The Serpent’s Skin

The morning is wiser than the evening.

—RUSSIAN PROVERB

DURING THOSE EARLY YEARS in Paris Modigliani’s ability to find friends who made it their mission in life to care for him was, as ever, unparalleled. It was a testament to the appeal of his personality but also the persuasiveness of his convictions and the sense that here was an important artist. This made it possible for him to subsist on the margins in Paris even though (incidentally) it did nothing to curtail his ability to empty his pockets. He had not yet found a dealer or sold his work on the open market. One day he would; it was only a matter of time. Meanwhile there was always a fire at the rue du Delta, there was a meal and a glass of wine, and, when all else failed, there was a bed with the mice and rats in Rosalie’s kitchen.

Just how seriously Paul Alexandre in particular took his self-imposed role is a case in point. Early in 1909 he left for Vienna, where he planned to spend a year conducting research in his specialty, dermatology. But he was not going to leave before asking his brother Jean to “keep an eye” on Modigliani, meaning, make sure he was eating. Jean, two years Modigliani’s junior, then studying to be a pharmacist, was living at home and working part-time. The assumption that Jean would take over the care of someone older than himself was probably accepted good-naturedly. But Jean lacked his brother’s rueful awareness that, with Modigliani, whatever could go wrong, would. Shortly after Paul’s departure, Jean wrote to say “I let three or four days go by without going to his studio. On the fifth day I found my Modi in desperate straits, three sous in his pocket and nothing in his stomach. I could just imagine the rest, so I lent him 20 francs.”

Paul Alexandre’s younger brother Jean, who was destined for an early death (image credit 7.1)

That spring of 1909 they saw each other often. They went boating on the Marne and Jean often treated “my Modi” to an evening at the theatre. They went to the Odéon to see Marivaux’s Fausses Confidences, whose psychological subtleties appealed to the artist. The other play on the bill, a medieval drama by Calderón, much admired by Jean, left Modigliani cold.

There were almost daily visits to exhibitions, trips to the Salon des Indépendants, an exhibition of their friend Le Fauconnier’s in the rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, Durand-Ruel’s, where there was a spectacular exhibition of Renoirs, to Brancusi’s studio and much else. Jean, who was working part-time and studying the rest, could not understand why Modigliani “trailed around” so many galleries, neglecting his work. If only he would stop wasting his time and pull himself together—this was an underlying theme of the two or three lengthy letters of Jean’s that have survived. Jean referred to the “instability you were aware of before you left,” a tantalizing reference that is not explained. He was becoming irritated by Modi’s ability to make money disappear and then embarking on “the usual credit system” at his paint supplier’s and restaurants. He would then appear at Jean’s door with empty pockets, and Jean, after all, only had his weekly wage.

How simple it would be if Modi could be persuaded to work! Jean knew plenty of artists who managed. Henri Gazan, habitué of the Delta, had a standing agreement to create drawings for the influential magazine Gil Blas and other “neighborhood rags,” which helped with the monthly bills. Jean knew the editor of L’Assiette au Beurre, an illustrated weekly magazine of political satire that employed several artists to provide caricatures accompanied by pithy and amusing descriptions. It seemed logical to introduce the two men. But, Jean wrote, “I don’t need to tell you that Modi, faced with the prospect of having to submit his drawings, never wants to go back there.” The issue had been settled long before. As Modigliani wrote to Ghiglia, “Your real duty is to save your dream.”

Jean was aware that “my Modi” was already receiving support from his family in the form of commissions. There was the matter of a portrait Modigliani was painting of him. He had also been commissioned for a portrait of Jean’s aristocratic girlfriend, the Baroness Marguerite de Hasse de Villers, an accomplished horsewoman. Modigliani had begun work on both commissions, was making preparatory sketches, money had been advanced, and Jean, whose interests centered around his exams, Marguerite, the next Quat’z Arts ball, and not much else, could have been forgiven for thinking his caretaking duties had been discharged.

When he visited the studio, Jean wrote in March 1909, Marguerite’s portrait had been sketched onto the canvas and looked as if it would make a wonderful composition. “As for my portrait, it would have been better if Modigliani didn’t attach such enormous importance to it. I had great difficulty in preventing him from chucking it on the fire … But I’m afraid he doesn’t use his time very well, and without counting the times he’s completely broke (like last week) when he can’t get anything done, there are others, like yesterday, when he spends the whole day out of doors.”

Jean knew that a daily progress report on what Modigliani was painting was of intense interest to his brother. Paul had helped Modigliani prepare for the twenty-fourth Salon des Indépendants in the spring of 1908. Modigliani showed a drawing, a study, Idol, two nudes, and a painting, The Jewess. This curious work shows a woman, naked from the waist up, who may or may not be wearing a hat, with a broken nose, coarse lips, and heavily lidded eyes. The composition is set down in pastel blues and outlined with crude brushstrokes in black, on the verge of caricature. Its title and the manner of its depiction would suggest that some self-loathing was involved. At any rate, it is entirely out of character with any portrait that comes before or afterward. If Modigliani had hoped to make a mark, as he had so calmly expected in the letter to his brother, he was disappointed. There was no review and nothing sold.

The caricatural approach to character displayed by The Jewess is entirely absent from the portrait of Jean Alexandre, painted in 1909. The young student who, with his wide cheekbones, low forehead, full lips, and deeply set eyes, bears scant resemblance to his father and brother, sits facing the viewer. He supports his head against an arm, and his look is pensive. Although Modigliani struggled with the portrait the implication, from Jean Alexandre’s letters, is that the one of Marguerite, The Amazon, gave him even more trouble. Jean wrote, “The portrait seems to be coming along well, but I’m afraid it will probably change ten times again before it’s finished.” The sitter, obliged to pose for hours in the Cité Falguière studio, to which Modigliani had moved to join Brancusi, was becoming mutinous. So Modi finally agreed to transfer the sittings to Jean’s room in the rue du Delta, where Marguerite could at least change into a riding habit and back again with some semblance of privacy. She finally gave Modi an ultimatum. She was leaving in a week’s time and he had to finish. So he complied. The resulting portrait of her, hand on hip, has bold conviction but is not sympathetic. Perhaps the artist saw her as men of his age would have done, that is, too independent-minded for comfort.

Modigliani painted Maurice Drouard, another habitué of the rue du Delta. His compelling study in blacks and strong background blues heightens the effect of Drouard’s almost hypnotically blue-eyed stare. There was another beautifully realized study, of Joseph Levi, a painter and picture restorer in Montmartre. Levi often lent Modigliani money, and the artist reciprocated with a forceful portrait of almost tactile strength and immediacy, in slashes of scarlet, ocher, and black. The blunt brushstrokes suggest a brief experiment with Fauvism, probably after a close study of Matisse and Derain.

Modigliani’s style was constantly shifting. There was the seated nude of a young girl, slumping forward as if shrinking from the viewer’s gaze, the whole Gauguinesque in its sumptuous use of pastels: soft pinks, mauve-grays, blues, and blue-greens. Modigliani thought so little of this small masterpiece that he used the back of the canvas for something else. The influence of Toulouse-Lautrec, evident in his drawings, can also be seen in an early profile portrait of a girl and of Cézanne in The Beggar of Leghorn. The unpromising subject has been transformed by a virtuoso display of color: high blues and grayed-off greens.

Modigliani was also experimenting with nude studies and, since sitters were expensive, was looking for compliant subjects wherever he could find them. One was “La Petite Jeanne,” another waif the Alexandre brothers had taken under their wing. A young girl recently arrived from the country, Jeanne was working as a model in art schools and had had the bad luck to be infected with a venereal disease for which she was being treated. Just then she was in the hospital with a case of German measles and being visited by Jean and Modigliani. The artist assumed the role of immortalizing her in paint. There were two nude studies, one of which was sensitively analyzed by Jeanne Modigliani. “The reserved expression of the sulky little face on its cylindrical neck, the calm solidity of the forms, the slightly asymmetrical displacement of the figure to the left, the extremely simple but shrewd organization of the background into two zones … her two breasts, one perfectly round, the other conical … all these make a perfectly balanced work whose style is thought out to the last detail.”

Perhaps the most fully realized of his portraits at this period is Beggar Woman, an example of the “cool purposefulness” and economy of means that Modigliani was beginning to display. The lowered eyes, droop of the head, and particular set of the mouth speak volumes about the misery and pride of this anonymous daughter of the people. Before Modigliani finally finished Jean’s portrait he gave the painting to the latter and dedicated it to him “to keep him happy.” Jean hung it on a wall of the rue du Delta along with all the other Modiglianis (interspersed with photographs of Raphaels), to the resentment of other inhabitants. The Quatz’ Arts ball was imminent, but so were Jean’s exams. Parties had fallen off at the Delta along with Paul’s Saturday gatherings. Everything was uncharacteristically quiet. Besides, Paul had his suspicions about how well Modi was being looked after. Three months later, to parental astonishment, Paul cut short his Viennese studies and came home.

With his probing and sensitive studies of character as exemplified by his portraits of the Alexandre father and sons, Maurice Drouard, and others, Modigliani had demonstrated his mastery of the delineation of character at an early stage. He was arriving at the end of a long line of masterful portraitists from Whistler and John Singer Sargent to Mary Cassatt and Cecilia Beaux. But the ways in which any artist could make his mark in this genre—once considered second only to large-scale narrative painting or depictions of the lives of saints—was coming to an end. There had to be a new approach, and Gauguin, Cézanne, Matisse, and Picasso thought they had found it. The secret was to be revealed in African sculpture. Most of it, from the west or central areas of the continent, had been arriving in Europe in vast quantities since the 1870s and was so little valued that it could be picked up for small change in any flea market.

Artists, however, were beginning to look at these curious objects with fresh eyes. Gertrude Stein recalled that Matisse had discovered a Vili figure from the Congo in a curiosity shop in her Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1913). Barely a year later, in 1907, Picasso began making repeated visits to the African collections at the Musée du Trocadéro. Like Matisse, Gauguin had also been attracted to the fragmented, Cubistic shapes, the pictorial flatness, and the spiritual component that they both recognized in the work, all of which suggested startling new possibilities.

Modigliani’s own interest began when he saw samples of African art in the shop of an art dealer, Joseph Brummer. Then he, too, went with Paul Alexandre to the Trocadéro to see the Angkor exhibition in the Occidental wing.

Alexandre wrote that what appealed to Modigliani about these primitive sculptures with their masklike faces had to do with simplification and purification, i.e., a search for the irreducible organic form. “I remember that he would stop … in the place Clichy to admire those naive coloured pictures that were sold by Arabs, always showing the same landscape: a small bridge between two mountains. This search for simplification in drawing also delighted him in certain paintings by Douanier Rousseau or in Czobel’s figures from fairground stalls.”

Frank Burty Haviland, himself a collector, painter, and friend of Picasso’s, whom Modigliani would paint, owned an extensive collection of African sculptures. According to Adolphe Basler, “they captivated Modigliani; he could not see enough of them. Soon he could think only in terms of these forms and proportions. He was transfixed by the pure and simple architectonic forms of the Cameroonian and Congolese fetishes, of those attenuations found in the elegantly stylized figurines and masks along the Ivory Coast.”

The comment reveals that Modigliani also intuitively understood the mask’s symbolic possibilities. These objects, after all, were embodiments of ancestral spirits that they represented. They were, as Picasso wrote, “magical objects … The Blacks were intermediaries, ‘intercessors’ as I have since learnt. Against everything, against unknown and threatening spirits.” Masks were amulets that protected one from the very evil they summoned up and represented. They were powerful in themselves, and they conveyed power.

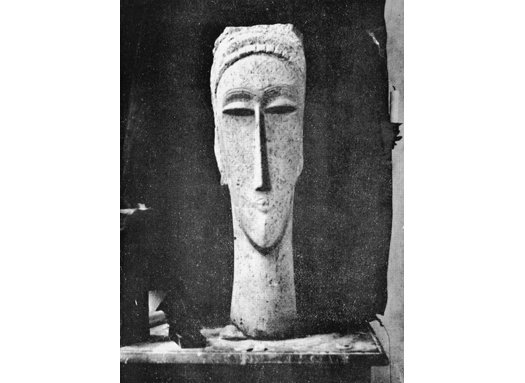

It is axiomatic that the dandy and the actor had much in common; both are concerned with the protective mask of appearance. With Modigliani it is always hard to say which impulse dominated since both were marked traits of character. So it is not surprising that the theme of the mask should make a dramatic appearance at this time. Like the Baule sculptures from the Ivory Coast which they resemble, their slender silhouettes are elongated, faces triangular, with dominant noses, puckered lips, low foreheads, and eyes spaced far apart. Hair is pulled into tightly controlled shapes, sometimes embroidered with geometrical designs, ears are barely suggested, and the head is balanced on an exaggeratedly long neck. Like Modigliani’s marionette studies, inspired by Rousseau’s painting of a wedding party, the stonelike stares are unreadable. Yet something important has been achieved. Worship and sacrifice had endowed these African models with an uncanny potency. Modigliani had almost died, and something of that peril and suffering had, perhaps, infused his own creations with a premature gravity. The results, according to Alfred Werner, showed a “majesty and greatness … in a way reminiscent of ancient Egyptian or archaic Greek sculptures.” The masklike heads with their locked expressions were silent witnesses to Modigliani’s most secret concerns, the mysteries of life, death, and rebirth. Modigliani was not alone in attempting to go far beyond literal pictorial or sculptural representation. Honour and Fleming describe Monet’s semi-abstract painting Water Lilies in the same way. The painting’s “almost spaceless views downwards, on to and through the surface of the pool” bear “intimations of infinity.” Much the same poetic insights give depth and dimension to Modigliani’s wonderfully strange sculptural experiments, his own investigations into “an endless whole.”

One of Modigliani’s early experiments in sculpture (image credit 7.2)

Modigliani began his short career as a sculptor with the passion and determination that showed in everything he did. “The intensity of his attention to forms and colours was extraordinary,” Alexandre wrote. “When a figure haunted his mind he would draw feverishly with unbelievable speed, never retouching, starting the same drawing ten times in an evening by the light of a candle.” He sculpted in the same way. First he made endless sketches. Then, as before, and unlike Brancusi, who modeled first in clay, he worked directly on stone blocks that often were “liberated” from building sites and taken back to his studio in a wheelbarrow. Technical advice was always available, either from Drouard at the Delta or, most likely, from Brancusi, his neighbor at the Cité Falguière. Almost all of the twenty or so known sculptures are carved in a limestone known as “Pierre d’Euville,” quarried near a small town in eastern France, which is softer and easier to carve than marble. A few were in wood, also scavenged (or so it is also said) from the railroad ties being stockpiled for a nearby Métro station at Barbes-Rochechouart. And almost all are heads. There exists a sixty-three-inch statue of a woman, her arms cradled to suggest a Madonna sans baby, that may be a witness to the fact that the artist had ambitions he could not afford to realize. Given Modigliani’s chronic dissatisfaction with his work, the fact that he was constantly on the move and that sculptures are heavy, the wonder is that any survived. As it is these images seem to have sprung from his imagination almost fully formed, which, according to Alexandre, would not have satisfied him. He was looking for the “definitive form” that, Alexandre believed, he never attained. “He never abandoned an idea. But a finished work, if it was successful, soon left him indifferent. He would immediately move on to another.”

The sculptor Jacques Lipchitz, who visited Modigliani often in his studio at the Cité Falguière, wrote,

Modigliani, like some others at the time, was very taken with the notion that sculpture was sick, that it had become very sick with Rodin and his influence. There was too much modeling in clay, too much “mud.” The only way to save sculpture was to start carving again, direct carving in stone. We had many very heated discussions about this, for I did not for one moment believe that sculpture was sick, nor did I believe that direct carving was by itself a solution to anything. But Modigliani could not be budged; he held firmly to his deep conviction … When we talked of different kinds of stone—hard stones and soft stones—Modigliani said that the stone itself made very little difference; the important thing was to give the carved stone the feeling of hardness, and that came from within the sculptor himself: regardless of what stone they use, some sculptors make their work look soft, but others can use even the softest of stones and give their sculpture hardness. Indeed, his own sculpture shows how he used this idea.

It was characteristic of Modigliani to talk like this. His own art was an art of personal feeling. He worked furiously … without stopping to correct or ponder. He worked, it seemed, entirely by instinct—which was however extremely fine and sensitive, perhaps owing much to his Italian inheritance and his love of the painting of the early Renaissance masters.

The British sculptor Jacob Epstein knew Modigliani well and, at one point, spent months with him looking for sheds where they could work together in Montmartre in the open air. “Our enquiries about empty huts only made the owners … look askance at us as suspicious persons,” Epstein recalled. “However we did find some very good Italian restaurants where Modi was received with open arms. All Bohemian Paris knew him. His geniality and esprit were proverbial … His studio at that time was a miserable hole within a courtyard and here he worked. It was then filled by nine or ten of those long heads which were suggested by African masks and one figure. They were carved in stone. A legend of the quarter said that Modigliani, when under the influence of hashish, embraced these sculptures.”

As for Lipchitz, “I can see him as if it were today, stooping over those heads of his, explaining to me that he had conceived all of them as an ensemble. It seems to me that these heads were exhibited later the same year (1912) in the Salon d’Automne, arranged in step-wise fashion, like the tubes of an organ, to produce the special music he wanted.” Artists were the first to recognize that Modigliani was doing important work. Augustus John, who saw the same heads at about the same time, was equally impressed. “The stone heads affected me deeply. For some days afterwards I found myself under the hallucination of meeting people in the street who might have posed for them, and that without myself resorting to the Indian Herb. [A reference to hashish.] Can ‘Modi’ have discovered a new and secret aspect of ‘reality’?”

Modigliani paid several return visits to Livorno in the next few years, the first in the summer of 1909. Even Jeanne Modigliani, who had the benefit of cross-references in the private family correspondence, decided that the situation was hopelessly muddled. No one knew exactly how often he returned in the years before 1913, not to mention the precise state of his health.

Writing in 1941 in Artist Quarter, Charles Beadle, a sporadic witness to actual events, described the day when friends found Modigliani collapsed and unconscious in a studio and contributed the money to send him home, dating this as the summer of 1909. Other evidence has established that this incident, which certainly happened, must have come later. A postcard from Eugénie to Emanuele’s wife Vera, announcing Modigliani’s return, adds, “He seems very well.” Other correspondence, with Paul Alexandre, establishes that Modigliani was in Livorno for three months, returning to Paris at the end of September.

Dedo might have been slightly run-down. He certainly needed a new wardrobe, and Caterina, the family’s dressmaker, known for her foul mouth and expert tailoring, came in by the day. She was put to work on clothes for Dedo, although Margherita claimed that her brother “was extravagant and ungrateful. He shortened the sleeves of a new jacket with one slash of the scissors and tore out the lining of his Borsalino to make it lighter.”

By then Dedo had become a drain on the family’s purse with no end in sight. Douglas also states that Umberto Brunelleschi, a painter friend of Dedo’s youth, hearing of his desperate state, sought out Emanuele Modigliani in Rome to present the story. Brunelleschi reported that Emanuele was not sympathetic: “Je m’en fous. I don’t give a hoot. He’s a drunkard and his drawings make me laugh.”

Given the notorious unreliability of reported speech it seems possible, just the same, that any appeal to Emanuele for more money would not have been well received, since he and Umberto had been helping to support Dedo for years. There seemed to be precious little to show for the economic sacrifices they were all making. Any sensible artist/sculptor would have found some part-time work, if only out of desperation. Emanuele took matters into his own hands, Douglas continues. He found his brother employment as a sculptor, working on marble in Carrara, all expenses paid. Dedo still refused to take the hint. It is not surprising that Emanuele did not bother to find out what was remarkable about his brother’s art—if anything.

That summer Dedo was spending his days at the atelier of his friend Gino Romiti, writing philosophical articles with his aunt Laure, and painting, although just how many canvases he produced is unknown. He wrote to Paul Alexandre early in September: “I sent you a card from Pisa where I spent a divine day. I want to see Siena before leaving. Received a card today from Le Fauconnier. He wrote four absolutely extraordinary lines of nonsense about Brancusi which pleased me enormously.” He wanted registration forms for the Salon d’Automne and told his “very dear Paul” where to get them. He tried to appear offhand: “To exhibit or not to exhibit, deep down it’s all the same.” Nevertheless he wanted news of the Salon. He was in high spirits and secretly thrilled to be returning to Paris soon. Paul would find him restored, he wrote, not just physically, but sartorially as well—underlined.

There is reason to think that while in Livorno Modigliani was also sculpting. Gastone Razzaguta, who believed he met Modigliani in about 1912 or 1913, recalled that the latter passed around photographs of his sculptures. He was evidently proud of them and expected compliments but, “we didn’t understand them at all.” When Modigliani told Razzaguta he needed a large room where he could go on sculpting, “we thought it was just another of his crazy ideas.” But Modigliani kept asking and finally a room was found. His friends even obliged by carrying in some blocks of raw material, actually paving stones.

“Dedo, who was like a ghost with us, who appeared and disappeared, from the day he got that big room and the stones … we didn’t see him again for some time. What he was doing with those stones we never knew. But he must have been doing something because when he decided to return to Paris, he asked us where he could store the sculptures.” Razzaguta claimed that Modigliani’s friends never saw the results, but Bruno Miniata said that he had indeed shown his work around.

Dedo had arrived late at the Caffè Bardi where we used to meet. It was hot—summertime. We left and were walking along beside the Fosso Reale (Royal Moat) toward the Dutch church. At some point Dedo pulled a stone head with a long nose from its newspaper wrapping. He showed it to us as if he was showing us a masterpiece and waiting to hear our opinions.

I don’t remember exactly who it was—Romiti, Lloyd, Benvenuti, Natali, Martinelli or even Vinzio Sommati. There were a number of us—the usual crowd. Everyone burst out laughing. They were teasing poor Dedo about that head. Without a word Dedo threw it over his shoulder into the water below.

It could have been a single head or two or three. Some said that Modigliani had piled a wheelbarrow full of sculptures, pushed them down the via Gherardi del Testa, and dumped the whole thing in the canal. The accounts varied, but the point of the story was how ridiculous the work was and how its creator had been shamed into destroying it.

One art historian, Vera Durbè, curator of the Museo Progressivo d’Arte Contemporanea in Livorno, believed that the story was true. In 1984 the city fathers were marking the centenary of Modigliani’s birth with exhibits, conferences, and seminars. Why not seize the opportunity to dredge the Fosso Reale? What a coup it would be if three unknown sculptures could be found. The council agreed and work began.

To everyone’s astonishment, a battered wheelbarrow and three sculptures emerged from the murky water. They were in stone. They had the eyes, the elongated noses, and the enigmatic expressions of Modigliani’s mature style. They were suitably blackened by mud and blotched with rust, apparent proof of decades of immersion. They had to be real. Vera Durbè wept when she saw them. Numerous prominent art historians rushed into print. The sculptures were “treasures,” “magical faces,” “splendid primitive heads,” no less than “a resurrection.”

A preparatory sketch for The Cellist, 1910 (image credit 7.3)

So much for expert opinion. In a few weeks three young pranksters: a medical student, a business student, and an aspiring engineer said they had built the fakes themselves using hammers, chisels, a screwdriver, and a Black and Decker electric drill. They described how they had “aged” the fakes. The critics, their reputations at stake, demanded proof. The forgers, on television, reconstructed new masterpieces in about four hours. Vera Durbè collapsed and was hospitalized. Everyone else had a good laugh. Black and Decker subsequently ran some sly commercials juxtaposing the drawing of an abstract head with the comment, “It’s easy to be talented with a Black and Decker.”

Whether Modigliani was really a sculptor who painted, or a painter who experimented in sculpture will never be settled. What is clear is that, even at the height of his absorption with sculpture he was still painting. Late in 1909 he completed a canvas which caused a genuine stir when it was exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants in 1910. Some powerful preparatory sketches of a seated cellist in Chinese ink and black crayon have survived in the Alexandre collection. The unknown sitter—believed to have been renting a room next door to Modigliani’s in the Cité Falguière—is young, bearded, and completely absorbed in his task. The sketches show that the composition was diagonal from an early stage, the details simplified to their essences, an idea which continues to the finished work, which Modigliani painted in two slightly different versions. The artist’s focus is on the communion of artist with his instrument and the background: the addition of a fireplace, mirror, wallpaper, and bed, is subordinate. Jeanne Modigliani called it “one of the most complex and significant works of a period in which all his contradictory tendencies met. The contrast and balance between the cool harmonies of green, blue and gray-white and the warm browns, reds and ochres; the composed lines of the face and the interminable curve of the arm; these all balance the volumetric density of the cello.” The influence of Cézanne is clear enough, but as Werner Schmalenbach observed, it is an influence more transmuted than direct and already on the wane.

Along with The Cellist Modigliani exhibited five other paintings at that exhibition: the Beggar of Leghorn, Lunair, two studies, and Beggar Woman, the painting he had given to Jean Alexandre. The poet Guillaume Apollinaire singled him out in a column for L’Intransigeant and André Salmon did the same in Paris Journal. Two people had seen fit to distinguish him from the pack—there had been six thousand entries. He was on his way. Or was he? If Modigliani had hoped to find a dealer he was disappointed; nothing sold. Paul Alexandre was still his only patron.

Modigliani continued to create new heads. Roberto Rossi had a studio opposite his in the Cité Falguière for a time and remembered the terrible heat of the summer of 1911, when it was too hot to do anything but they hammered away anyway. Each day he would find Modigliani outside on a small embankment, at the same task. As the days wore on the resulting heads became increasingly abstract until the Modigliani nose, simplified to a triangle and longer by the hour, was almost all that was left.

Each day Rossi would say teasingly, “Amedeo, don’t forget about the nose!” and Modigliani would refuse to laugh. After Rossi moved to the boulevard Quinet in the fourteenth arrondissement they would meet over a glass of wine at a small café in front of the Cimetière du Montparnasse and Modigliani would invariably ask for a loan. At one time, Rossi said, he was owed a considerable amount of money, but was good-naturedly in no rush to call in the debt.

“One day he knocked at my door with a roll of drawings under his arm. He wanted me to accept them in payment of his debts … and, to overcome my resistance, threw the roll on my desk. I gave them back to him, assuring him he did not owe me anything. He would not listen. Once again he threw the roll on the desk and headed for the door.” It was clear that the payment was far in excess of the money owed. He adroitly threw the roll at Modigliani’s feet. Modigliani conceded defeat and retrieved it, “muttering his usual ‘Porca Madonna,’ ” Rossi concluded. “And that’s why I don’t have a single memento of my friend.”

Rossi recalled another occasion when he and a woman friend went to see an exhibition of paintings by Baron Antoine-Jean Gros at a fashionable gallery on the rue La Boétie, where the entrance was being guarded by “a costumed servant with a half-moon face.” They happened to appear just as Modigliani was about to go in. Rossi and his friend were respectably dressed; the artist was in a wrinkled shirt with no tie. The servant held up his hand, as if prepared to eject him by force. “Porca Madonna … Se lo vada a pigliare in culo!” Modigliani swore, and left. Whether or not the servant understood the insult is not recorded.

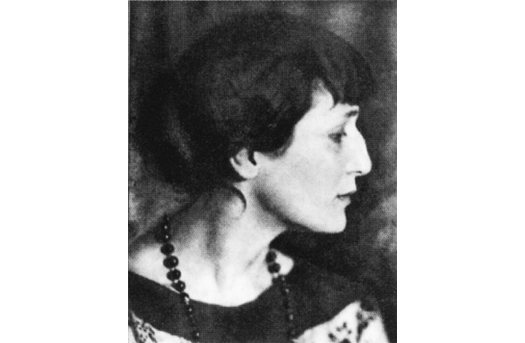

In the spring of 1910 an unknown poet, aged twenty-one, arrived in Paris for her honeymoon. She had been born Anna Gorenko, daughter of a naval engineer, and began writing poetry at a young age. When her father objected, she took the name of a medieval Tatar prince, Akmat, a descendant of Genghis Khan, whom she claimed as one of her ancestors, becoming Anna Akhmatova. This self-invention could have been one of the factors that attracted her to Modigliani when she, wife of a prominent older poet, Nicolay Gumilyov, not yet famous herself, made her first trip to Europe.

Anna Akhmatova, 1910 (image credit 7.4)

Her reputation as “a legendary beauty of Bohemian prerevolutionary St. Petersburg” was deserved, to a point. Luminous gray eyes, an expressive mouth, and wide cheekbones guaranteed that she would be a beauty, except for one feature: an emphatic nose with a pronounced bump. The result was unexpected and somewhat unsettling, as if some stigmata had marked her for a prominent and menacing fate. Proudly, almost defiantly, she sat for portrait after portrait, none of which glossed over the truth of that singular nose. She lived through the turbulent unfolding of the Russian destiny: the revolutions, wars, tyrannies, and Stalinist firing squads. Her husband was shot on a trumped-up charge, her son endured years in labor camps, and she herself somehow survived the Siege of Leningrad. Under these terrible pressures, in the face of agony and loss, she wrote haunting poems that have assured her a lasting fame. After Leningrad, she wrote,

That was when the ones who smiled

Were the dead, glad to be at rest.

And like a useless appendage, Leningrad

Swung from its prisons.

She was tall, slender, and quiet, a woman of education and artless self-assurance, whose feelings were kept in check by an almost superhuman self-control. Her themes were love, loss, and helpless endurance; like haiku poetry, her verses give sudden glimpses into an abyss of pain. Such superb economy of means, along with a natural elegance of manner, marked her as someone quite apart, and Modigliani would have instantly recognized a kindred spirit. How they met is not recorded in a memoir that is charmingly direct and typically reticent.

What Modigliani might have found fascinating about her, she wrote, was a certain ability to “read other people’s thoughts, to dream other people’s dreams … He repeatedly said to me: ‘On communique.’ [We understand each other.] And often, ‘Il n’y a que vous pour réaliser cela.’ [Only you can manage that.]” He also said matter-of-factly, “J’ai oublié de vous dire que je suis Juif.” [I forgot to tell you I’m Jewish.]

For her part, she continued, it is likely “that neither of us understood one essential thing: that everything that was happening was the pre-history of both our lives: his—very short, mine—very long. The breath of art had not yet charred, not yet transformed our two existences; this should have been the light, bright hour that precedes the dawn. But the future, which as we know casts its shadow long before it appears, knocked at the window, hid behind lampposts, cut through our dreams, and threatened with the terrible Baudelairian Paris concealed somewhere nearby. And all that was divine in Modigliani only sparkled through a sort of gloom.”

Curiously, she too thought he had the head of Antinous, “and in his eyes was a golden gleam.” He was, she concluded, “unlike anyone in the world. I shall never forget his voice.” She was on her honeymoon, but her husband was involved in lectures and conferences, and Modigliani was an eager presence. A year later, in the summer of 1911, she returned and they saw each other constantly.

And fame came sailing, like a swan

From golden haze unveiled,

While you, love, augured all along

Despair, and never failed.

—“TO MY VERSES” (1910)

To her, he seemed very lonely. There was no girl in his life just then, and he seemed to know almost no one, even in the Quartier Latin, where everyone more or less knew everyone else. He had the most perfectly exquisite manners. Published in the 1960s, just before her death, her memoir was, in part, an indignant defense against the prevailing view of Modigliani; she never saw him drunk, she wrote firmly. What she could not understand was how he had survived. Although the child of middle-class parents, she knew something about poverty, the vaporous atmosphere of the slums, as an English teacher, Alexander Paterson, described them in 1911. “It is the constant reminder of poverty and grinding life, of shut windows and small inadequate washing basins, of last week’s rain,” and the soft, relentless shower of dirt, “which falls and creeps and covers and chokes.” When they met for the second time, he had endured a harsh winter. He was thinner and his mood was somber.

They used to meet in the Jardins du Luxembourg. Renting a chair cost a pittance but it was more than he could afford, so they shared a bench. They sat in the warm summer rain under his enormous, battered black umbrella and recited Verlaine to each other, thrilled to discover that they both knew the same passages. She did not know then that Modigliani also wrote poetry, but he read hers; he confessed charmingly that he did not understand them but was sure they were very fine. Passersby pointed out the particular path in the gardens that Verlaine, followed by a crowd of admirers, habitually took. He was on his way to a café where he wrote his poems and ate lunch. He was no longer walking that path (he died in 1896), but another great man was, wearing a beautifully tailored overcoat and with the red ribbon of the Légion d’Honneur in his lapel: Henri de Regnier. Modigliani loved Laforge, Mallarmé, and Baudelaire and would recite them by the hour, although not Dante, she thought out of consideration for her, since she knew no Italian. He also recited Les Chants de Maldoror, the then-obscure work by the self-styled Comte de Lautréamont.

A period view of the Luxembourg Gardens, where Modigliani and Akhmatova met to recite poetry to each other. From an old postcard (image credit 7.5)

He took her to the place where he worked, “the little courtyard behind his studio; you could hear the knock of his mallet in the deserted alley.” When his sculptures went on view at the Salon des Indépendants in 1911 he asked her to go. So she went and found him there, but he did not approach her, she thought because she was with a group of friends. The walls of his studio were lined with “incredibly tall portraits” that seemed to stretch from floor to ceiling and which she never saw again. He was full of enthusiasms, except for whatever was in vogue at the moment. This included Cubism, which was “all-conquering but alien to Modigliani.” He took her on a tour of the Department of Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre; nothing else, he said grandly, was worth her attention. Then he made a drawing of her dressed as an Egyptian queen; he was passionately interested in all things Egyptian.

He drew her repeatedly. At one time she owned sixteen of his drawings; Modigliani told her to frame them and hang them around the rooms of her house in Tsarskoye Selo. They were lost when the house was ransacked during the Russian Revolution. Others have survived, showing that she posed for him in the nude, drawings which hint at her almost divine status in his eyes. The winter she was in Russia he wrote her long and beautiful letters. He said, “You are for me like a haunting memory.” He said he would like to hold her head in his hands and cover her with his love.

She would never have revealed her feelings in so many words but she did it in other ways. She knew that in the dead of night he would prowl the streets for hours. Sometimes he took her with him, on nights of the full moon, for instance, when they would walk behind the Pantheon and explore the old Paris. She also knew that he sometimes walked under her windows; she would recognize his step and watch his shadow lingering across the glass. One day she arrived when he was out, carrying a bouquet of roses. When he did not come to the door she threw them, one by one, through an open window. They fell on the floor so artistically he was convinced she must have arranged them herself.

Akhmatova arrived in mid-May of 1911 and returned to Russia two months later, perhaps by the end of July. At that point Modigliani’s aunt Laure appears in his life in a curious way. That was the summer that Apollinaire, working in a bank, sold a few pictures for him. This may have led Modigliani to mention something to Laure about making a visit to the French countryside. Whether this happened as Akhmatova was leaving, or just after she left, the sequence of events is intriguing. According to Jeanne Modigliani, Laure Garsin found a small house for rent at Yport, a village in the Seine-Inférieure not far from the coast, and invited Modigliani there for a rest cure. He arrived in early September, in an open carriage through which he had driven in heavy rain. Naturally, he was soaking wet. But instead of resting in the cottage he insisted on making a trip to Fécamp to see the beaches. And it was still raining.

Laure was appalled at this cavalier attitude toward his health. What if he got ill again? The house could not be heated. Suppose he became bedridden? How would she find a doctor? She was in a panic and cut short their stay. Meantime, Modigliani could not understand what the fuss was about. He felt fine. Or was he only acting, as usual? What feelings of despair was he concealing? “He went out, reeling; / his mouth was twisted, desolate,” Akhmatova wrote in one of her poems of that period, “I Wrung My Hands.” He had watched her leave and had no way of knowing whether they would ever meet again; as it happened, they never did. There is a real possibility that she wanted to stay in Paris, but was as badly off as he was and there was no way he could possibly support her. What he needed just then was someone who could support him. That possibility is suggested by her comment, in old age, that “Modigliani is the reason for the tragic consequences of my life—of my whole life.”

Caryatid is one in a series of drawings, watercolors, and oils that absorbed Modigliani’s attention for two or three years (1911–13). This particular version shows a standing figure, her long nose, diminutive mouth, and almond eyes precariously balanced on a cone of neck, nude save for what could be ropes of precious stones girdling her waist and falling over her hips. She is, like his sculptured heads, expressionless. She stands, one leg slightly bent, against a background of black brushstrokes superimposed on pink flesh tones, and bending harmoniously to the outlines of her waist and full thighs.

She could be anyone—a goddess, a wood nymph, a priestess—but she is actually one in a series of female figures whose arms are raised to hold up—something. Just what is never clear. Basler wrote, “For several years Modigliani did nothing but draw, and trace round and supple arabesques, faintly emphasizing with a bluish or rosy tone the elegant contours of those numerous caryatids that he always planned to execute in stone. And he attained a design very sure, very melodious, at the same time with a personal accent, with great charm, sensitive and fresh.” The woman as prop and buttress: this was Modigliani’s repetitive image, now standing, now crouching, now bent under the weight or lightly poised beneath it.

Caryatids, in the Encyclopædia Britannica’s definition, were draped female figures used as supports for entablatures in Greek, Roman, and Renaissance architecture. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary adds helpfully that the word derives from the Latin and Greek, karyatides, literally “princesses at the Temple of Diana.” That goddess, usually depicted as about to go hunting, wearing a tunic and carrying a bow and arrow, was also that of fertility, pregnancy, and childbirth, and sometimes that of the forest and wild animals. One of her very early temples, before 495 BC, was discovered on the northern shores of Lake Nemi, on a stone terrace with niches cut in the back wall that apparently served as chapels.

Modigliani’s grand scheme was to create a “Temple of Beauty.” Since he and Brancusi were working together closely at this period it is perhaps no coincidence that Brancusi, whose own grand scheme included complete sculptural environments, also came up with the idea of a temple and worked on it for decades. Brancusi’s most elaborate design, sometimes called a Temple of Love, or a Temple of Meditation and Temple of Deliverance, was commissioned by Yeshwant Holkar, maharajah of Indore in the 1930s. Brancusi envisioned a completely enclosed space with a vaulted ceiling, a pool, and sculptures placed so as to be spotlit, at certain times of year, by sunlight focused from a ceiling opening. (It was never built.) Modigliani’s own grand schemes, if they were ever committed to paper, have not been found. But like Brancusi he was using his studio as an impromptu stage on which to calculate the precise placement of his sculptured heads, along with the caryatids, only one of which exists. (It is three feet tall and at the Guggenheim.)

One finds at least one other common theme between the work of the two men. As early as 1911 Modigliani was using a curious motif, a column decorated with geometric designs, seen in a portrait of Paul Alexandre. A symbol of the quest for the infinite, the Endless Column is an idea Brancusi took up six or seven years later. In his work it became a sculptural Tree of Life, the pillar supporting the firmament and the axis mundi on which the world turned. Restellini wrote, “Was Modigliani the originator of one of Brancusi’s major creations?”

For Modigliani the repetition of the caryatid theme would suggest allusions to death and fertility and the idea of woman as divine intermediary. Like Brancusi’s, his experiments with sculpture had a broadly ambitious goal even if his temple, too, was never built. It was an incantatory circle of stone, meant to protect and guard, sustain and inspire. The festival of Diana took place in mid-August during a full moon, and she was worshipped with torches. One of Modigliani’s girlfriends recalled dining by the light of a guttering candle, fixed to the head of a sculpture. When Epstein visited the studio it was already filled with nine or ten long heads and a single figure. Modigliani, who had spent so many nights of his young life hovering between life and death, was justifiably afraid of the dark. Epstein said, “I recall that one night, when we had left him very late, he came running down the passage after us, calling us to come back like a frightened child.” Each evening, candles fixed to each stone head would transform a squalid studio into a sacred space. One imagines him seated there in the darkness, safe in the magic circle of his imaginary temple.