Rien n’est beau que le vrai.

—BRANCUSI

I WENT LOOKING for Modigliani’s grave one morning on the first of May, a public holiday. It was raining fitfully, the sky was leaden, and against the stone grays, metallic blacks, and feathery greens, red umbrellas bobbed up and down like so many props from Les Parapluies de Cherbourg. Unlike that famous film the actors in this scene were not singing their lines but there in their hundreds, buying tiny sprays of lilies of the valley or splashier flowers in rapturous bundles, jostling and chattering. I had not realized that the famous cemetery of Louis XIV’s confessor, Père Lachaise, had been built on what was once his own rolling hillside overlooking the city. The idea that what had become a cemetery was still a park in disguise had taken hold and become engrained in a happily haphazard way. All that was needed now was a riverbank, a few picnic baskets, and an accordion at the gates to turn the arrival into Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte.

I found Modigliani at length in one of the outer alleys, where single slabs of stone had to satisfy less wealthy families bidding for immortality. He was in the Jewish section, placed next to a comedian called Maurice Nasil, and next to a small grove of arborvitae. Someone had placed a bouquet of white daisies upon the grave, secured with aluminum foil, and someone else, a cryptic arrangement of small stones and twigs. I suspected a disappearing group of young Americans in blue jeans and hooded jackets. I was reflecting on the irony that this unknown artist had been catapulted into eternal prominence by the circumstances of death, one he would have been the first to appreciate. Someday, a young man in blue jeans would come along and place a talisman of stones and twigs in a secret message that (he knew) a dealer in esoteric mysteries would understand and appreciate.

I thought, too, of Modigliani’s death mask, which did not resemble him or even the drawing Kisling made hours after he had died. The sunken cheeks and elongated jaw—this “half-ecclesiastical patina of authority,” as P. D. James wrote—had made a mockery of the belated attempt to preserve a likeness. In his journal, Odilon Redon observed that to enter these cold and silent alleys and contemplate the deserted tombs gave one a sense of spiritual calm. But, if others had found such calm, I could only think of the hollow mockery of the mask, which seemed to sum up and exemplify the persistent distortions of the Modigliani legend. How could such a memento mori have anything to do with the vibrant, energetic man it supposedly represented? How could anyone have thought, when Modigliani died and had to be buried by the friends who had deserted him, that their hypocritical eagerness to “cover him with flowers” would atone for their betrayal? They might as well have tipped his body over the side of a cliff and let scavangers do the final honors. How cruel his life was, Zborowski concluded.

There remained the apartment on the rue de la Grande Chaumière. Some atavistic impulse kept me returning to that small, pretty street. Perhaps I could commune with the apartment’s ghosts or at least imagine what it had felt like to live there. But I could not get inside. When Kenneth Wayne visited a few years before the street door had been open. Now it was protected with a lock to be opened by a special code and I did not know where to begin. But then Michèle Épron, my Parisian friend, found she could get an introduction to an artist who lived there. With the appointment went the door code.

Charles Maussion was living in a second-floor apartment directly below one of the rooms that had once housed Modigliani, his studio. We were ushered into what seemed like an all-white room crowded with mostly all-white canvases. Our host was of medium height, wearing glasses, a crewcut, and a beard, a former mathematician and philosopher who had lived there for fifty years and never left because the light was so perfect. His apartment had once belonged to Survage and although not identical to Modigliani’s, often appeared in films because it was neat and well kept, in contrast to the latter’s. This had not prevented numbers of intrepid visitors from climbing the stairs and trying to get into Modigliani’s old quarters. One of them was Patrice Chaplin, author of Into the Darkness Laughing. She related she had tried to encourage a companion to pick the lock with a credit card, then heard footsteps coming toward the door, stop, and start again. Supposedly, no one was in the apartment. Was it haunted, Maussion was asked? He smiled dismissively.

By then I knew, thanks to interviews conducted by John Olliver, that among those in the background when Modigliani died was Waclaw Zawadowski, a penniless Polish artist. Later, he boasted that he had moved in so soon after the funeral that Modigliani’s last portrait, of Mario Varvogli, was still on his easel and drawings littered the floors. Fairly soon after that, Nina Hamnett moved in with him. Her memoir, Laughing Torso, is considered highly unreliable and at least one author, Simon Gray, has called it “an alcoholic shambles.” So one has to view with caution her story that she found a one-hundred-franc note stuck inside one of Modigliani’s books on philosophy, proving (to her) that Jeanne Hébuterne would hide their money to prevent Modigliani from spending it all. They helped themselves to Modigliani’s shelf of books, reading French classics to each other at night as they sat around Modigliani’s battered table, warming themselves beside the stove painted by another acquaintance, Abdul Wahab. Perhaps it was true, as “Zawado” told Olliver, that he found a way to make money out of Modigliani’s memory one day when an American came to visit. Hearing that the palette hanging on a wall had belonged to Modigliani, the visitor immediately bought it. Sometime later another visitor noticed another palette, well smeared with the plausibly hardening remains of Modigliani’s colors, hanging on the same wall. As soon as he heard the story he bought that one as well. Zawado’s business in Modigliani palettes continued at a satisfactory pace.

Maussion’s belief that the apartment was uninhabited, however, was somewhat out of date. It was true that the apartment had been little used in the intervening eighty-odd years. At one point the rooms, at right angles, each about twenty-five or thirty feet long and some eight or ten feet wide, were divided into two apartments and rented separately. One had never been used; the other was used occasionally as an office. All that had changed recently.

One evening Marc Restellini and I went visiting the agent for change, Godefroy Jarzaguet, a direct descendant on his mother’s side of the Delaunes, who had owned the building since it was constructed following the demolition of the international exposition in Paris of 1889. So the Delaunes had been the landlords when Modigliani lived there but Jarzaguet had known very little about Modigliani and implied had not thought much about him, either. He was looking for an apartment and that top-floor two-room space was very tempting. Besides, it was owned by his grandfather, Roger Delaune. If he was willing to do the work of restoration, could he rent the apartment? His grandfather said yes.

The long, narrow, boxlike studio apartment on the rue de la Grande Chaumière (image credit bm.1)

“Everything was a mess,” he said. “When you came in there was a tiny hall with two doors, one coming left into the living room, where a stove sat on a small marble stand. This was the side that was rented. The other went straight ahead into what had been Modigliani’s studio and since there was no source of heat, nothing had ever been done to it.”

The apartment, besides having no heat (apart from the stove), had no water either until somebody brought up a toilet in the intervening decades. Jarzaguet immediately removed the hallway and one of the doors, making every effort to return the apartment to its original state. Even so, a kitchen area had to be introduced and a bathroom partitioned off. The studio’s floor had completely disintegrated; new supports had to be put in place and pine flooring installed. The ceilings were dropped about six inches and the walls brought in for insulation purposes. New, insulated windows were installed on the bedroom side. New cupboards and bookshelves followed. All of this took a couple of years. How did the materials get upstairs? “Most of them came up on my back,” Jarzaguet said.

The derelict apartment on the rue de la Grande Chaumière before being renovated in 2007 by Godefroy Jarzaguet (image credit bm.2)

The far corner of what is now a bedroom faces another building that is directly on the street. By coincidence it is at eye level with an apartment that was being rented by Alexandra Marsiglia; her bathroom, in fact. Jarzaguet would be working and she would be watching at her window and smiling. He would smile. They would meet on the stairs or the hallway at street level and smile. Still, neither of them said a word. He was already a little in love with her. “I had this fantasy about her,” he said. “I imagined her life. I knew she lived alone as a student but that is all I knew.”

Then one day he was on his roof deck sunbathing when she opened her window and called out. “How do you get up there?” He invited her to his recently finished apartment. When she arrived he showed her a small, unobtrusive trap door in his living room ceiling and a handy rope ladder. They went out to dinner that night. She was studying art history and one of her creations in décollage now hangs over the dining table. There are Andy Warhol soup cans over the sofa and plenty of art books on the shelves, but no sign of a Modigliani, let alone a Hébuterne. He talks about heating, lighting, and construction. She talks about the brief, last hours in the apartment shared by Amedeo and Jeanne, and the legend that the apartment is haunted. “After all,” she says, “nobody actually died here,” which is true.

The bedroom faces a blank wall where a Virginia creeper has grown upward until it is almost at eye level. Godefroy said, “It’s so quiet here. You could be at the end of the world.” Sometimes tendrils of mist cling to the chimney pots. Or, on a starry night, the moon rises up over the bedroom, in gold and red. “It’s magnificent.” The fact that the renovation of this particular apartment led to a marriage—they had just returned from their honeymoon in Sicily—seemed serendipitous, almost poetic justice. “I feel,” he said, “I have brought it back to life.”

In Modern Art, Meyer Schapiro’s seminal work on art of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Modigliani’s name does not appear. He is not even a footnote in The Visual Arts, a History, by Hugh Honour and John Fleming, that otherwise learned and authoritative account of the major historical trends and their minor tributaries. In Great Private Collections Douglas Cooper, the persuasive author and critic, limits his praise for a Modigliani portrait to its elegance of line and retrogressive references to the Sienese art of the trecento. Kenneth Clark’s monumental study The Nude makes no reference to Modigliani’s masterful studies of the female form despite the fact that the author clearly admired him at an early age. In the catalog for his enormously successful exhibition of 2002, “L’Ange au Visage Grave,” Marc Restellini wrote about the paradox of Modigliani’s vast popularity and his representation in discerning private and public collections, versus the disdain historically shown for his work by academic and art historical circles. “The universities where Picasso or Matisse are much studied deem Modigliani a facile painter devoid of innovation,” he wrote.

Part of the problem may have been that, Restellini added, “Forgeries appeared almost from the day he died.” Another issue had to do with the artist’s stubborn insistence on his difference. He did not follow Fauvism, Cubism, Surrealism, Futurism, or any of the other “isms,” making him harder to categorize. He was another of those unclassifiable characters like Stanley Spencer, Henry Fuseli, Albert Pinkham Ryder, or even William Blake, who have no effect upon chroniclers in the world of art. With apologies to Robert Hughes, there was nothing shocking about his newness. There were no distorted features, à la Picasso, no Robert Ryman white on whites, no Mondrian blocks and diagrams, no canvases pulsating with color, like Mark Rothko’s. There was only the perverse insistence of an unknown artist putting down paint on canvas as if to say, “This is what I see.”

Well, as Cocteau used to say, “Ne t’attardes pas avec l’avant-garde,” and that Modigliani certainly never did. His vision was cool without being clinical, elegant without being mannerist, an art of harmony, balance, and Renaissance humanism. In an age when Beauty, that reigning ethos, had been pronounced dead, Modigliani lived for it. When shape was being deconstructed, he exalted it. When the human form divine was being belittled, even uglified, he celebrated it. His very existence as an artist challenged the theoreticians of the time. It is interesting that long before American reviewers and critics, or French (with the possible exceptions of Warnod and Carco) discovered his work the British, and particularly Roger Fry, recognized Modigliani’s importance. Fry shared the same passions for the Italian Renaissance, African sculpture, and Cézanne; a climate of intellectual open-mindedness, along with a tradition of artistic independence, allowed Fry to admire those very qualities being dismissed elsewhere.

Werner Schmalenbach wrote that if the criterion was the extent of Modigliani’s influence on the art of his own time, “the answer has to be that there was no such influence.” However, if one judged by Modigliani’s artistic impact, that had continued to this day, “and this is the impact that counts, since it rests solely on the individuality of the artist and his work.” It might even be considered an advantage to be outside the ruling trends, the implied moral of Cocteau’s maxim, since whatever is never “in” is never exactly “out,” either. “This independence,” Schmalenbach wrote, “which never makes him look merely dated, is undoubtedly part of his greatness.” Another part of that greatness, as Restellini showed, had to do with Modigliani’s “metaphysico-spiritual” beliefs. “Behind the legend of the sole ‘artist maudit’ of the twentieth century stands a visionary artist with an extremely radical philosophical conception of his art.”

Authors have marveled at the contrast between the confidence and control of Modigliani the artist versus the chaos of his personal life and concluded that there is no connection. I have suggested that his lifelong, losing battle with tuberculosis was one aspect of his art’s covert subject matter and that the psychic scars he endured found a kind of sublimation in the expression of his mystical and philosophical beliefs. Another was the theme of the mask. Coherent and guiding principles can be glimpsed in his life as well as his art, despite appearances. In short, the apparent chaos of his private world threw an essential veil over the truth, buying time for him to go on developing as an artist. He hid behind this façade with such success that he fooled most of his contemporaries and a great many people since. He was prepared for life to be a battle. Perhaps he also thought, like E. M. Forster, that it was a romance, and that its essence was romantic beauty.

One of the first art historians to divine the man behind the accepted view of Modigliani was John Russell. Writing in 1965, he observed, “Where myth and anti-myth take over from history, as has been the case with Modigliani since the day of his death, it is never easy to cut back to incontrovertible fact. It may even be unpopular, for the notion of Modigliani’s life as a chaos of unrelated inspirations is a fancy widely cherished.” He continued, “Modigliani had great natural gifts, admittedly; but they were not at all precocious … and only a profoundly serious and coherent artist could have brought them to the degree of fulfilment which he attained in the months before his death.” His art, Lionello Venturi wrote, could be seen in two aspects: “as an art of the free imagination in so far as his poetic vision leads him to transmute natural forms, but also as a very human art that bodies forth a world in which the life of men is depicted in its essential purity and grandeur.”

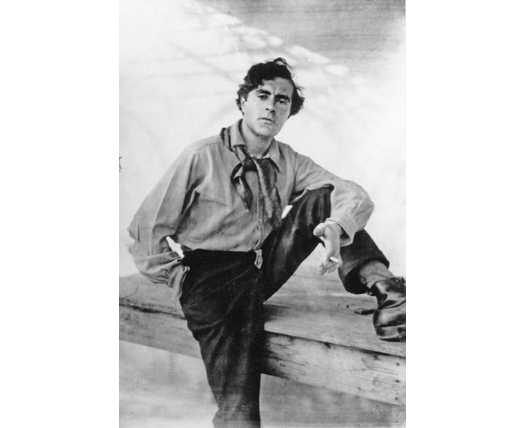

Modigliani in 1909, wearing the “artistic” style he affected shortly after arriving in Paris (image credit bm.3)