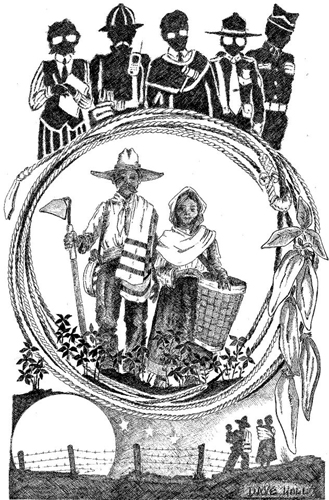

Being raised in Las Cruces, New Mexico, and presently living forty miles from the frontera in Arizona, I am steeped in the Mexican culture. Furthermore, making my living in agriculture, I can appreciate the immigrants’ enormous contribution to the “cheap food” policy closely guarded and maintained by the U.S. Congress. These workers are responsible for more than just the jalapeños in our cornucopia.

HISPANIC AGRICULTURE

“I’m concerned that more Hispanics aren’t going into agriculture as a profession.” So spoke my old friend Buddy, who is Hispanic himself. He was president of the state Ag Chemical Association. He has three grown children, none of whom show any interest in their dad’s or granddad’s agricultural livelihoods.

I have given this phenomenon much thought since our discussion, and I keep coming back to the same reason for it: Maybe most Hispanics associate agriculture with hoes. They want to be as far from the reminders that their parents, grand-parents, or great-greats came across the border and spent their lives in toil.

In a recent survey of the one hundred most influential Hispanics in American business, 77 percent of which were descended from Mexico and Cuba, not a single one had an agricultural affiliation. Over 50 percent were included in government; the majority of the rest were evenly divided between corporate business or were entrepreneurs. These findings certainly confirm Buddy’s assertions.

I grew up in the Southwest. My home county is 65 percent Spanish-speaking. I have a great respect for Mexican immigrants, legal or illegal. They have traits I admire: ambition, bravery, self-control, stamina, and a desire to improve their condition. I like to think if I was trapped in hopeless class prejudice and economic oppression, I’d climb a wall or swim a river, too.

Mexican labor has been the backbone of southwestern agriculture for centuries. As it has been for every other race of immigrant people, it is the first generation in a family that bears most of the burden and suffers the perils, the drudgery, the fear, and prejudice.

Even today, Mexican immigrants are mostly poor rural people. The skills they possess include a feel for land and stock, dirt, water, and produce. It is natural for them to seek work they are accustomed to.

A regular or even seasonal paycheck at minimum wage here in the land of plenty can make them rich men back in their hometowns in Mexico. Should they choose to stay and raise their families here, they can earn a decent living. But they hope for a better life for their children. They send them to school and insist they speak English.

Yet, as Buddy says, rarely do these descendants pursue an occupation in the business where their ancestors have had such a great impact.

America today is becoming a service-oriented society. It does not place much value on farming, mining, or timber occupations. Matter of fact, it looks down on any job that involves manual labor.

But any farmer or cowboy can tell you it is honorable work that requires skill and gets hands dirty. What is more manual than scooping a bunk, shoeing a horse, building a fence, blocking beets, or picking oranges?

Maybe with many Mexican Americans, the memory of pickin’ cotton is too fresh. But like Buddy, I agree that American agriculture could benefit from the now bilingual, educated, assimilated descendants of Señores Juan, Tomas, José, and Maria, who gave them a start.

Agriculture for them offers more than just blisters and sore backs. Abuelito already paid that price.