The Russian Crisis and the Crisis of Russia

Constantin is adjunct professor at the School of Business, Trinity College Dublin, and a director of St Columbanus AG, a Swiss asset management company. An internationally syndicated newspaper columnist, he blogs at trueeconomics.blogspot.com.

Introduction

In 1998, following some ten years of structural reforms that began during the late Soviet era under the perestroika process and continued after the collapse of the USSR, Russia recorded its first year of economic growth. The nascent middle class, starting to emerge in the country after the tumultuous years of early transition from the Soviet era, was enjoying what appeared to be the second year of rising disposable real incomes.

Then, with virtually no warning, by the end of August 1998, Russia found itself in a financial pariah state position, having defaulted on foreign-held sovereign debt, devalued its currency, imposed strict capital controls and bankrupted a large number of domestic firms and banks. A long-evolving sovereign crisis, having morphed into a fast-moving currency and banking crisis, had left deep scars on the socio-economic environment with middle-class savings either frozen in quasi-solvent banks or destroyed in their totality in dozens of fully insolvent smaller banks and investment funds. Foreign creditors – the lifeblood of an imports-dependent economy – were forced to write down their Russian assets as domestic banks suspended repayments of all external loans.

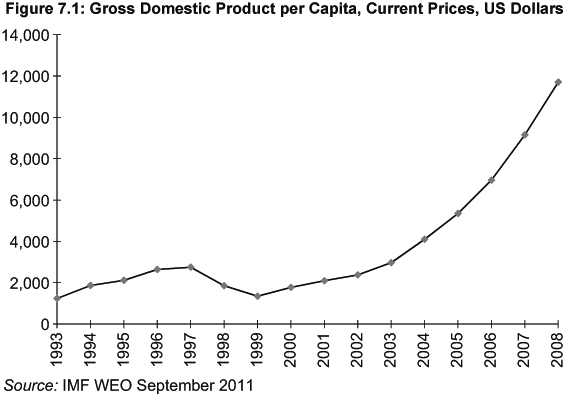

Despite the dramatic disruption caused by the crisis, the Russian economy staged an impressively swift comeback. The pain of the immediate crisis aftermath lasted a relatively brief period of time –approximately six to eight months – and the economy was able to rebound quickly and sharply. A decade-long economic boom followed the painful adjustments. During this time, the dollar value of Russian economic output increased ten-fold and the stock market rose more than twenty-fold to mid-2008. Devaluation triggered rapid structural rebalancing of the Russian economy and – helped by increases in oil and gas prices and general commodities inflation – by 2000, as shown in Figure 7.1, the economy not only recovered the losses triggered by the default, but also regained all of the ground lost since 1987–1988 reforms.

This process of recovery took a remarkably short period of time, with signs of emergent strengthening of the economy appearing in late 1999 and full macroeconomic recovery firmly established in 2000, less than one and a half years after the default. Russia returned to borrowing from the global markets within twelve months of its default, and booming exports-related revenues, along with prudent fiscal management and reformed tax policies, have resulted in the government repaying most of its debts in full, often ahead of schedule and in some cases even at a premium.

This historically unprecedented experience offers interesting insights and important lessons for the European crisis, and in particular for Ireland, as it highlights the overall importance of growth dynamics in determining the sustainability of a post-default or post-debt restructuring adjustment path. Although in the Russian case growth dynamics were driven by a combination of domestic and foreign factors not open to the Eurozone member states today, from the point of view of the impacted states with strong potential growth fundamentals, such as Ireland, the lessons from the Russian default present a hope for some significant upside potential for swiftly resolving debt overhang problems via a structured default. The Russian experience, however, also shows the importance of tangible and deep reforms in underwriting the process of recovery from the default.

In this context, let us first examine Russia’s road to default, and take a brief look at the adjustment and recovery path taken since 1999 through 2008.

The Roots of the Crisis: 1995–1997

The roots of the 1998 Russian crisis can be found in the events that start with the collapse of the USSR, when the Russian economy inherited all of the USSR’s debts and crumbling economic institutions and structures. This little known fact, often omitted from the discussion of the role of Russia in the post-Communist economic transition in the broader Central and Eastern Europe and Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) regions, nonetheless serves as the departure point for the analysis of Russia’s fiscal policy dynamics in the 1990s.

In April 1996, Russia began a series of international negotiations aimed at rescheduling the repayment of foreign debts inherited from the USSR. Until then, the Russian economy was saddled with the massive burden of covering $100 billion of debt that it assumed following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Overall, upon dissolution of the USSR, Russia assumed the entire foreign external debt of the Soviet Union despite the fact that Russia accounted for less than half of the total population of the USSR and for approximately 50 per cent of its national income. The level of debt carried by Russia from the USSR was equivalent to 117 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 1992. According to Nadmitov:1

This level of debt was too heavy for a transitional Russian economy that needed further financial injections [in order to finance investment and transition]. The combination of a fall in output coupled with the fiscal costs associated with the transition made the scheduled debt service a significant burden. For ten years between 1991 and 2001 Russia reached six multilateral debt rescheduling agreements with official creditors, [and] held five formal debt relief and principal deferment negotiations with commercial creditors ….

Thus, from the Russian perspective, the 1996 re-negotiations of sovereign debt were a major move in the direction of stabilising the economy.

At the same time, late 1995 and 1996 were marked by improvements in the trade balance. Although the rate of growth in exports of goods and services declined slightly from 7.7 per cent in 1995 to 6.8 per cent in 1996, both years posted well above average increases in export volumes for the entire post-USSR period. At the same time, the rate of growth in imports of goods and services had fallen from 17.7 per cent in 1995 to 6.2 per cent in 1996, marking the first year since the transition began when the growth in exports was exceeding the growth in imports. At the same time, exports of oil rose from $14.6 billion in 1994 to $18.3 billion in 1995 and $23.4 billion in 1996. The heavy dependency of Russia on imports was itself the legacy of the Soviet Union economic organisation, which favoured specialisation across individual republics and between the member states of the COMECON (the common trade area of the former Warsaw Pact) block. Restructuring of this specialisation was always envisioned as a painful and long-term process, which was further disrupted by the mismanagement of trade flows upon the dissolution of the USSR.

Russian GDP in nominal terms rose from $276.9 billion in 1994 to $313.5 billion in 1995 and $391.8 billion in 1996. With slowing inflation (down from 215 per cent in 1994 to 21 per cent in 1996), real economic growth improved from -12.7 per cent in 1994 to -3.6 per cent in 1996. 1997 became the first year in the post-Soviet period when Russian real GDP actually expanded, achieving 1.38 per cent growth year on year. Inflation came under much stricter control at 11 per cent and by the end of 1997 Russian nominal GDP rose to $405 billion.

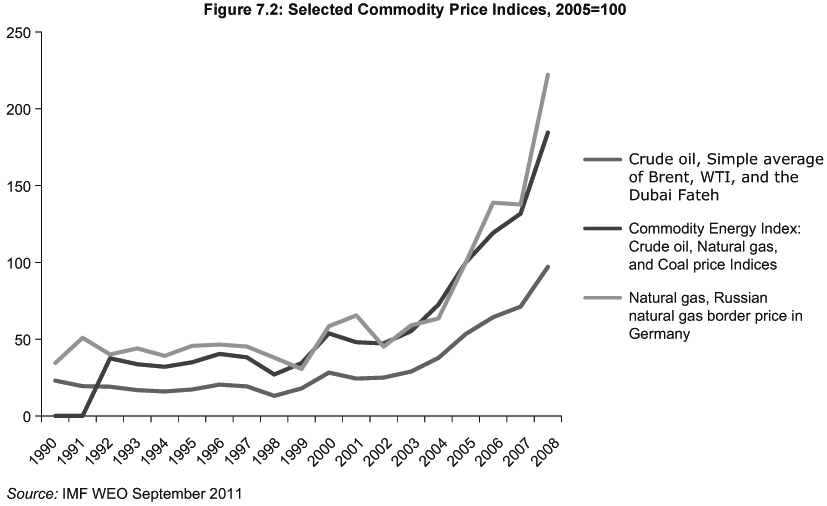

To a large extent, this effect was driven by improved volumes of exports of energy (oil and gas) and other primary materials. As illustrated in Figure 7.2 (index of prices for natural gas), Russian deliveries to Europe firmed up from 39.1 in 1994 to 46.5 in 1996 – the highest level since 1991. Average crude oil prices, which had stood at $15.95 per barrel in 1994, rose to $20.37 per barrel in 1996, also the highest price achieved in five years. Wheat, barley and cereal prices also posted decade highs in terms of prices in 1996, as did tin and nickel. Although energy accounted for 45 per cent of Russian exports by 1997, the overall exports of goods and services were on an improving trend in 1994–1996 and through the first half of 1997. While the legacy debt of the USSR was now close to the sustainable levels, the financing costs required to maintain the government debt remained high.

Russia entered the April 1996 negotiations on debt reduction with the Paris and London Clubs of borrowers – two international arrangements representing large groups of sovereign and private lenders – with its economic performance finally starting to show some signs of life after six years of rapid decline. These transitional years followed two decades of Soviet-era stagnation and economic decay. The analysts’ consensus on the Russian economy and fiscal conditions between 1996 and 1997 was, thus, favourable. This change in the outlook was a marked departure from the preceding decades. At the conclusion of these debt talks in September 1997 Russia agreed rescheduling the repayment of some $60 billion worth of ex-Soviet debt with the Paris Club. In October 1997, Russia rescheduled repayments on $33 billion of debts to the London Club. As a part of these agreements, Russia lifted the restrictions on foreign holdings of its sovereign bonds. By the end of 1997, foreign residents held almost one third of all state-issued short-term bills (GKOs).

The Blow Up: 1997–1998

Improved international ratings and subsequent gains in access to international lending markets, however, were not reflected in a matching improvement in the federal government’s fiscal performance. Tax collection remained endemically mired in corruption, and harmful regional and federal competition; and the black markets continued to expand.

In addition, based on improving credit ratings, Russian banks aggressively courted foreign funding, with the ratio of foreign liabilities to assets rising from 7 per cent in 1994 to 17 per cent by the end of 1997. Exacerbating this growing risk exposure, the majority of investment contracts held by foreign investors in Russian banks (some $6 billion in total) were short term and held off balance sheet.

This meant that while on the surface the Russian economy was at the starting line for economic recovery, by late 1997/early 1998 a number of structural weaknesses were present behind the scenes. Improved access to external funding coincided with continued declines in private investment: between 1994 and 1997 total investment in Russian economy dropped from 26 per cent to 22 per cent of GDP. Increases in official and banks inflows masked even more pronounced declines in private foreign direct investment (FDI). In addition to endemic tax collection problems, rising unemployment (up to 10.8 per cent in 1997 from 7.2 per cent in 1994) contributed to shortfalls in government revenues. By the end of 1998 general government net borrowing was running at 8 per cent of GDP, the structural deficit widened in 1997 to a massive 16.3 per cent of GDP, and general government debt was on track to hit 100 per cent of GDP in 1997–1998. Wages backlogs exceeded 40 per cent of payrolls by 1997 and tax evasion, including by ordinary workers, was rampant.

Much of the economy remained captured by extraction sectors, with imports of goods rising 11.6 per cent year on year in 1997, while exports of goods were shrinking 1.05 per cent. Agriculture and food, and consumer goods remained particularly weak domestic sectors. By 1997, virtually every shelf in the average Russian supermarket was occupied by imported foodstuffs. Where domestic producers attempted to compete with branded foreign consumer goods, this competition almost invariably took place at the lower end of the value-added spectrum.

The lack of diversification in the Russian economy was caused by a combination of two factors. Firstly, the break-up of the Soviet Union and, equally importantly, the COMECON trading block exposed the Russian economy to a simultaneous loss of some markets for its output and a tightening of supply of consumer goods. Russia’s energy, chemicals and heavy industry specialisation within the USSR has led to a de facto de-diversification of its economic activities. There were significant supply disruptions to Russian industry from the former COMECON member states, in effect shutting down production of internationally marketable heavy industrial equipment, aircraft and other goods traditionally specialised in by the Russian economy. Secondly, Russia’s development since its 1991 independence from the USSR saw an increasing domestic and foreign capital push toward investment in oil and gas, as well as other extraction industries. Much of the economic policy at federal level reflected this development, especially since tax competition between federal authorities and local governments in the area of corporate tax revenues left the federal state budget more exposed to dependency on exports revenues from oil and gas sales. This further incentivised significant policy biases in favour of extraction sectors between 1993 and 1997.

The economic unravelling began in the foreign exchange markets in the last quarter of 1997 when, following the Asia Pacific currency crisis, the Russian ruble came under sustained devaluation pressures. By late November, the ruble was sustaining a deep speculative attack, just as the oil and gas prices began to moderate, signalling a twin currency valuation and currency demand crunch. Ruble overvaluation was sustained on the basis of the core government objective to keep inflation under control. Within just one month – in December 1997 – the Central Bank of Russia was forced to incur foreign exchange reserve losses of some $6 billion trying to defend the ruble. The problem was further exacerbated by the structure of the short-term bills (GKOs) issued by the Russian government, which contained an explicit hedge against ruble–dollar devaluation. This proviso was a direct outcome of the poor quality of expert advice Russia received from the international lending bodies, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank.

Inflationary control measures coincided with a defence of the overvalued ruble throughout most of 1998. The Central Bank of Russia attempted not only to deploy open market operations to sustain ruble valuations, but also increased the lending rate – the rate at which the Central Bank lends short-term funds to registered banks – from 2 per cent to 50 per cent in early 1998. With the developments in the Asian currency crisis in the background, in December 1997 the IMF re-launched loans disbursement to Russia, with a loan of $700 million. At the same time, the IMF urged Russian authorities to close the fiscal deficit gap in part by improving tax revenue collection.

Sustained pressure on the ruble accelerated into 1998 as it became increasingly apparent that economic growth would not reach the 2 per cent budgetary assumption. Tax reforms in February 1998, aimed at streamlining tax codes and improving tax collection, came in too late to reassure foreign investors that the Russian government’s deficits were on a sustainable path. According to analysts, the Russian federal tax system of 1992–1999 was:

… characterized by extreme instability, complexity, and uneven distribution of tax burden, weak administration, low competitiveness and poor transparency. High rates of income and profit taxes were ones of the biggest business development disadvantages and because of weak administration of these taxes; they created the background for the shadow economy.2

The February 1998 reforms proposals were put in place primarily to alleviate IMF concerns regarding fiscal sustainability and to allow the IMF to extend its loans to Russia by one year. But the reforms, favoured by the Yeltsin administration, were not supported by the broader political establishment. The reforms did run into trouble in the State Duma (the lower house of the Russian Parliament), which briefly suspended hearings on their adoption in July 1998. The version of tax reforms that was finally approved on 16 July failed to commit to implementing the full $16 billion in tax revenue measures, as the State Duma scaled back President Yeltsin’s proposals for higher sales taxes and land value taxes. In line with Duma approval, the IMF announced $23 billion worth of emergency loans to the Kremlin on 13 July 1998, well in excess of the normal special drawing rights (the unit of IMF capital-determining currency) allocations allowed.

Even before this disbursement took place, the Russian government had repeatedly tried to secure IMF funding since late March 1998. As financial conditions continued to deteriorate through the end of the first quarter of 1998, President Boris Yeltsin took a series of steps attempting to bring under control the twin economic and political crises. On 23 March 1998 he unexpectedly dismissed the entire Cabinet, sacked Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin, and appointed the heretofore unknown 35-year-old Sergei Kiriyenko as the head of government. Kiriyenko’s inexperience in the federal political structures proved a fatal error. The new prime minister’s first political appointment took place in 1997 when he was given the portfolio of the First Deputy Minister for the Fuel and Energy Sector. Thus, prior to his appointment as Prime Minister, Kiriyenko had less than twelve months’ experience in government and no direct experience in federal politics, and came from a corporate background.

The appointment of Kiriyenko as the country’s prime minister acted to further destabilise the already fragile political balance between Yeltsin and the State Duma, as well as between the federal state and regional authorities. It took Yeltsin until 24 April to finally secure Duma approval of the new prime minister and even that required forceful threats from the President to the parliament, including the threat of dismissal.

Kiriyenko showed his lack of experience when in a public interview he stated that Russian federal tax revenues were running 26 per cent behind targets. Instead of directly and transparently promoting government budgetary plans for reduced deficits, Kiriyenko made a bizarre statement that the federal government was, at that point in time, ‘quite poor‘. Kiriyenko’s public gaffe reinforced an already growing public perception that the ruble was to be devalued against the US dollar – the preferred store-of-wealth currency in Russia in the 1990s. In May 1998, Sergei Dubinin, chairman of the Central Bank of Russia, made another public statement that referenced the possibility of the Russian government facing a full-blown debt crisis between 1998 and 2000. Both Kiriyenko’s and Dubinin’s statements added fuel to the fire of speculative attacks betting on a ruble devaluation and rapid withdrawals of funds from Russian banks. Both represented the degree of policy incoherence that characterised the later period of Yeltsin’s administration. Both were newsworthy items in markets already stressed by the continued Asian currency crises.

Selling pressures on Russian GKOs accelerated. It is worth noting that GKOs were accumulating in the hands of large institutional investors with a significant appetite for risk. In addition, these instruments were also held on banks’ balance sheets. With GKO prices collapsing, foreign investors began aggressively deleveraging out of the GKOs. However, the same did not take place in the Russian banking sector, with Russian banks continuing to accumulate GKOs in a speculative bid to boost profits, while simultaneously relying on the sovereign nature of these bonds as a ‘guarantor’ of their safety. Deleveraging by foreign investors was met by the Russian treasury with increases in the short-term yields on reissued GKOs and by May 1998 government bond yields had reached 47 per cent. Only then did the Russian banks enter the process of gradually reducing their exposures to the new debt issuance and even then the Russian banks’ deleveraging out of GKOs was slow and mostly concentrated among a handful of medium to large banks exposed to international banking services competition.

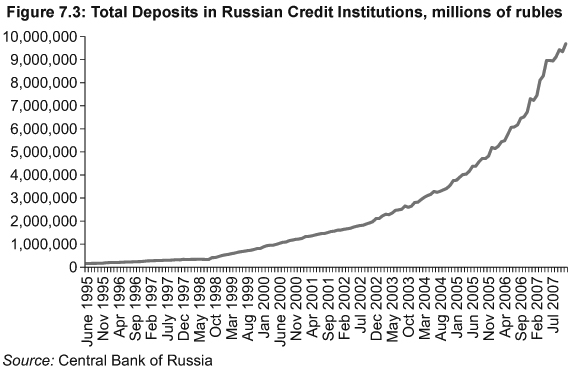

Meanwhile, retail deposits started to dry out as domestic savers switched into hoarding cash. Demand for dollars rose both externally and internally, since the US currency served as the main store of value since the late Soviet era. Capital expatriation rose dramatically. Between 1997 and 1998, growth in ruble deposits by Russian residents fell from 30 billion rubles per annum to 1.3 billion rubles per annum, despite the fact that the money base continued to expand as shown in Figure 7.3.

The deleveraging was amplified by the aggressive drive by the Russian authorities to improve tax revenue collection. As part of the tax reforms back in 1997 Russia had created a much more effective and less corrupt treasury system which was modelled on a similar system already in operation in the city of Moscow. The agency concentrated its efforts on the extraction industries with access to foreign currencies. Unfortunately, these sectors were also heavily reliant on imports of capital equipment to sustain their production growth. Many exporting firms, pushed to the limit by federal tax collectors, were suspending payments on equipment purchasing contracts. As the price of oil, and to a lesser extent natural gas, continued to trend downward, reaching $11 per barrel in May 1998, many voices within the corridors of power were speculating about the need for drastic devaluation of the ruble. These rumours helped to push up the risk premiums on Russian GKOs in the international markets and precipitated rounds of foreign exchange hoarding by exporters and Russian banks. As the result, the domestic banking system was effectively split into two, with foreign-trade-engaged larger and state-owned banks running hard currency balance sheet operations to hold increasing reserves of foreign liquidity, and smaller domestic savings banks becoming completely exposed to ruble valuations. As the Central Bank of Russia continued to pump billions of dollars into foreign exchange markets in a futile attempt to defend the ruble, the former group of banks became extremely important to the Russian federal authorities, in part ensuring that following the default these banks will be taken into state ownership and preserved. Meanwhile, purely domestic banks in the second group were clearly falling out of the market operations and becoming less important to the Central Bank in its crisis management mode, thus ensuring their eventual bankruptcy post-default.

The structure of taxation was decisively shifting away from supporting capital investment and in the direction of reducing tax credits available to businesses and banks. For example, 1998 tax reforms included a cancellation of the practice whereby government departments and ministries, as well as state-owned enterprises, issued tax credits in payment for private sector supplies of goods and services.

Even with these draconian changes, the federal government was able to increase tax collection only marginally to approximately 10 per cent of GDP. Meanwhile, the budgetary performance was going from bad to worse. In 1997 the deficit reached 6.1 per cent of GDP and the government hoped to reduce it to 5 per cent in 1998. However, two factors underpinning these plans never materialised. Firstly, the deficit target for 1998 was based on assumed growth of 2 per cent in real GDP, while real growth came in at a contractionary -5.35 per cent instead. Secondly, Budget 1998 was computed on the basis of the highest interest rates on government debt of 25 per cent. By mid-1998, interest rates stood at six times that, implying that debt servicing consumed over half of government revenues. The end result was a fiscal deficit that reached 7.95 per cent of GDP in 1998.

By the end of May 1998, demand for GKOs began to collapse with yields rising to over 50 per cent and weekly bond auctions failing to attract sufficient numbers of bidders to allow for the full allocation of bonds in the market. This put pressure on the government that required an ever-increasing frequency of issuing new bonds to roll over the existent debt. Shrinking demand for GKOs was thus met by dramatically growing supply of these bonds. The Central Bank of Russia continued to hike lending rates, reaching 150 per cent. Dubinin attempted to calm devaluation fears by saying, ‘When you hear talk of devaluation, spit in the eye of whoever is talking about it.’ Russian asset markets reflected the fate of the GKOs with markets experiencing massive sell-offs. On 18 May the Russian stock market registered a 12 per cent drop, and in the first six months of 1998 stocks were down 40 per cent on 1997 levels. These developments prompted James Wolfensohn, the head of the World Bank, to declare the Russian market to be in crisis and the Chairman of the Russian Securities Commission to respond with a statement that the market’s situation was ‘nothing other than a crisis’.

By June 1998, Central Bank interventions in the currency markets were draining $5 billion of reserves as Russia headed toward a September deadline for the redemption of billions of dollars’ worth of ruble- and dollar-denominated corporate and government debts. A July 1998 IMF assistance programme injected $4.8 billion in funds designed to shore up the collapsing GKO markets, with an additional $6.3 billion committed for later months. Yet, in the very same month, capital outflows from Russia, Central Bank interventions and declines in oil and gas revenues due to falling prices shrunk the money supply by approximately $13 billion. Even with that, IMF funding was clearly not going to come at the rates required to buy significant time. Overstretched by the funding requirements of the Asian currency crises of 1997–1998, the IMF had to dip into emergency credit lines itself – something it has not done since 1978 – to find money to finance the first tranche disbursal to Russia. This did not go unnoticed by foreign investors who accelerated their selling of GKOs and other Russian assets following the IMF announcement.

The 13 August stock market crash of 65 per cent precipitated the end of the Russian government’s efforts to defend the ruble. Following the stock market crash, GKOs yields rose to over 200 per cent. On 17 August 1998, the Russian government enacted drastic devaluation, froze domestic bank accounts and declared a moratorium on debt repayments to foreign GKO holders, while fully defaulting on domestically held debt. Commercial accounts in the banks were frozen for 90 days and many companies ended up losing all their deposits and payment streams as dozens of banks went bust virtually overnight. On 24 August the government fell with Prime Minister Kiriyenko dismissed by Yeltsin, and on 2 September 1998 the Central Bank abandoned interventions in the foreign exchange markets, allowing the ruble to float against all currencies.

Post-Crisis Recovery

According to Moody’s research,3 the Russian default – $72.71 billion – accounted for over 96 per cent of the total worldwide default volume of $76 billion in 1998. The event constituted the second largest default (after Argentina’s $82.27 billion default in November 2001) over the entire period of 1998–2006. Furthermore, according to Moody’s, the Russian default was associated with the lowest recovery rate (18 per cent) of all defaults over this period. Following the August 1999 and February 2000 restructurings debt burdens overall fell to a more sustainable level of 59.9 per cent of GDP in 2000, down from 99 per cent in 1999. The appointment of a new government, with Viktor Chernomyrdin returning as Prime Minister, was the first stage of the stabilisation. Chernomyrdin had served as Prime Minister in 1992–1998, a period that taught him some core lessons. Firstly, that ruble devaluation was inevitable and losses of foreign reserves cannot be sustained without destroying the economy. Secondly, the political balance between the Duma and the presidential administration was a precondition for success of longer term reforms. And thirdly, that the state finances had to be scaled back on the expenditure side in order to unwind accumulated internal debts.

However, Chernomyrdin’s second tenure did not have the full backing of Yeltsin, who was battling for his own political survival. The Russian economy ended 1998 with GDP down 5.345 per cent in constant prices and the country’s GDP fell from $404.9 billion in 1997 to $271 billion in current prices in 1998 – a level that threw Russia back to its 1993–1994 average. Devaluation pushed domestic inflation to 84 per cent, primarily impacting imported goods. Crucially, Chernomyrdin failed to win over the Duma and enact any significant reforms.

At the same time, a 75 per cent devaluation of the ruble helped push Russian exports. The Russian current account posted a deficit of 0.02 per cent of GDP in 1997 and by the end of 1998 was running at a surplus of 0.08 per cent. In 1999 the external balance of the Russian economy rose to a massive 12.6 per cent surplus, and thereafter, in 1999–2008, current account surpluses averaged 10.1 per cent of GDP per annum. If in 1998 Russian economy’s trade balance contributed roughly $219 million, by the end of 1999 the same figure stood at $24.6 billion and by 2008 it rose to $103.7 billion. In the early post default years much of the economic recovery was attributable to a decline in consumer imports and the subsequent rapid substitution of domestically produced goods for foreign imported goods. After 2002, rapid increases in oil and gas prices helped to accelerate current account growth momentum. However, monetary and fiscal policies also helped. The transition of power from Boris Yeltsin to Vladimir Putin on 31 December 1999 ushered in a completely new era of political stabilisation (although this was achieved at the expense of rolling back some of the reforms established under previous rounds of democratisation in 1991–1997) and a focus on some core structural reforms.

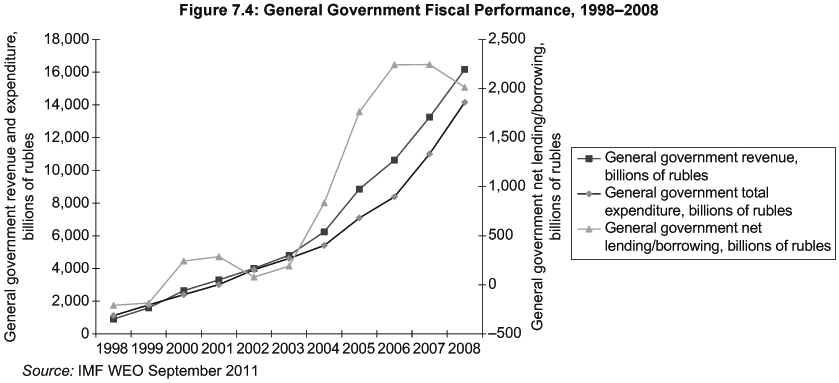

In particular, the new administration moved swiftly to address Russian fiscal deficits, as illustrated in Figure 7.4.

This was achieved in three core steps. Firstly, the Russian state implicitly recognised the inability, at least during the recovery stage, to finance a significant extension of the welfare state beyond its core functions of supporting education, basic health and limited social welfare. This led to the renewed push toward a reduction in public spending and rationalisation of budgetary allocations.

Secondly, the government dramatically improved its enforcement of tax collection and set rapidly on course to restrict tax competition from the regions. Rolling back excessive autonomy granted to the regions by Boris Yeltsin, Vladimir Putin managed to dramatically lower federal tax revenue slippages due to regional authorities’ corruption and collusion with private enterprises.

Thirdly, in 2001 the government launched ambitious tax reforms which saw a reduction in the overall tax burden on individual incomes, streamlining compliance and, once again, beefing up enforcement. A progressive personal income tax system that imposed a range of tax rates between 12 per cent and 35 per cent was reformed into a flat tax system with single rate of 13 per cent. Between 2000 and 2001 income tax revenues increased from 175 billion rubles to 256 billion rubles, a rise of 46 per cent in just one year. The annual rate of growth in income tax revenues for 2000–2004 hit almost 35 per cent and the overall share of income tax revenues in the overall government revenues rose from 8.3 per cent in 2000 to 10.6 per cent in 2004. In addition to reforming personal income tax rates, the Putin administration also reduced the headline corporate tax rate from 35 per cent to 24 per cent in 2002. The initial impact of this change was to reduce corporation tax revenues in 2002 from 514 billion rubles in 2001 to 463 billion rubles in 2002. Boosted by economic growth and the reduced burden of compliance, as well as by the improved enforcement of tax codes, corporation tax revenues rose to 868 billion rubles in 2004. Reforms of tax codes and the lowering of the corporation tax rate also explain the rapid expansion of investment in the economy. In 2002 the inflow of FDI into Russia amounted to $4.0 billion. This increased to $9.4 billion in 2004.

Russia was able to access funding markets relatively quickly post-default, as was the general experience with defaults in the 1990s. Gelos et al.4 found that for defaults that took place in the 1990s the average return to funding markets took 3.5 months, as opposed to 4.5 years for defaults during the 1980s. However, in the case of Russia the return to the markets initially was a costly one with 2003–2005 bond spreads remaining above 200 basis points, despite the fact that the country was showing very robust rates of economic growth and double digit surpluses on its current account. This is most likely related to three factors. The Russian default, as noted above, was characterised by extremely low rates of recovery on government bonds. In addition, most of the Russian government debt pre-default was held by foreign investors, implying a much more significant impact on foreign bondholders. Lastly, the Russian economic recovery was perceived to be primarily driven by rising oil prices – a perception that is well grounded in reality.

The immediate disruption caused by the default and the currency crisis was painful. Unemployment rose from 10.8 per cent in 1997 to 13.0 per cent in 1999 – the peak of official unemployment for the 1990s. In some areas, especially in industrialised central Russia, the collapse in investment led to the effective shutting down of industrial production. In many regions unemployment reached 18–20 per cent, and these numbers concealed the fact that, in addition to massive jobs losses, many in employment saw their wages delayed. Payments arrears and a stalled banking system meant that backlogs of wages rose to 50–60 per cent in cities such as Nizhny, Novgorod and Penza. Moscow itself weathered the storm much better due to more efficient payments systems and the city’s government’s more proactive stance on payments to its employees.

The crisis materialised at the time when many Russian industries were at the tail end of the process of realisation that state orders and older patterns of production, reliant on government and military orders, were coming to an end. This meant that many impacted enterprises, especially the larger ones, were already on the cusp of transitioning to more market-driven economy. The crisis accelerated this process. The collapse of the ruble in 1998 improved the competitiveness of domestic products and services. As imports prices quadrupled virtually overnight, domestic industrial and agricultural output increased. For example, within two years of the crisis, unemployment in one of the core industrial regions – the region of Penza – fell from 18 per cent to 1.5 per cent and industrial output grew by 141 per cent. Remonetisation of the economy following the ruble devaluation provided the necessary liquidity to pay down salaries and wages arrears and consumer spending rose by late 1999. The government policy of centralisation of authority away from a regional distribution of power – the default option pursued by the Yeltsin administration – also helped. The Kremlin forcefully re-asserted central control over the regions and this political move was backed by Moscow’s efforts to repay regional governments’ debts to state employees. Within three years of default, the demand for skilled workers rose and the Russian middle class regained all income and savings losses sustained in the crisis.

One feature of the Russian crisis was the collapse of the banking system. The banking crisis in the Russian case was driven by a number of factors related to the broader problems in the Russian economy. During the early 1990s, Russian industrial enterprises set up a number of their own banks for the purpose of enhancing internal control of their capital and using industrial funds to earn additional income from lending. By 1996–1997, however, the system of credit in the country had firmly shifted away from lending to enterprises and was more geared toward booming domestic credit and government securities. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD),5 by the end of 1997 the commercial banking sector held almost 75 per cent of ruble-denominated deposits in form of federal government debt. At the same time, OECD data suggested that private sector credit fell from 12 per cent of GDP in 1994 to 8 per cent in 1997. High interest rates and banking sector inefficiencies have meant that large segments of the Russian economy were operating on informal credit and barter.

Following the default, remonetisation of the economy has meant that black market credit and payments transactions, especially those involving barter, have declined. This decline was almost immediate, as noted in Huang et al.,6 who show that barter and non-cash payments fell 20 per cent in 1999 and continued to decline in importance in 2000 and 2001. Subsequent tax reforms streamlining personal and corporate income taxation measures and compliance added further strength to the process of normalisation of the Russian payments systems.

The consolidation of the banking crisis post-default and the collapse of overall government asset markets meant that the banks were incentivised to start lending to the real economy. Between 1998 and 1999, the volume of ruble loans rose from 123 billion rubles to 293 billion rubles. The volume of total loans rose from 310 billion rubles in 1997 to 597 billion in 1999 and 1,418 billion in 2001.

The consolidation of the banking sector saw three core state-owned banks capturing some 80 per cent of the liquid banking assets in the country – a move that instilled more confidence in the banking system’s stability within a population that lost all trust in private banks during the default. According to Huang et al., the collapse of the assets acquisition conduit via government securities meant that surviving banks were forced to seek new assets in the commercial lending markets. The cost of credit therefore declined and many enterprises were able to access new credit. The virtuous cycle of improving credit ratings for many enterprises, spurred on by robust economic growth in 2000–2002, was reinforced by these developments in the banking sector. Reversal of the capital flight out of Russia, in part largely predicated on capital controls imposed during the crisis, also helped.

The banking sector collapse and ruble devaluation have significantly reduced the overall dollar equivalent volumes of household deposits. In June 1998, total household deposits stood at around $40 billion. This number fell to $12.1 billion by December 1999. Likewise, capital controls have meant that many commercial creditors were made insolvent almost overnight. As reported by Euromoney,7 a World Bank study found that in 1999 the majority of losses within the banking system in Russia were driven by commercial loans, not the government assets bust. Specifically, loan loss provisions amounted to $64.3 billion in 1999 and 34 per cent of net charges to banks’ capital. Losses on government assets were only 13 per cent.

These processes crystallised losses on banks’ balance sheets and forced significant reforms of the banking sector, including much tighter supervision and stricter lending rules. But the main thrust of reforms was the significant reduction in cross-ownership of banks by industrial companies in the private sector. In the early 1990s, large number of banks was created within the industrial groups that were privatised during the Yeltsin era, and especially during loans-for-shares schemes. These banks acted as conduits for industrial oligarchs’ access to government lending arbitrage. The banks borrowed cheaply from the Central Bank of Russia and rolled borrowed funds into GKOs. Some of these loans were used to further increase industrial companies’ access to capital that was used to finance purchases of state-owned assets in extraction sectors and finance bidding for lucrative licenses. Post default, a large number of these banks went bust and the remaining ones were consolidated in super-sized commercial banking entities, such as Gazprombank. This consolidation, and state backing for the larger banks, has meant that domestic depositors, including retail savers, improved their perceptions of the banking sector in general. A deposit insurance scheme also backed by the state that was put in place in December 2003 further reinforced this build-up of confidence. The result was an increase in deposits that continued unabated from 1999 through the period of post-crisis shock.

Conclusions

Overall, Russian experiences in the post default adjustment reveal a number of important lessons for the peripheral countries of the Eurozone that are witnessing a similar crisis today.

Rapid recovery from the default is possible, even when such a default takes place without proper planning and contingent hedging, under favourable external conditions. Reforms, especially structural reforms of market institutions related to the underlying causes of the crisis, promote long-term growth and recovery and do contribute positively to the defaulter’s ability to return to funding markets within a short period of time. Furthermore, these positive aspects of post-default recovery are reinforced for countries with no past history of defaults. Disruptions to normal functioning of the banking system and economic transactions in the short run represent one of the two core downside factors in the default scenario. The other is the significant reduction of real savings levels due to bankruptcies and devaluations of banks. Both of these factors require serious contingency planning and the creation of systemic responses that can help mitigate their adverse impacts on the overall economy. However, as experience in Russia shows, even extremely painful after effects of the default, such as a collapse of private savings, can be effectively mitigated by aligning fiscal reforms with the objectives of helping adversely impacted households to rebuild their savings and wealth. In Russia this was achieved through robust repayment of accumulated government liabilities toward state pensioners and employees, as well as through the creation of a benign personal income tax environment combining low rates of income taxation and a flat tax system of income tax. Lastly, in the case of Russia, the default on sovereign debt can be seen as a catalyst for real and sustainable long-term reforms of the economic institutions. While this process is far from complete, the Russian economy performance since 1998–1999 has been impressive.

Endnotes

1 Nadmitov, A. (2004) ‘Russian Debt Restructuring: Overview, Structure of Debt, Lessons of Default, Seizure Problems and the IMF SDRM Proposal’, paper presented at the International Finance Seminar, Harvard Law School, available from: <www.law.harvard.edu/programs/about/pifs/llm/sp26.pdf>, pp. 5–6.

2 Krivka, A. (2006) ‘The Experience of Russia in Reforming Tax System: Achievements, Problems and Perspectives’, Vaduba Management, Vol. 2, No. 11, pp. 73–74.

3 Moody’s Investors Services (2007) ‘Sovereign Default and Recovery Rates, 1983–2006’, Global Credit Research Note, June.

4 R.G. Gelos, R. Sahay and G. Sandleris (2004) ‘Sovereign Borrowing by Developing Countries: What Determines Market Access?’ IMF working paper no 221, November 2004.

5 Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (1997) OECD Economic Surveys: Russian Federation 1997, OECD: Paris, 1997-19.

6 H. Huang, D. Marin and C. Xu (2003) ‘Financial Crisis, Economic Recovery and Banking Development in Former Soviet Union Economies‘, CESifo working paper no. 860, February 2003, available from: <http://www.ifo.de/portal/pls/portal/docs/1/1189878.PDF>.

7 Euromoney (1999) ‘Russia, The Newly-Wed and the Nearly Dead’, 10 June, available from: <http://www.euromoney.com/Article/1005258/Russia-The-newly-wed-and-the-nearly-dead.html>.