— 10 —

THE REAL BANK ROBBERS

Imagine this. You’re sitting at your local bank, chatting with a salesperson about how to invest your retirement money, when a group of armed men burst in. They’re wearing trench coats, and one of them is obviously Keanu Reeves, so, you know, your typical Wednesday in LA.

“Whoa, you should, like, totally give me your wallet!” Keanu slurs at you while slow-motion cartwheeling around the lobby. You’ve seen a movie or two, so you recognize that a heist is under way—but there’s a twist. The bank robbers aren’t the real villains in this scene. That would be the nice salesperson sitting in front of you. The armed men just want your wallet. That’ll cost you $60 and the time and inconvenience of replacing your credit cards and ID. The bank wants your savings—specifically, a percentage of it, every year, forever.

The real bank robbers work for the bank.

THE POWER OF MORE

The main challenge for a young person who has just started full-time work is the art of “adulting.” Paying bills, finding a place to live, cooking, that sort of thing. For me, it was adjusting to the shock that the money I earned was mine to keep. That’s a whole lot of Cokes. It was mind-blowing.

Right out of college, my money management approach was simple. Income went into my checking account and was then reluctantly spent on necessities like food and rent. After six months, my contract job converted into a full-time position, and I learned about fancy things like employer-based retirement accounts (which we will discuss in chapter 12) that I was now eligible for. When I found out that my work would give me extra money with an employee matching program, I immediately signed up—and quickly realized I had to start making decisions about how to invest that cash. That’s how I found myself sitting down with a dude from my bank.

What he told me didn’t exactly inspire confidence. He kept recommending me this one mutual fund run by the bank but couldn’t answer basic questions about it.

“So, this fund invests in stocks?”

“Yes.”

“Which ones?”

“Those are determined by the fund manager.”

“How does the fund manager know which stocks to pick?”

“He uses an algorithm to select them.”

“Can I see this algorithm?”

“Unfortunately, no. It’s proprietary.”

“Okay . . .” I sat back in my chair, suspicion blaring like an air-raid siren in my head. “How do you know this manager knows what he’s doing?”

“Well, he runs a mutual fund, so he must be pretty smart.”

“That’s not answering the question.”

“What would you like me to do to convince you?”

“I’d like to meet him.”

The bank salesperson scoffed. “Yeah, that’s not happening.”

“So, let me get this straight,” I replied, reaching for my jacket. “You want me to trust my money to a person I’ve never met, can never meet, using a proprietary algorithm to pick stocks that will never be explained to me—”

“Look.” The salesperson bolted upright, sensing correctly that he was not making a sale today. “Most people don’t have a problem with this kind of setup.”

I walked out of his office and never looked back. One perk of being an engineer is that I’ve developed the habit of checking and double-checking the math before making any financial decisions. So I knew which products had the highest commission rates, incentivizing the banking officer to peddle them to unsuspecting customers. The mutual fund he was trying to sell me that day paid the highest commission of all. Not only that, when I dug in, I found that the fund I was being pushed toward “wrapped” multiple funds—all run by the same bank, each with its own manager—into one superfund! The superfund manager would have gotten a cut as well, and the salesperson would have gotten a commission on top of that!

How many people in this bank would have been leeching off my money if I had listened to him?

When Percentages Beat Dollars

Around that time, I noticed what might be the biggest difference between how lower- and middle-class people think versus how rich people think. The lower and middle classes are obsessed with adding to their wealth: getting an education or a higher-paying job, that kind of thing. Rich people are obsessed with growing their wealth. They generally don’t talk about how much they make as a dollar amount, but rather as a percentage of their net worth.

“I only make six dollars an hour!” a poor person says.

“I only made three percent last year!” a rich person laments.

When you’re poor, percentages mean nothing. Ten percent growth is meaningless when you have no money; after all, 10 percent of $0 is $0. The vast majority of investors are people like you and me: working stiffs trying to improve their savings, starting off with a few thousand bucks at most. A percentage point is worthless, because 1 percent of $1,000 is just $10 a year. Who cares? But to the people running these mutual funds, 1 percent is a lot of money.

An equity fund I just chose at random has a management fee of 1.7 percent; that is, they charge 1.7 percent of the net value of your investment to select which stocks and bonds to put your money in. To an individual customer, that 1.7 percent seems like no biggie, but here’s the thing: that apathy is the exact reaction the bank is hoping for. At the time of this writing, this particular fund had assets under management of $700,000,000. To them, 1.7 percent is worth almost twelve MILLION dollars each and every year. And each of those twelve million dollars is handed over by someone saying, “Eh, who cares about one point seven percent?”

Percentage points matter. That was one of the first lessons I learned from rich people that helped me to become one of them.

What Exactly Are You Paying For?

When I started learning about investing, I thought it was about picking individual stocks: grabbing up Apple shares at $10 and later selling them at whatever ridiculously high price they’re trading at now. But that felt uncomfortably close to betting on horses at a racetrack, and I do not, nor will I ever, gamble. I’ve seen firsthand how that particular vice can wreck people’s lives, and my dad taught me that it’s one of the most expensive addictions you can get; you can drink only so much alcohol before you pass out, but with gambling you can lose your entire life savings. So, stock picking never sat right with me.

That’s when I learned about index investing. I first heard about it from bestselling author JL Collins, author of The Simple Path to Wealth and founder of JLCollinsNH.com. I’ve since met Jim and had the opportunity to thank him in person for teaching me about this, because it was the first time investing ever made sense to me.

Every day people like us get up, brush our teeth, and go to work. That labor, whatever it is, makes money for our employers. No one can tell whether the work I do for my company is more valuable than the work someone else does for theirs. All we know is that money is being made. Index investing takes the guesswork out of trying to predict which company will rise or fall, and instead bets on the total growth of the stock market.

That, I could get behind. In any given race, I’d have no idea which horse is going to win or lose, so I’d never bet on any individual horse. But would I bet on the casino? Absolutely. Because no matter which horse wins or loses, the casino makes money.

Index investing allows you to bet on the casino.

Your Investments Can’t Go to Zero

What’s everyone’s biggest investing fear? Having all their money disappear, right? At least, that was my biggest fear—the guy in charge of my stocks picks a bunch that go bankrupt. Index investing doesn’t have this problem. Since the index owns all companies, it’s impossible for it to crash to zero. Individual companies may go bankrupt, but unless every single company goes bankrupt at the same time, the index never hits zero. (And if it does, the aliens have probably invaded, Independence Day style, and who cares about your 401(k) balance then?)

Index investing also has an elegant built-in barometer in that it owns shares weighted by market cap. In other words, if a company is worth more, the index owns more shares of that company, and vice versa. This is the most intuitive way of creating a gauge for the stock market as a whole, which is why most major indexes, like the S & P 500, which tracks the five hundred biggest companies in the stock market, are constructed like this. That means that when a company releases a cool new smartphone and their stock soars, the index will automatically pick up more shares. And when another company steps in it and their stock plummets, the index will dump shares. For the S & P 500, once a company drops in value from number 500 to number 501, it’s dropped from the index altogether.

JL Collins brilliantly described this as a “self-cleansing” mechanism, and that’s exactly what it is. Owning the index means you only own the biggest, healthiest companies and makes sure you get rid of shares of bad companies before they hit zero.

(Note that the only major American index not to use this methodology is the Dow Jones Industrial Average, which is price weighted rather than market-cap weighted.)

Index Investing Lowers Fees

One of the most frustrating things about evaluating actively managed mutual funds is that they don’t explain how they pick their stocks. They’ll throw around terms like “proprietary algorithm” or “high alpha and low beta,” but at the end of the day the fund manager’s not going to tell you because if they did they’d be out of a job.

The power of indexing is how simple it is. You could probably run an index fund yourself: just throw all the companies in the stock market into a spreadsheet, sort by market cap, and pick the top five hundred. Done. You’ve just created an index fund. And because it’s so simple, there’s no fund manager to pay.

In the United States, actively managed mutual funds charge MERs (Management Expense Ratio fees) north of 1 percent annually. In Canada, it’s even worse, with a typical mutual fund charging around 2 percent. But a typical index fund tracking the American stock market (NYSE: VTI) charges only 0.04 percent! That’s twenty-five times lower than the fee for an actively managed one.

The sneaky thing about management fees is that you don’t get a bill at the end of the year. If you did, you would say, “Wait, I have to pay a thousand dollars? For what?!” And then you would call up your bank for an angry conversation. Instead, that fee is taken out of your investments silently, every month. You never get a bill and you never see those charges broken out in a statement. That fee is baked in. The intent is to quietly take small amounts out of your pocket each month and hope you won’t notice. In fact, you can’t even see the fees unless you compare a managed fund to an index fund.

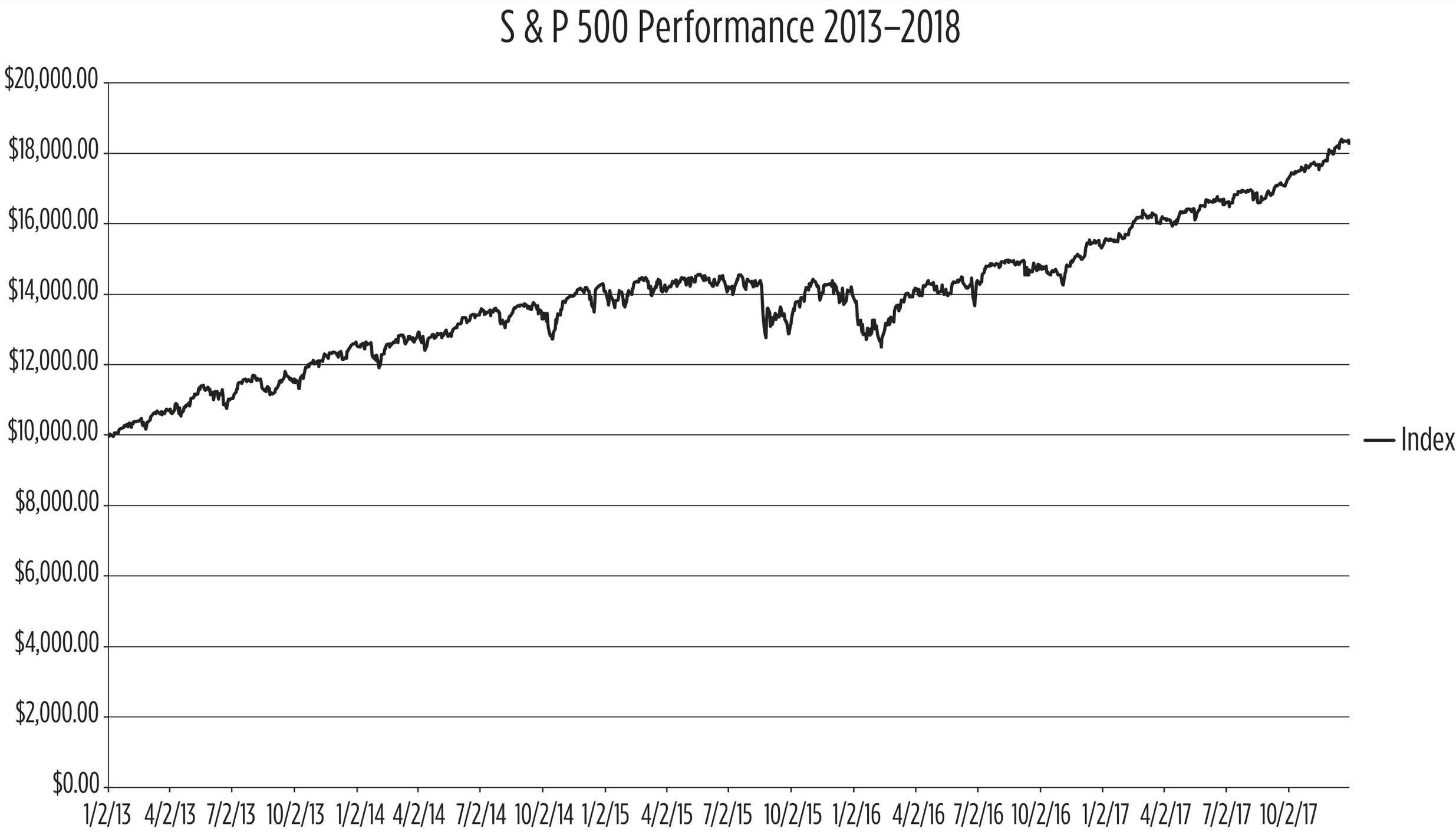

This is five years of the S & P 500’s price history, from 2013 to 2018:

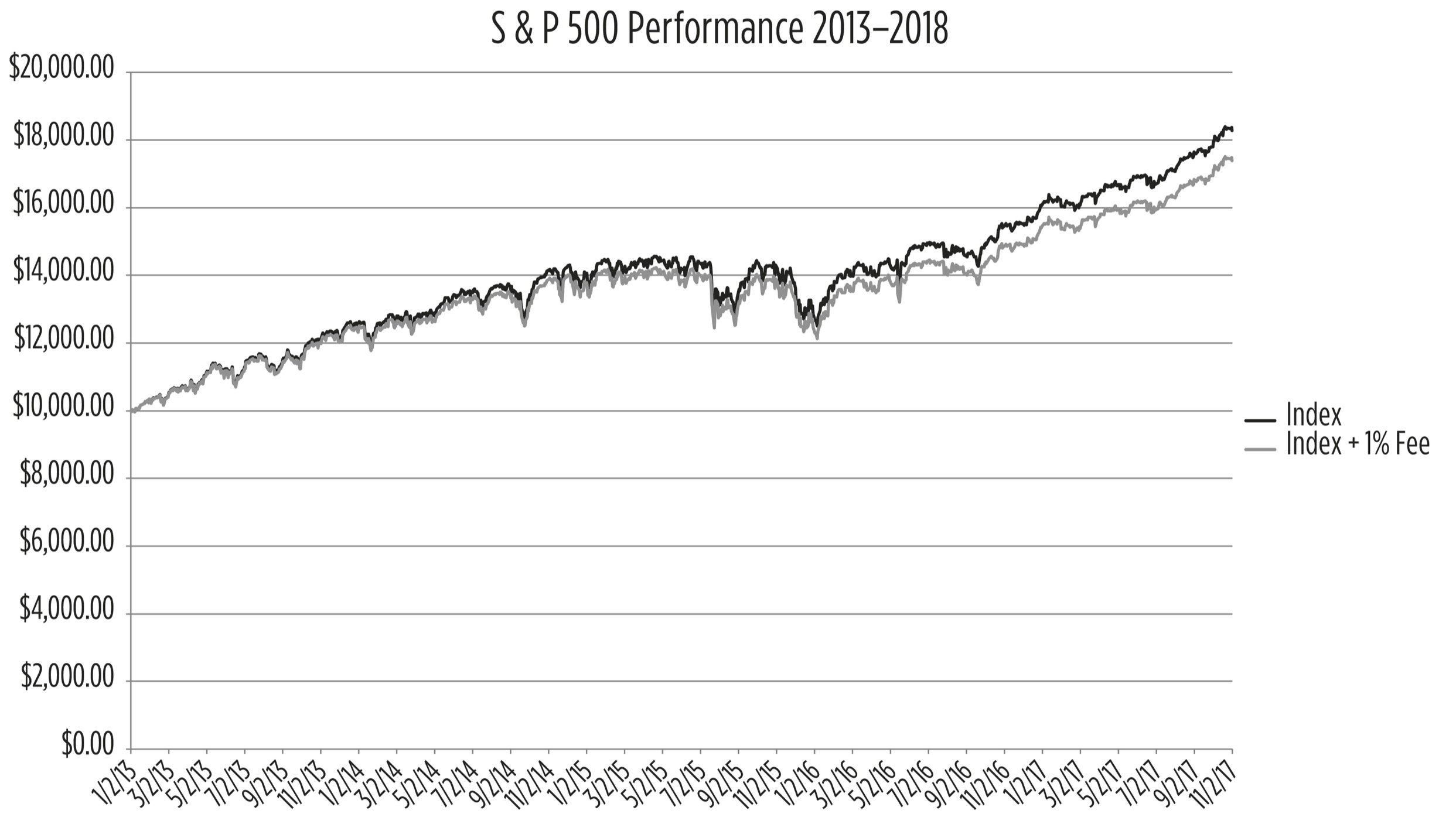

Now let’s see what would happen if we added a 1 percent management fee to this fund:

After five years, that 1 percent really adds up. For a person investing $10,000 at the beginning of 2013, they’re giving up $900, or almost 10 percent of their initial investment! Imagine how many cans of Coke you could buy with that! And this effect just gets worse as time goes on. One percent may not seem like much right now, but over a typical retirement time frame of twenty-five years, it snowballs.

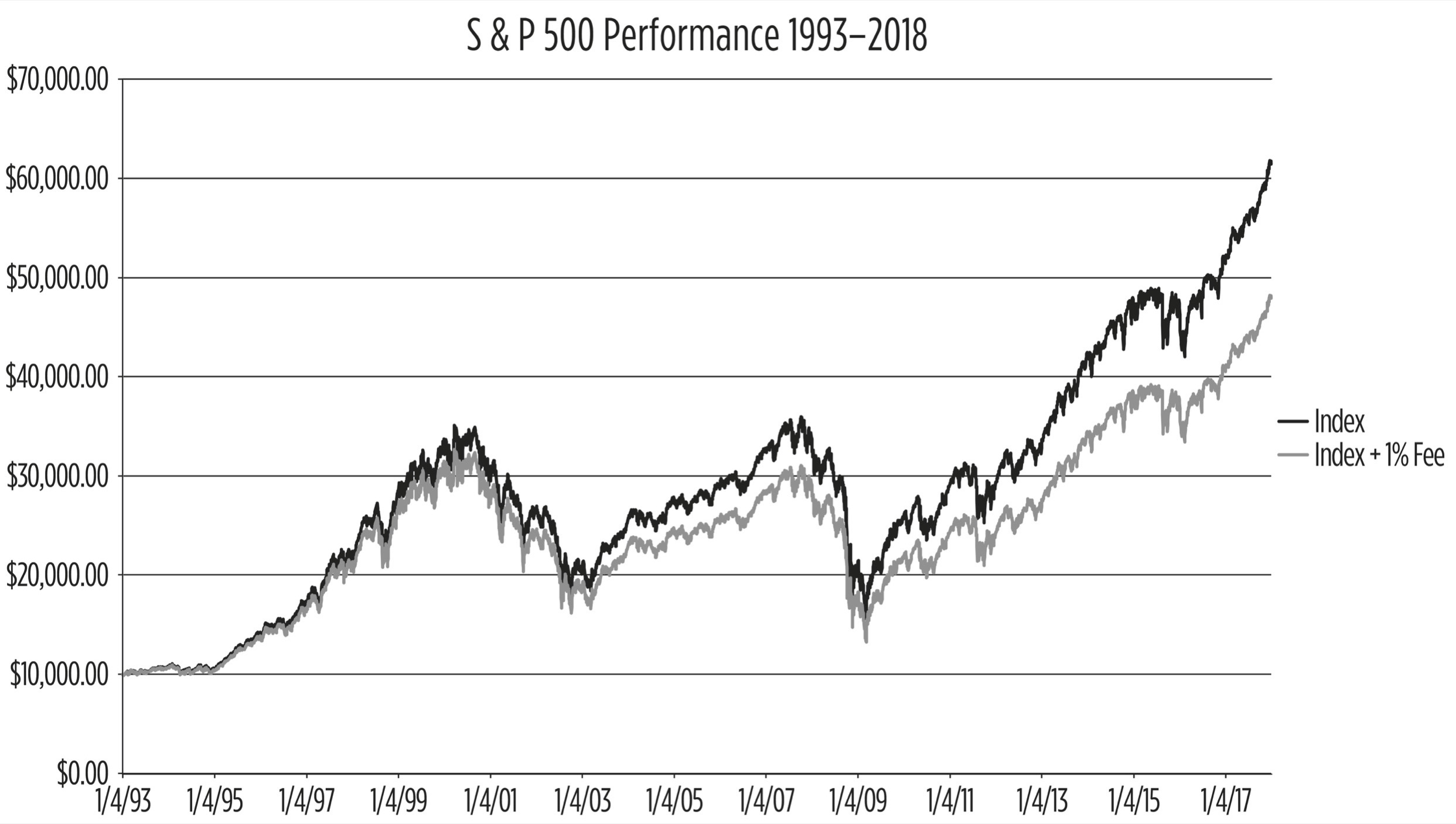

For that same person investing $10,000 over twenty-five years, this adds up to $13,500! This isn’t even Coke money anymore; that’s more than their initial investment!

Index Investing Beats Most Actively Managed Funds

And here’s the most infuriating part: those actively managed funds charging those high fees aren’t even good. If you were paying someone thousands of dollars to paint your house, you’d expect it to be painted. If you were paying someone thousands of dollars to fix your car, you’d expect it to be fixed. But just because you’re paying a mutual fund manager doesn’t mean they’ll make you money. They get paid whether their fund goes up or down.

Think about that for a second. If your job was to manufacture chairs, and on your first day you inadvertently started a fire, destroying some chairs, you’d have managed to manufacture negative chairs. Do you deserve to get paid? Probably not. Do you deserve to keep your job? Probably not. But that’s the deal many fund managers have. If they do a good job or do a bad job, they still get paid—by you.

And for all these fees, what value do you get? Turns out, not much. If you were to poll all active managers who are trying to outguess the stock market, you might expect about 50 percent to have beaten the index and 50 percent to have underperformed. But that’s not the case, and the reason is the management fees. Active managers don’t work for free. That means they have to beat the index by 1–2 percent just to make up for their own fees.

Would you like to know how many active managers manage to beat the indexes after fees in any given year?

Fifteen percent.

That’s right. Only 15 percent of active managers manage to beat their benchmark indexes after fees. And because there’s no reliable way to tell which of the active managers will turn out to be among that 15 percent, there’s no reliable way to pick which actively managed mutual funds will outperform—especially if the fund manager won’t even meet with you.

That’s when I realized it was really very simple. Index investing beats 85 percent of actively managed mutual funds.

How to Steal from Wall Street

If you ever want to see a banker sweat, try this: walk into your bank, ask to see a salesperson, and ask to put your savings into index funds. It’s the funniest thing ever.

Armed with the knowledge of why index funds outperform actively managed funds, I did exactly that. I had done my homework. I knew the literature and research cold; I knew the statistics. I had looked up the commission the salesperson would earn on an index fund: precisely $0. So, I was expecting an amusing spectacle.

And boy did I get it. That salesperson spun story after story about why I was making a huge mistake, and I slammed down chart after chart onto his desk proving him wrong. Eventually, he resorted to outright lying. This account, he claimed, couldn’t purchase those types of investments. But after I asked to speak to his supervisor, he relented. I got my account set up, and I invested in my index funds.

Here’s the deal: Wall Street hates index funds. Inside those shiny glass skyscrapers is basically a giant collection of stock traders. They have thousands of analysts working long hours, poring over the press releases and financial statements of every publicly traded company. They then feed this information in the form of tip sheets to traders on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange. Those traders then place orders based on that information. If that info suggests a company’s stock is trading below its true value, then the traders place a buy. If that info suggests it’s trading above its true value, they place a sell.

This is an oversimplification of a complex system, of course, but at the end of the day Wall Street’s job is to price how much a company’s shares are worth and to make money if they find a discrepancy. The effect of all this activity is the day-to-day movements of each stock’s price, as well as the overall movement of the stock market as a whole. Over time, this will cause a company’s share price to reflect what that company is truly worth.

However, someone has to pay all these people to do this work. That’s where actively managed mutual funds come in. By setting it up so the fund charges a percentage of all assets under management, and tricking investors into thinking that a percentage point or two isn’t a big deal, Wall Street manages to make money whether their traders guess correctly or not. The managers and their staff get paid—with your money—regardless of whether they do a good job.

Index investing is different. When you bet on the entire stock market, you are taking advantage of all the work those traders are doing trying to research and price out each individual stock in that index. And because there’s no fund manager, you don’t pay them or the legions of staffers who work for them.

When you use index investing, you are getting money back from Wall Street.

I left my bank that day with this strange sense of satisfaction. When I sat down in that salesperson’s office, he had every intention of screwing me. He was the robber.

But when I left, I was.

CHAPTER 10 SUMMARY

-

Index investing allows you to invest in all companies at once rather than trying to pick out the winners.

-

Indexes can’t crash to zero.

-

Index funds have lower fees.

-

Index funds beat 85 percent of all actively managed mutual funds after fees.

-