— 11 —

HOW TO SURVIVE A STOCK MARKET CRASH

I’ve been talking a lot about my life, and it might seem that I learned everything myself, but the truth is that my husband, Bryce, was with me through it all. We met in university as lab partners (nerd love!) and since then we’ve been navigating the big scary world of finance and adulting together. I’m mentioning him now because when it came time for me to put everything I’d learned together and figure out what exactly to do with our savings, Bryce saved my butt not once but twice.

I knew that index investing was the way to go, but selecting the right funds and designing a portfolio were different. The first means picking the best bricks in a pile; the second uses those bricks to build a house. Should we throw all our money into one index (S & P 500)? Spread it out among the Toronto Stock Exchange and international indexes such as the MSCI EAFE? What about bonds? Night after night, our account stared at us, all in cash. And I stared right back, paralyzed with indecision.

At the time, Bryce was earning his master of engineering degree at the University of Toronto and taking an economics course. While most of the material was dry and not useful unless you’re in supply chain management, one article jumped out at him. It was about the Nobel Prize–winning concept created by economist Harry Markowitz in the 1950s: Modern Portfolio Theory.

WHAT IS MODERN PORTFOLIO THEORY?

Modern Portfolio Theory says that assets boil down to two measurements: expected return and volatility. Expected return, measured as a percentage, is the expected annualized return of an asset. Volatility, measured as a standard deviation, is the day-to-day gyration of said asset. The higher the standard deviation, the more volatile the asset.

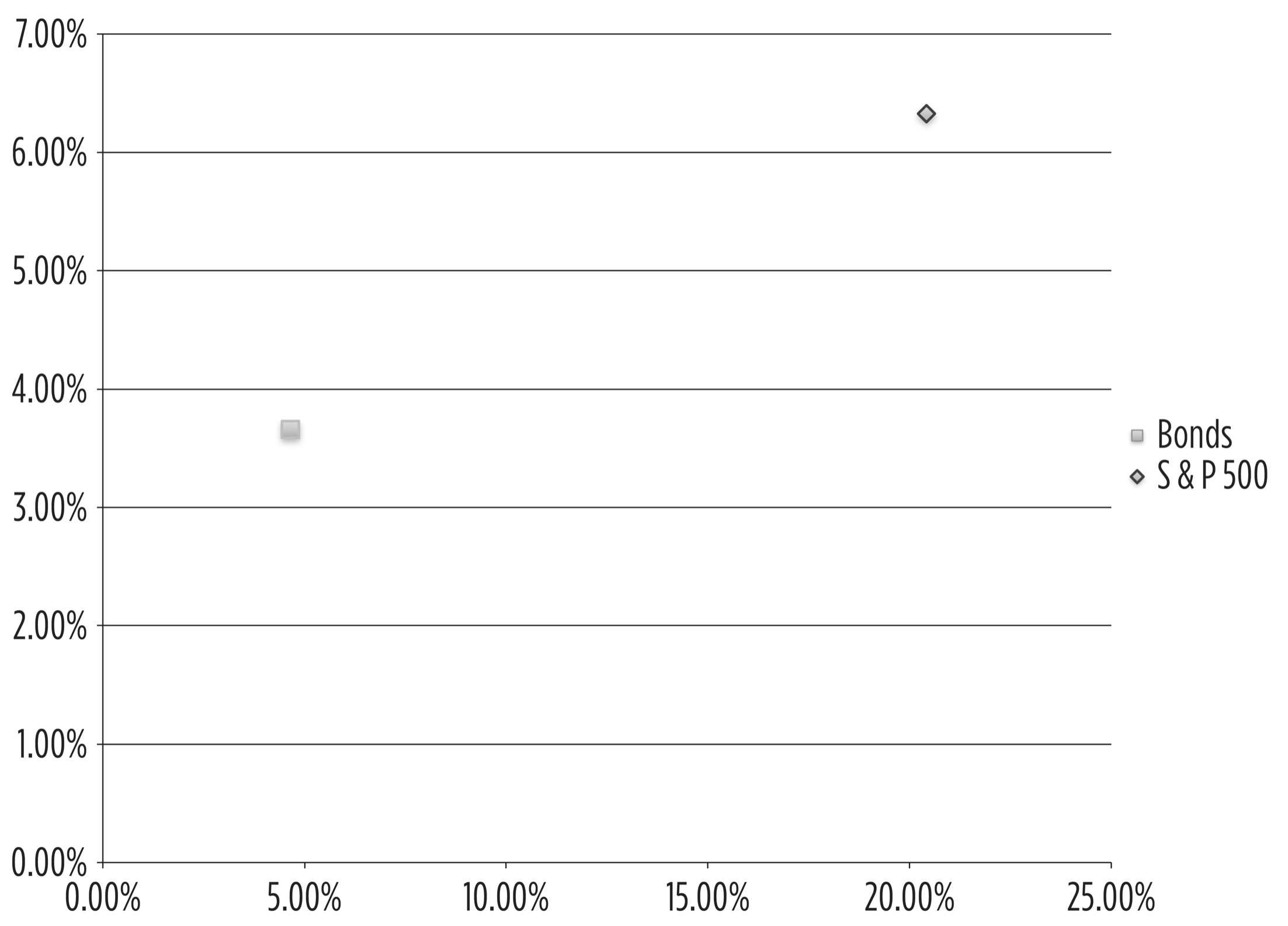

Let’s take two assets: equities, as represented by the S & P 500, and bonds. If we were to plot the risk/return numbers of these two assets, it would look like this:

On the vertical axis is expected return, and on the horizontal axis is standard deviation. The S & P 500’s position at the top right indicates that it’s a high-return, highly volatile asset, while bonds, on the bottom left, are lower return and less volatile.

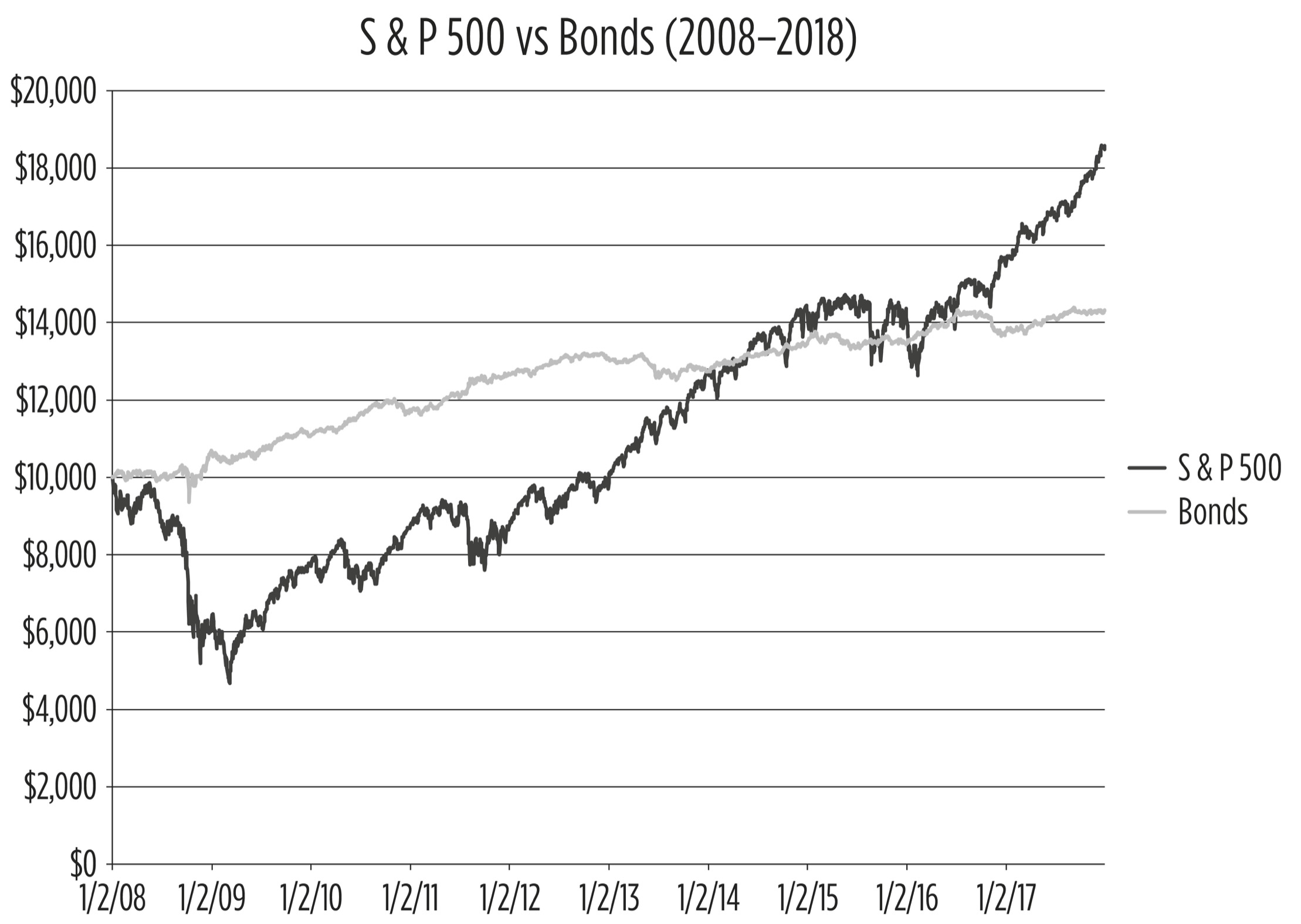

Let’s look at the day-to-day price chart of those two dots:

The darker line is the S & P 500; the lighter line is an index of bonds. Two things are obvious in this view. First, over time, the S & P 500 kicks the bonds’ asses. That’s the higher expected return of equities coming into play. Second, the S & P 500 is way spikier than the bond index. That’s the effect of equities’ higher volatility, or standard deviation.

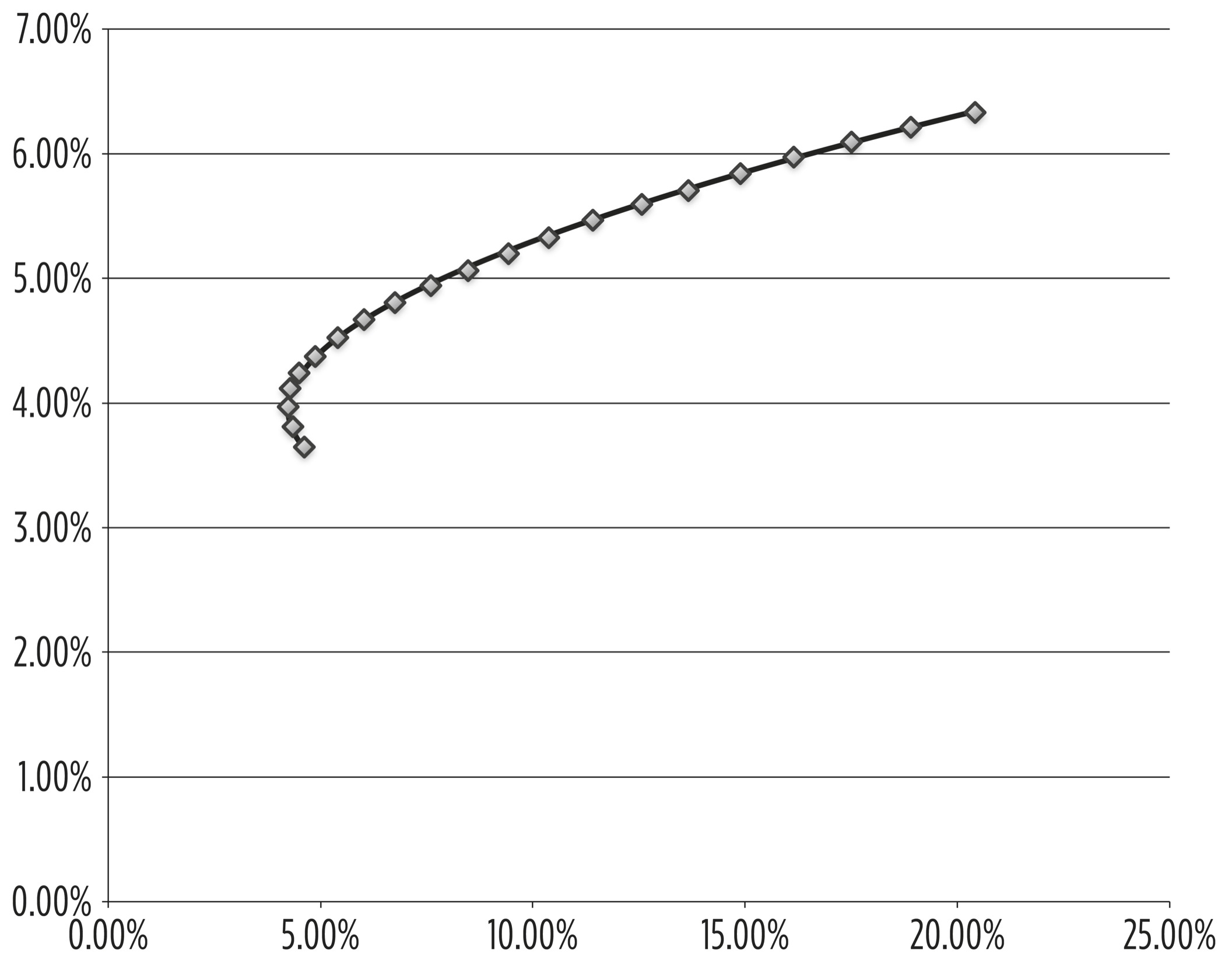

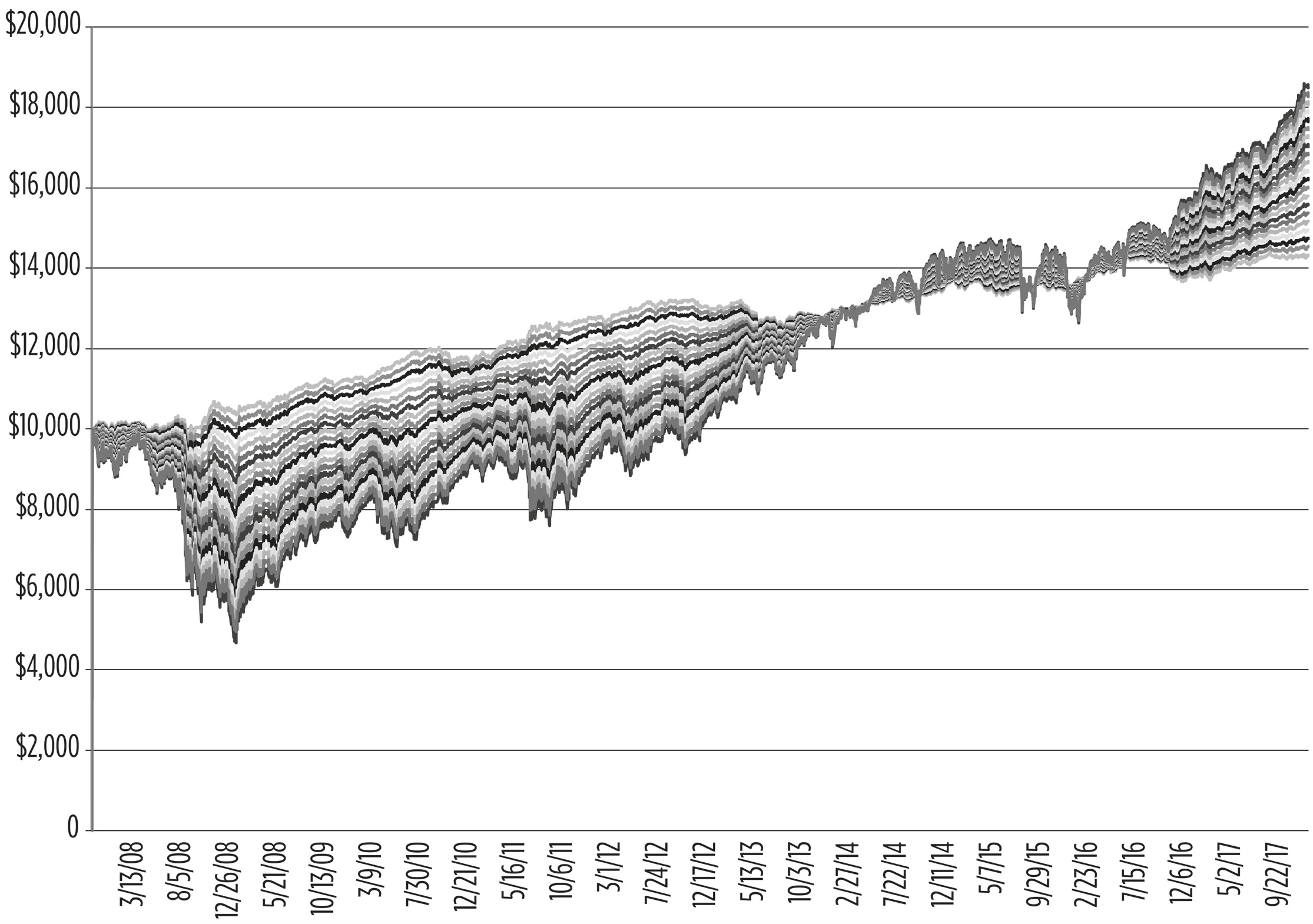

Now let’s see what happens when we create a portfolio that blends these two assets together. We will start with a 100 percent equities/ 0 percent bonds portfolio, then vary the percentages all the way until we arrive at 0 percent equities/100 percent bonds:

This is what Modern Portfolio Theory calls the efficient frontier, and if we were to look at these portfolios on our price chart, they would look like this:

This is the second key to Modern Portfolio Theory: every asset can be scored in terms of expected return and volatility, and you can control how much volatility you’re willing to take on by adjusting the percentages you allocate to each asset class. A higher equity allocation will result in higher long-term gains but a bumpier ride. A higher bond allocation will result in lower long-term gains but a smoother ride.

HOW TO DESIGN A PORTFOLIO

Learning Modern Portfolio Theory and combining it with index investing was my big “aha” moment. I finally understood how rich people think. Index investing was my way of accessing the stock markets safely, preventing my portfolio from dropping to zero, and avoiding the nasty management fees that would drag my performance down over the long term. Modern Portfolio Theory allowed Bryce and me to build an investment portfolio that worked for us. I now had a blueprint I could actually follow, and it went like this.

Step 1: Pick an Equity Allocation

The first major decision we had to make was how much equity versus bonds we wanted to hold, knowing that a higher equity allocation was going to give us higher long-term returns but a bumpier ride along the way.

Traditional investment advice is to hold a percentage of bonds equal to your age, like this:

|

Age |

Equity |

Bonds |

|

20 |

80% |

20% |

|

30 |

70% |

30% |

|

40 |

60% |

40% |

|

50 |

50% |

50% |

|

60 |

40% |

60% |

|

70 |

30% |

70% |

|

80 |

20% |

80% |

|

90 |

10% |

90% |

|

100 |

0% |

100% |

The idea is that when you’re younger, you don’t care about volatility since you don’t need the money right away. The compounding effect of the higher expected return of equities is more important. But as you get into your sixties or seventies, you care more about stability since you need the money to live on. Lowering volatility then becomes more important. Also, when you’re younger, your total portfolio is smaller. A 50 percent crash in value doesn’t mean as much when your portfolio is worth $50,000, for example, as when it’s worth $500,000 when you’re older.

Both arguments are solid, and they make sense, in theory. But there’s a problem. When you’re learning about investing for the first time, you’re inexperienced and nervous. The age-in-bonds rule operates under the assumption that people in their twenties will be okay with a 50 percent drop in their portfolio because they have a long investing time horizon.

Here’s a short list of people who aren’t okay with that:

Me.

So, while Bryce wanted to follow this rule and proposed an 80 percent equity/20 percent bond allocation, I was far more conservative and wanted to go 50/50. We compromised and set our initial target allocation at 60 percent equity/40 percent bonds, with the intention that as my comfort level increased, I would gradually increase it to our age-based target.

Starting at 60/40 turned out to be an unexpectedly good decision, and I’ll get to why that is in a bit. But first, on to . . .

Step 2: Choose the Indexes to Track

After you pick your overall equity/bond allocation, the next step is to choose which indexes to track. If you’re American, you’re probably going, “Well, duh, the S & P 500.” And in response to that, I’d like to introduce the concept of Home Country Bias.

Home Country Bias is the well-documented tendency of investors to overweight their domestic market. Now, before you accuse me of scolding Americans for thinking they’re the center of the universe, we all do this. Surveys show that investors all over the world prefer investing in their own countries, holding about 75 percent of their equity allocation at home. This is, understandably, because people tend to invest in markets they’re familiar with. In America, you can’t turn on the news without hearing about the daily performance of the Dow or the S & P 500, but you’ve likely never heard of the TSX (Toronto Stock Exchange) or the FTSE 100 (London Stock Exchange).

America is the world’s biggest economy, no question about it, so for Americans, the majority of your equity holdings should be American. However, that doesn’t mean you should ignore the rest of the world (we’ll get to why in a second). Fortunately, there’s an index that captures the developed world outside of the United States and Canada called the MSCI EAFE Index. MSCI is the company that maintains it, and EAFE stands for “Europe, Australasia, and the Far East.” Like the S & P 500, it works nicely as a market-cap-weighted index of the developed world outside of North America and is the oldest international stock market index out there, having been founded in 1969.

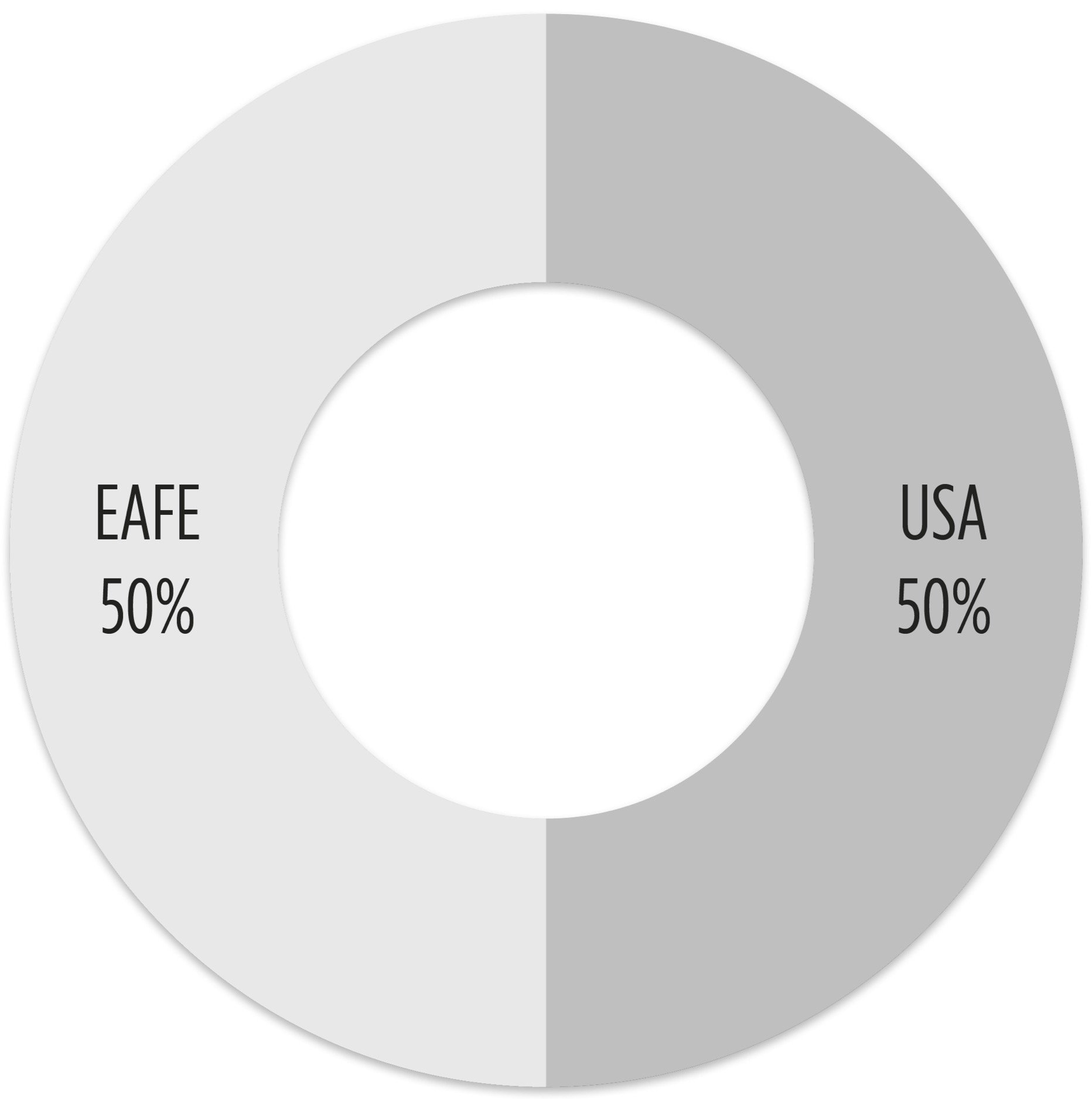

If we were to look at an index of international companies like the FTSE Global All Cap Index, which sorts companies all around the world by market cap, we’d see that the USA makes up about 50 percent. So, if we want to be globally balanced and reduce risk, we would pick an equity weighting representative of the US economic weighting relative to the rest of the world (50 percent US, 50 percent international).

If you live outside of the United States, avoiding Home Country Bias is even more important. America has been the undisputed economic powerhouse since World War II, and if Americans overweight their domestic economy and get it wrong, they won’t hurt their portfolio too badly. America is number one. At worst, they’ll fall to number two. Big deal. But for countries with smaller economies, the effect of overweighting domestic equities can be devastating, even though the temptation of investing patriotically is strong.

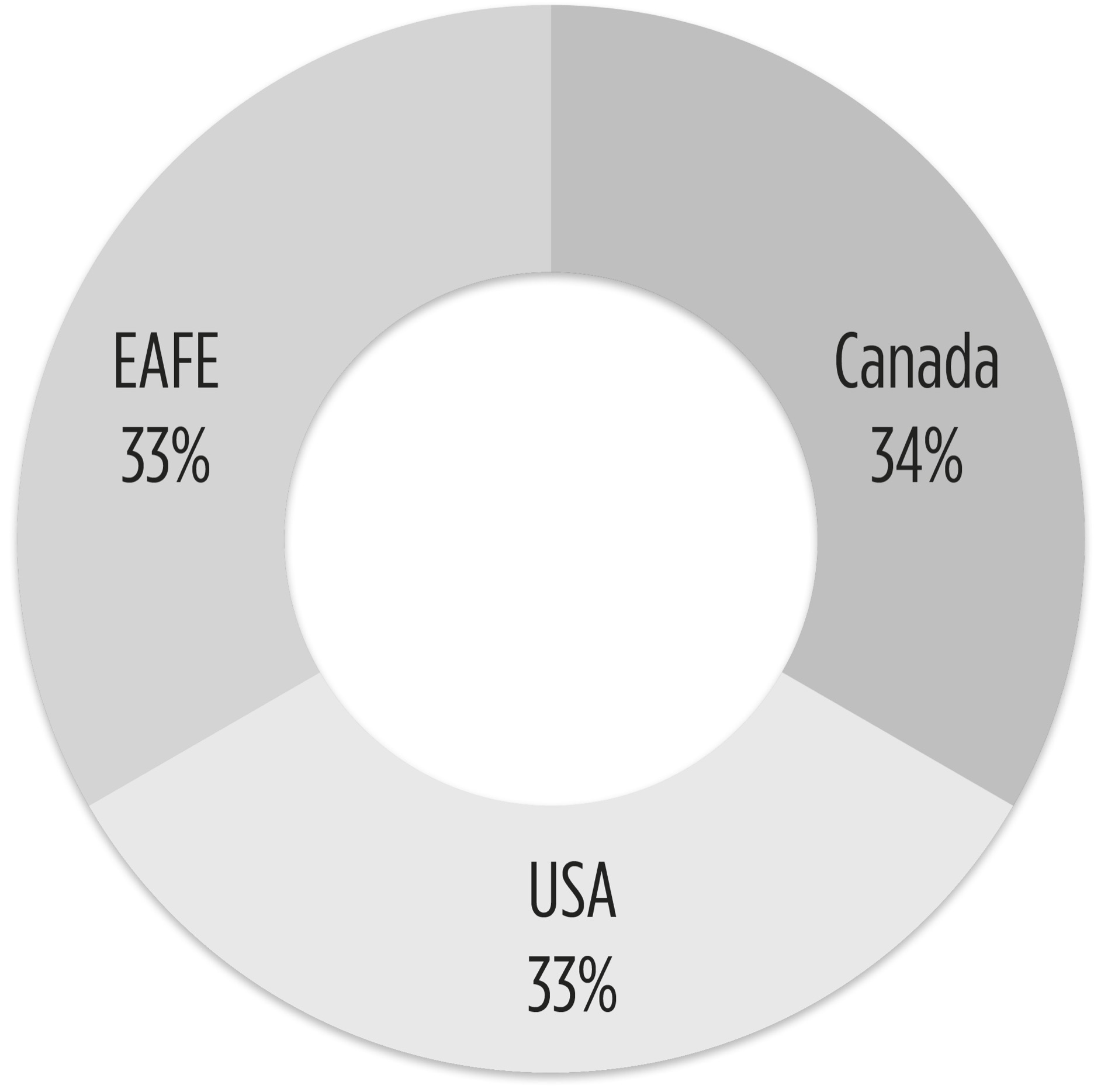

I love my adopted home. Canada has infinite Coke cans and zero Communists trying to murder my family! It’s fricking awesome! But when it comes to my finances, I have to remember that the population of Canada is about thirty-five million. California’s population is forty million. Our entire economy is about the size of one US state! So, I have to be realistic. Investing completely in Canada would be dumb, because we’re tiny compared to the rest of the world. But completely ignoring Canada doesn’t make sense either, since there are tax advantages that come with investing in domestic equities (which we will discuss in chapter 13).

Here’s the allocation we ultimately chose:

And again, this is a guideline. We went with this because:

-

We wanted the majority of our holdings to be outside of Canada.

-

We chose our US weighting based on its economic weighting vs. the rest of the world.

If you think one slice will do better than another, feel free to shift a few percentage points from one and add it elsewhere. If you’re right, you win. But if you’re wrong, you won’t decimate your investments.

Step 3: Pick Your Investment Funds

Once you’ve decided on which indexes to track and the weighting, it’s time to pick your funds. When we started investing, mutual funds were pretty much the only game in town, but nowadays there are much better options available. Specifically, I’m talking about exchange-traded funds, or ETFs.

ETFs are similar to mutual funds in that they invest in a basket of stocks or bonds, but unlike mutual funds they trade on the open stock market. This gives you two advantages:

-

They’re cheaper. When someone buys/sells units of a mutual fund, someone working at the mutual fund company has to process those orders and assign you the units. With ETFs, the stock exchange does that, and the process is automated by computers, so their fees (MERs) tend to be much lower.

-

Anyone can buy them. Typically, if you want to buy a bank’s mutual fund, you have to invest with that bank. This gives the bank many ways to screw with you, like charging all sorts of fees on your account. With an ETF, any brokerage account that can trade stocks, like Fidelity, Vanguard, or Questrade (for Canadians), can trade ETFs.

That being said, there can be one disadvantage with ETFs. Mutual funds typically don’t charge a commission per trade, but ETFs sometimes do, depending on your brokerage. This is because stock brokerages charge $5–$20 to execute a trade, while mutual funds bake that charge into their MERs. Back when we started investing, I was transferring money to our portfolio every paycheck (every two weeks), so my buys were frequent. This would have resulted in a lot of fees, so I opted for index mutual funds instead.

But these days, there are lots of brokerage accounts that offer free ETF trading. That means there’s little reason to use mutual funds anymore. So, what ETF should you buy? The cheapest one that tracks the index you want. As an index investor like me, you’re not shopping around for the fanciest fund manager. You know which indexes you want to track, so find the best index ETF with the lowest fee.

For a reference, here are some popular indexes and the ETFs that track them:

|

Index |

ETF Name |

Symbol |

MER |

|

S & P 500 |

Vanguard Total Stock Market |

VTI |

0.04% |

|

TSX |

BMO S & P/TSX Capped Composite Index |

ZCN |

0.05% |

|

MSCI EAFE |

Vanguard FTSE Developed Markets |

VEA |

0.07% |

|

US Bonds |

Vanguard Total Bond Market |

BND |

0.05% |

|

Canadian Bonds |

BMO Aggregate Bond Index |

ZAG |

0.09% |

Note that your employer’s 401(k) plan may not offer these specific ETFs. That’s okay. Simply pick the lowest-fee index ETF or mutual fund from the list of whatever your 401(k) provider has available. Then later on, when you retire or switch employers, you can transfer everything to a self-directed traditional IRA account and switch them for the ones you really want. We discuss this process in more detail in chapter 13.

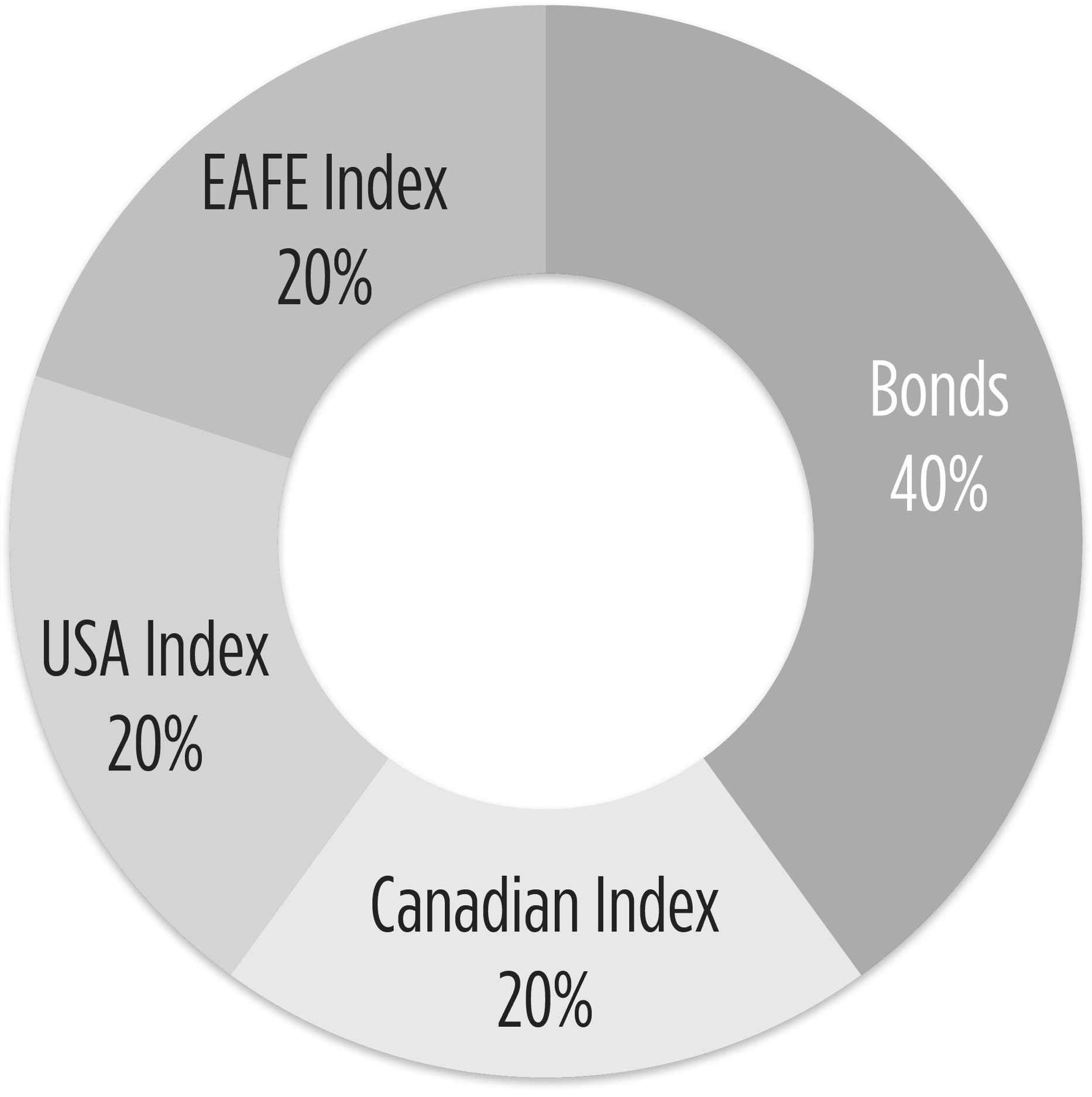

MY FIRST PORTFOLIO

So, there we were in our first apartment, two years into our careers, huddled around the computer with printed-out charts and papers scattered throughout our bedroom. The research was done, our portfolio designed, our investment funds picked out, and our combined life savings ($100,000) sitting in our brokerage accounts, waiting for their marching orders. Here’s the portfolio Bryce and I decided on:

It had a 60 percent equity/40 percent fixed-income asset allocation, with the equity portion split evenly among Canada, the United States, and EAFE.

“Ready?” Bryce asked.

“Yes. I . . . I think . . . ,” I stammered.

My heart raced. This was the first truly “rich person” thing I had ever done. I had gone from being relieved to have any money at all to learning how to grow it. The girl who dug for toys in a medical waste heap was about to invest in the stock market. But what if I screwed up? Would I squander every sacrifice my dad had made to escape the Communists for a better life in the West?

I knew I wasn’t making this decision lightly. I’d read the papers, I understood the research, and above all I trusted the math. So, with a tentative nod from me, Bryce put in the buy orders and together, we hit the Submit button.

Almost immediately, our portfolio went up.

It was only $10, but it was the first time I really saw how money could make money. During my childhood, money had been solely a tool for survival; now I understood how rich people saw it. This is how the rich get richer.

The next few weeks were magical. Every time we got paid, we put as much as we could spare into the portfolio and it kept growing. Soon I was up $100, then $500, then $1,000! I couldn’t believe it. Specifically, I couldn’t believe how easy it was. Why had I been so scared? I felt like an idiot for missing out in the past, but I was young, so I had plenty of time to ride this cash cow.

That night, as Bryce and I lay in bed, he asked me how I was feeling.

“Like a million bucks!” I felt like we had made it. We had learned the secrets of the rich; the sky was the limit. Dad was going to be so proud of me.

Before turning out the light, I checked my watch. It was just past midnight—on September 1, 2008.

THE GREAT FINANCIAL CRISIS

“SHITSHITSHITSHITSHIT!!!!”

“Everything okay?” Bryce called from the front door, having just returned home from work.

“No, everything is not fucking okay! Have you been paying attention to the stock market?!”

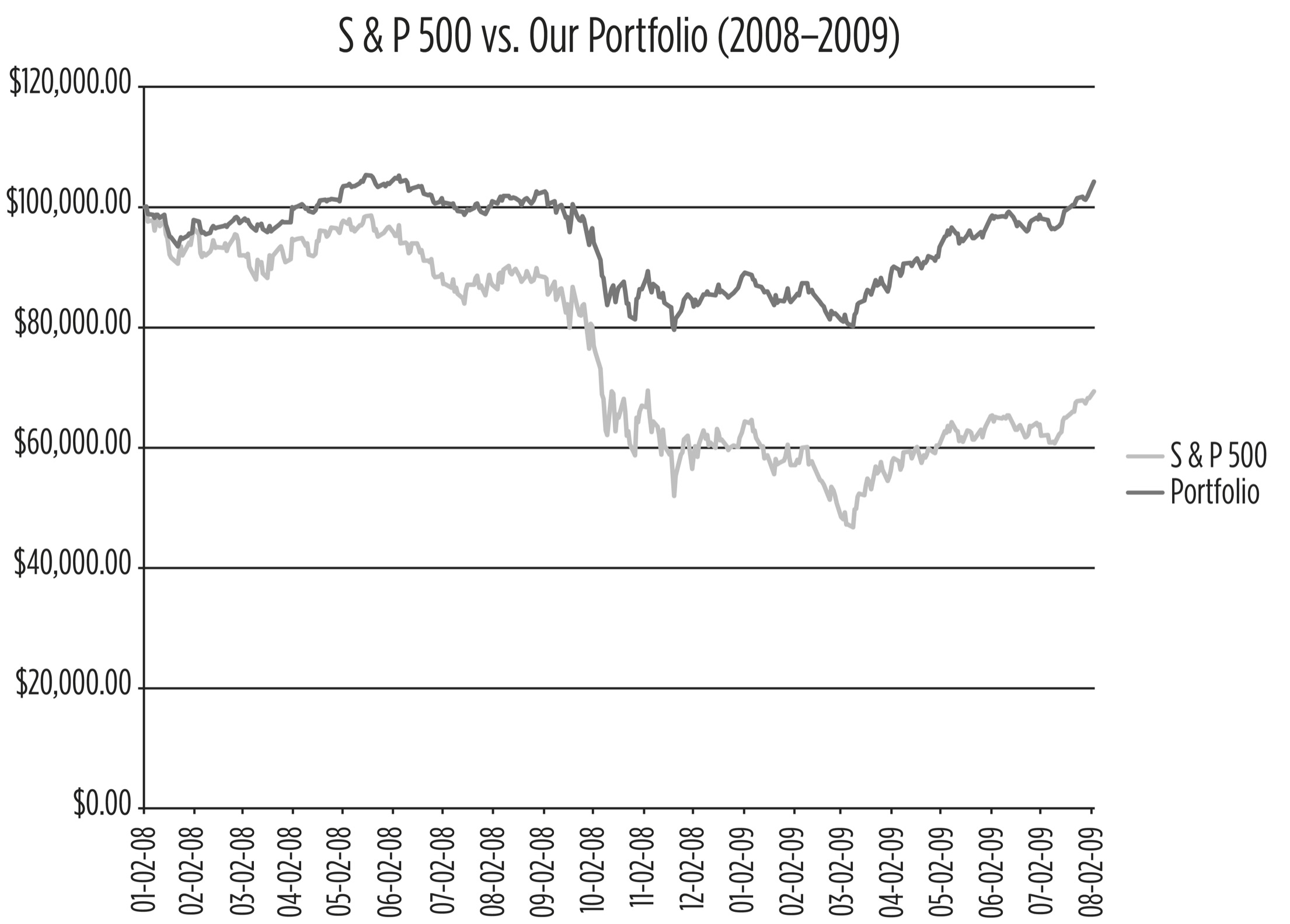

The Dow had just plunged over three hundred points, the papers had been screaming about something called the “subprime mortgage crisis” that I didn’t understand, and most important, we were losing money—about 20 percent of our portfolio. (See appendix B for details of our exact numbers.)

“So, it’s a down day.” Bryce shrugged. “It’ll be fine.”

I grabbed a copy of the paper and shoved it in his face. “This is not just a down day! Everything is not fine!”

“Okay, calm down, calm down,” he replied while making soothing ocean noises. “Remember, volatility is all part of the process. Sometimes there are up days, and sometimes there are—”

“You don’t understand!” I was hyperventilating at this point. “If you screw up, your parents will come save you. If I screw up, I’ll drag my parents down with me. I can’t . . .”

Now, I’m not going to pretend I’m perfect. Far from it. I’m pessimistic, I have crippling self-confidence issues, and I panic easily. All three traits were on display in that moment. And since he’s the eternal optimist in our relationship, that was the second time Bryce saved my ass. Because what I didn’t mention is that at the moment he arrived home, I had my finger over the Sell All button, and he managed to talk me out of it.

The next few months, unfortunately, didn’t help my anxiety at all. Two weeks later, Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy and the Great Financial Crisis was in full swing. Both the TSX and the Dow regularly dropped by more than a thousand points. I remember vividly losing $1,000 in a single day. That was more money than my entire neighborhood made back in China!

Bryce would wake up to find all the hair I had stress-shed overnight covering my pillow. He used to try to hide my own hair from me, so it wouldn’t stress me out even more, but I always caught him.

“What are we going to do?” I asked in bed after another day of watching our life savings plummet.

“You already know what to do,” he replied. “Go back to the research.”

Step 4: Rebalance

There’s a fourth step to Modern Portfolio Theory. It sounds relatively simple but there’s a lot of nuance behind it, and it saved us during the Great Financial Crisis. Here’s how.

Modern Portfolio Theory states that after you pick your asset allocations, you need to monitor how your holdings fluctuate over time, and if they start to deviate too much from your allocation targets, you should rebalance. So, for example, if my initial portfolio targets changed like so, then Modern Portfolio Theory would instruct me to do the following:

|

Asset |

Action |

Amount |

|

Canadian Index |

SELL |

2% |

|

USA Index |

SELL |

2% |

|

EAFE Index |

SELL |

1% |

|

Bonds |

BUY |

5% |

While this simple act of rebalancing may not seem like that big of a deal, it allows the investor to do some pretty clever things. First of all, it prevents you from permanently losing money. Stock markets may go up or down day-to-day, but over time the index always goes up. Since its inception, this is what the S & P 500’s performance has looked like:

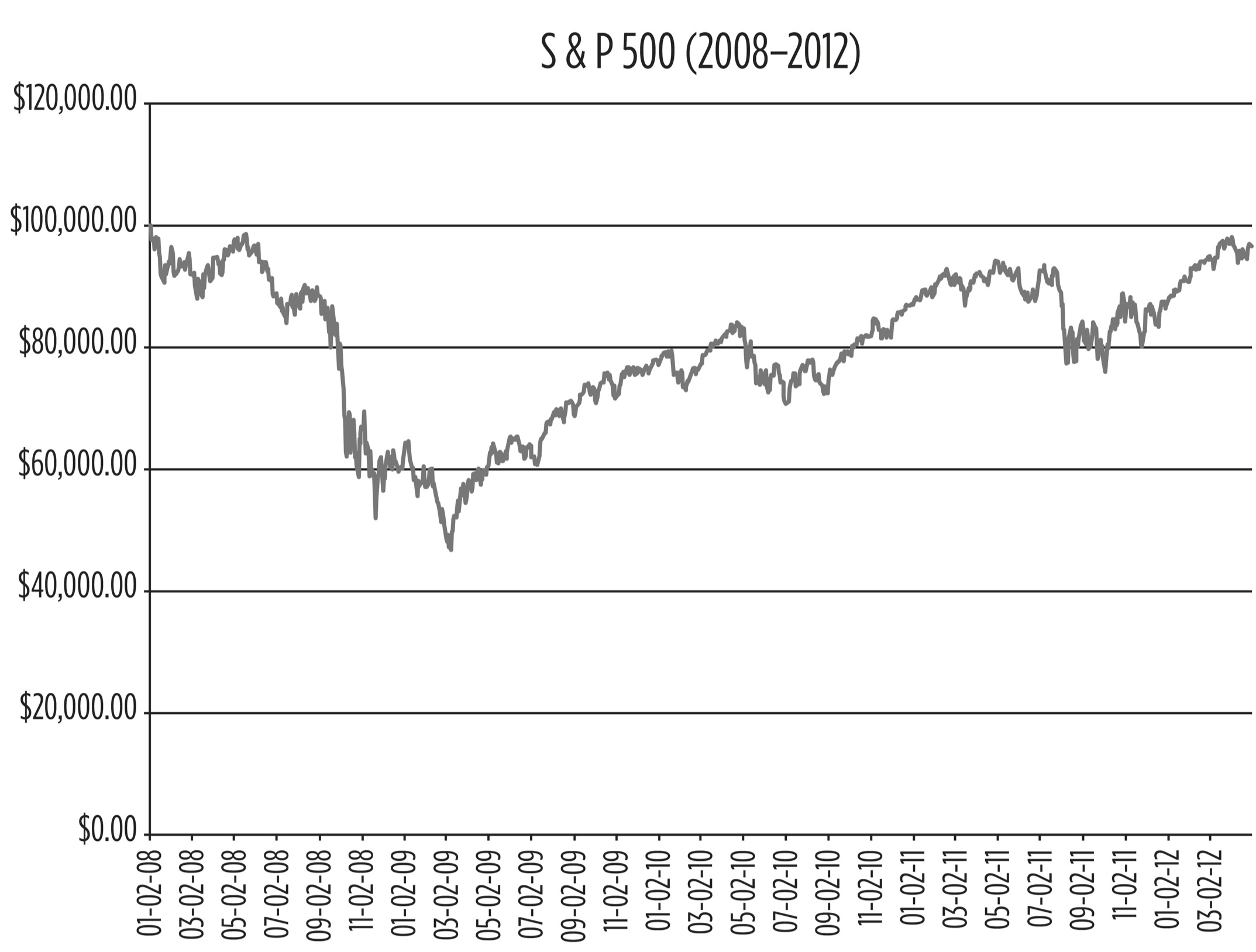

This period covers the Cold War, the Cuban Missile Crisis, 9/11, and every disaster that’s happened since 1950. The index recovered every single time. If an index investor is caught in a downturn, to get their money back, they just have to wait. I know this may sound counterintuitive—after all, when you see a dip, your natural instinct is to sell—but staying the course is always the smartest approach, which is what Bryce knew that day in 2008. The only way to permanently lose money would be to sell during a dip and miss out on the recovery. Rebalancing prevents you from doing this; you only sell an asset when that asset’s allocation is above target. In other words, you can only sell things that have gone up. You can’t sell things that have gone down.

Secondly, rebalancing enforces good investor behavior. Like I said, you’re only allowed to sell assets that have gone up. On the flip side, you’re only allowed to buy assets that are sitting below target. In other words, you can only buy assets that have gone down.

Buy low. Sell high. The definition of how to make money in the stock market.

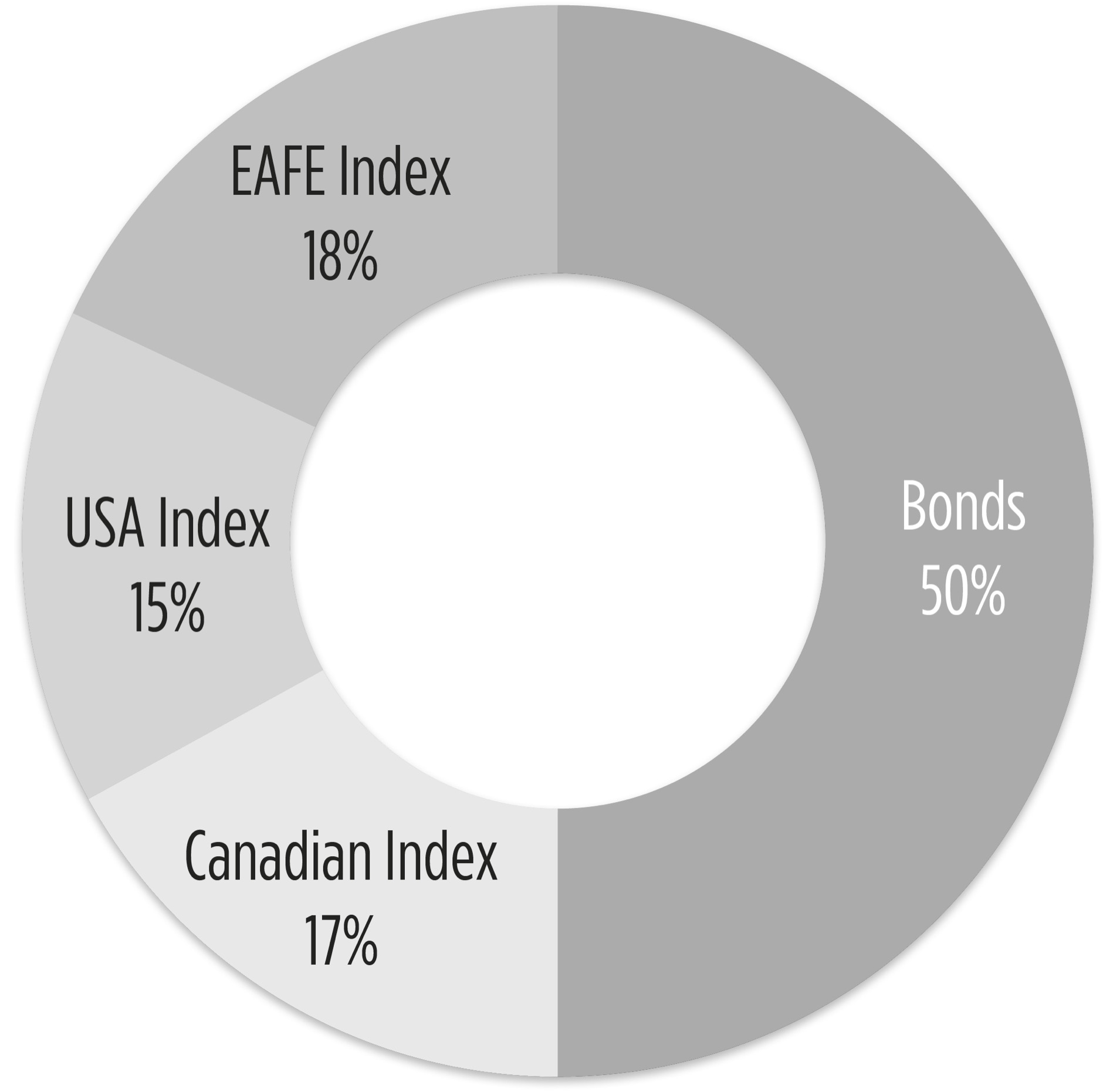

Finally, rebalancing forces you to ignore your two major investing emotions—greed and fear. And if it’s not obvious why overriding your emotions is important, let’s see what happens in a crash situation. During the 2008 crisis, every few days there would be another stomach-churning five-to-seven-hundred-point drop in the stock market. This caused my overall portfolio to go down since the majority of my holdings was in equities. But when I pulled up my asset allocation, it actually looked something like this:

Even though the overall size of my pie was shrinking, my bond holdings were going up! This is because in times of financial crisis, money flows from things that are risky (stocks) into things that are safe (bonds). Surrounded by alarming headlines and our dwindling portfolio size, every instinct in my body screamed at me to sell it all, run shrieking into the woods, and never invest again. Modern Portfolio Theory told me to do something different. It said to sell the only asset that wasn’t on fire (bonds) and buy more stocks even as the markets continued to plummet.

I didn’t know it at the time, but this turned out to be the exact right thing to do.

Limits to Rebalancing

Before I go any further, I have to warn you about a few limitations to this approach.

First, Modern Portfolio Theory only works if a portfolio has some fixed income as well as some equity. This system breaks down if you’re too tilted one way or the other. For example, during a stock market crash like the one we had, if I had been holding 100 percent equity, rebalancing wouldn’t work. As the stock market plummeted, there would have been no complementary asset that would rise, so my allocations wouldn’t have changed and I’d have had nothing to rebalance. That’s why I advise not going above 80 percent equity, even if you’re an aggressive investor.

Second, Modern Portfolio Theory works best if all your assets are in index funds. If there’s even a single individual stock in your portfolio, it could lead to trouble. While it’s impossible for an index fund to go to zero, it’s entirely possible for an individual stock to go to zero. And if that happened, rebalancing would guide you to sell off every other asset in order to buy more of the failing stock until it was all you owned and the company went bankrupt, swallowing your entire life savings along with it. Don’t own individual stocks in a portfolio that you plan on managing with Modern Portfolio Theory!

Surviving the Crash

As I stared at my crumbling portfolio, every instinct told me to cut my losses and run, but the research (and my boyfriend) was telling me to buy more.

Listening to the math and to Bryce had never let me down, so I went with them. Every two weeks, Bryce and I would pool our paychecks, figure out how much money we needed to pay for food and rent, and throw the rest at a stock market that was collapsing. One day, I bought $1,000 worth of index funds, only for my portfolio to immediately plummet by $1,000.

“Where the fuck did my money just go?” I yelled at the screen.

Even though it felt like setting money on fire, my ownership of those indexes was going up and up. I just couldn’t see it through my fog of panic.

It took until March 2009 for the market to find a bottom and start to rebound. Stock markets had crumbled around 50 percent peak-to-trough, but because our portfolio was only 60 percent invested in the stock market, our portfolio was down about half of that, 20–25 percent.

Here’s where things got interesting.

Because we had bought into the market as it fell, I now owned significantly more index fund units than when I had started, and at a significant discount. So I participated in the upside more strongly than the downside.

It took three and a half years for the S & P 500 to return to its pre-crisis levels in April 2012.

Here’s how long it took us.

Just two years into the Great Financial Crisis, we had completely recovered our money even though newspapers were still screaming about how screwed the world was. While Wall Street reeled, we emerged without losing a dime. With index investing and Modern Portfolio Theory, we had beaten most of the professional hedge fund managers at their own game.

The day that happened, Bryce greeted me at the door waving a pair of blue-and-silver pompoms.

“What? Why?” I demanded. That’s when he showed me our accounts, back at our break-even level.

“Whoa,” I exclaimed, dumbfounded. “It worked!”

CHAPTER 11 SUMMARY

-

Modern Portfolio Theory boils assets down to two metrics: expected return and volatility.

-

To design/maintain a portfolio:

-

Pick an equity allocation you’re comfortable with. We chose 60 percent equity, 40 percent fixed income.

-

Choose which indexes to track.

-

Pick the investment funds that track those indexes.

-

As your investments fluctuate in value, rebalance to your target allocation.

-