At first, success is in the writing of poems. Questions like “Is this a good poem?” come later. That way, you learn with freedom and curiosity how to do a new thing.

After a while, I’ll bet you will begin to want to know which of your poems are strongest and come closest to being whole and authentic, free from the need to explain a thing. At that point, you’ll be ready to bring them into the world, in whatever ways suit you best.

In the next chapter, on editing and revision, we’ll dive into what makes a poem work. But for now, let’s think about the idea of success and failure. Look at “the making of poems” by Lucille Clifton.

the reason why i do it

though i fail and fail

in the giving of true names

is i am adam and his mother

and these failures are my job.

To view failure as what a poet is supposed to do—to consider it part of one’s job—is counterintuitive. We tend to think not only that failure is a hindrance to success, but that it’s bad—or worse, that we are bad when we don’t succeed. Of course, success is what we strive for, and to get there, we should avoid failure at all costs, right?

Ever since I heard Clifton read this poem, her voice, particularly when she got to the pronouncement at the end—“these failures are my job”—has lived in me and offered comfort. It helps me to be more accepting of the truth of the writing experience. To become a strong writer, you have to try things out and to dare.

There will be many false starts, a lack of clarity and precision in your language, unintentional redundancies, poems that start off strong but fizzle out. You’ll write poems that will stall or fall flat on their pretty poetic faces. Then comes the subsequent deleting or ripping to shreds, or fireplace burning, of work that dead-ends, that sadly goes nowhere.

But wait: all of your poems are going somewhere! Keep in mind, every poem you write increases your skill; each poem helps you hone your vision, develop your style, refine your chosen subject matter, take creative leaps, and learn to trust your imagination.

When I get frustrated with writing—at being unable to say the thing I want to say—my husband will remind me, “You’re not digging a ditch, you know.” If you have a shovel and a plot of dirt that needs digging, and your body is strong, it’s straightforward hard work. By day’s end, you’ll be tired and may have blisters, but, hopefully, some money and a cold drink too (and a nice deep ditch!). Creativity can be fickle. It can be complicated. It’s easy to lose a train of thought, to write yourself into a corner.

To invest in your writing, you have to give it the time it needs when it’s easy and when it’s hard. Here’s a story about Lucille Clifton. She came to Santa Cruz to give a reading when she was elderly and not physically strong. Before the crowd, the content of her work was as strong as ever, but her voice, though beautiful, had lost some of its force.

Partway through the reading, a man in the audience yelled out, “Speak louder, please.” Even from the back of the room, I could see the fire in Clifton’s eyes. Leaning forward, she said, “Listen harder!” Oh, such beautiful fury!

I tell you this story now because it’s the attitude that will support your writing through your successes and failures. When you get frustrated because your writing is off the mark, and you want to say to yourself, “Write better,” instead do what Clifton did: stand firm and determined, confident. You will find your way.

57. Making Your Words Stick to the Page: The Editing Process

After writing a poem, I put it in an actual or an imaginary drawer for a while. I want the words to get to know each other in the arrangement I’ve given them. Will they become allies? Or are they going to tear each other up, so that when I go back for the poem I’ll find only paper shards?

Getting some space from the poem allows me to see it more clearly, as separate from myself. Turning back to it, I become not only its writer but its first reader.

Here’s what I look for: Does the poem make something happen in my body? Does it startle or cause tears to come to the edges of my eyes? Make me angry, poem! Make me fall in love. A poem that causes me to think anew, or that reminds me of something important I’d forgotten, is the poem I want to read. Look at a handful of favorite poems that others have written. What draws you in and holds your attention? Is it the unexpected subject matter? The imagery the poet uses? Make a list of the qualities that get to you.

Next, look at your own work. Does it have the same qualities? What does your work need to do to be moving or subtle or edgy, or whatever you’re after?

When it comes to editing, I always read the poem aloud. When I do that, at some point along the way, a buzzer in my head may go off. So, I reread the line that caused that awful noise. If it goes off again, that indicates something in the line is off. That buzzer is spot-on in informing me of when I’m being disingenuous or unclear. It informs me the poem needs more work.

I may read it to a trusted someone. Because it’s not their poem, they may be able to see it more clearly than I can and tell me what’s not working. I have notebooks of lines that I’ve reluctantly deleted from poems, to keep for a rainy day.

My goal, before I call a poem complete (knowing that a poem is a malleable thing that I may want to revise again later), is to be able to say “yes” to every single word and its relationship to every other word. This line, attributed to William Stafford, describes what we might all strive for in our poems: “If one part were touched, the whole would tremble.” Have you ever touched a spider’s delicate web and noticed how that’s exactly what happens?

That trembling comes because there’s a relationship between all the parts of a finished poem. A strong poem equals more than the sum of its components. For the writer, and later the reader, to be moved by a poem, the language needs to resonate emotionally. For this to happen, a kind of magic needs to occur that allows writing to go beyond the intellect. I see it as welcoming the spirit in. Be sure, when editing your writing, that you don’t edit the magic out.

Years ago, I wrote a poem while staying in a cabin alone, in Desolation Wilderness, California—no phone, no electricity, no car, only a rowboat (that I couldn’t adequately row) to get around Echo Lake. Each day, I hiked for miles into the granite, and each day, I wrote. One day, this line came to me: “It is so quiet my mother could be alive.” Wait a minute—no matter how quiet a day may be, dead is dead; not even the greatest silence can bring her back. But that line resonated, and though I can’t apply logic to it, it works.

Part of poetry’s magic comes from its open spaces. The reader can enter into what’s not on the page but is implied. If too much is said, if a poem is full of particular details that pertain only to the poet, then the reader is left out. If a poem is too vague, too general, then the reader can’t find the door to get inside.

During the editing process choose what to keep and what to let go of. The how of doing this develops over time. In addition to reading your new poem a few times and then putting it away for a bit, here are some pointers for editing your poems:

* Have you created an experience, a picture, or a story, for your reader?

* How does it sound? Read the poem aloud, listening not only for the authenticity of the content but for how it sounds. Do the word sounds support the meaning?

* Are all the words essential? In my draft poems I often say something, and then say it again in another way to be sure I’ve really conveyed it. Once is enough! If you’re clear, your reader will get it.

* Check your punctuation. Do each of the punctuation marks support the poem’s meaning and sound?

* How does it look on the page? Type your poem up at least three different ways by changing where you break the lines until you come to what resonates best with what you’re saying in this poem. Does the poem have stanzas? If so, remember, the stanza is to poetry what the paragraph is to prose.

58. Not by Any Other Name: Titling Your Poems

In his almost-acceptance note, the editor of a literary journal wrote to say that because I’d used the poem’s last line as its title, it was as though I’d given the punch line away before I told the joke. They would like to publish the poem in their magazine, he wrote, if I gave it a new title. The editor was right, but I was flummoxed, and there was a firm deadline. The poem had been inspired by the Fellini film La Dolce Vita. After some thought, I changed “Like Birds Taking Flight in the Italian Sky” to “Sotto, Sotto,” Italian words meaning “softly, softly.”

A poem’s title may be what gets someone to read the poem. When I pick up a collection of poetry, I’ll leaf through the book till I come to a compelling title. The poem’s title should tell a little about it, but as the magazine editor pointed out to me, it should neither give the ending away nor tell too much about what the reader will find within. A title is a little tease. It needs to add something to the poem, not duplicate what’s already there.

Some poets take the first line of their poem and also use it as the title. This can give the first line the incantatory force of repetition and is a time-honored technique. Mostly, I choose words that aren’t already in the poem. Occasionally, I’ll find words from the body of the poem that I think warrant more notice and use those for the title.

When you’re ready to title your poem, try a few on for size till you land on the word or words that, once on the page, feel like they’ve always been there.

59. Time for a Trustworthy Reader?

As a writer, you need to know that what you think is on the page is actually there and not only in your head. A reader whose opinion you can trust is invaluable. Since just after high school, my best friend Gina has been my go-to person. She’s not a poet and she doesn’t read much poetry, but she is smart, has a big heart, and knows how to listen. She may not offer technical help but when she says, “Something is off right here,” she’s usually right.

As in much of life, it’s important to ask for what you want. After you’ve chosen a reader, consider what kind of feedback you want. “Please tell me what you like about this poem” is a great place to start. If your reader can’t or won’t tell you what they like, they’re not the right reader. The person you choose needs to respect you and be willing to take direction.

Be as specific as you can when asking for feedback: “Does this line hold up? What does it tell you?” Asking questions of your reader will let them know what you’re after.

You might want to know:

* Do you get confused anywhere?

* Is my poem easy or difficult to follow?

* Anything missing?

* Does it move you?

* Is it believable? Do I sound authentic?

* How do you feel after having read it?

* I’m stuck on this part of the poem. Would you help me figure out why?

Some poems, no matter how hard we work on them, are never going to be finished. There’s a poem that I began writing on a Greek island many years ago about an elderly man and his mule. I love parts of it—but as a whole the poem doesn’t work, no matter that I’ve tried for a long time to get it right. Every now and again, I pull it out, tinker a bit, and then, frustrated, put it away. Maybe someday. Remember what we talked about earlier: writing one poem will lead you to the next one, even if that poem is a failed attempt. You need your failures as much as or more than you need your successes. That’s the way we learn. I’ll bet you’re progressing beautifully along your path.

60. Open Your Notebook and Let Your Poems Out

After you’ve been writing for a while, and are beginning to feel a sense of your identity as a poet, and your confidence is growing, you’ll likely want to take your poems to another level. Consider participating in open mics or slams at coffee shops. You might join—or start—a school poetry club. Maybe you want to begin sending your work out to be considered for publication? There are lots of online and print literary journals that welcome the work of new writers.

Poet Sara Michas-Martin says, “Try to think about publishing only after you feel true ownership of the work. When I feel I have two or three poems that make a nice group I send them out to journals that I read and admire . . . This means I read a lot of journals. I also take note of where the poets I admire publish their work and I read those journals (libraries are often the best place to discover journals devoted to publishing poetry) . . . I don’t send anything out until I’m confident the poem is fully realized and what I want to say has made it onto the page. This can take a very long time. Sometimes years.”

Before you jump into sending your work out, consider this point, also from Sara Michas-Martin: “The desire to publish can be poison to creative process. If you write only to be published you are giving someone else the power to validate your voice and attempt at creative expression. That’s not to say that putting your work out there is not important. Your voice matters, your voice should be heard.”

When you are ready, research journals to see which ones publish poems that resonate with what you’re writing. If you search for “literary journals” online, a raft of sites will come up. Be sure to check them out before sending them your poems. It can be expensive to purchase an issue from several journals. Instead, go to your local bookstore or library or ask your school’s English department, and ask other poets what journals they like and if you could borrow a copy.

When it comes to deciding where to send your poems, not only do you need to determine whether the site or publication is a good fit, but you also need to figure out if it is legit. There are many sites calling themselves “poetry contests,” and sure, they are, but they charge $25 or so to look at your poems. For better or worse, that’s a very standard reading fee for contests. I know poets who’ve spent a few hundred dollars and gotten published and others who spent similar amounts and didn’t have any luck. Look closely before sending your work.

Some contests don’t ask for any money upfront. Instead they send you a letter of congratulations, informing you that you are one of the winners and a note that “For only $50, you’ll get your poem published.” Those who fall for this do get published and months later in the mail what they receive is reminiscent of a dictionary—a hardback tome that’s stuffed with two columns’ worth of poems printed on onion-skin paper. If you read through it, you’ll see that the work wasn’t vetted; they publish whatever comes to them, by whoever will pay the fee to see their poem in print. Be cautious of any competition offering $10,000 in prize money! Here are a few to stay clear of: America Library of Poetry, International Poetry Digest, The National Amateur Poetry Competition, and Poetry Unlimited. (If you’re unsure, take a look at this site: https://winningwriters.com/the-best-free-literary-contests/contests-to-avoid/.)

To figure out which journals are legit and which are bogus, look at the names associated with the publication. Are these people whose poetry books you’ve read? If it looks fishy, chances are it is. Ask another poet or a teacher what they think. Google the name of the publication and see what comes up.

Before sending your poems out into the world to honest publishers, it’s important to be sure that your poems are ready, and that you are. When you begin to make your work public, either through a poetry performance of one kind or another or by sending poems to magazines, your skin ought to have some thickness to it.

If you send a packet of poems out and you get critiqued by an editor, remember that person is critiquing your poems, not you. Because you’re the writer, you’re going to be close to the poetry you write, and closer to some poems than others. A poem, no matter how much you love it, is something of your creation; it is not you. Repeat after me: “My poem isn’t me!” It’ll help if you can develop an attitude of hoping for acceptance but remaining prepared for rejection.

Online submission platforms like Submittable (https://www.submittable.com) and Teen Ink (https://www.teenink.com/) make sending your poems out very easy.

My suggestion is to get organized. Keep a chart of where you’ve sent your work and where you’ll try next.

61. Sound Check: Reading and Performing Your Poems

A poem can silently sing and shout from the page, but when it’s read aloud it can do much more. Your voice is an instrument—you can adjust its tone, volume and force and, in that way, bring your poems to life.

Listen and watch other poets giving voice to their work, so that you can take in the possibilities that exist in the dance between voice and breath and sound and body movement and facial expression and silence. How quiet can you make your voice? When your voice is loud, can it remain nuanced?

In addition to going to slams and readings, here are some resources for listening to poetry online:

* At the Library of Congress’s Archive of Recorded Poetry and Literature site, you can listen to poets long gone from the world read their poetry, such as Elizabeth Bishop, Robert Frost, and Audre Lorde. You can also hear recordings by many contemporary poets, such as Sandra Cisneros, Alberto Ríos, and Tracy K. Smith (who’s got a terrific podcast, called The Slowdown, in which she reads poems by other writers). (https://www.loc.gov/collections/archive-of-recorded-poetry-and-literature/about-this-collection/)

* Poets.org has many recordings, including poems by Camille T. Dungy, Yusef Komunyakaa, Rachel Eliza Griffiths, and Richard Blanco. (https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poems)

* On Poetry Out Loud’s website you’ll hear such actors as Angela Lansbury and Anthony Hopkins performing poems. Poet Kay Ryan reads Leigh Hunt’s “Jenny Kiss’d Me,” and Paul Laurence Dunbar’s “We Wear the Mask” is read by Rita Dove. (https://www.poetryoutloud.org/poems-and-performance/listen-to-poetry)

Begin by reading other people’s poems aloud. Read the same poem several times and alter your approach to it—experimenting with volume, pitch, timbre, and timing. Choosing another’s poem will be less personal than reading your own, and you’ll be able to get a more objective sense of what reading style best supports the poem’s content. Then move on to doing this with your own poems. Try standing in front of the mirror and reading to yourself.

When we read in front of others, many of us tend to clam up; nervousness constricts the voice. Nothing is better for this than breathing deeply—bring the air in with ease, not force. Thinking of your voice as coming from your belly, or, better yet, all the way up from the earth, lends the necessary strength.

Taylor Mali, who has won many national slam contests, says that biting into an apple before reciting helps him because it creates saliva, and adds that he doesn’t drink too much water so he won’t have to take a bathroom break!

Before giving a reading, consider that you’re nervous because you’re getting ready to do something important. Nerves aren’t bad if they propel us forward, but they’re a hindrance when they hold us back.

After you’ve got a few poems that you feel comfortable with, take them into the world. Will you read them from the page or memorize them? Either way, allow yourself to fully inhabit the poems and to engage with your audience—look either at their faces or right above their heads. They won’t know you’re not looking at them, but they’ll feel welcomed into your work.

62. Alternatives to Traditional Publishing

In your infinite creativity, you may want to do something entirely different from the traditional approach. Many poets are coming up with inventive ways to get their poems into the world. Here are some possibilities:

* Start a blog: Perhaps a blog on given themes where fellow poets can share their work too.

* Post poems on Twitter: A new genre of poetry exists because of Twitter’s short form.

* Make a broadside: Usually a broadside, or poetry poster, features a single poem, illustrated or not. It can be printed on heavy paper, right from your computer or at a copy shop. Some of my favorites are no bigger than a postcard. A letterpress broadside is a beautiful (and not inexpensive) thing; perhaps there’s such a printer not far from you. Or check out Etsy’s custom letterpress printing options. Poem broadsides make great gifts. You can post them on the walls of your school (if they’ll let you) or at a local café, or sell them at poetry events.

* Make your own chapbook: You don’t need a publisher for this. There are computer programs that you can use to create books, or you can go to your local copy shop and tell them what you’d like to do. I often make these and give them as gifts. Sometimes I make an illustration for the front.

* Make your own full-length book: You could crowdsource the funding to make this financially possible. Print the book through any of the online companies, or make it available online only—a less expensive way to go.

* Organize a poetry event: Get a teacher on board and host it during or at the end of a school day. Or inquire at a café in your town. Some restaurants would welcome such an event, as they’d make money from the food and drink sold to your guests.

* Create a poetry collective to publish members’ books. Everybody puts in an agreed amount of money to cover the printing costs of the first publication. When it comes out, collective members get paid back some of their investment through sales, and the rest goes to publish the next person’s title. This way, you can also help each other publicize and promote your group’s books.

Do keep in mind that if you publish these poems on a blog or on Twitter or in most any other way and then wish to submit that work to literary journals they’ll consider these poems previously published. Many journals publish only unpublished material. You might make some of your work publicly available and keep other pieces to submit to magazines.

Most importantly, this is your art form, so devise ways to share your work that fit who you are. Think outside the book.

63. Creating a Poetry Manuscript

When you have about fifteen to twenty polished poems, you may want to put together a poetry chapbook manuscript. A chapbook is a small collection of poems. The term “chapbook” comes from a time when novels were sometimes published in newspapers one chapter at a time. There are many legit competitions for these small books. Beyond that, if you have about fifty poems that are ready for the world, consider putting together a complete manuscript (again, keeping in mind that even if you self-publish, literary journals will consider the poems previously published).

Deciding how to organize a book is a lot of work, but it’s hardly drudgery. You get to look at all the poems you’ve written that you think are ready for the world and search for a through line that connects them, even obliquely. Reading lots of poetry books to see how other poets chose to order their work will be quite valuable. Some poets divide their books into thematic or chronological sections. Sometimes these sections are titled; other times, they’re numbered. The book will need a title, so you have to find what ties the work together. I had the title for my most recent book of poems, The Knot Untied, long before I had written many of its poems.

The Knot Untied is divided into five sections that all fit under its title: “An Interlacing”—poems of connection; “Tangle”—poems a bit more complicated and difficult; “My Gordian Knot”—more complication, greater sorrow; the fourth section—“The Tie That Binds”—shows the good side of being knotted together, and includes several love poems. The last section—“The Knot Untied”—brings the book’s themes together.

Another example is my anthology of poetry, Ink Knows No Borders: Poems of the Immigrant and Refugee Experience. The book is in a single section, allowing one poem to easily lead into the next. The reader can walk through the book without encountering any firm borders.

Decisions about the order of poems and whether to divide the book into sections require a lot of unrushed thinking through. Try out an order and ask a couple of knowledgeable people what they think.

When sending work to potential publishers, you’ll need to include a cover letter. (Plenty of sample letters may be found online.) Tell the editor why you want to be published in their journal and, if you’ve been published before, let them know where. If it’s a manuscript you’re submitting, the same considerations apply. You might say something about why you write and why you think they’re the perfect publisher for your work. I keep query letters simple, friendly, but to the point. Be sure all pertinent contact information is included.

Before you delve into this nuts-and-bolts chapter, take a long, cool drink of water and be sure you’re ready for something unlike what you’ve read in this book so far. This is important information but it may cause some people to flinch because it’s the antithesis of trusting your imagination and writing with enlivened surprise!

After getting a lot of publishing credits from well-respected journals under your belt, book publishers may be interested in publishing your first book. Having many poems published in highly regarded journals tells book publishers that you’re the real deal. Collections of poems don’t tend to be best sellers (unless you’re Rupi Kaur), but your publishing history means that your work has been successfully vetted and that your poems are being read, two compelling reasons for a publisher to take a risk on your book. A publisher also wants to know you’re going to work to get your new book into buyers’ hands—that you’ll give readings to promote it.

Publishing a book is costly. A publisher invests seriously in creating books—in salaries, printing, publicity, etc.—and wants to be as assured as possible that they’re not going to lose a lot of money on your book. In book publishing, as in any business, people need to make money in order to be successful, but also just to survive. And success for you, the poet, means having your book favorably reviewed and selling well. If that happens, the publisher will likely want your next book.

Usually, a contract is negotiated between the poet or their agent and the publishing house. The contract states the terms of the agreement between poet and publisher, and their respective obligations to each other.

Typically, for a paperback book, the author will receive 7.5 percent of the cover price in royalties. When a book sells on Amazon for less than the retail price (as it will), the author will receive a percentage of that price; the amount will depend on the arrangement the publisher has with Amazon. If the poet has an agent, the agent will receive 15 percent of the poet’s percentage. There may be an advance against royalties—money that gets paid to the writer upon signing the contract. That amount is based on the writer’s percentage of the minimum number of copies the publisher thinks will sell. Once the author’s percentage of the book’s earnings surpasses the amount they were paid upon signing the contract, the poet will then receive royalties from book sales. Because poetry collections tend not to sell a lot of copies, often no advance is paid. In this case, the poet should begin to receive royalties as soon as copies of the book begin to sell. Royalties are generally paid twice yearly. Even if there is no money coming to the author, they should receive a statement that shows how many books have sold.

Let’s note right here and right now that you’re probably not going to make your first million off of publishing poetry! I’m sorry to have to be the one to tell you, but maybe you knew this already so it doesn’t come as a shock.

In addition to publishing a book this way, there are poetry book publishing competitions. To enter, an applicant pays a reading fee of around $20 to $50 up front (no small change) for the publisher to consider a poetry manuscript of about fifty poems. Usually, each manuscript is read by a preliminary judge. If a couple of hundred poets submit, that raises the money to pay for a famous poet to serve as the contest’s final judge, to pay the publisher, and to cover the costs of printing the book. You can invest a lot of money and never win one of these, or you can invest a little and win. It’s a bit of a crapshoot. I tried this method a few times, enough to decide it wasn’t for me.

If your poems are strong and speak to the judges, if they’re about subjects that are in vogue and are written in a style that’s got traction at the moment, it’s less of a crapshoot, but luck is still involved.

Then there’s who you know or who someone close to you knows. If you choose to go to college and focus on poetry writing, you’ll meet professors with influence. If you know poetry people—other writers, teachers, editors—and have connections with them and if they respect your work, they may be able to assist you in getting support to publish your poetry.

66. The Poet’s Perils: Rejection

At least some of those whom you want to say yes to your poems will say no. This online journal or that magazine, this reading series or that slam, may not accept the poems you’ve given your all to—poems you may love like crazy. Rejection is as much a part of the writing process as commas and periods.

Words like “failure” or “you suck at this” or even that smallest “no” can sting. If we are labeled in ways that don’t support the authenticity of who we are, we can choose to live under those labels. Or not. Hold on to the power to define who you are, and never give it away.

Rejection will make you sad, and only those with the thickest of skins will be undeterred by it. But the thinness of your skin isn’t necessarily a bad thing. The thin-skinned among us are often the most empathic ones. Being tender will bring poems to you.

If an email appears in your inbox that says, “Thanks for the chance to consider your work!” (complete with an erroneous exclamation point) and goes on to say, “We’re sorry but it’s not what we’re looking for at this time,” it can be useful. If such notes can help you to hone your craft, that’s a good thing. However, if you allow rejection to determine and define you, it’s unlikely you’ll last long as a writer.

Learn to make a separation between your poem being rejected and your entire self being dumped. Sure, you’re deeply connected to your poems, but you are not them. Can you let the satisfaction of writing and the joy of being propelled into the next line and the next, and the feeling of having something to say, be more valuable than any negativity?

After a rejection, look over the poems to see if the editor was right, or partially right, or if, perhaps, you didn’t do your homework before sending that particular batch of poems to that particular journal. Maybe that magazine only publishes poetry about nature and you sent some poems about the workings of machines. Or maybe the editor was having a bad day.

Some poets say that anytime we get rejected, the best medicine is to send those poems out again right away. If you do this a few times, and they continue to come back to you, look again and ask a friend or a mentor for feedback. How thick is your skin now?

Very few poets in the United States, if any, make a living from publishing their poems. Poetry is a form that doesn’t sell as well as, say, romance novels or crime fiction. Most poets support themselves through other kinds of work. Some choose to work at jobs unrelated to writing and poetry, while others teach or work in publishing. For example, Dana Gioia, a recent poet laureate of California and former chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, worked for General Foods Corporation until he could support himself through his writing and writing-related work. Though the amounts vary, many poets earn money related to their poetry through speaking engagements and workshops.

A good friend of mine is one of the most dedicated poets I know; he works hard at his craft, but he makes a living as a chiropractor. Another friend, a haiku poet, gives his homemade books away and supports himself very well as a highly accomplished jeweler.

“Unlikely” has never stopped me from anything, and I don’t wish it to stop you. It’s simply important to know these realities, so that you don’t feel like a failure if, after devoting yourself to your craft for some years and even successfully publishing, you still make little money from poetry itself.

Shortly out of high school, I began teaching poetry to young people, some barely younger than I was. No school trained me to do this; I learned by teaching. I did earn a bachelor’s degree, but not till I was in my mid-twenties.

Earning money has been a pieced-together endeavor—from working in bookstores to performing one-woman shows. Mostly, I’ve paid the bills and made a life through teaching poetry in schools, community and women’s centers, homeless shelters, public libraries, colleges and universities, and for cancer survivors. As the editor of many poetry anthologies, I’ve made some money, but more importantly I’ve made books that have really mattered to me and others. Some of my books have brought me royalties. I write a monthly column for my local newspaper and publish articles occasionally. At one point, a friend and I started a small press—she invested the money and I did the work; I earned some money from the books we published. Basically, anywhere I’m invited and paid to teach, there I go. Nowadays, I earn most of my living by leading various workshops in public schools, a university, and in classes I offer privately.

My middle-class life has been made possible by my husband, who has earned more money than me every year we’ve been together. However, for the many years before he came along, I did well enough. There was always a bouquet of flowers in my living room, and I never went hungry. But I wasn’t close to being financially secure. As a self-employed person, I never know for sure what work I’ll have more than a few months (at best) in advance.

Should the path of the poet be how you wish to live, you will find your way. Determination and creativity are mighty powerful forces.

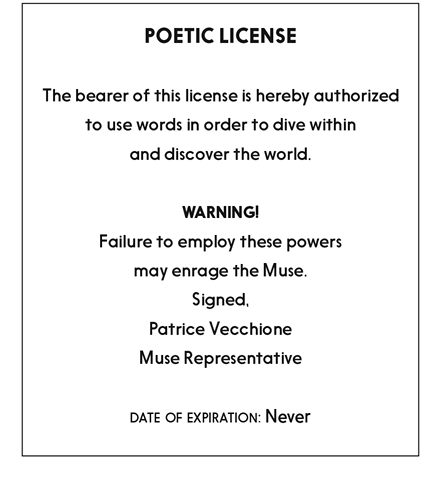

To work as a doctor, a license to practice medicine is needed. So it is for many professions. There’s a lot of schooling, likely a bunch of tests, and if you pass you receive a license indicating that you’re authorized to do that job or perform that task. To be a poet, there is no test. (Though life will test you plenty.) Nobody’s permission or blessing is needed (or, for some of us, wanted). You need only write.

But in case you ever do need it, here is your very own poetic license to copy. If you share something you’ve written and are told by an unkind person in love with the status quo, “Hey, you can’t say that!,” pull your license from your wallet, throw it down on the table, and say, “Oh, yes, I can, and here’s my license!”

69. How Writing a Poem Is Like Building a Fire

It’s early spring where I live along the Central California coast, chilly enough for early morning fires in the fireplace. I get up hours before the sun does, at an hour some call night, about 4:00 a.m. I like darkness with a promise of light.

To build a fire, you start off with old news, torn bits of paper, what others may think of as garbage—the waxed paper wrapper from yesterday’s cheese sandwich. Loosely ball this paper up and lay it down on the grate. On top of that, add twigs or small wood scraps—the smallest pieces go closest to the bottom. Then comes the striking of the match—the moment of alchemy—when the burning paper ignites the twigs in your hearth. Next come larger and larger logs. You can cook dinner over that fire or you can sidle up to it to get warm.

That’s what writing a poem is: you begin with news and scraps of experience, what others ignore—not only the wrapper from yesterday’s sandwich but snippets of conversation, memories of who you sat next to when you ate that sandwich and how warm he made you feel, the speed at which you ran laps, the feeling of your wrong answer to a question hanging in the air. You add twig words, strike the match to the page, and light it up with imagination’s fuel, creating another alchemy—your way of getting the chill out and feeding yourself creatively and spiritually.

When he was ninety years old, the cellist Pablo Casals was asked why he continued to practice. “Because I think I’m making progress,” Casals replied. Each time you write, you are making progress in your understanding of poetry and becoming more adept at your craft; over time, more depth will come to your work, as will a greater ease.

Beyond any other reason, write poems because you are engaged and curious, because you love the surprising leaps of imagination, because you have things to say, and because the act of writing poems changes you—there’s that joy again when you unfold the piece of paper with your new poem on it, read it, find yourself and part of the world in those phrases, slip it back into the pocket of your jeans, and smile because you realize nothing’s the same as it was before. The hearth’s fire is inside you now.