Ireland’s Public Debt – Tell Me a Story We Have Not Heard Yet …

Seamus is a lecturer in the School of Economics in University College Cork.

There has been an ongoing, and at times confusing, debate about what Ireland’s public debt will be in 2015. This chapter aims to look at some of the different elements of Irish public debt and the factors that can pull us away from the precipice of a sovereign default. This would be relatively straightforward if there was a universally accepted definition of public debt; there is not.

Economists are at heart storytellers. As storytellers, economists decide what matters for their purposes; they are, in a word, selective. By appreciating economists as storytellers, the general public can perhaps appreciate better why economists disagree. The spectre of default in Ireland is an exemplar of storytelling and how appreciating the choices the economist as storyteller makes is crucial in enabling the reader of such stories entering into that economist’s imaginative world. So, let me tell you a story of default.

As a starting point we will use the general government debt (GGD) measure as defined in the Maastricht Treaty of 1992. This is the measure used by Eurostat when compiling EU data and is also commonly used by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Organisation of Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). The GGD is the consolidated gross total of all liabilities of general government.

In the GGD no allowance is made for any assets that may offset some of these liabilities. The GGD is simply the total of all general government liabilities. The Maastricht Treaty laid out the rules for entry and participation in the single currency. One of these was that the GGD could not exceed 60 per cent of a country’s nominal gross domestic product (GDP). At the end of 2011 only four Eurozone countries satisfied this limit: Finland, Luxembourg, Slovakia and Slovenia. All other countries were in excess of the 60 per cent limit.

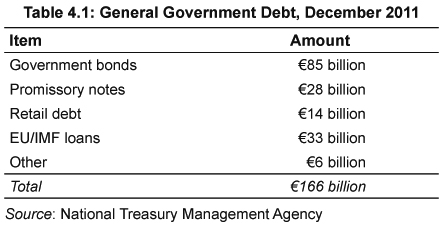

At the end of 2011, Ireland’s GGD was €166 billion. The composition of this debt is shown in Table 4.1. Although we are still awaiting the final figure it is likely that 2011 nominal GDP will be around €155 billion. This means our debt to GDP ratio is probably 107 per cent.

It is also important to note that there was €13 billion of cash in the Exchequer Account at the end of 2011 which is not offset when determining the GGD.

Just as there is no single definition of public debt, there is no universally accepted threshold of where this debt becomes unsustainable with a default viewed as inevitable. The 60 per cent threshold was chosen for the Maastricht Treaty simply because this was viewed as a ‘safe’ level of public debt. At the time of the introduction of the Euro in 1999, original members of the Eurozone such as Belgium and Italy already had debt that was above 100 per cent of GDP.

Recent studies have shown that a public debt in excess of 80 per cent of GDP has a negative effect on economic growth, but this is not the same as saying the debt is unsustainable. In a European context it is likely that a debt ratio in excess of 120 per cent puts a country in grave danger of seeing its debt spiral out of control.

At the end of 2011 the Greek debt ratio was well in excess of this level at 160 per cent, with Italy right on threshold at 120 per cent. In 2011, Ireland, with a debt of 107 per cent of GDP, was below this threshold and while there are some (including me) who envisage the debt ratio stabilising and subsequently falling away from these levels, there are many who see the debt ratio breaking through this threshold and continuing to rise. In one view default can be avoided; in the other it is inevitable.

To see why the choice of these thresholds is not universal we simply have to look at the example of Japan. At the end of 2011, the Japanese GGD was 230 per cent of GDP. This is more than twice the Irish ratio but there is no one writing books stating that Japan is on the verge of default. At the end of 2011 the yield on ten-year Japanese government bonds was less than 1 per cent. Investors in Japanese bonds do not think they will default either.

There are a myriad of reasons as to why Japanese debt is sustainable at 230 per cent of GDP while default is the only outcome for Greece with a debt of 160 per cent of GDP. The key one is that the Japanese government controls the Bank of Japan, which can simply print more yen to repay their debts. Greece cannot avail of anything like this facility with the European Central Bank (ECB).

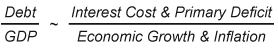

The debt ratio is a straightforward calculation that puts the total debt in the numerator and the level of GDP in the denominator. Changes in either will bring about changes in the ratio.

In order for the debt to be sustainable it is necessary that the average interest rate on the debt is less than the sum of the growth and inflation rates unless the government runs a sufficiently large primary surplus. The primary balance is the budget balance excluding interest payments. If a country is running a primary deficit and the interest rate is greater than the nominal growth rate the debt ratio will rise unsustainably.

At the time of the Budget in December 2011 the Department of Finance estimated that nominal growth in 2012 would be 2.3 per cent and that there would be a primary deficit in 2012 of 4.1 per cent of GDP. In both cases we miss the debt sustainability criteria. The interest rate on our debt is more than double the growth rate and there is no primary surplus to offset this interest cost. In 2012 the GGD is forecast to rise from 107 per cent to 114 per cent of GDP.

Over the coming years the nominal growth rate is forecast to rise to around 4 per cent a year, though changes to real growth or inflation will affect this. This will still be below the average interest rate on our debt, which is forecast to be 5.2 per cent in 2015, so in the absence of a sufficiently large primary surplus the debt ratio will continue to rise.

The primary balance is forecast to move from a deficit of 4 per cent of GDP in 2012 to a surplus of 3 per cent in 2015. It is this improvement in the public finances that will stabilise the debt ratio. If these conditions are satisfied in 2015 the debt will fall from 117 per cent to 114 per cent of GDP over the year.

This dynamic was improved considerably by the EU decision in July 2011 to reduce the interest rate on loans provided as part of the EU/IMF programme. This decision reduced the average interest rate on Irish debt by about 1 per cent and substantially increased the impact of a primary surplus on the debt ratio. If these interest rate reductions were not granted it is unlikely that the debt ratio would have been contained.

To see why this debt sustainability story is plausible we are going to do two things. First, we will explore how the GGD got to €166 billion by 2011; and second, what it will rise to by 2015.

At the end of 2007, Ireland’s GGD was €47 billion. This is the debt level we brought into the crisis, which was largely a result of the previous crisis in the public finances in the 1980s. In general governments do not repay debt, rolling it over instead by borrowing anew. From 2007, the debt then increased by €119 billion in just four years.

From 2007 to 2009, the cash balances in the Exchequer and other accounts increased from just under €4 billion to almost €17 billion. During 2008 and 2009 the National Treasury Management Agency had the foresight to borrow funds on international markets to build up these cash balances before Ireland was shut out of the bond markets in late 2010. This increase in our cash buffer accounts for about €13 billion of the rise in the government debt.

Financing the services provided by government in these four years required €59 billion of borrowing. This was necessary to fill the gap that emerged between government revenue and government expenditure and to ensure that the government could meet its pay, pensions, social welfare and interest outgoings. Interest expenditure over the four years was €13 billion.

Separately, there is the money that has been used for the bailout of our delinquent banking system. By the end of 2010, the Exchequer had contributed around €9 billion directly to the banks. This was evenly split between borrowed money paid into the National Pension Reserve Fund since 2007 that was subsequently used as part of the initial recapitalisations of AIB and Bank of Ireland, and direct contributions from the Exchequer to Anglo, Irish National Building Society (INBS) and EBS.

There was also the creation of €31 billion of promissory notes given to Anglo, INBS and EBS in 2010. These are a promise by the state to pay this money to the banks, but the payment will be spread out over an extended period. The first instalment of €3.1 billion was made in March 2011 and these will continue well into the next decade until the full amount, plus accrued interest, is paid to these zombie institutions. The final cost of repaying the promissory notes has been estimated at €48 billion and if these repayments continue to be made with borrowed money the total cost of the promissory notes will exceed €80 billion by 2030.

We will look at Anglo and INBS in more detail in a later section but it is important to remember that the cost of the promissory notes and the cost of the recapitalisation are not the same thing. The repayments on the promissory notes include €17 billion of interest. This is being paid to Anglo Irish Bank and INBS, which are state owned. They in turn are using the promissory notes to avail of emergency liquidity from the Central Bank of Ireland. They are paying interest to the Central Bank for this facility. The Central Bank will make a profit on this and will return the interest to the Exchequer as part of its annual surplus. The interest on the promissory notes is not a cost to the state as much of it will be returned.

In 2011 there was a further stress test and subsequent recapitalisation of the other four covered banks: AIB, Bank of Ireland, EBS and Permanent TSB. The Central Bank estimated that the four banks would need to be recapitalised by €24 billion in order to be in a position to absorb the losses projected over the next three years by the consulting firm BlackRock.

Significant haircuts undertaken with subordinated bondholders in the banks provided about €5 billion of this amount. Some asset disposals by the banks and private sector investment in Bank of Ireland reduced the amount to be covered by the state to just under €17 billion. Of this, €10 billion came from the further liquidation of the assets built up in the National Pension Reserve Fund so the additional debt from the bank recapitalisation was around €7 billion.

The €119 billion increase in the GGD from 2007 to 2011 can be broken down as follows:

- €13 billion to build up cash balances

- €59 billion to fund government services

- €47 billion for the bank bailout

Although it attracts the most attention, the banking disaster has contributed just 40 per cent of the increase in the GGD over the past four years. The next issue is where the debt level is going to go over the next four years.

At this stage the only thing certain to increase the debt over the next four years are the annual deficits. Some steps have been taken to try to control the deficit but it remains at very high levels. Between 2012 and 2015 it is estimated that a further €40 billion will be required to finance the annual deficits across all areas of government. The deficits for the four years are forecast to be €13.6 billion, €12.4 billion, €8.6 billion and €5.1 billion. This will put the debt at €206 billion in 2015.

This is substantially lower than some earlier estimates of our 2015 debt. For example, in early 2011 the IMF were forecasting that the 2015 debt would be €225 billion and debt sustainability was only possible if some very optimistic growth projections were used. However, since then there have been some positive developments for Ireland’s debt dynamics.

The original EU/IMF programme set aside a €35 billion ‘worst case scenario’ contingency fund for the recapitalisation of the banks, of which €17.5 billion was going to be borrowed. As we now know the 2011 recapitalisation required less than €7 billion of additional borrowing. The reduction in the EU interest rates will reduce the forecast by around €3 billion while there was a €4 billion reduction in the starting point because of a ‘double counting error’ in the Department of Finance revealed in November 2011.

The IMF also used 2014 as an endpoint for the programme meaning their 2015 deficit is on a no policy change basis. This put their original 2015 deficit forecast about €3 billion higher than will be the case as the budgetary adjustment programme is now extended in 2015.

In total, these developments over the past year mean that the IMF’s forecast of Ireland’s 2015 GGD can be reduced by more than €20 billion. After four years of almost unrelenting bad news and deteriorating projections it is encouraging to see that some forecasts are finally beginning to improve.

Of course, all these deficits, plus the rollover of existing debt will require substantial amounts of funding. Could it be the case that we will default because we will run out of money?

The current EU/IMF programme is designed to run until the end of 2013. Ireland needs €46 billion in 2012 and 2013 to fund the annual deficits, meet the payments on the promissory notes and repay the maturing of existing debt. We still have to draw down around €34 billion of loans as part of the EU/IMF programme. The remaining €12 billion is expected to come from state savings schemes, our existing resources and some market funding.

Ireland had €13 billion of cash in the Exchequer account at the end of 2011. Without additional funding the state can meet all its obligations through to the end of 2013. It is also forecast that €1.5 billion a year can be raised through the state savings schemes such as savings bonds, prize bonds and the national solidarity bond. In 2011 these raised €1.36 billion. If the €1.5 billion was achieved we would have around €4 billion left in the Exchequer account at the end of 2013. Without market funding this would be a very weak position to be in as there is a €12 billion bond maturing on 15 January 2014 and we will need €10 billion to fund the Exchequer deficit that year.

We could run out of money in January 2014 but that will not happen. The National Treasury Management Agency has already carried a bond swap that has pushed the maturity of about one-third of the January 2014 bond out to February 2015. This reduced the amount of funding we will need in 2014. It is hoped that the state will ‘dip its toe’ back into the bond market in late 2012/early 2013 to try to raise some new market funding. At this remove it appears unlikely that this will be able to raise the necessary amounts.

However, at the EU summit on 21 July 2011 it was agreed that programme countries would continue to be funded after the terms of the original agreements have ended. At the time, Michael Noonan said, ‘there’s a commitment that if countries continue to fulfil the conditions of their programme, the European authorities will continue to supply them with money, even when the programme concludes’ and also ‘if we’re not back in the markets, the European authorities will give us money until we’re back in the markets.’ Ireland will not run out of money that will force it into a default.

There are other issues related to the banking collapse that are not included in the GGD. These are, the final outcome of the NAMA process, whether the shutdown of Anglo and INBS will require further injections of capital and how to unwind the €110 billion of liquidity the banks have taken from the European and Irish Central Banks. There is also the long-term hope that we will be able to sell off our stakes in the two ‘pillar’ banks to recoup some of the money swallowed by the bailout. There is a great deal of uncertainty about all these.

The NAMA process has seen the creation of €31 billion of bonds used to buy over €72 billion of developer loans from the banks with an average discount of 58 per cent. These bonds are a liability of the state but following a ruling of Eurostat they are not included in the GGD. It is impossible to know what the final outcome of the NAMA process will be. NAMA did create €31 billion of bonds to buy the developer debt, but it bought assets which also had a notional value of €31 billion as valued in November 2009. If these levels were to be maintained beyond the November 2009 valuation date, NAMA would have no effect on our net debt position. Of course, property prices have not been unchanged since November 2009 and in fact have tumbled ever downward. There are some estimates that the value of property backing the loans has fallen by a further €5 billion since the NAMA valuation date.

It is impossible to use this as a projection of possible NAMA losses. In most cases NAMA has control over the loans and not the assets. NAMA has been making substantial disposals for the past year but we are not told if the agency is making a loss or even possibly a profit on these transactions. These sales have allowed NAMA to begin repaying the bonds issued when the agency was formed. NAMA has the potential to make a call on the state’s resources to cover a shortfall in its operations. Of the €31 billion of bonds created, €1.5 billion are subordinated bonds which will not be repaid if the agency generates a loss. Unless there is an almost complete collapse in asset values it is hard to see how this shortfall could be more than €5 billion, and it is likely to be substantially less than that.

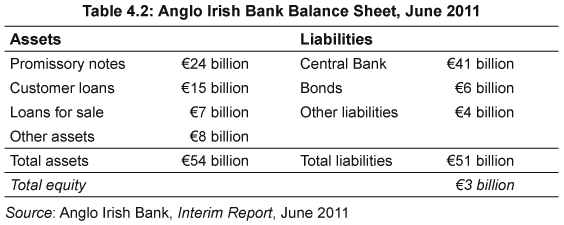

The Irish Bank Resolution Corporation (IBRC) was formed with the merger of Anglo Irish Bank and the Irish Nationwide Building Society in September 2011. The IBRC is a wholly state-owned bank and its liabilities are equivalent to sovereign liabilities. In its last set of accounts, produced for the first six months of 2011 Anglo revealed it has outstanding liabilities of €51 billion, of which €41 billion was owed to the Central Bank of Ireland. There was around €6 billion of bonds and €4 billion of other liabilities. A summary of Anglo’s last balance sheet is provided in Table 4.2. These liabilities could be included in the GGD and it is possible that a change to reflect this will be introduced.

On the asset side we can see that half of these liabilities are already covered by promissory notes issued by the state and that there is €3 billion of equity in the bank. Consolidating the accounts would mean that about €20 billion of Anglo liabilities would be added to the GGD. The figure for the INBS part of the IBRC will be less than a quarter of this.

This change would increase the debt ratio by 15 per cent of GDP and push the debt ratio above 130 per cent of GDP. It is important to realise that this change would not put any additional cost on the Exchequer but would merely allow the GGD to better reflect the gross liabilities of the state.

There will only be an additional cost to the state if the assets on the balance sheet are not able to meet the liabilities to be paid (of which 80 per cent is owed to the Central Bank of Ireland). The IBRC has already disposed of some of these. The loans for sale category includes a €6 billion US loan book which was sold for around €5 billion in October 2011. This loss was provided for in the above accounts. This €5 billion was used to repay some of the emergency liquidity assistance the bank is availing of from the Central Bank of Ireland.

Customer loans amount to €24 billion, with €15 billion in Ireland and €9 billion in the UK. All US loans were classed as loans for sale. A loss provision of €9 billion on customer loans gives rise to the €15 billion figure used in the balance sheet. This is a write-down of around 40 per cent.

Figures on the loan book performance show that only 45 per cent of the loans are non-impaired. It is difficult to forecast what the recovery rate on non-performing loans will be but achieving 60 per cent of the nominal value of the loans seems probable. The bank does have around €3 billion of equity (which was provided by the state of course) but this means that a loan loss rate of greater than 50 per cent would be required before any additional state resources would be required.

The inclusion of the IBRC would increase the GGD but would not mean that additional state support for the bank is necessarily required. If no additional support to the bank is required the inclusion of the IBRC in the GGD cannot make debt sustainability any less likely. Only losses on the bank’s customer loans above 40 per cent or on its other assets can cause that.

The €110 billion of Central Bank liquidity the banks have obtained is also backed by assets that have a nominal value well in excess of €110 billion. Outside of the IBRC, these are largely the customer loans the banks have issued. Between the NAMA process and the recent stress tests, €85 billion of loan losses have been accounted for in the covered banks. Other losses provided for in the banks’ annual accounts (such as the €9 billion discussed in the Anglo accounts above) and covered by the former equity they held would bring this even higher. It is likely that well over €100 billion of loan losses in the covered banks have already been accounted for and there are no credible estimates that they will be higher.

The banks have substantial liabilities to central banks, bondholders and depositors. Without state assistance they would not be able to meet these liabilities. The state has provided €63 billion to the banks to cover this shortfall. If the banks are not to meet their liabilities it would require losses above those already accounted for to materialise. There is little to suggest that this is the case. In time the covered banks can unwind their reliance on Central Bank funding. This will be achieved as loans are repaid or sold and by acquiring deposits, particular inter-bank deposits, as confidence in the Irish banking system is slowly restored.

What all the above shows is why there is such confusion about Ireland’s public debt and why there is no hard rule on what constitutes an unsustainable level of debt. Ireland’s public debt is massive and is set to grow over the next few years. However, it is very probable that the debt ratio can be controlled and, in time, will fall away from the extreme levels it is currently exhibiting.

Using the current definition, Ireland’s GGD was €166 billion at the end of 2011. With nominal GDP of around €155 billion the debt was equivalent to 107 per cent of GDP. It is possible to get a number that is much larger than this.

If NAMA’s €30 billion of liabilities are included the debt would be 124 per cent of GDP. If the consolidated liabilities of the IBRC are added the debt would be around 140 per cent of GDP. If we are just picking numbers out of the air we could add another 10 per cent of GDP for no good reason other than the banks have huge levels of Central Bank liquidity drawn down. As we’re at it we could add in over €100 billion of unfunded pension liabilities that the state will face over the coming decades. In the space of a single paragraph we have gone from a high but manageable debt of 107 per cent of GDP to a huge and unsustainable debt of 220 per cent of GDP.

In fact, neither figure proves that the debt is manageable or unsustainable. What truly decides whether a debt mountain is sustainable or not is the interest burden it puts on the public finances. Japan can carry a debt of 220 per cent of GDP because it can borrow at less than 1 per cent interest over ten years. This keeps Japan’s interest expenditure at manageable levels. As countries rarely repay public debt the decisive issue is not the size of the debt but the amount of government revenue that goes to pay the interest on the debt.

State bodies such as NAMA and the IBRC, and even semi-states like the Dublin Airport Authority and the ESB, have huge debt levels. However, because they have their own assets, the interest payments they make do not come out of general government revenue. In fact, most of these bodies have sufficient assets to allow them to not pay the interest but also to fully repay the debts they have accumulated.

These debts could appear on the government’s balance sheet and give the impression that the state is going to be utterly overwhelmed by debt. However, it is not the liabilities of these bodies that have to be covered by the state but the losses. And even then it is the interest burden that covering these losses would generate rather than the size of the losses that matters. If NAMA and the IBRC have €20 billion of losses to be covered by the state, then borrowing at 5 per cent would put an interest burden of €1 billion on the state. This is a huge sum of money but is not one that will result in national bankruptcy. There is no suggestion that these bodies will generate additional losses of more than a small fraction of this amount.

While there is uncertainty about these losses, there is no uncertainty about the ongoing need to fund the annual budget deficit. Taking the end-2011 debt of €166 billion, and adding the €40 billion needed for the deficits, means that by the end of 2015 the GGD will be in the region of €206 billion. This is the Department of Finance’s forecast, the European Commission’s forecast, will be the IMF’s forecast, and, for what it is worth, it is my forecast.

Servicing the €206 billion debt mountain we have created will cost about €8 billion a year in cash interest payments. This is the total amount of cash interest the state will have to pay on its debt. Different aggregate debt levels can be obtained whether one includes or excludes a whole range of items. The cash interest to be paid is not open to such interpretation. There are huge government debts in NAMA, the IBRC and other bodies but because they have their own resources the interest on these debts will not be a drain on the government’s resources.

A cash interest bill of €8 billion is a huge burden to carry. It will be about 4.5 per cent of GDP and most of this will be paid to external creditors. By 2015 general government revenue is forecast to be around €62 billion with tax revenue of €43 billion. This cash interest will consume close to one-eighth of total government revenue (or one-fifth of tax revenue). The actual servicing cost will depend on the average interest rate, which is estimated to be 5.2 per cent.

Of course if the 5.2 per cent was applied to the €206 billion debt then it suggests that the interest payments should be over €10 billion. The €206 billion will include about €20 billion of promissory notes and there will be nearly €2 billion of interest added to them in 2015. This interest is paid to the state-owned IBRC which in turn will be paying interest to the Central Bank of Ireland for emergency liquidity. The interest due on the promissory notes is not paid to the IBRC but is rolled up into the capital amount. The IBRC will receive a fixed payment of €3.1 billion per year from the Exchequer until the promissory notes plus interest have been paid off. The presence of the promissory notes increases the government debt but does not affect the cash interest payments to be made.

An €8 billion annual interest payment is a huge burden for the country. However, at this stage, default remains an option to be considered rather than an inevitability to be endured.

We will also have substantial assets that would allow us to reduce the debt. In the above analysis we will also still have €13 billion of cash reserves intact. If we exhaust our cash reserves the debt would be €193 billion, but such an action would not be prudent. Although much of the National Pension Reserve Fund has been liquidated to recapitalise the banks there is still around €5 billion remaining in the fund. The banks have also been provided with €3 billion of ‘contingent capital’ which is due to be returned to the Exchequer in 2014.

The debt will also be lower once, hopefully, a sale for the banks can be undertaken. We have complete ownership of AIB and Permanent TSB and a 15 per cent stake in Bank of Ireland. Although it seems unlikely at present there may yet come a time where we will be able to offload the banks and use the money generated to repay the debt. The amount raised will be nowhere near the €63 billion we have poured into the banks but it will usefully reduce the debt.

It is hard to put a value on the banks but it will be some non-trivial sum. It is easy to suggest that the cash reserves, National Pension Reserve Fund and contingent capital would reduce Ireland’s net debt to GDP ratio to around 100 per cent. If 10 per cent of GDP could be obtained for the banks the net debt position would be 90 per cent of GDP. If you prefer GNP as the appropriate measure of the Irish economy we are probably looking at a net debt in 2015 that will be around 115 per cent of GNP: large but by no means terminal.

Table 4.1 shows the breakdown of Ireland’s €166 billion GGD at the end of December 2011. In November 2011 a Greek ‘default’ of 50 per cent on sovereign bonds held by private investors was agreed with the EU. There were many calls that Ireland should seek a similar write-down on its debt. As the table shows, Ireland has €85 billion of outstanding sovereign bonds with another €5 billion to be repaid in March 2012.

The covered banks have around €12 billion of Irish government bonds on their balance sheet. Any write-downs here will have to be made good by capital injections from the state so the net benefit of a default on these bonds would be reduced by the money we would have to put into the banks. The ECB holds an estimated €22 billion of Irish government bonds as a result of the bond buying programme that it has been undertaking since the middle of 2011. The ECB has declared itself not to be a private creditor. This means the 50 per cent write-down would apply to about €50 billion of government bonds which would generate a total debt reduction of around €25 billion. If the Greek ‘default’ was applied to Irish debt it would reduce the debt total by 15 per cent and bring it down to 90 per cent of GDP. The ongoing deficit and the likely increased interest cost of the remaining debt would quickly see it rise back above 100 per cent of GDP.

As was pointed out above it is not necessarily the size of the debt that matters but the interest burden it places on the government. If a 50 per cent haircut was applied to privately held Irish government bonds it would reduce our interest bill by €1.25 billion per annum, assuming that the average rate on the debt written off was 5 per cent. It is forecast that the general government deficit for 2012 will be €13.6 billion. It would still be above €12 billion if the 50 per cent debt write-down was applied. Even an 80 per cent write-down would only knock €2 billion off the annual interest bill.

It should also be noted that this is only on the assumption that the interest rate on our remaining debt remains unchanged. It would take an increase of only 1 percentage point on the remaining €124 billion of debt to fully offset the interest savings from the initial write-down. It is highly probable that such a rise would occur.

Any Irish default would have to focus on sovereign bonds but these are not held in sufficient quantity by private investors to generate sufficient benefits to offset the undoubted costs that would follow such an action. A default worthy of the name would require losses to be forced on official creditors. Much as it might seem desirable or attractive, it is not possible to unilaterally default on the ECB, EU or the IMF.

By going through the debt numbers, we see that we brought €47 billion of debt with us into this crisis in 2008. Bailing out the banks will have generated around €47 billion of debt by 2015. The annual Budget deficits between 2008 and 2015 will have generated €99 billion of borrowings and we have borrowed €13 billion to build up a cash buffer.

If the country had avoided assuming the bad debt losses of the banking sector, the debt ratio in 2015 would still be around 90 per cent of GDP, which is better than 115 per cent but would not eliminate the fear of default because of the ongoing annual deficits. Of course, without the bank bailout we would also have a €20 billion sovereign wealth fund.

A negative outcome on any of the unknowns described earlier will increase the fear of default, but just because there is a lot of noise suggesting default is inevitable is not enough to mean it will happen. If the necessary steps are taken we can carry the interest burden of a debt of 115 per cent from 2015 and, in time, the debt ratio will fall. It will be painful but it can be done.

We don’t need to default on our debt but we may need some further assistance from the EU/IMF. To get through the end of 2015 the government needs to borrow €40 billion to fund its expenditure. The government also needs around €36 billion to roll over existing debt and pay the promissory notes. We need close to €76 billion of funding to see us from 2012 through to the end of 2015.

The EU/IMF deal will provide €34 billion of this. We need to raise an additional €42 billion, or around €30 billion if we use up our cash reserves. The official view is that we will return to the bond markets in late 2013 and begin raising this money then. With current yields on Irish bonds in the secondary market above 7 per cent it is still hard to see how we can raise this money sustainably from private sources. Market sentiment may improve as uncertainty about our situation dissipates, which would allow us to raise the money, but if that does not happen soon enough we will need additional support from the EU/IMF. We could achieve the funding target but if not I believe that this support will be provided because the programme can work.

If the option to default is to be taken, or default occurs because we have not arranged to have the required funding in place, those to suffer will be holders of Irish government bonds. It is more than a little incongruous that senior bondholders who invested in our delinquent banks are getting their money back while those who invested in our country may be forced to carry losses. As with a lot of things in this crisis, including unsupported claims of a €250 billion public debt, this just does not add up. I believe we can avoid that outcome and that we can stabilise our public debt. So this is my default story.