I realize now that, despite my age and the fact that I was a raw, new professional, Cofidis threw me in at the deep end. Yet I survived February and was due a couple of weeks off racing in March, during which I would train hard, in the hope of getting back on top of things.

After one six-hour day training in the mountains behind Nice, I came home to a message from Guimard. He wanted me to race in Tirreno–Adriatico, the tough and mountainous week-long stage race crossing the backbone of Italy, tracing a route from the Mediterranean coast to the Adriatic.

I told Guimard that I didn’t think it was a good idea, as I was tired from the recent big block of training. He didn’t listen. Off to Italy I went. So it was at Tirreno, before the race even began, that the scales definitively fell from my eyes.

—

In 1997, the UCI introduced what they called a “health check,” a new 50 percent limit on hematocrit, to guard against excessive use of artificial EPO, the red blood cell booster. Hematocrit is the percentage of oxygen-carrying red blood cells coursing through your veins. I’d heard talk of this but had no idea what it meant, what my hematocrit level was or ever had been. In fact, up to that point I don’t think I’d ever done a blood test. But I was learning fast, and it became clear that, during the EPO era, hematocrit levels were the cyclist’s holy grail.

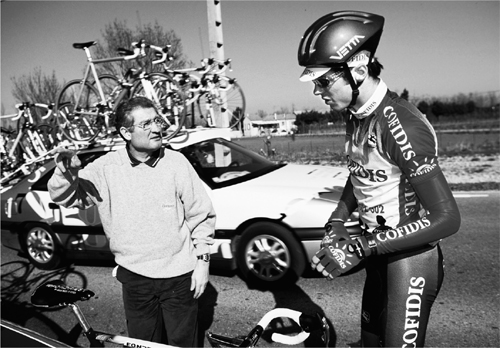

February 1997, in the south of France. The legend Cyrille Guimard and neo-pro moi.

EPO (erythropoietin), like cortisone, is naturally produced, making it very hard to find in anti-doping controls. Prior to the creation of an effective test, during the first ten years of its popularity it was impossible to detect. In essence, its benefits are the same as altitude training—some riders used to call it altitude training in a syringe.

By the mid-1990s, EPO use had become excessive, and there were plenty of stories in the peloton of those who’d pushed their hematocrit level to over 60 percent, and whose blood was like thick soup.

Heart failure had been widely linked to EPO abuse—there were stories, urban legends, of riders setting alarms to wake themselves through the night in order to do sit-ups, or some other exercise, as insurance against their hearts stopping.

The UCI knew that EPO use was rife, but was, apparently, powerless to stop it. The health checks weren’t dope tests, because if you tested “positive”—that is, were over the 50 percent threshold—you were simply suspended for two weeks. If, after that, your hematocrit, was back below 50 percent, you quietly resumed racing.

Of course, the presumption was guilt if you did get suspended, and in the majority of cases, rightfully so, but for a few it was an undeserved black mark. Some do have higher natural hematocrit, be this genetic or simply because of living or training at altitude. A small percentage of the professional peloton carried certificates demonstrating their high hematocrit, but these were not easy to get and required years of supporting data as proof. All in all, it was very basic science, yet the “health check” did serve to rein in the he-who-dares attitude toward EPO use.

We had a shitty journey to the start of Tirreno–Adriatico, arriving at Sorrento in the small hours after a late-night drive from Rome. We were billeted in a grand but faded old hotel that had seen its best days long ago. The first stage was an afternoon prologue time trial, but because I didn’t even have a time trial bike yet, I was using my training bike and wheels that I’d brought from Nice.

I was still unaware of the excesses of EPO, so when I went out for a ride the morning before the prologue, with a group of older pros, I was puzzled by why we were going so hard and so far, when I’d imagined that the ride would be a short “loosener” after the long journey. I was dropped on the first hill and turned around and went back to the hotel, decidedly worried about what awaited me in the race.

Later, I began to understand the thinking at the heart of that manic pre-race training ride. They were trying to ride the EPO out of their blood. Tirreno–Adriatico was likely to be the first race in which the UCI was going to use the new 50 percent test. There’s no doubt that a large number of the peloton were using EPO, but all to differing levels. So it was impossible to know how many were actually teetering close to the 50 percent limit.

One thing is for sure: none of them wanted to go over 50 percent. The word was that it was a good idea to keep training hard right up until the race started, in a bid to keep hematocrit low. I just thought they trained like that before every race and that it had been easy for them and hard for me. But it was a demoralizing start to a painful week, and I finished only 100th in the prologue.

I worked my arse off at Tirreno, looking after our team leader, Maurizio Fondriest. The stages were all fast and crazy, and we seemed to end on hilly finishing circuits every day. I don’t think I made it around one of those with the rest of the peloton.

One day sticks firmly in my mind. We had been lined out for over an hour, grappling to hang on to a fierce pace. I was doing everything I could just to hold the wheel in front of me and prevent myself from dropping back through the convoy of following team cars. But it was killing me. I was so tired that I was barely able to get out of the saddle after each corner or haul myself over the smallest inclines.

Just as I was about to give up the ghost, I looked up and saw Robbie McEwen, the Australian sprinter, swing out of the line of riders, waving his arm in the air, angrily shouting obscenities. Eventually, he looked behind him, by which point he was not so far ahead of me.

Robbie wasn’t done, though. He put his head down and started sprinting back up to speed alongside the line of riders, only to begin ranting again.

“FUCKING JUST STOP!” he screamed. “THIS IS NOT FUCKING BIKE RACING!”

I felt better after that. Later, when the pace eventually dropped, I introduced myself. It was the first time I ever spoke to Robbie, and he made me realize that I wasn’t the only one finding it hard. I’m grateful to him for that.

I also got introduced to “recovery”—or récup—methods at Tirreno. This was the use of injected vitamins to speed recovery from racing and keep your blood levels at a “healthy” level. I remember, after one stage, lying on the bed, watching my roommate Frankie Andreu opening syringes and breaking ampoules, in front of the TV.

Another rider came in the room, looked across at me, and said to Frankie: “Sure he should be seeing this? Wanna do it in my room?”

Frankie, in his very pragmatic way, simply replied: “He’s gonna see it sooner or later—it’s no problem.”

I got on pretty well with Frankie. Yes, he was grumpy, but you knew what you got with him. I asked him later on what he’d been doing.

“What was that you were injecting?” I said.

“Vitamins. Iron and vitamins. The usual, all legal, don’t worry.”

“Does it make a big difference?”

“Don’t know about big, but you know, David,” he said, “small things make a difference.”

I was pretty sure I was irritating him, and the bottom line was that I wasn’t about to start injecting myself, so what did I care? I tried to be as nonchalant as possible about it all. I was curious, though. What exactly was “the usual”? What did it do and where did he get it? And how the hell had he learned to inject himself?

As the race went on, I realized that most of the guys were doing “recovery.” They all had their own little medical bags with their ampoules and syringes, and it did not appear to be any different to them than having a protein drink or some amino acid capsules. Injecting yourself was normal.

—

There were other things that I had to get used to. Ice was regularly delivered to rooms, by the soigneurs, in little plastic bags. I’d noticed it a couple of times and thought nothing of it; after all, ice is a sportsman’s best friend.

I was picking up on it more and more but not noticing any correlating injuries. I couldn’t figure it out. When I was sharing with somebody who received one of these late-night or early-morning ice deliveries, he’d disappear into the bathroom soon afterward with another small bag, normally a shoe bag or large toiletry bag, dug out from his suitcase.

Incongruous visits to the bathroom by roommates was one more thing I was growing accustomed to. Most were unlike Frankie and hid everything from me. I would tell myself they were protecting me from knowing too much too young, but in honesty I think they were simply protecting themselves.

There was always an urge to dig around in their suitcase when they were away at massage or elsewhere, but at that stage, that would have been an unforgivable faux pas—a neo-pro, a jumped-up Brit, found rifling through an older pro’s suitcase?

I would have been a dead man walking if I’d been discovered. In that world, I was at the bottom of the food chain, a burden to the team, more than likely a dud who would not make it further than my first contract. I had no rights and few expectations.

I had to impress them and to prove myself. It wasn’t just my performances on the bike that were being judged. I had to make myself liked in order to ease my acceptance within the team and within the sport. This was especially true for a foreigner on a French team: France is perhaps the most chauvinistic of cycling nations.

After we got back to Nice, I managed to pluck up the courage to ask Bobby about the ice deliveries. He was straight with me, telling me what he’d seen: that some of the guys were using EPO, and that EPO has to be kept chilled or it’s ruined. So they kept the ampoules and syringes in an ice-filled thermos. Twice a day they’d replenish the ice.

If it wasn’t chilled, EPO didn’t work—and you’d come down with a fever that would leave you pretty damn sick for twenty-four hours. Then there was the pain of the wasted expense and the stress of sourcing more.

I didn’t ask Bobby much more than that. I’d learned that I could really expect to ask only one question; otherwise, it all became uncomfortable and reduced my likelihood of ever being able to ask any more questions on the subject.

Bobby was great, though. Like Frankie he was open with me and treated me with respect beyond my neo-pro status. He told me about how EPO use had become rife, especially in Italy. I did slide one last question in there, the same one I’d put to Frankie, the one that now interested me the most.

“Does it make that big a difference?” I asked.

“It can turn a donkey into a racehorse—from what I’ve seen,” he told me.

It’s hard to describe my feelings after he’d told me that. In a way I was relieved that there was something going on that explained the massive difference between the amateurs and the professionals. It meant that I wasn’t doing that badly; I was simply young, lacking experience—and clean.

But it also confirmed that there was some bad shit going on. It wasn’t the sort of thing I could just tell my mum or anybody else. My initial shock and sadness on discovering such a degree of doping already seemed a lifetime ago. What I was beginning to learn was too big for me to fully grasp, let alone comprehend. The “system” was already working on me.

I was wrecked for ten days after Tirreno, too exhausted to ride for more than an hour and a half. There was no way I could even contemplate racing. The team wasn’t bothered, though, and I was sent to Cholet–Pays de Loire, a one-day race in Brittany, three days after Tirreno finished. I can’t remember it; if I finished, then I’d be surprised.

I went back to Nice, skulked around, bought some Rollerblades, and started skating again in an attempt to remember happier times. That backfired when, after two years off the skates, I fell badly trying to slide along a rail, smashing my leg and giving myself deep tissue damage.

Obviously, I couldn’t tell anybody, certainly not the team, so I just kept quiet about it and hoped for the best. I visited my mum and Fran back at home and tried to ride my bike there, but it was a lost cause. I returned to Nice to an empty apartment, as Bobby was away racing.

Living in Nice wasn’t quite the existence I’d imagined. Although it was much better than northern France, life was becoming lonely. Instead of hanging out in the Cora supermarket in Saint-Quentin, we now had a panini stop down in Vieux Nice.

I started to read more and to listen to music, buying many books—Irvine Welsh, J. G. Ballard, Bret Easton Ellis, James Ellroy, and Cormac McCarthy became favorite authors—and numerous CDs. That was about the only thing I spent money on during that first year.

I also started to feel a little ashamed, aware that perhaps being a professional cyclist wasn’t something to be very proud of. I tried to develop myself by widening my interests, with music and reading at the heart of things. And reading helped while away the endless hours of nothingness I had to fill.

I realized I was going to need somebody who could be my mentor through these early years. So I contacted Tony Rominger, the elder statesman of the team, as he seemed to be one of the more cerebral—and hugely successful—cyclists out there. Tony lived in nearby Monaco, which made contact a lot easier. I thought if anybody would be able to steer me through all the shit, it would be somebody like him, somebody nearing the end of his career and who had seen it all.

Tony seemed almost flattered when I asked him if he could help me out. He was very keen, and I flew to Manchester to see him as he was undergoing some tests for an hour-record attempt in the new velodrome.

It was the first time I’d ever been to Manchester. The velodrome was quiet back then, in the pre-Brailsford-run Team GB days, and barely used. There wasn’t the hustle and bustle of a hugely successful national squad buzzing about as there would be in years to come.

Tony was there with a small entourage. When I arrived, he was whirling around testing equipment and positions, so I left them to it and found myself a basketball and started shooting hoops on one of the courts in the center of the velodrome.

Eventually, as they began wrapping up, I wandered over. Tony was, as ever, excited and happy. He introduced me to the small group, one with his head down over a computer. Tony pointed in his direction and said: “That’s Michele, he’ll join us for lunch.” Immediately, I realized that this was Dr. Michele Ferrari, a legend in the professional peloton.

In European cycling, Michele Ferrari had become the guru of sports doctors. He was already a controversial figure even before the allegations and scandals that would surround him in the years to come (he was convicted of doping offenses but later acquitted following an appeal). At this time, though, his was still a name riders were proud to be associated with. He coached only the best and had been a student of Professor Francesco Conconi, perhaps the first recognized sports doctor in cycling.

I had heard of Conconi as a junior, as any physiological testing I did was based on the Conconi Test. This was a ramp test that measured the point of maximal steady state workload, that is, the highest intensity effort an athlete could maintain for a prolonged period of time—in other words, his threshold.

After Ferrari had finished poring over Tony’s results, we all went back to the hotel where they were staying. Tony suggested I get a massage from his personal soigneur. Massage was one of the things I disliked most about being a professional, as I could never relax, and whoever was massaging me would have to keep reminding me to decontract my muscles. It just didn’t come naturally to me, but I thought it would be bad form to ignore what Tony said, so I took his advice.

Afterward, I sat down for lunch with Michele and Tony. I’d never thought about Ferrari having anything to do with my relationship with Tony, and thankfully, neither had Tony. But Michele was still curious about me. He asked me about my statistics—weight, height, threshold, and power—I was simply a set of numbers to him. At one point, out of the blue, he reached across the table and pinched my biceps. I wondered what the hell he was doing.

“Not bad,” he said. “Could get skinnier though.”

Ferrari was obsessed by weight. In his world, the lighter you were, the faster you would be. I didn’t really understand his philosophy—if I’d got any skinnier I wouldn’t have been able to ride my bike, let alone race it.

He was an odd fish, something of a nerd. For a man with the reputation he had, he was hardly imposing. He had an odd rodent-like appearance, accentuated by a skeletal physique and slightly protruding teeth. He topped his look off at the time with some oversized, slightly feminine, spectacles.

What he lacked in physical presence, he made up for in seriousness. Cycling wasn’t romantic in Ferrari’s eyes, it was simply about numbers: weight, watts—and wads of cash. It was all business to him. I saw that within minutes of this, our one and only meeting.

Over the weeks that followed, Tony took me under his wing. It was Tony who told me the harsh realities of professional cycling in the 1990s.

We were out on a training ride together, just the two of us, an easy ride—and there are very few to be found between Nice and Monaco—of some laps around Cap Ferrat. It was a remarkably beautiful place to learn such ugly truths.

By this point, I understood that most of the top guys were using EPO, and that even those who weren’t knew about its potential, but I still couldn’t believe that that was the only way to win big races. That didn’t seem right and surely wasn’t possible. How could it be so prevalent? Did no one care?

“Tony,” I began, “is it possible to win big races without EPO?”

At first, he was a little taken aback. “Oh. Uh, well, it’s possible,” he said.

“In one-day races, sure, I believe it’s still possible. The Classics, if you do everything right, yeah, it’s possible. I’m sure of that.”

“What about the Tour de France?” I asked.

“Hmmm.” He thought for a moment. “No, it’s not possible. Over three weeks you can’t compete against guys on EPO.”

“Really?” I was devastated. “Shit. Why?”

“EPO allows you to go faster for longer. I mean, you still have to train and diet and do everything else, but with more oxygen you can stay at threshold for longer and recover faster. That’s what the Tour is all about.

“It’s just the way the sport has gone,” he said. “It’s sad. When I started, we used to turn up to Paris–Nice with two thousand kilometers in our legs. Well, maybe!” That triggered the classic Tony chuckle.

He continued. “Now some guys are arriving with eight thousand or more kilometers with full preparation. My God, we used to race with leg warmers those first races. Now they are treating it like the Tour de France! EPO changed everything. Now everybody thinks they’re champions. I’m glad my career is at its end now—the sport’s not the way it used to be.”

Well, great—fucking brilliant, I thought. Now I knew.

Strangely, what he said didn’t really have that much effect on me. I’d figured out for myself what was going on, but I just wanted to hear it confirmed from somebody who would know.

What Tony told me meant that I didn’t need to question it anymore. Those were the facts, I told myself. Get used to it.

—

Preparation was a term I was to hear more and more. It had another more sinister meaning. If you were prepared, it meant you were doped; it also meant you were ready.

“Il est bien préparé,” they’d say. If that was said about a team leader at a race; it meant that it was all systems go and that his team would be working their arses off for him.

It is hard to explain how I felt about this, and it may also be difficult for some to understand. I had been upset and angry when I’d been confronted with the realities of pro racing at my first race. But Mum had been right. I could just walk away, pack it all in, go back to Britain, and become an art student.

But I didn’t want to do that: I loved racing, and I loved my dream of one day racing in the Tour de France. I was young and blindly optimistic. I still had a lot to learn, about the characteristics of the races, the intricacies of the peloton, which wheels to follow and when. I reckoned I had a good few years before I would even reach my physical maturity, and who could tell what I’d be able to do when I was at my peak—so I left it at that.

Doping was not for me; what the other guys did, well, that was nothing to do with me. If the riders, governing bodies, teams, race organizers, and media weren’t doing anything about it, then what the hell could I, a twenty-year-old neo-pro from Scotland, do about it?

And that was that. I had to live with it going on all around me.

David Moncoutie, a young Frenchman who joined Cofidis when I did, was of the same opinion. We did our thing and kept our heads down. It was amazing how well that tactic worked. The need to dope wasn’t foisted on us because in many ways the idea was to see how far we could progress à l’eau claire, on simply bread and water. That would gauge what sort of talent we had and hint at what sort of future lay in front of us. So both of us just trained hard and turned up at races where we would systematically get our heads kicked in. And race we did: I had over eighty days of racing in that first year as a pro.

I had to quit most stage races due to exhaustion, climbing into the voiture balai—the broom wagon (so called because it brushes up the weak and sick who can no longer ride their bikes to the finish)—on the last day. Yet I don’t think there was one race where I wasn’t in a breakaway on one stage or another. I could always get in a break if I wanted to, but I wasn’t really strong enough to survive in it, and, come the finale, I was too tired actually to race for the win. The next day, still tired from the effort, I would be on my hands and knees and could barely finish the stage.

I didn’t confront my first “recovery” moment until a few months into the year. It was at the Vuelta a Asturias, a five-day stage race in northwest Spain. It was my first race in Spain, and it was very different from racing in France or Italy.

In France, there was no rhyme or reason to the racing. Sometimes, it was almost amateurish the way in which everybody just smashed themselves from kilometer zero to the finish line.

The Italian scene, on the other hand, was pure finale racing. The days followed a predictable scenario; start fast, get faster, finish at warp speed. I never really experienced warp speed, as I was generally out of the picture before then.

In Spain, there was a very civilized feel to it all: a calm to the racing. There was little other than stage racing on the calendar, and these followed an unchanging pattern. Flat stages finished in mass sprints won by sprinters, although a kamikaze breakaway would slip away early on, and usually be controlled by the chasing peloton until the final 10 kilometers.

Summit finishes were won by climbers, their teammates controlling the day’s racing until the bottom of the decisive climb. If there was a time trial, then the team with a general classification rider strong enough against the clock would control the race, and the outcome would be decided in the time trial. Each day, when we rolled away from the start, we knew what awaited us. It was refreshing and more akin to what I had expected of professional racing.

But the shock came when we hit the mountains. The climbing speeds were like nothing I had encountered in France or Italy. The Spanish are primarily great climbers, and this stems as much from nurture as nature, as most racing in Spain, from junior level up, is hilly.

In order to be a successful pro in Spain, you have to climb fast, in much the same way as in Belgium all racing is flat, windy, and cobbled, breeding hard northern classic riders. The Italian scene breeds a combination of the two, as the majority of their racing is hard, tactical one-day racing.

I was considered something of a climber with the amateurs, and my time-trialing ability meant that I was expected to be a general classification rider in the future. In theory, Spanish racing was made for me. But in Spain, the climbing stages were ridiculously fast, and once again my weakness riding out of the saddle was exposed, as my arms gave way before my legs. I was out of my depth, a minnow in a sea of big fish.

Tony Rominger was using that Vuelta a Asturias to lose weight and fine-tune his condition for the Tour de France. His soigneur, Torron, was on making-sure-Tony-had-no-chocolate duty and also focused on ensuring that his pre-race morning meal was pasta with olive oil, nothing else.

Tony was a clever man; he spoke six languages fluently and was very dynamic, but when in the team environment, he was cared for like a little boy. His big thing at this time was PlayStation football, which he loved and took very seriously.

Meanwhile, I was expected to room with a young French pro who wasn’t a renowned talent or even a key member of the team, but seemed to have been in the right place at the right time to fill the quota of French professionals required on ours, a French team.

When we’d all met at the gate for our flight to Spain, everyone was relaxed and jovial except the young French rider, who kept to himself and looked a little on edge. Once he started talking, we couldn’t stop his bragging about how hard he’d been training. On the flight I sat with Laurent Desbiens, who was in his first year back racing after a doping ban. He and Philippe Gaumont, also in Cofidis, had served a ban together after testing positive while on the same team the year before.

Both Laurent and I had registered that there was something up with my future roommate.

“I can see it in his eyes,” Desbiens said, as we chatted on the plane.

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“He’s allumé,” he replied. “Lit up …”

When we got to Spain, it became clear that “lit up” was an understatement. The young Frenchman didn’t speak to anybody on the way to the hotel, only glancing at Desbiens nervously as we sat on the bus.

I wasn’t overjoyed when I got to the hotel and saw that the two of us were sharing, but there wasn’t anything I could do about it. I dropped my stuff, ate, and had a massage. When I came back from massage, my roommate wasn’t there. About half an hour later, one of the soigneurs came in and asked angrily what I’d been saying about him because he’d apparently complained about my saying things to the others. I was completely taken aback, annoyed even, and roped in Desbiens to back me up. By this point, my roommate was avoiding me, and when he didn’t turn up at dinner, we were starting to get a little worried.

When I got back to the room, he had locked me out. Eventually, thanks to a spare key, we got in.

He was in there, looking completely deranged. He started whispering, saying that the room had been bugged with microphones and telling us that we were being listened to. The soigneur didn’t hesitate; he immediately told me to pack up my stuff, as I’d be sleeping in another room.

Desbiens wasn’t at all surprised to learn that the kid was amphetamined up to his eyeballs. He’d obviously taken it to panic train before the race and had ended up “cooking” his brain, a condition otherwise known as speed psychosis.

This, it turned out, was standard practice. Pot Belge, a concoction of drugs, was used to underpin big training sessions, and there was certainly a type of pro who loved the allumé training session. They used to say that if you were allumé, it didn’t matter if it was raining, as there’d be sunshine in your head.

That was perhaps not a bad thing for those tackling their early season six-, even seven-hour rides in the cold and wet. Often, however, they didn’t even really need to light up—it was seen as just good fun. Taken in the wrong doses or abused—yes, even amphetamine users can be responsible—you could not only destroy your body but also your brain, just like my friend. That was the last we were to see of him.

His plight demonstrated the risks riders ran if they “experimented” on their own. It was usually the soigneurs who dealt with rider medication. Any self-respecting soigneur would have his own comprehensive medical bag and, if the doctor was not at the race, which was often the case, then the soigneurs would assume the role—often with relish. The team truck would also have a sort of mini-pharmacy, nothing illegal, just a comprehensive array of pharmaceutical supplies.

The big fad at the time was for Italian “recovery” products. This was what I’d seen Frankie injecting. Prefolic acid, Epargriseovit, and Ferlixit: prefolic acid, vitamin B, and iron. These were all supposed to help keep your blood healthy and to maintain your oxygen-carrying capacity at its highest. Up to this point, it was all I had seen.

It was common knowledge that I didn’t do “recovery,” and I think it was beginning to annoy some of the staff in the team, especially the soigneurs. They could see that I was a talented racer, but they also knew what I was competing against. I think they thought I didn’t understand, that I was naive, perhaps stubbornly idealistic, that I hadn’t grasped I was now a professional in a world in which where there was no room for idealism.

My soigneur took it upon himself to explain, as he had done previously, that there was nothing “wrong” with “recovery.” It was not illegal and, far from doping, it was a simple injection that gave my body the vitamins it couldn’t replace through eating alone.

I’d spoken to Tony about it during the week, and he’d said that the combination of prefolic, Epargriseovit, and small doses of Ferlixit could actually boost your blood values by a point, completely naturally.

I thought about it some more. Maybe they were right; maybe I was just being stubborn. After all, this wasn’t doping. If I was going to take a stance against doping, then I needed to make sure I did everything else within the rules that might help my racing.

So when my massage was over at the penultimate stage in Asturias, and my soigneur asked if I was sure I didn’t want to do recovery, I finally said:

“Bon, allez, je vais le faire.” Okay, fine, let’s do it.

I sat on the massage table and watched as he got out the ampoules and the paraphernalia required to inject it intravenously. Everything was new and disposable, the syringes and needles were all individually wrapped in plastic, and he carefully opened all of these. There was one bigger syringe and one smaller, one needle and a butterfly: such a lovely name for such an ugly tool.

The butterfly was the little plastic-winged needle at the end of a thin tube, used to make the IV junction between the vein and the syringe. The prefolic was in two ampoules. One was like a mini-jar with powder in it, the other was a little standard ampoule with clear liquid; this liquid needed to be siphoned out and mixed into the powder. This was then shaken and left.

He broke the top off the pinky-red Epargriseovit ampoule and drew that out into the bigger syringe, then the dissolved prefolic mixture could be siphoned out into the same syringe. This was put to one side, while he snapped off the top of the Ferlixit ampoule, a very dark brown liquid and exactly what one would expect iron to look like. He drew half of the ampoule’s contents into the smaller syringe and laid it carefully down next to the other syringe.

It was strange watching all this, taking it all in. Once the two syringes were lying there, side by side, it was hard not to question what I was doing. I felt uncomfortable, but I was now too embarrassed to say, “No—stop.”

So I sat there as he put a tourniquet on my arm and told me to clench my fist; my veins bulging out like the roots of a tree. He joked about how hard it was to find a vein. I smiled, trying to find it funny.

The butterfly was now brought out and he wiped down the vein he’d chosen in the crease of my arm. I didn’t like needles. I’d been avoiding my tetanus booster for years, as I hated the idea of being stabbed with a needle. And now this …

And then it was in.

The butterfly gently pierced the skin and the wall of the vein and laid its wings down upon my arm. A couple of centimeters of blood pumped up through the tube before stopping, the pressure of the tourniquet limiting blood flow. He then connected the bigger syringe to the end of the tube and deftly removed the tourniquet. With one hand holding the barrel and the other gently pulling back on the pump, my blood flowed smoothly up and entered the syringe with a tiny little exploding cloud.

“Ça va?” he asked me.

I answered, “Oui.”

And slowly, he began to empty the syringe into my body.

He told me that I should tell him if I felt it burning. He emptied the syringe completely and pushed air through the tube till there was just a drop of liquid at the tube’s end, near the butterfly wings. Then he smoothly disconnected the empty syringe and reconnected the smaller darker one. This was the iron, and he said he had to pump this through much more slowly.

“Pourquoi?” I asked.

“Because that’s what you have to do with iron,” I was told.

Once again, my blood was sucked back up through the tube till it met with the barrel of the syringe, only this time there was no pretty little exploding cloud, as the iron was darker than the blood.

We sat there in silence apart from the occasional “Ça va” as the syringe was emptied.

And that was that. A line had been crossed. I now did “recovery.” I didn’t like doing it and would do it only after the hardest days in stage races. I was a light user for no other reason than I didn’t like injections.

My season progressed. I began to adapt to the racing and finally to get some results. I was close to the top ten in time trials, began finishing stage races, and, unlike most other neo-pros, actually made it into breakaways.

These were all big achievements for me that first year. I had high hopes of success in the Tour de l’Avenir—literally translated as the Tour of the Future, a mini–Tour de France, organized by the Tour de France promoter, ASO.

There was a prologue and a time trial before it headed off into the mountains, and I’d fixed my sights on winning both. The prologue I won with relative ease, but in the time trial, I was swept aside by French rider Erwann Mentheour.

I finished the race and was being congratulated by everybody on what seemed an inevitable victory when Erwann came ripping through the finish taking my “fastest time” and pummeling it.

It was my first experience of having a win taken from me by a guy who was clearly doping, something he subsequently admitted to. But to his credit, Erwann didn’t really hide it and effectively apologized to me the next day. That didn’t stop me from quitting the race and going home, though.

I ended the season racing for Great Britain in the World Championships in San Sebastian. I was excited at the prospect of being able to spend some time with the British team, which felt like a safe, friendly place compared to where I had spent most of the rest of the year.

I didn’t know at the time that Tom Simpson had won the world title in San Sebastian thirty-two years earlier. But then, when I was twenty years old, I didn’t really know much about Simpson’s story.

Robert Millar was team manager that week, and we got on well. Chris Boardman and I were the two riders entered for the time trial. Chris took bronze in the trial, and I ended up in the middle of the field, but struggled in the road race and didn’t finish. One of the key moments of that week in the Basque Country was meeting Harry Gibbings, a charismatic Irishman who was working for Oakley Sunglasses at the time.

Harry and I hit it off straightaway and my first pro season ended with our partying the night away together, post-road race on Sunday evening. At some point I dropped my phone in the harbor, Bjarne Riis took a cigar out of my mouth and stuck it down my shirt, we both lost our jackets and went bodysurfing in the freezing sea. I woke up the next morning 30 kilometers away in Harry’s hotel, fully clothed apart from one bare foot. It was to set a precedent for our times spent together over the next eight years.