The Spanish poet Federico García Lorca’s poem “Romance Sonambulo” starts off “Verde que te quiero verde” (“Green, how I love you, green”). In Spanish, the verb “to want” can also mean “to love.” What words would you go so far as to declare love for?

Is it a word’s meaning or its sound that woos you? Maybe it’s the way the word feels in your mouth when you speak it. Some words are smooth. Others are ice that won’t melt. Certain words inflame me; I want to spit them out. Some words hiss; others stammer. Some tell truths we’re not able to hear.

Here are words that I love for their uplift: “stream,” “oh,” “dandelion,” “tomorrow.” “Stream” because right now it’s pouring outside the cabin where I’m staying in the near middle of nowhere, and the stream is running fast, taking with it every dubious thought I have. “Oh” is for my husband saying “Oh, baby” to me—how it sounds and what it means. “Tomorrow” is for my tendency to look ahead with glee, and “dandelion” because its yellowness says spring.

You might like to make word lists on your rainy days and pull them out when your vocabulary feels tinny to the ear. List every word you want in your life—those you crave for their meaning, their sound, how they look on the page.

Take the onomatopoeic word “perplex” that stops the tongue at the wall of “per” and again at “pl,” finally hitting hard against that last “x.” As one who is frequently perplexed, I love the word, but it’s not one I’m going to walk around with in my mouth and ears all day, as it would make me question too many things. But the wet ease and forward movement of the word “river” is calming.

At night, when I can’t sleep, I follow the technique that Patti Smith wrote about in her book Devotion (Why I Write). I’ll choose a letter of the alphabet and say all the words beginning with that letter that I can think of. Next thing I know, it’s morning.

Back when poetry first called my name, many of my poems had the word “gather” in them, in an effort to contain my un-gatherable self. Now I recoil at that word. It’s become so commonplace in advertisements for the food and restaurant world. I’d prefer to gather flowers in my backyard garden.

Begin to notice the language you’re drawn to, the words you respond to upon hearing or reading them, those that repeat in your poems, and the ones you want to invite into your writing. The novelist Hortense Calisher said, “The words! I collected them in all shapes and sizes and hung them like bangles in my mind.” Yes, do that.

The simplest (and my favorite) definition of a poem is “a picture made out of words.” It’s a picture of an instant in time, a memory, the sketch of a person, animal, or place, a true or invented occurrence, the moment of change.

Through the use of images—things that can be seen, smelled, tasted, touched, or heard—poets turn thoughts and feelings into poems. Those word pictures may show us what we don’t expect to see and may take us to places we might otherwise never visit.

A poem can’t recreate an experience—that’s already come and gone. Rather, a poem becomes a new thing. The event is what made you reach for pen and paper or phone.

First there’s what happened, either something in “real” life or in your imagination, your heart.

Writing your poem is the second thing. Through the process of writing, that magical, unpredictable experience of alchemy, the bare bones of what occurred and what you were feeling about it shifts and deepens. You may discover that it’s connected to other experiences, and those may enter the poem also.

The third thing is the poem itself. Instead of being a retelling of what happened, it will be its own thing, your own thing, comprising who you are and who you were and, maybe, who you will be.

There is no subject that a poem can’t touch. Nothing is too small or large or unimportant. Remember this: what comes to you is what is there for you to write. In poetry, there’s never one right answer, never only one way to describe anything—from a slap across the face to the view from a mountaintop.

Most poems contain a rather small collection of words—images, phrases, sentences. You can hold a poem under your tongue or slip one into your pocket. Short on words, however, doesn’t imply light on meaning. In a poem, every word carries weight.

A poem can express the inexpressible. A ten-line poem may boomerang in your heart for days. It may change how you see yourself or how you understand the world. Take this one by Rumi, the Persian poet born over eight hundred years ago in what is now Afghanistan:

We are walking through a garden.

I turn away for a minute.

You’re doing it again.

You have my face here, but you look at flowers!

Feel the poet’s grief? It only takes Rumi two lines to set the scene and only two more to make us sad. You know what it’s like to be ignored, don’t you? Poetry gets to the essential, and quickly!

The nineteenth-century American poet Emily Dickinson said, “I hesitate which word to take, as I can take but few and each must be the chiefest.” Because a poem is made of condensed language, each word counts. Which are your “chiefest” words?

However, as true as Dickinson’s statement is, in the first drafts welcome every word that comes. Don’t pick over them like fruit in a basket. Later, in final drafts, you’ll need to decide which words are the best ones and keep only those, but at first accept them all.

Poetry relies on concrete language, not abstraction. If Rumi had written, “She doesn’t love me anymore,” you might not believe him. The poet shows us what he feels through describing the actual world.

Poems recognize life’s small gestures and draw readers to notice things that, if the poem hadn’t been written, likely would have gone unremarked upon—the delicate drift of a downward falling leaf, a face searching for yours across a crowded room—and show them to us in new ways.

The English poet Eleanor Farjeon, born in 1881, wrote:

The tide in the river runs deep.

I saw a shiver

Pass over the river

As the tide turned in its sleep.

Until reading her poem, I’d have never thought of a river sleeping. And can’t you picture that “shiver” as the tide changed?

Farjeon’s poem leaves a lot out. She doesn’t tell us what trees grow alongside the water. Nor does she indicate who is observing the scene. Poems never say everything; they always leave something out. A poem’s job is not to tell you how to get to the corner of Sunset Avenue and Fourteenth Street. The poem wants to give you a sense of standing at that windy corner. By leaving parts of the story out, the poem invites the reader in.

If a poem were a simple mathematical equation, it wouldn’t be 1 + 1 = 2; it would be butterfly + mountain = the first moment I saw you. A poem often takes leaps like Superman, “able to leap tall buildings in a single bound.” Not everything is explained but somehow the poem isn’t missing anything. That is its integrity.

A poem can allow the speechless to speak. In her poem “to the sea,” Aracelis Girmay writes:

How dare I move into the dark space of your body

carrying my dreams, without an invitation . . .

The ocean can’t literally invite her into its water, but Girmay imagines it could. That’s one way a poem enlarges our understanding of the world, by making it possible for us to see differently.

Sound is an important and unique element to poetry. But for now, keep in mind that, though not all poems rhyme, the element of sound is nearly always at work. Sometimes it’s quite obvious, like the beat of a drum, while in other poems, it’s subtle as the beat of your heart at rest.

Both when writing and when reading a poem, though your body may be still, you begin in one place and end up in another.

24. The Various Forms Poetry Takes: From Free Verse to the Villanelle

Most poetry that’s published these days is written in what’s called “free verse.” These poems don’t follow a formal form. Without rhyme or repetitive meter, the direction the poem takes isn’t controlled by a predetermined pattern. Often poets create their own structures for their poems—a particular poem might be written in couplets, or the poet may repeat a single phrase for emphasis.

Sometimes “free verse” gets confused with “blank verse,” which is not at all the same. Blank verse is unrhymed poetry written in iambic pentameter, the most traditional meter, with lines of ten syllables each, in which an unstressed syllable is followed by a stressed one. Iambic pentameter rhythm is akin to the da-dum of the heart, making it not only predictable but familiar and comforting. Here are two examples (the stressed syllables are in bold): From Twelfth Night, by Shakespeare, “If music be the food of love, play on”; and from John Donne’s “Holy Sonnet XIV,” “Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new.”

There are many types of poetry. You’re likely familiar with haiku, a form originating in Japan that has only three lines (five syllables in the first and third line and seven in the second). I’ll bet you wrote at least one haiku at some point in school. Other forms may be new to you. The ode is a poem written in dedication to someone or something. An elegy is a poem written upon a loved one’s death in which the beloved is remembered and celebrated. Perhaps you’re familiar with the sonnet, a fourteen-line love poem that originated in thirteenth-century Italy. Two highly structured forms that are popular these days are the sestina and the villanelle. In the third section of the book, we’ll look at the ghazal, a very old form that comes from seventh-century Arabia.

Striving to fit into a precise form is actually expansive; you’ll write in ways you wouldn’t naturally be inclined to.

“Poems are a form of music, and language just happens to be our instrument—language and breath,” says the poet Terrance Hayes. Whether it rhymes or not, sound is more intrinsic to poetry than it is to any other written form, except for songs.

Remember learning the ABC song when you were little? When rhythm and/or rhyme is added to what’s said, it makes the information easier to remember.

Meaning doesn’t just come through a word’s definition but through the sounds the word makes. Take the sound of the word “please,” how it eases into the ear, asking.

To give a sense of how sound works, let’s look at excerpts from two very different poems. “Speech to the Young: Speech to the Progress-Toward,” was written by Gwendolyn Brooks, an American poet born in 1917, who began publishing her work when she was only thirteen years old. The poem begins:

Say to them,

say to the down-keepers,

the sun-slappers,

the self-soilers,

the harmony-hushers

This punctuative, declarative poem is like a chant. Brooks’s staccato keeps the poem moving at a brisk clip.

“Rock Me to Sleep,” by poet Elizabeth Akers Allen, was written in the 1880s. It relies on end rhymes, as was typical of poetry then:

Backward, turn backward, O Time, in your flight,

Make me a child again just for tonight!

Mother, come back from the echoless shore,

Take me again to your heart as of yore

With its rhythm, made up in part of the vowel sounds—the repeated “o” sound, and the pleading of the long “i”—this poem conveys a sense of longing.

Years ago, at a retreat center by the Pacific Ocean in Washington, I participated in a weeklong writing workshop led by Mary Oliver. What stuck with me most was what she taught us about the element of sound in poetry.

“Say the word ‘rock,’” she instructed, “and then say ‘stone.’” “Rock” sounds rigid. We know “stone” to be a hard thing, but with the softness of the “s,” the openness of the “o” and “n,” the word itself conveys softness.

Oliver went on to list word ending sounds that stop readers, at least as much as punctuation will, and those that effortlessly lead a reader into what comes next. Only a few ending sounds halt us in our tracks. “B,” “d,” “g,” “k,” “p,” “r,” and “t” will cause the reader to stop abruptly. This is true whether we’re reading to ourselves or aloud.

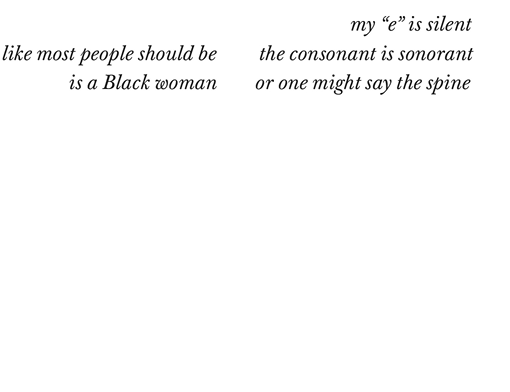

Look at these three lines from the poem “etymology,” about her first name, by Airea D. Matthews:

The last word of the first line—“silent”—stops us, doesn’t pull us into the next line quickly, so that when we get to “like most people should be” we’ve had a moment to get ready. Again, in the next line, the abruptness of “t” slows our reading. The following line, though, ends softly, with the word “spine” pulling us along.

Ultimately, everything about a poem—line length, sound, punctuation, tone, and syntax—supports its meaning. And the unique way in which each poet puts these things together makes up a writer’s style.

Here are a few brief definitions of aspects of sound in poetry that you might want to experiment with:

RHYME, HALF RHYME, AND INTERNAL RHYME

* Rhyme is when the ending sound repeats. From William Blake’s “The Tyger”:

Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night

And from Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “Sonnet,” which she wrote when she was just seventeen:

With melody, deep, clear, and liquid-slow.

Oh, for the healing swaying, old and low

* Half rhyme is when the ending sound almost rhymes, but not quite. Some years back, the musician Eminem was able to rhyme the word “orange” with “door hinge” and “four-inch,” partly because of how he accented the words.

In Yeats’s poem “Lines Written in Dejection,” he says,

When have I last looked on

The round green eyes and the long wavering bodies

Of the dark leopards of the moon?

* Internal rhyme is when a word within a line rhymes with a word within or at the end of another line. Many poems with internal rhyme also use ending rhyme. From Edgar Allan Poe’s “Annabel Lee”:

For the moon never beams, without bringing me dreams

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And the stars never rise but I feel the bright eyes

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee

Rhyme, rhythm, and meter help us to learn poems by heart and contribute to the music of a poem.

RHYTHM AND METER

The various kinds of meter hold in common a pattern of sound—the repetition of particular groups of syllables. Some syllables are stressed while others are quiet.

In iambic pentameter, the most common meter, which resembles the sound pattern of the heartbeat, the first syllable is unaccented and the second is accented. “Come live with me and be my love,” wrote Christopher Marlowe. And from Shakespeare: “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?”

Read these lines aloud and notice the subtlety of sound, how your voice moves from down to up. Because your voice is quieter in the first syllable, the accented second sound is reinforced.

Whether or not you choose to rhyme your poems, or to write in formal meter, tuning your ears to how sound works in poetry will make your poems stronger.

You with your beautiful body and the world of human beings with theirs are hardly the only ones for whom shape matters. Expand the definition of “being” to include poems, and note how poems can also be wide or narrow, angular or rounded.

Most poems appear as lines on the page. The length of a line contributes to the meaning of that line, and to the meaning of the entire poem. This is unique to poetry—prose doesn’t offer readers sculptural shape. In poetry, the place where the line ends is called the “line break.”

Read a particularly angular poem that’s got only one or two words on each line and you’ll notice there’s a lot of white space on either side of the poem, so whatever appears on the line, whether it’s as insignificant as “the” or as striking as “fire,” is going to get a lot of attention standing all alone in the middle of the page. Consider this when deciding how to shape your poems—does any single word in the poem require that kind of priority? This is usually decided in the later drafts of a poem, because we’ve got to be well inside the poem in order to know.

Let’s look at one sentence, near the middle of Jenny Xie’s poem “Naturalization”:

The years are slow to pass, heavy footed.

What if she’d broken it this way:

The years are slow

to pass, heavy

footed.

We wouldn’t know what about the years is slow till we got to the next line, nor would we know in what way they were heavy, which would create a very different effect. By giving us the sentence in a single line, Xie tells us that she wants to convey this material all at once, not bit by bit.

No matter how many words appear on a line, the two words that will receive the most attention are the line’s first word and, especially, its last. A line’s final word is what a reader is left with, even for the fraction of a second it takes for the eye and mind to travel to the beginning of the next line.

The most traditional approach is for a line to contain a single phrase or sentence, giving a reader enough content to be momentarily satisfied. If a poet wants to pull a reader quickly through their poem they may end a line in the middle of a thought with a word that ends softly. If a poet wants to unsteady a reader, they may end a line in an entirely unexpected place, almost defying the line itself, and in those cases, they may choose words that have hard ending sounds, to create a jarring effect. Let’s look at a few examples.

Robert Louis Stevenson begins “Bed in Summer” this way:

In winter I get up at night

And dress by yellow candle-light.

The first line ends with certainty. Stevenson has given us a phrase, enough to satisfy, ending the line with a hard-sounding word. The next line completes the sentence. (Note that the second line, which is not a new sentence, begins with a capitalized word. This is old-school. Plenty of contemporary poets do it too. It’s a personal choice. As I see it, a line beginning with a capital letter that doesn’t begin a sentence keeps me from moving easily into the next phrase. In my own work, I only capitalize the first word of a line if it also begins a new sentence.)

In the opening to Margarita Engle’s “Turtle Came to See Me,” she both ends lines at the conclusion of phrases and breaks this pattern:

The first story I ever write

is a bright crayon picture

of a dancing tree, the branches

tossed by island wind.

The first two lines give us almost enough content to be satisfied, but not quite; Engle is pulling us into her poem. That third line, though, because there’s no verb in it, makes us wonder about the branches. She’s urging us onward.

Here’s “A Strange Beautiful Woman” by Marilyn Nelson:

A strange beautiful woman

met me in the mirror

the other night,

Hey,

I said,

What you doing here?

She asked me

the same thing.

Take a look at the fourth and fifth lines. Nelson wants to slow us down, to get us to pay attention. In most poems, the words “I said” wouldn’t warrant standing alone on a single line because those words are generally only segues to further content, but here Nelson is using the words as a single line to let us know something’s going on that we should take notice of.

In addition to how an individual line conveys content, there is what the stanza does. A stanza—a unit of lines—is akin to a paragraph in prose. Stanzas signify a separation, a transition, letting the reader know that something a bit different is happening. It could be that each stanza offers a particular point of view. Two-line stanzas are called couplets, three-line stanzas are tercets, and four-line stanzas are quatrains.

The best way to get familiar with how to use line and stanza breaks is to experiment. Take a line in a poem you’re working on and break it in multiple ways, and notice how you influence the meaning by doing so. Do this with stanzas also. Or take someone else’s poem—maybe a favorite published poem—and see what happens when you break the lines differently from the way the poet did. I’ll bet by doing so you’ll discover why the poet did what she did. And, of course, as with all aspects of acquainting yourself with poetry, read, read, read, and see how lots of other poets handle lines and stanzas.

27. To Punctuate or Not to Punctuate

Another thing I learned from Mary Oliver that has stayed with me comes from the one-on-one session we had. She’d read a handful of my poems and, noticing my inconsistent use of punctuation, suggested that I pick—either punctuate a poem correctly and completely, or don’t use any punctuation at all. In a kind way, Oliver was pointing out that my inconsistent use of punctuation reflected a lack of clarity of thought, and she was right.

Poets each find their own way to this, and the way punctuation is used may depend on the poem. In some of his work, W. S. Merwin used neither punctuation nor capital letters, and his line breaks appear design influenced—those poems look block-like on the page—rather than content determined. He punctuated other poems in a customary way.

Here’s the opening of his poem “Rain Light.” Though Merwin uses no punctuation and his only capital letter is the one that starts the poem off, as you begin to read, it’s clear that nearly each line is a sentence:

All day the stars watch from long ago

my mother said I am going now

when you are alone you will be all right

whether or not you know you will know

In some of his work, though, it’s not at all obvious where one sentence ends and the next begins. A few readings are needed to figure out where a new thought starts. Take the opening to “End of a Day”:

In the long evening of April through the cool light

Bayle’s two sheep dogs sail down the lane like magpies

for the flock a moment before he appears near the oaks

a stub of a man rolling as he approaches

smiling and smiling and his dogs are afraid of him

Consider punctuation, like line and stanza breaks, as directions you provide to guide the reader, indicating, “Slow down a little here” (with a comma); “Stay a bit longer here” (with a period); “Let’s hang out for a moment” (with a stanza break). The reader wants to know he can trust you, so tell him what you want him to do. Or you can, like Merwin, make a reader work to find their way, allowing not only for potential confusion but for discovery.

The elements of voice and style are very closely connected and, like cracks in the sidewalk, they’ve always tripped me up. If they baffle you, too, don’t feel bad. Defined simply, style equals diction (word choice), and tone. Both convey the writer’s attitude toward their subject. Each writer has their own voice; it’s what makes the writing uniquely theirs. Now for a closer look.

Here are the opening two lines of two very different poems that begin in almost the same way. First is “Daughter,” by Jon Pineda:

Let us take the river

path near Fall Hill.

Next is “OK Let’s Go,” by Maureen N. McLane:

Let’s go to Dawn School

and learn again to begin

Though small, the difference between “Let us” and “Let’s” is distinctive—“Let us” is formal, whereas “Let’s” is relaxed. It’s style that allows Pineda and McLane to each convey their own sensibility and tone. And then there’s the informal tone of McLane’s “OK.”

Some poets write in an ornate style. Others have a straightforward approach. Some build a poem from simple, single-phrase sentences; while others write entire poems consisting of one long, complex, twisting and turning sentence. The way a poet designs their poems on the page—their actual appearance—also contributes to their style. Attitude toward a subject is conveyed through both word choice and tone. Respect or disrespect toward a subject will determine a writer’s word choices. The style of a particular piece of writing is also determined, in later drafts, by consideration of the intended audience.

A poet’s voice is the written manifestation of their personality. How you will say things is unique to who you are. Through writing (and writing), poets refine and expand their unique way of expressing themselves. In his book The Art of Voice, Tony Hoagland says, “The role of voice in poetry is to deliver the paradoxical facts of life with warmth and élan, humor, intelligence, and wildness.”

Our poetry voices are based on the voices we’ve heard during our lives, as well as how language is used in the places we’ve come from—including sounds other than human voices, such as city background sounds or those of the ocean. Were you read to as a child? Did someone tell you stories? Those will influence your poet’s voice too. My mother read me poetry every day from the time I was a baby, and though my poems are nothing like A. A. Milne’s children’s poems, the rhythm of his work is present in my own.

Tony Hoagland said, “Whatever the ‘matter’ of a poem is, it is carried along on the fluid tide of a voice.” It is not only poets’ different content that makes their work identifiable to you, but the way their voices handle that content—a kind of signature, as unique to them as their dreams and fingerprints. The way they write about their content is their voice.

Both Frank O’Hara’s poetry voice and style are conversational. He wrote in a way that conveys a friendliness and accessibility. When I read O’Hara’s poems it’s as though he’s in the room talking to me. Take the opening lines, the first stanza, to his poem “Animals”:

Have you forgotten what we were like then

when we were still first rate

and the day came fat with an apple in its mouth

“Have you forgotten” implies we once shared something together, and even though we’re his readers and not his friends, his language brings us in. O’Hara’s tone and attitude come through in his anticipation, as though he were preparing for the feast of his life. Style and voice are interwoven and worth looking at closely because understanding them will help you as you discover the way in which you’ll write your poems.

29. “Since Feeling Is First”: The Troublesome Adjective and Getting to Original Thought

E. E. Cummings wrote a poem called “Since feeling is first,” and as the author of nearly three thousand poems, he ought to know. The poem begins this way:

since feeling is first

who pays attention

to the syntax of things

will never wholly kiss you;

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

and kisses are a better fate

than wisdom

Feeling is often first; it’s poetry’s turf. Much creative writing begins out of a shift in feeling—unsettled or suddenly elated, we reach for a scrap of paper.

Typically, when asked, “How are you?” we respond by saying, “Fine.” But what is fine? All that response will commit to is being positive, and it’s not necessarily honest (but convenient, yes). Saying “fine” may also be a way to avoid saying what’s true, if you don’t want to reveal that, at the moment, you’re falling apart.

What if, when asked, “How are you?” you answered, “A little blue around the edges but sugary once you get deeper in,” or “Spicy. Today, I’m enough to burn your tongue!”

The limitedness of “fine” doesn’t belong to that word alone. Other abstract adjectives such as “nice,” “pretty,” and “wonderful” aren’t actually nice, pretty, or wonderful. They’re vague and, in poetry, leave too much up to the interpretation of a reader. When a poem requires a reader to read it a few times, it should be to understand the poem’s complexity, not to try to decipher its meaning because the poet hasn’t done his job. The use of abstract adjectives conveys a lack of conviction, indicating that the poet is unsure of what he’s saying, and that means that the poem isn’t finished.

By the time you get to a final draft, you need to convey an integrity of meaning in your poem. The poem needs to show why you think and feel as you do. Are you enamored of a guy because of how well he listens when you share something important? Is he calm when you get ruffled, patient when you’re ill-tempered?

I could tell you that my friend is nice because (sometimes) she is, or I could tell you that the winter sunrise this morning was nice because it was. My friend, however, doesn’t turn pink and orange and come up at morning, and the sunrise doesn’t laugh the way that girl does. Ntozake Shange, most famously the author of the choreopoem for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf, said, “A poem should happen to you like cold water or a kiss.” Feel how physical and unequivocal, how not abstract, that is.

Consider these lines by the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, from his love poem “Sonnet Eleven.” When Neruda writes, “the liquid measure of your steps,” can’t you see the smooth ease of movement? And when he says, “I hunger for your sleek laugh,” have you ever thought of a laugh as being sleek? I hadn’t. In describing his love, Neruda says, “the sovereign nose of your arrogant face,” making the reader see a proud rather than boastful woman.

When using adjectives, choose sensory ones that you can see, hear, smell, touch, or taste—ones that live in the body. Embrace words like “tall,” “jagged,” “ripe,” “bitter,” “acrid,” “toothsome,” “creamy,” “blurred,” “prickly,” “solid,” “smooth,” “elastic,” “rough.” If you’re going to use adjectives—and you will—make them unpredictable and as specific as possible.

There is one caveat when it comes to the abstract adjective: in life, if someone you love says, “Hello, gorgeous,” that’s a good thing. Maybe don’t ask that person to be more specific.

Poets use similes and metaphors to express their point of view and to give clarity and depth to an image, experience, emotion, or idea. Both techniques compare two dissimilar things by showing readers often-surprising ways in which they’re alike.

Léopold Senghor was both a poet and the first president of Senegal. In his poem “I Want to Say Her Name” he personified features of Africa that he loved, writing:

Naëtt, her name has the sugared whiteness of coffee trees

in flower

It’s the savannah which blazes . . .

Naëtt, it’s the dry whirlwind and the dense clap of

thunder.

In “Poems for Blok,” the twentieth-century Russian poet Maria Tsvetaeva wrote a poem to her poet friend Alexander Blok:

Your name is a—bird in my hand

a piece of ice on my tongue . . .

A ball caught in flight,

a silver bell in my mouth . . .

How much there can be in a name! We know that a name doesn’t literally have sugared whiteness, nor can a name be a silver bell. But, by making these leaps, both poets articulate their feelings—Senghor for his continent and Tsvetaeva for her friend.

Similes, as you likely learned in grade school, most often use the words “like” or “as” (or, less commonly, “than” or “as if”) to bridge the two parts of the sentence. The metaphor does away entirely with the bridge and takes a leap, saying this is that.

This poem fragment by the ancient Greek poet Sappho is made up of only a single simile. By showing us wind through a tree, Sappho demonstrates what’s happened to her heart:

Without warning,

as a whirlwind

swoops on an oak

love shakes my heart.

Having been awakened from a nap on a hot day by the sound of someone walking into his room wearing tinkling ankle bracelets, Michael Ondaatje wrote an ironically titled poem, “Sweet Like a Crow.” It begins:

Your voice sounds like a scorpion being pushed

through a glass tube

like someone has just trod on a peacock

like wind howling in a coconut

like a rusty bible . . .

Next time you or I are woken from a nap, may it have poetic consequences!

In her poem “Dear America,” Rachel Eliza Griffiths uses both metaphor and simile in a single sentence:

Your alphabet wraps itself

like a tourniquet

around my tongue.

An alphabet can’t literally wrap itself around something, nor is it actually a tourniquet that cuts off circulation, but Griffiths wants to demonstrate the power that one particular alphabet has over her.

In his poem “Love in the Ruins,” Jim Moore uses the words “as if” to connect something common with something of great importance, describing his mother

folding the tablecloth after dinner

so carefully,

as if it were the flag

of a country that no longer existed,

but once had ruled the world.

That’s some folding. Feel the care she gives her task, leaving the reader with a weight of sadness?

Experiment with this: spend a day writing similes and metaphors unconnected to poems. Make a bank of them—some that, at first glance, are wild and unconnected—to draw from later. Including figurative language is another way to draw your readers in.

Along with reading and writing poems—and living life, and staying aware of what’s around you so that you can respond—memorizing poems will support your writing greatly. Once you no longer need to look at the words on the page, you’ll be able to fully enter and get to know a poem. And that will allow you to hear and feel what it most intimately says.

To say a poem out loud gives the words far greater power than when they rest silently on paper. Memorize a poem and make it yours, and you can stand beside any of your favorite poets, from Elizabeth Acevedo to Emily Dickinson. With a few poems under your belt, you’ll never be bored or lonely again! Those poems will keep you company when you’re waiting in line for coffee. You’ll be a great asset to any party—if the conversation lags, recite a couple of poems and the room will become lively again as listeners respond.

We talk of this as “learning by heart,” but one evening, after reciting several poems to my friend Cheryl’s grandkids, her grandson Sami asked, “Do you know any more poems by head?” Luckily, I did. We use our heads to fasten the poems securely to our hearts.

Here are some suggestions for learning poems by heart (and by head):

* Only memorize a poem you love.

* Begin with a short poem.

* Silently read the poem over a few times, getting to know it.

* Next read it aloud a few times and begin to lift your eyes from the page. Memorize the poem phrase by phrase, then sentence by sentence.

* Notice clues within the poem that will aid your memory, such as end rhymes or content or sound repetition—perhaps an “m” sound that you hear over and over. Use the content to help you remember. If something in the poem reminds you of an experience you’ve had, that will make memorizing it easier.

In the final section of this book we’ll talk about reading poems aloud and performing them. This is a good place to start.

The best room of my own was the third-floor San Francisco studio at the corner of Larkin and Union where I lived by myself for a year when I was in my early twenties. In a corner of the room, atop my father’s drawing table, in front of the three big windows, sat my electric Smith Corona typewriter. It was the first thing I saw upon waking each morning.

Now my office is a bedroom in our small two-bedroom house on a nondescript, quiet street in Monterey. I love this room not so much for the window that looks out at a Monterey pine tree, but because when I’m there, the cats, Ace and Stella, usually join me, and any place is made better by their whiskered presence. (The poet William S. Burroughs said, “My relationship with my cats has saved me from a deadly, pervasive ignorance,” and I concur.)

In my office there’s a long narrow desk that my husband built for me, and more books than bookshelves; the un-shelved books form disordered columns on the floor. It’s been said, “Creative minds are rarely tidy,” and I agree—neither my mind nor my room could be described as tidy. The desk is often covered with piles of papers. I think the external chaos is a manifestation of the chaos in my head, and that’s oddly calming.

In addition to the cats, I keep certain objects around me that hold meaning. There’s a large yellow and red Guatemalan painted box that serves as an altar to creativity. Atop it sits a photo of the fox who once spent a weekend in my backyard, a photo of my mother before she was wrung out, a rough garnet crystal that I found in a nearby wood, and a note from a former second-grade student, which reads, “Pictures just come to my mind, and I tell my heart to go ahead.”

Novelist Rachel Kushner says, “I know that things bear mystical emanations. . . . I’m particular about what things are allowed in. Only those that glow with some kind of special meaning.” It comforts me to know that other writers also surround themselves with objects that function as talismans to support their writing.

If you don’t have a room of your own in which to work, where will you write? Poet Paul Muldoon says, “I’ve now made a virtue of necessity and am committed to the idea of the workspace as pop-up.” He writes at the dining room table, “which I now reconfigure each day in the hope of doing a little divining.” Divining—now that’s a great word to describe what poets do. At day’s end, the poet clears the table so the evening meal may be enjoyed there.

Safia Elhillo tells me, “I spend most of my life traveling . . . so I don’t have a favorite location to write, though I would love to have one someday—a favorite café or a real desk. . . . Mostly I write in bed, wherever I am. And I like writing on the Amtrak, too—the tray tables are almost the perfect height.” Kim Addonizio says, “Mostly I write on the couch or in bed, where I feel far away from the world and things.”

If you have your own bedroom, you might turn a corner of it into your writing space and adorn it with items of significance. If you don’t have a room that’s yours, like Paul Muldoon, create pop-up workstations, or write in bed or in the stacks at your local library. You might bring a small object that glows with you, or perhaps your dog will curl up at your feet.

Though a lot of you is required to write a poem, not a lot of materials are needed. Writing is a portable art form—stuff a notebook and a pencil in your backpack, or pull out your tablet, and you’re good to go.

When working on a screen, keep your drafts so that you can go back to them. I often reclaim parts of early versions. You might find the perfect word or phrase there.

I’ve found that the tools I use can influence what I write. When writing poems, I tend to begin with pen and paper and to write the first couple of drafts by hand. The physical sensation of holding the pen and moving it across the paper: the nub of it, paper absorbing ink, the fluidity of my horrible handwriting, smooth and slow, except when a thought comes quickly and my pen scrambles to catch it all. After that, I’m back to slow—a pace I’m rather fond of and don’t have enough of in most parts of my life. Once I’ve got a solid paper draft, I reread it and go to the computer, where, as I type the material, it begins to take final form.

Writing prose tends to begin, for me, at the computer. Because of its greater linearity and the speed at which my initial thoughts tend to come, having the keyboard beneath my fingers works best. But to begin a poem that way would be a bit like broadcasting news before the story’s happened.

When I was in middle school, my mother insisted I learn the keyboard. If all else failed, she was determined that I’d have typing as a skill to fall back on. It’s one that helped keep her employed as a secretary throughout her working life. She could type something like 183 words per minute with maybe only a couple of mistakes. A few hours every day of one terribly long summer were spent before my mother’s IBM Selectric typewriter. I wasn’t a happy girl; my friends were at the beach while I was stuck indoors stumbling before a humming machine. I can’t type 183 words per minute, but thanks to her, I’m pretty fast!

The notebook—we’ve got to talk about the notebook. You need one (or several). It doesn’t matter what kind. I personalize mine, often with a collage on the front. On the inside covers I write quotes that I find encouraging so that when I’m on the verge of frustration, I read one and am revived.

When I asked the poet Sara Michas-Martin for her suggestions to new writers, she responded, “Keep a notebook with you. Draw in it. Write down things people say, lines from books that grab your attention, and observations about the world.”

I also keep what I call Another Notebook nearby, to jot down ideas that don’t immediately fit in with what I’m writing but that I want to keep for possible later use.

34. Rules You’ll Love to Follow: A Surprising List

These may be the best rules you’re ever given, though it’s likely they won’t be the easiest to follow. Initially, I made this list, bit by bit, for myself, and I have scoffed at it upon occasion; but I keep coming back because it works.

#1. What you write doesn’t have to make sense. Let yourself be foolish.

“What you write doesn’t have to make sense” is not to suggest that you write a random collection of words as though they’d fallen out of your pocket, and there you are scooping them up from the sidewalk before the wind takes them. But it’s also not to suggest that you don’t do that. Sense will come; there’s no need to hurry to get there.

#2. Trust your imagination. Creative writing goes beyond mere intellect; trust your imaginative abilities.

#3. Don’t plan what you’re going to say. Let yourself be surprised by what you write.

When it comes to your plan for writing, hold the reins to your ideas loosely. If you write without having a firm control over where you’re going, you may end up in some pretty cool places.

Listen with an attentive ear, an open heart, and a trusting mind. The more you do, the more words will come. And don’t try too hard.

#4. Spelling, punctuation, grammar, and neatness do not matter in a first (or second) draft.

Perhaps you are a good speller, or maybe not. If you’re writing in a notebook and you misspell a word, it doesn’t matter.

The more I write, the worse my handwriting becomes. The point of this rule is to differentiate between the essence of your writing, its content, and the outward form. Address spelling, punctuation, and grammar after your initial drafts.

#5. There is no wrong way to write your poem: “Protect your vision.”

Joni Mitchell says, “I believe a total unwillingness to cooperate is what is necessary to be an artist—not for perverse reasons, but to protect your vision.” The artist is the one who sees another path, who wants to forge a path for herself (not necessarily for anyone else to follow) because the well-worn route doesn’t go in the direction she wants go.