The Perfect Line

…and hence through life

Chasing chance-started friendships.

—SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE,

“To the Rev. George Coleridge”

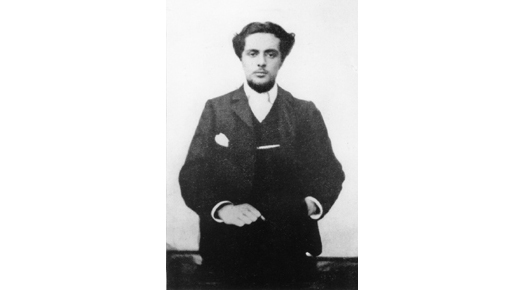

CHILDREN WHO BEGIN as adorable cherubs sometimes have a disconcerting way of losing their looks, their first flowering of physical glory having been their last. Dedo began as perfection: pouting mouth, wide dark eyes, strongly marked brows, and straight nose, and never deviated from that classical pattern. Pictures of the young Modigliani illustrate the mysterious progression by which infant features can metamorphose into a masculine handsomeness without losing one iota of their allure: wider cheekbones, stronger, straighter nose, eloquently large eyes, and full lips. Perhaps because of his devastating illnesses, Modigliani remained what we would call short, five foot three, which was considered an average height for his generation and not regrettable, as it is now. He retained ideal proportions and during his brief career as a sculptor attained a powerful physique.

To say that he was loved by women is an almost laughable understatement. All his life, almost before one affair was over, another began. Perhaps he was also loved by men but there is no evidence of this. As soon as he was studying with Micheli this seemingly shy and delicate boy was turning the conversation to girls. Bruno Miniati, who later became a photographer, said Dedo used to make admiring comments about Micheli’s maid, a pale little girl with eyes as black as coal. To another classmate he said one day, referring to the same girl, “Wouldn’t you like to find a button in your pants because of her?” Still, he would not stay with the others when their walks took them to the via dei Lavatoi or the via del Sassetto, where the brothels were. “Dedo would always turn back. He was ashamed.” Somewhat later, it is said, it was a point of pride for Modigliani to talk about how many brothels he had visited.

The painter Ludwig Meidner recalled, “I think it was in Geneva that a wealthy German woman, who was traveling with her young daughter, invited him to accompany them and Modigliani was quite happy to accept this offer. He had just come from home, and was at that stage immaculately dressed, a lively, good-looking young man of twenty-two years of age who subsequently paid less attention to the … mother than to her youthful daughter. It greatly amused him to flirt with the daughter without the mother noticing, and he never got tired of telling us about it.”

He had, the art critic Adolphe Basler wrote admiringly, “that masculine handsomeness which one admires in Bellini’s pictures.” The blushing shyness, now replaced with calm confidence, demonstrated a polish that would again have reminded his mother of her dead father, along with his characteristic elegance and refinement. Thanks to the continuing generosity of Uncle Amédée, Modigliani at this stage enjoyed all the privileges of a young man of good family who does not need to work for a living, and his dress showed it. It was refined without being showy, while calculated for maximum effect. “A public man, the dandy, an actor on the urban stage, hid his individuality behind the protective mask of appearance, which he strove to make undecipherable,” Michelle Perrot wrote. “He was fond of illusion and disguise and exquisitely sensitive to detail, to such accessories as gloves, ties, canes, scarves and hats.”

What is significant about this observation is the link the author makes between status, costume, and the instinct to perform. Barzini wrote of the Italian male, “Watch him promenade down the corso of any small town at sunset, or on Sunday morning after mass. How cocky he looks, how close fitting are his clothes, how triumphantly he sweeps his eyes about, how condescendingly he glances at pretty girls from the corner of his lowered eyelids! He is visibly the master of creation.” Barzini might have said, but did not, that no one assumed the role with more enthusiasm than one of the poets Modigliani most admired. Gabriele d’Annunzio was equally small and, once his youthful looks had departed, pockmarked and ugly, but women continued to fall at his feet. He had presence, the actor’s gift of entering a room. He had charm, he was a shameless flatterer, and he knew the importance of dressing for the part: first as a curly-locked adolescent poet, then a young man-about-town, then a successful dramatist, the World War I aviator, and, finally, a national hero, marching on Fiume to claim it for Italy in 1919. D’Annunzio cleverly attired his conquering band of fighters in uniform brown shirts, a flourish that was not lost on Mussolini, who merely changed the color, so that his soldiers marched in black ones. D’Annunzio and Modigliani—both wonderfully gifted, idealists to their toes, utterly dedicated as artists—were illusionists, hiding behind a façade. It is difficult to say who became the better master of that art.

Recovered from his brush with death: a prosperous Modigliani, c. 1905 (image credit 5.1)

By the spring of 1901 Modigliani and his mother were back in Livorno after an absence of six months.

At seventeen, Modigliani was at an age when most young men nowadays are still living at home. But in his generation, with its short average life span—by 1913, that had become forty-eight for men and fifty-two for women—and when working-class boys in Britain left school at the age of twelve, seventeen would have been considered adulthood. Going home to live with mother did not suit him at all. Within days he had persuaded her to let him undertake formal studies in Florence. Ever agreeable, Uncle Amédée paid his expenses and Modigliani left Livorno. Ghiglia was in Florence, still studying with Fattori, and they presumably shared a studio. On May 7, 1901, Modigliani began taking life studies in the Scuola Libera del Nudo. He moved to Rome for the winter, returning to Florence early in 1902, presumably to rejoin Ghiglia. Not much is known about these first months of independence but we do know that on his return he contracted scarlet fever. Before the arrivals of penicillin and sulfadiazine this infection by haemolytic streptococci was considered more dangerous than measles and capable of causing serious complications. Scarlet fever, now fortunately rare, began with a fever, a sore throat, and a headache, followed by the arrival of small red spots, redder and more numerous than measles, hence the name. After these disappeared the skin was covered with a powdery substance that made it look as if it had been dusted with meal, and often peeled away. The neck was tender to the touch and the glands were swollen. Upon hearing the news Eugénie again rushed to Dedo’s side. Vomiting, rapid pulse, delirium—these were a few of the possible complications. But this time symptoms were relatively mild and, Margherita records, her brother recovered “without any complications.” Another convalescence followed, this time in the Austrian Alps, and Dedo’s health was again restored.

Modigliani’s exact movements in these years are not entirely clear. But it seems likely that before this latest illness he also studied with Fattori. He took an examination for the Accademia di Belle Arti in Florence and was given permission to copy paintings in its galleries. Eugénie’s memoir, published by Noël Alexandre in The Unknown Modigliani, records that he never attended regular classes and, as before, continued to be largely self-taught. Early letters to the family of this period have been lost. However, they were aware that he spent a great deal of time looking at art books in the Biblioteca Nazionale. Margherita records an incident that took place there, presenting it as proof of her brother’s autocratic and mulish character. She writes that, as he was there one day studying, a librarian accused him of having stolen a valuable book. Modigliani replied with “a volley of insults.” The director was called and was also given a piece of his mind by the eighteen-year-old upstart. The library took legal action and the case went to court. Modigliani’s lawyer was able to prove, not only that his client was innocent, but that the real culprit, the man who stole the book, was the librarian who had accused Modigliani. Margherita was not pleased. She wrote that her brother, who had “abused” a civil servant, would not apologize. Why she should expect Dedo to apologize when he had been wrongly accused, tells us more about her than him.

Modigliani moved to Venice in the spring of 1903 and enrolled in the Scuola Libera del Nudo at the Accademia delle Belle Arti in May. All his life Modigliani made friends easily, and he was making contact with a distinguished group: Umberto Boccioni, the Futurist painter and sculptor, Fabrio Mauroner, with whom he shared a studio in the San Barnaba quarter and whose interests would include sculpture, painting, the graphic arts, and art criticism; as well as artists Mario Crepet, Cesare Mainella, Guido Marussi, Ardengo Soffici, and Guido Cadorin. Such encounters with the cream of intellectual and artistic life in Venice suggest assiduous cultivation. Perhaps it was in Venice that Modigliani learned the pivotal rule for the up-and-coming young artist, the right cafés at the right moment. In Venice it was the Florian, which never closed. Meanwhile he occasionally went to life classes, relying on his eye and the lessons to be had by daily visits to the great museums, studying the Bellinis and Carpaccios with concentration.

He had also met a young Chilean painter, Manuel Ortiz de Zárate, whose Italian was fluent and who liked to boast about his Basque origins. Sichel described him as “a hulking, muscular youth who, with his big head, deep brooding eyes and powerful features, looked older than his age.” Even though he was only seventeen, Ortiz had already been to Paris and fired Modigliani with enthusiasm for this world center of all that mattered in art and sculpture. Like most of Modigliani’s friends Ortiz was barely surviving and intensely envious to find Modigliani living in comfort and wearing a perfectly magnificent pair of pajamas. Modigliani was painting, but Ortiz was not impressed by the results; his work seemed lackluster. In any event, painting was not on Modigliani’s mind just then. Ortiz recalled, he “expressed a burning desire to become a sculptor and was bemoaning the cost of material. He was painting only faute de mieux. His real ambition was to work in stone.”

Jeanne Modigliani, who writes with a delicate understanding of her father’s work, thought he must have conceived the ambition to become a sculptor in Naples, visiting the churches of Santa Chiara, San Lorenzo, San Domenico, and Santa Maria Donna Regina, and discovering the work of Tino di Camaino, the thirteenth-century Sienese sculptor who was head of the works at Siena Cathedral and later worked in Florence. The discovery of Tino’s work demonstrated the successful solution of “those plastic problems with which he would be dealing all through his short artistic career,” she wrote. There was the “oblique placing of the heads on cylindrical necks, the synthesis of decorative mannerism with a sculptural density and above all, the use of line not only as a graphic after-thought but as a means of composing his volumes and holding his masses together in a way that even seems to accentuate their heaviness. From that time on, critics of Modigliani’s work see it as a continual oscillation, which at its best results in a synthesis between the demands of his clean rhythmic line and his love for full, solid and rounded volume.”

Modigliani’s first attempt at sculpture was, however, unpromising. Accounts vary but he would seem to have traveled to the great marble quarries in Carrara, some thirty-five miles north of Livorno, in 1902 or 1903, setting himself in the studio of Emilio Puliti in Petrasanta, a little village five miles away. The fact that he actually accomplished a sculpture is demonstrated by a letter he wrote to Gino Romiti that enclosed photographs of the result, asking Romiti to make some enlargements. When marble proved to be too formidable, Modigliani turned to stone and came up with two or three studies. It was difficult, exhausting work, and so for the time being he abandoned the effort and went back to painting. His sculptures were, of course, all heads.

Eugénie wrote in her diary, “I can’t see yet who he will become, but as before his health is the only thing I think about and in spite of the economic situation I can’t yet give much importance to his future career.” Meantime, her son continued to make friends. “I visited Venice for the first time in 1903,” Ardengo Soffici wrote, and a colleague introduced him to Modigliani. “At the time he was a handsome, kindly-looking young man, of average height, slim and dressed with a sober elegance. He was serenely charming to everyone and spoke very intelligently and calmly.

“During my stay in Venice we spent many pleasant hours together, either strolling round the wonderful city to which he acted as my guide, or in a cheap restaurant he took us to.” Modigliani ate sparingly and drank little or no wine. “There, eating fried fish the strong tang of which I can still smell, my new friend entertained us with talk of his researches into the painting technique of the Italian primitives, his passionate study of fourteenth-century Sienese art, and, especially, the Venetian Carpaccio, of whom he seemed particularly fond.”

Fabio Mauroner recalled that while in Venice Modigliani was painting a large portrait of a lawyer in the style of Eugène Carrière and making studies of the nude models usually to be found in his studio.

“He would spend the evenings, and stay late into the night, in the remotest brothels where, he said, he learned more than in any academy … After a while I had occasion to show him some volumes of Vittorio Pica’s Attraverso gli albi e le cartelle, the first and perhaps the only interesting Italian study of modern engravers and graphic artists.” Mauroner was trying to interest Modigliani in the graphic arts, but without success. “Already during those days,” Mauroner wrote, “Amedeo was looking for the line, which he saw as having a spiritual value in its simplification, as a solution to his search for the essential meaning of life. But while he was in Venice this ambition was hardly more than a vague abstract idea in his mind. The experience of this, and its practice, was still a distant dream.”

One never quite knew, with Modigliani, when a discussion of the practical problems of technique and composition would take a sudden turn and start examining the riddles of existence. One of his letters to Oscar Ghiglia ends with the comment that, when the time came for him to leave Venice, the city would have imparted some unforgettable lessons. What those were, he did not exactly say. “Venice, head of Medusa, with its many blue snakes with their pale, sea-green eyes, where the soul is engulfed and exalts the infini …” Such heady shifts of ground appealed to some friends and exasperated others. Llewelyn Lloyd, his old friend from their student days in Livorno, ran into him one morning in 1905 on the Piazza San Marco. “He immediately began to talk about pictorial and technical problems, going from art to philosophy and other abstruse matters. The day was beautiful, the square enchanting, pigeons flew in great circles over our heads, the Venetian scarves fluttered in the breeze from the Lagoon. I couldn’t take any more, and just left.”

That was the year Dedo became convinced his future lay in Paris, and early that year Uncle Amédée, who had done so much for him, died. Eugénie’s diary entry for February 1905 does not give the cause of death. She wrote that she had just returned from Marseille, where she had been dealing with the papers of her “poor dear Amédée.” She could not bring herself to recapitulate the whole, sad history. “Nothing will fill the void he has left in my life. There was an affection that was too complicated, too often tested, made of pity and trust, and above all from such a complete communion of souls that nothing will replace it.” But she had to keep reminding herself that “he could never be happy and that everything was for the best.” This revelation that the man everyone loved, who was perpetually in a good mood, was actually incapable of happiness, is surprising, to say the least. If, as rumor has it, Amédée committed suicide, Eugenie’s final thoughts support that possibility.

Just how Modigliani survived financially is another imponderable. Parisot writes that Amédée Garsin, then believed to be bankrupt, nevertheless left his nephew a small inheritance, on which he drew for the next three years, supplemented by a small allowance from his mother. It is certainly true that Modigliani arrived in Paris in style, as witnessed by numbers of his friends, who thought he had been left a fortune by a rich uncle. True, he was painting portraits—the subject of the large portrait Mauroner saw in his studio was probably a lawyer named Franco Montini—but how many were actually paid for is also a moot point. Other works, such as a portrait of Mauroner himself, have been lost. Modigliani knew a prominent Venetian family, the Olpers, through his sister—Albertina Olper had been Margherita’s school friend—and is known to have visited them often. His sister also believed Dedo had painted a portrait of Leone Olper, Albertina’s father. When the family wanted to sell the painting in 1933, Giovanni Scheiwiller, an early biographer of Modigliani’s, was asked for help in finding a buyer. However, Ambrogio Ceroni did not include this painting in his accounting of Modigliani’s works, and it has not been listed by other scholars. Modigliani was famously unsatisfied by his own work and it is possible that, when the time came to leave Venice, and to avoid the expense of taking the canvases with him, many of them were destroyed.

Modigliani took very little with him to Paris in 1906; clothes, perhaps a few books, and picture reproductions. Fabio Mauroner bought his easels and “a few studio oddments.” Before Modigliani left he told Mauroner that his mother had visited him. Curiously, she came to him, rather than the reverse. Was this a last-ditch effort to get him to come home with her? We shall never know. She did, in any event, give him some money for the trip. She also presented him with a handsome edition of a poem by Oscar Wilde, “The Ballad of Reading Gaol,” which had been published seven years before, in 1898, and became a best seller in France and England.

Since this was a family that set a very high value on poetry, a work by the English dramatist, novelist, and poet, who was tried and convicted in 1895 for his homosexual relationship with Lord Alfred Douglas, and spent time in prison, was certainly not a chance gift but meant to send a message. That much seems likely, even if the message is not so easy to discern.

The poem is an ostensible account of the case of Charles Thomas Wooldridge, a trooper in the Royal Horse Guards who, believing his twenty-three-year-old wife to be unfaithful, slit her throat. He was hanged at Reading Gaol the year Wilde himself faced trial in London. But, as Richard Ellmann points out in his biography, the year 1895 had another significance for Wilde. That year he had rejected Douglas’s article celebrating their love, and a few months later refused to accept Douglas’s dedication of his poems. Ellmann wrote, “The gesture grew out of the feeling that Douglas had destroyed his life … Wooldridge as a real image, and Douglas and himself in parable, all conformed to an unwritten law.” That law, often quoted, was: “For each man kills the thing he loves.”

By another coincidence that presentation of a handsome volume of Wilde’s final work was five years, almost to the month, since the poet had died in Paris. (In November 1900.) It was the same year that Eugénie’s adored brother Amédée had left the world, for whatever reason, the man who never could be happy. Who then had killed whom?

Whatever the unconscious message, this parting gift of a poem by a doomed poet who had, as Ellmann also wrote, “the sense of a strange fatality hanging over him,” was hardly an appropriate message for a son about to set off into life. Was someone “snatching away” yet another of Eugénie’s dear ones, and was she responding in the same way again? Did she think that Amedeo was destroying her life as, by loving him, Wilde felt Douglas had destroyed his? In her diary of 1896, Eugénie wrote, “I am a reflection of other people’s lives.” Did she, at some unaware level, expect his life to become a reflection of hers?

According to Jeanne Modigliani, whose determination to correct a number of false assertions makes her more reliable than most about dates, Modigliani arrived in Paris in January 1906. Springtime in Paris was, after all, the moment of moments. In March 1848 George Sand wrote, “What a dream Paris is, what enthusiasm there is there, and yet what decorum and order! I’ve just come from the city: I flew there and saw the people in their grandeur, sublime, naive and generous … I went many nights without sleep, many days without sitting down. People are mad, they’re intoxicated, they’re happy to sleep in the gutters & congregate in the heavens.” Modigliani was not sleeping in gutters, at least not yet, but comfortably installed in a hotel near the Madeleine. Perhaps he was ready to start work but feeling, as John Dos Passos did a decade later, that the day was “too gorgeously hot and green and white and vigorous.” He continued, “How do people manage to live through the spring? I have never felt it more insanely.”

Modigliani, soon after his arrival in Paris, c. 1906 (image credit 5.2)

Or perhaps, like the American art student Abel Warshawsky two years later (1908), Modigliani arrived one rainy night in the cheerless darkness, loaded his luggage onto one of the newfangled horseless carriages, and was driven along the rain-washed pavements, smelling gasoline mingled with roasting chestnuts, turning and turning into narrower and narrower streets while the driver honked his horn. Warshawsky was arriving in the autumn and perhaps Modigliani did as well. We have no diaries or letters to confirm the month, but Gino Severini, the Futurist painter, states that he arrived in Paris in October 1906, and Modigliani had arrived just three weeks before him. Paris in the autumn has charms of its own, as Dos Passos was to describe, after spending “an atrociously delightful month of wandering through autumn gardens and down grey misty colonaded streets, of poring over bookshops and dining at little tables in back streets, of going to concerts, and riding in squeaky voitures with skeleton horses, of wandering constantly through dimly-seen crowds and peeping in on orgies of drink and women, of vague incomplete adventures—All in a constant sensual drowse at the mellow beauty of the colors & forms of Paris, of old houses overhanging the Seine and damp streets smelling of the dead and old half-forgotten histories.”

The Paris Modigliani found during the Third Republic was a city in dynamic flux, one of boundless opportunity. The ruthless hand of the architect Georges Haussmann had wiped out whole sections of the old city in order to introduce the grands boulevards with their squares and circles that had transformed Paris. Haussmann died in 1891, but his influence continued as more boulevards, such as the Saint-Germain and Henri IV, were built, the Place de la République was reconfigured, the Opéra rose in the middle of its encircling roads, and in the emergence of new parks and handsome apartments. The façades of these were flat and harmonized in the Haussmann style and contained all kinds of miraculous conveniences like bathrooms, running water, gaslights, and central heating. Some 32 million visitors had attended the Exposition of 1889, the Eiffel Tower immediately became the symbol of the new Paris, and just as marvelous was the new underground railway with its sinuous Art Nouveau entrances designed by Hector Guimard. The cafés, the food, clothes, theatres, thés-dansants, opera, concerts, ballet, circuses, the plays, novels, poems, and musical compositions all testified to a new flowering of French genius, a new optimism, and a new prosperity.

Most of all, Paris was a city of art and artists, “apt to strike the newcomer as being but one art studio,” May Alcott Nieriker wrote. “The combination of old and new building, the splendours of the new boulevards and the Bois de Boulogne, the profusion of cafés, the theatres, the contrasting opulence and seediness … the smells of the city … all these aspects … exerted a spell on visitors.” As part of their transforming revolution the Impressionists—Manet, Monet, Caillebotte, Cézanne, Degas, Morisot, Renoir, and Sisley—brought a new sense of daily life, real people in real situations. The year of Modigliani’s arrival Cézanne had just died—of hypothermia, after being caught in a storm at age sixty-seven—painters like Bonnard and Vuillard were developing their theories about flat planes of color, and an even more radical group, Matisse, Derain, Vlaminck, and Rouault, had introduced their own movement at the Salon d’Automne in 1905. Their resulting canvases quickly earned them the name of “Les Fauves”—“Wild Beasts.” Picasso and his Cubistic conundrums were just around the corner.

Thanks to the fame of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, artists from all over the world were drawn to the city’s schools, galleries, museums, and salons. Between 1870 and 1914 the number of artists living in Paris was said to have doubled; it was claimed that “there were more artists per square metre than in any location in the world.” Warshawsky, picking up the latest thinking from his fellow students, was told that Monet and his school had ruined all sense of form in their single-minded pursuit of the effects of light, or so it was claimed. Before he left New York Warshawsky believed that the work of Robert Henri was the very last word in daring and avant-garde insights; in Paris, poor Henri could not even find a gallery prepared to show his work, and he had been rejected by the latest Salon d’Automne.

Scene outside the Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt soon after Modigliani arrived in Paris in 1906: a contemporary postcard (image credit 5.3)

The Bois de Boulogne in 1905: a postcard (image credit 5.4)

Even more than it is today, the life Modigliani found on his arrival was the life of the streets. Influenced as we are by the albumen prints of Eugène Atget made at the turn of the twentieth century to think of Paris in almost Surrealistic terms as a city full of deserted quais, empty chairs in the Tuileries, wet, winding cobblestone streets, and shuttered windows, the impression is deceptive. For the fact was that Atget made his living selling pictures of old Paris to artists and therefore set up his tripod and cameras before dawn, when nothing was stirring. Even so, somewhere in Paris someone was always awake. Anywhere near Les Halles the streets would be reverberating with the early sounds of delivery carts being hauled over the old stones, the shouts of drivers, the whinnying and snorting of the horses, the throngs of predawn buyers and sellers, and the groans of the porters, men who had proved their strength by carrying a wicker basket laden with two hundred kilos of cast iron for a distance of 250 meters. Only they had the right to unload but, on the other hand, they could get help from day laborers, called “coups de main,” who swarmed to Les Halles looking for work.

There were daily deliveries that would surprise today’s city dweller, trained to forage for himself. First came the milkmen, well-built young men in blouses and tall caps with their milk cans, rattling along in their two-wheeled carts at four in the morning. Their appearance was the signal for street sweepers, men and women with highly desirable salaries of three francs a day, to arrive and begin raising their clouds of dust.

At five o’clock small, sturdy women from the boulangeries in aprons and leg-of-mutton sleeves would begin their day by removing dozens of newly baked loaves of bread from the oven and loading them into covered delivery carts. Each loaf was hand-delivered to the door of every apartment, meaning that, in the course of a single morning, the women might be climbing some eighty flights of stairs. Then there were the lady newspaper sellers who received the morning’s news in great sheets, to be assembled into individual copies and neatly folded before they could be distributed by cyclists all over the neighborhood.

As dawn broke, armies of workers filled the streets: the locksmiths in blue smocks, masons in white aprons, flower makers, metal burnishers, knife grinders, glaziers, fishmongers, the peddlers of old clothes and rabbit skins, the organ grinders and sellers of lampshades and umbrellas in their shabby coats and fedoras. There were legions of girls, usually in from the country, working that humble trade immortalized by Mimi in La Bohème. At the bottom of the heap were the “petites-mains,” young recruits who ran errands for the couturiers. Then came the dressmakers and milliners and, ascending the social scale, the typists working in banks and offices. Such sartorial niceties between the working classes animate The Colour of Paris, an illustrated historic and social guide published by the Académiciens Goncourt in 1924. The theme, what it was like to be young and hungry, underlies this account. “What can they do … to earn a living—that is, literally to escape dying of want?” the authors ask. “They are thankful to accept any kind of work. Some of them turn bagottiers, the name given to the poor wretches who run after cabs at the railway-stations in the hope of being allowed to lend a hand unloading the luggage, and who usually spend their breath for nothing; others cry the morning papers, which are distributed among them at the Croissant, at the rate of two francs fifty the hundred. Advertising agents hire some of them as sandwich-men … to announce new wares, and at such jobs they average thirty sous a day.” As for those pariahs of the needle, the makers of underclothing, if they were lucky enough to find any work at all, they earned one franc twenty-five centimes a day, that is to say, ten or twelve centimes an hour. Such were the harsh realities of being down and out in early-twentieth-century Paris.

We may imagine Modigliani sauntering out of his comfortable hotel near the Madeleine, “poured into his clothes, with plenty of cuff on display,” as the poet Blaise Cendrars described him, strolling down the grands boulevards, humming and talking to himself occasionally, as André Breton did: “Toutes les rues sont des affluents / Quand on aime ce fleuve ou coule tout le sang de Paris.”

He had signed up for classes at the Académie Colarossi in the rue de la Grande Chaumière, that street that would figure largely in the sad drama of his short life. The Colarossi, believed to be the oldest art school in the Quartier Latin, had attracted such pupils as Rodin, Whistler, and Gauguin and was favored by Ortiz de Zárate, who no doubt recommended it to Modigliani. Instruction was available, but most artists went there for the chance to draw from a model for a small fee. Marevna, a Russian artist who arrived in Paris in 1912, said the rooms were usually packed. Some of the models, usually Italians of all ages, were clothed, looking “out of their element in the chilly fog of Paris, most as though they had just disembarked from a voyage from Naples,” she wrote. Other rooms had nude models, so these tended to be overheated and stifling; “the model perspired heavily under the electric light, looking at times like a swimmer coming out of the sea. It was like an inferno, rank with the smells of perspiring bodies, scent and fresh paint, damp waterproofs [raincoats] and dirty feet, tobacco from cigarettes and pipes, but the industry with which we all worked had to be seen to be believed.”

Other artists enrolled in the Académie Julian on the rue du Dragon, popular with Americans who could not meet the entrance requirements at the École des Beaux-Arts. After the future muralist George Biddle graduated from Harvard Law School in 1911 he went straight to art lessons at the Académie Julian. He wrote,

The school was in an enormous hangar, a cold, filthy, uninviting firetrap. The walls were plastered from floor to ceiling with the prize-winning academies, in oil or charcoal, of the past thirty or forty years. The atmosphere of the place had changed little since the days of Delacroix, Ingres or David. Three nude girls were posing downstairs. The acrid smell of their bodies and the smell of the students mingled with that of turpentine and oil paint in the overheated, tobacco-laden air. The students grouped their stools and low easels close about the models’ feet. While they worked there was a pandemonium of songs, catcalls, whistling and recitations of a highly salacious and bawdy nature.

In common with students from the Sorbonne, struggling artists, called “rapins,” wore Bohemian costumes of wide-brimmed felt hats or berets, cloaks, and peg-topped trousers. Art was in an uproar. Everyone was looking for the next style, but no one was quite sure which one would become the rage. “Between the pitiless iconoclasts and the defenders of the old order there was a small band of artists who tried to find a line of compromise,” Warshawsky wrote.

One of their favorite devices was to paint a blue line around everything and it was strange to see how even a very academic painting could snap up with this blue outline.

But the younger element, in their mania to emphasize form, set out to deliberately distort it. Horrible monsters, with arms and legs in the last stage of elephantiasis, colored in crude green, violet or scarlet, were painted from slim, delicate, ivory-tinted models. Agonizing landscapes with writhing, reeling forms, as if afflicted with the dance of St. Vitus, were hailed by critics as symphonies of rhythm and plastic design. Totems and idols of jungle Africa were studied and imitated.

Meantime Modigliani was at work. In those days he was painting very small portraits on rough canvas or smooth card with thin colors, Ludwig Meidner recalled.

The results, which recalled somewhat Toulouse-Lautrec or, in their gray-green tones, Whistler’s works, were markedly different from the pictures of the Fauves, which could be viewed at the exhibitions of the Indépendants. They had style and, compared to the latter, were measured and refined in both color and draftsmanship. In order to give these pictures depth and transparency Modi covered them when they were dry with colored varnish, to such an extent that some pictures were covered with ten coats of varnish and, with their transparent golden appearance, recalled the Old Masters.

He had produced enough of these early portraits to have three of them on display in December of 1906 at Laura Wylda’s art gallery at the corner of the rue des Saints-Pères and the boulevard Saint-Germain. In his autobiography, Pane e luna, the artist Anselmo Bucci wrote that they were hallucinatory portraits of women with bloodless faces in a limited, almost monochromatic palette of reddish browns. None of them sold. Modigliani painted two portraits of Meidner and eventually exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants but, his sitter remarked drily, “they went largely unnoticed.”

Modigliani was drawing continually, one of his sitters being Mado, a blond washerwoman who had been one of Picasso’s models. Meidner was intrigued by Modigliani’s practical and inventive approach to drawing. “He drew from life on thin paper, but before it was finished he placed another white sheet beneath it and a piece of graphite paper between the two; then he traced the drawing, greatly simplifying the lines … Whereas in later years he developed his own style of painting, his drawing remained essentially unchanged. Once he set to it, he could produce dozens of portraits in this way.”

Bucci was intrigued enough by Modigliani’s painting in Laura Wylda’s window to go looking for their author and found him at the Hotel Bouscarat in Montmartre. Bucci was accompanied by a couple of friends, and Modigliani responded at once, hurtling down a steep staircase. “Here was a young man wearing a cyclist’s red sweater, small, gay and smiling, with a splendid set of teeth and a mop of curly hair,” Bucci wrote. The first thing Modigliani wanted to know was, were they all Italian painters? Bucci was already mentally cataloging his looks: “Young Jews often have classically shaped, even Roman heads; this was the head of Antinous”—a reference to a youth of such beauty and grace he became a favorite of the Roman Emperor Hadrian’s and was later deified.

The three men started arguing almost at once. There was not a single decent painter in Italy, Modigliani said, with the exception of Oscar Ghiglia. As for France there was Matisse, Picasso, and, Modigliani almost said, “There is me,” but did not quite. Bucci used to meet him at the Café Vachette, where they went to get warm, listen to jazz, and draw. Modigliani drew all the time and would study Bucci’s folio with a seriousness and attention that the artist had seldom received from anyone. They were almost friends, but not quite, perhaps unconsciously competitive. “There was always between us a certain smile, typically Livornese, that was icy cold.”

Modigliani had, of course, visited all the museums and an exhibition of the Fauves at the Salon d’Automne, where he was greatly impressed by the works of Gauguin. But, Ludwig Meidner wrote, “Modi was also interested in Whistler and his fine grey tones, even though the painter was no longer in the public eye. He also admired Ensor and Munch, who were almost unknown in Paris, and of the younger artists he preferred Picasso, Matisse, Rouault and some of the young Hungarian Expressionists who were just coming into fashion.”

His friends were, for the most part, those artists he had already met in Florence and Venice. Besides Bucci, one of his new friends was Gino Severini, who met him by chance outside the Moulin de la Galette. Severini recalls that Modigliani’s search for style was as unsatisfactory as anyone else’s. “Naturally, our conversations centred on the artistic preoccupations of the period,” Severini wrote. “Impressionism no longer satisfied [us]; Picasso was too much of an intellectual … all this gave rise to much discussion. Modi never agreed with anyone. And in particular, he didn’t agree with Futurism. Futurism was based on color relationships, on a certain impressionism. Modigliani didn’t give a damn about all that. He was interested in the Genovese primitives, in Negro art, in the Venetians.”

By the early winter of 1906 Modigliani had moved from the Madeleine to the Bouscarat, at the very center of the artists’ quarter, the Place du Tertre in Montmartre. He rented a separate studio nearby at 7 Place Jean-Baptiste Clément. Several people remembered that studio, Severini among them. He wrote, “From the rue Lepic you could see a sort of greenhouse or glass cage on the top of a wall at the end of a garden. It was a small studio, but very pleasant. The two sides that were glazed meant that it could serve equally as a greenhouse or a studio without being precisely either. Anyway, Modigliani had arrived in Paris with a little more money than me, so he had been able to set up this small establishment, not very comfortable but adequate. He was not at all satisfied with it himself, though, and to tell the truth I liked my own sixth floor better.”

The description, harmless as it is, makes one wonder how one can believe anything that has been written about Modigliani. This was a dwelling that others describe as lacking a single redeeming feature except, perhaps, for a cherry tree in the rue Lepic that one could see from a window. The studio was in the Maquis, a warren of back streets off the main square, of the kind described by Émile Zola in L’Argent, “wretched huts made of earth, old boards, and used zinc, like so many heaps of debris arrayed around an inner courtyard.” Rag and bone men lived there along with dealers in used furniture, foundry workers, and artists, who had moved in en masse, given the rock-bottom rents, and if only temporarily, since the slums were being cleared for new apartment buildings.

André Warnod described the Maquis as “a vast space covered with sheds made from recovered materials, scrap ends of wood, old planks, metal gratings and tinplate, all of it looking ready to collapse at a single push.” Summer would place a merciful blanket over the piles of rubbish with scrub, weeds, a few wildflowers, and the distant cherry tree. There Modigliani lived with a few humble possessions. Louis Latourette, a poet and financial journalist, described the interior. “The shanty was in a state of wild disorder. The walls were covered with sketches, a few canvases lay on the floor, and in the corners were several sculptures. The furniture consisted of a couple of rush-bottom chairs—one with its back broken—a makeshift bed, a trunk used as a seat, and a tin basin and jug in one corner.” Similarly Meidner described Modigliani’s studio as “a tumbledown shack on a treeless, ugly scrap of ground, and although it was furnished in the most spartan manner, oppressive and neglected like a beggar’s hovel, one was always glad to go there for one found an artistic atmosphere in which one was never bored.” His host painted the cherry tree, one of the famous lost paintings. Supposedly Modigliani took it with him when he set off on his endless search for temporary quarters, and at some point it disappeared.

What Meidner remembered best were so many evenings that winter when they used to meet in a dark Bohemian café on the Butte Montmartre called the Lapin Agile. “For four sous you could sit there with a cup of strong coffee and engage in heated discussions about art until dawn. As day broke we would go home through the narrow lanes.” This, for Meidner, was the crowning glory of life in Paris. He would, he wrote, never experience anything like it again.