With the Chalice gospel label up and running for about a year, a greatly expanded catalogue of LP releases, and a passel of significant hit singles under his belt, Al Bell opted to further diversify the Stax operation. The November 26, 1966, issue of Billboard announced that Stax was starting a pop subsidiary named Hip. English singer Sharon Tandy (who would take Carla Thomas’s place on the majority of the Stax/Volt Europe tour shows in the spring of 1967) and Memphis group Tommy Burk and the Counts were listed as the first acts to be signed.1

Between the fall of 1966 and the split from Atlantic in May 1968, twelve records were issued on Hip; all but one were by white pop groups.2 After the split from Atlantic, twenty-two more singles were issued on Hip through late 1969. Of these, all but two—the Goodees’ “Condition Red” (Hip 8005) and Southwest F.O.B.’s “Smell of Incense” (Hip 9002)—were abject failures. The Goodees were a Memphis-based ensemble whose sound harkened back to the early 1960s girl groups such as the Angels and the Shangri-Las. Their one glimpse at the limelight peaked at number 46 on the pop charts in the early weeks of 1969. Southwest F.O.B, hailed from Dallas and featured England Dan Seals and John Ford Coley, who, under their own names, would have a number of pop hits in the late 1970s. “Smell of Incense,” their one hit at Stax, was licensed from a Texas label, GPC, and climbed to the number 56 spot on the pop charts.

Most of the pop acts signed to Hip came to the label through the auspices of Ardent Recording Studio president John Fry, entertainment lawyer Seymour Rosenberg, or Al Bell. The vast majority were not recorded at Stax. In Jim Stewart’s words: “It was rare that we got [rhythm and blues] records played on white stations, because [they were] ‘too black’ as they used to tell us, so [Hip] was a sorry effort to try and see if we could [get pop airplay with white artists].”

Rosenberg is perhaps best described as a cigar-chomping, somewhat portly musician/lawyer with a well-developed sense of humor. Many years earlier he had played trumpet with Jim Stewart as part of Sleepy Eyed John’s band at the Eagle’s Nest. A full-time lawyer, he also managed a number of musicians on the side, the most famous being Charlie Rich, whom Rosenberg represented from 1961 to 1976. For a brief while Rosenberg co-owned the American Sound Studio and Youngstown and Penthouse labels with Chips Moman. At the time Isaac Hayes recorded for Youngstown, Rosenberg also managed him. Rosenberg represented most of the disc jockeys and program directors in the Memphis area and consequently had considerable influence when it came time to get a record played. He brought Tommy Burk and the Counts, the Poor Little Rich Kids, Johnny Dark, David Hollis, and Lonnie Duval to Hip. In all cases these were finished masters that had nothing to do with the Stax studio, session musicians, or songwriters. Few of these artists were heard outside of the mid-South area.

“Stax already had a successful label,” explains Rosenberg, “and it’s an ego thing to get into the white area. Basically, I’d bring them these things I’d cut and it didn’t cost much to press up records and put them out locally. All I wanted was some exposure at the time [for the artists]. Any way you get started is a good way. As a result [of their Hip 45] the Counts went from $150 a night to $500 or $1000. … They had some sort of fame, if just local around the mid-South. Stax didn’t care much about Hip. They were doing well with R and B. It was an experimental thing. If something sold, fine, if it didn’t….” Before 1967 was over, Seymour Rosenberg became the first legal counsel Stax had ever retained.

Tellingly, neither Jim Stewart, Steve Cropper, nor John Fry remembers anyone at Stax being specifically in charge of Hip. “They just sort of had this label,” shrugs Fry, “that they would put anything on that came their way. But in terms of anybody trying to chart a course or direction from an A&R point of view, there was no function of that kind that I can remember.”

Just how far Stax was out of touch when it came to their pop efforts is best summed up by the man in charge of marketing Stax singles from 1968 to 1971, Ewell Roussell. “We were cutting the Goodees when there were groups like Led Zeppelin out there. We were trying to cut hit singles when pop music was all in albums. I just don’t think we had a caliber act.”

Although Hip was rightly put to bed before the end of 1969, Bell would make several other attempts to achieve success with pop and rock artists, mostly via the Enterprise label. All would fail abysmally both aesthetically and commercially, with the exception of Big Star’s two albums on Ardent. Even these failed to generate any sales when originally released in 1972 and 1973, but over the course of the next two decades both Radio City and Number One Record have had an inordinate influence on a host of latter-day rock bands including the Replacements and R.E.M.

Just as Stax was starting up Hip, Jerry Wexler approached Jim Stewart with an offer. Aretha Franklin had recently left Columbia Records and had signed with Atlantic. Wexler offered to lend Aretha to Stax on the same terms as he was currently lending them Sam and Dave.

“Aretha, coming from a gospel background with her equipment and ability,” related Wexler to French film director Phil Priestley, “was an ideal candidate for Stax Records’ production [team]. I could visualize her in the studio with Steve Cropper and Booker T. making incredible rhythm tracks.”3

Unfortunately, there was one proviso that had not been part of the Sam and Dave deal. Wexler wanted Stax to pay to Atlantic the $25,000 advance Atlantic had paid Franklin upon signing. By Wexler’s own admission, in 1967 $25,000 was “important money.” Stewart felt the price was more than he could afford.

“Twenty-five thousand dollars cash that was nonrecoupable to a man who was just starting to sell records and thought five thousand dollars was a lot of money” is how Stewart succinctly explained his decision in 1986. Stewart turned Gladys Knight down as well in 1967 for the same reason. He simply felt she was too expensive for his company at that particular point in time.4 Stewart’s sense of thrift in the 1960s would stand in sharp contrast to Al Bell’s management in the 1970s. You can bet that, for better or worse, Al would have signed both artists, consequences be damned.

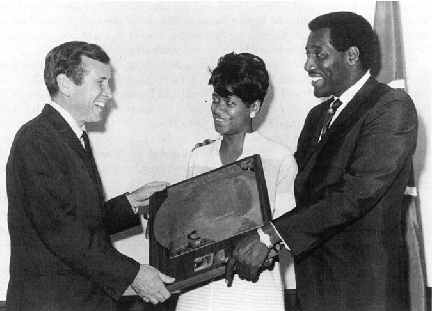

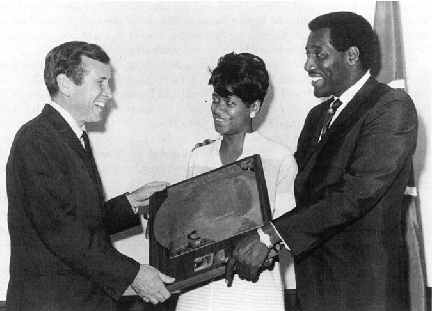

Carla Thomas and Otis Redding present a plaque to Tennessee senator Howard Baker, who wrote the linner notes for Thomas and Redding’s King and Queen album. COURTESY FANTASY, INC.

As 1966 was drawing to a close, Jim’s own Queen of Soul Music, Carla Thomas, was preparing to record an album of duets with Otis Redding. Ultimately titled King and Queen, the album would be released in March 1967. At the time album concepts were in vogue, and it was Jim Stewart’s idea to pair his leading vocalists.

“One of my contributions was to put them together,” reminisces Jim. “I had to fight to do it. They really didn’t jump overboard about the idea, but after it was done they liked it. I thought it would be helpful to both artists’ careers. Carla was always sort of special to me because she was my first artist and I felt she needed a boost. I thought the combination of his rawness and her sophistication would work.”

Carla Thomas elaborates: “There may have been a little [apprehension] because I said, ‘Well, I’m so used to singing those little sweet ballads, I don’t know how I’m going to stack up.’ So I talked with Otis and he just said, ‘Well hey you from Memphis, you from Tennessee, you can hang.’ We just ad-libbed and it came off great.”

The album was recorded in January 1967 while Carla was home for the Christmas holidays from Washington, where she was studying for her M.A. in English at Howard University. Six of the album’s ten tracks were cut with Otis and Carla in the studio at the same time. For the other four, Otis laid down his part first with Carla overdubbing hers a couple of days later, as both had concert commitments at different times during the sessions. “Tramp” was the first song cut as both singers tested the water, and each other, seeing if the combination would work. It was Otis’s idea to cover the tune, which had been a number 5 R&B hit for Lowell Fulson in 1966.

“‘Tramp’ stands out the most,” smiles Carla, “because it was the first and because of all the things I was trying to do to think up interesting lines to say to him. He said, ‘Call me whatever you want to call me.’ I said, ‘Oh, my God,’ trying to think of something to say. ‘Hey you country you this or you that.’ It helped me a lot. It brought out a lot of my hidden talents. I found out I could really talk about somebody if I wanted to. I didn’t know that until then.”

When issued as a single in April 1967, “Tramp” zoomed to number 2 R&B and number 26 pop. Two further singles were pulled from the album. Otis and Carla’s cover of Eddie Floyd’s “Knock on Wood” hit the number 8 and number 30 spots on the R&B and pop charts in September 1967, while the duo’s remake of the Clovers’ 1954 number 2 R&B hit “Lovey Dovey” was released in the winter of 1968, when it climbed to number 21 R&B and number 60 pop.

Carla asserts that there were plans to record a duet LP each subsequent Christmas. In fact, after Otis’s brief flurry of dates in early December 1967, had he lived, she said they were going into the studio to cut the followup album. Phil Walden does not remember this, but he does recall talk of Otis doing a duet LP with Aretha Franklin.

Otis had also discussed one other interesting concept for an LP with Walden. He thought of recutting a number of his former recordings rearranged back to front: ballads would be done up-tempo and vice versa. “It was an unbelievable concept he had,” marvels Walden. “His version of ‘I’ve Been Loving You (Too Long)’ was an ass kicker from front to end. A song like ‘I Can’t Turn You Loose’ was a beautiful ballad.”

Much has been made over the years about the existence of a Stax family; the magic that is so evident on the records that were recorded at 926 E. McLemore is undeniably a direct product of this family atmosphere. A number of artists would simply hang out at the studio even when they weren’t scheduled to cut. Often they would end up contributing a line or a lick to a song or singing background vocals on a session. Just as often, they would simply pass the day, shooting the shit with other artists, the MG’s, the Mar-Key horns, the Satellite Record Shop employees, or Hayes and Porter. The feeling within the company in the sixties was, in general, very close. This would change for a variety of reasons in the 1970s but, even then, it is clear that a family atmosphere prevailed, although in the later period there were two or three clearly distinct families.

In the 1960s, once the family had coalesced it tended to be quite insular and quite difficult for outsiders to penetrate. The open-door policy that had so obviously set the company in motion when Jim and Estelle had first relocated to McLemore had become a thing of the past.

Homer Banks found it particularly difficult to get in. Born the same year as David Porter, Duck Dunn, and Wayne Jackson, Banks had grown up singing gospel, at the age of sixteen forming the Soul Consolators with his lifelong friend, guitarist Raymond Jackson. The Soul Consolators sang at churches throughout the mid-South as well as at talent shows in the Memphis area, concentrating on original material that Banks and Jackson penned.

After serving the requisite military hitch between 1962 and 1964, Banks began to hang out at Stax, letting anyone who would listen know that he was a singer and a songwriter. He went so far as to cut a demo for Stax with Steve Cropper on guitar and Lewie Steinberg on bass that Jim Stewart ultimately rejected. Shortly thereafter, Banks cut a single on the short-lived Genie label written by Hayes and Porter, “Little Lady of Stone” b/w “Sweetie Pie.”5 Jim Stewart was more than a little piqued.

“When Jim Stewart found out about it,” relates Banks, “somehow or another the word got out that I was responsible [for the record]. I lured [Hayes and Porter] into doing it. That closed the door even tighter. For a long time I was barred from the studio. I wasn’t allowed to come in there.”

In a move that succinctly sums up Jim and Estelle’s relationship to each other and to those who wanted to be a part of Stax, Estelle promptly offered Homer Banks a job working in the Satellite Record Shop. “Then I really started getting serious about my writing,” says Homer. “I was up there where I could put on albums and see what was hitting, see what people were buying. I think it was a great education working in that record shop because I found the pulse of the public, what they would turn on to and turn off to.”

Homer worked at Satellite for three years. Throughout his time there, Estelle continually encouraged him, reassuring him that he had talent and urging him to keep on trying. Primarily a lyricist and melody writer, when his musical collaborator, Raymond Jackson, headed off to the armed services in 1966, Banks began writing with whoever happened to be available, including Johnny Keyes and Allen Jones.

Keyes, Banks, and Packy Axton (all of whom worked in the Satellite Record Shop) came up with a song called “Double Up” that Jim Stewart was interested in recording with Sam and Dave in the early fall of 1966. His initial discussions with the songwriters led everyone to believe that the writers and the company would split the publishing royalties down the middle. With everyone agreed, Booker T. and the MG’s worked up the song in anticipation of Sam and Dave coming to town to record the tracks for the Double Dynamite LP.

David Porter served as the go-between. According to Keyes, Porter came up to him one day and said, “‘The deal is this: we can’t give you no publishing.’ I said, ‘What?’ ‘We can’t give you no publishing but what we can give you is we’ll put it on a Sam and Dave album guaranteed. We will also pull it as a single guaranteed.’ I said, ‘What about it, Packy?’ He said, Yeah.’”

This was the sort of practice that a number of record labels had engaged in for years. Rather than splitting the publishing so that the songwriter would get both writer and publishing royalties for every sale and performance of the song, the idea was to simply keep all the publishing royalties within the company. This was standard practice at Stax but, in most cases, they would sign the writer to their publishing company, at least assuring the writer of a potential outlet for subsequent material. In this particular case, Al and/or Jim appeared to have little faith that Homer would write subsequent material of any quality and were attempting to simply keep for themselves what they thought was a creative accident on his part.

As events would have it, Keyes, Axton, and Banks eventually decided not to give up all the publishing. Keyes picks up the story: “Miss Axton came over to our apartment6 and this was the first time I had seen this body language of hers. She’s got the upper hand and she knows she’s got the upper hand. She never got excited. She got cooler, crossed her legs and lit a cigarette. She says, ‘Don’t give Jim Stewart that song. Make him split the publishing. [If you don’t] I’ll never back anything y’all do including this apartment.’ I thought, ‘Oh, oh, she’s playing her ace.’”

Before Estelle laid down the law to Packy, Keyes thought he was in line for a hit song with Sam and Dave, which he would hopefully parlay into a songwriting contract at Stax. Disappointed, he told Jim to forget it, and he and Packy headed over to Ardent, where they recorded the song with L. H. White and the Memphis Sounds.7 Shortly after, Keyes was producing journeyman soul singer Clarence Lewis, a.k.a. C. L. Blast, on Atlantic. After Atlantic let Blast go, Keyes produced “Double Up” with the singer and, ironically, Atlantic promotion man Leroy Little placed the master with Stax. Released in July 1967 on Stax and then rereleased on Hip, the song failed to sell by L. H. White or Blast.

Banks endured a similar situation in partnership with Allen Jones. In 1966, Jones had just recently been hired by Stax, auditioning tapes sent in to the company by “wanna be” artists. Working in Jones’s dingy office in the Mitchell Hotel on Beale Street,8 Jones and Banks crafted a ballad entitled “Ain’t That Loving You (For More Reasons Than One).” The aspiring songwriters played it first for Estelle and then for Al Bell. Both were impressed. Although Bell was technically still just the label’s promotion man, he was also active on an A&R level and proceeded to offer Banks and Jones a contract to buy the song outright. According to Homer, Estelle once again said, “DO NOT SELL YOUR SONG!”

Once again David Porter was the emissary Bell and Stewart dispatched, contract in hand, to Banks and Jones. “I wanted to take the contract home and show it to my wife,” recounts Banks, “and say, ‘Hey, I’m on my way!’ I was happy. But David Porter said, ‘No, I need you to sign a contract now.’ I said, ‘Well, I would like to read the contract and take it home and study over the contract.’ David Porter said, ‘If you don’t want to sign the contract, you can leave.’ He went and told Jim Stewart and Jim Stewart came back and said, ‘I want you to vacate the premises.’ Gilbert Caple said, ‘Man, I think this is ridiculous. This is a publishing company, man, and you’re gonna put a writer out just because a man wants to read a contract over? Man, this is ridiculous. This is absurd.’ Jim Stewart said, ‘Man, when David Porter tells you something, it’s like I’m telling you. If you won’t sign the contract, I want you out.’”

After Homer left feeling depressed and abused, Estelle went back into the office area and, as usual, raised hell with Jim. Eventually she got the contract in her hands, which Homer and Allen duly inspected and signed. The song sat around for a couple of months before it was finally cut by Johnnie Taylor. That’s when a real songwriting contract was at last prepared for Homer Banks. A year and a half later, Banks would cowrite the biggest-selling single Stax had to that point. In the interim, however, he was continually frustrated in his attempts to get songs approved by “the board” at the weekly Stax A&R meetings.

“I started going directly to the artist because I couldn’t get nothing in through the board,” Banks recalls, grimacing. “I said, ‘Maybe this would be a better way for me to get my songs in there.’ Otis used to come over to the record shop and listen at the gospel records. Sam and Dave [did the same thing]. I used to run to the store for these guys. I became their runner. All this was just to get some attention for my music. After a while they came and started demanding some of my stuff to cut.” Banks and Jones were able to get “What Will Later On Be Like” recorded by Jeanne and the Darlings, “Strange Things Happening in My Heart” by Johnnie Taylor, and “I’ve Seen What Loneliness Can Do” and “I Can’t Stand Up for Falling Down” cut by Sam and Dave.

“I Can’t Stand Up” was an emotion-wrought non-LP ballad that, interestingly, sounds as if it could have been written by Hayes and Porter. It is very different from what Jones and Banks wrote for other Stax artists. According to the late Allen Jones, the song was tailored to meet the Hayes-Porter formula for Sam and Dave. “They created Sam and Dave,” explained Jones. “So when [we] wrote ‘I Can’t Stand Up for Falling Down,’ it was based off of writing a song for a style that had been created by David Porter and Isaac Hayes.”

Al Bell echoes those thoughts, adding that “Hayes and Porter had the magic. In many instances Sam and Dave were merely an extension of Hayes and Porter.” In fact, Hayes and Porter often performed at local clubs doing many of the songs they had written for Sam and Dave. “We’d get out publicly”—Porter grins—“what we’d call flushing our brains, and sing in some of these clubs and people would just nut up.”

By this point the sessions for Sam and Dave had begun to take on a pattern. The duo, still living in Miami, would come into Memphis for a week at a time. Once they arrived, Hayes and Porter would spend the first few days writing and then they would teach Sam and Dave their parts around a piano. During the actual sessions, Hayes controlled the rhythm section while Porter coached the vocalists. “The structure of our sessions,” affirms Porter, “was such that I would stay [in the studio] on the other side of the mike and direct Sam and Dave on the singing of the songs. I would structure them. I would say down, up, soft, full. I directed them like you would a choir.”

Twelve days after Homer Banks celebrated the release of “Ain’t That Loving You (For More Reasons Than One),” Stax released Sam and Dave’s interpretation of Isaac Hayes and David Porter’s “When Something Is Wrong with My Baby.” One of the most sublime records in soul music’s history, the song’s lyrics were crafted by Porter while he was married to a woman whom he had impregnated when they were both still in high school.

“I was quite honestly miserable with her,” sighs Porter. “There was no love there. In the early part of my career I would fantasize about a lot of the things that I would come up with for my lyrics. I was in bed one night feeling miserable. Big house and a big car but I’m not in love and I’m not happy. I was fantasizing about what it would really be like to be in love. I got up out of bed and went downstairs and said, ‘If I was in love with somebody then the relationship should be such that if something is wrong with her, something is wrong with me.’ It was about two o’clock in the morning and I wrote the whole song.” Porter called Hayes at nine the next morning, sang it for him over the phone and said, “Man, we got a smash.”

Introduced by four ringing guitar chords followed by bass, understated snare, and piano triplets, Sam sings the first two lines in a quivering high voice full of melismas. The second half of the verse is sung by Dave, announced by swelling organ, horns, and fuller guitar and piano. The chorus drips with emotion as the two of them sing one of their odd harmony parts.

“I call them abstract harmony parts,” says Porter. “Isaac was excellent at harmonies. Isaac would come up with a note for Dave’s harmony and Dave would sing the note that he was used to singing when he and Sam had first started out in the clubs. Somehow or another it would be a distant tone from what Isaac would have given them. It often worked and we wouldn’t say anything.”

The second verse is sung entirely by Sam, culminating with the gut-wrenching “I know, I know, I got to help her solve them,” and the whole thing is brought to a close with repeated horns and drum stops, in the style of Otis’s “I’ve Been Loving You Too Long.”

Given that “When Something Is Wrong with My Baby” sailed to number 2 R&B and number 42 pop, it seems odd that Hayes and Porter did not write more ballads for Sam and Dave. David Porter agrees: “I wanted to, but when we got a niche with up-tempo things happening with Sam and Dave we just tried to ride that. [In retrospect] we should have done more ballads.”

The MG’s experienced similar success with their February 1967 release, “Hip Hug-Her.” Their first Top 10 R&B hit since “Boot-Leg” and their first Top 40 pop success since “Green Onions,” “Hip Hug-Her” eventually sold close to 400,000 copies. Booker T. credits his studies at Indiana University for some of the record’s success. “I can remember I was in college when I wrote ‘Hip Hug-Her,’” he recalls, smiling. “I remember the way I was voicing the chords. Knowing for sure what those notes were that I was playing gave me confidence I didn’t have when I recorded ‘Green Onions.’”

Cropper introduces the song with a great metallic descending guitar lick that is quickly followed by ground-shaking bass, organ, and guitar riffing. “We wrote sounds,” adds Booker. “We thought a lot about sounds.” On all of the early MG recordings Booker played a Hammond M-l or M-3 spinet model organ. This is the first MG’s single to feature the larger Hammond B-3 organ. Complete with its Leslie speaker with a spinning horn, the B-3 afforded Booker a substantially expanded palette of sounds. “Hip Hug-Her” is also unique in that it is one of the few times Duck used round-wound strings on his bass. The astute listener will notice a slightly different bass timbre.

From “Hip Hug-Her” on, the MG’s became major artists at Stax, enjoying a string of superlative releases through their demise in 1971. Booker T. Jones gives part of the credit for their ascendancy to Al Bell. “We weren’t viewed as an artist by the company before [Al Bell came]. We weren’t even listed in the meetings as artists when we talked about what artists would be cutting. Booker T. and the MG’s were not one of the viable artists at Stax. I think [Jim] was afraid of losing the house band. [Al] had the idea of, Why squash Booker T. and the MG’s as artists? Let them be an artist and bring in other people to produce and be in the studio as well.”

While “When Something Is Wrong with My Baby” and “Hip Hug-Her” worked their way up the charts, a Stax Revue to end all Stax Revues was headed to Europe. Scheduled from mid-March through April 9, 1967, the Stax/Volt tour of Europe turned out to be a watershed event for all concerned. For Booker T. and the MG’s, the Mar-Key horns, Carla Thomas, and Eddie Floyd it was their first trip overseas. For Sam and Dave, and especially for Otis Redding, it was validation of their superstar status. For the company as a whole, it was a turning point to be followed by large-scale expansion, as the “little label that could” began to move beyond its regional roots and family-based approach. At one and the same time, the tour was a culminating point beyond most people’s wildest dreams and the beginning of the end of the label’s Memphis-centered classic period.

For everyone involved in the tour the reception in Europe was simply overwhelming. “I was aghast,” recalls a still stunned Steve Cropper. “They treated us like we were the Beatles or something. It pretty much overwhelmed everybody in the band. The only one that knew for a fact what it was gonna be like was Ahmet Ertegun. He was totally aware of the situation. We had no idea. It was absolutely amazing.”

“I was shocked when we went to Europe,” adds Booker T. “Why would they want us to come over there? I couldn’t believe it. People knew my songs in Scotland and France. It was really a surprise.”

Cropper told Peter Guralnick, “It was totally a mind-blower. Hell, we were just in Memphis cutting records; we didn’t know. Then we got over there, there were hordes of people waiting at the airport, autograph hounds and all that sort of stuff. … That was something that happened to Elvis or Ricky Nelson, but it didn’t happen to the Stax-Volt band.” Mar-Key trumpeter Wayne Jackson put it to me more succinctly: “Europe opened our eyes.”

Affectionately dubbed “Hit the Road Stax,” the tour was a brainstorm initially hatched by Redding’s manager, Phil Walden. Upon returning to the United States after Otis’s first trip to England and France in the fall of 1966, he immediately pitched the idea of the tour to Jim Stewart and Al Bell. “The Stax/Volt tour was all mine,” asserts Walden. “I financed the tour. If I had been a little more sophisticated in those days, those records would have been my records.”

The timing was perfect, as in October Atlantic had announced that Stax was to get its own label identity in Europe in 1967. The first European Stax-labeled releases distributed through Polygram—Eddie Floyd’s “Raise Your Hand,” Sam and Dave’s “Soothe Me,” and Otis Redding’s cover of the Beatles’ “Day Tripper”—came out just as the tour got under way.

The posters for the tour read “Arthur Howes in association with Phil Walden and Stax Records present….” Howes was a British concert promoter at the time. Walden’s integral involvement explains why Redding’s protégé and non-Stax artist Arthur Conley was on the bill and why in some early ads the tour was touted as “The Otis Redding Show.” It might also explain why Otis, for the first time, was plainly treated differently from the rest of the artists and musicians, staying separately from everyone else in his own suite in a better hotel. Needless to say, this caused a bit of head shaking and resentment among those who had known him back in the days when he was just starting out. Howes and Walden would go on to partner other European soul tours, including a fall 1967 venture headlined by Arthur Conley, Sam and Dave, and Percy Sledge.

Back in Memphis there were some bitter feelings about who was chosen to go on the European tour. Rufus Thomas, for one, felt that he deserved the opportunity. Carla Thomas appeared on only a handful of dates because she had to fly back to the States to appear at a civil rights benefit in Chicago, a booking that was made for her by Al Bell for his own or the label’s benefit and/or to pay back a favor to the benefit’s organizers. Carla lost valuable exposure because of this obligation. In her opinion, what would have been good for her career was sacrificed in favor of what was good for someone else. Twenty years after the fact it still rankled.9

The artists who were involved were informed about the tour just a couple of weeks in advance. The four members of Booker T. and the MG’s and the Mar-Key horns were immediately sent to Lansky Brothers on Beale Street to buy two sets of Continental suits, one in green, one in blue. To be able to make the tour, saxophonist Andrew Love talked Floyd Newman into subbing for him in Bowlegs Miller’s band. Duck Dunn, Wayne Jackson, and Joe Arnold weren’t so lucky. To their dismay, they were forced to quit their regular six-night-a-week gig at Hernando’s Hideaway to go on the trip. Dunn, along with the other three MG’s, had been put on salary a little before the European venture.10 For Jackson and Arnold, though, this was a serious economic decision.

“Charlie Foran [the owner of Hernando’s] told me, ‘Don’t come back if you leave me for a month,’” recalls Wayne Jackson, “’cause we had the place packed out there. I thought I was gonna go to Europe, make my little two thousand dollars, which was a lot of money at the time. My house note was sixty-eight dollars, so two thousand was a lot of money. I thought that would probably be the end of it. The big Stax thing went to Europe and toured and came home and, poof, it was over!”

For the most part, the musicians did not get to rehearse until they got to London. Wayne Jackson laughs: “Everybody assumed that Booker T. and the MG’s had played on the records, the Mar-Keys had played on the records, and we knew the stuff—wrong! You use slate memory when you’re doing records. You remember something for three minutes over and over and when you start the next song, you erase that. We didn’t play those numbers all the time. We had to try to learn a bunch of them, we had to hustle real hard. We had to rehearse the day we got there with no sleep and hung over, of course. It was like a ship constantly on the verge of going out of control.”

Jackson’s compatriots in the Mar-Key horns at the time were tenor saxophonists Andrew Love and Joe Arnold. Arnold recalls the horn players rehearsing stage steps in Memphis prior to the tour, partially inspired by the visually dynamic stage show of label mates the Bar-Kays. Andrew Love concurs: “The Bar-Kays were good at that. They did a lot of stepping and swinging horns and all of that kind of stuff, more so than we did. So we decided we needed to have a little movement up there, add a little excitement to it. We got together in Studio B and practiced, you know, step to the left on beat one [and so on], like we used to do in high school bands.” Both Arnold and Love thought that the idea of working on steps came from either Isaac Hayes or Al Jackson.11

Although there had been a few one-shot gigs over the years—such as the 5/4 Ballroom shows in 1965, the Apollo gig in 1966, and the odd show in Memphis—this was the first time a Stax Revue had actually gone on the road, playing a series of shows in a variety of cities. The excitement that the tour engendered is permanently etched in everyone’s memories. When asked if he was excited, Wayne Jackson responded, “Are you kidding me? I came from West Memphis, Arkansas. I never figured I’d get across the river. I had a camera on both hands—a movie camera and a still camera! We thought this was just one chance in a lifetime. I thought this was just a gift from God. He said, ‘Okay, guy, you get a trip.’

“We were exhausted. We couldn’t sleep because we knew we were going to miss something. [We thought] this was our only shot at it. I couldn’t believe I was in Norway riding down the road passing Viking ships and museums.”

Andrew Love echoes Jackson’s sentiments. “It was a BIG deal! We tried to do everything and see everything we could, because maybe we’d never get the chance to come back again. We took so many pictures. Man, I was taking pictures of clouds. I wasted so much money. You get those pictures back and all you see are clouds and the propeller of a plane.”

Carla Thomas has similar memories of the trek: “That was happy. I mean I was never in my hotel room—ever! Everything you want to see in Paris, I saw it. England too. I was just a real live tourist!” To everyone’s chagrin, outside of Paris and London, there was not that much time to sightsee. Wayne Jackson described a typical day’s itinerary as getting up at seven o’clock, traveling to the next city by bus or train, arriving mid-afternoon, eating, showering, “running down the street and looking at something,” and then playing one or two gigs.

Most of the entourage arrived in London on Monday morning, March 13.12 The Beatles sent their limos to pick up the band which, in Andrew Love’s words, “WAS REALLY A BIG DEAL!” After two days of rehearsal, Carla Thomas played a warmup gig with Booker T. and the MG’s at a private London club with restricted admittance called the Bag O’Nails. With a capacity of about three hundred people, this club was a hangout for various stars; Thomas’s strongest memory of the evening is meeting Paul McCartney. She and her sister Vaneese had gone to see the Beatles in Memphis the previous August and, of course, she was performing McCartney’s “Yesterday” on the Stax/Volt tour.

“We talked with him a minute between sets,” Carla fondly recalls, “and then I had to go back. When we finished, he got up to go. I said to Booker, ‘Let’s follow him.’ We leapt up out of the club behind him. I said, I’m going to talk some more to him. I’m just not through with this situation.’ It wasn’t anything much. We were just kind of walking with him. I told him, Thanks so much for coming. I’m so honored.’”

The tour officially opened on Friday night, March 17, when the Revue played two gigs at the Finsbury Park Astoria. As with most venues for the tour, the Astoria held between two and three thousand people. Atlantic engineering ace Tom Dowd had flown over for the first few shows, and Frank Fenter, A&R for Polygram (which was distributing both Atlantic and Stax in Europe), suggested that Dowd record the Finsbury Park shows. Scrambling as quickly as he could, the best equipment Dowd could find for portable recording in London were two three-track machines. He used both machines in tandem with a five-minute delay between them so that he didn’t miss any of the show when he had to change reels. With only three tracks to work from, all mixing was done on the fly. Dowd recorded both shows at Finsbury Park as well as two shows at the Paris Olympia on the following Tuesday, the twenty-first. In Paris, Dowd was able to locate two four-track recorders.

The touring group then proceeded to play a series of one-nighters in England before heading to the continent for shows in Oslo, Stockholm, Copenhagen, and the Hague before returning to London for a final performance on April 9.

The Finsbury Park and Olympia tapes were made into four albums released that July: The Stax/Volt Revue Volume One: Live in London; The Stax/Volt Revue Volume Two: Live in Paris; Otis Redding Live in Europe; and The Mar-Keys and Booker T. and the MG’s: Back to Back. In addition, two-and-a-half weeks after the tour ended, Volt issued a live version by Otis Redding of Sam Cooke’s “Shake” on 45, followed a month later on Stax by a live version of Sam and Dave’s cover of the Sims Twins’ “Soothe Me.” Both live 45s reached number 16 on the R&B charts while stalling in the middle of the pop Hot 100.

It might seem odd to record a tour at the outset, rather than documenting the final climactic shows when any flaws would have been worked out and the band would be operating at red-hot intensity. However, Carla Thomas could only stay in Europe for a week due to her prior commitment to play the Chicago civil rights benefit, so the decision may have been made to record the early shows in order to include her on the records. Joe Arnold, for one, claims that the later shows were much better.

Phil Walden as well felt that the shows kept getting better and better. By his own admission, his days of being a fan were long over; he now attended gigs more out of duty. Europe was an exception. “Every night was more exciting than the previous one. There was never a climax. The thing just kept getting better. You would never know how it could be better than it already was.”

That said, what was recorded at those first few shows has an intensity matched by very few live recordings. Booker T. and the MG’s and the Mar-Key horns had been a unit in one guise or another for just over five years, backing Carla Thomas, Sam and Dave, Eddie Floyd, and Otis Redding on virtually every recording they had ever made. The empathy and sense of second sight exemplified by all seven musicians is still a revelation some thirty years after the fact.

The first half of the show featured, in order, Booker T. and the MG’s, the Mar-Keys, Arthur Conley, and Carla Thomas, while the second half commenced again with the MG’s, followed by Eddie Floyd, Sam and Dave, and Otis Redding. The MG’s started the evening off in high spirits, ripping through what had been a B-side when it was originally released in late 1965, “Red Beans and Rice.” Next up was another B-side, which charted in the summer of 1966, “Booker-loo.” The MG’s finished their first mini-set with the song that had started everything for them, 1962’s “Green Onions.” The taut, always-on-the-edge tension of the group was one of the riches of popular music in the twentieth century.

Booker T. and the MGs live in Europe: (left to right) Booker T. Jones, Duck Dunn, Al Jackson, and Steve Cropper, COURTESY FANTASY, INC.

The Mar-Key horns were up next, performing their two biggest charted records, “Last Night” and “Philly Dog.” Both songs featured heated tenor sax solos, on the former courtesy of Andrew Love, on the latter by Joe Arnold. Both based their solos on the originals recorded by Gilbert Caple and Gene Parker, respectively.

Many commentators have noted an element of freneticism in the European performances captured on the live-in-Europe records. In his excellent Sweet Soul Music, Peter Guralnick wrote, “There is a frenetic note that is at odds with the spare classicism of the Stax sound.” Empirically it is a fact that the tempos were greatly increased, attacks were sharper and there was, in general, less room for the music to breathe. The question becomes then, was this better or worse than the actual recordings made in the studio in Memphis?

Jim Stewart, for one, felt that it was worse. Phil Walden recalls an enraged Stewart bursting into Otis’s dressing room after the first show in Paris. “He stormed into the dressing room: ‘Otis, you got to drop those tempos and drop them right now. We’re taping this and trying to make a record.’ Otis said, I’m over here playing a fucking date. I make records in Memphis, Tennessee. Don’t tell me about my tempos. I’m out here entertaining these people. They don’t know shit about this record we’re making and the tempos are gonna stay that way if we’re gonna make it ’cause I’m over here playing a date. That’s my career out there.’ Jim [responded], ‘You’re a fucking star!’”

In my estimation, the Stax/Volt Revue live had an intensity altogether different from that found on the records. As good as the Stax/Volt artists were on their own, on the very few occasions when they were backed by the MG’s and the Mar-Key horns they rose to exceptional heights. Carla Thomas’s performances of the at-the-time recently released Isaac Hayes-David Porter composition “Something Good (Is Going to Happen to You)” is a case in point. Collectively the band inspires Thomas to deliver a performance that is hard-hitting in a way that is totally unlike anything else she has ever released.

Also unique in Carla’s canon was her cover of the Beatles’ “Yesterday.” At the Paris shows the song was partially sung in French. It was Thomas’s idea to attempt it, learning the first and part of the fourth verse phonetically the day before the show. She finished her mini-set and the first half of the show with the two hit singles that Hayes and Porter had penned for her the previous year, “Let Me Be Good to You” and “B-A-B-Y.”

Eddie Floyd’s set varied each night. On every show, he would sing three or four songs out of a total of seven or eight that he had rehearsed. “Raise Your Hand” and “Knock on Wood,” of course, were always performed. The rest of his set consisted of one or two covers including J. J. Jackson’s “But It’s Alright,” Chris Kenner’s “Something You Got,” Chuck Jackson’s “I Don’t Wanna Cry,” and the folk group the Weavers’ “If I Had a Hammer.”

Sam and Dave came on next, generally performing six songs, their five chart hits—“You Don’t Know Like I Know,” “Hold On! I’m Comin’,” “Said I Wasn’t Gonna Tell Nobody,” “You Got Me Hummin’,” and “When Something Is Wrong with My Baby”—plus a cover of the Sims Twins’ “Soothe Me.” Walden found them intoxicating. “I think Sam and Dave probably will stand the test of time as being the best live act that there ever was. Those guys were absolutely unbelievable. Every night they were awesome.”

“Every night you would feel sorry for Otis,” adds Wayne Jackson. “Sam and Dave had taken this audience to heaven and back. They’d have to carry them off. They would jump out in the audience and just go crazy like they were having a fit and then jump back onstage and faint. They would have to carry Dave off like he was dead and then they would carry him back on like he was resurrected. By the time that was over with, all the wax on the floor was gone, burnt up. Otis would be standing there in the corner praying.”

Eddie Floyd remembers the European audiences as being comparable in their frenzied response to those of the Apollo Theatre. For Wayne Jackson they went beyond that. “Sam and Dave left that stage smoking, and when Otis would come on he had to be up. He had to be at his finest. [The audience] was just frothing at the mouth when [Sam and Dave] left, and then when Otis got through with them it was just total chaos. People were weeping, gnashing their teeth, screaming and jumping up and down.

“They rushed the stage like Elvis. We had guards along the stage on that particular tour who actually had to keep people off the stage. I mean drag crying women away, [people] tearing their clothes. First time I had seen that in person. [It was] scary. They were crazed, their eyes were glassed over, and they were wanting to be involved with [Otis] so bad. They would have run right over me.

“Otis was amazed by it. He loved it. Of course, he egged them on, holding his hand out. He was a master showman.”

In Scotland, Redding was actually dragged into the audience, and the cops and security guards had to go out after him and pull him back onstage. Every night he turned in an incendiary set. This was a “new” Otis, demonstrating a level of confidence and bravura a notch above earlier outings. The records bear evidence that he obviously loved the English audience, speaking tongue-in-cheek in London of how “it’s good to be back home,” referring to London as “the greatest city in the whole world,” and dedicating “My Girl” (a UK-only hit from his Otis Blue set) to the Astoria audience.

All six songs in Redding’s nightly set were stellar, but “Day Tripper,” “Fa-Fa-Fa-Fa-Fa (Sad Song),” and “Try a Little Tenderness” stood out.13 As was his wont, Otis completely redefined the Beatles tune, while “Sad Song” was usually turned into an audience sing-along with the MG’s, Mar-Keys, Redding, and the audience alchemically melding into one.

“Try a Little Tenderness” was the finale of his set and the whole Stax/Volt Revue. Phil Walden recalls that it had been suggested that Redding close with the New Vaudeville Band’s “Winchester Cathedral.” “They actually worked on it,” says Walden, shaking his head. “It was fucking awful. Otis kept singing ‘Westchester Cathedral.’ I think that’s the most unsoulful song. … Finally, good judgment prevailed and it was not used.”

The studio version of “Try a Little Tenderness” increased the tension as the song progressed via accentuated tempo, increased density, additional volume, and Redding’s near-inhuman vocal machinations. Live, all those elements were stepped up to the nth degree as over seven minutes each night the song would alchemize into a white-hot rage with Redding leaving the stage and coming back three times, each time raising the temperature, while testing the pumping capacity of everyone’s hearts, band and audience alike. Otis would eventually be joined onstage by Sam and Dave, Eddie Floyd, Arthur Conley, and Carla Thomas for the final, climactic, neuron-stopping volley.

As exciting as the shows were, Europe itself was a bit of a culture shock. “Basically,” recounts Walden, “I think they felt like they were a group of blacks held captive. They all hated the food. They were all about to basically starve to death.”

Tom Dowd recalls having Sunday dinner at a prestigious hotel in London with Jim Stewart, Steve Cropper, Duck Dunn, and Sam and Dave. The waiter, as Dowd describes him, was wearing white cotton socks with buckles on his shoes and a puff by the ear, looking like nothing so much as a character out of a Charles Dickens novel. As the waiter was explaining the specials of the day in his best upper-crust accent, Dowd gets an elbow in his side with one of the party exclaiming, “Say, what language is he talking.” Duck Dunn, who was seated right across from Dowd, rolled his eyes at the waiter and said, “Ask him if he’s got any fatback cacciatore.”

“This man is looking at us as if we’re crazy,” guffaws Dowd. “I’m thinking I must be three shades of purple. The dialogue was just precious.”

The Stax/Volt tour of Europe wasn’t all great music and fun and games. At one point a meeting was held with everyone crowded into Al Bell’s room, during which, according to Joe Arnold, Bell threatened to leave Stax if certain changes did not occur. Arnold says that the gist of the whole affair was that Bell thought that Steve Cropper had a big head. When all was said and done, Arnold describes Steve as looking like a whipped dog.

Arnold found the whole incident unsettling. He was also a little piqued over the fact that, with Wayne Jackson doing all the interviews for the horns, press coverage of the tour tended to focus on Jackson to the exclusion of Love and Arnold. Additionally, while the rhythm section had been put on salary at Stax, the horn players were still working for session fees. Shortly after landing back in Memphis, Arnold handed in his resignation.

Arnold’s departure appears to have been a wake-up call for Jim Stewart and Al Bell; Wayne Jackson and Andrew Love were immediately put on salary, making $250 a week each plus whatever they picked up working sessions at Muscle Shoals and Hi. Who would have ever guessed that life could be this good? “God damn!” exclaims Wayne. “We started [with the extra sessions at the other studios] to make four hundred dollars a week. Andrew and I had a house and a new car and the kids were in school and doing good, which is more than we had ever expected out of the deal. It was really for me sort of a fluke!”

Sessions continued apace at Stax and the money was good, but somehow the feeling was slightly different. “When we got back home,” recounts Jackson, “we went back to work but it was never the same again. When we saw the audience reaction to us it was unbelievable. [Up to then] we didn’t know we were stars. We thought we were kids working at the club to make enough money to pay the rent and making records just getting by. We found out there was a big world out there and that we were a big part of that world. We weren’t just playing horns in a nightclub and putting horn parts on other people’s records for a fee. We had had an impact. I think we felt that [playing theaters] was what we’d rather do than play at Hernando’s [Hideaway in Memphis]. After [Europe] my mentality changed. I knew that I didn’t have to play six nights a week and kill myself. At that point we were getting old enough to where it made a difference. You can’t take speed all your life every day. We [had been] doing a lot of that to stay up.”

For several years, both Jackson and Love had endured quite a grind, playing at the clubs every night into the wee hours in the morning, and then arriving at Stax at 11 A.M., ready to record. Sessions often continued until 8:00 at night, when they’d hurriedly pack up and head for that evening’s gig.

“It would be eight or eight-thirty,” said Wayne, speaking with London disc jockey Stuart Colman in 1986, “and Duck and I’d still be in blue jeans. At that time you had to put on a suit to go play rhythm and blues in a nightclub. I’d be driving and Duck would be in the backseat changing clothes. Then we’d stop at a red light and switch. We’d walk in the club at one minute to nine P.M.”

With the security of a steady income, Jackson and Love decided to play gigs on the weekends only, resurrecting the Mar-Keys’ name for these performances. After they quit Stax in late 1969, they would change their name to the Memphis Horns.

The success of the Stax/Volt tour catapulted Otis Redding into a superstar in Europe. At the end of that year, he was named the number 1 male vocalist in Melody Maker’s annual readers poll, dethroning Elvis, who had dominated that category for years. It also paved the way for Otis’s appearance at the Monterey Pop Festival in June. Monterey was to be the first important rock festival. Held over three days, it boasted an astonishing lineup of established rock artists, including Simon and Garfunkel, the Byrds, the Who, Eric Burdon and the Animals, and Jefferson Airplane, and provided the launching pad for Jimi Hendrix and Big Brother and the Holding Company featuring Janis Joplin—as well as Redding.

The three major black artists approached to play the festival were Hugh Masekala, Lou Rawls, and Otis Redding. When Lou Adler first approached Walden to ask if Redding would be interested in playing the date, he explained that, as was the case with all the artists playing the festival, there would be no fee involved but that the exposure alone would make it worthwhile. After consulting with Jerry Wexler, Walden concluded that Monterey was going to be an important event and a possible stepping-stone for Otis to the emerging rock and roll audience.

However, there was a bit of a problem because Otis was planning to take time off to have some polyps removed from his throat and had consequently broken down his band. The logical alternative would be to get Booker T. and the MG’s and the Mar-Key horns to back Redding up. By this point Walden’s relationship with Jim Stewart was so bad that he asked Jerry Wexler to call Jim to ask if the Stax house band could take time off from the studio to fly to California to back Otis on the date.

Monterey was a shock for everyone. “It was space travel,” exclaims Walden. “This was right when the hippie shit was really just starting to happen. It was all peace, love, and water beds. It was a cultural shock. I had seen a little bit of everything but I had not seen people openly smoking dope and taking acid. I don’t think too many people in the world have ever been totally free that way. It was like a spaceship had landed for a few days.”

“There were the hippies smoking pot right in public,” affirms Wayne Jackson. “It was another planet for us. At that time I thought if you got a marijuana cigarette, the next day you’d be on heroin and then jail was two days later with the FBI. I really did. That’s what we were taught when we were kids. I was that naive about it.”

“Monterey was a wake-up call,” says Booker, “because we’d just come back from Europe and we had acceptance there. We had never had acceptance from [a white] audience in the United States. It was like Monterey should have been in Germany or maybe Holland, but it was California. It was our first announcement that something new was happening culturally and musically in the United States. There was a new feeling. The policemen were gone. We were led into the concert by Hell’s Angels. They were protecting us! You could walk into a restaurant in Monterey and get a free sandwich. Hotels were opened up to people. It was a completely different feeling. History was changing at that moment and we knew it. I think it affected the way we played that night.”

At 55,000 strong, Monterey was the largest audience Otis, as well as the MG’s and the Mar-Key horns,14 had ever faced. The MG’s hadn’t played with Otis since the European tour some two months previously and had only about an hour and a half to rehearse in a hotel room acoustically without a keyboard. Encountering the counterculture for the first time, everyone was a little nervous as to how they might go over. “Us in our mohair green suits,” laughs Duck Dunn. “Everybody else in their flower power!” “Some of them [were] really cool,” adds Wayne Jackson. “Here come us, we’re energetic and doing organized steps. We thought maybe we’re gonna bomb because we were so very different from the rest of these people. The fact is we took it away from everybody else.”

Otis was slated to close Saturday night, coming onstage right after the Jefferson Airplane. Wayne Jackson emphatically recalls: “When Otis came on it was over. Over. End of story for everyone who had played up to that point. The crowd went absolutely bananas. Andrew and I were just shaking. They were mobbing the stage just wanting to touch Otis. When we got through with them, they were insane.”

“The feeling there was really unbelievable,” Steve Cropper continues. “It was unmistakably different from any other concert we’d ever done. There was something in the air other than smoke.” “The audience was on our side,” adds Booker. “It wasn’t like they were looking at us to see what we had to play. They were saying, ‘We’re part of you.’”

Otis referred to the audience from the stage as “the Love Crowd,” and love him they did. Phil Walden made the right move. With one masterful performance, white America began to awake to the power and majesty of Otis Redding and the Stax house band. Monterey was the most cataclysmic event in an incredible year for Otis. The festival also helped Booker T. and the MG’s. After their triumphant performance there, they were regularly booked on the rock festival circuit15 and in the psychedelic ballrooms that were beginning to spring up throughout urban North America.

A couple of months earlier, a few days after the conclusion of the Stax/Volt tour of Europe, Stax released the debut single by what was being groomed as their second set of studio musicians. The Bar-Kays had been playing around Memphis for a while at this point, having evolved out of a group known as the Imperials. The new name was inspired by a Bacardi Rum billboard at the intersection of Crump and Georgia in Memphis. Trumpeter Ben Cauley recalls that the “Kays” were the first “stepping” band in Memphis. Getting into Stax had not been easy.

“We had auditioned for Stax several times,” recounts bassist and bandleader James Alexander. “Each time we auditioned, Steve [Cropper] would turn us down. In his opinion, we didn’t have what it took to be a recording artist. Jim [Stewart] had heard about the group and he told us we should come down one day when Steve was not there.”

The Bar-Kays did as Jim suggested on March 13, 1967, and ended up cutting a hit record that same afternoon, a stomping instrumental dubbed “Soul Finger.”16 The rhythmic idea for the song occurred to the band while they were onstage backing future Soul Children member Norman West performing J. J. Jackson’s October 1966 hit “But It’s Alright.” “At the end of the song we started jamming a little riff,” explains Cauley, “extending the song, ad-libbing and stuff, and we came up with the [‘Soul Finger’] rhythm to settle it down.”

In the studio the band was working on a version of Phil Upchurch’s “You Can’t Sit Down,” which Jim Stewart felt would be a good first single. At one point during the session he went out to get a Coke. When he came back into the studio, the Bar-Kays were jamming on “Soul Finger.”

“Jim walked back in,” laughs Cauley. ‘“What’s that y’all are doing?’ ‘Oh, it’s just something we all made up.’ ‘Do it again, do it again.’ So we did it again man, and he just about flipped. ‘That’s a hit. let’s cut it.’ So we cut that version, and we said, ‘Now there’s still something missing here.’ We got to thinking and I always would do little comical things on trumpet, so I did ‘Mary’s Little Lamb’ and they said, ‘Why don’t you put that on the front of it, man.’ It started happening from that point on. We cut it in about fifteen minutes.”

The title was provided by Hayes and Porter. As well, Porter came up with the idea of bringing in a bunch of local children who were hanging around outside the studio to shout the song’s title and to carry on as if there was a party ensuing while the record was being made. “I bought them all Coca-Colas,” recalls Porter, “and I said, ‘Every time I do this, you all say “Soul Finger.’” Then I instructed [Bar-Kays bassist] James Alexander what he should say into the microphone.”

“Soul Finger” clocked in at the number 3 rhythm and blues and number 17 pop positions. The B-side, “Knucklehead,” written by Steve Cropper and Booker T. Jones, also charted, reaching number 28 R&B and number 76 pop, with the multitalented Booker T. Jones playing the harmonica part.

A few days after “Soul Finger” was released, Billboard announced that Stax was issuing a special promo-only LP entitled Stay in School (Stax A-l 1). U.S. Secretary of Labor Willard Wirtz had approached the label to “carry the message of the 1967 ‘Stay in School’ campaign to the nation.” Four thousand copies of the album were pressed, which were then distributed by the Department of Labor in August as a public service to disc jockeys and radio stations across the country. Deanie Parker coordinated putting the album together. Most major Stax artists including Carla Thomas, Eddie Floyd, William Bell, Sam and Dave, and the Mar-Keys contributed brief speaking cameos encouraging children to continue their education. In addition, a number of recently released LP tracks by the various artists were included alongside two new tracks, Sam and Dave’s “Reason for Living” and Otis Redding’s “Stay in School” song. The latter was improvised on the spot with Otis accompanying himself on acoustic guitar; the Mar-Key horns were overdubbed later on.

Early Bar-Kays promotional shot: (front row) Phalon Jones, James Alexander, (back row) Jimmie King, Carl Cunningham, Ronnie Caldwell, Ben Cauley. COURTESY API PHOTOGRAPHERS INC.

MG drummer Al Jackson and blues guitarist extraordinaire Albert King. COURTESY DEANIE PARKER

Billboard also mentioned that Stax/Volt artists were participating in a U.S. Domestic Peace Corps recruitment campaign, recording a message asking youngsters to enlist in the Corps. The messages were to be coupled with the various artists’ current releases, with the government shipping copies of each record to radio stations in the spring to serve as spot announcements for the Corps. It is uncertain if this project ever came to fruition, because no copies of these recordings are known to exist.

Altruistic gestures like the Stay in School album garnered a certain amount of free publicity for the label and its artists. Deanie Parker confirmed that Stax was well aware of this potential: “Wherever and whenever we could, we did take advantage of it from the standpoint of artists expounding on their participation in it, and we tried to make certain that the country was aware of the fact that we were participating in a project to keep children in school.” For a brief period, the message on the marquee outside of the company’s studio was changed from “Soulsville U.S.A.” to “Don’t Be a Dropout.” When neighborhood children greeted the new message with a barrage of rocks one evening, it was quickly changed back.

In May 1967, Stax released Albert King’s “Born Under a Bad Sign.” Soon thereafter covered by the rock group Cream, over the years the song has taken on classic status. Surprisingly, it only reached number 49 on the rhythm-and-blues charts when originally issued.

Booker T. Jones and William Bell wrote the song. “We needed a blues song for Albert King,” recalls Bell. “I had this idea in the back of my mind that I was gonna do myself. Astrology and all that stuff was pretty big then. I said, ‘Hey, we’ve never had a blues tune done about astrology. I got this idea that might work.’” In addition to the lyrics, Bell had also come up with the song’s signature riff while fooling around on guitar. The Albert King recording of “Born Under a Bad Sign,” with Booker T. and the MG’s providing the accompaniment, remains one of the most smokingly intense blues recordings of the modern era.

Born Under a Bad Sign was also the title of Albert King’s first LP. Containing the singles “Laundromat Blues,” “Oh, Pretty Woman,” “Crosscut Saw,”17 and the title track, the LP surprisingly failed to chart pop or R&B. One has to keep in mind that the rhythm-and-blues market remained almost totally a 45 market until the early 1970s. Stax, in fact, via Isaac Hayes, would be the first R&B label to sell substantial numbers of albums. In 1967, though, neither Atlantic nor Stax could generate much retail action for their LPs. Compounding this was the fact that a blues artist such as King would invariably sell fewer records than a more mainstream soul singer such as Otis Redding.

“Born Under a Bad Sign” was one of the last Stax singles whose label read “Produced by Staff.” Ten days later, Stax 221, “Sophisticated Sissy” by Rufus Thomas, was released with the bold declaration “Produced by David Porter and Isaac Hayes.” From this point on, any newly recorded product was released with individual production credits.18 This small change was the first outward manifestation that some of the company’s community spirit had begun to erode. Europe had been an eye-opener. Anyone who had made the trip concluded that Stax was much bigger than they had ever realized. Those who remained in Memphis heard enough about the reaction to the tour to take on the same attitude. Individual production credits were just one manifestation of this trend.

“There was a shared kind of responsibility for a long, long time,” recounts Deanie Parker, “until people began to appreciate the value of developing a reputation as a producer. The first person to lead out with that kind of attitude, and it created a little bit of friction, was Steve Cropper. Steve is very aggressive and did not, in my opinion, necessarily support that cooperative idea for as long as maybe the others would have in a passive way.”

Despite the changes clearly in process at Stax, the label continued to issue records of astonishing power throughout the rest of the year. With a typical Memphis summer beginning to heat up, Hayes and Porter went into the studio to cut “Soul Man” with Sam and Dave. As was their by-now standard procedure, before the session began they took time out to shoot craps. “The artists would be all on their knees,” howls William Brown, who was still working in the record shop. “ ‘Lord have mercy, I done lost my paycheck.’ [David Porter would reply] ‘That’s all right man, we’ll cut a hit record. We’re gonna have lots of money’ ‘Still you ain’t gave me my paycheck back!’” Whenever William would play he’d find himself running errands for everyone just to make a little change back.19

“Soul Man” turned out to be the most successful Stax single to date, topping the R&B charts and hitting number 2 on the pop listings. Sam and Dave would win a Grammy for the single in the second-ever year of the category “Best Rhythm and Blues Group Performance” during the March 1968 National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences ceremonies. They had been nominated the previous year for their recording of “Hold On! I’m Comin’,” but on that occasion they failed to take the gold home.

“Soul Man”’s title continued where “Soul Finger” left off, in the process helping to provide a handle for a whole genre of music. “That was during the days of civil rights struggles,” recounts Isaac Hayes. “We had a lot of riots. I remember in Detroit, I saw the news flash where they were burning [the neighborhoods]. Where the buildings weren’t burnt, people would write ‘soul’ on the buildings. The big thing was ‘soul brother.’ So I said, ‘Why not do something called “Soul Man” and kind of tell a story about one’s struggle to rise above his present conditions’ It’s almost a tune [where it’s] kind of like boasting I’m a soul man—a pride thing. ‘Soul Man’ came out of that whole black identification. We got funkier.”

“Soul Man” was an important record, keying in to the then-newly emergent black consciousness that was perhaps best summed up by the phrase “Black is beautiful.” In 1967 it became an anthem for black America.

Opening with Steve Cropper’s chiming guitar juxtaposed with Isaac’s low-register piano and Al Jackson’s atmospheric riding on the bell portion of his cymbal, the song is infused with syncopation. Duck Dunn claims that Isaac Hayes was responsible for a lot of the funk rhythms on these records. “All those counterpoint things, those pieces that fit together, that was Isaac. You listen to that record ‘Soul Man.’ The guitar part and the bass part are basically ‘Bo Diddley’ He’s got everything moving around. It works. It just knocked me out. When he did it that day, I said, ‘Isaac, son of a bitch, he knows what he’s doing.’”

One of the most memorable portions of the recording occurs in the chorus, when Sam and Dave exclaim “I’m a soul man” four times in a row. Following the second declamation Steve Cropper plays a slide guitar part that has burned deep into the consciousness of anyone who has ever heard the record. The guitar line was Isaac Hayes’s idea. Hayes said, “Give me some Elmore James, man,” referring to the great blues slide guitarist. Cropper, not having a proper slide with him, used a cigarette lighter to get the sliding effect. Sam Moore was so knocked out when he heard it that he spontaneously injected “Play it Steve” into the mix. The excitement was so palpable that it was all left in.

“Soul Man” epitomizes the Stax sound as much as any record. The key aesthetic was one of “less is more,” applied to all players and across all parameters. Drummer Al Jackson’s trademark cannonlike backbeat on the snare is juxtaposed for most of the performance with an eighth-note ride pattern on a closed hi-hat cymbal. Jackson typically opted for the closed hi-hat, as opposed to using suspended crash or ride cymbals, which fill up a much larger portion of the pitch spectrum and continue to ring for some time after they are initially struck, creating a much wider and longer sound. The closed hi-hat reinforced the aesthetic of “less is more.” To compliment this aesthetic even further, on many recordings the hi-hat is played so quietly that its presence is nearly subliminal.

“We used to basically try to keep cymbals out of most of the songs,” explains Steve Cropper. “We thought cymbals were offensive. Demographically we were told that research [showed] that girls bought probably seventy to eighty percent of the records and, if a guy bought one, it was usually because he was buying it for his girlfriend. We thought that women’s ears were a little more sensitive and they didn’t like cymbals so much, so we tried to keep them way down in the mix almost all the time.”

Jackson used a wooden shell snare drum and, by tuning its top head loosely, achieved very little of the taut, metallic properties that many drummers seek. Instead, he produced a deadened sound using very tight snares to dampen the bottom head of the drum. To deaden the sound even further, Jackson would put his billfold on the top head of his snare drum.20 At the same time that he was altering the snare’s basic timbre, he played very hard, hitting the rim and the skin of the snare at exactly the same moment with the heavy, thicker end of the stick. The net result was a readily identifiable sound that truly packed a wallop.

On records Jackson was a simple drummer, generally avoiding embellishments of all kinds, including drum fills typically found at the ends of sections in much popular music. When he did play fills, they would often occur as part of an interlocked pattern worked out with bass, guitar, and keyboards. The exception to this was on Booker T. and the MG’s recordings, where Jackson generally played much more complex and flashy parts, often utilizing added timbres such as a cowbell.

A key ingredient in the conception of the Stax groove was that Jackson had an absolute metronomic sense of time. “He was the best timekeeper I’ve ever played with,” Cropper told writer Bruce Wittet in 1987. “If we made forty takes of a song—if we cut it all day long—you could edit the intro of the first take with the fade-out of the last take, and the tempo would be identical.”

Jackson was pretty well in control of setting the tempo for most Stax recordings, often setting them a little slower than some might have preferred. Duck Dunn recalled in conversation with Wittet, “Ninety percent of the time Al was right. I’d get a little irritated sometimes, but I would keep it to myself. His tendency would be to take the tempos slower than I could feel them.” Dunn told me basically the same thing but added, “Either you played with Al or you didn’t cut it. Either you played Al’s feel or there was no feel at all. He communicated to the whole band that way—with his playing and with his eyes.”

Stax recordings are groove-oriented, and although Jackson could be absolutely metronomic, he was much more than a glorified human click track, often allowing a performance to “breathe” by changing the groove either without changing the tempo or by deliberate subtle tempo adjustments as the piece moves from one section to another.

Timbre was a crucial component of the Stax aesthetic. Overall, the sound was bass-heavy with Duck Dunn playing a Fender Precision bass through an Ampeg B-15 amplifier. Dunn was a stickler for using flat wound strings. “As the flat wound strings got older,” explains Dunn, “they get more of a thud. They match the kick drum with more of a thud than a tone.”

Cropper was just as particular about the sound of his guitar. He would always leave his Fender Telecaster wide open, using his amplifier to set the levels. He steadfastly refused ever to use the bass pickup on his guitar, instead opting for the middle position with both pickups on or just the rear treble pickup activated. This partially accounts for the trebly sound he so obviously preferred. The Fender Telecaster that he used for most of his years at Stax had a rosewood neck, which he felt helped to give him a “real nice, biting sound.”

Cropper preferred big, heavy-gauge Gibson Sonomatic strings, generally using ten and eleven or two eleven-gauge strings on the top two strings of his instrument rather than the more typical spread of nine- and twelve-gauge strings used by most of his contemporaries. This was important for the two-note sliding figures he commonly played on his highest strings.

“It sounds better when they’re closer matched,” Steve explains. “I hate new strings on a guitar. There are guys I love and respect that change strings after every solo. Mine, I change them when they break. I even put Chapstick (lip balm) on my strings when I put them on. I just rub it into the strings. It sort of gives you the effect of two or three days of playing them where you get the grease in there and the dirt.”

This grease helped give Cropper his characteristic clipped rhythm sound. “A lot of the clipped sound just comes from my style of playing. I play right over the bridge. A lot of the muting things, a lot of the guys, the only way they can get it is to play it backwards, which is an up stroke. I play it with a down stroke. The mute comes within the fingers ’cause all of a sudden my hand isn’t on the bridge anymore. I hit the strings with a pick and the finger at the same time. The mute is coming out of the finger. [With the left hand] I finger the chord but I don’t press it down all the way so it rings. I let up just enough where they all have the same amount of deadness.

“When I’m playing ‘chinks’ like that, I don’t play dead in the middle of the fret. I play closer to the fret so it’s this bright [sound]. I can almost play a wrong chord and nobody would know the difference. That’s how unmelodic it is. It’s more percussive.”

Much of Cropper’s playing is performed on the top four stings of the instrument. In doing so, he achieved a high degree of congruence between his sound and that of the horn section. This level of timbrai integration was another key component of the Stax sound.

Floyd Newman tells an interesting story in which Jim Stewart stopped a take because he heard a wrong note. Stewart began to chastise the horns until Newman pointed out that the horns were not even playing, because they had yet to work out their part. Cropper was the guilty party, but as Stewart heard it, it was the horns. In Newman’s words, “For some strange reason [Cropper] would blend right on to the horns.” The idea of congruence was not lost on Booker T. Jones either. There are a number of examples where the piano blends into, gets lost inside of, or simply seems to become “one” with the guitar. When Jones played organ, he was equally adept at blending with the horns. He generally preferred piano when accompanying a vocalist, while the organ was his instrument of choice on most of Booker T. and the MG’s instrumental recordings.

The horn players at Stax were interested in a simple but fat sound. To achieve this goal they often played unison lines such as in the introduction, verses, and refrain of “Soul Man.” “If we didn’t feel [the sound] was coming out as fat as it should be,” explains Joe Arnold, “we would just drop one harmony part and have one tenor and trumpet double [playing the same note] and the other tenor play harmony.”

Arnold tells an interesting story that indicates just how sound-conscious the Stax house band was. He had been with the label a few months when Wayne Jackson called him and said that Steve Cropper wanted to talk to the horns at the studio.

“I hadn’t been there very long,” relates Arnold, “and at that time I was playing with a metal mouthpiece. Gene [Parker], Andrew [Love], and Floyd [Newman] all used a hard rubber mouthpiece. Steve called us into the control room and he played some tapes back of some of the stuff that had been recorded before I was there and some of the stuff that had been recorded after. Some of it didn’t sound as full.

“He was trying, in a nice way, to get around to a point. He said, ‘It just don’t seem like it’s as fat as it should be.’ I thought I was fixing to lose my job. Wayne said, ‘No man, ain’t no way, don’t worry about that.’

“See, a metal mouthpiece pinpoints the sound. That’s the reason people use the metal mouthpiece to get a sharp edge, whereas a hard rubber mouthpiece rounds it out. I said, ‘Well, I’ll get a hard rubber mouthpiece and we’ll start from there.’ From then on, no problem. I never heard any more about it.”

Booker T. claims that while the Stax house band was sound-conscious in general, they were not particularly conscious of constructing a Stax sound: “No idea, no idea at all. It came from outside. I heard about the Memphis sound. I heard we were creating the Memphis sound. We didn’t consciously generate that. That sound had been created [by the time we] realized we were creating a sound.” Conscious or not, the sound the four members of Booker T. and the MG’s, Isaac Hayes, and the Mar-Key horns created was original, distinctive, and filled with magic. The house of Stax would have been very different with a different set of players.

It also would have been very different without Al Bell. While “Soul Man” was storming up the charts, Stax announced that Al Bell was being promoted from national promotion director to the newly created position of executive vice president. Bell continued to supervise all aspects of national promotion and publicity, but now he was additionally officially recognized as a consultant to the production department.

Within a month of his promotion, Bell announced a distribution deal with Lenny Ceour’s Milwaukee-based Magic Touch label. This would be the first of several such distribution deals Bell would make in which Stax would distribute smaller R&B independents. The new arrangement produced immediate dividends when Harvey Scales and the Seven Sounds released “Get Down” (Magic Touch 2007) in October, reaching the number 32 and number 79 positions on the rhythm and blues and pop charts respectively.

In late November and early December, Otis entered the Stax studios for one monumental three-week bash. Otis was always prolific, but the wealth of material cut in this period was simply phenomenal. It turned out to be enough to fill four posthumous LPs plus both sides of a Christmas single. Steve Cropper explains this unprecedented burst of energy: “There was only one reason and that was because he had his throat operated on. He was singing better than he ever had in his life, it was just obvious. So we went back and listened to the things that had been cut on four-track. Things that he didn’t sound all that good on, we recut them; things that probably would never have come out. Some of them were over a year old.”