“Life Is a Gift”

Quelle est cette île triste et noire?—C’est Cythère

—CHARLES BAUDELAIRE, “Un Voyage à Cythère”

THE PERSON who did welcome the arrival of baby Jeanne was her father. Lunia Czechowska recalled, “Modigliani was absolutely thrilled. He adored this baby and nothing else in the world existed for him except her. He never stopped talking about her beauty and charm. He did not exaggerate; I’ve never seen such a pretty baby, blonde, plump, ravishing eyes a nutty brown, long curly eyelashes and a delicious little mouth.” Writing back to his mother, to whom he had sent the news of Jeanne’s birth, he said, “The baby is well and so am I. You have always been so much of a mother that I am not surprised at your feeling like a grandmother, even outside the bonds of matrimony.” It was not so long ago that unwanted babies, especially illegitimate ones, were bundled off to wet nurses in obscure villages who could be depended upon to starve them until they died. Modigliani must have been well aware of this common practice because he went to very great trouble, according to Czechowska, to find a genuinely loving substitute for Jeanne’s mother.

This was necessary because when she was three weeks old her mother claimed she could do nothing with her and neither, she said, could her mother. She was inexperienced, the birth had been tiring, and someone subjected to such a drumbeat of disapproval could be forgiven if she was not particularly delighted by the new arrival. She was “not much of a mother,” Jeanne told Aniouta. With a half smile she rated herself as a zero, indicating the score with her fingers. On the other hand, “As a husband Modigliani was very good,” her mother said. André began referring to his sister as their “lost ewe” and wrote a note in his diary about how his dear little mother had kept all of her sorrow and resentment bottled up for so long. How sad it all was.

Modigliani, by contrast, was full of new energy. At the end of May, leaving Jeanne still in Nice, he returned to Paris. According to Lunia Czechowska, he was looking better, had stopped drinking, and was being careful about his health, because he had a daughter to live for. He was living a normal life. She wrote, “I have kept a lovely souvenir of our long conversations while I was posing for my portraits.” (He painted her repeatedly.) “He talked about anything and everything, his mother, Livorno and above all his darling baby. He had this simple and touching dream, to go back to Italy, live near his mother and get his health back. He would not be completely happy until he had a proper apartment with a real dining room, and his daughter beside him, in short, living like anyone else. His exuberant imagination spun endless dreams.”

Meanwhile he was working at top speed. Modigliani painted as many portraits of Hanka, Zborowski’s companion, servants, adolescent boys, mothers with babies, and, in particular, small girls. There is an unusually large, almost lifesize painting of an eight- or nine-year-old that perfectly expresses his enchanting ability to paint adorable subjects without ever descending into sentimentality. She just stands there, looking at the viewer, her hands clasped, wearing a long blue dress, a ribbon in her hair, and an appealing expression. Could he have been thinking of the little girl Jeanne would one day become? Canvas after canvas was finished with lightning speed because, that summer, something stupendous was about to happen. He was going to show nine paintings and fifty drawings in London.

Paris in 1919 was “sad and beautiful,” Margaret MacMillan wrote in Paris 1919. “Signs of the war that had just ended were everywhere: the refugees from the devastated regions in the north; the captured German cannon in the Place de la Concorde and the Champs-Elysées; the piles of rubble and boarded-up windows where German bombs had fallen … The great windows in the cathedral of Notre-Dame were missing their stained glass, which had been stored for safety; in their place, pale yellow panes washed the interior with a tepid light. There were severe shortages of coal, milk and bread.”

On the other hand the weather was perfection. Encouraged by a heavy rainfall the grass was lush and spring flowering bulbs were at their peak. “Along the quais the crowds gathered to watch the rising waters, while buskers sang of France’s great victory over Germany and of the new world that was coming.” After a year in the south of France Jeanne was at last ready to return. A close dating reveals that Modigliani returned to Paris on May 31. Three weeks later, on June 24, Jeanne sent him a telegram, care of Zborowski, asking for her train fare home. That apparently came quickly because she returned a week later, accompanied by her mother. Curiously, André’s diary does not record that the family was back together again until July 13. It was a Sunday, at seven in the morning. “The father seemed thrilled to recover his family,” Restellini wrote. “André described an apartment in total chaos.” There was no mention of a baby in the family gathering and none either of what Jeanne must have known by then, that she was expecting another child. However, the discovery must have precipitated a curious note that Modigliani signed on July 7, promising to marry “Mlle Jane Hebuterne” (sic), “as soon as the documents arrive.” (This was, presumably, a reference to legal papers from Italy.) Marevna, who saw him shortly after he returned, thought he had gained weight. He seemed in good spirits and was joking about becoming a father for the second time. “It’s unbelievable. It’s sickening!”

During the month before Jeanne and the baby returned, Modigliani would take Lunia for long walks in the Luxembourg Gardens—it was very hot that summer. Sometimes they went to the cinema and ended up dining at Rosalie’s. He was always talking about returning to Italy and the little girl he would never see grow up. He was also talking about London. The great international world of art and artists was coming back to life. In particular, the most important exhibition of French art in London in almost a decade was taking place that summer. The location was, curiously enough, in a department store, Heal’s, that had opened an art gallery two years before. Since the gallery was just underneath its mansard roof it was named the Mansard Gallery. Some thirty-nine artists—Dufy, Kisling, Léger, Matisse, Picasso, and many others—were represented. Modigliani, with fifty-nine works, had the most in the show. He was becoming as well known in London as in Paris; examples of his sculpture, shown at the Whitechapel Gallery five years before, had been singled out for special mention in avant-garde circles. It is also clear that British critics saw his worth long before the Paris critics did. (One wonders: was it because, being less corrupt, they did not have to be paid?) The first real discussion of Modigliani’s art was not published in Paris but in London by the discerning artist and critic Roger Fry. Furthermore the catalog for the Mansard Gallery was written by the well-known writer Arnold Bennett, who remarked, “I am determined to say that the four figure subjects of Modigliani seem to me to have a suspicious resemblance to masterpieces.” Other glowing comments followed. The Observer wrote, “Modigliani stands in front … and shows a strong alliance with the early Florentine painters.” The Burlington Magazine recorded, “Modigliani’s uncommon feeling for character finds expression through an extreme simplification of colour and contour and the most astonishing distortions.”

The English artist-critic Roger Fry, c. 1925 (image credit 13.1)

The critics in London were not alone in appreciating Modigliani. Osbert Sitwell wrote that he and his brother, Sacheverell, had organized the Mansard Gallery show in collaboration with Zborowski. Sitwell wrote, “With flat, Slavonic features, brown almond-shaped eyes, and a beard which might have been shaped out of beaver’s fur, ostensibly he was a kind, soft businessman, and a poet as well. He had an air of melancholy, to which the fact that he spoke no English, and could not find his way about London … added.” Sitwell continued, “Rather than the great established names, and famous masters, it was the newcomers, such artists as Modigliani and Utrillo, who made the sensation in this show.” As a reward for their services Zborowski offered them a single picture from the show at a wholesale price. The Sitwells chose Modigliani’s “superb” Peasant Girl, which they bought for the very great bargain of four pounds. The average gallery price for one of his paintings at the time was between thirty and a hundred pounds.

It was Modigliani’s moment of triumph. Suddenly everybody who was anybody wanted a Modigliani. Bennett bought a nude and a portrait of Czechowska. Years later all kinds of collectors would claim to have been the first to appreciate his work. One of them was Hugh Blaker, a painter, writer, art critic, and collector who records in his diary that Zborowski appeared in London in 1919 (apparently before the show) carrying several oils stripped of their stretchers and frames to avoid freight charges. He unrolled them on the floor and Blaker immediately bought four; one, Le Petit Paysan, is now in the Tate Gallery collection. “So far as I know I was the only man in London to care a tuppeny damn about ’em.” Another pair of eyes spotted Le Petit Paysan and appreciated it before Blaker did. He was the young Kenneth Clark, future British art historian, author, television personality, and museum official. Clark, then aged sixteen, had been given the handsome present of one hundred pounds and told to buy a picture. This painting of a young peasant boy caught his interest. “It seemed ridiculous to buy the first picture I saw, but after a long search I could find nothing I liked so well, so I timidly asked the price. It was sixty pounds and the painter’s name was Modigliani.” But when he got back to his parents’ elegant flat in Berkeley Square he realized that the choice was never going to fit among all their gilt-framed Barbizon paintings. As he recorded, Blaker bought it instead and eventually sold it to the Tate. In the end everyone was better off, except, of course, the young collector.

That August of 1919 Modigliani should have been in London but had contracted another bout of influenza and was too ill to travel. The Sitwells were then given a firsthand demonstration of the cutthroat world of the Paris art market. “I recall how, during the period of the exhibition, when Modigliani, recovering from a serious crisis of his disease, suffered a grave relapse, a telegramme came for Zborowski,” Osbert Sitwell wrote. Zborowski then came to the Sitwells with a message that all sales should be put on hold. In this case, he was doing the bidding of Paul Guillaume, who owned most of the works in the show and knew the prices would double and triple if and when Modigliani died. It seemed callous in the extreme, but as Guillaume’s biographer, Colette Giraudon, pointed out, it was a kind of compliment; the market had now decided that whether Modigliani lived or died was a matter of some importance. In any event, as Sitwell drily concluded, “Modigliani did not immediately comply with the program drawn up for him.”

Time and again Modigliani had cheated death, but this time the odds were hopelessly stacked against him. Few people know that tuberculosis, a bacillus that primarily attacks the lungs, can migrate anywhere in the body and can infect the spine, lymph nodes, genitourinary tract, gastrointestinal, or peritoneum, and so on. In Modigliani’s case the bacillus went to the brain. Tubercular (or tuberculous) meningitis, the cause of death cited on his death certificate, is an infection of the meninges, the membrane covering the brain and spinal cord, and was, in the early twentieth century, the most widespread form of meningitis. Nowadays it can be rapidly cured with antibiotics, but if left untreated it leads to blindness and death. In adults it is an outgrowth of pulmonary tuberculosis, exacerbated by malnutrition, excessive alcohol and drug use, or other disorders that compromise the immune system. The British Medical Research Council has identified three stages in the development of the disease, going from headaches, general apathy, irritability, fever, and loss of appetite to delirium and coma.

So it is easy to see how Modigliani could have attributed his declining health, that autumn and winter of 1919, to a slower-than-usual recovery from the attack that laid him low in August. Before X-rays came into common use Paul Alexandre would have known the only way to suspect tubercular meningitis was atypical behavior. He would have been aware that this terrible infection, attacking the brain itself, killing cells, caused swelling, pressure, massive lesions, and all kinds of bizarre changes in personality. But Dr. Alexandre, returning from the hell of war, had his own family problems to deal with, Modigliani’s trail of addresses would have confounded anybody, and getting in touch was not a pressing issue for him at that particular moment.

Modigliani had a devoted companion, but a young and inexperienced one. If anyone had urged him to see a doctor his response would have been predictable. Whatever Modigliani knew or sensed about his illness would have been drowned in a bottle of rum—anything rather than face the terrible ministrations of the medical profession. Yet he somehow knew. Among his final words was a kind of apology: “You know, I only have a little bit of brain left.” One suspects that most of the out-of-control behavior described, but not dated or documented in such biographies as Artist Quarter, is actually attributable to the last months of his life.

Some thirty-five years later, in 1956, Moïse Kisling, now in retirement at Sanary-sur-Mer in the Midi, struck up a friendship with his doctor, also a psychologist, who became a close friend. Eventually he spent many hours with the doctor, Tony Kunstlich, describing Modigliani’s symptoms and behavior and asking for a diagnosis.

“To judge from the meagre evidence available, I am led to believe that it was an attack of cerebral meningitis of a tubercular nature,” Dr. Kunstlich wrote.

We know that the deplorable conditions in which the painter lived in Paris, and the combination of his unwholesome lodgings, his irregular meals, his turbulent sexual life, and his addiction to alcohol and drugs, quickly destroyed the delicate balance of health which had been maintained so long as he remained with his family.

We know that tubercular meningitis in adults is very different from the kind which spreads rapidly throughout the bodies of younger victims. Once it takes hold in an adult, it develops gradually over a period of months or even years without giving rise to any outstanding symptoms. Sometimes the only signs of tubercular encephalic disorder are headaches, visual and auditory disturbances, and, in particular, modification in the patient’s character, as evidenced by extreme irritability, violent outbursts of anger, unsociability, withdrawal into the self, and so on.

It is only in the final phase that the classic symptoms of meningitis supervene in the form of paralysis, rigidity, comatose states.

In the first flush of the success of his London show Modigliani did something uncharacteristic: he asked for a present. Would Zbo bring him back a pair of shoes from London? Zborowski would. He also included a magnificent English wool scarf. The flurry of attention and the sales were heartening but the praise meant most. Indenbaum recalled that sometime after the show, meeting Modigliani at the Rotonde, the latter brought out a Jewish newspaper published in Britain for him to read. “It was an article full of praise for Modi. ‘C’est magnifique,’ he said … and was so moved that he kissed the paper before putting it back in his pocket. It just shows how terribly he needed, and looked for some praise, some comprehension.” Modigliani was working as hard as ever, this time for the exhibition of the Salon d’Automne at the Grand Palais that was opening for a month’s stay on November 1, 1919, where he showed four paintings. But his energy was flagging—no doubt the early stages of tubercular meningitis were making themselves felt—he had started drinking again to quiet his nerves, and alcohol is known to help reduce pressure on the brain. That he was suffering from headaches is likely. He had always been restless and this nervous trait seemed to have increased. Lipchitz had repeatedly tried to draw him but Modigliani “fidgeted, smoked,” and moved around so much—in short, he never succeeded. Vlaminck, one of Modigliani’s admirers and a close observer, noticed that during the last year of his life the artist was “continually in a state of febrile agitation. The least vexation would make him wildly excited.”

Vlaminck recalled that Modigliani was sketching at the Rotonde one day when an American woman visitor agreed to have her portrait made. The sketch completed, Modigliani graciously offered it to her, without signing it. She liked it very much. She wanted a signature.

“Infuriated by her greed, which he sensed immediately, he took the drawing and scrawled a signature across the whole sheet in enormous letters.” Marie Vassilieff happened to meet him on the street not long before he died and said, “I couldn’t believe the change in him. He had lost his teeth; his hair was flat, straight; he had lost all beauty. ‘I’m for it, Marie,’ he said.”

Still, he worked on. After painting everyone in sight in the Zborowski household Modigliani turned his attention to one of its new arrivals. She was Paulette Jourdain, just fourteen, working as a live-in maid in that chaotic world of works in progress, constant arrivals and departures, bargaining, and the ever-present smell of turpentine. She was slim and pretty, scared but shrewd. She stayed on as a model, became Zborowski’s lover, and in due course gave birth. Hanka, who was childless, and the art dealer, ever resourceful, adopted the baby and raised it as their own. Eventually Paulette Jourdain became an art dealer herself and was constantly being interviewed in the years to come for her reminiscences about Montparnasse.

The interviewer Enzo Maiolino, who visited her in 1969, was amazed to find her apartment full of Modigliani memorabilia: books, photographs, one of his palettes, and a rare copy of his death mask. She was like that, quiet and careful, not missing much.

Paulette Jourdain seems to have realized, young as she was, when she agreed to sit for her portrait, that she was in the presence of a remarkable man. She was nervous but by now Modigliani was a master at putting people at their ease. She was to sit however she liked as long as she was quite comfortable, so she sat easily, her hands in her lap. He talked freely and fluently while he worked and whatever she said seemed to make him laugh. He would say that someday they would all go to Rome. She would want to know where they were going to find the money. He would concede she had a point, and look thoughtful. He never got angry and was polite and attentive; she concluded that he was a refined, likable man.

Sometimes he talked to himself in Italian, or recited Dante, or sang the toast from La Traviata, “Libiamo, libiam nei lieti calici…” His voice, she recalled, “was rather light, almost feminine and yet more modulated,” so distinctive that if she heard it anywhere she would immediately know who it was. His brother, Giuseppe Emanuele, so much Modigliani’s opposite in build and appearance, had the same voice. Sometimes she went on an errand. There was a “bougnat,” or charcoal seller, across the street on the rue de la Grande Chaumière. She would be sent there with an empty flat-shaped bottle, the bougnat would fill it with measures of rum, and when she got back to the top of the stairs Modigliani would be waiting with a glass in his hand.

“But in the studio Modigliani was never drunk, and he was never drunk in Zborowski’s house. But he didn’t know that I happened to see him drunk all the same. Then I would hide or change streets. And the next day, referring to his ‘weaving around’ from one side of the street, I had the impudence to say to him:

“ ‘Yesterday it seems the street was not wide enough.’ He knew what I was talking about but was not offended.”

The young Paulette Jourdain, who joined Zborowski’s household when she was fourteen and ended up inheriting his art gallery business (image credit 13.2)

Zborowski also sent her on errands, either to Modigliani’s studio or the Rotonde whenever he had some money for Modigliani. If to the Rotonde, as soon as other painters in his stable saw her coming they would pounce. “Is the money for me?…Is it for me?,” and she would point to Modigliani and reply, “It’s for the little one.” The proprietor of the café, M. Libion, would chalk up each artist’s running account on a slate and as the money changed hands the call would go up, “Modigliani, are you going to settle your slate?,” a pertinent question the answer to which is not recorded.

If she was taking the money to Modigliani’s studio she often found him in bed. Sometimes he would break a date for a session, saying that he felt too tired. He never once said he was ill. She believed him; it was December 1919, a month before he died.

The young Swedish girl Thora Klincköwstrom, whom Modigliani painted, 1919 (image credit 13.3)

Thora Klincköwstrom, a young Swedish girl who arrived in Paris that autumn to study sculpture, was another of Modigliani’s last models. She was introduced to the painter by her future husband, Nils Dardel, at the Rotonde. Nils told her, “He is a genius. When I was here four years ago he was one of my friends and you couldn’t find a more beautiful young man than he. Now he is no longer young and in addition completely drunk.” Before long Modigliani joined them at their table. Thora described him as “rather small, weather-beaten, with black tousled hair and the most beautiful hot, dark eyes. He came in his black velvet suit with his red silk scarf carelessly knotted around his neck.” He was talking loudly and laughing a lot. For once he had not come prepared, so the waiter found him some pieces of squared paper and he drew her portrait there and then. On one of the sketches he added his favorite maxim:

La vita è un dono,

dei pochi ai molti,

di coloro che sanno e che hanno

a coloro che non sanno e che non hanno.

(Life is a gift, from the few to the many,

from those who know and have

to those who do not know and do not have.)

He graciously offered her the drawings, but she hesitated to take them. Her lack of French or Italian was a major barrier, but she was a bit afraid of him as well and thought he had made her look ugly. Still, when he wrote his address on the inside cover of a box of Gitanes cigarettes and invited her to pose for him, she agreed.

Modigliani’s portrait of Thora, 1919 (image credit 13.4)

With her friend Annie Bjarne acting as chaperone they climbed the steep staircase to his top-floor flat at 8 rue de la Grande Chaumière and found two large, bare rooms and huge windows. “It was very cold that winter and the fumes from the one stove had completely blackened the wall behind it. No curtains, just one large table with his painting materials on it along with a glass and a bottle of rum, two chairs and an easel.” She was shocked to find the floor littered with coal, charcoal, and matches. But when she offered to give it a quick sweeping he seemed quite offended and said he liked it that way.

While Annie Bjarne sat in a corner Modigliani was constantly on the move, looking at his work from a distance, eyes half closed, or inspecting its surface minutely. He would back up, stare at Thora, then begin whistling and hissing, singing snatches of songs in Italian and, every once in awhile, look at her young friend ruminatively and in fact he ended up painting her as well. From time to time he stopped to drink the rum, “and he really did cough a lot.” While she was posing Jeanne Hébuterne made a discreet appearance. She seemed self-effacing “and I could not discern what fire and passion might be concealed behind her air of very great reserve.” Her girlish plaits made her seem very young; she looked tired and not particularly happy to find visitors. Modigliani explained that Jeanne was expecting their second child and that their baby was staying with a nurse in the countryside outside Orléans. Then Thora noticed that there was a photograph of him pinned to the wall near the easel, that had been taken a few years before. She asked if she could have it. He said that unfortunately it was the only one left and the negative had been destroyed. “If you won’t give it to me I’ll just help myself,” she insisted. So he did.

Not surprisingly she did not like the painting any more than she had the drawings but was too polite to tell him. So she did not buy it and lost track of its whereabouts until it went on sale in Stockholm in the 1970s. But she never forgot Modigliani.

Modigliani was also working on his final series of nudes at his studio in the Zborowski apartment on the rue Joseph Bara. He worked there for practical reasons having to do with keeping his models comfortable—an impossibility at the rue de la Grande Chaumière, where it was always either too hot or too cold. So his last great series of nudes was painted in the relative comfort of the Zborowski dining room. Since the days when he had painted Jean Alexandre’s Amazon, he had been alert to the sensibilities of his female sitters, especially those in need of a change of costume, or nude, who would expect to dress and undress with a minimum of privacy. Anyone else intruding on the scene was not wanted, and Zborowski could not resist popping in and out to see how things were going. At any point Modigliani would have found the interruption irritating; at this stage in the progress of his disease it was intolerable.

As Lunia Czechowska records, one day his dealer arrived unannounced for the umpteenth time just as Modigliani was finishing another nude portrait. She was “a ravishing blond [the painting, a rose nude, was bought by Carco] and Zborowski, who could not contain himself, opened the door.” Modigliani exploded. Zborowski went for a walk with Hanka in a hurry. “But a moment later I heard the patter of bare feet and discovered the poor girl, in a panic, running through the house clutching her clothes looking for somewhere to get dressed. I went into the dining room and found Modigliani attacking his canvas with furious slashes of the brush. I had a lot of trouble convincing him that Zbo came in by accident and to please not destroy this work of art.”

Modigliani characteristically washed himself from head to foot, using a basin, whenever he finished a painting. That same afternoon, the painting repaired, he disappeared. Suddenly Czechowska heard the sound of falling water and then, breaking china. Modigliani had balanced his washbasin on the edge of an open window. It fell into the street below, and the concierge was beside herself. As for Modigliani, he sat himself down precariously on the edge of the window and began singing at the top of his voice. Czechowska had visions of seeing him crashing into the street as well. It was then early evening. She lit a candle and invited him to stay for dinner, an invitation that was sure to be accepted, and he gradually calmed down. While she was in the kitchen preparing the meal he asked her to look up for a moment. By the light of a candle he drew an admirable portrait, embellishing it with his favorite aphorism of these final months, “Life is a gift …”

Czechowska wrote, “I remember another story about Modigliani’s adventures with water. Kisling had a bathtub [a luxury in those days] which he invited Modigliani to use whenever he liked.” One day, taking advantage of their absence, Modigliani went upstairs for his usual bath; Czechowska could hear him singing. What she did not hear was water overflowing; Renée Kisling returned to find her apartment completely flooded. Modigliani had forgotten to turn off the taps. The next thing she knew, a nude Modigliani was out on the landing clutching his clothes and Renée Kisling was hurling curses and threatening eternal damnation. They all had a good laugh about it later. “Renée did not hold a grudge, Modigliani went on using their bathtub and the whole story ended up being the subject of some good-natured teasing.”

Once Jeanne and Dedo were back in Paris, and until they found a satisfactory replacement for their nurse, baby Jeanne stayed with Lunia. It seems odd that the notion that Jeanne might care for her own infant was dismissed by everyone, herself included. Lunia did not know how to handle a baby either but was willing to try. So this was one more reason for Modigliani to haunt the rue Joseph Bara, although Lunia was at pains not to let him in at night. One evening they heard a familiar voice singing at top volume as he came up the rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs and knew there was trouble ahead. It was late. He was with Utrillo and they both wanted to come in but the concierge would not let them and told them to go home. Lunia heard the whole exchange, but did not dare to intervene because she knew the Zborowskis would be angry. So she, like they, pretended to be asleep. The next thing she knew, Modigliani and Utrillo were sitting on the sidewalk opposite and Modigliani was calling her name, begging for news of the baby. Again, she did not respond. He was there for several hours and she listened, in anguish to think how unhappy he must be. Finally the two of them left. “If I had been alone I would certainly have let him come in.” That happened occasionally. He would come up the stairs and sit down beside his child, looking at her so fixedly that he would end up by falling asleep beside her. “Poor dear friend,” she wrote, “these were the only moments when he had his little girl to himself.”

Sometime that autumn Czechowska decided to leave Paris for the south. It was necessary for her health, she wrote, although she did not explain why. There are plenty of hints in her narrative that she and Dedo were more than just friendly, although she resists calling it a love affair. She simply states that he wanted to accompany her and Zbo and Hanka were all for it. But Jeanne, by now heavily pregnant, did not want to travel and did not want to be left alone in Paris either. The impression left is that this was a wasted opportunity. Had Modigliani been able to go with her, he might have survived. (This, of course, was unlikely.) But her hands were tied because he had a wife to look after him. So what happened subsequently was Jeanne’s fault. This is not stated but it is very much implied. Lunia left alone. She and Modigliani promised each other they would meet again soon. But, “hélas,” she wrote, they never did.

Reliable witnesses record that Jeanne went to visit her baby once a week, but what else she did with her time can only be conjectured. It is clear that she remained in the apartment when Modigliani went out at night. She discreetly disappeared whenever he was painting there. She must have been drawing and painting, perhaps making clothes, or out buying food and painting supplies. The stairs to the floors of this annex at the end of the courtyard, which contains artists’ quarters, are much longer than the usual flights, owing to high-ceilinged studios, and full of twists and turns. They are of bare pine and somehow forbidding, devoid of paint and looking much as they must have done eighty years ago. Now, as then, there is no elevator between floors. As one climbs one notices the scuffed wood, worn thin, the narrowness of the tread, the peeling walls and high, small windows that seem to cast a perpetual gloom. A very pregnant Jeanne would not have particularly wanted to go out at night, and carrying heavy loads up those stairs would have been an increasing burden. Somewhere under the eaves was a princess, safe, hidden, and marooned in her tower.

In Montparnasse vivant the author, Gabriel Fournier, writes that Jeanne attempted to reconcile with her parents but that the reconciliation was brief. It must have been an enormous disappointment. A self-dramatizer like Modigliani will command the attention and the quiet girl in his shadow is ignored. Yet her dilemma was, if anything, as desperate as his. If and when he died, he left her a young woman with two children. Judging by her attitude toward her first pregnancy, the second child was unlikely to have been any more wanted. She and her children had already run the considerable risk of contracting tuberculosis themselves. She would naturally want to marry. In the early spring of 1919, Modigliani wrote to tell Zborowski that his brother Emanuele was arranging for the needed legal papers and that the business was almost finished. Yet, six months later, they were still not married.

Jeanne had no status except as a common-law wife, that is to say, none. The possibility that she would be destitute was real unless her parents took her back. Would they? Did they even know Modigliani was ill with tuberculosis? (Luc Prunet doubts they ever did.) How much would they have intervened? More to the point, how wounded had she become? Would she ever go back?

There is a further question of how comfortable the two were with each other in the day-to-day intimacy of a close relationship. Marc Restellini, who has made a study of the final six months of Modigliani’s life, believes that, by 1919, a sense of disillusion with Jeanne can be deduced from the increasingly unflattering portraits he paints of her. A postcard he sent her while they were living separately in Nice provides a clue: “Bonjour Monstre.” The teasing tone reveals some sense of exasperation. There was something unsettling in her eerie silences, her reserve, her determination never to reveal a chink in her emotional armor. To someone with exacerbated nerves and a steadily declining health, perhaps nursing a hangover and feverish, such stoicism would seem unbearable. He wanted a Lunia at home, someone to soothe him, distract him, gloss over his tormented feelings, excuse his erratic behavior, and coax him into a good mood. In short, a maternal solicitude. But the evidence suggests that Jeanne was too much his follower, and he too dominant, to allow this to happen. She could only follow with a kind of terrible patience.

His original response to her as a sitter had been rapturous. An early drawing, which incidentally dates their meeting to the end of 1916, if not before, has her in hat and coat, two long pigtails framing her face. Portraits, the first of many, came soon after. Although Modigliani’s stylistic simplifications are still evident (the emphasis on the nose, the endlessly attenuated neck), the early portraits and drawings give a vivid sense of the sitter. In one she is shown three-quarter face, as if in the act of turning toward the artist, her look alert and questioning. In another she is seen full face, looking directly up at the viewer with a grave, penetrating stare; in yet another, a study of her profile reveals the same look of serious-minded concentration. Jeanne Modigliani observed that “the composition becomes more flowing and takes on a calligraphic elegance; the canvas is visible between the thin brushstrokes and the color recalls the luminous freshness of a Persian miniature.” In Modigliani’s portraits of Jeanne we see her with shoulders bared only once, and only two drawings exist of her in the nude; she is dancing in the first and serves as a model for the Berthe Weill exhibition poster in the other. Since it is almost axiomatic that nude models slept with their artists, before or after, it is interesting that none of the subjects in Modigliani’s great nude paintings can be identified as Jeanne. One can speculate about the reasons why. The fact is that Jeanne had no inner inhibitions, sketching herself repeatedly in the nude as she looked into a mirror.

In that year of 1919 the series of portraits, which have shown Jeanne in every possible permutation—hatted, bareheaded, hair up, hair down, hair short, hair long, pose natural, pose self-consciously modeled on the antique—focus increasingly on Jeanne as she grows heavily pregnant and puts on weight. The neck is still swanlike and her glorious hair still full of reddish highlights. But the nose is blunter and even more elongated, she now has a double chin and sits slumped in a chair or a bed, fat-bellied and bulging. These works verge on caricature.

Even so there is evidence that the long-suffering Jeanne had her limits, suggested by a poem Modigliani wrote while they were living together:

comme un poête

qui cherche une rime

ma femme

pour un prêtre

me jette un verre à la tête.

(a cat scratches his head

like a poet

searching for a rhyme

for a priest

throws a glass at my head.)

Could this be an oblique reference to the marriage that never took place?

Modigliani’s great painting, only the second self-portrait known, is considered a late work, probably in the autumn of 1919. He is posed in three-quarter face, with a palette in his right hand, his left resting on a knee. His expression is indecipherable—the art historian Sara Harrison likened it to a mask—and his eyes are narrowed, their sockets blanked out with gray. The autumnal colors of fawns, ochres, and reddish browns, the grayish-blue scarf tied around his neck, provide the elegiac proof, if such were needed, that Modigliani knew how little time was left.

Kenneth Silver writes that the painter took from Cézanne his technique of

thinly applied paint laid down in a repeated hatchwork; the warm/cool palette of earth and sky (or water) tones so beloved of the master from Aix; and even the characteristic and poignant tilt of the head, by which Cézanne evokes a sense of melancholy in the portraits of certain sitters. Yet it is in the tilt as well that we strongly sense Modigliani’s predilection for the Italian Renaissance and especially for the art of Botticelli, for whom the tilted head is a sign of spiritual buoyancy … Italianate too … are both the attenuated linear style and the idealization of the form, which is at the crux of Modigliani’s art.

The perfection of form and the conundrum it posed for an art historian was one of Kenneth Clark’s recurring themes. In “Apologia of an Art Historian,” he argued that an art historian must believe in the greatness of a work before he could understand, let alone appreciate it. “I well remember a time when the Giottos in the Arena chapel meant nothing to me … But I went on looking in hope; and almost without my being aware of it, I found myself experiencing before them the same emotions which I felt in reading the plays of Shakespeare. Through some perfection of form I was enabled to share and to transcend experiences of which, in actual life, my feeble spirit would never have been capable.” The self-portrait and other works by Modigliani, with their increasing subtlety, rigor, and air of inevitability, are witnesses not only to a maturing sensibility but call up an answering echo in the viewer because they are somehow so right. Something rare has been accomplished, and the more one looks the more one finds.

The last known photograph of Modigliani, taken in 1919, shows eyes full of a painful awareness. Yet this extraordinary man, who had days when he could hardly get out of bed, was not only painting at the height of his powers but astonishing his friends by his mental and physical resilience. Sometime during the Christmas holidays, Chantal Quenneville, a friend of Jeanne’s, ran into him at a little all-night café on the boulevard de Vaugirard near Vassilieff’s former “cantine.” He was buying a double helping of sandwiches and consuming them with relish. He explained, “Overeating—that’s the only thing that can save me.” Seeing him arrive at Zborowski’s early on New Year’s Day, so drunk he could hardly stand, clutching a bedraggled bunch of flowers, needing urgently to be put into the nearest bed, Paulette Jourdain could only marvel at his stamina. “It was astonishing how he kept up physically, in appearance, considering the amount he drank and drugged.” The received wisdom was that he drank himself to death. The reverse is the case; alcohol and drugs were the means by which he could somehow keep functioning, the necessary anesthetic, as well as hide the great secret that must be kept at all costs.

To casual observers like the critic Claude Roy, the feverish haste, the irritability, the rages, the search for oblivion could only mean one thing. But in the context of the truth that Modigliani kept hidden so successfully the facts appear in an entirely new light. Noël Alexandre, Paul Alexandre’s son, author of The Unknown Modigliani, said, “The popular version of Modigliani as a drunk, with women and drugs—people have invented a personality that didn’t exist. The one that did exist was so much more admirable. A man who lived his life nobly. An artist, highly original, who looked for another path, different from Picasso, from Matisse. He is unique in his genre, unique in his nobility of intent.”

Alexandre observed that, as he died, Mozart is thought to have said, “I was just beginning to learn how to compose,” and Modigliani could have said the same, “I am beginning to learn how to paint.” He concluded, “Great artists like these go to the end of themselves, and the beauty of their work is a reflection of themselves, after all. They are courageous, to the edge of death.”

“Feeling I would fall, I leaned against a ruined wall, and read: ‘Here lies a youth who died of consumption. You know why. Do not pray for him.’ ”

Like most Italians Modigliani was on easy terms with cemeteries, which for him, as with other European cultures, had the quality of a theme park. Whether or not he took walks in Père Lachaise it is certainly true that he often strolled around the Montparnasse cemetery with Beà and may even have had picnics there. He took the same interest in drama and spectacle as the average Parisian flâneur whenever a particularly grand funeral cortège passed by. He thought nothing of raiding a fresh wreath whenever he needed a flower or two, his favorite offering to a pretty woman. So it is not particularly surprising that he made enthusiastic invitations to friends to go for walks in some nearby cemetery, as he did, raining or not. Whether or not he said that “he liked contemplating death” is a moot point. He certainly knew his own death was not far off.

A more persuasive anecdote is related by André Utter, Valadon’s husband. He states that he, his wife, and friends were dining one night at Guérin’s when Modigliani joined them. He had been drinking but was not drunk and uncharacteristically subdued. He sat down beside Valadon and leaned his head on her shoulder. She was, he said, the only woman who really understood him. Then, huddling close to her, “like a child who is afraid of the dark,” he began to sing a dirge. Jeanne Modigliani, who also wrote about the incident, believed it must have been the Kaddish. This prayer is, according to Leo Rosten, an ancient doxology in Aramaic glorifying God’s name that in time became known as the Mourner’s Prayer. It is recited at the grave of the deceased for eleven months and each year on the anniversary of the death. Modigliani, in other words, was reciting a prayer for himself, mourning his own death.

That night Modigliani stumbled his way home. Somehow he was still on his feet when he was certainly feeling the second-stage effects of tubercular meningitis, with increasing headaches plus the mental confusion which is an indication of the deadly progression of the disease. Anyone could see he was not well but, like Claude Roy, they knew why: he was drinking himself to death. Even as perceptive an observer as Indenbaum was sure of it.

He said that he saw Modigliani a matter of days before he died. He was out and about along the rue de la Grande Chaumière at eight one morning when he heard someone behind him coughing in “a heart-rending manner.” It was Modi, who opened his arms wide; his jaw dropping with surprise and pleasure. They shook hands warmly. Indenbaum said Modi was “very pale, very pulled down and hardly recognizable.” With what was left of his voice he said he was leaving for Italy. It was too bleak and gray in Paris; he urgently needed some sun. Indenbaum believed he was destitute, but that is another common misconception. In fact, for the first time since his arrival in Paris fourteen years before he was actually making some money from his art. In addition to his stipend from Zborowski the sales percentages were rolling in regularly. The month he died he asked Louis Latourette, who was a financial reporter, for some advice about money. It is also known that he sent back the family allowance at about this time, saying he no longer needed it. One of the most painful rumors to arise, three or four years later, was that his family had abandoned him and he had died destitute. That, Eugénie wrote in her diary, was almost more than she could bear.

What is clear is that his friends, who were by now used to shrugging off Modigliani’s exploits, ignored the warning signs. They could well have dismissed him as an alcoholic. On the other hand, they might have learned the truth at last: that he had tuberculosis. If this is so, and it is clear that Zborowski, Guillaume as well, knew what the trouble really was, the news would have spread in the small circle in Montparnasse like wildfire. This is the most plausible explanation for what happened when he was dying and for days left alone.

Beatrice Hastings and Simone Thiroux were nowhere to be found, perhaps for understandable reasons. Moïse and Renée Kisling, who saw Modigliani on a daily basis, did not appear. No sign of Guillaume, Utter and Valadon, Lipchitz, Orloff, Jacob, Survage, Soutine, Brancusi, Zadkine, or any of the subsequent chroniclers, Latourette, Salmon, Carco, Michel Georges-Michel, and all those who would later claim to have witnessed the hourly drama of Modigliani’s final days. Zborowski and Hanka did indeed appear but, as he confessed later, did not realize that Modigliani was seriously ill because, he said in self-justification, Modi was walking, talking, and eating, apparently in the best of spirits, just before. As luck would have it, the painter Ortiz de Zárate, whom Modigliani had met in Venice, was also living at the rue de la Grande Chaumière with his family and could be relied upon to keep him supplied with coal. But he was away for a week and that was the week Modigliani got ill.

The last photograph of Modigliani, 1919 (image credit 13.5)

Not long before he died of cancer in 1982, David Carritt, then fifty-five, whose acumen as a London art dealer was equaled by his erudition and knowledge of the Italian Renaissance, was invited for a weekend. He apologized. He could not go, he said, because friends were about to take him on a voyage to Cythère. This poetical reference to an island off the southernmost coast of Greece, seemingly distant enough to be in another world, is a metaphor for the soul’s ultimate journey. It was celebrated by Charles Baudelaire in his poem “Un Voyage à Cythère.”

Quelle est cette île triste et noire?—C’est Cythère,

Nous dit-on, un pays fameux dans les chansons,

Eldorado banal de tous les vieux garçons.

Regardez! Après tout c’est une pauvre terre.

(What is that sad, dark island?—It is Cythera,

They tell us, a country famous in song,

Banal Eldorado of all the old bachelors.

Look! After all, it is a poor land.)

A voyage as a metaphor for death is so common that it is curious that commentators missed the reference in another anecdote that was told by the Vicomte de Lascano Tegui, an Italian artist acquaintance of Modigliani’s. Tegui recounts that it was a rainy night (as it always is in stories of this kind). Modigliani insisted on joining Tegui and a group of friends who were on their way across town to visit another Italian, a draughtsman. Aware that he was in no state to make the trip, they attempted to dissuade Modigliani. But, trailing an overcoat that he refused to wear, already soaked to the skin, Modigliani could not be dissuaded. So they shrugged and set off. He followed a short distance behind, muttering to himself. They realized how tenuous his hold on reality had become when he stopped in front of a thirty-six-foot monument of a lion and started cursing it as if it were alive.

When they finally arrived at the draughtsman’s quarters they tried again to persuade Modigliani to do something he was determined not to do. At least come inside, they said. He fought them off. He sat down on the sidewalk and was still there several hours later. It was, of course, still raining. Saving such a man from himself is such a thankless task that the wonder is that anyone did anything. According to one report, they managed to bundle him into a taxi and send him back to his studio. Accounts of the incident dismiss as mere raving what happened before he left. Modigliani explained to anyone who would listen that he was seated on a quay on the edge of a miraculous sea. There, coming toward him, was a phantom boat.

Soon after that, perhaps the next morning, Modigliani went to bed for the last time. The legend has him dying on a filthy pallet while Jeanne, stoical to the end, sits surrounded by empty liquor bottles and opened cans of sardines, their only source of food. In other embellishments Modigliani is on a rampage, refusing food, screaming whenever visitors attempt to enter, and refusing, according to Sichel, to see a doctor out of sheer childish pettiness. No one has quite dared to give an imaginary dialogue to Jeanne, who is usually treated as if she was not there.

The now demolished, imposing entrance on the rue Jacob, Paris, of the Hôpital de la Charité, where Modigliani died (image credit 13.6)

The only more-or-less reliable account is contained in a letter Zborowski sent to Emanuele Modigliani after Modigliani died. It is entirely possible that, as is claimed, they ran out of coal and the studio was freezing. Tubercular patients often do not feel like eating. Modigliani had lost most or all of his teeth. Whether he had, as some claim, a set of false teeth at that point is unclear, but when his death mask was taken it is clear he had none. What is known is that he liked a particular Livornese dish of tiny sautéed fish, and sardines might have seemed like the closest equivalent; in any case, they are easy to swallow. On the other hand, Chantal Quenneville, the first to arrive after Modigliani’s death, makes no mention of them. As for empty bottles, one imagines Modigliani would be looking for something, anything, to dull the pain. There would have been continuing headaches, with increasing sensitivity to light, diarrhea, night sweats, trembling muscles, and stomach pains. What he complained of most in the beginning were pains in his kidneys. He had had them before, but this time the pain was acute. Jeanne went to find Zborowski, and he called a doctor, who diagnosed an inflammation of the kidneys. Curiously enough, Keats was subjected to the same myopic medical diagnosis when, as he was spitting blood, his doctor diagnosed stomach trouble. Thanks to Modigliani’s doctor’s almost willful refusal to see the obvious, he struggled on alone. Whether he received a daily visit from the same doctor, as Zborowski claimed, seems doubtful.

The portrait of the Greek composer Mario Varvogli, which was still unfinished on an easel in Modigliani’s apartment when he died early in 1920. Modigliani wrote on it, “Hic incipit Vita Nuova,” i.e., “Here begins a New Life.” (image credit 13.7)

On the sixth day Zborowski “became sick” himself (not explained) and Hanka was sent. Modigliani was now coughing up blood. Again the same doctor was called. He was now considering hospital but cautioned that Modigliani should not be moved until “the bleeding had stopped.” Another bitter piece of bad advice. As they all said later, “If only he had been helped in time …” The bleeding never did stop. Two days after that, Modigliani lapsed into a merciful coma. The third and final stage of tubercular meningitis had arrived.

The most puzzling aspect of these last days is Jeanne’s curious inability to act. True, she had a secret to be kept at all costs and so she might have listened to a doctor making a partial diagnosis without comment, out of loyalty to Modigliani. True, being within days of giving birth, she would have had trouble getting up and down those stairs, but she went to fetch Zborowski and also make refills to Modigliani’s brandy bottle that would have served him as the only available painkiller. It is clear she could, and indeed was, eating something else besides sardines. She had girlfriends she could have called on for help. André was back. Her parents lived close by. Yet she made no move to contact anyone. Restellini believed that she was, by then, completely under Modigliani’s malign control. All his life he had thought of death, philosophized about it, railed against it, and fought to stay alive until he identified completely with Maldoror. In close relationships he was demanding and authoritarian. Loving him would mean giving up everyone and everything for him, as Lunia noted. (“Il éprouva aussi … une sentiment si vif qu’il aurait voulu que j’abandonne tout pour le suivre.”) She was not willing to make that sacrifice. Jeanne Hébuterne was.

Ortiz de Zárate reappears at this point. He writes that he went to see Modigliani after a week’s absence and was horrified to find him in such a state. He had the concierge bring up a pot-au-feu, certainly something Jeanne could have done had she not been so transfixed. He claimed to be the one who summoned another doctor and got the unconscious Modigliani to the hospital. This claim is at variance to Zborowski’s, who implied he had been the one to come to the rescue. “His friends and I did everything possible.”

Modigliani died without regaining consciousness at the Hôpital de la Charité in the Latin Quarter, at 37 rue Jacob on the corner of the rue des Saints-Pères. It was demolished many years ago and replaced by the École de Médicine, but at that time it was a group of buildings with an imposing entrance that encircled a large courtyard and the solution of last resort for the down-and-out, the penniless and starving who were too ill to walk and too poor to go anywhere else. Contemporary photographs show vast wards of fifty or sixty patients. Even that was better than the rue de la Grande Chaumière. The Sisters of Charity who acted as nurses would have provided at least some palliative care as Modigliani sank into death. He died there two days later, at 8:45 p.m., his eyes closed and his half-open mouth twisted to one side, as a drawing by Kisling shows. He was alone. Jeanne must have given the information for the death certificate. She testified that she was his wife.

As long as he could still stand—Zborowski claimed until three days before his death, although this seems unlikely—Modigliani was at work. The painting, unfinished, on his easel was a portrait of Mario Varvogli, a Greek composer with whom he had been out drinking as recently as New Year’s Eve. Its inscription, “Here begins a New Year,” would have been appropriate. Instead he wrote, “Hic incipit Vita Nuova,” that is to say, “Here begins a New Life.”

The biographer of Moïse Kisling, Claude de Voort, echoed the familiar argument that Modigliani’s sudden death took everyone by surprise, which has, on the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary, to be a rationalization. Be that as it may, Kisling, Ortiz, and Zborowski seem to have called a meeting within hours. They sent an immediate telegram to Emanuele Modigliani but there was no hope that he could get a visa in time to attend. So the reply came back that if they would arrange for the funeral he would reimburse them. They should cover Modigliani with flowers. The legend adds they were to “Bury him like a prince.” Charles Daude, the firm of undertakers whose establishment on the rue Bonaparte was nearby, received from Kisling the handsome sum of 1,340 francs. Those were the days when fifteen francs would buy a burial service of sorts and, until recently, Modigliani was living on a hundred francs a month. Given that kind of outlay a floral mountain was practically guaranteed. As for a princely burial, someone somehow got the idea that Modigliani ought to be buried in the famous Père Lachaise, the final resting place of France’s glorious dead in all the arts, and succeeded in getting permission. Only the best was good enough—belatedly.

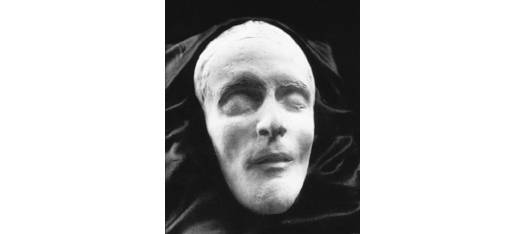

Between his death on Saturday night and the funeral on Tuesday afternoon, Kisling and company bent every effort to send their Modi off in style. Kisling’s uninspired but competent sketch would have been made within hours of his death. Then Kisling and Moricand decided to make a death mask even though, being artists and not sculptors, their knowledge of method was rudimentary at best. They had to act fast because the nuns wanted the body out of the hospital’s amphitheatre and into the morgue; there was always a desperate need for beds. In a rush to hasten the process, and thinking the plaster had hardened, they removed the mold. But it came away in chunks taking, to their horror, bits of skin and hair with it. Lipchitz was called in to rescue the cast and produce a dozen copies in bronze, which he subsequently did. Presumably he or someone else did the necessary cosmetic repair to the corpse.

The death mask that Kisling and Moricand began and Lipchitz finished (image credit 13.8)

The long and winding procession that transported Modigliani’s earthly remains from the rue Jacob to the Père Lachaise that Tuesday has been famously described as attracting a cast of thousands. This seems to be another of those doubtful rumors that has attained the status of fact. Still, to have seen liveried attendants, carts groaning under the weight of flowers, black-plumed horses, and an ornate casket would have been a novelty coming from that particular hospital. No doubt doctors hung out of windows and nuns watched as the cortège swung out of the inner courtyard and made its way down the rue Jacob. No doubt the original crowd of perhaps a few dozen was joined rapidly enough by passersby, who are always curious about a good show. No doubt policemen saluted and held up traffic. It was five miles to the cemetery on the eastern edge of the city and perhaps a few hundred had joined the parade as it swung slowly through the streets. It is said that, as the numbers grew, speculators in art ran up and down the ranks, offering to buy for thousands of francs what no one would pay fifty for while he was alive.

Typical of a fancy funeral of the period like the one which was accorded Modigliani on its way to Père Lachaise (image credit 13.9)

It was said that Zborowski was offered forty thousand francs for fifty pictures, eight hundred francs apiece. It was also said that, as Modigliani lay on his deathbed, the infamous Louis Libaude, known for his predatory abilities, and anticipating the rush, bought up dozens of canvases at rock-bottom prices. Then he went from café to café boasting about the deals he had made. What is true is that at some point during that hectic week Modigliani’s studio on the rue de la Grande Chaumière, with its collection of canvases (perhaps some sculptures as well), in various stages of execution, was cleared of all its contents and that there was nothing left for Modigliani’s heirs to claim. By some further irony of fate, the Galerie Devambez on the Place Saint-Augustin on the Right Bank opened a show of twenty Modigliani paintings—mysteriously acquired, no one knew quite how—the very day of his funeral. There would have been many old friends in the procession: Picasso, Survage, Moricand, Kisling, Lipchitz, Soutine, Ortiz, Léger, Jacob, and many others. The principal mourner, however, was not there. Jeanne Hébuterne was already dead.