My sixth month of confinement in the AC was difficult. Reflecting on the choices I made that brought me to this point only magnified my sense of loss. Time dragged by as I anticipated the upcoming warden’s committee scheduled for the end of the month. Would they deny me yet again? I dreaded the possibility of spending another three months in the AC before another committee review.

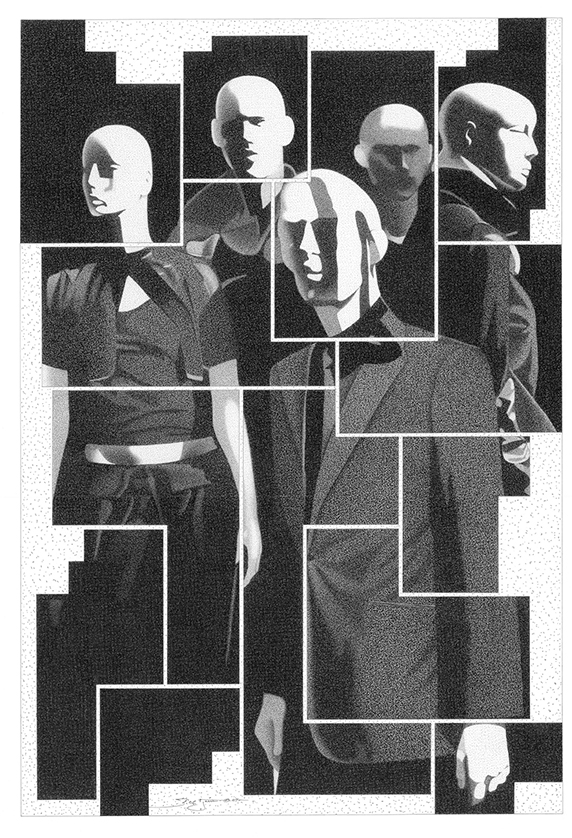

I spent almost every waking moment creating compositions on paper, and as my desperation grew so did my intensity and feverish pace. I became a madman with a driven sincerity. Sheets of paper with compositions and drawings in all stages of completion covered my cell walls. Even more drawings were under my mattress. My work began to reflect a distinct undertone—darkness. My photo-realistic nightmares and dreams lay before me as if my mind’s wanderings and demons were taking on a life of their own.

My subconscious spilled over into my waking hours, and when I wasn’t drawing and recreating my mind’s pictures, I entered into a visual dialogue with the paintings of the artists I read about.

My dreams are a series of stark black-and-white images, like an old silent movie. Each image is like a picture cut out and placed in my view, followed by another, and then another. I’ve never heard of anyone else who sees dreams like this, but I always have, and always in black and white.

Even though condemned prisoners are not allowed inside the San Quentin Library, I have requested and read every book there regarding art. My art education is extensive, largely from studying those books, alongside my endless passion for expression. My art education is extensive, largely from studying those books, alongside my endless passion for expression.

A bull keyed the AC speaker and announced, “10-12 in the unit.” This is the code for a high-ranking official, and announcing it alerts all the bulls in the unit to be awake and put any contraband items in their lockers so they are not caught. I was so engrossed in my study I didn’t notice the warden and one of his captains had entered the tier where I lived.

I had my headphones on when they came by my cell. Engrossed in Robert Motherwell’s writings, I only noticed the group after a flashlight beam crossed my eyes to get my attention. I took off my headphones and stood up. Warden Vasquez, along with the captain, Heckle, and Jeckle, were standing outside my door looking at me.

“Morning, gentlemen, how can I help you?”

“I had the opportunity to take a look at your work on the wall of my quiet cell. I am very impressed by your talent. I’ve never seen anything like it. The detail and overall feel of the mural is enormously powerful.”

I didn’t say anything, and the warden continued.

“I see you’re condemned, so you’ll soon meet my committee for review. When you are given your grade-A status, I expect you will continue what you are doing. Do you do portraits?”

“I can draw anything I can see in here.” I pointed at my head.

He looked closely at all the drawings and compositions on my walls.

“Impressive. As a grade-A prisoner you will have the chance to participate in the handicraft program and you can get art materials. I’m sure you will sell most, if not all, of your work, since you’re the best I’ve seen.”

“I look forward to that. However, your committee has turned me down twice, and I fear the same will happen again,” I said.

“I believe things will be different this time. My staff tells me you are no trouble and always address them with respect.”

“I try to treat everyone with respect, like I want to be treated.”

“Words to live by. I’ll let you get back to your work. I look forward to seeing you soon, Mr. Noguera.”

“Good day, Warden Vasquez.”

“Ah, good day, Mr. Noguera.”

They all turned and left. I stood there for a moment replaying the conversation in my mind. Had he just told me I’d get my grade-A status? My concentration was broken when my neighbor, Blue, called me to the bars.

“I heard what them bottle stoppers said. Looks like you’ll be getting that grade-A real soon, old son.”

“I don’t know, bro, I’d hate to get my hopes up only to get them smashed.”

“Nah, I know Vasquez. That old bull is pretty straight up, and he likes your work. I’ve checked out that mural you did in that cell back there, and so have a lot of these bottle stoppers, and every one of them leaves saying you’re the best they’ve ever seen, and I agree. That thing you do with an image is far beyond skill and talent. It’s magic.”

“Yeah, now you’re blowing smoke up my ass. What, you need a drawing for that fine twist and twirl you’re writing?”

He burst out laughing.

“Yeah, I’d love another drawing, but the truth is what it is.”

“Man, I’d really like to get over there to East Block and call my family.”

“Them cats over there get on the moan and groan, yard, and leaning tower every day. Plus, you’ll be able to get in that art program.”

“The warden mentioned I’d be able to sell my work. How does that work?”

“They got a gift shop just outside the main gate where you can put your art, and bulls and the general public can buy it. There’s also a specialized contract the warden’s office puts out, so if a bull wants something special you and him can enter into a contract. You do the work and he pays. I have a feeling you’ll have a line in front of your cell waiting to buy your work.”

“Yeah, that would be something. I’d like to be able to support myself and send a bit home to my family.”

“Man, I’m going to miss having you as a neighbor when you’re gone.”

“I’m not gone yet. For all you know, I’ll be here another year.”

“I doubt that, old son. I’ll get at you later.”

“All right, take it easy,” I said.

Those few but powerful words from the warden brought a light to the darkness. I imagined what I’d encounter in East Block and what I could accomplish there. I didn’t completely understand what lay ahead, but I started to form an idea that could utilize my mind’s potential and the potency of my work. It could possibly restore the inner freedom lost during a lifetime of pain and mistreatment.

As my date with the warden’s committee approached, I tried to occupy my mind with work, exercise, music, and yard every chance I got. The committee was constantly on my mind. I was nervous, excited, and anxious to get an answer.

I paced back and forth the night before my hearing. I tried to sleep, but it was impossible. Sleep would not visit me that night. Instead, thoughts raced until an old enemy awakened.

I’ve been haunted by migraines since I was a small child. At times, they were so bad I’d throw up and have to close my eyes. Any light caused immediate pain so intense that nausea overwhelmed me.

I remember holding my head with my hands, and rocking back and forth when one of the headaches assaulted me, the whole time wishing I could break open my head to relieve the pressure and pain that throbbed like a heartbeat.

The headaches continued into my adult life. Anxiety was normally the precursor that set them in motion, subsiding only after hours or days of torture. I tried to relax as the headache came on. I washed my face in cold water and laid down on the concrete floor of my cell to meditate, using thoughts of the ocean and the joy it brought me.

The memory helped me relax and sleep came. There were no dreams, just sleep.

I woke suddenly. The headache had receded like an ocean tide. My cell was completely dark, but I could see the sky from where I lay on the floor. From that angle, I could see out the tier windows about fifteen feet from my cell. The sky took on a purplish glow. It was Wednesday morning. I had only slept about forty-five minutes, but I was ready.

After a bird bath I wrote out the points I wanted to make to the committee. As I waited to be called I wondered if my notes would do any good. Was I fooling myself? Had the committee already made up their minds? Was it all just a formality?

John Wooden’s famous words came to mind: Failing to prepare is preparing to fail.

At 9:45 a.m., Heckle and Jeckle came to my cell.

“You ready for committee, Noguera?”

“Been ready.”

“You know the drill.”

After the standard strip procedure they escorted me to the hearing, where the warden sat with the same captain who had come by my cell earlier in the month.

The change in mood was obvious from the moment I entered the room. Both the warden and the captain nodded to me in recognition.

“Mr. Noguera, please sit down.”

I sat and the warden began.

“Good morning. As you know, we are here to review your possible entry into the condemned grade-A program. Since your arrival at San Quentin you have been housed here in the AC for observation because of your possible attempted escape from the Orange County jail, as well as your violence on a number of occasions while you awaited trial. My staff and I have interviewed a number of prisoners and the officers who work your tier.”

As soon as he mentioned other prisoners, I feared someone told him about the incident on the yard with the Northern Mexican sleeper. That would be a reason to deny me grade-A once again.

The warden continued. “Everyone we interviewed told us you are not a gang member and have no ties or affiliation to any gang. Further, you have received no write-ups in the seven months you have been with us. In essence, you have done everything asked of you. Before I conclude this hearing, I’d like for you to consider the following. I have seen many men come to my prison with artistic talent. Granted, not many with the talent you possess, but I’ve checked up on them years later, and they used their talent to tattoo other prisoners or to create just enough art to support their drug habit. The question is, will you be different? When I check up on you, what will I discover? Will I find what I always find, or will you be that one I’ll never forget? Any thoughts, Mr. Noguera?”

“I’ve thought carefully about this moment and what I’d say to you, and I realize many men have come before you with words full of promise only to fail. I won’t make promises to you. My actions will speak for themselves. I’ll leave it at that and I’ll thank you for your consideration.”

“Nicely put, Mr. Noguera. Associate Warden, anything else?”

The associate warden turned to me. “I’ve been working at San Quentin since I left the Marines when I was twenty-three years old. That was over thirty years ago. When the warden said I should come to the AC to look at something a prisoner had drawn, and that I should bring my son who is also an officer here at the prison and who recently graduated from art school, I didn’t know what to think. I’ll tell you something, both my son and I were deeply moved with what we saw in the quiet cell. We also went to your cell while you were outside and examined your drawings and compositions. What you possess is a gift. What you do with it is entirely up to you, but mark my words, in thirty years in CDC I’ve never seen anyone like you.”

The warden then spoke. “It is the decision of this committee that you, William A. Noguera, CDC D77200, will receive grade-A status and will immediately transfer to East Block. You are assigned to Yard-1. I hope you appreciate this chance and take full advantage of it. If you come before this committee again, I promise you I will make it a point to keep you in the AC until I retire. Don’t forget that.”

“I won’t, Warden. Thank you for this opportunity.”

Finally. I’d get my chance in East Block. They took me back to my cell and Blue was waiting at the bars. He waited for the cuffs to come off and the two bulls to leave. Then he called.

“Bill, what happened?”

“Vasquez gave me a shot. I got my grade-A status. They said I’m going to East Block immediately.”

“Man, old son, that’s all right. Listen, they’re not going to come for you for a couple of hours, so pack up your stuff and then holler at me. I have a few things I want to run down to you before you leave.”

“Right on. Give me a few and I’ll be with you.”

I turned and looked at the cell I’d lived in for the last six months. There wasn’t much to it. Most of the things were state-issued, except my shoes, small radio, headphones, drawings, and hygiene items. I quickly gathered my personal things and placed them all inside a pillowcase. I felt like I’d just won the lottery.

As I think of that day now, I realize just how sad and pathetic it all was. Nothing had really changed. I was still on death row, surrounded by killers, rapists, and child molesters. They’re the worst men in our society, all corralled together waiting for their execution date. Still, I found a silver lining in all of it. I would not waste the opportunity.

I placed my pillowcase with my property next to the cell door, rolled up the mattress on the bunk, and placed a few items on top of it for the next prisoner who would occupy the cell: soap, towel, bowl, cup, quarter tube of tooth paste, and three pencils. It wasn’t much, but that’s what I started with. I’d give the next man the same chance I had. When I finished packing, I stepped to the bars and said, “Blue, what’s up? I’m done packing. I didn’t have much. Do you need anything?”

“I appreciate it, brother, but I’m fine. I do want to give you a heads up about East Block and what you’ll find there.”

“I’m all ears.”

“Don’t be fooled about grade-A and what it’s supposed to mean. The men there are just as dangerous as the ones here, maybe more so, because they’re smarter and haven’t got caught. Keep your eyes open and don’t fall asleep. When you get there, a lot of people will know who you are because word travels fast and people talk. What happened on the yard with Jose is no secret. Some will like it, others won’t.”

He continued, “In East Block, every yard has over a hundred men and each one is integrated. You’ll have Crips, Bloods, Southern Mexicans, et cetera, mixed together, so stay on your toes. You feel what I’m saying? Trust no one but yourself.”

“Hey, right on. I understand and I appreciate you taking the time to tell me these things. Believe me when I tell you I’ve enjoyed having you as a neighbor and getting to know you. Is there anything I can do for you once I’m in East Block? Maybe make a call for you?”

“I’m good. I’m used to writing, so I really wouldn’t know what to do or say on a phone. Can’t remember the last time I used one. Hell, come to think of it, I’ve been in the hole so long I think I’d be uncomfortable using a phone. Can you believe that? Damn, this place has truly fucked up my mind.”

At that moment, I heard keys and footsteps coming.

“Noguera, you ready? East Block is here to get you,” said Heckle.

“Blue, that’s my ticket. My best to you. I hope our paths cross again under better circumstances. Until then, I have a little something for you,” I said.

“All right, Bill.”

I gathered my things as Heckle and Jeckle stepped in front of my cell. “Just get your things. We don’t need to strip you. You’re grade-A and no longer our responsibility,” said Jeckle.

“May I give Blue this small drawing?” I handed the drawing to Jeckle, who looked at it and then handed it to Heckle. He opened the tray slot and cuffed me behind my back.

When the door opened I stepped out on the tier just as Heckle handed Blue the drawing in between the opening in the cell door and screen.

“Old son, this here is a fine gift. Thank you. Best of luck to you and keep your head on your shoulders. It’s been a pleasure knowing you,” he said.

“Same here, Blue. You take care.”

With that, I turned and walked off down the tier where an East Block bull waited for me.

Heckle and Jeckle followed behind but were not their usual selves. They didn’t shout “Clear” or “Escort.” Getting grade-A status somehow made me less dangerous. It’s funny how that works in prison. The word of the committee can suddenly transform an animal into a human. That’s a trick even David Copperfield would envy.

The East Block bull took me out of the AC at 11:15 a.m. It was late September 1988, and as we walked I took in everything. Mainline prisoners wandered around freely, and as we walked by they stopped to watch me. They knew I had a death sentence and came out of the AC. Some nodded. Others just glared. This was San Quentin State Penitentiary, the most notorious prison in the United States, and I was headed for the main death row housing unit. The walk took a few minutes, but I didn’t mind. The buildings were old and showed serious neglect. I could smell the decay. This place was so different from the world I’d once lived in.

As we rounded the corner to East Block we passed a brass fire hydrant with a prisoner kneeling next to it in the process of shining it. It was the only thing that seemed cared for in the entire prison. The prisoner seemed in a frenzy as he polished it. The bulls laughed and said, “That’s Corky, he’s a nut. He doesn’t shower and no one will go near him because of the smell, but he spends all day polishing that damn fire hydrant. Looks nice, huh?”

Nodding, my thoughts returned to Blue. I don’t know why he came to mind. Something had changed in him over the previous couple of months, but at that moment I didn’t know what it was. Blue was one of the highest-ranking members of the Aryan Brotherhood. Some even said he was one of its original founders. I never asked him about it. It didn’t matter. To me, he was a good neighbor who often talked to me about his views of the world and San Quentin. At fifty-five years of age and after thirty years of a life term for murder, I saw something different begin to form inside him. He seemed tired of the dog-eat-dog world we lived in and longed for a normal life. He often spoke of washing and cleaning his soul and being reborn. As I neared East Block I wondered if he was looking at the drawing I left for him.

In it, I created the world he longed for. An island, where he was free and reborn, where the shackles of the burden he carried fell from his wrists and ankles, where childhood resilience and memory gives hope and a future.

We finally came to the huge iron doors of East Block. A sign at the top read, “Death Row.” The bull hit it with his baton. A small window at the center of the door opened and another bull looked out, then the doors swung inward.

“New arrival for the row,” my escort said.

“Name and number, convict,” said the doorman.

“William A. Noguera, D77200.”

The doorman wrote it in the unit log book and the other bull escorted me to the front desk.

“We have Noguera from the AC, where do you want him? He got his grade-A.”

“Place him in the holding cage while I figure out what cell is open and get him his bed roll and state-issue,” said the desk officer.

Once in the holding cage on the first floor, I studied my surroundings. The place was filthy. I gagged from the strong urine smell. Looking down on the floor, I saw water ran freely from an unknown source, and roaches seemed to materialize out of nowhere. I placed my pillowcase over my shoulder. I didn’t want to put it on the floor. I looked up into the East Block housing unit and couldn’t believe how big it was. There are six floors to it. Five are tiers with rows of fifty-four cells per tier on both the bay side and the yard side. The first tier on the bay side uses eight cells for the sergeant, lieutenant, and other officers. That leaves just forty-six cells on that tier. The sixth tier is for the property officers and storage.

It reminded me of a massive birdcage. It seemed to fit since there were hundreds of birds everywhere, even a few seagulls. The combination of the birds and the yelling prisoners made the noise truly deafening.

Water ran off the tiers like a cascade where men washed out their cells. It was a lot to comprehend. I had never seen anything like it in my life. It was a madhouse.

The desk officer announced over the loud speaker, “Third tier officer, bayside, you have a new arrival in the holding cage. Come get him.”

I looked up and noticed a bull coming down the tier. He was blond with a handlebar mustache, about six feet tall, two hundred pounds, and wore sunglasses. He came down the stairs, briefly checked with the bull at the desk, then came over to me.

“You Noguera?”

“Yeah, boss.”

“Is this all your property?”

“Yes, I didn’t get my state-issue yet.”

“We’ll get it on the way up. My name’s Stevenson and I’m the third tier bayside officer. You’ll be living in cell-83. Let’s get you settled in.”

I turned around so he could cuff my hands behind my back. Stevenson opened the cage door and we went to the laundry exchange next to the front desk. He grabbed three sheets, three towels, three boxers, three shirts, two wool blankets, and two pillowcases.

“Everything came in new yesterday, so let’s load you up,” he said.

After getting everything I needed, we climbed the stairs to the third tier, and into cell-83.

“The cell’s clean, but I put a few extra towels in here, plus soap and scrub pads in case you want to wash the cell. Shower days are Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday, but if you go out to yard, you can shower out there every day. What yard were you assigned?”

“Yard-1,” I said.

“You’ll be allowed out every day to that yard. It’s a normal yard, unlike Yard-4, which is P/C (Protective Custody). They don’t go out on Wednesdays.”

“Boss, what are the rules on using the phone? I’d like to make a call to my family. I haven’t spoken to them in over six months.”

“The tier phone man schedules all phone calls. Phones run from seven a.m. until ten p.m. The phone man is your neighbor. When he comes in from yard, ask him to schedule you.”

“Thank you,” I said.

Stevenson left and I looked at my cell. The first thing I noticed was how small it was. Approximately four by nine feet. I could stand in the center of it and place my hands on opposite walls. I could reach up and touch the ceiling. It was a box. A very small box.