Beatrice

Have you noticed that life, real honest-to-goodness life, with murders and catastrophes and fabulous inheritances, happens almost exclusively in the newspapers?

—JEAN ANOUILH, The Rehearsal

BEATRICE HASTINGS, who met Modigliani in the summer of 1914 and with whom he fell madly in love, was a poet, journalist, editor, and novelist, and an invaluable witness to one of the most important periods of his life. In contrast to her lover, for whom putting any words on paper was like pulling teeth, she dashed off a weekly column about life in Paris: anything and nothing. That included references to him, their friends, conversations, and daily life together that are only sporadically disguised.

Yet even she has said different things at different times, making the separation of truth from fiction almost as difficult as it is in any other aspect of Modigliani’s life. One version given for the way they met has been quoted often. In it she said she met him at the Rotonde and was repelled. He reeked of brandy and hashish and needed a shave; she thought he was a pig. But when they next met he was clean, neat, shaved, and sober. “Raised his cap with a pretty gesture, blushed to the eyes, and asked me to come see his work.” He might be “a pearl” after all.

Modigliani, about the time he met Beatrice Hastings (image credit 10.1)

The “pig” versus “pearl” is not only suspect—a comment made, perhaps, long after they had broken up—but hardly reflects the truth about their relationship or does justice to the subtle evasions of this author whose biography by Stephen Gray, Beatrice Hastings: A Literary Life, runs to seven hundred pages. Born in South Africa of British parents, she was as much of a phenomenon in her own right as Akhmatova was in hers, a New Woman emerging from the detritus of the Victorian Age, abandoning her corsets, shortening her skirts, smoking, drinking, and taking lovers. From the start this softly pretty girl with a halo of brown hair and an uncompromising gaze seemed able to épater les bourgeois in a way that the women in Modigliani’s family, including his sister, could hardly dream of. First of all, she married a boxer, probably while she was still a teenager. Shortly afterward she had divorced him and sailed to New York, where she attempted to become a showgirl. This did not last either, and she was soon in London, where she had the good luck to hit upon her rightful career as a journalist, the literary editor of a progressive weekly magazine appropriately titled the New Age. It helped that the magazine’s editor, A. R. Orage, was in love with her. But she was a pearl in her own right, as he discovered, nurturing the talents of Ezra Pound and Katherine Mansfield and the intellectual equal of authors like H. G. Wells, Bernard Shaw, G. K. Chesterton, and Arnold Bennett who graced its pages.

The evidence she herself presents about her first meeting with Modigliani suggests that the truth was more complicated. Along the way several people, including Zadkine and Hamnett, claimed to have introduced them. By 1936 she was annoyed enough to contradict them and herself. She wrote to Douglas Goldring, who subsequently coauthored Artist Quarter, that she met Modigliani before Hamnett arrived in Paris and not at the Rotonde (after all). The real story was in her book, Minnie Pinnikin, an unfinished, semiautographical novel. By 1936 she had written a number of chapters but unfortunately had mislaid it. In those days, “I was Minnie Pinnikin and thought everyone lived in a fairyland as I did.” She was shrugging him off with a lame excuse but it was also true that her typescript had disappeared. Subsequent authors, including Pierre Sichel, assumed it had been lost. Then one day the art historian Kenneth Wayne made a sensational discovery in New York. He was doing research at the Museum of Modern Art in preparation for an exhibition, “Modigliani and the Artists of Montparnasse,” in 2002 at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, and there it was in the William Lieberman Papers. Wayne published the first chapter, which he translated from the French, in the catalog for the show.

The name, Minnie Pinnikin, could well be a reference to Mimi Pinson, the heroine of a novel by Alfred de Musset written in the 1840s. If so, it is a strange one, since the novel tells the story of a grisette who provides “a perfect answer to the physical and emotional needs of lonely, sometimes idle, and often self-centered young bourgeois,” Seigel observes in Bohemian Paris. One would expect that since Minnie Pinnikin represents herself, Hastings would have modeled her heroine on some prominent early feminist. But she always denied being one, among the many curious contradictions of her character. She was not to be labeled. She was simply doing what women had always done, fighting her way to the top with a judicious blend of intelligence, guile, tactics, talent, and charm. And if the price of success included sex she was perfectly willing. It is said that she boasted about how many men she had slept with and kept a running tally of notches on her bedpost. Before she dispensed with corsets, there is a photograph of her in a preposterous hat balanced precariously on an untidy nest of hair. Her tight-fitting jacket clearly shows the outline of her nipples, the kind of absentminded-on-purpose display one rarely sees even in drawings of Toulouse-Lautrec’s prostitutes.

Beatrice Hastings at the turn of the century (image credit 10.2)

In Minnie Pinnikin Modigliani has the name of Pâtredor, or Pinarius, and the first chapter is a description of their meeting. He was “fishing men from the street, swinging them with his long hands. ‘How beautiful he looks this morning!’ It was true he was really beautiful. The sun that danced in his hair leaned forward to look into his eyes.” Then Pâtredor becomes aware of Minnie Pinnikin and drops everything to run after her. “One could tell that they would be married one day, but no one ever mentioned it simply because it was not yet time,” she wrote. They were “still playing the first love games: jumping from hill to hill, traveling the world without stopping anywhere, drinking rivers of hope as big as the Seine.” All of which does not tell us how they met either.

The version that probably comes closest to the truth—which is not saying much—is the one published in the New Age early in June 1914. She had arrived in Paris two or three weeks before and they had already met, but he was probably looking disheveled. They met again at Rosalie’s one evening. A friend whom she does not identify except as “an English bourgeoise” “was satisfied when she saw me wake up from a sulk to be very glad with the bad garçon of a sculptor.” This is obviously Modigliani, though what she means by being awakened, a sulk, or even “to be very glad” is not explained. Her evanescent and coquettish literary style would give some of her columns such a maddening feeling of evasiveness that the wonder is that they were even published, much less read. She continued, “He [referring to Modigliani] has mislaid the last thread of that nutty rig he had recently, and is entirely back in cap, scarf, and corduroy. Rose-Bud was quite shook on the pale and ravishing villain.” Rose-Bud is Rosalie, and almost everyone in Hastings’s columns is disguised in such a way as to be understood by the “in” crowd. But then, she loved disguises, the more the merrier. Born Emily Alice Haigh, she soon became Beatrice Hastings. She wrote her column as Alice Morning and was, at various times, A.M.A., E.H., B.L.H., T.K.L., V.M., T.W., Beatrice Tina, Cyricus, S. Robert West, and on and on.

There was nothing elusive about Modigliani when he was in love. Hastings might couch her feelings in coy fantasies, rolling her eyes and fluttering her Oriental fan; he was all masculine impetuosity. If the stories can be believed, and at least one has the ring of truth to it, he might even make a brazen date with a woman he fancied as her husband or boyfriend sat listening in amazement and disbelief. In the years since Akhmatova, he had taken and dropped as many delectable mistresses as Hastings claimed lovers. But he must have done so with exemplary tact, to judge from the willingness of said ladies to tearfully press him with parting gifts instead of the other way around. In all his dealings with women Modigliani was the conventional southern Italian male, as described by Barzini, pursuing tirelessly and then, particularly if he loved someone, jealous and possessive. Modigliani was also a charming suitor, known to offer books, pass beneath windowsills at night, and rob the graves of funerals for a flower to present with the breakfast café au lait. None of that was necessary in this case. What seeps through the recollections of Zadkine and Hamnett, who certainly saw the two together soon after they met, is what is not being said. Could it be that the onlookers jumped back in alarm, for fear of getting burned, when faced with the conflagration they had unwittingly unleashed, what the French call a “coup de foudre”?

There is no doubt that Modigliani and Hastings had an almost uncanny number of interests in common. Here was the poet he had lost when Akhmatova walked out of his life. Well, unknown poet as yet, but of course she would soon be famous. Her name was Beatrice, that of Dante’s inamorata, another good omen that cannot have escaped his notice. She was a Theosophist, follower of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, in love with painting, sculpture, literature, and music, and a Socialist to boot, following international affairs with almost the same close interest as Emanuele Modigliani did. Garrulous in prose, she tended to be quiet and terse in conversation, practical and predictable unless she was drunk, as she sometimes was. She, too, experimented with drugs. She spoke excellent French and had arrived in Paris to observe and record cultural life. She was recovering from a seven-year affair with Orage and was now thirty-five, five years older than “the sculptor.” She was not short of money, which for a man who could barely support himself, let alone a mistress, must have been a relief. There remained that extra quality, that mysterious magnetism of the body and spirit that can never be accounted for. It just was, and it would be the beginning of a tumultuous two-year affair.

They were meeting on the literal edge of war. At the end of June the heir to the Austrian throne, the Archduke Ferdinand, and his wife had been assassinated by a nineteen-year-old Serbian student at Sarajevo, a seemingly obscure event that set in motion a European conflagration. Austria declared war on Serbia on July 23 and André Gide wrote in his diary, “We are getting ready to enter a long tunnel of blood and darkness.” Jean Jaurès, the left-wing French leader, was dispatched to Brussels on a peacekeeping mission and on his return was shot in the back as he sat in a café. Russia was mobilizing. On August 1, Germany declared war on Russia; two days later, France and Germany were at war. England was about to take part. Gide, in Normandy, took the last civilian train back to Paris. Gris, in the south of France, had been advised to leave. Jean Arp took temporary refuge in the Bateau Lavoir before leaving for Switzerland. Matisse tried to join the military but was turned down. Picasso drove Braque and Derain to Avignon, where they joined their regiments. Within a month the German army would be closing in on Paris, the stock exchange would have moved to Bordeaux, 35,000 Parisian males would be conscripted, and as many inhabitants would have fled. Against this background Alice Morning made bright and inconsequential remarks, at least at the beginning.

Hastings had found an apartment at 55 boulevard du Montparnasse. She had “two rooms and real running water and gas and crowds of chests of drawers and wardrobes, and only sixty-five francs a month. Anyone will know how cheap that is for Montparnasse.” Her concierge was also a gem (she used the word “duck”) and “everything’s very joyful except a large rat which is a shocking thief.” She was living opposite Brancusi, who sang at the top of his voice, and had a view, not of trees, “only ivy and roses, but lovely old red tiles and air and blue sky.” Her Paris—just three streets and a café—was full of gossip, much of it mean-spirited. “People don’t report on each other’s psychological frailties—they try to attack the spirit. Mention whomever you may, someone will tell you that he is finished, from Picasso to my friend the poor poet who has not very well begun. To escape being finished in Montparnasse, the only way is never to begin really.” The “poor poet” reference was to Max Jacob, whose unpublished French poems she was translating and sending off to London for publication as examples of the latest trend in French poetry. Jacob was to become the close friend and eyewitness to the relationship, making it curious that he would dismiss Hastings later as “drunken, musical (a pianist), bohemian, elegant, dressed in the manner of the Transvaal and surrounded by a gang of bandits on the fringe of the arts.”

She went to an artists’ ball. “Much laughter, much applause for your frock if it is chic, three hundred people inside and outside the Rotonde, very much alive!” She started to attend the Tuesday poetry readings at the Closerie des Lilas where one could hear the last word in Symbolist verse. She sat in cafés for hours to keep warm, writing her columns beside an empty coffee cup or a glass of “mazagran” (half coffee, half milk). The June rain “stupefied” Paris. Madame Caillaux, wife of the minister of finance, against whom Le Figaro had been waging a scurrilous campaign, shot the editor, who shortly thereafter died. She was now on trial, and opinion was sharply divided about whether she should be sentenced or acquitted. Beatrice, making no bones about her bias, wrote, “Mad women ought merely to be handed over to their families with powers gently to chloroform them if necessary.” Then the New Age author goes into considerable detail about trying to light up a cigarette at another ball—a shocking act for a woman in public—and being surprised that she was herded into a corner by the uniformed attendant (where no one could see her), without any apparent awareness of the contradiction. That was the column (June 18 of 1914) when she opened with the news that “[t]he romantic world seems to have supposed that I kissed the sculptor last week.”

After various hints and transparent disguises, Modigliani appears under his own name early in July. “What beats me is when, for instance, an unsentimental artist like Modigliani” approved of Douanier Rousseau, whom she found “bourgeois, sentimental and rusé.” Modigliani really liked him. Speaking of Modigliani’s stone heads (which she wasn’t), one was standing below a painting by Picasso,

and the contrast between the true thing and the true-to-life thing nearly split me. I would like to buy one of those heads, but I’m sure they cost pounds to make, and the Italian is liable to give you anything you look interested in.

No wonder he is the spoiled child of the quarter, enfant sometimes terrible but always forgiven—half Paris is in morally illegal possession of his designs. “Nothing’s lost!” he says, and bang goes another drawing for two-pence or nothing, while he dreams off to some café to borrow a franc for some more paper! It’s all very New Agey, and, like us, he will have, as an art-dealer said to me, “a very good remember”…He is a very beautiful person to look at, when he is shaven, about twenty-eight, I should think, always either laughing or quarrelling à la Rotonde, which is a furious tongue-duel umpired by a shrug that never forgets the coffee.

He took her around. “You’re only seeing Paris,” he said, referring to the obligatory tour. “Come, leave all these people—let us go and see Par-ee.” They went to the movies and he fell asleep on her shoulder. He “tutoyed” her “infamously.” He told her what to buy. He told her not to fall in love with him. On the other hand, perhaps she should. No, not; it’s no use, he said. The way she looked at him, responsively, reminded him of the gaze of his first statue. They were going everywhere together and eating cheap meals in the right places, which more or less guaranteed instant gossip and contradictory commentary. The writer Charles-Albert Cingria suggested with perfect seriousness, “he abducted her”—but did not explain. On the other hand others believed she had pounced on him. The sculptor Léon Indenbaum considered her to be Modigliani’s “wicked genius.” To Paul Guillaume, the fact that she was five years Modigliani’s senior made him her protégé. It is almost certain that he soon moved in with her and perhaps she paid for a studio as well. At one point, Guillaume says he rented a space at 13 rue Ravignon, and at others, that Hastings did. From the artist’s viewpoint, who paid did not matter, as long as he had a roof over his head and was reasonably sure of his next meal.

Guillaume is a reliable witness, and his suggestion that Hastings played a supportive, if not sheltering, role is persuasive. She had nurtured other artistic careers, after all. Her New Age diary shows, time and again, her concern for the helpless. The routine spectacle of horses being beaten, of injured animals, her tolerance for a thieving rat, even her description of a wasp she was nursing back to health: these incidents demonstrate her response to those in need. And Modigliani was very needy indeed. At the start of her Paris columns she refers indignantly to the misery all around her. “But, you know, it isn’t all gay in Paris. There are horrible things. I find even more insupportable than the fact of a charlatan like Tagore getting the Nobel prize the sight of artists surrounded with all the refinements which money cannot buy, but unable to purchase the materials for their work.”

She made her first trip back to London in July and wrote a column about it. “Modigliani, by the way, was very much [in evidence] when I was coming away. He arrested [stopped] the taxi as it was crossing the Boulevard Montparnasse and implored to be allowed to ride with me … But I didn’t know what to do with him on the station when he fainted loudly against the grubby side of the carriage and all the English stared at me. I had to keep calm because, if I get cross, I can’t remember my French … But all this while the English were staring at me and Modigliani was gasping, ‘Oh, Madame, don’t go!’ ” With war imminent, it would be natural for him to fear he might not see her again. But the episode of fainting—if Hastings does not exaggerate—suggests something more. A few months earlier, Modigliani had, by accident or design, almost walked into the path of a tram. Since then he had found an enthusiastic supporter in this unlikely person, who was taking him up and making him her personal cause. Did he fear what might happen to him if he never saw her again?

It was the week before Austria declared war on Serbia. “Women should have nothing to do with war but to speak against it,” Hastings wrote. Modigliani may have told friends that he volunteered. But his fear of discovery and the fact that, as an Italian citizen, he was still technically neutral, makes that unlikely. In any case, this particular war did not interest him much. His attitude seems, on the face of it, hard to explain, even though, as Kenneth Clark observed, “great artists seldom take any interest in the events of the outside world. They are occupied in realising their own images and achieving formal necessities.” There was a further reason. Giuseppe Emanuele, who kept in close touch and was primarily responsible for supporting Dedo financially all these years, was a pacifist, therefore completely opposed to entering the war. “He was thus a target for the interventionists, becoming one of the most widely detested exponents of what was known as antipatriotic ‘defeatism,’ ” his biographer, Donatella Cherubini, wrote. His view was that “[t]he war had been brought about by the colonialist, protectionist and imperialist aspirations of the European industrial class, which overthrew the existing order in the name of its own interests.” G. E. Modigliani himself wrote, “[W]e are witnessing a war between England and Germany for predominance in Europe.” To think any good would come from it was “mere folly.” If Mené refused to take sides, Dedo would not either. For her part, Beatrice stoutly averred that decent women should also refuse to take part. They were both Socialists. They would sit this one out. Despite the pleas of Orage to stay in England for her own safety, Hastings went back to Paris. She arrived a matter of days before England declared war on Germany.

Paris, as Colin Jones writes in his inimitable history of the city, being closer to the front than any other capital city in Europe, was in the path of immediate danger as soon as war was declared. By early September the Germans had raced through Belgium and were within fifty miles of the capital. General Gallieni, in command, attacked the German advance at the Battle of the Marne, and sounds of the heavy artillery fire could be heard in Paris. At the same time General Goffrey, bringing up the rear, attacked the weak flank of the German advance. That was the moment when Gallieni requisitioned every taxicab in Paris to get four thousand men to the front. Thanks to these efforts the German advance was halted. By Christmas of 1914, the war had become focused on vast networks of trenches stretching from the English Channel to the Swiss frontier.

Having a drink with the troops during World War I (image credit 10.3)

Jones wrote, “Many artisans’ shops and small businesses closed down altogether, while the flight of capital and the relocation of non-combatants out of the city caused a slump in demand for many manufactured goods. Most museums closed and the Grand Palais became a military hospital. In the early years inflation hit very hard … Sugar and coal were the first to be rationed and bread followed.” There was coffee without milk in the cafés, and no croissants for the duration.

The months of what would be called the Siege of Paris became Alice Morning’s, or Minnie Pinnikin’s, or Beatrice Hastings’s, finest hour. The tone of archly frivolous chatter vanished, replaced by a straightforward, sober account of what was happening. Her “Siege Diary,” as she called it, began with some sardines, bad rice, and sixteen eggs in the pantry and that was all. Two days later she could report, “Money is a little easier. I managed to change a 50-franc note after three days’ vain flourishing of it. But prices of things are ruinous.” On about the 5th of August she waited for hours in queues for the required permit to allow her to remain in France but, in the end, left without one. On her way home she bought three pounds of plums, thinking she would make some jam, but “there isn’t a quarter of a pound of sugar left in the district.” Food would become a daily obsession. On August 20 she wrote, “This morning very little food was delivered to the Montparnasse district, and all was snatched up at once. I got some cooked pork for a franc, an awful diet in this heat, but there was not a vegetable or fruit left. One keeps open house these days on bread and cheese … One can’t dine out here where one’s hungry acquaintances are liable to pass by. I tried it once—a very bad half-hour!”

Their circle of friends was dwindling by the day. “People vanish, sometimes without even sending to say goodbye. A windfall in the shape of … Charles Beadle turned up yesterday and we wallowed in a prolonged literary row to get away from the war. But, after all, round we came to it. You couldn’t get away from it, even if at bottom you really had a thought for anything else. It comes closer and closer every day. In vain people ransack themselves to change the conversation, even to telling each other their life-stories. A sudden shout from the street breaks attention. You rush out to get the news.”

Fortifications were going up around Paris and houses and buildings within the military zone were being destroyed. “The first effect of this seems to be an enormous run on fruits and vegetables which, luckily, are flooding the market just now. Everybody except me went today to see the cattle and sheep in the Bois de Boulogne. Thousands, they say, have been brought in from the fields.”

As for the Gare du Lyon, that was overwhelmed with Parisians trying to go south, or anywhere. They arrived, “some sitting bolt upright and clutching the sides of taxis as if to push them along faster,” and all of them immobilized by mountains of luggage: household goods, mattresses, chairs…“One couldn’t help laughing to see the taxis, some with six and seven spanking trunks which the least sense of decency would have left behind, considering the common knowledge that many persons will have to wait a couple of days to get half a seat for the south … The train yesterday went out with people standing all over the corridors.”

Beatrice Hastings, 1918 (image credit 10.4)

There were piteous columns begging for news of relatives in the daily papers—“People seem to have lost each other all over the country”—and another obsession, the course of the war. When Gallieni won the Battle of the Marne, there was a new entry. “We have been waiting all day, more or less feverishly” for the news, she wrote. “Forty kilometres back from Paris. My blessed Montparnasse, we are saved! No cannons coming, no more bombs. Hurray for the Allies! Hurray!!!”

It was an awful sight when Belgian refugees began arriving from the Mons district, “hundreds and hundreds, all wet and muddy, lost and beggared and many sick.” She went to the Gare du Montparnasse, where the Croix Vert was passing out food and drink to the lightly wounded. “The hour was slack when I arrived. There were only about fifty soldiers on the platform—but they were absolutely starving with hunger and cold. The Croix Vert had to send yesterday for doctors and nurses to give aid to some men, including an English officer, who were in danger of dying at the station from exhaustion … While I was there, three or four small convoys came, and I talked with one or two soldiers. All those on the way in were lame, halt or blind, but cheerful under sandwiches and cigarettes.” Nobody talked about the war.

By now Modigliani’s rejection of sculpture in favor of painting was almost complete. There is some evidence for the way he felt about that subject from a conversation he and Beatrice (he called her “Beà”) had over a head she had found in the muddle of his studio and which she insisted on calling brilliant, that first winter of the war. She writes, “I routed out this head from a corner sacred to the rubbish of centuries, and was called stupid for my pains in taking it away … I am told that it was never finished, that it never will be finished, that it is not worth finishing.” But she loved it. “The whole head equably smiles in contemplation of knowledge, of madness, of grace and sensibility, of stupidity, of sensuality, of illusions and disillusions—all locked away as a matter of perpetual meditation … I will never part with it unless it be to a poet; he will find what I find and the unfortunate artist will have no choice as to his immortality.” It would be like Modigliani, faced with disbelieving laughter at his expense, to lose faith in himself, even if a few admirers like Augustus John had paid a stupefying sum for his work. As for Beà, how much he cared about her opinion is unclear, but she concludes by complaining that artists do not appreciate the value of writers, “who control the public and try to bring it to a state of culture which will offer the artists great subject for their work.”

Beatrice Hastings, with her links to influential intellectuals, provided opportunities for other appreciative comments, as Modigliani would soon discover. Thanks to Jacob Epstein, two of Modigliani’s heads were shown in an exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in the summer of 1914, along with work by Epstein himself, Vanessa Bell, Roger Fry, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Mark Gertler, Duncan Grant, Paul Nash, Walter Sickert, and Stanley Spencer, most of them destined to dominate the London scene in the years to come. Then early in 1915, Guillaume pulled his conjuror’s strings to give Modigliani his first showcase in New York. It was two years after the exhibition at the Armory, but never mind. The gallery, called the Modern, was on Fifth Avenue, and Modigliani was handsomely represented with twenty-four works, most of them drawings, but there were also a pastel, a painting, and two stone heads. Sometime in the autumn of 1914 he attracted the interest of a new collector, André Level, who began buying his work, paying between fifteen and sixty francs apiece. When one considers that Hastings had rented her apartment for sixty-five francs a month, the sums begin to look respectable by Modigliani’s modest standards. Other people, including the dressmaker Paul Poiret, began to collect. Because of the war Modigliani’s monthly stipend from Italy had dried up. But he could truthfully tell his mother that his work had begun to sell—at last.

The return to painting had social as well as financial consequences. Basler wrote that Modigliani “was surrounded by an ever-increasing number of admirers from all over the world. Everyone wanted to be portrayed by him.” One of the first was the painter and art collector Frank Burty Haviland, who lived near Picasso in the rue Schoelcher. If only for career reasons this was a smart move. Haviland was at the very heart of the inner artistic circles, he was wealthy (his American forebears had founded an important porcelain factory in Limoges), and he was known to be generous. But for Modigliani, who was incapable of being calculating, there was a genuine friendship with this tall, fair, reserved young man, who was quietly serious about art and as fascinated by African sculpture as he was. The Haviland portrait, which Basler once owned, shows the subject in profile and the style influenced by pointillism. Flavio Fergonzi writes that “the broken and choppy brushstrokes generate a vibrant luminous effect” and the conception “is … strongly indebted to the months that Modigliani spent working on sculpture.”

Modigliani’s second success was a portrait of Diego Rivera, the Mexican artist and revolutionary, husband of Frida Kahlo, who spent some turbulent years in Paris and with whom he briefly shared a studio. Rivera, whom he called the “Mexican cannibal,” had, according to his biographer Patrick Manham, a chronic liver condition which caused periodic fits. One of several preparatory drawings Modigliani composed for his portraits showed that he had witnessed at least one of them, because Rivera’s eyes are rolled up, leaving only the whites visible. The portrait itself, a swirl of off-whites, grays, and charcoal, is as revealing as Picasso’s was noncommittal. The small, pursed, full-lipped, fat man’s mouth, the narrowed eyes, and the enigmatic half smile, executed in a burst of whorls and scribbles, give one an immediate impression of a man as engaging as he was violently unpredictable.

Modigliani’s portrait of Diego Rivera, 1914 (image credit 10.5)

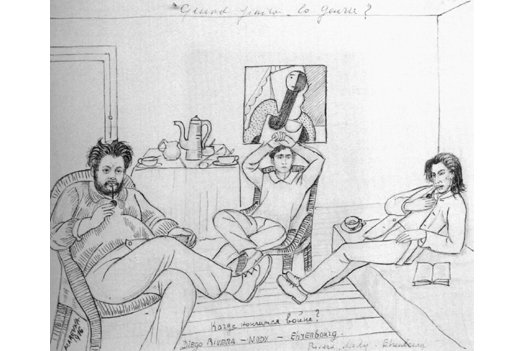

A sketch by Marevna of Rivera, Modigliani, and the writer Ilya Ehrenburg, during World War I (image credit 10.6)

So many friends had left for the war. Paul Alexandre, immediately attached to an infantry battalion as a military doctor, was not released until the general demobilization in 1919. He wrote, “My regiment was wiped out several times before my eyes.” Maurice Drouard, Henri Doucet, and the sculptor Coustillier, all close friends of Alexandre, were killed. Apollinaire, who received a head wound, would die of his injuries. Léger and Braque were wounded and discharged, Jean Metzinger was gassed and Blaise Cendrars, the writer, lost an arm. As for the ever-resourceful Paul Guillaume, he was briefly mobilized and then discharged, opened and closed a couple of galleries, and was back in business by 1915. He had found a new backer, again thanks to the ministrations of Jacob: a wealthy dealer in antiquities named Joseph Altounian. Guillaume, with the field wide open, was full of energy and ideas for promoting the work of painters lucky enough to have attracted his interest.

A dwindling band of artists—mostly foreigners—met each other in the old haunts. “The wartime lack of cohesion and direction in the art world worked to the advantage of those who had been either outside or on the fringes … before the war, creating fresh possibilities and new alliances,” Silver wrote. Basler observed,

Just about every Montparnassian had his portrait drawn or painted by Modigliani. And there were a few who did not clink glasses with him at least once. Everyone liked him—the owner of the hotel in which he lived, his hairdresser, the people in the bistros. They all have pictures by him or pleasant memories of him, be it the female Russian painter Vassilyev, who fed him in her canteen during the war, or all the amicable topers in the quartier, or the little Burgundian sculptor X, the North African painter Z, or the Communist philosopher Rappoport, with whom Modigliani seldom saw eye to eye, or even the policeman who locked him up when he got drunk … Dear old Modigliani could not have dreamed up a better public than the one he had during the war.

The always hospitable cafés, where “we hung about from morning to night,” became virtual living rooms. Marevna wrote,

Where else could we go? Few of us were in the position of [Ilya] Ehrenburg, who lived in a hotel and had heat and hot water during certain hours; but then he earned the right to live like a bourgeois for part of the day by hauling crates and sacks at the [railway] station at night. Most of us were chronically short of coal and gas and had long since fed to the stove all that could be burnt; the water in our studios was frozen. After a night spent shivering under thin blankets, we would rise late and rush to the café, to be greeted by a kind smile and a “Comment ça va, mon petit?”…Then we would warm ourselves with hot coffee … read the news from the front (perhaps the war was over!) talk about the war, about Russia, about exhibitions … But the war was always with us.

Another essential meeting place, the “canteen” mentioned by Basler, had been started by a Russian artist, Marie Vassilieff—or Vassilyev, Vassilieva, Wassilieff—who, in 1958, was living in a retreat for painters and sculptors at Nogent-sur-Marne. She was then “old and short and solid,” her interviewer, Frederick S. Wight, wrote, “something of a dowager queen with a comfortable apartment of her own, and whatever comfort or support has come her way was no more than her due.” During World War I she worked as a nurse and conceived the idea of a restaurant cooperative in her studio. This was situated in an alley off the avenue du Maine at no. 21, now the Musée du Montparnasse. The studio was furnished “with odds and ends from the flea market, chairs and stools of different heights and sizes … and a sofa against one wall where Vassilieff slept. On the walls were paintings by Chagall and Modigliani, drawings by Picasso and Léger, and a wooden sculpture by Zadkine in the corner … In one corner, behind a curtain, was the kitchen where the cook Aurélie made food for forty-five people with only a two-burner gas range and one alcohol burner. For sixty-five centimes, one got soup, meat, vegetable, and salad or dessert … coffee or tea; wine was ten centimes extra.”

The unprepossessing building, left, in a cobbled alley, where Marie Vassilieff ran a café for artists during World War I (image credit 10.7)

Marevna, who went there regularly, said that Vassilieff was a “tiny, bandy-legged woman, practically a dwarf, with her round, white, browless face, her thin mouth and small teeth.” Everyone else went there as well. Painters, writers, and musicians came to discuss politics, often ending in a fight, to “argue over new art forms, to flirt and to dance to Zadkine’s mad music, ‘The Camel’s Tango.’ ” What began as an act of charity had evolved into an impromptu arts center which Vassilieff, with her penetrating, screechy voice, her commonsense insistence on good food at low prices, her tolerance for artistic exhibitionism, and her willingness to stay open late throughout the war, happily cultivated. Marevna continued, “Modi was a favoured guest at Vassilieva’s canteen, and of course she never charged him anything. Sometimes, when drunk, he would begin undressing under the eager eyes of the faded English and American girls who frequented the canteen. He would stand very erect and undo his girdle [sash] which must have been four or five feet long, then let his trousers slip down to his ankles … then display himself quite naked, slim and white, his torso arched.”

Being just as much of an exhibitionist as he was, Beà loved disguises and dressing up, or, rather, undressing. So one is inclined to believe, for once, that most unreliable witness to the “scandals” of Modigliani, André Salmon, the man who was even more the helpless pawn of a secret drug habit than his subject, and the writer who adhered to the French conceit that lives should be the starting point for one’s wildest fantasies. In his vie romancée, Modigliani, sa vie et son oeuvre of 1926, Salmon writes that the artist and the poet were about to go to a dinner, or perhaps a Quatz’ Arts ball, or perhaps a party at 21 avenue du Maine, and Beà had nothing to wear. This seems unlikely, but for the moment the reader suspends disbelief. Salmon then asserts that Modigliani, using phrases like, “Let me sort something out,” or “Leave this to me,” or “No prob,” decides to make a dress for her. He begins with one she owns, a dress made of the very finest tussore, a delicate neutral silk. She puts it on and he begins to improvise on his model, shortening the skirt and plunging the neckline. Then, using colored chalks, he appends butterflies, leaves, and garlands of flowers up and down the dress, the skirt, bodice, the breasts, waist, legs, buttocks, thighs, and ankles, melding silk to palpitating flesh in a fine artistic frenzy. The result causes a sensation. Beà, who is obliged to go barefoot as well as half naked because the designer has signed his name to an instep, shivers and smiles bravely. Perhaps it even happened.

Another account often repeated has Beatrice Hastings dressed up as Madame de Pompadour—or perhaps as Marie Antoinette in shepherdess outfit, carrying a crook. As she goes through the streets doing her morning shopping she carries a basket. It is full, not of flowers, fruit, or food but ducklings, quacking their heads off. Assuming one could get the ducklings in a time of food rationing and then somehow keep them all in a basket while one tripped through the streets in a crinoline, the staging seems hardly worth the momentary effect. What is interesting is that people thought her capable of such a stunt. In her way, Hastings was much of a risk taker as her lover, a factor that would even make scenes from the fertile imagination of a Salmon seem conceivable. This characteristic was a considerable factor in bringing their love affair to its sad and reckless finale.

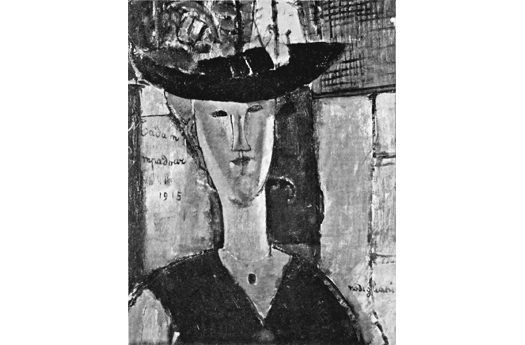

It is also clear that Hastings had worn such a costume for some occasion or other, because Madam Pompadour is the title of one of twelve paintings and many drawings that Modigliani executed of her in the years of their relationship. It was shown at the first art exhibition of the Lyre et Palette in 1916. The critic Louis Vauxcelles, for whom Cubism was anathema, wrote, “I look with interest at the new style of Modigliani.”

The Lyre et Palette was the invention of Émile Lejeune, a well-to-do young Swiss painter who was using a large studio at the end of a courtyard at 6 rue Huyghens in Montparnasse. For whatever reason, the government had closed the theatres and concert halls so Lejeune, responding to need much as Vassilieff had done, looked the situation over. There was plenty of room for a stage and an audience. He was able to rent a hundred chairs from a source in the Luxembourg Gardens, which they picked up and returned with the help of some capacious handcarts once a week. Blackouts, so omnipresent in Britain in World War II, were already being used in Paris. They taped over the single large skylight and used lantern lights to guide the audience through the darkness. Then Lejeune started his series of Saturday-evening concerts with a small group of musicians. That group would become the nucleus for “Les Six”—six composers and a poet—which became enormously successful after World War I: Francis Poulenc, Darius Milhaud, Germaine Tailleferre, Arthur Honegger, Georges Auric, Louis Durey, and Cocteau. Musical evenings led to poetry readings with Apollinaire, Cendrars, Jacob, Salmon, and the omnipresent Cocteau. Since there was plenty of wall space there were exhibitions as well and Guillaume set up his collection of primitive sculptures. Going to the Lyre et Palette became so fashionable that the limousines of the wealthy, slumming it from the Right Bank, would jam the narrow streets.

Madame Pompadour, Modigliani’s portrait of Beatrice Hastings, 1915 (image credit 10.8)

Moïse Kisling was responsible for introducing him to the Lyre et Palette crowd. He was working on an exhibition with Lejeune, and, when he learned that Modigliani did not have a single canvas available, approached Guillaume. That dealer had the standard arrangement by which Modigliani received a daily stipend, and whatever he produced went straight to his employer’s stockrooms. Kisling persuaded Guillaume to show Madame Pompadour and several other portraits. Being Kisling, he probably transported them himself on a handcart.

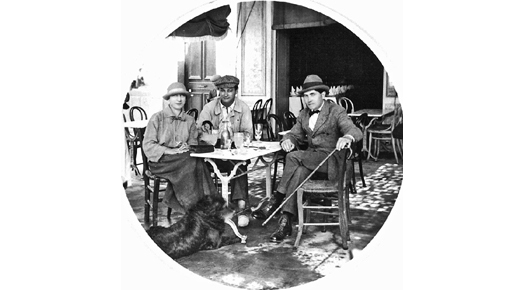

From left, Moïse Kisling and his wife Renée with Conrad Moricand, 1920 (image credit 10.9)

With his fringe of hair cut, as it seemed, with the aid of a pudding basin, the Polish-born Kisling looked like a choirboy, if one with an impish gleam in his eyes. Born in Cracow of well-to-do parents, Kisling received his art school training in that city and arrived in Montmartre in 1910 when he was just nineteen with a single louis d’or in his pocket. He had a natural gift of gravitating directly to the people who could help him. Within two years he had his first exhibition at the Salon d’Automne and gained a dealer the year after that. How did he do it? The secret, Kisling told Lejeune, was not to wear oneself out on a single painting but to paint several relatively quickly. He would then be able to offer a dealer a group of paintings at an attractive price, so that the dealer could make a tidy profit on each one. This was a relatively easy way of becoming known and building up some goodwill with dealers. Kisling was clever about getting critical attention as well. It was a simple matter of making lots of friends. The critics cost him “at least ten thousand francs a month, not in money but in lavish meals and free trips.” André Salmon, witness at his wedding and godfather to one of his sons, was a very special friend. Kisling could count on a nice review from Salmon whenever he had a show. But Modigliani had no money to spend wooing the critics, even if he had wanted to. So Salmon, as Czechowska said, did not waste his time looking at Modigliani’s paintings and rarely committed a word to print—at least during Modigliani’s lifetime.

One of a series of photographs taken by Jean Cocteau one summer day in 1916 when a group gathered for lunch. They included Modigliani and Picasso, flanked by a hatted André Salmon. (image credit 10.10)

At the outbreak of war Kisling joined the Foreign Legion. He was wounded, honorably discharged, and received French citizenship in recognition of his services. His family had helped support him and Kisling, who followed his own precepts to the letter, worked on four or five paintings at once and was soon well off. A young American friend of his, Victor Chapman-Chandler, an architecture student turned fighter pilot, died in an air battle in 1916, leaving Kisling a small fortune: five thousand francs. Claude de Voort, his biographer, noted that the artist had been born under a very lucky star. Kisling was soon ensconced in a comfortable apartment on the rue Joseph Bara, around the corner from the boulevard du Montparnasse. In years to come he would employ five servants and own two American cars.

There was something direct and uncomplicated about Kisling that communicated itself in his art. Work our age now finds shallow and sentimental accorded perfectly with popular tastes, although sophisticates like René Gimpel thought Kisling was a very bad painter. Kisling liked bright and glowing flowers, luscious bowls of fruit, pleasing still lifes, dramatic nudes with high breasts, shining eyes, and short black hair, and his portraits were freshly considered and generous. This marked his character. He was always ready for un petit verre, a dinner, a party, or a costume ball, and his door was always open. It was another rue du Delta with another benevolent patron. He became, someone said, “[t]he axis around which everything turned in Montparnasse life.” In old age he asked himself, “How was I able to come home more or less drunk every morning at seven and be up at nine when the model arrived? I washed myself and started to work … It was like that every day: mornings of work, afternoons constantly interrupted by innumerable visitors and evenings of running around that lasted at least until dawn.”

A bigger income only meant an excuse for bigger and better parties. Kisling’s Wednesday lunches, washed down with plenty of Armagnac, went on into the evening. One never knew whom one might find there: writers, actors, lawyers, politicians, scientists, musicians, architects, and, of course, artists. He once said, “I want life to be beautiful and for desirable women to have their desires and their lives to be colorful.” Given his eye for pretty women it is odd that Kisling married a strikingly plain girl. She was Renée Gros, the Catholic daughter of a French military officer, and he seems to have chosen her almost against his will. “Merde!” he told his friends at the Rotonde. “I’m marrying the daughter of an officer.” She was slim and strong, a forceful personality with a nose that dominated her narrow face. She also had an innate sense of style that took her into the category of “jolie laide.” Her hair was cut exactly like her husband’s—it was called the coupe garçonne at the time—she wore matching checked American cowboy shirts with overalls, she was an even more ferocious party giver than he was, and she could, it was said, blacken the eye of anyone who had the temerity to leave early. They were seen together everywhere. They were unforgettable.

Their wedding has been told and retold, with ever more embellishments; the best witness, as might be expected, turns out to be the bridegroom himself. The event, Kisling said, got off to a perfectly respectable start with a ceremony in the town hall of the cinquième. In honor of the occasion he wore his Sunday best, that is to say, he put a jacket over his overalls; Renée wore her usual charwoman’s outfit. André Salmon was the witness and Max Jacob was equally resplendent as a satanic Pierrot. About a dozen of them lunched at Leduc’s on the boulevard Raspail and then repaired to the Rotonde for some serious drinking.

Pretty soon the word got out that the Kislings had just got married and all the drinks were on the house. They arrived in great waves: the small and fat, tall and short, friends, strangers, clochards—the place was seething and all drinking, as they thought, on Kisling’s dime. Something had to be done fast. Kisling and friends rounded up about twenty fiacres, the oldest they could find, complete with decrepit horses, and made their escape just as the bill arrived. Their grandiose aim was to visit every whorehouse in Paris. It was doomed to fail, but they had fun trying in the rue Saint-Apolline, the rue de l’Échaudé, the rue Mazarine, and the Quartier Saint-Sulpice. The procedure was always the same: peremptory knocks on the door, startled owners, calls for champagne all round, friendly chats with ladies of the night, and abrupt departures nicely timed to avoid the inevitable moment of reckoning.

Finally the motley band arrived at 3 rue Joseph Bara eight flights up (seventh floor in France). The happy hordes, believing a vast banquet awaited them, made the climb and packed the rooms to the rafters. Kisling mentioned in passing that there were a few friendly scuffles and some knives came out before being sheathed in the general spirit of goodwill. Kind friends went looking for reinforcements: red wine, Calvados, Benedictine, or anything. Pretty soon no one noticed that there was not going to be any food. In fact, all went well until Kisling came upon a young man in a corner who had found a cardboard box full of all his drawings and was industriously tearing them up into tiny pieces and looking fondly at the growing piles of paper. With the help of a huge Norwegian, the offender was hurled unceremoniously down the stairs. Kisling found out later he had been taken to the hospital but unfortunately survived. What with the smoking and the alcoholic haze, Kisling began to forget things after awhile and apparently did not remember that, at some point, Jacob stood up and started on his famous impersonations that made everybody laugh. Modigliani kept interrupting. Couldn’t he play Dante? He knew just how to do it. Please, couldn’t he play Dante? The crowd told him to shut up.

Once the name of Shakespeare was mentioned Modigliani was not to be stopped. He must play Hamlet’s ghost. “He rushed to the small room adjoining the studio, the ‘bridal suite.’ He came out again swathed in classic sartorial fashion in a white sheet. At the door he started playing the part of the ghost of Hamlet’s father: ‘God or man, which art thou?’—with such panache that Max Jacob, at times an outstanding actor, at once ceased his impressions,” Salmon recalled.

Now Modigliani was free to shout, now he alone dominated the stage … Straight away our Amedeo instinctively found the right words. At first they seemed meaningless, but by pronouncing or screaming them in his own unique way he made them serve his purpose, namely to communicate to the spectators that a dead being can continue to plague the living from beyond the grave … And so suddenly he began yelling—I don’t think you hear this call nowadays but at the time you heard it every day in the streets in Paris—“Barrels, barrels, have you any barrels?”

The accursed ghost, condemned for all eternity to roll before him his cask full of hideous memories, full of sin, full of pangs of conscience and tears! The brand-new Madame Kisling, née Renée-Jean, broke this awe-inspiring spell with the pained scream of a young bride and dutiful housewife: “My bridal linen!”

Her husband, quite nude, was scooped out of the gutter on the boulevard du Montparnasse four days later, and the party was finally over.

As the Siege of Paris wore on in November 1914 Modigliani and his new love settled into a routine of comfortable domesticity. On All Saints Day, the cemetery of Montparnasse being just around the corner, they went to pay their respects to the fallen. Their housekeeper had been to the market at five a.m. to buy a wreath, and the boulevard du Montparnasse was packed with flower stalls and so many crowds that one was, Hastings wrote, almost carried along. Once in the cemetery one found small groups huddled around new graves, sobbing. And there was something worse: a woman lying flat on a grave. It seemed her husband had been killed in August and she was going to lie there until she died with him. Every evening, she had to be forcibly ejected. It was all too sad; Hastings left as soon as she could.

Now they were back indoors, drinking tea, watching the flames flicker in the stove and listening to the rain on the roof; it was just like being in London. They read the papers to each other, singling out the sections about corpses, both German and French, rotting in the trenches, and agreed once more about the folly of the war. At least the British working classes had stopped joining up with anything like zeal, having begun to learn the truth about the capitalists’ war. What was needed were a few Zeppelins over London to bring the plutocrats to their senses. The same issue contained a satirical verse that she wrote under one of her noms de plume, Cyril S. Davis. It was called “The British Profiteer,” and sung to the tune of “The British Grenadier”:

Some talk of Shaw and Masefield, and some of Begbie, too,

But what of dear old Rothschild? was Briton e’er more true?

For all the world’s great martyrs, there’s none whom we revere,

With a cent. per cent., per cent., per cent.,

Like a British Profiteer.

Warmed by such thoughts they went for a walk to the Porte d’Orléans on the edge of the city, “where the trees and the barbed wire and the sharp iron points still lie about that were to arrest the onslaught of the German cavalry.” Then they indulged in their favorite pastime, hunting for books up and down the bouquinistes along the Seine. There were wonderful cheap editions one could buy for a half penny, or five centimes, of the French memoirists, “Mesdames” de Staël, de la Fayette, des Ursins, Roland, Depinay, de Caylus, de Maintenon, and de Genlis. They would immerse themselves in the past for the duration.

Modigliani had begun to work on preparatory sketches that would result in portrait after portrait of his amour, the most he would execute of any woman except one. Alice Morning, having written her latest column, went for a walk in the rain, got soaked, and was now “half delirious” with influenza. Fortunately, “somebody” had made a very pretty drawing of her. “I look like the best type of Virgin Mary, without any worldly accessories, as it were. But what do I care about it now—my career is nothing but a sneeze.” One assumes dozens were finished before Modigliani felt confident enough to commit his ideas to paint. He painted himself as Pierrot during his relationship with Hastings. Complete with black cap and ruffle, one eye socket, the left, was blank, and the other eye looked outward. A year later, 1916, either he or Beà had the notion of painting a companion portrait of her. The portrait is never described as such, but it is so much of a mirror image that the possibility is intriguing. Pierrot’s pose, in three-quarter face, is turned to the left of the viewer; in the 1916 portrait of Beà, the pose is to the right. Her features are more delicately drawn but otherwise identical; here are the same highly marked eyebrows, the same upturned nose, the same position of the mouth, the same jawline, and the same neck, turned at the same angle. There are some minor differences; the treatment of the eyes is more conventional and the lips are parted. The color schemes are complementary, and the general effect suggests that the two were meant to be hung together, so that each is looking in the direction of the other, in the middle of a conversation.

As for Madam Pompadour, this extraordinary achievement has been admired and analyzed ever since its debut at the Lyre et Palette. Hastings is seen full face and wearing a hat that looks more like a boat. The eyes are steady and direct, the nose flattened, and the lips pursed, almost as if at the end of an argument she has conclusively won. Many of Modigliani’s portraits of her lack any sense of her personality but this one, Werner Schmalenbach comments, is one of his most delightful works, “one example (among many) of the extraordinary formal grace that is so enchanting a feature of the portraits of 1915 and 1916.” Modigliani’s career as a sculptor had come and gone but a seminal change had taken place. He was launched on “the series of major portraits that show the artist immediately at the peak of his genius.”

Pierrot, often described as a self-portrait, was painted by Modigliani in 1915. (image credit 10.11)

What was to be done, however, about Maldoror? His shadow stood between them, and quite soon, because Alice Morning devotes considerable space to his spectral presence in the autumn of 1914. This precocious poet Isidore Ducasse, the so-called Comte de Lautréamont, was, as she must have known, her lover’s ghost, and his obsession. What a “poor, self-tormented creature” Maldoror was, after all. Had he lived, “no earthly refuge for him was possible but an asylum.” Modigliani was just now drawing his portrait, “with the head of an ostrich and a eunuch’s flank and trying to hide in the sand!” And how puerile Maldoror’s thoughts were. “One would not wonder that the ‘O silken-eyed poulp!’ and similar sentences of the seventeen-year-old … seemed mysteriously ironic to people who will never get past this nebular age.” She was using the only kind of exorcism she knew: “Imagine ‘Maldoror’ in Paris today bleating at seventeen about the war—‘This stupid, uninteresting comedy. I salute you, ancient sea!’ and so on.” Was her lover laughing? Oh well, there was no accounting for an adolescent Frenchman; they were always peculiarly unbalanced. The point to make was that Maldoror had outlived whatever purpose he once served. It was time to bury him.