty or forty yards of the nascent studio lay a railroad track. Trains blew by about every three hours, halting sessions and more than once ruining a recording.

In the spring of 1959 while still in Brunswick, Stewart recorded his first black group, the Veltones. Samuel Jones, Alvin Standard, Kenneth Patterson, George Powell, and Jimmy Ellis12 had sung in and around Memphis since 1952, for eight years enjoying a residency at Curry’s Club Tropicana with the Ben Branch Band. Stewart does not precisely remember how a country fiddler, who he freely admits did not know the first thing about rhythm and blues, came into contact with the group. He is reasonably certain that one Earl Cage, who would later surface as a songwriter on one side of the first release on Goldwax Records, was somehow involved, and has vague recollections that, via Cage, he had already attempted recording a black group by the name of the Keytones. According to Chips Moman, “Earl Cage was in and out of every studio in town all the time. He would always have somebody that could sing or somebody that he was pitching. He was into everything and never did really get nothing going.” All Veltone members Sam Jones and Alvin Standard can recall is that it was Jim who contacted them.

In any event, after a month of biweekly journeys out to Brunswick, the Veltones’ “Fool in Love” backed with “Someday” was deemed ready to release. The A-side of the Veltones record was cowritten and produced by session guitarist Chips Moman with Jimbo Hale on bass and Jerry “Satch” Arnold on drums. It would provide Stewart with his first hint of the possibility of success. Released in the summer of 1959 as the second record to bear the number Satellite 100, in September it was picked up for national distribution by Mercury Records for an advance somewhere in the neighborhood of four or five hundred dollars. “I thought that was a major coup at the time,” muses Jim. “That was the first real money we made in the record business.” Unfortunately, the Veltones were not to have their day in the sun and the record stiffed. Stewart received not a further penny from Mercury and found himself back at the drawing board.

After a year in Brunswick and only two record releases (the Veltones record and Charles Heinz’s “Prove Your Love” b/w “Destiny”—Satellite 101—the latter artist brought to the company by Moman and Hale with accompaniment provided again courtesy of Moman, Hale, and Arnold), Stewart realized the neophyte operation had to make a move. “Brunswick was way out of the city. It was isolated and it was very inconvenient. We couldn’t attract any artists because it was too far away from the center of the city. We decided we had to move back into town and either get very serious about the business or get out of it.”

By early 1960, Stewart and Axton had given up on Brunswick and begun a search for a suitable location back in town. Acoustics and affordability being their two primary concerns, the would-be entrepreneurs quickly decided that the two types of buildings that might be most suitable were an old church or one of the old neighborhood movie theaters that had been abandoned in the late 1950s. Both types of facility would have the high ceiling and general room size that Stewart thought so acoustically desirable.

The first location that they looked at seriously was the old Capitol Theatre located at the corner of College and McLemore.13 Owned by Paul Zerilla, the Capitol, as was the case with most of the city’s neighborhood movie theaters, had been supplanted by the new, more modern movie palaces downtown.14 Consequently, by 1960 it had been relegated to little more than hosting the occasional country-and-western performance (Jimbo Hale remembers both Mel Tillis and Eddie Bond being among the featured attractions); and as the neighborhood began to shift from white to black, even the country rentals had begun to fall off. According to Chips Moman, it was he and songwriting friend Paul Richey who found the theater while deliberately scouring black neighborhoods looking for a suitable building. “I wanted it in a black community,” claims Moman. “That’s the music that I wanted to do.”

The fledgling owners of Satellite Records leased the Capitol for what Stewart remembers as $150 a month.15 Given the fact that Stewart was only making about $350 a month at First National Bank and that Satellite was bringing in no income, this was no trifling amount. Estelle immediately came up with the bright idea that they would generate at least some cash flow if they could convert the candy counter of the theater into a record shop. With the lobby serving as display space for the LPs, the Satellite Record Shop was born. The record store would prove important in a number of respects.

The lease signed, Jim, Chips, Everett Axton, Estelle’s son Packy, and Jim’s wife set about renovating the theater. The most onerous task, pulling the seats out, had already been taken care of by Zerilla as part of the lease agreement. The rest of the work took a couple of months. Everyone pitched in after their regular workday and on weekends, hanging acoustical drapes (handmade by Estelle), building a control room on the stage, putting a few carpets on the floor, building baffles with burlap and ruffle insulation on the one outside plaster wall to cut down on the echo, and building a drum stand. The only thing professionals were hired to do was to hang the baffles from the ceiling.

Even with all this work, 926 E. McLemore remained a very “live” recording environment, having a reverberation effect akin to that of a concert hall. This would be an important component of what eventually became known as the Stax sound. Perhaps the oddest thing about the studio was that the original theater’s sloping floor was never leveled. “I wasn’t going to spend the money to level the damn floor,” exclaims Stewart. “We didn’t have the money to do those things.” In typical Stax happenstance fashion, not leveling the floor turned out to be an acoustical plus as it meant the studio had no surfaces that were directly opposite each other.

In addition to all this acoustical work, a zigzag false partition was constructed that divided the theater in half, because, to put it mildly, the building was enormous. At its highest point, the ceiling was twenty-five feet high and, even when cut in half, the studio measured forty by forty-five feet.

Although the renovations cost a grand total of between two and three hundred dollars, Stewart and Axton found themselves strapped for funds. In a move that could have decidedly changed this whole story, they tried to find local investors but were unsuccessful. Consequently, according to Axton, she refinanced her house one more time to get another four thousand dollars of badly needed operating capital. As luck would have it, their very next recording would provide them with their first hit.

Although the Veltones recording was ultimately not a commercial success, the fact that it was an R&B record with a bit of potential led Stewart to make promotional visits to all the local black media. No outlet was as important as WDIA where, among others, Stewart came into contact with one hepcat of a disc jockey named Rufus Thomas. If not a local legend by this point, Thomas was certainly part of the Who’s Who of Memphis’s black community. Married by Aretha Franklin’s father, Reverend C. L. Franklin, Thomas’s career had been long and varied, encompassing work as a dancer, comedian, emcee, vocalist, and radio announcer. One of his earliest gigs was as part of the dance team “Rufus and Johnny” with the Rabbit Foot Minstrels. He later forged a distinguished career as a comic (“Rufus and Bones”) and master of ceremonies at all the black theaters in Memphis, including the Handy, Harlem, Savoy, Hyde Park, and, most significantly, the Palace. Most important as far as Stewart was concerned, in addition to hosting the daily “Sepia Swing Club” and “Hoot ‘n’ Holler” shows on ’DIA, Thomas was a singer and songwriter who had recorded for Star Talent, Meteor, Chess, and, most notably, Sun Records going back to 1949. His most successful recording had been an answer song conceived as a response to Big Mama Thornton’s R&B hit “Hound Dog.” Entitled “Bear Cat” and released in 1953, the record had been Sun’s first bona fide hit, peaking at number 3 on Billboard’s R&B Best Seller and Juke Box charts.

When Thomas drove down to Satellite’s new studio on McLemore he hadn’t really made the connection that he would be seeing the same guy who brought him the Veltones’ record. Instead, he had been prompted by a friend of his, a pianist named Bob Talley, who had already ventured into the theater, made Stewart’s acquaintance, and felt that there were some possibilities here. Thomas eventually took tapes of himself, his daughter Carla, and a duet they had sung together down to the new studio. Stewart suggested he would be interested in recording the latter.

Thus, Rufus and Carla Thomas became the first artists recorded at the newly renovated theater-cum-studio. Issued in late summer 1960 as Satellite 102 under the sobriquet “Carla and Rufus,” “Cause I Love You” b/w “Deep Down Inside” (the latter written by Rufus in the studio) changed the lives of everyone concerned. The recording, as with all of Stewart and Axton’s previous efforts, was a nonunion session, because they simply could not afford to pay union rates.16 Among those who gladly accepted the lower fee were a sixteen-year-old Booker T. Jones on baritone sax, Rufus’s son Marvell Thomas on piano, and Wilbur Steinberg on bass. Collectively they conjured up a jumping New Orleans-influenced rhythm that Steinberg claims was his idea, and was borrowed from New Orleans artist Jesse Hill’s recently released Top 5 R&B and Top 30 pop hit “Ooh Poo Pah Doo.”

After three years of plugging without “even a smell of a hit,” Jim Stewart suddenly found that he had a successful record. “We put that record out,” Stewart remembered, smiling, “and it was like, surprise! People [were] actually buying this record and we weren’t having to give them away. It was a great feeling. I really felt like I was in the record business. I had actually done something that the public was buying.”

The success of “Cause I Love You” could not have been more timely because, by this point, Estelle’s money was rapidly evaporating and, aside from the record shop, there was absolutely no money coming in. In addition to providing much-needed cash flow, “Cause I Love You” also provided direction. Although half of the next eight Satellite releases were either pop or country, for Jim Stewart life had irrevocably changed. As he himself puts it, “Prior to that I had no knowledge of what black music was about. Never heard black music and never even had an inkling of what it was all about. It was like a blind man who suddenly gained his sight. You don’t want to go back, you don’t even look back. It just never occurred to me [to keep recording country or pop].” From that moment on, Satellite became a rhythm and blues label.

The label benefited from a number of fortuitous circumstances with regard to this newfound direction. Perhaps the most important was the fact that Satellite’s studio was located in the heart of what was fast becoming a black ghetto. Significantly, Satellite’s first salaried songwriter, David Porter, worked at the Jones’ Big D grocery right across the street from the studio. Two other early arrivals, Booker T. Jones and saxophonist Gilbert Caple also lived in the neighborhood.17 Similar stories abound with regard to the arrival of other Satellite/Stax singers, instrumentalists, songwriters, producers, engineers, and office staff. Stax was an integral part of the community and, conversely, much of what became the heart of Stax came straight out of that same community.

The record store also played a key role in aiding and abetting neighborhood relations. One of the hipper local hangouts, the store also served as a conduit for talent recruitment, a number of future session musicians, songwriters, and vocalists making their initial contact with the company via the store. Among the customers was keyboardist and namesake of Booker T. and the MG’s, Booker T. Jones. “I think there would have been no Stax Records without the Satellite Record Shop,” declares Booker. “Estelle Axton will tell you we all came in there. Every Saturday I was at the Satellite Record Shop [and] that’s where I went after school. After I threw my papers that’s where I hung out. It was important to me as a young kid. I got to go in there and listen to everything. I’d spend three hours in the evening in there. I maybe bought one record a week, just enough so they’d let me back in. I’d hear that music behind the curtain so I just kind of hung around there. It was an important influence.” Chips Moman recalls seeing Booker at the shop on a number of occasions, fresh out of school in his ROTC uniform.18

Although future MG Duck Dunn was white and consequently did not live in the neighborhood, the Satellite Record Shop was similarly important for him. “I used to live out east,” relates Duck. “We had a little record shop there but if you wanted a rhythm and blues record, you had to special order it and it would take a week. Or, you’d have to get on a bus and go down to Beale Street to the Home of the Blues Record Shop. But they’d run you out if you [just] wanted to look.”

“They wouldn’t let you browse,” adds MG guitarist and early Satellite clerk Steve Cropper. “Satellite was not that way. Estelle was very trusting of the people that came in and she’d let people browse. If they wanted to hear anything, we’d play it and let them hear it. They didn’t have to buy it if they didn’t want to. It was also amazing [in that] the local people who came by the record shop, they’d go, ‘I write songs or I sing.’ And we used to listen to them. It was good for everybody to have that sort of relationship with the people who lived around there.” A number of future Stax employees, including Steve Cropper, Deanie Parker, Homer Banks, James Cross, William Brown, Johnny Keyes, and Henry Bush, started out as counter help in the record store. By 1961, its success inspired Stewart and Axton to expand their retail activity beyond the candy area at the front of the theater. Axton quit the bank to run the store on a full-time basis and they rented the recently vacated King’s Barbershop next door. This was to serve as the home of the Satellite Record Shop through May 1968.

In addition to serving as a recruitment center and fostering neighborhood relations, the store also provided a vehicle for staying current with the listening tastes of Memphis black youth, providing a ready-made test market for just-cut Stax releases. It was not uncommon for Axton to take songs that had just been recorded and play them in the record shop for the local populace; many were changed, and some were not released, depending on their reaction. Even in the case of already-released product, the opinion of local youngsters could inform Stewart and Axton whether a record had a chance of becoming a hit, and consequently would be worth the hefty promotion expenses and the pressing of large quantities of records. Presumably a lot of money, time, and energy were saved by this method. “I gained a lot of knowledge from that,” testifies Stewart. “A lot of record executives in their ivory towers could come down into a record shop and work on Saturday night in the ghetto behind the counter and learn a hell of a lot about the record business. That was the best test market in the world. We literally took demos up there, put them on the turntable, and watched the reaction.” Atlantic Records co-owner and future Stax distributor Jerry Wexler was suitably impressed. “The theater on McLemore, the little store they had, the way they interacted with the street … I thought that was great.”

The Satellite Record Shop had at least two other functions. It provided immediate access to a library of sounds whenever anyone cutting a session or writing a song needed to hear something currently out on the market. This proved useful for any number of Booker T. and the MG’s covers, as well as at least Otis Redding’s covers of “Satisfaction” and “Try a Little Tenderness” and Steve Cropper’s writing of “(In the) Midnight Hour.” Perhaps even more important, for aspiring writers the store functioned, in Estelle word’s, as a workshop of sorts. “When a record would hit on another label,” explains Estelle, “we would discuss what makes this record sell. We analyzed it. That’s how the writers in the Stax studio got lessons from the record shop. That’s why we had so many good writers. They knew what would sell. It was the workshop for Stax Records.”

Booker T. concurs: “Most all our musical ideas and influences came out of that little record shop in the first couple of years. The Ray Charles records we listened to, the Bill Justis records … they had all that there. I can’t see Stax being what it was without the Satellite Record Shop and Estelle Axton saying ‘Why don’t you guys try something like this?’ She was always doing that. We’d leave the studio and go up there and stand around. I’d be listening to Motown up there. It was like having a library right next to the studio.”

Eventually, the Satellite Record Shop became a Billboard reporting store, meaning every week Axton listed her best-selling records, which Billboard then used, along with similar reports from other stores around the country, to compile their rhythm and blues charts. Not surprisingly, Estelle routinely boosted the position of records released by Stax. Being extremely enterprising, Estelle also did local promotion for other record companies in exchange for free product that she would then sell in the store. She also bought and sold the free goods that local disc jockeys regularly received in exchange for radio play from other record companies.

All of Satellite’s releases up to this point were distributed by Buster Williams’s Memphis-based Music Sales. In addition to his distribution company, Williams owned a local record-pressing facility, Plastic Products, where Stewart had all of Satellite’s pressing done. Williams’s companies also pressed and distributed Atlantic Records product for the mid-South region.

The record industry at the time functioned much like the food chain. Larger independent record companies often picked up the distribution of a potential hit from smaller, more local concerns. Atlantic proved to be especially assiduous at discovering small labels to distribute. When “Cause I Love You” had sold about five thousand copies in the Memphis area (and according to Estelle another five thousand in Nashville and Atlanta), either Buster Williams, or his employee Norman Reuben, picked up the phone and hipped Jerry Wexler to the record.19 Wexler was impressed (“I liked everything about it that bespoke Memphis”) and, in turn, sent one of Atlantic’s promotion men into Memphis to talk to Jim about the possibility of leasing the master. As Satellite was in no position to even begin to afford to market the record nationally, Jim was more than interested. Soon after, Wexler himself called Jim Stewart, the net result being that—for what Jim remembers as a $5,000 advance—Atlantic got a master lease agreement for all future Rufus and Carla Thomas discs. “Cause I Love You” was repressed on Atlantic’s pop-oriented subsidiary Atco Records (Atco 6177).20

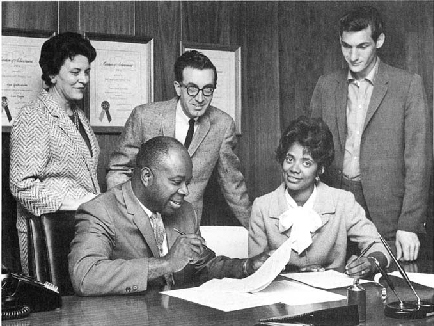

Contract singing: (standing) Estell Axton, Jim Stewart, Steve Cropper (seated) Rufus Thomas, Carla Thomas. COURTESY API PHOTOGRAPHERS INC.

The original signed contract with Atlantic covered only Rufus and Carla Thomas records. A couple of months later, via a handshake deal, Atlantic acquired first refusal rights on the distribution of any subsequent Satellite and later Stax release.21 “It was a good working relationship,” muses Stewart. “It was good for me because the label was in its early stage and I didn’t have the staff to do the promotion and marketing. I was more concerned with the creative aspect of the business. I had to be developing artists and the publishing.” “The essence of the deal,” recalls Wexler, “was that they delivered the master tapes at no cost. They paid for the sessions and handed us the tape, and we took the expense from there on—mastering, pressing, labels, jackets, distribution, promotion. It was a low royalty rate, I’ll give you that.22 I made the best deal I could, [but] there were never any charges against them.”

Atlantic had very little input into the creative side of the business. “It was very autonomous artistically at Stax,” says Wexler. “They did what they needed to do.” Jim Stewart concurs. “Atlantic had no input whatsoever. We cut the stuff and sent it to them. They really didn’t try to restrict us, nor did they control the timing of our releases.”

The Satellite/Atlantic relationship paid immediate dividends for all concerned. Now channeled through Atlantic’s distribution, “Cause I Love You” went on to sell another thirty or forty thousand copies, being especially strong in the Oakland area. To paraphrase Peter Guralnick, “the little label that could” was off and running.

1. Not “Don Paul,” as has been previously printed.

2. Stewart was not involved in the Jaxon label as has been printed a number of times over the years.

3. Stewart hated the name Satellite, but with the Russian satellite Sputnik the latest rage and no better ideas forthcoming, he finally agreed to it.

4. Until 1986, although Jim referred to it in a couple of interviews, its existence had never been confirmed because no copy had ever been found. That summer a single copy turned up in the back of a Memphis warehouse. More recently a second copy was discovered which is currently housed in the Memphis Music Museum.

5. Referred to as the Tunetts (sic) on the record label.

6. Although no one can remember why at this late date, there was never a Satellite 102 issued.

7. Rockabilly fans will be interested in knowing that this is the same Ray Scott who wrote Billy Lee Riley’s manic “Flyin’ Saucers Rock and Roll,” released a year earlier on Sun Records.

8. Not “Orchard Street” as has been previously printed.

9. Estelle believes she contributed $2,500 at this point and another $4,000 in 1961. She also believes that she came into the company in February 1958, after the Byler and Willis releases, not in early 1959. (In an interview in Goldmine magazine in 1979, Wilis stated that Estelle was involved with the company at the time of his recording.) However, the fact that Satellite’s numbering system was begun again in 1959 with the company’s fifth release, the Veltones’ “Fool in Love,” suggests that something significant happened after the first four records were issued, such as a partnership change. In addition, Stewart is quite certain that the Veltones’ release was the first record cut with the new equipment that was purchased with the money Estelle brought into the company. Therefore, it seems most likely that Estelle joined the fold in February 1959 rather than February 1958.

10. A One-Stop is a distributor that offers records from various labels at a discount to stores; the store owner can buy everything he or she needs from one place.

11. In 1994 Jim and I went out to Brunswick as part of the shooting of the film The Soul of Stax. This was the first time Jim had made the trek since 1960. The Satellite building was gone, but pretty well everything else, including the sign on the combination general store/cafe/post office across the street, remained the same.

12. The Veltones had recorded a couple of demos at Sun in 1958 that would remain unissued until the 1980s, they recorded as the Canes on Stax in 1962, and in 1966, they would cut two sides for Goldwax Records. In my liner notes to both The Complete Stax/Volt Singles 1959-1968 and 4000 Volts of Stax and Satellite I list the personnel for the Veltones as Samuel Jones, Willie Mull, Alvin Standard, and George Reed. At the time I wrote those notes I had been unable to locate any of the Veltones and this information was obtained from the files of Goldwax Records. In April 1996 I finally tracked down Samuel Jones and Alvin Standard, from whom I got the information printed here. Apparently Mull and Reed replaced Patterson, Powell, and Ellis sometime after the Canes record. In the same two sets of liner notes I indicated that Don Bryant thought that the Canes record was another Memphis group, the Largoes, recording under a different name. It turns out the Canes were the Veltones recording during a period in which they were managed by Dick “Cane” Cole.

13. Before deciding on the Capitol, the principals in Satellite had also looked at the Handy Theatre on Park just east of Airways and the Lamar Theatre, still standing on Lamar a bit west of McLean.

14. Zerilla also owned the New and Old Daisy Theaters on Beale.

15. Axton says $100; Moman thinks $75.

16. At the time union scale in Memphis was $51 per man for a three-song session with the leader being paid double. Satellite could only pay $15 per musician, and even this was a stretch.

17. Caple, not Caples as has often been printed.

18. Steve Cropper recalls more than once picking up Booker from his ROTC training sessions for a recording date.

19. Wexler thinks it was Williams, while Stewart thinks that it was Reuben.

20. Estelle remembers the advance being $1,000. In retrospect, it may be hard to understand how close Stewart and Axton were to bankruptcy. According to Jim, they were having problems even paying musicians for sessions, let alone making the monthly rent. Whatever the actual dollar amount, the Atlantic money was like gold. In Estelle’s words, “That was the biggest thousand dollars I ever saw. It was like today somebody laid a million dollars in your lap. We were struggling.”

21. Although a handshake deal might seem unorthodox, according to Wexler, a precedent already existed in Atlantic’s 1955 deal with songwriters/producers Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. The Stax deal was the first complete label deal Atlantic had ever made, and was to be the precedent for later deals with Fame, Dial, Capricorn, and Alston. The Satellite (later Stax)/Atlantic distribution relationship, formalized with a written contract in 1965, remained until May 1968 when Atlantic was purchased by what became known as Warner Communications (now Time-Warner). The deal with Atlantic gave the New York company the option to distribute each Stax release, but if it felt a record did not have national potential, Atlantic could elect not to pick it up. In the first few years Atlantic declined its option on about thirty individual releases by artists such as Prince Conley, Barbara Stephens, the Canes, the Astors, the Tonettes, Deanie Parker, the Drapels, and so on. In total, though, the vast majority of Stax releases were picked up for distribution by Atlantic, although, of those, about 10 percent were initially tested in Memphis to see what sort of interest existed before it was deemed worth the investment for Atlantic to distribute the record on a national basis.

22. It was customary at the time for royalties to be paid on 90, rather than 100, percent of all records sold. This was an antiquated holdover from the days of 78s, when it was assumed that approximately 10 percent of all records shipped would break. In the late 1990s, a number of record companies still maintain this practice.