Maldoror

[D]espair has won his soul and he wanders alone like a beggar in the alley.

—Les Chants de Maldoror

ONE LAZY AFTERNOON a government clerk named Gastone Razzaguta, who liked to call himself an artist, was sitting in the Caffè Bardi in Livorno eating a macaroon when a stranger walked in. The man, of average height, had a shaved head. Everybody knew what that meant, so Razzaguta was instantly on his guard—maybe he was an escaped convict on the run or something. If so, the man seemed very self-assured. His walk was nonchalant and Razzaguta relaxed, concluding that the man had been recently released.

But it was his outfit that commanded even more attention: black-and-white pinstriped trousers absurdly held up with a belt of string, a linen jacket, and, shockingly, a collarless shirt at a time when everybody wore high collars. Furthermore he was in urgent need of a shave, his beard was growing in white, and he looked around him in a demanding way. Where was everybody? “Is Romiti here? Natali?…” No reply. “But aren’t there any painters here?”

This photograph, much disputed, purports to show Modigliani with an uncharacteristic crew cut, posing with one of his sculptures, 1914. (image credit 9.1)

Somebody pointed at Razzaguta, whose long hair qualified him for the role. “He turned to me with a surprising but cordial invitation. ‘Let’s have a drink. Who pays?’ ” Razzaguta bought them each a glass of Pernod and made a point of noting in his memoir that he was not given a drawing in return.

It was the summer of 1913 and Modigliani was back in town. The clerk to the contrary, a shaved head did not necessarily imply a prison sentence but, more likely, a hospital stay in those days of rampant head lice. Modigliani must have spent weeks convalescing before being well enough to travel home in March. Umberto paid for the trip and Paul Alexandre, at 13 avenue Malakoff in Paris, stored Modigliani’s valuables. These included the majority of his finished sculptures and a precious selection of drawings, studies for new sculptures. There remained a single head, a particular favorite, that had been left in the studio of the “Serbo-Croat,” a joking reference to Brancusi. Modigliani wanted that transferred into Paul’s safekeeping as well.

Modigliani was back on his feet but still frail. Emanuele recalled, “Amedeo returned very ill, and looking like a tramp, to the horror of his poor mother. Naturally he was nursed, well fed, and brought back to a sane health.” To feel alive again was to return to work, and Dedo had a particular goal in mind. He was about to create the crowning glory of (one assumes) his Temple of Beauty, although this was not actually mentioned. The keystone, in marble, had been designed and would be achieved in the next few weeks. He was moving to a village where he would literally put up a sleeping tent. He wrote that it had “dazzling light and air of the most luminous clarity imaginable.” This may have been the year that Modigliani had his picture taken with one of his sculptural achievements. This is suggested by the fact that an undated and blurred photograph purports to show him, however indistinctly, with very short hair. One of his heads emerges from a block of stone. It is on a plinth; the author stands in the background. In the days when rich food and plenty of it was the only real defense against the ravages of tuberculosis, if this is really Modigliani, he has gained weight. There is a cummerbund around his expanding waistline and a tie around his neck. Both have to have been red. His pride in his work is palpable.

If the marble piece or pieces were ever finished, there is no record. Modigliani did not take them back to Paris when he returned in the summer of 1913 and Noël Alexandre believes this marked the beginning of the end of his work as a sculptor. As for this latest relapse, Modigliani wrote early in May that he had been resuscitated once more. “Happiness,” as he wrote, “is an angel with a grave face.”

That postcard was sent a few weeks before Jean Alexandre died of tuberculosis at the age of twenty-six. The words may have had a double significance, not just to telegraph cautious optimism but to console his friend for what must happen soon. Heavenly messengers with Janus-like faces: the capriciousness of fate was the price to be paid for earthly happiness. That year Modigliani made another reference to a subject that was much on his mind, as seen in a statement he appended to a drawing:

Just as the snake slithers out of its skin

So you will deliver yourself from sin.

Equilibrium by means of opposite extremes

Man considered from three aspects.

Aour!

The serpent shedding its skin is a common alchemical reference and the statement itself makes most sense when seen in this context. The symbol for Mercury, which follows the second line, is a reference to fluency and transmutation, the “messenger from heaven.” To alchemists, all matter was made of three constituents: mercury, sulphur, and salt; matter, being unique and universal, was one in three. The mystical importance of the number three is reinforced by the sign of the triangle. As for the six-pointed star, alchemists considered there to be four theoretical elements, earth, air, fire, and water, and this was the symbol. “But to go further and attempt to understand the meaning of the words—the new skin of the serpent, the deliverance from sin—it is necessary to consider the ultimate goal of alchemy … to obtain the Red Elixir … or philosopher’s stone which (turns) all base metals … into gold,” Alexandre continues. After numerous complicated procedures the philosopher’s stone would reach albification, or whitening, comparable to resurrection after death. “Aour!,” a corruption of the Hebrew word meaning light, would seem to be a reference to trial by fire, the necessary purification, without which “the Great Work is impossible.” Or, in the poetic terms Keats used to express his own hopes for rebirth, “But, when I am consumed in the fire, / Give me new Phoenix wings to fly at my desire.”

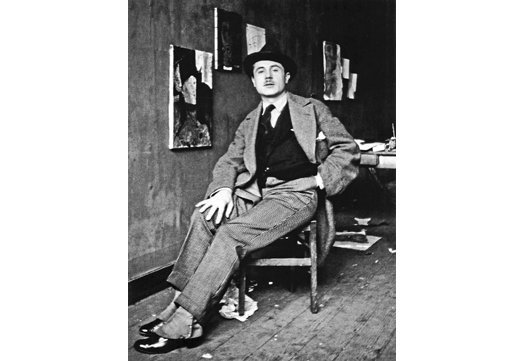

Among the habitués of the Rotonde was Ossip Zadkine, son of a Russian university professor who left Smolensk at the age of sixteen to study art in London, became a sculptor, and moved into La Ruche. He met Modigliani in the autumn after the latter returned from Livorno. Modigliani was wearing a handsome gray velvet suit and the sculptor took immediate notice of the leonine head, the distinctive features, high forehead, alabaster skin, and shining, jet-black hair. Modigliani “looked like a young god disguised as a workman out in his Sunday best.” Zadkine, mentally modeling, noticed that his “clean-shaven chin had a small cleft in it.” Modigliani’s smile was delightful, and he began talking immediately about sculpture and the advantage of direct carving in stone. They first met on the boulevard Saint-Michel and again at the Rotonde. Modigliani had left his canvases somewhere at the Cité Falguière and his sculptures were back in the old greenhouse he called a studio at 216 boulevard Raspail. He invited Zadkine to come and see them.

Zadkine explained that an alley that no longer exists (this comment was made in 1930) led into the back garden of 216. In those days two or three artists’ studios were lined up against a wall. There was a piece of open ground behind them, and overhead a few trees threw their black branches protectively over the vulnerable glass roofs.

Ossip Zadkine posing with his work, 1929 (image credit 9.2)

“Modigliani’s studio was a glass box. As I approached I saw him lying on a tiny bed. His fine velvet suit floated forlornly in a wild but frozen sea and waited for him to awaken.” All around the walls Modigliani had pinned up dozens of drawings, “like so many white horses in a movie frame of a stormy sea that has been stopped for an instant,” Zadkine continued. The drawings also fascinated him; a breeze coming through an open window stirred the large white sheets of paper, which were attached by a single pin, and “one would have thought wings were beating over the sprawled painter,” so still and silent that he looked as if he had drowned.

Once aroused Modigliani showed Zadkine his perfectly oval stone heads, “on the side of which the nose jutted out like an arrow towards the mouth.” Such a lifestyle would not have surprised the visitor, who was also living in similarly uncomfortable quarters. They were so cramped that the wonder was, Zadkine’s friends said, that between his sculptures and an enormous Great Dane, there was any room left for him. “Zadkine, at this period, wore a Russian smock and had his hair cut à la Russe and fringed over the forehead, which gave him a startling resemblance to his own images in wood.” Zadkine understood Modigliani better than most and knew he would never explain what he was doing. “His only response to my comments as a professional sculptor was a pleased laugh which echoed through the shadows of the lean-to he used for an outside studio.”

They were united in all the ways they had invented of managing to eat without paying, “because he quickly blew the money that came from Livorno and I myself, by the twentieth of each month, had spent the advance my father sent me from Smolensk.” By common consent they would walk to the corner of the boulevards Montparnasse and Raspail, the center of life in Montparnasse, otherwise known as the Carrefour Vavin, and sit down at a café terrace. There they would patiently wait “like fishermen, for an old friend to rescue us with a loan of three francs so we could eat at Rosalie’s.” If not they went to Rosalie’s anyway, endured her lectures, and perhaps Modigliani forced another drawing on her that ended up in the cellar.

Several reasons have been given for Modigliani’s eventual decision to return to painting. It is said that the dust from stonecutting was too damaging for his lungs and the work too arduous; both are plausible. It is also thought he was convinced of the relative ease of selling an easel painting compared to whatever he might create in stone, which was much more likely to be misunderstood, took longer to make, and cost more. This is probably also true. One wonders if there was a further reason. In terms of exhibiting his sculptures, Modigliani’s big opportunity came the year before, when seven heads went on view in the Cubist gallery at the Salon d’Automne exhibition of 1912. A photograph of the room in which they were shown was published in L’Illustration and two thumbnail pictures of his heads in Commoedia Illustré (Paris). That was a great piece of luck but in other ways his work was being passed over by bigger shows, that year of 1912, in London, Cologne, and Munich, displaying the latest movements in art. Then an even greater opportunity presented itself. Arthur B. Davies and Walt Kuhn, two American artists, were planning an ambitious international exhibition in New York, traveling widely in Europe in 1912 looking for established and rising talents to exhibit at the 69th Regiment Armory the following year. A crowd of four thousand people attended the opening night of the exhibition, technically the International Exhibition of Modern Art, February–March 1913, soon known as the Armory Show and a historic event: the introduction of modern art in America. There were over one thousand paintings, sculptures, and examples of decorative arts, both American and European. The European painting schools, Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, Fauvist, Cubist, and Symbolist, were particularly well represented. There were Cézanne and Matisse, Picasso, Braque and Léger, Redon and Seurat, van Gogh and Gauguin, Kandinsky, Picabia, Dufy, Derain,…The list went on and on. Nobody had seen anything like it, and comments, criticisms, and caricatures filled the newspapers for months. “Art students burned … Matisse in effigy, violent episodes occurred in the schools,” and when the show moved to Chicago, it was investigated by the Vice Commission “upon the complaint of an outraged guardian of morals.”

There was no doubt in the daring, ability, and freedom to reinvent, and the years 1910–1913 “were the heroic period in which the most astonishing innovations had occurred; it was then that the basic types of the art of the next forty years were created,” the art historian Meyer Schapiro wrote in Modern Art. “About 1913 painters, writers, musicians and architects felt themselves to be at an epochal turning-point corresponding to an equally decisive transition in philosophical thought … The world of art had never known so keen an appetite for action, a kind of militancy that gave to cultural life the quality of a revolutionary movement or the beginnings of a new religion.”

Compared to the enormous range of paintings shown—Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase was another work singled out for praise or derision—European sculpture was relatively poorly represented. There were works by Rodin. Alexander Archipenko, three years younger than Modigliani, was invited and showed a cement torso, Salomé, 1910. Constantin Brancusi, eight years Modigliani’s senior, was beginning to become known and the year before had sold his first work to an American collector, Agnes Meyer. This “arch-modern,” as Schapiro called him, showed five works. Among them was the stylized head of a woman, resting on one ear, called Sleeping Muse. Another was a highly abstracted bust, Mademoiselle de Pologany, in white marble. This particular work was compared to “a hard-boiled egg balanced on a cube of sugar,” and his works caused almost as much of a furor as Duchamp’s descending nude. But when Brancusi’s work was shown that same year in the Salon of the Allied Artists Association in London, the critic Roger Fry wrote that the sculptors were “the most remarkable in the show.” Brancusi was on his way.

Modigliani, by contrast, had not been invited. Unlike other artists he had as yet no dealer and there were no Modigliani heads on view in shop windows. True, but Brancusi had been his mentor, and a close friend. In 1912–13 he was storing one of Modigliani’s heads in his studio, as we know from the latter’s letter to Paul Alexandre. Did he put in a word for his friend? Did he even try? Zadkine said, “Little by little the sculptor in Modigliani was dying.”

Some time afterward Zadkine, visiting the boulevard Raspail studio, was saddened to see abandoned stone heads, “outside, unfinished, bathing in the dirt of a Parisian courtyard and merging with the glorious dust … A large stone statue, the only one he had carved, lay with its face and belly towards the grey sky.” Of the wreckage left behind of Modigliani’s dreams of being a sculptor, some twenty-seven works have survived. Seventeen are in museums, among them the Museum of Modern Art and the Guggenheim in New York, the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris, Philadelphia Museum, and the Tate and the National Gallery of Art in London. The remaining ten are privately owned. In June 2010, one of these, a sculpted stone head owned by Gaston Lévy, a French businessman, sold at Christie’s in London for $52.8 million (see color illustration).

Picasso on the Place Ravignan, 1904 (image credit 9.3)

Although Cubism, the most important new movement in art just then, would determine much of the painting and sculpture in the future, its main proponents, Picasso and Braque, were poorly represented at the Armory Show. This was not as crucial for Picasso as it had been for Modigliani. He was already on his way critically and financially and, in 1912, was living in his smart new apartment with a new lover, Eva. Fernande Olivier, who had been Picasso’s mistress when Modigliani arrived in Montmartre, met Modigliani at one of the cheap restaurants where they could all eat for ninety centimes on credit, and that would include a small glass of something to finish the meal, “often poured by the patron himself.” In those early days Modigliani “was young and strong and you couldn’t take your eyes off his beautiful Roman head with its absolutely perfect features,” she wrote. “At that time he was living … in one of the studios on the bank of the gloomy old reservoir. This was before his vie maudite in Montparnasse, and, despite reports to the contrary, Picasso liked him a lot. How could any of us have failed to be captivated by an artist who was so charming and so kind and generous in all his dealings with his friends?”

The establishment of artists’ suppliers, Lucien Lefebvre-Foinet on the rue Vavin (image credit 9.4)

It was easy to be friendly in the old days when everyone was poor and unknown, drinking cheap wine together, indulging in hashish, and railing against the ignorance of dealers. It was something else when someone like Picasso shot to prominence; Modigliani could not help measuring his efforts against those of the clever Spaniard and finding them wanting. Modigliani also believed Picasso was decades ahead of the rest of them. He was so imaginative, so creative, and so successful. But he was tricky, almost impossible to know, and his reputation for ironic comment, already far advanced, contained a certain cruel humor. One never knew whether it would be turned on one personally. On the other hand he was a natural leader around whom others congregated. He just seemed to know. It was useful to be somewhere on the fringe if only because Picasso’s hospitality was legendary and there would always be a bowl of macaroni for the visitor or even a cutlet. If nothing else. But there was more.

Modigliani resolutely refused to follow Picasso and Braque into Cubism, but there was no doubt he was very much influenced by Picasso’s work and, as the comment suggests, measured his own efforts against it. Pierre Daix, an authority on Picasso, believes Modigliani witnessed the transformation the former’s work underwent in his Portrait of Gertrude Stein, painted just after they met. The original work underwent a radical revision. Picasso “reduces her face to a mask, to contrasts of volume lacking any detail of either identification or psychological expression. That summer, anticipating Matisse, Picasso was the first to take amplification and formal purification to such an extreme. And the faces of all his figure-paintings of the period display a similar reduction to essentials, to structure. Was this what struck Modigliani?”

Daix suggests that in subsequent paintings, particularly Woman’s Head with Beauty Spot, La Petite Jeanne, and The Amazon, Modigliani is experimenting with a similar masklike stylization and geometrical emphasis. The two men certainly had parallel interests, not just their fascination with Negro art. Picasso painted his large canvas Family of Saltimbanques in 1905 which Daix believes Modigliani must have seen since it was in his studio for the next three years. In due course Modigliani had portrayed himself similarly, as a traveling player, using the identical palette that Picasso had used: blue-greens, shades of brown, and oranges. That was in 1915, and by coincidence or design, Modigliani painted a portrait of Picasso that same year. It is a curious picture. The paint is almost scrawled across the canvas in a furious fashion, unlike Modigliani’s carefully developing style. The subject’s penetrating stare is masked, the mouth is small and set, and the expression is secretive, almost cunning. The word “savoir,” knowledge, learning, or “to know” has been appended. Restellini suggests that this perhaps refers to Maud Dale’s belief in Picasso as a visionary. Was that really meant as a compliment or, as Billy Klüver believed, “an ironic comment about the guy who knows it all?” If Modigliani wanted to remain true to his own vision he would have to, and did, keep a safe psychological distance from this powerful, perhaps even artistically stultifying personality. When asked to what “ism” he belonged and in what manner he painted, he would always reply, “Modigliani.” But for an artist to keep his ideas, even his techniques, a secret was well understood. Everyone went to buy paints and equipment from Lefebvre-Foinet, a family of chemists and artists’ suppliers in business since 1872, partly because of their astute awareness that their role was akin to the confessional. Every artist wanted to learn secrets about pigments and techniques that would give him or her an advantage over the rest. So if an artist arrived to consult Lefebvre-Foinet, usually in the lunch hour when everyone else was eating, and if by chance someone else arrived, Lefebvre-Foinet had provided a discreet exit so that the two would never meet.

There was rivalry but also antagonism to at least some degree. It seems likely that Modigliani, ever alert to signs of anti-Semitism, had overheard a certain unkind remark from Picasso. It is claimed—the author is not cited—that in the days when Picasso was poor and Modigliani briefly had some money, Modigliani saw the former passing by his café table, sized up the situation, and offered a loan of five francs. Picasso took the money gratefully. In due course, the situation being reversed, Picasso called on Modigliani one day to return the favor. He presented him with a one-hundred-franc bill. As Picasso was leaving Modigliani remarked that he owed him some change but would not give him any, because “I have to remember I’m a Jew.”

Another story concerns one evening in 1917. Picasso, unable to sleep, decided to paint something. Looking through his collection for a fresh piece of canvas, and finding none, he decided to use a painting acquired from Modigliani. He could have chosen to paint on the reverse, which was an almost universal solution. But that had a certain symbolism Picasso would have automatically rejected. Instead, he painted a still life of his own on top: a guitar, a bottle of port, some sheet music, a glass, and some rope. He evidently felt the urge to obliterate the work of someone with whom he was, obscurely or otherwise, in competition.

A further incident bears out this possibility. At the end of World War II, the art historian Kenneth Clark was lunching with a mutual friend in Paris; Picasso was one of the guests. Lord Clark had brought, as a gift for his hostess, the first book ever published on the sculpture of his great friend Henry Moore. “Picasso seized on it in a mood of derision,” Clark wrote. “At first he was satisfied: ‘C’est bien. Il fait le Picasso. C’est très bien.’…But after a few pages he became much worried.” Picasso left the table and took the book over to a far corner of the room. For the rest of the meal, he sat there turning the pages in silence, “like an old monkey that had got hold of a tin he can’t open.”

In the years to come Henri Cartier-Bresson took a photograph of Picasso’s studio on the rue des Grands Augustins in Paris. By then—it was 1942—Modigliani’s work had become well known. The picture shows one of Modigliani’s paintings, a young girl with brown hair, propped beside the great man’s canvases and sculptures.

Fernande Olivier’s reference to Modigliani’s move to Montparnasse as the start of his “vie maudite” (cursed life) reflects a view that, over the decades, has hardened into a certainty. It is axiomatic that Modigliani was a brilliant young artist who ruined his health and died prematurely from drugs and drink. As has been noted, even authors who are aware that he had tuberculosis take the same similarly dismissive attitude. The addiction showed the extent of his self-destructiveness. We judge from the context of our own age, when tuberculosis is curable, rather than from his, when it was not; that dread disease has faded into the background reserved for forgotten scourges like leprosy and the Black Death.

This version is based on a tragic misconception, but it is, unfortunately, one that Modigliani deliberately cultivated. A key to this is contained in his mother’s diary, written four years after his death, in 1924. Reading between the lines, she provides the clue. Dedo did not want anyone to know—she used the verb “to flaunt, show off, make a point of”—the terrible shadow under which he was living. Only his closest friends knew he had tuberculosis, for the reason that, if such a fact had been known, he would have been avoided, if not shunned by everyone. He had to pretend. Nothing had changed since the days when Chopin’s and Keats’s landlords had burned the furniture after they moved out. If anything, matters had grown worse because, in 1882, Robert Koch famously demonstrated that tuberculosis was a bacillus and easily transmissible. This medical discovery coincided with the fact that, by 1900, tuberculosis was the leading cause of death in France. In the 1890s the French government mounted what was called a “War on Tuberculosis,” and an international congress was held in Paris in 1905, just before Modigliani arrived, to look for a cure. David S. Barnes, author of an invaluable study of tuberculosis in nineteenth-century France, wrote, “Around 1900 tuberculosis was a national scourge, highly contagious, lurking around every corner and symptomatic of moral decay.”

Ordinary people were naturally terrified, often irrationally. Barnes tells the story of a maid who developed bronchitis, so alarming her employers that she was moved out of the house and into lodgings. When she then developed unmistakable signs of tuberculosis she was fired. “Fleeing to the countryside, where her prospects of recovery might have been greater, she sought refuge with her sister. There were young children in the household, however, and the sister refused to have her. The young woman’s last resort was the hospital, but even there, the doors were closed to her, because all of the beds were full.” Studies soon demonstrated the obvious: that the poorest areas of Paris had the worst infections. When an outbreak of bubonic plague occurred in one of those areas, called “îlots insalubres” (unsanitary blocks), the offending buildings around the rue Championnet in the seventeenth arrondissement were demolished. Voices were soon raised demanding that all the îlots insalubres be torn down. Weekly disinfection of buildings where there was an outbreak was mandatory. Voices were raised requiring doctors to identify tubercular patients so that they could be isolated. Everyone else’s health was at risk.

The fact that doctors had no cures did not prevent them from asserting that they had found the cure. The time-honored methods of bloodletting and starvation diets, which further weakened Keats, might have been over, but their replacements were useless, or worse: goat’s milk, cod liver oil, lichen, antimony, tannic acid, creosote, arsenic, or the fumes from hot tar. Modigliani knew all about that. Doctors had been experimenting on his suffering body since he was sixteen. They had given him up for dead. He wanted nothing to do with them.

Accounts suggest that, from about 1914 on, Modigliani’s intake of alcohol increased. Seen from the perspective of his affliction, this suggests that his symptoms had worsened; the reason is not hard to find. As spitting was considered tantamount to involuntary manslaughter, the urge to spit and cough had to be suppressed. Opium, usually taken in a preparation called laudanum, was the most effective antispasmodic and was legal, along with morphine and heroin. Failing these, alcohol was the remedy of choice. Cognac, brandy, and whiskey were preferred, but wine would do. The consumptive took a small sip here, another sip there, whenever he or she felt a cough coming. At all costs he must avoid bringing up “a fawn coloured mixture” of blood and phlegm, as Keats did, or spattering his handkerchief with blood—much less choke on a violent hemorrhage. It was primitive self-medication but effective.

Friends attest to the fact that the moment Modigliani arrived at a café he wanted a drink. Nobody mentions spitting or coughing, which indicates a secret successfully kept. People did notice that he always seemed to have hashish with him. That was further proof of his moral decay. For Modigliani (the born actor) nothing was easier than to feign an addiction he did not have, at least at first, in order to conceal a disease that was going to kill him; better to exasperate than to be avoided and shunned. Perhaps only Picasso, that shrewd observer, suspected the truth. “It’s very strange,” he said, “one never sees Modigliani drunk on the boulevard Saint-Denis (where no one ever went), but always at the corner of the boulevards Montparnasse and Raspail!”—where he was sure of an audience.

Modigliani, center, at the Dôme with Adolphe Basler during World War I (image credit 9.5)

And if he rapidly became drunk, perhaps a moment came when the intoxication, feigned for so long, became a reality. Or perhaps it was just one more stunt when he began to yell, break glasses, take off his clothes, and insult the waiters. When you are thrown out on your ear, do you have to pay the bill? People began to dread the sight of him coming up the street carrying his eternal blue folio of drawings, trying to sell them for the price of a drink. Hamnett wrote, “Picasso and the really good artists thought him very talented … but the majority of people in the Quarter thought of him only as a perfect nuisance.” Basler wrote, “He was the scourge of the bistros. His friends, used to his excesses, forgave him, but the landlords and waiters, who hailed from a different social stratum … treated him like a common drunk.” He might even occasionally bang on his chest and say, “ ‘Oh, I know I’m done for!’ ” and no one took him seriously. This, then, was the explanation for the puzzle I encountered when I set out to understand his life, and it changed everything. Here was no shambling drunk but a man on a desperate mission, running out of time and calculating what he had to do in order to go on working and concealing his secret for however long remained. He was gambling, and willing to take the consequences. It must have been a courageous and lonely masquerade. At the same time he was launching himself on the most successful and productive period of his career.

“[M]any tuberculous individuals have dazzled the world by the splendor of their emotional and intellectual gifts and by the passionate energy with which they exploited their frail bodies and their few years of life in order to overcome the limitations of disease,” René and Jean Dubos wrote in The White Plague. The poet Sidney Lanier used periods of relative health to write feverishly, feeling that his mind was “beating like the heart of haste.” Another poet, Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s feelings of almost unbearable excitement seemed like “a butterfly within, fluttering for release.” John Addington Symonds, who wrote that tuberculosis gave him “a wonderful Indian summer of experience,” also felt the passion to create. “For most sensitive temperaments,” The White Plague’s authors wrote, “artistic expression is a kind of bloodletting, and Symonds spoke endlessly of the relief from his miseries that he found through writing.”

Guillaume Chéron, one of Modigliani’s dealers, as seen by the artist, 1915 (image credit 9.6)

Modigliani also had another, particular reason for celebration: he had finally found a dealer. He was Guillaume Chéron on the rue la Boétie, a small, round, fat man who is portrayed by Modigliani with a bulbous nose above what passes for a moustache. Chéron began life as a bookmaker and wine merchant in the south of France and transferred to pictures after he married the daughter of Devambez, a well-known dealer, and moved to Paris. Chéron knew nothing about art, and most memoirists paint him as boorish as well as ignorant. But he needed clients, realized the importance of publicity, and sent out booklets extolling the virtues of buying art as a financial investment. All that Chéron required were paintings, as cheap as possible. Those were the days when dealers collected stables of artists and paid daily stipends to get the work. Modigliani received ten francs a day. Chéron provided a studio, paints, brushes, canvas, a model, and the necessary bottle of brandy. The studio was in the basement, leading to several lurid accounts of Modigliani’s incarceration in a dungeon with a single window, locked in like Utrillo until he had produced a painting. Since the “basement” also contained a dining room where Chéron and guests lunched every day, the account seems as fanciful as most of the other reminiscences about Modigliani. He certainly did not complain about his quarters. He was absolutely delighted to have a job. “Now I’m a paid worker on a salary,” he told his friends. He and Chéron soon parted company, which turned out to be a blessing in disguise.

Max Jacob, one of the many fascinating characters in the circle of Montparnasse in those days, had arrived in Modigliani’s life. John Richardson wrote, “The pale, thin gnome with strange, piercing eyes … was a Frenchman—brilliant, quirkish, perverse—with whom [Picasso] found instant rapport…[H]e was infinitely perceptive about art as well as literature and an encylopedia of erudition—as at home in the arcane depths of mysticism as in the shallows of l’art populaire. He was also very, very funny.” Jacob, a poet, artist, writer, and art critic, knew and liked Modigliani, and the sentiment was returned. Jacob had studied philosophy, could recite poetry with as much confidence as Modigliani, was addicted to ether and henbane, and was an alchemist. He had introduced Picasso to the Tarot and probably did the same for Modigliani. He was also adept at palmistry and famously had read Picasso’s hand and perhaps Modigliani’s as well, though there is no record of this. But his main gift seems to have been as a facilitator, with a vast network of friends. Hearing that Modigliani and Chéron had parted ways, Jacob had an inspired idea: he would introduce him to Paul Guillaume.

Like Jacob, Guillaume came from a modest background and, also like Jacob, was born with an innate aesthetic sense, rising like a meteor from an entry-level job as a clerk in a rubber-importing company to a collector of African statues and then an expert on primitive art. He was still only in his early twenties. On the other hand he had met Apollinaire, who immediately sensed his unusual abilities and introduced him to the world of artists and sculptors. Most of them were looking, as was Modigliani, for someone who instinctively appreciated and understood their work and had the wit to promote it. In that respect Guillaume was heaven sent. Aspiring art dealers usually started business in a modest way in the rue de Seine on the Left Bank with the goal of eventually reaching wealthier clients on the Right Bank. Guillaume, who did not have any time to waste, started in the rue de Miromesnil, “a neighborhood dominated by the opulent, historic, institutional galleries,” Restellini wrote. It was the maddest folly from a business viewpoint, since artists like Picasso, Matisse, and Derain had already found their dealers, but for unknowns it was an enormous piece of luck. Somehow Jacob, like Apollinaire, was convinced that Guillaume would become famous, as indeed happened with remarkable suddenness, and he decided to introduce the two men. The trick would be to have Guillaume meet Modigliani as if by accident. There are conflicting versions of this story, but they agree on some details. Jacob set the scene with care. He had a date to meet Guillaume one afternoon at the Dôme. Modigliani, as agreed, would arrive ahead of them and make a show of passing his drawings around. His table would be nearby. Jacob was convinced that Guillaume would soon “discover” him.

All of it happened as Jacob planned. Guillaume drifted over to Modigliani’s table, liked the drawings, and sat down. From here the versions differ. The first came from Charles Beadle, one half of the “Charles Douglas” nom de plume of the writers of Artist Quarter. Rose describes him as a “down-at-heel English journalist” who collected mostly “scurrilous gossip and half-truths,” often the passages most quoted from the book. By accident or design, in these stories Modigliani is invariably seen in a poor light. So in this version, when asked if he had any paintings to show, Modigliani curtly said he did not. No doubt Modigliani thought of himself as a sculptor, but after having gone to all the trouble to stage a rendez-vous it is hardly likely that he would have brusquely rejected the invitation he had been angling for. The second version is more likely. When Guillaume asked the same question Modigliani, who perhaps had been hoping to be asked about sculpture, nevertheless admitted that he did paint “a bit.” He complained to Jacob about it afterward. But he did accept the invitation and Guillaume did, indeed, become his new agent.

Like Derain and Giorgio de Chirico, whom Guillaume also represented, Modigliani painted several portraits of his dealer. Guillaume, who dressed with fastidious attention to detail, was as short as Modigliani but not as good-looking. The proportions of his face were against him—cheekbones too wide, forehead much too low—and he had a certain humorless habit of parting his hair strictly in the middle and plastering it down, something that may have made him look older but did nothing to correct the imbalance. He took to wearing hats with sizable crowns, which solved the problem of proportions, and two of Modigliani’s portraits show him hatted. On a portrait painted in 1915 Modigliani has appended “Novo Piloto,” and that was literally true. Modigliani desperately needed a guiding hand along with the publicity only a clever dealer could provide. A year later, Guillaume is still wearing a hat and an arm rests negligently along the back of his chair. A right hand is visible, and just below it, Modigliani has signed his name. Did he feel he was under Guillaume’s thumb? Was he being sufficiently grateful? An article written by Guillaume some months after Modigliani’s death in 1920 offers some clues.

“Because he was very poor and got drunk whenever he could, (Modigliani) was despised for a long time,” Guillaume wrote, “even among artists, where certain forms of prejudice are more prevalent than is generally believed … He was shy and refined—a gentleman. But his clothes did not reflect this, and if someone happened to offer him charity, he would become terribly annoyed.” Who could forget his “strange habit of dressing like a beggar” that nevertheless “gave him a certain elegance, a distinction—nobility in the style of Milord d’Arsouille that was astonishing and sometimes frightening. One only had to hear him pompously reciting Dante in front of the Rotonde, after brasseries closed, deaf to the insults of the waiters, indifferent to the rain that soaked him to the bone.”

Paul Guillaume, the dealer who put Modigliani on the map, 1915 (image credit 9.7)

To think, only six years before, Modigliani had a hard time selling his drawings for fifty centimes or one franc. “No one will deny, I hope, that this sad state of affairs came to an end after he met me. Nor that I was the only person to provide him with some comfort from that time onwards.” There were plenty of people around nowadays, Guillaume commented with some asperity, to find his work important now that they no longer had to face general ridicule.

Guillaume might have added, but did not, that Modigliani was not always the easiest person to deal with, quirky, full of changing moods, and quick to take offense. How delightful Modigliani could be when he was not drunk, Jacob was said to have remarked. “He could be a charming companion, laugh like a child, and be lyrical in translating Dante, making one love and understand him. He was naturally erudite, a good debater on art and philosophy, amiable and courteous. That was his real nature, but nevertheless he was just as often crazily irritable, sensitive, and annoyed for some reason he didn’t know himself.” That, too, was part of the general chorus: Modigliani is angry, but he does not know why.

There are references to what Jacob Epstein called Modigliani’s predilection for “engueuling,” i.e., violent abuse of someone or something that aroused indignation and rage, though Epstein thought the outburst was usually merited. One never knew when this seemingly lovable personality might become haughty or rude, spiteful, and even hostile. The fact is that such mood changes are to be expected and are common, if not universal, among tuberculosis victims. Keats’s rapid shifts of mood are famously charted in his letters, “where in a moment he can go from self-mockery and brilliant wit to self-analysis to depression or indolence,” Plumly writes. “Always in extreme,” one of his classmates said, “in passions of tears or outrageous fits of laughter.” Keats also suffered from “blue devils,” black moods that periodically overwhelmed him; as for Modigliani, the well-known depressive effects of alcohol would have spiraled him further into despair. It was no coincidence that his laughter often seemed to have a demonic edge. One young student, studying at Dartmouth in the mid-nineteenth century, who was obliged to leave the college when he developed tuberculosis, wrote, “Shackled and oppressed by the most tedious and vexatious complaint that ever cursed human nature, I have been obliged to … relinquish my studies and overthrow and destroy some of my fondest and darling expectations.” Modigliani did not need to put his own feelings down on a page. He carried them in his pocket.

Les Chants de Maldoror (The Songs of Maldoror) was described by André Gide as “something that excites me to the point of delirium,” and as a work of “furious and unexpected originality by a mad genius.” Part Gothic fantasy, part serial novel and horror story, Les Chants de Maldoror is not a song or even a poem but a kind of interior monologue. Maldoror is “a demonic figure who hates God and mankind,” Ronald Meyer wrote. Edmond Jaloux called it “a world with a tragic grandeur, a world that is closed, impermeable, incommunicable”; a Divine Comedy “written by an adolescent of extraordinary intuition, full of darkness and punishment, and centripetal gloom.” In short, Octavio Paz observed, its author “was the poet who discovered the form in which to express psychic explosion.”

Les Chants de Maldoror’s author was Isidore Ducasse, who styled himself as the Comte de Lautréamont. Ducasse, born in 1846, was the only child of a French couple living in Uruguay, where his father was an officer in the French consulate in Montevideo. He never knew his mother; she died a few months after he was born. He was sent to be educated in France, where his classmates described him as “a tall thin young man, slightly round-shouldered, with a pale complexion, long hair falling across his forehead … At school we reckoned him an odd, dreamy character.”

After school Ducasse moved to Paris to become a poet. This first, rambling work was published in 1869 but was termed too controversial for general release and remained more or less unknown until it was rediscovered and republished in 1890. Modigliani seems to have found a copy in about 1910 and reacted as Gide had done: it was a life-changing experience. He memorized whole paragraphs and was willing to be parted from it only briefly by people like Paul Alexandre, who promised to give it back.

Ducasse also seemed to have had a Surrealistic premonition a good fifty years before anybody knew enough to give the movement a name. His delirious imagination, his grotesque imagery, his demonstration of what could be created once the mind had dispensed with proper moral feeling, looked more than prescient, but almost uncanny, as if he had written the first Surrealist Manifesto in a visionary dream. In particular, images like “the chance meeting on a dissecting-table of a sewing machine and an umbrella” gave André Breton, the poet and the movement’s chief theoretician, a jolt from which he never recovered. When Breton discovered Maldoror in a Belgian library (a decade after Modigliani had), and in the days before photocopying machines, he did it the singular honor of copying it out by hand—it ran to eighty thousand words. Another early Surrealist, Salvador Dalí, finding in Les Chants de Maldoror the most perfect possible example of his “paranoic-critical” method, devoted forty etchings to illustrating passages from the book. They are among the most delicately conceived and imaginative of his works.

What is almost never pointed out about Ducasse, at a time when the illness was as taboo as AIDS is now, is that he was yet another victim of tuberculosis. At least some of his pages were written at the very end of his life, when whatever was feigned about his feverish state had become all too real. He died a year after it was published, in 1870, at the age of twenty-four.

Like Modigliani, Ducasse “sings” what he did not dare to reveal: that he was very ill and probably dying. The clues are clear enough. First Canto: “Feeling I would fall, I leaned against a ruined wall, and read: ‘Here lies a youth who died of consumption. You know why. Do not pray for him.’ ”

Second Canto: “It is not enough for the army of physical and spiritual sufferings that surround us to have been born: the secret of our tattered destiny has not been vouchsafed us. I know him, the Omnipotent … I have seen the Creator, spurring on his needless cruelty, setting alight conflagrations in which old people and children perished! It is not I who start the attack; it is he who forces me to spin him like a top, with a steel-pronged whip … My frightful zest … feeds on the crazed nightmares which rack my fits of sleeplessness.” Maldoror, a name probably derived from mal d’aurore, a bad dawn, is being taken for a madman, “who seemed not to concern himself with the good or ill of present-day life, and wandered haphazardly,…his face horribly dead, hair standing on end, and arms—as though seeking there the bloody prey of hope.” He is “staggering like a drunkard through life’s dark catacombs.”

Fifth Canto: His body is no more than “a breathing corpse,” and his bed is a coffin. His only pleasure is making others suffer in agony as he himself is being tormented. It all begins to sound like “engueuling” and also like Eugénie’s poem “Fierce Wish,” in which she proposes to set fire to her neighbor’s barn and burn his child alive: a frustrated rage and resentment that turns on life itself. Small wonder that Modigliani memorized page after page. He could hardly avoid seeing himself in the same light, as one more victim of a malignant fate. In 1913 he, offering a drawing of a caryatid to a friend, added the dedication: “Maldoror to Madame.”

One spring day in 1914 Alberto Magnelli, an Italian artist four years Modigliani’s junior, who happened to be in Paris studying Cubism, was strolling along the boulevard Montparnasse in a westerly direction toward the railway station. It was a beautiful morning and he was thinking of other things when he realized that the conductor of a tram, also traveling in his direction, was ringing his bell violently and simultaneously applying his brakes with a great screeching noise. He looked up and saw a man on the opposite sidewalk crossing the street in front of the tram, walking like an automaton straight toward it. He was bound to be hit. With a start, Magnelli realized it was Modigliani.

In a flash Magnelli had sprinted across the street and flung himself at Modigliani, whose eyes looked glassy and enormous. He wrote, “I do not know how I managed to get in front of him in time.” He was so close to the tram that it scraped him as it passed. As for Modigliani, he had been knocked to the ground and seemed, at that moment, to have come to his senses. He was helped over to the sidewalk and the nearest café table, which happened to be at the Rotonde. Magnelli ordered a round of drinks. About his narrow escape from death, Modigliani did not say a word.