La Vie de Bohème

Mon Dieu, mon Dieu, la vie est là,

Simple et tranquille!

—PAUL VERLAINE

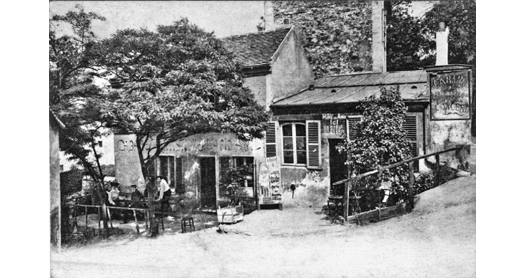

THE LAPIN AGILE, a combination café and watering hole on the steep northern slopes of the Butte Montmartre, played a pivotal role as a meeting place for artists at the start of the twentieth century. At the intersection of the rue Saint-Vincent and the rue des Saules, its origins went back for centuries, and in previous years the rustic cottage that became a tavern had appealed to the Bohemian students of the Romantic movement. With its outdoor terrace, its fresh air, its superb views over the city, and its historic associations, the louche charms of the café, once called Les Assassins, seemed the embodiment of Henri Murger’s Scènes de la vie de Bohème.

By 1903 the café was in danger of being demolished to make way for speculative development. Aristide Bruant, the cabaret singer whom Toulouse-Lautrec had immortalized, bought it. Bruant commissioned a comic artist, André Gill, to paint a suitable scene, that of a rabbit wearing a sash, bow tie, and porkpie hat, balancing a wine bottle, and jumping out of a frying pan. That was the “Lapin à Gill,” Gill’s rabbit, which soon became the “Lapin Agile,” a name that suited it just as well. Bruant knew everybody and quite soon everybody arrived. Along with the small-time criminals who had frequented Les Assassins, there were poets like Guillaume Apollinaire and Max Jacob, writers like Francis Carco and André Salmon, and, most of all, artists: Picasso, Braque, Derain, Vlaminck, Valadon, Utrillo, Gris, and so many others. With his usual perspicacity Modigliani at once attached himself to the list.

Cabaret du Lapin Agile (image credit 6.1)

Returning years later, Carco would discover that not much had changed. “Here behind the wall of the old Calvary graveyard are the big trees, whose leaves in autumn covered the illustrious slabs and fell into our glasses. Here are the innumerable lights of Paris and the same wind which makes them twinkle as before.”

Recollection had transformed what was a modest dwelling, hardly more than a single large room with a low ceiling, some long rough tables, and wooden chairs, into a magical space. The Lapin Agile would become part of the “true” Montmartre before the tourists arrived, where the meaning of art was earnestly debated, where poems were recited, songs were sung, and the last guests left at dawn. Carco wrote, “And indeed, under the lamps veiled with red silk handkerchiefs,…where Frédéric sang, who did not feel as if drugged with some powerful opiate? No dream nor pleasure even approaches that sensation … A very special sort of intoxication, mixed with fancies and depression, uncertain and voiceless … It really rained on those nights, while the drunkest lay stretched upon the benches and innocent white mice, friendly yet cautious, trotted along the mantelpiece.”

Part of the allure was provided by the proprietor, Frédéric Gérard, known as Frédé, a man of unsuspected talents who began on the street selling fish before scraping together enough money to buy a small cabaret and then the Lapin Agile. Frédé had an unkempt beard, straggling hair shoved under a fur hat, a sweater, and boots, and was essentially a cabaret artist. Le Zut, his previous nightspot, had been frequented by the young Picasso, who had helped whitewash the walls. One night after several sangrias Picasso had painted a mural, the Temptation of St. Anthony. When Frédé set himself up in a new location, Picasso came with him. Frédé would play and sing, his daughter would pass the hat, and bit by bit the walls would fill up with paintings, the accepted unit of exchange for artists down on their luck. Picasso contributed Arlequin et sa compagne, there were some early Utrillos, drawings by Steinlen, a statue of Apollo Musagetes, a Hindu God, and a gritty anonymous sculpture of Christ on the cross that everyone autographed. Frédé was the soul of good humor, greeted each arrival by name, and would invariably wish his regulars a good digestion. This, Philippe Jullian quipped, they needed in order to “swallow his special cocktail, a mixture of Pernod and grenadine.”

Nina Hamnett, the English sculptor, recalled that they drank kirsch with small plums inside and, although she conceded Frédé played a fine guitar, was one of those who did not warm to him and always ended up in an argument whenever she went to the Lapin Agile. It would seem that the portrait of Frédé, as fondly delineated, has been extensively retouched.

“The picture of ‘le brave Frédé’ that emerges from the more nostalgic memoirs of the period—singing his famous repertory of street songs, playing the cello, clarinet and guitar by ear … baking pottery in his kiln, helping his Burgundian wife … serve up appetizing dinners (wine included) for two francs a head and being a supportive father-figure to one and all—is too good to be true,” John Richardson wrote. “ ‘Frédé was a ruffian,’ Picasso said.” And if Frédé one day succumbed to the lure of tourism and selling cheap souvenirs, he had at least given the artists of Montmartre some unforgettable memories. Part of the café’s charm, Carco continued, “came from the surroundings of confused bric-à-brac, from the obscene mouldings, from the immense plaster Christ, from Picasso’s canvases, Utrillo’s, Girieud’s … And Frédéric with his guitar … the dampness of the walls, the hidden despair of us all, our poverty, our youth, wasted time, completed the atmosphere.”

A typical evening at the Lapin Agile (image credit 6.2)

Modigliani, making himself a part of the new crowd with ease, had the rare gift of being perfectly delighted in any company. One sees this in a series of candid camera photographs taken by Cocteau during World War I and published by Billy Klüver and Julie Martin in Kiki’s Paris. Modigliani is all eager attentiveness as Picasso explains a joke to André Salmon to which, no doubt, he is about to add an irresistible coda. This ability to make friends was a consequence, perhaps, of having grown up in his mother’s “smala,” when one never knew which relative or dear friend might be sitting down to dinner with the family or have arrived for an indefinite stay. Modigliani is the subject of so many accounts, as he meets a friend by chance, or appears at a sidewalk table, or invites a third to his studio and a fourth to a musicale, that one believes he was seldom alone.

Meidner wrote, “At this time he was not … the gloomy, cynical and sarcastic person his biographer [Arthur] Pfannstiel describes, but rather lively and enthusiastic, always sparkling, full of imagination, wit and contradictory moods … I was overwhelmed by his open attitude towards everything, in particular whenever he spoke about beauty. Never before had I heard an artist speak with such ardor.”

The writer Ilya Ehrenburg thought his work showed “a rare combination of childlikeness and wisdom. When I say ‘childlike’ I do not, of course, mean infantilism, a native lack of ability or a deliberate primitivism: by childlikeness I mean freshness of perception, immediacy, inner purity.” “I can see Modigliani now,” Maurice de Vlaminck wrote in 1925, five years after his death, “sitting at a table in the Café de la Rotonde. I can see his pure Roman profile, his look of authority; I can also see his fine hands, aristocratic hands with sensitive fingers—intelligent hands, unhesitatingly outlining a drawing with a single stroke.” Gino Severini said, “He did not need stimulants to be brilliant, alive and full of interest every moment of his life. Everyone loved Modigliani.”

In those days artists were expected not only to dress distinctively—hence the uniform of “les rapins,” with their corduroy trousers and capes—but set the fashion. Picasso inspired a rash of early imitators with his pair of faded and patched blue overalls, red-and-white-dotted cotton shirt, espadrilles, and cap. Quite soon after arriving in Paris Modigliani seems to have abandoned his expensively correct clothes for something more appropriate. He chose a suit of chocolate-brown corduroy with a matching vest, an open-necked shirt, and a red kerchief. It was, in fact, an outfit that harked back half a century, since the sculptor Auguste Clesinger (1814–1883), who was photographed by Nadar in 1860, was wearing the identical outfit.

Roger Wild described the effect as somewhat careless but with calculated intent. There was the suit of faded velvet, the shirt of blue and white check, “the only one he owned but that he washed out every night, and a tie that was always awry. He would have found it shocking, it seems, to wear a tie on straight like the rest of the world.” Still there was something about him, an eclectic kind of style setting, according to a friend quoted in Artist Quarter. “He was the first man in Paris to wear a shirt made of cretonne … He had colour harmonies that were all his own.” Picasso did not hide his admiration for Modigliani’s sartorial style. “There’s only one man in Paris who knows how to dress and that is Modigliani.” Abdul Wahab, another artist in Modigliani’s circle, recalls that Picasso and his friends were seated at a sidewalk café when they saw Modigliani approaching. He was with a friend not known for his sartorial attention to detail. Picasso said, “Look at the difference between a gentleman and a parvenu.” He was, Jean Cocteau wrote, “our aristocrat.”

The “true Montmartre” in which Modigliani found himself in 1906 was still, in all essential respects, a village. It was one that Haussmann’s zeal to obliterate had spared, and was being minutely documented by Eugène Atget at a moment when the buildings were in a picturesque state of decay, old windmills still dotted the landscape, its slopes were still covered with grape vines and vegetables, and nights were absolutely silent. By the time Modigliani arrived anyone who was anyone, with the exception of Vlaminck and Pierre Matisse, was already living there. Marcel Duchamp, Jean Renoir, and Théophile Alexandre Steinlen lived on the rue Caulaincourt. Edgar Degas was on the rue de Laval, Pierre Bonnard on the rue de Douai, André Derain on the rue de Tourlaque, Marie Laurencin on the rue Léonie, Georges Braque on the rue d’Orsel, and Francis Picabia on the rue Hégésippe Moreau. Picasso, Kees van Dongen, and Juan Gris were living in the Bateau Lavoir. This squalid tenement began life as a piano factory and, later, a locksmith’s workshop, before being turned into artists’ quarters in 1889. The Bateau Lavoir was, presumably, so-called after the laundry boats moored along the Seine that always smelled of wet, dirty clothes. Philippe Jullian wrote, “[T]he huge building, with walls made of brick and timber pierced by enormous windows, was on four floors built against the side of the Butte, facing a narrow courtyard flanked on its other side by a blackened retaining wall.” Richardson, Picasso’s biographer, observed, “The place was so jerry-built that the walls oozed moisture … hence a prevailing smell of mildew, cat piss and drains … On a basement landing was the one and only toilet, a dark and filthy hole with an unlockable door … and next to it, the one and only tap.” But the rent was cheap—only fifteen francs a month, compared to one franc a night for the most modest hotel, and Picasso moved in. Later, so would Modigliani.

The Bateau Lavoir, Montmartre (image credit 6.3)

The rue des Saules, Montmartre (image credit 6.4)

Most of the young and aspiring tenants of the Bateau Lavoir were inured by conditions which, in the days before plumbing and central heating, were common, even in middle-class habitations. What counted most was seeing and being seen, within walking distance of those impromptu meeting places and vital centers of warmth, the Chats Noirs and Lapins Agiles of the shifting moment. Besides, despite the builders, Montmartre was still a village, albeit an ancient one, inhabited since pre-Roman times. After the Romans moved in they erected temples to their gods. In the Middle Ages abbeys were built there, including windmills that were ecclesiastical property, and it was probably then that the Mont des Martyrs, or Hill of Martyrs, acquired its name. Montmartre also became associated with the underworld as a consequence of the gypsum quarries that had been worked since the sixteenth century. By the nineteenth the hillsides were riddled with labyrinths, an ideal refuge for rogues and vagabonds. On the outskirts of Paris, but a part of it: Montmartre was the refuge of nonconformists and rebels, the indigent, the working poor, and all the other untouchables.

After 1860 when the commune of Montmartre became incorporated into Paris, a raffish bunch of musicians, painters, and poets arrived, attracted by the light and the cheap rents. “It was in Montmartre that the cult of the artist, the artistic manner evolved from the writings of Baudelaire, developed,” Jullian wrote. “The artist had none of the preciosity of the Anglo-Saxon aesthete; he had a taste for Beauty certainly, but he was free to find that beauty in scenes of misery and among the dregs of humanity.” Of course, they all knew each other. “Montmartre was, above all else, a society of friends; everyone was in and out of each other’s houses all the time and the girls [models] went from one studio to another.”

The exact moment at which Modigliani left his hotel, the Bouscarat on the Place du Tertre, and moved into his shed in the Maquis, has not been recorded, although it must have happened sometime in 1907. André Utter, an amateur painter who married Utrillo’s mother, Suzanne Valadon, met Modigliani one day by chance. He was outside painting a street scene when Modigliani walked up to him and started talking. In the course of the conversation Modigliani said he had just returned from London, which would put the probable date as late in 1907, and even claimed to have exhibited with the Pre-Raphaelites.

It appeared that Modigliani was penniless and his bill at the hotel weeks or months in arrears. The proprietor was holding his paintings as security, and Modigliani did not know what to do. In short, his days as a young man of means were ending. It is repeatedly asserted that Modigliani was a spendthrift. Although so many claims about his behavior are suspect, this one rings true, if only because of his family’s history and the Garsin predilection for taking advantage of good times and drowning in debt in lean ones. Breeding, bearing, seigneurial largesse—these were the lessons they had imparted. Prudence was not one of them. So Amedeo spent with a free hand and endured when he did not. On the other hand, times of want called for ingenuity and planning, in which he was also schooled. An early lesson arrived fortuitously at the Bouscarat. One night the ceiling plaster of his room fell on his bed with a crash. He was unhurt. But Modigliani, at his most ingenious and inventive at such moments, talked about head injuries and the prospect of lawsuits. The proprietor said, “Oh get to hell out of it and take your rotten junk with you.” This wonderful piece of luck never happened again, but it gave Modigliani an idea.

It seems that Modigliani was never actually destitute since Eugénie and Mené contributed a small stipend. Even so he often went hungry. To have reached the limit of one’s resources was described in 1903 by James Joyce. He wrote from Paris: “Dear Mother, Your order for 3s 4d of Tuesday last was very welcome as I had been without food for 42 hours. Today I am twenty hours without food. But these spells of fasting are common with me now and when I get your money I am so damnably hungry that I eat a fortune (1/-) before you could say knife … If I had money I could buy a little oil stove (I have a lamp) and cook macaroni for myself with bread when I am hard beat.” Joyce’s attempt to find fame and fortune in Paris ended when, two months later, he returned to Ireland for his mother’s funeral.

Before he became well known, Carco knew more tricks than Joyce did on how to survive in Paris. For instance, L’Intransigeant was the preferred newspaper for stuffing mattresses because it had six more pages than the other dailies. As for breakfast, the trick was to creep into buildings just after the morning milk and rolls had been delivered but before the owners were awake. Finding lunch and dinner was harder even if you were prepared to root around in the gutters of Les Halles after the morning’s market. On the other hand, food was cheap, and three francs a day, the wage paid to municipal street sweepers, was a fortune. Carco wrote, “In the Rue de la Montagne Sainte-Geneviève, where … I … was learning to set type and print books … meals cost twelve sous. Bread, ten centimes; meat, thirty centimes; vegetables, fifteen; hot chocolate, one sou, so that from three francs there was enough left for luxury.” Nevertheless the cheapest meal costs too much when you have no money. Modigliani had a solution for that.

The uncharming Rosalie Tobia enters the story at this point. She had posed in the nude for Bouguereau, Carolus Durand, and Cabanel and had lovers. At that stage it was impossible to imagine since she was completely shapeless, with sagging breasts, a dirty dress, and some sort of net or Neapolitan kerchief covering her stringy hair. Rosalie was owner of a tiny restaurant, Chez Rosalie, on the rue Campagne Première, narrow, smoky, and dimly lit, reeking of boiled cabbage, which she ran with her son Luigi. While she stirred the soup with a wooden ladle, Luigi, in shirt sleeves and wrapped in a blue apron, would be drying glasses and dishes with a filthy rag.

Chez Rosalie advertised itself as a crémerie, serving café au lait and chocolate, but was, in effect, a kind of personal charity. Rosalie would trudge to Les Halles before dawn each morning to buy the day’s provisions, returning on the Métro with a sack on her back. She had a quick temper, one that concealed a warm heart. Any stray dog or cat at the door was sure of a meal. She also fed mice and the rats in nearby stables, to the exasperation of her neighbors. Starving artists were another specialty. She would assemble a group at one of her four marble-topped tables, disappear into her minute kitchen, and appear with an enormous bowl of steaming spaghetti, then bang it down in the middle of the table. There would be cheap wine and few leftovers. Those who could pay, did. Those who could not, ate anyway.

Lunia Czechowska, who knew Modigliani in the last years of his life, explained that Rosalie had her protégés but Modigliani was in a category all his own, “her god.” He liked the Italian dishes she favored with plenty of oil and would say, “When I eat an oily dish it’s like kissing the mouth of a woman I love.” If he had nowhere to stay he would bed down on sacks in the back and, on good days, help Rosalie peel the potatoes and string the beans. On bad days, she would try to get him to pay his bill and he would reply, “A man who has no money shouldn’t die of hunger.” That would start a fight. “Dishes and glasses would be thrown and sometimes Modigliani would rip his drawings off the wall,” Martin and Klüver wrote. According to Czechowska, Modigliani’s solution would be to start talking in French, which Rosalie barely spoke, and that would end the matter.

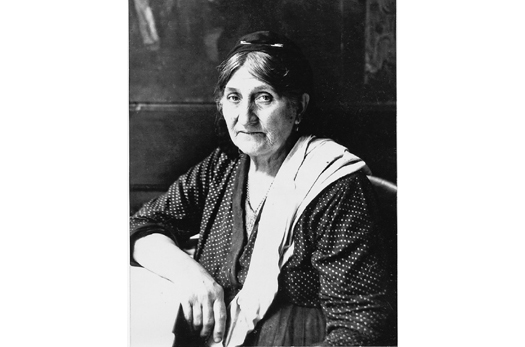

Chez Rosalie, where Modigliani could always be sure of getting a meal (image credit 6.5)

Payment was simple: another drawing, Rosalie complaining all the time that she had too many already. The legend, probably true, is that she kept them, covered with grease, in a kitchen cupboard, the rats gnawed away at them, and when she thought of cashing them in it was too late. But then, art appreciation was hardly Rosalie’s strong point, despite the Modiglianis, Kislings, Picassos, Utrillos, and the like on the yellow-stained walls. Marevna tells the story that, to atone for some of those free meals, Modigliani once painted a fresco on one of her walls. Rosalie was so disgusted that, next day, she made Luigi cover it up with white paint.

Rosalie (image credit 6.6)

Modigliani’s descent from comparative wealth into want, like that of his parents some twenty years before, was enough for friends to notice but an indignity he endured in silence. Meidner wrote, “Modigliani seemed to be in the direst of financial straits. I often heard him barter with his acquaintances on this account, but we never discussed money. Although I was not badly off at this time Modigliani never addressed such requests to me—I don’t know why. He was very proud in this respect. A year later, when his plight was quite desperate, he would absent himself for days on end in order to find some money, either by selling his drawings or by selling the works of another artist to a dealer.” Perhaps some artist’s model would take pity on him and stand him a drink or dinner. In the meantime he lived where he could for as long as he could, choosing the right psychological moment to disappear into the night. He would surface in a new quarter, with a new landlord, a new address, and a fresh neighborhood of restaurants where he could run up more bills. Researchers are still trying to list all his addresses and puzzle out the reason why he moved so often, which would have given him a laugh.

Louis Latourette provides an invaluable insight into the life of the young man with whom he strolled the boulevards in 1906–07. “As we left the restaurant I was astounded to see [that my companion] was carrying a copy of a book by [a philosopher], Le Dantec,” Latourette wrote. “ ‘I adore philosophy,’ he told me. ‘It’s in my blood,’ ” explaining the family legend that put him in a direct line with Spinoza.

“In the course of a long evening walk on the terrace of the Sacré-Coeur, he recited numerous passages from Leopardi, Carducci and above all the Laudi of d’Annunzio, about which he was passionate. Then he launched into an ostentatious discussion of the works of Shelley and Wilde.” (This, it should be noted, was a conversation with a poet.) “There wasn’t a single word about painting,” Latourette said.

Another friend, Roberto Rossi, who became a well-known sculptor in Italy, discovered Modigliani’s equal responsiveness to music. Rossi said, “I would often go to the ‘Concerts Rouges’ in the rue de Tournon. You could listen to the program there for 1 franc 25.” One evening soon after his arrival in Paris, he happened to be sitting near Modigliani for a program of the music of Boccherini. “We quickly realized we were from the same country. When Modigliani and I were together we spoke our Italian, flavored with Florentine expressions … Our first conversation was as much about friends we had in common in Florence as it was about the music of Boccherini. I would tell he had a deep sensibility by the way he half-closed his eyes when he spoke about the music.”

Modigliani was sure of his talent but had not yet found a sense of direction. Louis Latourette thought he might even have been disoriented by the multiple possibilities. When the poet went to visit the painter, the studio was in chaos, its walls covered with canvases, its floors littered with paper, and boxes overflowing with drawings. Modigliani’s mood was despairing: he was going to throw everything out. Perhaps it was the fault of his Italian eye; he could not get used to the subtle watercolor light of Paris. “You can’t imagine how many times I’ve started again with themes in violet, orange and deep ochre.” Max Jacob, a poet and writer who was also an artist, understood why Modigliani was struggling. What he was seeking was perfection itself. He wrote, “Everything in Dedo tended towards purity in art … a need for crystalline purity, a trueness to himself in life as in art…[T]hat was very characteristic of the period, which talked of nothing but purity in art and strove for nothing else.”

Among the litter was a piece of sculpture, the torso of a young girl; it reminded Latourette of an actress who used to recite Rollinat’s verses at the Lapin Agile. Modigliani treated it with scorn. “It’s nothing! Imitation Picasso, a wash-out. Picasso would kick this monstrosity to pieces.” But a few days later, when Modigliani announced that he had destroyed almost everything except for a few drawings, Latourette noted that the sculpture had been saved. Modigliani was half thinking of giving up painting and going back to sculpture. Curiously enough, the young Henri Gaudier-Brzeska was coming to the same conclusion at about the same moment. “Painting is too complicated with its oils and its pigments, and is too easily destroyed,” he wrote to a friend. “What is more, I love the sense of creation, the ample voluptuousness of kneading the material and bringing forth life, a joy which I never found in painting; for, as you have seen, I don’t know how to manipulate colour, and as I’ve always said, I’m not a painter, but a sculptor…[S]culpture is the art of expressing the reality of ideas in the most palpable form.”

Unlike Gaudier-Brzeska, Modigliani did not work from clay but directly from stone in the Italian style. Still, one may assume he shared similar sentiments. He wanted sculptural density and weight, he wanted roundness and monumentality, the exhilaration of creation and the feeling of the stone against his hand. He had begun experimenting again in that direction, his invariable plan being to court the masons working on new buildings over a bottle of wine and then make off with a block of stone. He was not yet ready to concentrate on sculpture alone; that would take another two or three years. Meantime he began to refine his already formidable techniques for eating without paying.

Gino Severini, the Futurist painter, recalled that he was having dinner one evening in a Montmartre café when Modigliani appeared, sans le sou and looking very hungry. Severini invited him to join him, and Modigliani ordered a meal. Severini, however, had no money either and was eating on credit. As the end of the meal approached Severini became more and more anxious. What was he to do? Modigliani knew him well enough to know that, once under the influence, Severini would collapse with laughter. So Modigliani quietly slipped him a small amount of hashish. It was an instant success. When the bill was presented Severini immediately saw the funny side. He smirked, he giggled, he let out a belly laugh. It really was a joke. It was a riot. He cried with laughter. He was doubled up. He almost rolled on the floor. Evidence that he made a total spectacle of himself was not long in coming; the owner threw them both out.

At that moment Modigliani was exhibiting, trying to sell his work, and looking for a dealer. No longer was the Salon, that fortress of the artistic establishment, the only place an artist could exhibit, or even the Salon des Réfusés, established by the Impressionists in the 1860s. Now there was the Salon des Indépendants, established by such artists as Georges Seurat, Odilon Redon, and Paul Signac. And there was yet another anti-establishment venue, the Salon d’Automne. The creation of a prominent architect and writer, Fritz Jourdain, the Salon d’Automne attracted a socially prominent crowd when it opened its doors in October 1903. At the Petit Palais, Proust, in white tie and tails, mingled with the politician Léon Blum and the aristocratic Comtesse de Noailles. It was a success on every count and became at once a major goal of every young unknown. In 1907 the Salon accepted seven works by Modigliani: the portrait of Meidner, a Study of a Head, and five watercolors.

Again, nothing sold. But in this case, it hardly mattered. The event also exhibited forty-eight oils by Cézanne, the master of Aix who had died the year before. His watercolors were concurrently on view at the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune. Modigliani was taken by storm. “Whenever Cézanne’s name was mentioned, a reverent expression would come over Modigliani’s face,” Alfred Werner wrote. “He would, with a slow and secretive gesture, take from his pocket a reproduction of ‘Boy With Red Vest,’ hold it up to his face like a breviary, draw it to his lips and kiss it.” That was the year that Modigliani visited Picasso’s studio in the Bateau Lavoir and saw Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, historically considered the birth of Cubism. The painting of four naked whores in a brothel met with puzzled incomprehension when it was first viewed. Richardson wrote, “Although friends sympathized with his aspirations, none of them was capable of understanding the pictorial form that these aspirations took. When he allowed Salmon, Apollinaire and Jacob to see the painting, they … took refuge in embarrassed silence.” Modigliani admired Picasso without reservation. “How great he is,” he once remarked. “He’s always ten years ahead of the rest of us.”

The fact that, unlike Picasso, who was only three years older, his work was not selling, did not disturb Modigliani, at least not outwardly. After his older brother Umberto, now on an engineer’s salary, sent him some money, Modigliani’s letter of thanks was calm and optimistic. “The Salon d’Automne has been a comparative success and acceptance en bloc, practically speaking, was a rare occurrence since these people form a closed clique,” he wrote. He hoped to exhibit at the Salon des Indépendants in the spring of 1908. “If I give as good an account of myself at the Indépendants I shall certainly have taken a first step forward.”

Noël Alexandre is a middle son, one of eleven children of Dr. Paul Alexandre, who saw Modigliani almost every day in the years leading up to World War I, as friend, confidant, and his first collector. Noël Alexandre is also author of a landmark study, The Unknown Modigliani, Drawings from the Collection of Paul Alexandre, that accompanied an exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1994. The exhibition was in the nature of a revelation since it not only showed some four hundred drawings that had never been exhibited before, but contained previously unknown letters, photographs, an account of Modigliani’s life sent by his mother in 1924, letters from Jean, Paul Alexandre’s brother, Paul Alexandre’s own letters and reminiscences, and a totally fresh view of Modigliani’s personality and the development of his talents.

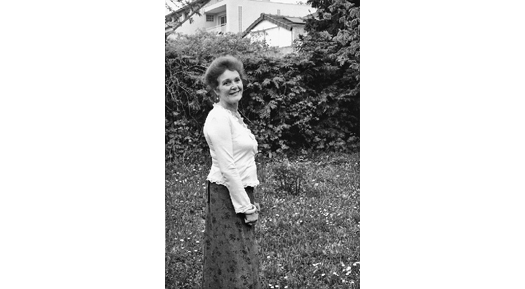

One spring day I was invited for lunch in the country house in suburban Paris owned by Noël Alexandre and his wife, Colette Comoy-Alexandre. We lunched in their light, airy living room, its French windows opening onto a country garden with apple blossoms scenting the air. The lilacs were in bloom and Colette Comoy had placed vases of them ascending the steps of a curving staircase. It was the first of what would become several illuminating encounters in which Noël Alexandre explained that the “legend” of Modigliani had led him to revisit the story from the beginning. These stories were canards, completely at odds with everything he had learned from his father. He was determined to destroy the false image of Modigliani that had been created down through the decades.

Colette Comoy-Alexandre in her country garden, Sceaux, outside Paris (image credit 6.7)

Paul Alexandre, born in 1881, was the son of Jean-Baptiste, a prosperous pharmacist living in an hôtel particulier in Paris that has since become an embassy. (The address then was 13 avenue Malakoff, now avenue Raymond Poincaré.) He and his younger brothers, Pierre and Jean, went to a Jesuit College in the rue de Madrid. Paul became a dermatologist and Jean, a pharmacist like their father. Paul’s interest in art began at an early age. He loved visiting the Louvre, and when his parents decided to redecorate their large living room Paul persuaded them to employ Geo Printemps, a young artist friend of his. Printemps brought someone with him to help, a budding sculptor named Maurice Drouard. Paul and Maurice became fast friends, and the young medical student was embarked on the other passion of his life, art, and artists.

Through Drouard, Paul Alexandre met a whole group of painters and sculptors that included Henri Doucet, Albert Gleizes, Le Fauconnier, and, in particular, the sculptor Constantin Brancusi, who was to play an important role in Modigliani’s life. In those days Paul Alexandre was renting a room in the rue Visconti and sharing it with two brothers of a friend from the Jesuit College, Louis de Saint-Albin. This was fun, if a bit cramped, so they used to meet at a café nearby, Mauguin’s in the rue de Buci, which was famous for its two-centime coffee and usually jammed. Then Paul Alexandre had the idea of renting a private room on the first floor of a nearby restaurant and inviting his friends there once a week. After awhile that was too small as well. Then Paul Alexandre decided to rent a house.

Noël Alexandre, a son of Paul Alexandre, Modigliani’s first patron (image credit 6.8)

Noël Alexandre said, “My parents had the first floor on the avenue Malakoff [American second]. My grandmother was on the second floor. We children had the third floor, and on the fourth, there was an enormous salon with grand pianos at either end where my father’s friends would come to practice for their concerts. It was a liberal atmosphere but still, my father was living with his parents. When one is between twenty and thirty, one wants to be a bit more independent.”

Then, in 1907, Paul Alexandre discovered a pavillon at 7 rue du Delta. Thanks to his collection of photographs, just what the house looked like has been preserved in handsome detail and is revealed as a picturesque two-story semiruin. Its twelve rooms and floor-to-ceiling shuttered windows were oriented toward a plot of wasteland fenced off from the street. The house was owned by the city of Paris and was slated to be demolished. Paul Alexandre pulled some strings and rented it for a trifling sum for the next six years. It evidently represented a retreat and an escape, but it was more than that. Perhaps it was the discovery of just how desperate for money young artists could be that influenced him. The young doctor, gregarious by nature, in love with art and generous in spirit, created a meeting place for artists who came and went, knowing they had a place out of the rain, a bottle of wine, a meal, and somewhere to sleep, even if it was only the floor.

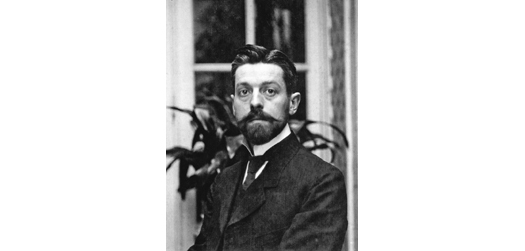

The young doctor Paul Alexandre in 1909 (image credit 6.9)

The first tenants, Drouard and Doucet, stayed on and on, Drou-ard until 1913. They brought Centore and he brought another sculptor, Guiraud Rivière. Gleizes, who fell out with his wealthy parents, arrived accompanied by some expensive-looking furniture. By then Paul Alexandre had started a clinic in a working-class part of Paris five minutes from the house. Even though a dermatologist, he wrote that “I was called out for anything. I used to be astonished at the maturity of the youngsters in this district, who played in the gutters but who, when their parents were ill, knew how to adopt adult language to fetch me and speak to the doctor. Then they would go back to their gutters.” Every moment not spent caring for the sick was devoted to the rue du Delta.

There were “Delta Saturdays” when everyone came. There were chess games and gatherings with plenty of high-minded talk. Little by little the wasteland behind the house was cleared, tables and chairs set out, flowering vines climbed the walls, and there was a stab at a lawn. There were plays, film scenarios, and racy theatricals in which Raymonde, wearing a saucy pair of high boots and nothing else, appeared from behind a curtain at the bidding of Alexandre’s baton. There were “pagan dances” with the sheets from Drouard’s or Alexandre’s bed that Brancusi in particular enjoyed. There were readings of Villon, Mallarmé, Verlaine, and Baudelaire and afterward Alexandre would analyze what it all meant. There were musicales, and each year’s “Quatz’ Arts” costume ball called for months of preparation.

A theatrical evening at the rue du Delta; Paul Alexandre, at right, is master of ceremonies. A study for Modigliani’s The Cellist is on the wall above; from left, Luci and Henri Gazan (on the sofa), and Henri Doucet and his wife (center). The model is known as Raymonde. (image credit 6.10)

There was plenty of wine and there were drugs. The public menace represented by drunkenness was well understood and a law of 1873 made its public display a crime, although it was unevenly enforced. On the other hand, where everyone had wine with a meal, abstinence was unknown. “The consumption of alcohol, an accepted sign of virility, helped create an individual’s image,” Michelle Perrot wrote. As for drugs, Richardson wrote that they were, as now, a way of life. Pharmacies sold ether legally for thirty centimes a dram and its excessive use was known to have hastened the death of one of Picasso’s friends, the playwright Alfred Jarry. Another friend, Max Jacob, was “so addicted to this drug that he was obliged to conceal the smell by burning incense in his Bateau Lavoir studio.”

The ruined, barely habitable, but romantic villa on the rue du Delta where Paul Alexandre housed a small colony of artists, as seen in 1913 (image credit 6.11)

Absinthe, the milky opalescent green liquid known as “La Fée Verte,” was, in particular, a drink so favored by the smart set that the cocktail hour became known as “l’heure verte.” Alfred Jarry, whose play Ubu Roi had made him famous but not rich, also indulged. Sacha Guitry wrote, “He inhabited a miserable, dilapidated hut on the edge of the river. You could still read on the walls the words ‘Cleaning and Mending.’ It had an earthen floor, and a bicycle hung from the roof, ‘to stop the rats from eating the tyres,’ explained the seedy-looking writer, a ‘proud little Breton’ with a droopy moustache and long hair which had a greenish tinge acquired from drinking strange concoctions.” Despite its adherents, including Oscar Wilde, who claimed that absinthe led to wonderful visions, the conviction took hold that “it was believed to damage the brain cells and cause epilepsy,” and it was banned in France in 1914.

No such concerns were raised over the fumeries in Montmartre where one smoked opium; Picasso was a regular visitor. Richardson called Alexandre a “Svengali” for introducing Modigliani to hashish. But this was also legal. “Montmartre, at this time, had become infected by the craze for dope, principally hashish,” Charles Douglas wrote in Artist Quarter. “Everyone took the fashionable drug, even the village lads. Only the apaché element resisted the new temptation. As good businessmen … they realized that if they succumbed it would be bad for trade.”

Marevna, arriving in Paris in 1912, experimented along with everyone else. “We ate the paste in little pellets or mixed it with tobacco and smoked it. The effect on me was usually a desire to laugh, followed by a fit of weeping or chattering about everything I saw (or thought I saw). At first I liked the drug because of the extreme, almost frightening lucidity I gained from it. Then one day I jumped through a window to the roof of the next house, imagining it was just below (it wasn’t). I escaped with only a sore behind.”

Alexandre’s hashish parties began because he knew that the drug, cannabis, extracted from dried hemp, also caused startling visions; he thought that would be marvelous for painters. He had tried it himself. “Late one night, as I walked … all along the Champs-Élysées or the Quai d’Orsay, I could see the gas lamps rise up in tiers like notes of music on an imaginary stave and I began to sing the tune written there. From the Place de la Concorde the rue Gabriel appeared … like a magical vision. The trees, lit from underneath, seemed like the climax of a firework display.”

Modigliani appeared at 7 rue du Delta one day in November, a month after his first appearance in the Salon d’Automne. He had been evicted from the Place Jean-Baptiste Clément and, it would seem, had nowhere to go. A mutual friend, Henri Doucet, brought him to the house to meet Paul Alexandre. Modigliani was accompanied by Maud Abrantes, an elegant, worldly friend who appeared to have transported the entire contents of his studio—clothes, books, and sketchbooks—in her car. Very little is known about her. She was American, married, living in Paris, and cultured, but how they met and their exact relationship is unknown. Modigliani made several studies of her and painted her portrait in grayed-off pastels. Her features, well marked and handsome, are notable for the eyes, which are disproportionately large, and smudged with blotches of paint as if to indicate mute suffering. What is curious about Modigliani’s arrival at the rue du Delta is that, although supposedly homeless, he never took up lodging there and spent that particular night in a hotel on the rue Caulaincourt. Apparently the lady was paying.

Modigliani was looking for studio space, and after finding it nearby he came and went like a member of the household. Paul Alexandre wrote, “Modigliani charmed everybody immediately. He trusted any stranger we might introduce to him, and was completely open, with no pretences, inhibitions or reserve. There was something proud in his attitude and he had a good firm handshake. Modigliani was more than an aristocrat, ‘une noblesse excedée’ [‘surpassingly noble’], to use an expression of Baudelaire’s which fits him perfectly.”

Modigliani became Alexandre’s latest cause. The latter introduced him to everyone and began commissioning portraits. Alexandre wrote, “He already had a deep-rooted confidence in his own worth. He knew that he was an innovator rather than a follower, but he had not as yet received a single commission.” Alexandre’s first project was a portrait of his elegant, reserved father. As was his custom Modigliani made a number of delicate sketches before trusting himself to paint a portrait of Jean-Baptiste Alexandre, seated, in black, with a high collar, in tones of bluish charcoal, grayed-off greens, and pinkish maroons. The old man confronts the viewer with grave distinction, his white beard precisely trimmed to reveal a pink bottom lip, his eyes tired but calm. He has a natural authority and so does his son, who strikingly resembles him. In one of several paintings by Modigliani Paul Alexandre is standing against the same background. His hand is on his hip, there is the same-shaped face, the same steady, unsmiling look, the same air of reserve. There is no hint here of the admirable qualities of both men: a high-minded, idealistic view of life and a spontaneous benevolence. In Paul Alexandre, young as he was, Modigliani had found someone with an eighteenth-century concept of the patron who recognizes, and nurtures, a rara avis. He was twenty-six; Modigliani was twenty-three.

Modigliani’s study in watercolor of Maud Abrantes (image credit 6.12)

They became inseparable. As long as the drawing show of Cézanne’s work was still at Bernheim’s they returned day after day. Alexandre wrote, “I remember an anecdote about his visual memory, which was extraordinary: once, to my great astonishment, he drew from memory and at a single attempt Cézanne’s ‘Boy with a Red Waistcoat.’ ” At Vollard’s gallery in the rue Laffitte they studied a series of Picasso’s Blue Period paintings. At Kahnweiler’s in the rue Vignon Modigliani was transfixed by an unobtrusive watercolor of Picasso’s that, curiously, represented a young fir tree, turning green, encased in blocks of ice. When they went to visit Henri (Le Douanier) Rousseau, who died shortly thereafter (1910), Modigliani drew Alexandre’s attention to one painting, The Wedding (1904–05), in which a family group, transfixed as if posing for a camera, stands expressionless under a bower of trees. Whether assessing Nadelmann’s bronzes or the work of a young unknown, Modigliani gave it the same concentrated study and generous praise. There was “no trace of envy or disparagement,” even if the owners did not return the compliment.

As Picasso’s fir tree in ice would suggest, Modigliani, with his actor’s instincts, was fascinated by the boundary line between fantasy and reality. Unexpected juxtapositions and intense visual sensations interested him in particular. They used to go to the old Gaité-Rochechouart, which had mirrored walls, meaning that, if one sat in the right seats, the performance at center stage would be split into a million tiny reflections. Modigliani was just as dazzled by the circus, which presented so many unexpected possibilities: clowns with gaping mouths, acrobats dangling and twisting from wires, harlequins with grinning faces and, in particular, Columbines, a series of lovely brazen women wearing skirts and not much else. Modigliani was famously dissatisfied with his drawings. Alexandre observed that when an image attracted him he would work on it with demonic speed, drawing it over and over again. The line had to begin in just the right way and continue with the right assurance and verve. “This is what gives his most beautiful drawings their purity and extraordinary freshness.” Anything less than perfection would be tossed on the floor. This is where Alexandre made, perhaps, his ultimate gift to posterity: he picked them up.

One of the drawings in the collection, curiously, not given to her but to Paul Alexandre, was of Maud Abrantes writing in bed. Her classical, almost Roman profile is revealed as she concentrates on a letter, which is barely indicated. The drawing is concerned with her intensity of focus and the expressive curve of her shoulder as she bends over her task. Paul Alexandre cautiously sketches in his own bare outline: she sat for Modigliani, came regularly to the rue du Delta for about a year, and drew when she felt like it. She returned to New York in November 1908. There is one postcard from her to Alexandre, written in French on the ocean liner La Lorraine. It says simply, “Are you still reading Mallarmé? I couldn’t tell you how much I miss all those charming evenings we all spent together around your warm fire. Oh what a wonderful time!” She was pregnant. Alexandre wrote, “We never saw her again.”

Several biographers have asserted that Alexandre acted as Modigliani’s doctor. His son Noël denies this. There was no reason for any medical attention; Modigliani’s tuberculosis was in complete remission and he was seldom ill. The other assertion, popularly made, that he either became an alcoholic on arrival in Paris or already was one, was also not true. Numerous witnesses, Soffici and Ludwig Meidner among them, make it clear that he only drank in moderation. Charles-Albert Cingria, a writer, said, “Certainly he drank … but no more nor less than others at that time.” Latourette said that he liked Vouvray or Asti, but in moderation. Noël Alexandre said, “You know when one is poor and the work is hard, a glass of wine is just the thing. It is nourishing and gives you back your strength. It’s what poor people do.”

As for drugs Modigliani experimented with hashish along with everyone else. Once while under its influence he drew a series of marionettes, so-called, formally posed figures reminiscent of Rousseau’s The Wedding, in which the participants have become so abstracted they look like statues. The crowd in the Delta also liked the idea and experimented with it. However, Modigliani seldom drew while taking hashish, preferring to recall his visions in sobriety with the aim of reproducing the heightened effect. Sometimes the borderline between sobriety and intoxication was blurred. Alexandre remembered the night when they were on their way back to Montmartre in the Métro and a train burst onto their station platform. “It was as if an amazing orchestra with millions of extraordinarily powerful cymbals had swept in like a whirlwind.” There are, from time to time, references to a small amount of cocaine that Modigliani was said to have carried. Again, this was an age when drugs were in general use, treated like snuff and used accordingly.

Brancusi, 1905 (image credit 6.13)

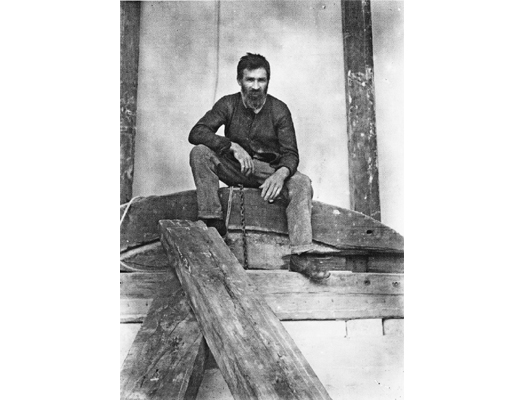

The person who did need Alexandre’s professional help was another close friend, Constantin Brancusi. This sculptor, now considered “one of the most original, persuasive and influential sculptors in the history of art,” was that rarity, an authentic genius from a peasant family, minimally schooled, unintellectual, and intuitive. He began by learning the traditional methods of working in wood in his native Romania and showed such promise that he was awarded a scholarship to the National School of Fine Arts in Bucharest. At the end of his studies, his goal was Paris. He actually walked most of the way, via Vienna, Munich, Zurich, and Basel, working as a farm laborer in exchange for a meal or a bed for the night in a barn. He arrived in Paris in 1905 when he was twenty-nine and enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts, then began to exhibit at the Salon d’Automne.

Brancusi never lived at the rue du Delta but he and Alexandre would walk in the woods at Clamart, talking constantly about art. In contrast to the Cubists, who wanted to break up and rearrange the visual image, Brancusi believed with Nicolas Boileau, a seventeenth-century French poet and critic, that “rien n’est beau que le vrai”—nothing is beautiful but the true. His whole effort was “to preserve the integrity of the original visual experience,” Herbert Read wrote, and to reduce the object to its essentials. One of his first successful sculptures, The Kiss (1908), directly carved from a single block of sandstone, was passion reduced to its essentials, the unity of two locked in a single embrace. Read wrote, “The egg became, as it were, the formal archetype of organic life, and in carving a human head, or a bird, or a fish, Brancusi strove to find the irreducible organic form, the shape that signified the subject’s mode of being, its essential reality.” Searching for the reality behind appearances: this, in Modigliani’s case, was wedded to his belief in art as a magical force offering the path to exorcism and transfiguration. “Then glut thy sorrow on a morning rose.” Brancusi and Modigliani were destined to be friends.

Brancusi had taken a studio in the Cité Falguière, rue de Vaugirard, a ramshackle huddle of artists’ studios that had, as its few compensations, some north-facing windows. He was scraping together a living in restaurant kitchens, perhaps as a plongeur, that miserable existence described by George Orwell in Down and Out in Paris and London. Brancusi, who looked, Anaïs Nin wrote, “like a Russian muzhik” with his Santa Claus beard, found work unloading at the docks, polishing floors, and doing other manual labor. According to Latourette Modigliani occasionally found part-time work making photographic prints and retouching paintings. Alexandre denied that Modigliani ever did any kind of work. “He was a born aristocrat. He had the style and all the tastes. It was one of the paradoxes in his life: loving wealth, luxury, fine clothes, generosity, he lived in poverty if not misery. It was just that he had an exclusive passion for his art.”

One suspects that the notion that because he was so brilliant others should support him became a conviction. If so it was a viewpoint Alexandre supported by giving him special treatment. The only work on display at the rue du Delta was Modigliani’s—no one else’s, and obviously resented. It led to a fierce argument during which Modigliani broke some sculptures by Drouard and Coustillier. Alexandre is probably right in thinking Modigliani had “a taste for danger,” as splendidly exemplified by Uncle Amédée. In common with Frank Lloyd Wright, a crisis seemed to be regarded as a personal test; it almost seemed a necessity. Speaking of such special personalities, Anthony Sampson wrote in The Changing Anatomy of Britain, “[T]hey have to feel they’ve got their backs to the wall to perform properly. If they make a lot of money they have to get rid of it, like gamblers, so they’re at risk again.” Such an explanation would, to some extent, account for the reckless ease with which money flowed through Modigliani’s fingers, his courting of dangers within and without, his self-defeating behaviors, and his ability to endure.

There was another reason. Modigliani’s attitude, rare nowadays, was perfectly acceptable in his day, almost commonplace. In Bohemian Paris, Jerrold Seigel writes that the poet Chatterton, who died in poverty, and whose life was celebrated in Alfred de Vigny’s play of the same name, had lost status at a time when trade and the profit motive had supplanted all other values. In a former age artists might never be rich, but they could count upon the patronage of the church or the aristocracy and were honored and valued. Now art had become a commodity, to be sold for whatever the market could bear, and the artist a sort of tradesman with no special claim to respect or status.

Nevertheless, the belief that art was still a noble cause, in stark contrast to the grubby, money-focused goals of the bourgeoisie, went to the heart of the Bohemian creed. Ordinary men and women, destined to spend their lives in numbly repetitive work, looked at the Bohemian and saw a man frittering his life away in idleness, indulging in drugs, drink, and loose women. From the other side the view was equally uncompromising. Any artist who put himself up for sale was prostituting his talent and had lost his soul. Most people could not possibly understand what inner demons drove the artist toward heights he would, perhaps, never attain. The fact that he was not bound by bourgeois standards of love and morality meant nothing. The artist’s standards for himself were higher, on a more elevated plane. He was the true hero of the age in La Dernière Aldini, by George Sand, a novel loosely based on the career of her son-in-law, the sculptor Clesinger. As it turned out she had chosen a particularly bad example in this profligate personality whose derelictions included abandoning his wife. Never mind. An artist could not be judged, since his allegiance was to a larger cause. Balzac wrote, “Bohemia has nothing and lives from what it has. Hope is its religion, faith in itself its code, charity is all it has for a budget.”

At the rue du Delta on New Year’s Eve of 1908 they had prepared for a big party for weeks. The house had been decorated by Doucet. A barrel of wine, of some nondescript vintage, was hauled in and there was all kinds of food as well. There was also hashish, which, as Dr. Paul Alexandre recalled, took the evening quite out of the ordinary. He remembered seeing Utter dancing, his blond hair flying, and he could have sworn that flames were flickering around his head. He also recalled seeing Jan Marchand stretched out on a sofa. His arms were wide open and he was moaning and weeping. Someone had told him that, because of his beard, he looked like Christ on the cross. Having had too much hashish, he believed it. Modigliani, Alexandre added as if that went without saying, dominated the evening.

It did not seem to matter to Modigliani that he was hounded by debts, sleeping on the run, with no money for food and no buyers for his drawings. He was surviving somehow. Occasionally he curled up in the street, as his friends discovered one morning. He had found a cosy corner underneath a table on the terrace of the Lapin Agile and was dead to the world. Perhaps he shared the feelings of Henri Gaudier-Brzeska when he was launched on his real work at last. The sculptor wrote from Paris in 1910, “I am right now in the midst of Bohemia, a queer mystic group, but happy enough; there are days when you have nothing to eat, but life is so full of the unexpected that I love it.”