APRIL 8, 1917

VIMY RIDGE, FRANCE

“Please do not take this as a complaint,” Thomas said to Jake. “But I do not like this at all.”

“Because you have to stop singing to complain,” Jake said, “I’d be happy if you kept complaining. Also, you are so off tune, I think it is cruel to make the horses listen to you.”

Each of them were holding the reins of a packhorse. The horses carried canvas bags, one bag on each side. Each bag held four massive shells that looked like gigantic bullets. Two shells together weighed as much as a full-grown man.

Just beyond them were the massive guns that fired those shells. It took a team of twenty men to load those guns. And there were nearly a thousand artillery pieces firing at the enemy.

Jake and Thomas were in a group of hundreds of soldiers who had been given the job of leading the packhorses from the rail lines to the guns.

Jake shifted his feet. He was standing in muddy water. His leg was sore from where the bullet had torn through his thigh six weeks earlier. He was covered in slime from mud. He itched from lice. His hands were cold.

“Besides,” Jake said, “it is just another day in paradise. Why would any of us complain?”

“I just said it was not a complaint. I said—”

Thomas did not get to finish his sentence. A new barrage of shells thundered. It had been like this for seven full days. Thousands of shells each day and night rained down on the enemy trenches. Thousands!

Soon, the Canadians would advance. But until then, the enemy would not be given time to eat or sleep or even time to shave. They would be getting tired from constantly being ready for battle.

In the short silence that followed, Thomas finished speaking. “What I do not like is how horrible it is for these horses. You and I had a choice. We volunteered. And we can speak when we need help. Not these horses.”

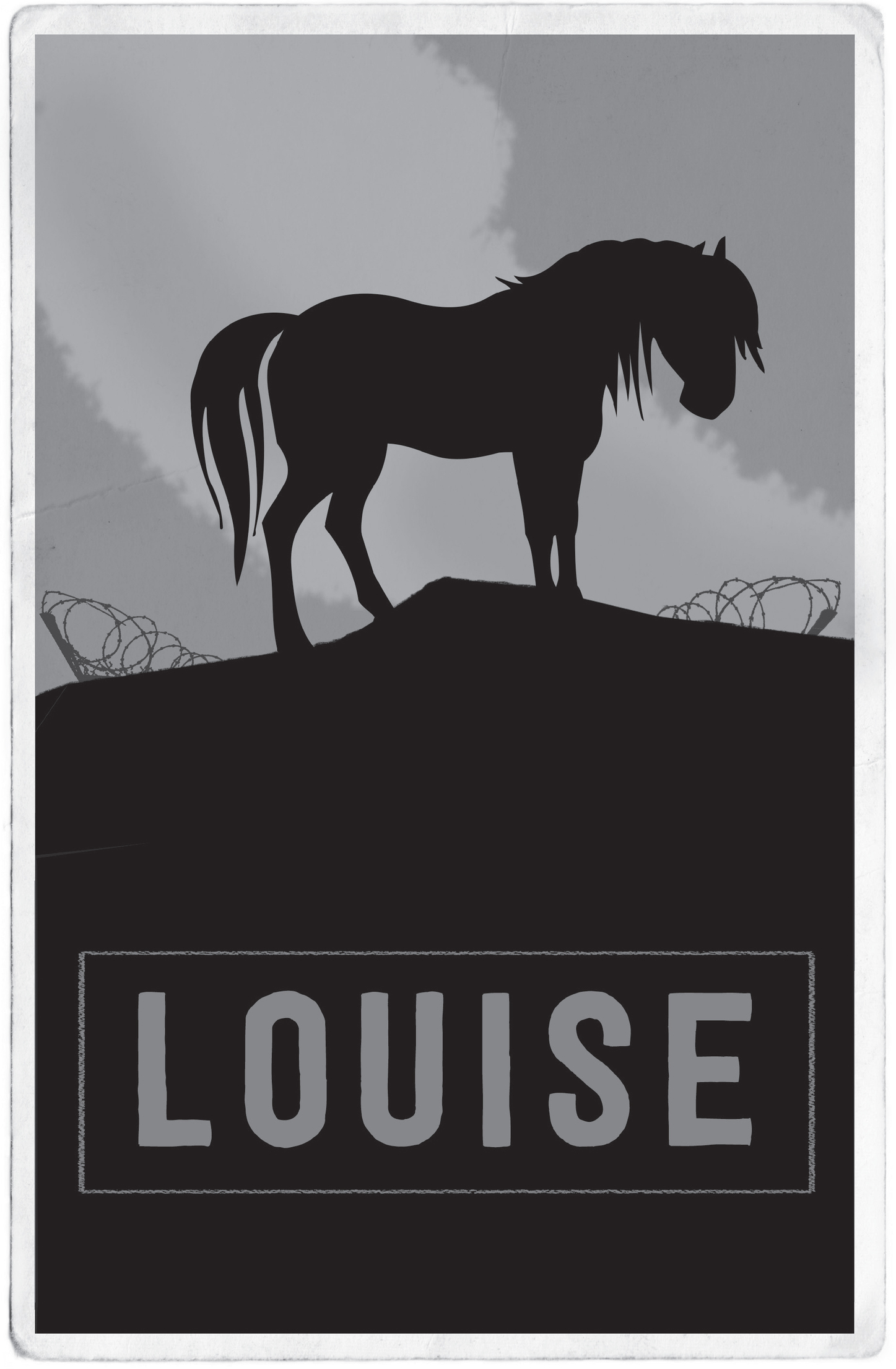

Thomas pointed at his horse. “Louise here, she—”

“Louise?”

“She reminds me of my aunt Louise. Very patient. We can pick off the lice from our skin, but these sores? Mange. From mites. She must be in constant pain, but she does not fight her load or kick at me.”

Thomas ran his hand along her ribs. “Have you noticed each day we have to cinch the straps another hole? These horses are starving.”

Thomas lifted Louise’s front foot. “This hoof. It is like all the others on Louise. You are a farm boy. You know what that is. This horse is miserable.”

The hoof was splitting because it was constantly wet. Jake sighed. “Canker.”

Thomas knocked on his helmet. “I have protection. This horse does not. Horses are shot at and shelled and hit with poison gas. When this war is over, I hope they are given good treatment. They deserve it.”

Before Jake could reply, another huge round of shells thundered from the big guns. It was too loud to hear conversation, even if someone had shouted in his ear.

As it turned out, someone was trying to shout in his ear.

Jake felt a hand on his shoulder and turned.

Charlie’s face was filthy with mud, but he had a wide, white grin.

As the thunder lessened, Charlie said. “Hey you two! Lieutenant Norman sent me to look for you. The doctors cleared you to join the platoon for active service. We all cheered when we heard. You can come back with me straight away.”

“No,” Thomas said.

“No?” Charlie echoed. “In the hospital, you said you would do anything to get back to the fight.”

“That has not changed,” Thomas said. “But these two horses depend on Jake and me to get them back for the night. Then we will join the platoon.”

—

“This is like mail call for Thomas,” Lance Wesley told Jake. “Chocolates for him. Wagonloads of feed for the horses. Even some barrels with oats.”

They stood in a field, surrounded by hundreds of other packhorses and hundreds of other soldiers.

There was only a half hour of sunlight left. Wind was picking up with the first traces of sleet. None of them commented on the weather. In Canada, they had faced much worse without complaint. They took pride in this, knowing the British and French soldiers marveled at a Canadian soldier’s toughness and endurance.

Lance’s hearing had returned, but he had an obvious limp that kept him from active duty, so he had not been cleared for battle.

Lance ran his hand along Louise’s right front leg, feeling for injuries. He cared very much about all the horses.

He frowned. “Anywhere else and any other time, these horses would be getting rest and feed. I am glad, Thomas, that you donate all your chocolate and treats for the horses, but they need more than that.”

“I am very aware of this,” Thomas said. “I wish I could do more.”

Lance said to Thomas, “What’s your secret? Why do you get so many packages with chocolate from so many women?”

“There is no secret,” Thomas said. “It should be obvious. A fine warrior like me turns heads anywhere.”

“Either that,” Jake said, “or a fine warrior like him is very good at writing letters.”

“Letters?” Lance asked.

“Letters?” Thomas said, trying to sound innocent.

“Thomas,” Jake said, “I found one of your half-written letters where you had dropped it. I put it back in your notebook while you were asleep. Of course, I read it first. Such sweet words to a lady in London named Nancy. And of course, I then looked for other letters in your notebook. And found other names.”

“Oh,” Thomas said. “Those letters. I only do it because it makes all of them so happy to help a poor, lonely soldier. It is a sacrifice, but someone must do it.”

Lance said, “I don’t understand.”

“British newspapers,” Jake said. “There’s a column called ‘Lonely Soldier.’ It’s for soldiers at the front without friends or relatives who write to the newspapers and give their names. Women in England send food and candy and letters to cheer up the lonely soldiers.”

Thomas grinned at Lance and Jake. “It was one of your people who said that the pen is mightier than the sword. I am happy to learn your ways when it is convenient or useful. After all, that is why I use army socks in Cree moccasins.”

Lance laughed. “I’m going to miss you, both of you. It’s been nice to have a couple of weeks with mates from the platoon. But I understand why you want to get back.”

Soldiers in a platoon were closer than brothers. They fought hard in battle because they did not want to let down their brothers in arms.

Jake knew that Thomas had an extra motivation, however. Thomas believed if he returned to Canada with ribbons of honor that no one would deny his right to equal citizenship.

“I do want to get back,” Thomas said. “But first, Louise deserves a fine meal. Oats you said?”

Lance nodded. “Over there.”

“Thank you.” Thomas grabbed an empty feed bag and headed to the barrels.

“Any idea when?” Lance asked Jake.

Jake shook his head. Everyone knew that the Canadians were preparing to attack Vimy Ridge. Even the enemy troops knew. The only question was when.

To fool the enemy, General Byng had ordered extra heavy barrages of shelling to come without warning. The first few times, the enemy troops had prepared for a charge. But now they were exhausted after days of shelling. The enemy officers had difficulty getting their men in position because the men believed each new barrage was just a false alarm.

“And how is your leg?” Lance said. “Don’t lie to me. I’m not your doctor.”

“It could be better,” Jake said. “It’s the same with Thomas. Another week with the horses would be good. But any time we will get the word. So we can’t wait. I’m sorry you can’t join us.”

Lance started to nod, then his eyes widened and he looked past Jake.

“What the…”

Jake turned.

He had never seen Thomas run so fast. His friend pushed past a few other soldiers and then dove into a man who was lifting a feed bag of oats to a horse farther down the line.

Both of them tumbled into a ball.

And within seconds, four soldiers stood above Thomas, their rifles pointed downward.

“Stop right there!” one of the soldiers yelled.

Jake began to sprint in his friend’s direction. He didn’t feel any pain in his leg. Only fear for his friend.

—

When Jake reached his friend, Thomas was still on the ground, with rifles pointed at him.

“Jake, take that horse by the halter,” Thomas said. “Do not let her eat those oats. Look for nails.”

Jake didn’t ask why Thomas wanted him to do this. He had learned to trust his friend.

Jake took the horse by the halter and lifted her head away from the ground.

Tiny nails were scattered on the ground among the oats.

Jake turned to the soldiers. “Look at this. If the horse had eaten those oats, the nails would have torn apart her stomach.”

One of the soldiers glanced at the nails on the ground. He lowered his rifle and picked up the feed bag that had fallen. He shook oats and more small nails out of the feed bag.

This soldier spoke to the others. “Let him stand. He was saving the horse.”

As Thomas stood, he said to the man he had tackled, “I found nails in the barrel as I was getting oats for my horse. I did not know if you would listen in time if I yelled for you to stop feeding your horse. I am sorry. I saw no other way but to tackle you.”

The man did not answer. He was shaking as he rolled onto his knees. Beads of sweat covered his face.

He stood.

He punched Thomas across the cheek.

Thomas rolled his head with the punch. He rubbed his cheek. “I take it then that you do not accept my apology.”

“I could have stopped the war,” the man said in a choked voice. “I could have stopped the war!”

The man dropped to his knees and tried to gather the nails on the ground. “Help me. Help me. I can’t stand the noise anymore. We need to stop the horses from taking shells to the guns. If we kill all the horses, the war will stop. Help me. Help me.”

The man was frantic. He began to sob.

Jake let out a long sigh of sympathy for the man. Obviously, killing all the horses would not stop the war, but this man just as obviously believed it. Jake suspected the poor man was shell-shocked. This happened to some soldiers after enduring the strain of constant battle.

Jake looked at the other soldiers. “Can you take him to a doctor and ask them to examine him? My friend and I will check the rest of the feed to make sure there are no more nails.”

—

It took Jake and Thomas a full hour of walking through the muddy water in the maze of trenches to reach the Storming Normans platoon. By then, night had settled, but the wind had not, and it drove sleet over the top of the trenches.

The welcome from Lieutenant Norman was warm, however.

Not as warm as from Colonel Scruffington. The dog stayed in full salute for one minute, even after Thomas said “at ease.”

“Good to see both of you,” Lieutenant Norman said. “I know it’s been a long day, but orders could come at any time for the attack. Now that you are back we need you to memorize your portion of the map.”

This was not a surprise to Jake. It was common knowledge among all the soldiers that each division leader had a thick binder with complete plans of the attack. This had been broken into many small pieces, so that every section of six to nine soldiers had their own detailed map. The maps were marked with exactly what the small group needed to accomplish.

It made Jake feel like he was trusted by the commanding officers and that they felt he was smart enough to do what needed to be done.

He remembered what Major McNaughton had passed along from General Byng just before giving them medals of honor. I want soldiers with the discipline of a well-trained pack of hounds. Soldiers who will find their own holes through the hedges. I’m not going to tell them where those holes are or how to get through them. I want soldiers who can find those holes themselves and get through those holes their own way. Soldiers who will never lose sight of the objective as they do it.

Down in the trench, they were safe from the wind. They studied the maps by candlelight.

“We’re going to be able to do this,” Thomas said. “I can feel it in my bones. All four of our Canadian divisions together for the first time? We’re going to do what everyone else thinks can’t be done.”

Jake felt that pride too. The British had failed to take Vimy Ridge. The French had failed to take Vimy Ridge. But he and the rest of the platoon had spent weeks and weeks training for this. They would fight for Canada. More importantly, they would fight for each other. Jake was glad to be back, even though he knew it would be dangerous.

Lieutenant Norman stopped by again.

Colonel Scruffington stood with his shoulder pressed to Thomas’s knee as if he was afraid Thomas might go away again. That made Jake sad. Thomas was about to go away: into battle.

“Are you both good with what you need to do when we go? You have the instructions and map memorized?”

Jake and Thomas nodded.

“Good,” Lieutenant Norman said. “When we get the call to go, I won’t have time to say much except do your best. So now is when I have to remind you of the most critical part of the attack. And this comes directly from General Byng, so I need you to listen as if your lives depend on it. Because your lives do depend on this. Ready?”

Jake and Thomas nodded again.

Lieutenant Norman said, “The barrage of shells is going to be like a moving curtain in front of you. This curtain is going to be your protection from the enemy. It means when you go over the trenches, you have to be like a railroad train. Exactly to the second. If you move too quickly, you’ll run into that curtain of explosives, and you’ll be dead. If you move too slowly, the enemy will recover before you can pounce on them in the trenches. That’s why we taught you the Vimy Glide. Tell me you both understand.”

Jake and Thomas nodded for the third time.

“Not good enough,” Lieutenant Norman said. “You need to tell me you understand. Each of you.”

“I understand,” Thomas said.

“I understand,” Jake echoed.

“Good then,” Lieutenant Norman said. “You need to do one last thing before sleep. Write your letters to your loved ones and hand them to me. I’ll pass them down the line for safekeeping.”

Jake knew exactly what that meant. He leaned over and scratched Colonel Scruffington’s head. Some of them might not make it home.

He was far less afraid of dying than he was of letting down his fellow soldiers. He wanted to be there for Thomas and Charlie and the others. Jake belonged to the platoon.

—

Louise belonged to the herd. Not just a herd of other creatures like herself. In the herd were the two-legged creatures that made soothing sounds as they patted her side and rubbed her nose.

Louise felt safe in the herd, even in the dark. Even when she was awake at a time that she normally slept.

There was wind and sleet as she plodded through mud. She felt the itch of her hide and it hurt to walk. Her belly was tight and she wished she could drop her head and find thick grass. She felt the tremendous weight on her back of the load that had just been placed by those two-legged creatures. But her pain mattered less than loyalty to the herd.

There had been one two-legged creature in particular who led her by the halter, and the soothing sounds that came from this creature were a particular rhythm that she enjoyed, but he was not with her anymore.

Someone else held her halter. Someone else guided her. Something about the smell of this creature’s skin said that tonight there was an urgency to making sure the herd moved forward.

Louise could hear the sounds of hundreds of others in the herd, plodding forward in the dark in the mud.

She knew where they going. They had gone there many, many times before. They were going to the smell of the big iron and the smell of bitterness from loud sounds, where the load would be taken off her back. Then the creature beside her would lead her back to where they had started, and another load would go on her back.

It was strange to do this at night, but Louise was part of the herd. Louise felt safe in the herd. Louise felt loyalty to the herd.

Louise moved forward in the night.

—

The wind had picked up in the night, and the sleet had thickened. Jake and Thomas and Charlie stood in the trenches with the rest of the platoon, waiting for time to tick down to precisely 5:30 a.m.

An hour earlier, Lieutenant Norman had tapped on their shoulders, telling them it was the morning for the attack. Every Canadian soldier able to fight was ready. Every single soldier! Jake knew he would never forget the date: April 9, 1917.

Dawn for them did not come gradually.

To the second, at 5:30 a.m., the pitch-black night sky blossomed into a brightness so intense that Jake could have read a newspaper. A split second later came the sound that shook his entire body.

It was as if twenty locomotives had collided directly in front of him. He’d thought the previous seven days of shelling were loud, but this was as if the very earth had been struck by a meteor. Jake had a quick vision of the lines upon lines of packhorses that had served to move all those explosives from the trains to the artillery and realized that the shell-shocked soldier had been right. Without the packhorses, there would have been no attack.

At the first of the explosions, the Canadian trenches erupted with thousands upon thousands of soldiers and Jake scrambled forward with them.

There was no time to give in to any kind of terror. It was too loud to be afraid. It was too bright to be afraid. It was nearly impossible to even think.

But because of the weeks of training, Jake found that it was almost as if his body took control, and he found himself gliding forward with the exact rhythm of all those times under the stopwatch. One step every two seconds. No more. No less. One hundred yards every three minutes.

It was almost as bright as daylight. Just in front of him, a sheet of explosives came down, like someone behind him was shooting a stream of water over his head and he could almost reach out and touch the spray as the water landed.

Except this spray consisted of the largest artillery bursts ever fired in the history of all mankind. He glanced left and glanced right. There were clumps of soldiers as far as he could see, all marching with determination behind that protective sheet of explosives.

Few men were falling. The driving sleet was at their backs, making it even more difficult for the enemy to see what was happening behind the approaching barrage of explosions.

This barrage was overwhelming to the point of being supernatural. Despite the advantage of fighting from a trenched position, no army in the world would have been able to deal with the barrage. Their enemy could not shoot, not when it had to cope with the shaking of the earth, the thunder that vibrated their bodies and the massive explosions that crept closer and closer at the exact pace of one hundred yards every three minutes.

Jake concentrated on his pace. One step every two seconds. One step every two seconds. One step every two seconds.

The map that Lieutenant Norman had given him was etched in his mind. Jake knew where to go and what to do when he got there. Thomas and Charlie and the rest of the platoon were by his side. Today was the day.

One step every two seconds. Follow the curtain of explosives. One step every two seconds. The Vimy Glide.

They reached the enemy trench, and right at that moment, the barrage that had ripped apart those trenches stopped.

To his left and to his right, up and down a ridge that was nearly ten kilometers (6 mi.) long, soldiers like Jake and Thomas and Charlie cut their way past the barbed wire, swarmed machine gun posts, dropped into the trenches and chased down the enemy.

Vimy Ridge belonged to them.

One of the most crucial elements to taking Vimy Ridge was moving thousands of tons of armament.

For this reason, the packhorses were almost as important as the soldiers. Patiently and under horrible conditions, the animals steadily brought 42,500 kilograms (93,700 lb.) of ammunition to the front lines—every single day! During the buildup to the battle and the battle itself, the eventual total reached 38 million kilograms (84 million lb.).

For the entire Vimy Ridge operation, then, it took the equivalent of a line of dump trucks seventy kilometers (43 mi.) long to deliver what was needed. While the trucks of that era were capable of moving ammunition, the mud and the poor condition of the roads were too much of an obstacle. The packhorses were so vital that, without them, attacking Vimy Ridge would have been as much a disaster for the Canadians as it had been during the previous failed attempts by the French and British. Since a healthy packhorse can carry about 20 percent of its body weight, a line of all the horses it would take to carry this load would stretch 1,340 kilometers (833 mi.), nearly the distance from Ottawa to the coast of Newfoundland.

SHELL SHOCK

Imagine the physical toll war would take: sleepless nights, fatigue, injuries. Now imagine the mental toll: intense and constant bombardment, noise, danger and the knowledge that you or your comrades could die at any moment—or be responsible for the death of a similar solider on the opposite side.

During World War One, some soldiers began to report symptoms typical of physical head injuries, including amnesia, headaches, dizziness, tremors and a high sensitivity to noise. Many of these soliders were unable to reason or sleep or walk or talk. This was puzzling at first, because the men had no physical wounds to the brain.

Eventually these symptoms were recognized as a mental illness brought on by the stress of combat. Called shell shock then, and later, in World War Two, combat stress reaction, the brains of the affected soldiers would do strange things to try and make sense of the horrors of war.

Soldiers showing symptoms were taken away from the front line as soon as possible. For short-term shell shock, a few days of rest were often considered enough of a cure and soldiers were sent back to the front. Other soldiers, however, never overcame the illness. Ten years after the war, 65,000 veterans were still in treatment for it, and nineteen British military hospitals were totally devoted to treating those cases. Although not all soldiers were diagnosed with shell shock, all soldiers left the war changed—the brutality of what they experienced and witnessed meant that no soldier escaped unscathed.

THE WEEK OF SUFFERING AND THE ROLLING BARRAGE

5:30 came and a great light lit the place, a light made up of innumerable flickering tongues, which appeared from the void and extended as far to the south as the eye could see, a light which rippled and lit the clouds in that moment of silence before the crash and thunder of the battle smote the senses. Then the Ridge in front was wreathed in flame as the shells burst, confining the Germans to their dugouts while our men advanced to the assault.

—Private Lewis Duncan to his aunt Sarah, April 17, 1917

In the last lead-up to the attack on Vimy Ridge, there were three important preparations taking place. First, General Byng made it his goal that every soldier knew the plan of attack. This way they would be able to continue to fight no matter what—even without the guidance of officers. They all knew the plans, just not when the attack would come.

The second major preparation was digging tunnels beneath the German lines. Soldiers set up explosives to be detonated when the attack first began, which took extensive mining operations and tunnel systems with tracks, piped water and lights.

With all this in place, there was still a final part to the strategy before the attack could begin: the armament brought in by packhorses.

Spread over the course of a week before the attack, the Canadians began a massive barrage of shelling on the German trenches. With the constant bombardment, the Germans could guess a major attack was coming, but they could not know for certain when. The shelling was also designed to keep the Germans from sleeping, and over the course of those seven days, more than one million shells bombarded Vimy Ridge. One million! This generated numerous false alarms on the Germans side, and the barrage ensured that the enemy soldiers were tired to the point of exhaustion even before the attack began.

It was such an effective ploy that the Germans have called this softening of their forces “The Week of Suffering.”

The Vimy Ridge attack itself began at 5:30 a.m. on Easter Monday, April 9, 1917. At that precise moment, another barrage began, and 20,000 Canadian soldiers, each carrying up to 36 kilograms (80 lb.) of combined equipment, jumped out of the trenches into snow, sleet and machine gun fire.

As the soldiers crossed No Man’s Land, they were protected by a rolling barrage, the reason that they had trained so long to perfect the Vimy Glide: directly in front of them, like a moving waterfall, the falling shells served as a screen and as protection.

THE BATTLE OF VIMY RIDGE

In those few minutes, I witnessed the birth of a nation.

—Brigadier-General A.E. Ross, following the war

While most of the battle was won on the first day, from the opening barrage on April 9, 1917, the battle for Vimy Ridge lasted until April 12, 1917. It was the first time that all four Canadian divisions battled together. Trained to improvise in pursuit of a well-established goal and to understand what was ahead of them, some individual soldiers were able to force surrender of groups of Germans in their well-protected trenches, while others single-handedly charged machine gun nests.

Military historians all agree that the infantry used a combination of incredible discipline and bravery to advance under heavy fire and in confusing, hectic conditions, even when their officers fell and were no longer able to issue commands.

It was a victory that came with a cost that will never be forgotten: 3,598 Canadians were killed and another 7,000 wounded.

In 1922, the French government gave Vimy Ridge and the land around it to Canada forever.