No human authority can encroach upon the power of an investigating judge; nothing can stop him; no one can control him.

Honoré de Balzac

My first meeting with the Paris-based judge in charge of the Cofidis affair, Richard Pallain, was on July 20, 2004. Judge Pallain was a fit, health-conscious middle-aged man, who nibbled on big bars of chocolate, while massaging a stress ball.

I had expected robes and wigs, figurines and paneled rooms, yet the courthouses in Nanterre were far from grand. The building housing Judge Pallain was a gray, soulless, shabby tower block. It didn’t make me feel like I was being reprimanded by the grandeur of La République Française, defenders of égalité, fraternité, liberté. Instead, I felt more like I was being hauled in to pay overdue council tax or cough up for a speeding fine in a local préfecture.

Nonetheless, I was terrified, and my first meeting with Judge Pallain was a horrible experience. I was scared and physically very nervous. I wasn’t in my Biarritz bubble anymore, where a round of drinks and a group of friends prevented me from facing up to the bitter truth.

I was grateful that my lawyer was Batonnier Paul-Albert Iweins, one of the most respected lawyers in France, with a depth of experience and knowledge of life and the law that I could not even begin to fathom. We hit it off almost immediately.

To walk into the courthouse at Nanterre with Paul-Albert was an honor and a privilege. His serenity and skill helped me enormously during the two years of the investigation. He bubbled with an intellect and curiosity that was matched only by the love he had for the law.

July 2004, Nanterre. Paul-Albert Iweins and I on one of our numerous visits to the courts.

Appreciating the long hours Paul-Albert worked, the time he spent traveling, his juggling of personal and professional, was an eye-opener for me. This wasn’t for a finite period of his life, as it might be for an athlete, but for the majority of his working life. I realized how immature I had been ever to have thought I had it harder than other people. It was another reminder of how little I knew about the world.

The first few times we were called to meet Pallain in Nanterre, a handful of photographers, TV crews, and journalists turned up. Paul-Albert gave them an appeasing statement while I waited, out of reach, on the other side of the security checks. At that time, there wasn’t really anything to say, other than: “I am sorry.”

Once inside, Paul-Albert told me to spend as much time as possible in the lawyers’ private waiting area. This was not normally open to clients, but because of Paul-Albert’s standing I was allowed in there. I am sure he knew this would give me confidence and empower me before facing the judge. The only other option was to wait in the corridor outside the numerous Juges d’Instructions offices.

I did spend some time out there, watching as, one by one, hollow-eyed, broken men drifted in and out of the judges’ offices. Paul-Albert had explained to me that many of those being investigated by the judges were successful, powerful members of French society.

Some of them were in a terrible state as they sat waiting to meet their “inquisitor.” Once an investigation had got to the point where a meeting with a judge was deemed essential, then the fall from grace was inevitable.

At the first confrontation with Judge Pallain, we went through statements from the forty-eight hours I’d spent in police custody in Biarritz. He asked me to respond to any statements or incriminating evidence before deciding whether I was to be a witness or defendant.

It was clear, almost immediately, that I was going to be a defendant, although that hadn’t stopped me from believing that, maybe, I just might walk out of his office as a mere witness, free of charges. But the first face-to-face meeting with the judge removed any doubt over that.

In all, the meeting lasted about five hours—five hours during which he sat and listened attentively as I explained my conversion from idealist to doper. Justifying my mistakes wasn’t possible, but I could describe what had happened and try to explain the process that had led me to sit in his dismal office a disgraced man.

Paul-Albert had warned me that I needed to listen to every word and query anything that I wasn’t sure about. He also warned me that the judge would manipulate and twist the words of others, but that I was not to be perturbed by this. Instead, I should ask to read the statement of any other witness or defendant he quoted.

Over time, the meetings with Pallain became increasingly surreal. His offices were overheated and shabby, his secretary flirtatious. I was disgraced, exiled from my sport, yet instead of reproaching me, Pallain—the judge seeking to establish my guilt over doping—revealed his credentials as a cyclist by asking me for training tips.

As we met with him more often, he would ask me more detailed questions, about fitness and equipment, even at one remarkable moment comparing Vo2 max levels with me. The judge investigating the Cofidis doping scandal was a “bike perv”—I couldn’t believe it was happening.

Time went on, but the case moved painfully slowly. I would receive a convocation from Judge Pallain, citing the date and time that I was to be at his office. There was never an agenda, and I would only find out why he wanted to see me shortly before the meeting.

Would it be to go over my statements, or those of others? Would it be a query over phone transcripts? Maybe it would be a confrontation with one of the other Cofidis affair culprits. Or maybe he just wanted some training tips. I would block it out of my mind until Paul-Albert could worm it out of the judge.

The meetings in Nanterre soon established a routine. The night before, I would stay at Harry’s place, near the Arc de Triomphe. I’d leave the apartment around 7:30 a.m. and set off on foot down the Champs-Élysées toward Paul-Albert’s office on Avenue Montaigne.

I would meet Paul-Albert’s protégé, Julien, at a little café within spitting distance of their offices, which were above the Chanel store. It was all very Parisian, and, like most Parisians, we would start the day with a coffee and croissant.

The café owner and I would often chat about cycling before Julien and I headed off to Paul-Albert’s offices to go over statements and discuss the day ahead. Then we’d drive across the city to Nanterre to meet the judge.

Naturally, this being France, we broke for lunch, heading for a little café-restaurant in the building opposite the courthouse, filled with lawyers bolting down a prix fixe menu. As the meetings with Pallain came and went, lunch there became a habit and was soon the highlight of every visit to Nanterre.

By the time we’d walked over to the restaurant, Paul-Albert would have said all he wanted to say about the case, so we would chat as if we were simply old friends who’d chosen to have lunch together. We would have a glass or two of wine, I would tell him about bicycle racing, and he would tell me about the law. They were some of the best lunches I’ve ever had, a glimmer of normality in those dark days.

After lunch, we would head back across the road to the hothouse that was Pallain’s offices and resume where we’d left off. The statements would be scrutinized and any revisions made. I could imagine how easy it would be to be railroaded into saying something incriminating simply through the judge’s chosen wording. But we stuck at it and made endless corrections. At the conclusion of each statement, it would be printed out, we would read it, and, if agreed, I would then sign it.

Each statement, printed and signed, was another weight off my shoulders, another little exorcism. It was a painful process, but each piece of paper, detailing my downfall, lightened my mood a little more.

When we finally left Pallain after that first session, I was exhausted. My testimony was clearly going to be an important element in the court proceedings, but by then, I didn’t care what he charged me with. I was shattered. I just wanted to get as far away from Nanterre as possible.

—

After we’d left Nanterre following that first meeting, Paul-Albert drove me back through the rush hour into central Paris. Maybe it was his sense of humor, but he dropped me off outside the Café Drugstore, by the Arc de Triomphe. We shook hands and I got out of the car, turning to look back down the Champs-Élysées and beyond, toward the Place de la Concorde.

I stood and stared, remembering when I had raced in the final stage of the Tour de France, and the moment when, after the steady climb toward the Arc, the peloton slows to a near standstill, then turns before haring downhill toward the fountains and the Concorde once more.

I knew from riding slowly through that tight turn that it was possible to see into the eyes of the fans behind the barriers. Now I stood at that spot, as distant from the Tour as anybody. I had built my own barriers, and they were bigger and stronger than anything the Tour de France would ever put at the side of the road.

I turned and went into the café. I bought a packet of cigarettes, sat down at a table, and ordered a dry martini. After a little while, Harry turned up. He stared at me across the tables, then strode over and promptly snatched the cigarette out my mouth.

“What are you smoking for?” he snapped. “You look fucking ridiculous.”

“Harry,” I said. “If I can’t smoke now, then when can I?”

He shrugged and sat down.

I told him about my day, from the broken men in the corridors of the courthouse to the pleasures of our simple lunch, from the wonders of Paul-Albert’s legal expertise to the weirdness of Judge Pallain. He let me sit, drinking my dry martini, smoking my cigarette, and recounting my woes.

Afterward, we headed back to his apartment. Harry had asked a couple of people over, as he thought it was best to keep my mind off it all. When we got to his place, they were already there waiting. I couldn’t switch moods, though.

I told Harry I needed a couple of minutes and wandered outside. There was a twilight sky above, but in the courtyard I felt more hemmed in, more overwhelmed, than ever. Most of the time, I coped with what was happening, but I would have moments when I couldn’t keep the darkness inside. So I would let go and allow it to flow out of me, and I would be left sitting there, surveying the world I’d destroyed.

After a while, Harry came out to look for me. He saw me and immediately gave me a hug.

“I need to go for a walk,” I told him.

Paris is a wonderful city to walk around. I found myself wandering through a beguilingly peaceful sixteenth arrondissement as the curtain fell on a beautiful summer’s day. My black mood slowly dissipated with each step, and I realized that perhaps there would be life after all of this, and that it could be a good life, one worth living.

Eventually, I found myself on rue Freycinet. I remember the street name well, because Freycinet was also my ex-girlfriend Katherine’s name. Farther along the street, there was a beautiful flower shop. They were closing up for the day, but I wandered in, taking in the colors and the beauty.

And then, standing in that flower shop on rue Freycinet, I knew.

I knew I would be okay.

It was going to be hard and I’d still have moments where I’d wobble, yet lost among those flowers, with my senses filling up, wrung out and exhausted though I was, I knew I’d be okay.

Paul-Albert had warned me that the judicial investigation could go on for years. Meanwhile, the fiscal investigation into my tax affairs was rumbling on. Now it was up to my accountants to fight my case and limit the damage as far as was possible.

It was becoming apparent that the French tax authorities were unwavering when it came to retrieving funds that they considered to be theirs. They were draconian when dealing with those who didn’t pay their tax in full, and it was all a bit of a shock to the London firm that had taken charge of my file.

Also looming on the horizon was my disciplinary hearing with British Cycling, which would decide the length of my ban. The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) code supplies a guideline for the length of ban for doping offenders, but ultimately, it is at the discretion of the rider’s national federation.

Until then, due to the leniency of some federations, no big-name rider had ever received more than a one-year ban. The hearing was scheduled to take place only ten days before Team GB competed in the Athens Olympics, and it was believed this would affect the judgment. Some people wanted them to make an example of me, and I had steeled myself for a four-year ban.

I was only twenty-seven, but at the time I believed my sporting career was over. I had no hope of coming back to cycling, but I knew that I had to go through the process and explain myself as best as I could, for closure, if nothing else.

Compared to the ordeals I’d endured with the French police and Judge Pallain, the hearing in Manchester was surprisingly relaxed. This was a friendlier environment. It also helped that proceedings were held in English.

It was strange sitting in front of the panel and pouring my heart out. They knew me, they knew my story—and they loved cycling. They weren’t intent on “getting” me, or tainting the sport; they were as pained as I was by what had happened. But at the same time, I could see how difficult it was for them to accept how I’d cheated and lied.

But I told them everything, and I was able to share my true sentiments about cycling and my team without it being used as ammunition by a judge. I talked of the doping “system” and explained the head-in-the-sand policy employed by most teams. I hoped they would understand.

Convinced that I would be banned for four years, I waited outside. It didn’t take very long before I was asked back in to the hearing.

The panel banned me from competition for two years. It was clear they were shocked by what I told them and understood that there were mitigating circumstances. For professional cycling, it was a landmark decision. Finally, a national federation had suspended a “hitter,” according to the WADA code. But having been convicted of doping, I now also had to deal with the pain of a lifetime ban from the British Olympic Association.

When I got back to Biarritz, I couldn’t bear to watch the Olympics—apart from one event: the Madison race in the velodrome. That was only because Stuey had told me he was going to win it. He had called my sister in tears when he’d found out that I’d been arrested. Two weeks after that, when he won a stage at the Tour, he didn’t hesitate to dedicate it to me, although he knew how controversial it would be to do so. But he’s that sort of friend. So when we’d spoken on the phone and he’d told me to watch the Madison, I was forced to confront my absence from the Games.

I got everybody together, and we all went down to Alain and Valerie’s place on the Côte des Basques. We took over the TV area, turning off the music and cranking up the commentary.

Stuey was as good as his word. A born track rider, he killed it, taking the gold medal emphatically, even though he hadn’t been on a track for eight years. He made the rest of the field look like junior racers, but emotionally, his triumph was too much for me.

I thought I’d be able to keep the lid on everything, but the realization that I’d never return to the Olympic Games swept over me, and, in front of everybody, I broke down. Until then, I’d never shown any of my sadness to my Biarritz friends. Now I sat in a busy seaside bar on a summer afternoon, my head in my hands, crying like a baby.

—

I knew I had to leave Biarritz. It held too many memories, many good but some bad, from the previous seven years. It was a hard decision to make, but I knew that I wouldn’t be able to start afresh as long as I still lived there.

The French were coming down hard on me, and it became obvious I would be much better off back in the UK, sheltered by British laws. I had always sworn I’d never return to live permanently in Britain, yet now it was my port in the storm, and I was thankful to have it.

The sporting world usually discards athletes when they are banned for doping. There is no process for helping, or learning from, a sanctioned athlete, whether it’s a vulnerable sixteen-year-old who has been duped by his coach, or a thirty-four-year-old multimillionaire superstar who has a highly paid medical team. They are all treated the same. Yet Dave Brailsford was already planning my rehabilitation and had talked of me living near Manchester.

So I was lucky to have Dave. He had made it clear to me that, before anything else, he was my friend and he believed that I should be rehabilitated. Steve Peters supported this view.

The irony was that, in many ways, Dave and British Cycling had already rehabilitated me, prior to my arrest. Thanks to their vision, professionalism, and working methods I had stopped both injectable récup and doping. Now that Dave knew the full story, he believed even more strongly that I deserved a second chance.

Meanwhile, I was running out of money. It was too expensive for me to pay a removal company to help me get back to Britain, so I decided that I would have to do it myself.

Thankfully, James Pope had offered to help—God knows why—but then only James would think a road trip involving the packing up of a convicted drug cheat’s apartment would be a fun way to spend your time.

So I rented a truck in London, I picked James up, and we headed off down to Plymouth to catch the ferry to Santander. We were on a tight budget, and the truck was pitifully underpowered. It struggled to go at a decent lick even when empty. Fortunately, that wasn’t a major worry, as our plan ensured that the ferry would tackle most of the return journey for us.

Back in Biarritz, we got straight to work, loading up the beautiful, lovingly chosen furniture that was still boxed up and standing around in the empty and unfinished dream house. Then we spent the rest of the day clearing out my apartment, as James demonstrated his miraculous packing skills.

I had decided that if I was leaving Biarritz then I was going to leave in style, with a party. We had designed somber black invitations reading, Dopage Dommage—Doping Damage. I wanted it to be a celebration with a hint of mourning. I invited everybody I knew—even the taxi drivers.

One of them, Philippe, an old guy with a limp, had always taken care of me, picking me up from airports after races and scraping me off the street in the early hours of the morning. He was my main man for getting around.

Philippe was the head cabbie and, perhaps because of his limp, a grumpy bastard. Everybody was scared of him, so it was even more special that we got on so well. We had become very attached to each other, and I think he took it the hardest that I was leaving.

When I told him that I was going to have a party to celebrate my time in Biarritz, he refused to accept that I was leaving and said he would not be coming to the party. Nobody expected him to show up, particularly as I don’t think he’d ever been seen farther than 5 meters from his car.

So when he was one of the first to turn up, dressed in black, it made my night. We sat at the bar and chatted—he made me promise that I’d come back, I told him that, yes, I would—yet we both knew I wouldn’t. I knew that things would never be the same again. Everybody stayed late, until the end, and the final farewells. For all the loneliness and mistakes, it had been an amazing few years, and I had grown to truly love my Biarritz.

James and I had given ourselves one more night in the apartment, to ready ourselves for the drudgery of the return journey. As the rain poured down that evening, I joked that Biarritz was crying because I was leaving.

Perhaps because of the turmoil, or because I’d become increasingly nocturnal, I couldn’t sleep. I’d left my longboard out, intending it to be squeezed into the truck at the last. I pulled my clothes on and decided to go out for one last skate.

It was the dead of night, about four in the morning, and as quiet as the winter nights when I’d often had the town to myself. I sat outside the unfinished house that I’d never spend a night in, then rolled down to the corniche of the Côte des Basques, so beautiful in the darkness and the rain, the way only Biarritz can be. I skated all the way down the corniche, memorizing every moment. It felt so peaceful.

Finally, I wandered through town and back up to the apartment, remembering all the good times and promising myself that I wouldn’t forget them. It was the good-bye I’d never given Hong Kong.

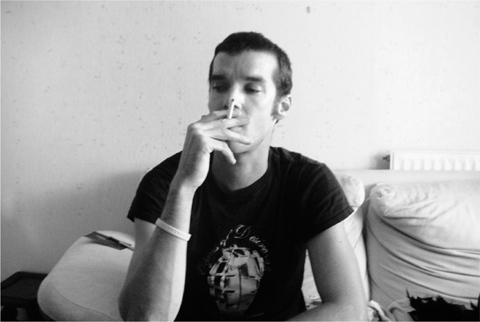

The morning after the night before. Matty Wilson captures me in all my washed-up glory, Livestrong band and cigarette making the perfect juxtaposition.

—

James and I set off early the next morning. It was only about 300 kilometers to Santander, but the route was tortuous, with barely any flat road. The truck was so overloaded that we would slow to an agonizing 60 kilometers per hour as soon as we climbed uphill.

Massive lorries would grind their gears angrily behind us, then overtake, horns blaring. It was painful going. Eventually, we got to Santander, but as soon as we were in sight of the port we knew something wasn’t right. There were no cars lined up waiting, and more worryingly, no sign of a ship.

I started to feel anxious. “Check the tickets, James,” I said. “It was today, right? Midday?”

James fumbled in his manbag. “Yep, all looks good.” Then he scanned the horizon. “So where the fuck is the boat …?”

“Oh shit,” I said. “This isn’t good.”

There were storms in Plymouth, and the crossing had been canceled. We’d have to wait for the next scheduled arrival. It was Thursday and the next sailing would be Monday. James was panicking. The chaos of my life had started to get to him.

“Dave—I’ve got to get home; we’ve got to get out of here. Seriously, this is too much.”

We had a snack. Over pizza, I faced up to the challenge that lay ahead of us.

“Well, there’s no way we can go back to Biarritz,” I said. “Not after all the farewells.”

James agreed. “So what do we do?”

“Drive,” I said. “Head up to northern France and get a crossing there.”

“Yeah, good plan,” he said perkily. “How far is that?”

“Oh,” I mused, “it’s about the same as going to the fucking moon in that truck.”

Twenty-eight hours later, dazed and confused, we pulled up outside my sister’s place in Shepherd’s Bush. Then we went to the pub. James somehow made it back to his place in Primrose Hill that evening, although he went a little mad, locking himself out and losing his takeaway curry.

The next day, with help from France and her fiancé Matt, I emptied the contents of the truck into a storage facility in Fulham. I grabbed a suitcase of clothes and locked the door. Everything I had from the last nine years of my life in France was padlocked away in that warehouse.

Ten months earlier, I’d celebrated winning the world title by flying to Las Vegas and partying in a suite in the Bellagio. Now home was the floor in my sister’s living room.