The Problem

Sigh out a lamentable tale of things,

Done long ago, and ill done.

—JOHN FORD, The Lover’s Melancholy

MY SEARCH for Amedeo Modigliani began a few years ago in the East Wing of the National Gallery of Art in Washington. I had always known about this Italian artist, who lived in Paris at the same moment as Romaine Brooks did, an American expatriate with a similar passion for portraiture, about whom I wrote. Both took singular paths but moved in different circles, to put it mildly. There were other differences. Whereas Romaine Brooks’s success in 1910 was immediate—Robert de Montesquiou called her “A Thief of Souls”—Modigliani’s achievements took decades to be appreciated. Whereas Romaine Brooks is a minor art historical footnote nowadays, Modigliani’s reputation continues to soar, to judge from the prices paid for his paintings. Romaine’s work, with its monochromatic palette, came, as Hilton Kramer wrote, at the end of the Whistler inheritance; Modigliani’s was outside every movement. Yet one could perceive a searching intelligence at work in both, infusing their images with the same rigorous intensity. I was slowly becoming as interested in him as I had been in her. Then I found his art.

In contrast to the neoclassical National Gallery created by John Russell Pope, with its elegant detailing and hushed, inviting galleries, the East Wing’s rigorous spaces of pink granite, steel, and stone, and its chasms of glass, inhibit, rather than welcome, an aesthetic response. Machines for living are one thing, habitations of the spirit another, and so I wandered one day by accident into one of its rooms off the main concourse. There I came upon eight Modigliani paintings and one sculpture, tucked away unobtrusively in a diamond-shaped room. The matte-finish walls in a grayed-off cream, the ceiling spotlights, and the industrial-weight carpeting had the negative virtue, at least, of not competing with the presence of these hidden jewels.

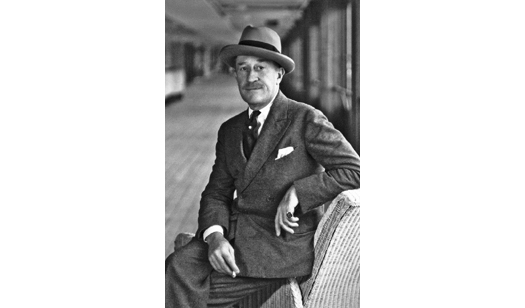

The collection had been assembled by Chester Dale, who, like many other great collectors, was a genius at financial prestidigitation, was small, large-featured, and plain. Having a sense of style, he compensated for this handicap with flamboyant hats, heavy and expensive rings, and an indefatigable willingness to offer himself as a model to such artists as George Bellows and Diego Rivera. Perhaps the most telling portrait that resulted was by Salvador Dalí, who depicted the collector looking out complacently from the frame, bearing a solemn and unmistakable resemblance to his poodle. By then Dale was acquiring paintings as relentlessly as he had once pursued stock options, thanks to his first wife, Maud. She nagged and prodded her husband to buy Modiglianis by the dozen at a moment, in the early 1920s, when they could almost be had in job lots.

Chester Dale, c. 1930 (image credit 1.1)

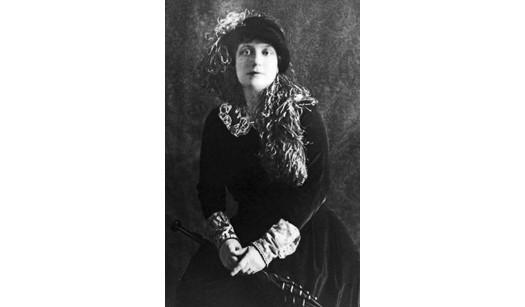

Maud Dale, 1927 (image credit 1.2)

The Modigliani room was being patrolled by a taut-looking, gum-chewing guard with a Fu Manchu moustache and a wary expression. When asked how much he liked being in that room, he said, “I don’t.” A few people were wandering through, a couple speaking Russian and a short Japanese man in glasses and a black shirt. I stopped first beside Modigliani’s portrait of Monsieur Deleu, painted in 1916, which I had seen in reproduction but which I could almost say I had never seen, since the work itself was so startlingly different. Instead of what looked, from picture books, to be an uninteresting study of a heavyset, black-haired man with a pursed mouth in flat planes of gray, black, and russet, this was a revelation.

The expression, at first glance a caricature, was in fact full of dexterously applied details, such as a touch of light in the left eye, a shadow under an eyebrow, and the play of volumes around the mouth and chin. What had seemed superficial was in fact full of nuance. Was he frowning slightly, or mulling a point, or drawing back from life itself?

The sense of enigmatic intent extended to the dappled light and shade on the sitter’s jacket and the close attention given to what is usually least considered, i.e., the background. Each stroke of the brush seemed to have been placed with a feeling of finality, even inevitability. Here was a powerful sensibility at work, at once assured, vital, and subtle, qualities which no reproduction could adequately convey.

I had the same sensation of seeing a work as if for the first time with the portrait hanging beside it, Madame Amédée (Woman with a Cigarette), painted two years later. This depiction of a heavyset woman in a black dress, hand on hip and a cigarette dangling between her fingers, gives little clue in reproduction to the force of her personality at a distance of five feet. That air of disdain, those raised brows, the puckered mouth—could there be a hint of self-doubt in her pose? The impression is reinforced by the artist’s sloping floor and the realization that his model is not actually sitting on her chair but floating above it. Hauteur, insouciance, pretense—all this melts before the penetrating gaze of the artist, who has made his feelings known with such delicate irony.

If it is clear that Modigliani disdained his subject, the same cannot be said for Gypsy Woman with Baby. This first attempt at a mother-and-child theme, painted in 1919, soon after Modigliani became a father himself, could not be more of a contrast. Instead of the heavy outlines and uncompromising pose, here are pastels that seem to float across the canvas. Fragile grays, going from blue to green, are harmoniously intertwined within outlines that have been softened and blurred, the paint broken up into thumb-like patches of color. The mother, hardly more than a girl, with her high coloring, skewed nose, pretty mouth, and sweet, lost look, presses her baby against her as if clinging to a life raft. The effect is poetic as well as endearing; no wonder it was one of the first Modiglianis Maud Dale persuaded her husband to buy. As a final, masterful touch, the artist has added, in his subject’s otherwise neat coiffure, a single escaping wisp of hair.

I arrived at length at Modigliani’s portrait of Chaim Soutine, who was still only a boy when he escaped from Russia and came to Paris to study art in 1913, meeting Modigliani shortly thereafter. Soutine, one of eleven children of cruel parents, barely escaped with his life. Penniless, crude, inarticulate, he was befriended by Modigliani, who painted his portrait a number of times. Here he is, staring out of the frame, a seated figure with tumbling hair and ill-matched clothes, his hands placed awkwardly in his lap, his eyes half closed and peasant nose spreading across his expressionless face. He is ugly, and yet. As Kenneth Silver wrote in The Circle of Montparnasse, “Modigliani manages … to convey a kind of poetic beauty in his sitter, that special brand of idealization for which he is justly famous.”

This same ability can be found in Modigliani’s chef d’oeuvre, Nude on a Blue Cushion, one of the painter’s series of grand horizontals, painted three years before his death. Whatever I had seen or remembered of this work from catalogs was again a pale reflection of the work’s power at close range; this one, in a frame of dull gold with inserts of black, dominated the room. The girl’s limbs are softly rounded, her thighs full, and the outlines of her breasts delineated with a fine black line, nipples blushes of pink. She is half lying, half-raised on one arm, and a hand touches her face, which is turned toward the viewer with a smile. This is a girl who wants to be liked and is not at all sure of the reception, as is suggested by fastidious painterly details, such as the light and shade around the forehead, a touch of pink beside the nose, and the hint of a line under one eye. At close range, one discovers so many of these unexpected touches: the smidgen of blue on a wrist which picks up the color of the cushion, the patch of pink on a knee, the dot at the corner of an eye, and the same judiciously considered background.

All master portraits have a sense of inevitability about them—one thinks of the personalities so brilliantly memorialized by John Singer Sargent—but as I looked around the room it seemed that more was being said than a probing of personality alone, or even painterly experiments in compositional techniques and simplified forms. There had to be a clue to the riddle. I looked again at the single piece of sculpture, a limestone head of a woman, standing on a pedestal in one corner of the room. The head, carved from a rectangular piece of stone, was consequently elongated, its nose radically long, mouth barely indicated, eyes enigmatic and impassive. One thought, as Bernard Dorival wrote, of the religious power found in Khmer and Chinese sculptures. Monumentality—otherworldliness—the transcendental—such thoughts rose to the surface and whirled around in my head. As I knew, an interior stir was the first sign that one’s point of view would be turned upside down and transformed by a new experience. An artist capable of inciting such thoughts had to be something of a magician. And yet, was this someone one would have to know well in order to know him at all? I had to find out.

The response Modigliani’s work had aroused in me was hardly unique. In the years immediately following his death in 1920, a few dealers, critics, and collectors were determined to educate a more or less indifferent public. Maud Dale saw to it that her husband Chester would become the largest single collector of Modigliani’s work and wrote a monograph. So did Giovanni Scheiwiller, a critic and dealer, whose connections with Modigliani’s family began soon after his death. Paul Guillaume, one of his two dealers, wrote an appreciation, and others, among them Jean Cocteau, Adolphe Basler, and Louis Latourette, began to publish their own accounts.

In 1926 André Salmon, poet and journalist, published a seeming celebration of Modigliani’s art that made frequent references to the artist’s apparent addiction to drugs and alcohol. The same stories were repeated in Artist Quarter by Charles Douglas (the pen name of Lawrence Goldring and Charles Beadle), published in London in 1941. Biographers were divided between those who saw him as a true pioneer of modern art or, as with Gauguin, van Gogh, and Soutine, the prototype of an artist at odds with society. He was a visionary, a poet and philosopher, even a mystic. Or he was a minor character, whose romantic life story had led some to place more importance on his work than it deserved. His nickname was Modi, which Salmon was the first to transmute into “maudit,” i.e., accursed. This unrelenting view painted him as morally defective, one of those pathetic figures who disintegrate before one’s eyes. Biographies, films, and plays following World War II were variations on the label that had firmly attached itself: “maudit,” accursed.

Modigliani, the youngest of four children from an educated but impoverished Italian Jewish family, came to Paris in 1906 at the age of twenty-two to make his fortune. Polite, well mannered, intellectual, he soon abandoned the conventional attire of the young bourgeois for the uniform of the Bohemian. Arthur Pfannstiel, writing in 1929, called him “this young Tuscan, this great lyricist, at once draughtsman, sculptor, painter.” He was strikingly good-looking. “How beautiful he was, my God, how beautiful!” Aicha, one of his models, said. He was ardent, impetuous, and not very careful. At least three illegitimate children are likely and stories were told of a courteous, charming personality who became ugly when drunk, took off his clothes, picked fights, and, it was said, threw one of his mistresses through a window. He alienated and dismissed would-be collectors; he was his own worst enemy. Cocteau wrote, “There was something like a curse on this very noble boy. He was beautiful; alcohol and misfortune took their toll on him.” The more he struggled, the more desperate he became. Kenneth Silver wrote, “The little Jew from Livorno becomes a good-for-nothing.”

Modigliani’s difficulties were not only confined to poverty and finding a dealer. Romaine Brooks, whose milieu was the high intelligentsia, received full and flowery mention for her first one-man show, whereas Modigliani had no reviews at all for his in 1917, and few mentions in the French press during his lifetime. But she was rich, he was poor, and art reviewers were notorious for expecting to be paid.

Modigliani, aged thirty-five, died in agony and supposedly starving. His lover, Jeanne Hébuterne, then eight months pregnant, committed suicide barely two days later. His death was bad enough, but hers was almost Greek in its tragic dimension. They left behind a two-year-old girl. They were star-crossed lovers whose brief, haunted lives seemed made to order for the “vie romancées” and “vie imaginaires” so popular in the 1920s. Such fictionalized works were vastly preferable to the prosaic reality, Salmon wrote in Modigliani, sa vie et son oeuvre (1926) and expanded upon relentlessly for decades. In his biography of Beatrice Hastings, Simon Gray observes that Salmon’s frequently quoted La Vie passionnée de Modigliani, written thirty years later, in 1957, is actually a novel but was abridged and reprinted as fact in 1961 under the title Modigliani: A Memoir. Those who were witness to events were appalled at the exaggerations, distortions, and imaginary dialogues that appear in Salmon’s books about Modigliani. Pierre Sichel, a highly respected biographer who published his own account in 1967 when many of Modigliani’s contemporaries were still alive, wrote of La Vie passionnée de Modigliani, “In this book Salmon … devotes well over ten pages to long, imaginary conversations that Modigliani, Ardengo Soffici, and Giovanni Papini had in Venice,” and describes in minute detail the visit of the three to the Uffizi Gallery. Soffici subsequently wrote, “What my friend André Salmon has written concerning the relationship between myself, my friend Papini, and Modigliani contains so many inaccuracies that I must attribute it to failing memory.”

Other authors were not so kind. Jean-Paul Crespelle, author of Modigliani: Les Femmes, les amis, l’oeuvre, of 1969, wrote, “One marvels that the energy he directed at evoking, in so many books, the figure and work of Modigliani has led him to accumulate inexactitudes and inventions. Can one attribute to a failing memory his assertion that Emanuele Modigliani conducted the funeral service … when, as a socialist deputy in the Italian Chamber … he was prevented from visiting Paris until a month later …? Everyone knew this to be true and a simple check would have prevented Salmon from making a monumental error of this kind.… Examples of similar inexactitudes and a total indifference to the truth are numerous. Without any doubt André Salmon, who lived for many years in Apollinaire’s circle, believed, like the poet, that ‘the truth held no interest.’ ”

All this could be easily explained, according to Lunia Czechowska, friend of Modigliani’s final years and subject of many of his portraits. She wrote, “Modi and Salmon detested each other. They refused to say a word to each other. Salmon was contemptuous of this ‘drunken tramp’ and never went to Zborowski’s to see his paintings.” Salmon’s view of the “peintre maudit,” the “dear wounded prince,” has influenced everything written about him since; it fitted too well into popular notions of art as synonymous with eccentricity and even derangement.

But perhaps the most destructive of the falsifications surrounding Modigliani’s life was the French film Montparnasse 19, shown in the U.S. as Modigliani of Montparnasse in 1958. It was based on a novel, Les Montparnos, by another shameless teller of tall tales, Michel Georges-Michel. Gérard Philipe, a classically trained actor, versatile, charming, and boyishly handsome, seemed an ideal choice for the leading role, and the fact that he shortly afterward died, at the same age as Modigliani, lent the portrait a pathos no one could have anticipated. But, Bosley Crowther wrote in the New York Times, the film’s proposition was “that its hero is a lush, sad-eyed, tormented garret dweller who is inexplicably bored and finds bleak comfort with a rich mistress … the victim of idiots and ghouls.” The inevitable death scene, Crowther wrote, “leads one to suspect the scriptwriters … were more impressed by the commercial irony of the artist’s misfortune than by his personal tragedy.” Anna Akhmatova, the Russian poet who had a love affair with Modigliani, was another witness to events who was appalled by the distortions. The film was “extremely vulgar,” and her comment: “It is so bitter!”

Trying to sell his drawings: Gérard Philipe in the title role of Modigliani of Montparnasse, 1958 (image credit 1.3)

The characterization gave further weight to “an art historical mindset that survives to the present day,” Maurice Berger wrote. A demonstration of his point appeared in a London review of the exhibition “Modigliani and His Models” at the Royal Academy in the summer of 2006. The art critic for the Guardian, Adrian Searle, wrote, “Drunken, ranting and stoned on one thing or another—add hash, coke, ether and opium to the alcohol—Modigliani, the archetypal accursed artist” was someone he could not like and who only irritated him. No wonder, Silver wrote, Modigliani was “probably the most mythologized modern artist since van Gogh.”

No one seems to have noticed that the fact that Modigliani was alive at all was something of a miracle. From childhood he had been beset by illnesses and two were life-threatening, and all this before he reached the age of seventeen. It was as if he, along with others in his family, were the survivors of some great catastrophe. Even biographers like Pierre Sichel, who tried to repair the damage caused by the casual distortions of Salmon, Carco, Georges-Michel, and others, and who knew about Modigliani’s lifelong battle with tuberculosis, hardly mention it and seem oblivious to the toll it exacted: physical, emotional, and social. June Rose, another biographer who attempted to separate the reality from the inventions, did not find the illness significant. Neither did Jeanne Modigliani, who wrote his biography, Modigliani: Man and Myth (1958), and barely mentioned the disease that killed him.

As I knew, a biography can never be absolutely, objectively true, “definitive,” as it used to be called. “The reflection cast back by any good biography resembles one of those compound faces made by newspapers for the amusement of their readers, blending perhaps an artist’s eyes and forehead with a criminal’s nose and mouth,” Julian Symons wrote. “The features in a biography are all distinct enough, and they are recognizably the features of the subject: but the haunted eyes and the hunting nose, the wafer-thin mouth and rocky chin, are the biographer’s own.”

What I also knew was, as W. B. Yeats wrote, “There is some Myth for every man which, if we but knew it, would make us understand all that he did and thought.” If it were possible to understand something of the trials Modigliani underwent in the struggle to create and the role his art played in the fulfillment of an ideal, then the enquiry would be worthwhile. As Yeats also observed, “The painter’s brush consumes his dreams.”