“Dedo”

I am borne darkly, fearfully, afar…

—PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY, “Adonais”

JEANNE MODIGLIANI’S early memories of Livorno center around that huge, black, marble-topped table in the kitchen, where, in the first light of dawn, she drank her café au lait and reviewed her lessons before school. She remembers the dining room where, between the Benozzi Gozzoli reproductions, five fading drawings by her father wilted in the lamplight and where, on a fake Renaissance table, a copy of her father’s death mask was displayed on a black velvet cushion. She recalls the scrap of brown corduroy velvet, all that remained of her father’s jacket, now a humble shoe cloth. In family albums Jeanne appears as a fat-cheeked baby, wearing a frilly lace cap and a bib, soon after she had been taken in by her father’s family. Two or three years later she is seated on a balcony with her grandmother, her rounded features expressionless, her hair tightly plaited and bedecked with ribbons. Eugénie, now white-haired, sits beside her wearing a half-smile, her chin defiantly lifted.

Eugénie and Flaminio Modigliani just before Amedeo Modigliani’s birth, 1884 (image credit 3.1)

After the somber glory of the house at 38 via Roma, to move to modest quarters in a nearby street, the via delle Ville (now the via Gambini) was a distinct demotion. Eugénie dealt with it with her usual aplomb. The older she became, the more her rapidly expanding form pushed past whatever shackles convention had placed upon it. She might feel the humiliation intensely; she would never show it. Flaminio, however, was clearly devastated. His wife was almost used to the random malevolence of fate, which had visited so many calamities on her from no fault of her own. He, however, in this particular case had played a central role.

In a photograph taken in 1884 at the height of the crisis and just before Amedeo’s birth, Eugénie is half-turned, away from the photographer; Flaminio’s face is blank, shoulders slumped. His disgrace was compounded by the fact that he had been one of the chief architects of the Lumbroso financial agreement. It was nobody’s fault exactly, but thanks to him his wife and children were penniless. Eugénie can be seen reaching across the gap between them to rest a conciliatory hand on his shoulder. Llewellyn Lloyd, who met Flaminio when Amedeo (called Dedo) was an art student, described him as “a fat little man who always wore a swallowtail coat and a bowler hat” and was very cultured, although how true this was seems in doubt. Some biographers thought that Eugénie and Flaminio eventually separated, although this is also a moot point. The letters of Giuseppe Emanuele—unlike Dedo, Eugénie’s oldest son was a voluminous correspondent—reveal that his father was a continuing presence, even if their mother remained the dominating influence in their lives. When Flaminio died, a year after Eugénie, with what seems to have been an advanced case of Alzheimer’s, Emanuele, searching for a generous summary of his father’s life, remarked that he “was tenacious at work and at doing his duty.” They could remember him as someone who always stood beside their mother, “her gruff, but faithful companion—a bit old-fashioned, but infinitely affectionate and deeply, passionately in love.”

As they grew older Eugénie’s younger sisters, Laure and Gabrielle, also took up residence in the Modigliani household, not that Eugénie was particularly happy about two more mouths to feed. Like Clémentine, Eugénie also played the role of little mother, and her diary makes it clear she had never liked her sisters (or, at least, being made responsible for them). Laure appeared in 1875 and Eugénie had nothing good to say about her. “She was pale and thin, poorly developed and anemic; already a hopeless dreamer, locked up inside herself.” The word “hopeless” is instructive—Eugénie did not believe in this unpropitious cause. Here was the type of girl “without … any kind of inner goal, unsociable, solitary by nature and sickly.” Why had Laure not moved in with Clémentine in Tunisia? She might have turned out better.

Nevertheless Laure stayed for three years, leaving just after Umberto’s birth in 1878, and was replaced by Gabrielle. That was not much of an improvement either. One of Flaminio’s relatives told Gabrielle bluntly, “They sent you here to get rid of you.” It was unkind but probably true. What happened in the intervening years is not recorded but by 1886, eight years later, both sisters were living with Eugénie and grudgingly tolerated. Laure was teaching French, so at least she was paying for her keep. Gabrielle was in charge of the household. “She is doing it well and since she’s had the job it seems to me she is happier, more serene and puts up with little annoyances better,” Eugénie wrote.

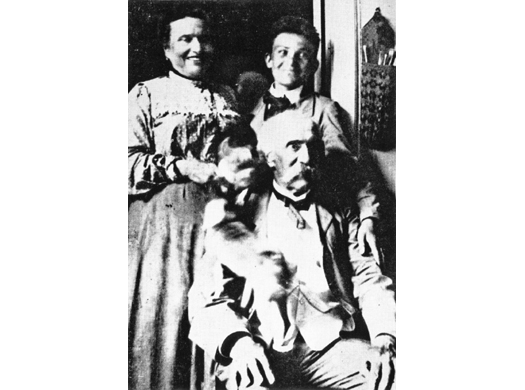

Dedo with his nurse (image credit 3.2)

Since Flaminio’s income had vanished Eugénie had transformed herself and her sisters into teachers of a language they all spoke with ease. Thanks to their social contacts they had attracted paying pupils. Meantime, the children were growing up. Emanuele, always called “Mené,” at thirteen and a half was in high school, serious-minded, intelligent, and doing well. Margherita, aged eleven, was paler and thinner than her mother would have liked, but also making progress. Umberto, gentle and affectionate, was eight years old and not particularly interested in his work. As for the two-year-old, Dedo, he was a ray of childish sunshine. “A bit spoiled, a bit wayward, but “joli comme un coeur,” she wrote. (As pretty as a heart.)

“Joli comme un coeur”: the same had probably once been said of Papa, who had, like Laure and Gabrielle, arrived for dinner in 1886 and never left. Photographs of Eugénie’s father Isacco have not been found, but her description of him as a young man, very handsome, not particularly tall but well proportioned and with clear, expressive eyes, is instructive. His beautiful manners, elegant gestures, and air of effortless distinction, that of a natural aristocrat—all this would come to be said of his grandson Amedeo. Eugénie must have noted the same regular, even features, the same prettily marked eyebrows, the pouting, perfect mouth, and the shock of black hair. If Emanuele, with his wide, square face and stolid build, was born to favor the Modigliani side of the family, it must have been clear to Eugénie that Dedo was a Garsin, quick-witted, energetic, full of charm, small, and slim. No wonder he was already being spoiled.

When written records are sparse the biographer is forced to fall back on whatever can be learned from photographs. The earliest has Amedeo, perhaps a year old, wearing only a shirt and no underpants, much less the diaper with which any self-respecting baby now greets the world. He is sitting in the lap of his nurse, who is wearing the traditional striped dress of her profession. Dedo has probably just come from his bath and looks with bewilderment on the world around him. No other photograph of the baby Dedo is available to us, but like many boys his appearance would have been feminized; boys wore the identical outfits of girls and their hair was not cut until they were three or four years old. They “played freely under their mother’s or servant’s skirts,” and, then as now, their toys would have been scattered everywhere. In Dedo’s case, having a nanny indicated a certain improvement in the family status, if not the platoons of servants once deemed essential for a Modigliani.

It is clear from Eugénie’s diaries that her life had been transformed by the growing success of her teaching enterprise. Her little school was developing from language coaching into an actual establishment, employing other teachers and attracting children from ages five to about fifteen. As soon as he was old enough Dedo, too, was taking lessons, but at home. In Italy as in France, there were few schools for young children, and mothers routinely provided their early education. At age five Dedo could read and write and was probably bilingual as well—in years to come, his command of French would be much admired, and he always wrote to his mother in French. As for the atmosphere of the house, nothing has been written, but one guesses it was tolerant enough. If earlier generations accepted corporal punishment as a matter of course, in bourgeois families, “exchanges of affection between parents and children were tolerated and even desired … Caresses were considered appropriate in many circumstances, an encouragement to the development of young bodies,” Michelle Perrot wrote in A History of Private Life. The fact that the familiar “tu” was coming into use between parents and children, replacing the more formal “vous,” was another welcome development. Less emphasis was being placed on rote obedience and more on an enlightened awareness of the individual child’s needs.

In a household run by women there were male figures to compensate for the lack of a strong paternal influence. The first was Rodolfo Mondolfi, a well-known teacher at a Livornese high school, who appears often in Eugénie’s diaries, helping the boys with their homework, advising her on how to deal with Laure, and, most of all, acting as confidant.

“He is a dreamer,” she wrote, “a man who lives only in books although the necessities of life force him to untiring efforts.” Mondolfi was married with children of his own. “He gives 12 or 13 hours of lessons a day and in spite of it, his head is in the clouds. Very good-hearted, very discerning … He strives for good but does not always find the right road.” Still, she would not judge him. “I love him very much, admire him even more and owe him my deepest gratitude. He was my friend during some sad times … and the one who pushed me towards teaching. To him I owe whatever peace of mind I have found.” Her frank evaluation of Mondolfi’s influence does not mention that he was a leading spiritualist, another strong point of contact. He was at the house so often one is led to posit that he was the ideal companion she had never found. Loving him, she loved his children. His son Uberto became Dedo’s best friend and constantly there as well. Eugénie called him her “extra” child, perhaps expressing a more or less conscious wish.

Despite his years managing a bank in Tunis, Papa had been permanently scarred by the disasters of losing a wife and the Garsin business collapses. In 1886, after Clémentine’s death, he also moved in with Eugénie and stayed there until his death ten years later. As an influence on Dedo he presents a mixed blessing. One thinks of his easy charm, his delicious manners, his facility with languages: Italian, French, Spanish, Greek, Arabic, and some English. One thinks of his enormous erudition. There is also the fact that he was emotionally fragile, “an embittered, irascible old man, suffering from a persecution mania,” Jeanne Modigliani wrote, someone capable of believing that he was being conspired against by a gardener. How many irrational outbursts, how many explosions of rage Dedo may have witnessed, cannot be known.

What is known is that Isacco was an important influence on Dedo’s intellectual development until he was twelve. He had more time for him than his harassed mother, and they would take long walks along the harbor while Isacco gave full rein to his passion for abstract speculations about history and philosophy from which his grandson may have extracted some snatches of meaning. Isacco, who was a great chess player, may have taught it to Dedo, or recited passages in Dante, or sung Italian ballads, and saw to his religious education, preparing him for his bar mitzvah. Perhaps he taught him, as it is said, “Tova toireh mikol sechoireh”: “Learning is the best merchandise.” His other grandsons, Emanuele and Umberto, found such subjects intensely boring. They sensibly preferred sailors, soldiers, ships, and guns; but in Dedo, Isacco had found a kindred spirit.

Although he appeared infrequently, Amédée Garsin is another figure who had a direct influence on Dedo. His name crops up often in “L’Histoire de notre famille” because he was Eugénie’s favorite sibling. He was “so gentle, so delicate and so agreeable. He was a comrade. He understood me.” When he did well in school she was delighted. Whenever he was ill—a bout with typhoid left him with a lesion on one lung—she panicked. She lived for his letters, and if she did not hear from him was full of anxious foreboding.

A photograph of Amédée Garsin as an adult shows him as dark-haired, with a broad forehead, deep-set eyes, and a neat moustache and goatee. Born in 1860, he was thirteen when the family crash came. He finished his studies at business school and was apprenticed at a young age. Like Clémentine, he was short and slim. But, unlike other Garsins, he had an effortless ability to make money. Jeanne Modigliani wrote that whenever Uncle Amédée arrived for a visit in Livorno, “his passage always left behind a breeze of fantasy, generosity and warm enthusiasm.” Thanks to him, Emanuele went to the University of Pisa and became a lawyer. Umberto took his engineering diploma at the University of Liège. Amédée took as much interest in them as if they had been his own sons, and since he never married, in a way they were. The handsome young uncle, who arrives loaded down with presents and slips money into people’s pockets, demonstrated how a successful actor deals with life. “[The show] is often enacted … for the promotion of the actor’s interests and those of his family, friends and protégés,” Luigi Barzini wrote in The Italians. “How many impossible things become probable here, how many insuperable difficulties can be smoothed over with the right clothes, the right facial expressions, the right mise-en-scène, the right words?” Everyone wanted to look well off even, or especially, if they were not. The art of appearing rich, Barzini continued, “has been cultivated in Italy as nowhere else.” Nonskilled workers who achieved their first steady jobs spent their money on superfluous and gaudy purchases. “Apparently the things they want above all are the show of prosperity and the reassurance they can read in the eyes of their envious neighbors. Only later do they improve their houses, buy some furniture, blankets, sheets, pots and pans. The last thing they spend money on is food. Better food is invisible.”

An undated photograph of Uncle Amédée Garsin (image credit 3.3)

Amédée was rich, except for all the times when he was not. According to Margherita he made and lost three fortunes. There were factors at work here that she failed to understand: his reckless indifference to money and the way he seemed compelled to gamble it away. In that respect, Amédée Garsin was following a long tradition that reached its apogee in the eighteenth-century gaming salons of London, Paris, Bath, and elsewhere. Throwing money away was aristocratic. Throwing money away showed just how limitlessly rich you were. The daredevil coolness involved was admired, then as now, as evidence of manliness and superior breeding. A talent for acting; the cultivation of seigneurial indifference to money—such lessons were not lost on Dedo.

Uncle Amédée did not pay for Margherita’s schooling because she did not have any. In the Garsin family, women were not completely ignored—they might be allowed to study, so long as it did not interfere with their roles as wives and mothers—but in all essential ways this was a family that was all for its sons and neglected its daughters. Women stayed in their assigned places, as Clémentine did. Eugénie also accepted these limitations until circumstances forced her to do otherwise. She went from being a liability to being a financial asset and acquired the confidence that accompanied her new status. She was lucky. She had male support and recognition, not just from Mondolfi, for the gifts she would continue to explore, translating Gabriele d’Annunzio’s poetry into French and writing novels and short stories under a pen name. Her essays on Italian literature were good enough for an American professor to buy and publish—under his own name, of course. If she was ahead of her times her sisters, lacking the same emotional support and validation, were floundering. Unmarried, they shuttled from house to house, feeling stifled, unappreciated, and blocked, taking refuge in a kind of neurasthenia common to intelligent women who have caught a glimpse of a wider world and then been barred from entering it.

The young Amedeo was being brought up in an atmosphere of genteel poverty. On the one hand there was the Modigliani heritage of palatial rooms, servants, meals, and the homage due to the reigning monarch of such an establishment. On the other, there was the reality of the cramped little house on a back street, the scramble for money, the menial chores, and the social status they nevertheless felt was their due; one sees it in the defiant tilt of Eugénie’s head. The result seems to have been, for the Garsins, an intensified love of learning for its own sake. Books were Dedo’s companions. He lived among them, especially Les Animaux peint par eux-mêmes, a book on animals illustrated by Gustave Doré. Dedo would spend hours embellishing the original plates with his own color schemes, presumably to general approval.

Amedeo Modigliani, caught telling a joke to Giovanni Fattori, grand old man of the Macchiaioli school of Italian painting, with Fattori’s wife (image credit 3.4)

Commentators on Modigliani’s life believe he showed no interest in art until he was fourteen. This seems implausible, since histories of artists demonstrate that, like musicians, they begin exploring their talents early in life. Modigliani’s brother Umberto told June Rose, one of Modigliani’s biographers, that Dedo drew from childhood; lacking paper he would take over the walls and, presumably, floors as well. His happy ability to improvise on anything and everything, including china and furniture, bears witness to a natural gift. Photographs of the period, requiring that the sitter remain motionless, give one little clue to temperament. A school picture of about 1894 shows Dedo in a group with eight youngsters, all wearing a military-style shirt with button trims, belts, and dark pants. Dedo, hands at his sides, stands at attention, his face a blank. But there is a later photograph, blurred and undated, that is a revelation. Dedo has been caught telling a joke; his eyes dance with mischief and quicksilver charm. In the hunt to find the real person the smile is a minor but revealing clue. As for Eugénie, she knew Dedo was intelligent, probably spoiled as well. She wondered what kind of personality lay inside the chrysalis. “Perhaps an artist?” she wrote with prescience. Dedo was eleven.

The year before, in 1894, Dedo had entered his first school, the Ginnasio F. D. Guerrazi (grammar school), where Eugénie’s friend Rodolfo Mondolfi taught. A boy who is not in school and goes on exploratory walks with his grandfather soon knows the map of a town like the back of his hand. Livorno, or Leghorn, would have been a rewarding discovery in Modigliani’s childhood, but there is not much left of the old town nowadays. Livorno suffered heavy damage during World War II and has largely been rebuilt since. One imagines it as once like Marseille, a twisting network of streets leading off the old port. Livorno had been a major port on the Ligurian Sea since the sixteenth century and rose to prominence after Pisa, its Mediterranean neighbor twelve miles to the north, silted up. On the one hand it developed as a center for shipbuilding and heavy industry; on the other, as a tourist attraction, with massed banks of flowers along the promenades. Somehow Modigliani’s birthplace on the via Roma has escaped destruction and is now a museum. There is a large synagogue, established in the sixteenth century. There is also a Protestant cemetery with tombstones bearing such names as Lockhart, Murray, Ross, and Lubbock.

Pisa and Livorno have a long and romantic history as magnets for a British colony of writers and poets. Tobias Smollett, who wrote Humphrey Clinker at nearby Antignano, died in Livorno in 1771 and is buried at the Protestant cemetery. Early in the nineteenth century it was fashionable for the British literati to explore the Ligurian coast in yachts, a vogue that was adopted with enthusiasm by Byron, who was eternally restless and wealthy enough to build his own. In pursuit of picturesque views and the perfect sailing waters the British poet wandered up and down the Ligurian coast, renting one spacious villa after another. In the summer of 1822 he and his entourage were ensconsced in a villa in Montenero, a hilly suburb of Livorno that could only be reached by a funicular, with spectacular views over the Mediterranean. There Byron was joined by Leigh Hunt, poet, journalist, and critic, with whom he was engaged in launching a new magazine. Hunt, his wife, and six children settled in for a long visit, there to be met by Percy Bysshe Shelley, who had moved to Italy with his family and was living further up the coast in an unused boathouse at San Terenzo. Shelley was then working on his last major poem, “The Triumph of Life.” He was twenty-nine years old.

The via Vittorio Emanuele, one of the central shopping streets in Livorno at the turn of the twentieth century (image credit 3.5)

Early in July 1822, Shelley set sail in a new boat, the Ariel, built for him by Byron, fast and luxurious but an open craft with no deck. He made the fifty-mile trip to Leghorn in about seven hours, and stayed for a week. Then he, a friend, Lieutenant Edward Williams, and an eighteen-year-old cabin boy set out on the return journey. There was a violent storm. The boat capsized and all three were drowned. Their bodies washed up on the beach at Viareggio ten days later and were cremated on the spot, with Byron in attendance. Shelley’s partially decomposed body was recognized by a book of Keats’s poetry that was found in his pocket.

The port of Livorno, from a postcard sent by Modigliani to Paul Alexandre (image credit 3.6)

Shelley had written an elegy, “Adonais,” the name he gave to Keats, who had died of tuberculosis the year before at the age of twenty-four. Shelley’s lengthy poem mourning the loss of a great poet ends with a curiously prophetic stanza:

[M]y spirit’s bark is driven,

Far from the shore, far from the trembling throng

Whose sails were never to the tempest given;

The massy earth and sphered skies are riven!

I am borne darkly, fearfully, afar;

Whilst, burning through the inmost veil of Heaven,

The soul of Adonais, like a star,

Beacons from the abode where the Eternal are.

“I am borne darkly …” Judging by a photograph of the Ginnasio F. D. Guerrazi student body presumably taken the year Dedo entered it (1897–98), the grammar school boys, ranging in age from ten to about fifteen or sixteen, were either split into small groups or in one large class, with individual curricula depending on their rates of progress. A report card for the same academic year shows that Dedo was studying the standard humanist subjects: Latin, Greek, and French, in addition to Italian, with courses in geography, mathematics, history, and natural history. Students were being graded on gymnastics, but that part of Dedo’s report card is blank. In fact, the boy in the picture, squeezed between classmates in the front row, had already had his first serious illness.

Sometime in the summer of 1895, when he was eleven, Dedo developed a chest pain so sharp and persistent that it hurt to breathe. Perhaps he also had a moderate fever and a dry cough. Perhaps his lungs were filling with a clear fluid. The diagnosis was pleurisy and he was put to bed, a tape wound tightly around the lower part of his chest. Dedo slowly recovered, but Eugénie wrote in her diary that his illness gave her “a terrible fright.” She might have known, or guessed, that this illness was an ominous sign.

During the next two or three years, Mené obtained his law degree, Umberto acquitted himself well at the University of Liège, and Margherita, aided by her mother, showed promising signs of becoming a scholar herself. Laure had taken up writing and translating. Gabrielle stayed with friends for awhile and then returned, but was in a stubborn mood. Eugénie wrote in the early summer of 1897, “Gabrielle neglects almost everything”—by that she meant her sister’s household duties—“to give herself up to orgies of piano playing.” It would seem Gabrielle had conceived the ambition of becoming a professional musician, and “in order to run after an impossible ideal, the poor child neglects to make herself useful. I have not the slightest influence over her; she flares up at the smallest word and even accused me once of deliberately trying to make her unhappy.” Dedo’s grandfather had died the year he went to school. Eugénie wrote, “My poor father had suffered greatly before dying. But he … left this world where he had so many blighted hopes with a serenity that comforts me, and makes me think his death was a deliverance.” Meanwhile, two years after his attack of pleurisy in 1895, the thirteen-year-old Dedo had passed his bar mitzvah and was ready to launch himself into life, or so his fond mother believed. That year, Dedo did not do well in school, but then, he had hardly bothered to study. The year before, he had decided on his future career. She wrote in July 1896, “He already sees himself as an artist.” He was now twelve years old.

Not enough is known about Laure and Gabrielle to explain their sad eventual fates. In 1915, the year Gabrielle committed suicide by throwing herself from the top of a staircase, Laure was admitted to a mental hospital. The situation is complicated by the fact that, in the nineteenth century, calling a woman insane was often a convenient way of getting rid of her. A sense of frustration was seen as a perverse refusal to be happy, arguing with a husband a sacrilege, and rebelling against her natural roles as dangerous. As Michelle Perrot wrote in A History of Private Life, excuses of this kind were enough to lock up obstreperous women in mental institutions because of “a private tragedy or family conflict of which the physician was the sole judge and arbiter.” Adèle Hugo and Camille Claudel, for instance, were “apparently … confined as a result of arbitrary decisions on the part of families intent on safeguarding the reputations of two famous men.” It is worth remembering that, in France, women could not vote until 1944 and in Italy, until 1945.

One has to believe that whatever troubled Laure and Gabrielle was not understood and dismissed if only because the insurrection of daughters, sisters, and wives was a taboo subject. Eugénie’s account omits all such speculations. Laure is hopeless, an introvert and a dreamer. Gabrielle, who ought to be helping them, is embarked on the ridiculous ambition to become a pianist. As for Margherita, despite Mené’s loyal references to his pretty sister, she does not appear as attractive in photographs and did not marry. She is competing with three brilliant brothers, one of them ill so often that her mother can hardly think of anything, or anyone, else. And Eugénie was always prepared for the worst. She had seen too many people die not to view life through a prism of rage and loss. In 1891, when Dedo was seven, she wrote a poem that would seem to be the response to some kind of business disaster in her brother Amédée’s life. He may even have been sent to prison. She called the poem “Fierce Wish”:

I wish to proclaim the Kingdom of Force:

To hang a Jew on every tree

To loose from prison every thug,

To flay every person of virtue.

To snatch from Aunt Eugenia the pious Amedeo

Who today soothes her every pain

And compels her to smile sometimes.

To drive all kindness from the earth,

To duck every abstainer in a wine-vat,

To put every clean person in a pigsty

And to annoy and upset my neighbor

And set light to his hayloft

So that his little son suffocates.

Unsure of her mother’s love, Margherita turned in two directions. She was a dutiful daughter, contributing to the family income, caring for Dedo’s orphan, and there to help when her parents became ill and died. But a sense of not being valued also led to a prickly readiness to find herself offended, the “Why me?” lash of her mother’s poem. The family expectation seemed to be of automatic achievement. Failure led to recriminations and a willingness to wound. Ridicule was common and even Mené, the born diplomat, occasionally indulged: “Tell that thing who created us,” he wrote, only half joking, “that if she decides to get upset every time things heat up … I will let a few days go by without writing.” It was time to draw attention to his mother’s rather prominent moustache. It reminded Mené of a wolf that had lost its fur or a leopard that had changed its spots; even when he was trying, true invective was beyond Mené. Then he added the one thing that really was wounding. Their mother was always talking about how brave she was, when she was not brave at all.

A school play. Modigliani, hatted, is in the back row, second from the right. (image credit 3.7)

Sometime around 1895 while Mené was still doing his military service, Dedo, then perhaps eleven, wrote to tell him about their mother’s triumph; her Children’s Theatre had won an award. Mené was ecstatic. How he wished he could have been at the Strozzi Theatre at that moment. In his mind’s eye he saw

the white curtain falling, the drop curtain opening, and our mother appearing there and not leaving (because in the confusion she can’t figure out how to get off the stage)…Mamma must have been wearing something black and perhaps a little bow on her left side (it’s her passion!) and her face must have been very rosy … almost like Piticche [his name for Margaret] on a beautiful day … A simple bow of her head to this side and that—and inside, inside the laugh mother always has when she receives sincere compliments that make her blush and make her happy. And then she stops talking, straightens up and her eyes shine … and the handkerchief in her hand is not just for blowing her nose.

When Mené went to the University of Pisa to study for his law degree he was a monarchist, but by the time he left he had joined the newly formed Socialist Party and the well-being of workers had become a lifelong concern; he was elected a consigliere, or councilman, in Livorno when he was twenty-three. His change of heart was prompted by an awareness of the extent to which the Modigliani family, his father included, had grown rich by exploiting workers in their Sardinian mines. Now he was reaching across class barriers and his life would be devoted to liberal causes, his belief in the dignity of manual labor and votes for women, while his political stance was anticolonialist, pacifist, and dedicated to change from within. Mené imagined the middle-class audience gathered at their mother’s moment of triumph and the polite applause that would have greeted her because she was a wealthy lady who had been forced to work. The fact that they would have pitied her exasperated him. “Too much condescension from idiots!”

During the past year Mené had become aware of how much their parents had gained in a human sense from being obliged to work. “Think about this Dedo,” he wrote. “You must love your parents just because they are your parents. But … you must love them much, much more because they work for you! How many times I have felt like a stranger when I was with workers!” Now he is proud to say, “I am the son of workers, too.”

The fact that his parents worked was something Dedo, too, should be proud of, not ashamed of. Dedo must do whatever he could to make sure that future workers were valued and never forget that he, too, was the son of workers.

Mené was aware, as his letters to Piticche imply, that she, along with most other members of his family, did not share his Socialist views. Some of them would, he wrote, say he was a windbag and would scream at him for saying they were workers too. However much they might quibble with his ideas, when Mené was in trouble he could be sure his family would unite behind him. In 1898 Mené, then twenty-six years old, became editor of a progressive weekly paper in Piacenza at a time when the increased price of bread was causing rioting in the streets. When all of Tuscany was under martial law, everyone was under suspicion, and especially editors of radical papers sure to be fomenting unrest. On May 4, 1898, Giuseppe Emanuele was arrested and went to prison in chains.

A portrait made in 1900 of Modigliani’s oldest brother, Giuseppe Emanuele Modigliani (image credit 3.8)

“We don’t know why he is there or what he is accused of,” Eugénie wrote at the end of June. It was true Mené was an active and militant Socialist, but this was hardly a crime. “My poor darling, he endures with simplicity and real heroism, something that must be doubly difficult, given his youth and expansive temperament … He consoles himself like a Benedictine monk in his cloister, with faith—faith in a very pure and elevated ideal—perhaps too beautiful and unrealistic—but since Mené is not only good but furiously reasonable, I am sure he will find inside himself the way to reconcile his dream with reality.”

Not only good, but furiously reasonable—the evaluation was astute and to the point. In years to come this voluble, optimistic, and self-deprecating politician with a gift for conciliation would become a Socialist deputy and one of the most influential members of his party. But for the moment he was helpless. On July 14, 1898, he was sentenced to six months in prison plus a heavy fine. There were hints of worse to come.

The effect on his family of Mené’s arrest, imprisonment, and sentencing cannot be overemphasized. Eugénie’s diary makes it clear that of all the blows of fate she had endured, this was the worst. The day of Mené’s sentencing she wrote, “The most agonizing day of my life. Today, judgement will be passed on Emanuele in Florence before a military tribunal. I am mad with fear and nervous prostration.” As with all family crises, everyone was arriving. Umberto, in Liège, was cutting short his studies to return home. Laure, who had been in Marseille for two years, was on her way back. Gabrielle was running the household and Amédée, ever generous, was offering to pay Mené’s fine. They all felt with Mené, agonized with Mené, and closed ranks for Mené. The fate of this brilliant young lawyer, already de facto head of the family, affected not just their financial and emotional security but almost their very existence. Eugénie did not collapse, but she suffered. Dedo, her closest and best, with his dawning awareness of the issues at stake, was just as frightened. A month later, in August 1898, he had another serious illness. This time it was typhoid.

It happened just after Laure returned. Dedo had been feeling listless, with headaches, no appetite, and an inability to sleep, but when he suddenly began running a fever the whole household knew what it meant. This was a fever that returned day after day for weeks on end, gradually climbing to a high of 103–104°F. Such a patient is restless, hot, and uncomfortable, his cheeks flushed and his stomach sore. At the climax of his infection there will be great numbers of typhoid bacilli in the blood, and a characteristic skin rash, called “rose spots,” pale pink or rose in color, will appear on his stomach, chest, and back. But the worst damage will be to his intestines, where bacilli attack the body, leaving areas of dead tissue and ulcers. Massive hemorrhaging into the bowel is a real possibility. Further complications are acute inflammation of the gallbladder, pneumonia, encephalitis, and heart failure.

Was Dedo hospitalized? There is no evidence one way or another. But since his recovery would have depended entirely on the quality of the nursing care, the odds are that he stayed at home where Eugénie, Gabrielle, Laure, and Margherita could take turns nursing him. He was hovering between life and death and delirious for more than a month. Then comes an episode that has been discounted as part of the Modigliani “myth.” In a memoir she dictated to her daughter in 1924 Eugénie writes that, at the height of his delirium, “Dedo said he wanted to study painting. He had never before spoken of this and probably believed it was an impossible dream that could never be realized.”

He had seen few actual paintings but plenty of reproductions of Italian Renaissance works. “He spoke of one of his nightmares: he missed the train that was supposed to take him to Florence to visit the Uffizi Gallery. He spoke of Segantini, the most popular painter of the day, with such insistence that his mother, who was nursing him, decided she had to satisfy him whatever it cost. One day when he was still in the grip of fever and delirium, she clasped both his hands and tried to hold his attention. She made him this solemn promise: ‘When you are cured, I shall get you a drawing master.’ ”

This sounds like a fallible recollection made thirty years after the event. (The memoir was published in The Unknown Modigliani by Noël Alexandre in 1994.) Obviously, everyone already knew of Dedo’s interest in art. And Eugénie’s diary of July 1898 makes it clear that Dedo was starting drawing lessons on August 1, 1898. She further notes that he already saw himself as a painter. It is likely that lessons had begun, as Pierre Sichel believed, just before Dedo was taken ill. The essential facts, however, cannot be in doubt; the dream in which you have just missed a train, and an opportunity has passed you by, is too human not to be believed.

What seems likely is that Dedo had never talked so openly, and for the first time revealed his passionate longing to see the actual masterpieces rather than poor reproductions. That fateful year Eugénie had also written that she had been reluctant to give Dedo too much encouragement for fear that (like Gabrielle) “he will neglect his studies to pursue a shadow.” This latest illness had obviously changed her mind and put the emphasis where it belonged, on his present happiness. Eugénie’s account in 1924 ends, “The sick boy understood—confusedly—and from that moment began to get better.”

Emanuele was released from prison in December of that year. It was four months after Dedo’s illness. At that moment, Dedo’s convalescence came to an end. He was back on his feet and ready to begin his life’s work.