Published by Bretwalda Books at Smashwords

Copyright © Bretwalda Books 2011

This book is available in print from www.amazon.co.uk

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person. If you're reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

ISBN 978-1-907791-16-1

Historians tend to look back on the past with the benefit of hindsight. Things have a habit of seeming inevitable just because that is how things happened. Knowledge we have now can seem to be commonplace and obvious: RAF Fighter Command won the Battle of Britain; the Spitfire was a superlative fighter aircraft; the Germans did not invade Britain.

But for the people who lived through the past, things were very different. They did not know what the future held and they did not know what we know now. The people of Britain in the summer of 1940 did not know that they were going to defeat Germany. Every other country that had dared to stand up to German dictator Adolf Hitler had been crushed in a matter of weeks. The Aryan “Master Race” was starting to look like a reality. Hitler’s boastful gloating over his “secret weapons” that had seemed bombastic in 1938 now seemed to be fully justified as new models of panzers swept across France, new types of mines sank merchant shipping by the dozen and new types of bomber pounded cities to destruction.

It was into this maelstrom of carnage, destruction, secrecy and terror that the Heinkel He113 “Super Verfolgungsjaegar” (Super Air Pursuit Fighter) flew in the spring of 1940. Faster than the Spitfire, more agile than the Hurricane and more heavily armed than the Messerschmitt Bf109, the He113 was a “Super Fighter” indeed. It had the ability to dominate the skies. Hermann Goering, chief of the Luftwaffe, was quoted as saying that “The Spitfire is now just a pile of scrap metal.”

And yet today almost nobody has heard of this wonder. The Heinkel He113 Super Fighter has become Hitler’s forgotten secret weapon.

At 9am on 14 July 1936 a black car pulled up at the gates to Bentley Priory, a Georgian mansion built in the Italianate style that had been a girl’s boarding school until bought by the RAF. In the car was Air Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding. He had just been put in charge of the newly formed RAF Fighter Command and given Bentley Priory as his headquarters. Dowding was shown around the rambling house and chose his office. None of his staff had yet arrived, but the paperwork had.

Dowding’s prime task as head of Fighter Command was to defend the air space over Britain in the event of war with a foreign power. By 1936 it was becoming clear that if war came, then Germany was going to be the enemy. If Dowding was to turn Fighter Command into a war-winning organisation then he needed to know everything that he possibly could about the prospective enemy. Unfortunately, as Dowding took his seat in Bentley Priory, that wasn’t very much.

The Treaty of Versailles that ended the First World War had forbidden Germany to have an air force at all. Intelligence had reported that since coming to power in 1933 the Nazis had begun secretly forming an air force, the Luftwaffe. The key figure in the formation of the Luftwaffe was Herman Goering. Goering had served with distinction in the German air force during the First World War and then become a leading member of the Nazi Party. His prestige was instrumental in persuading Adolf Hitler to divert resources from his beloved army to the newly constituted Luftwaffe. Goering generally preferred to leave the hard work to others, but he had a real talent for spotting the right men for jobs and had a sound grasp of air power that enabled him to set the overall direction and pattern for the Luftwaffe.

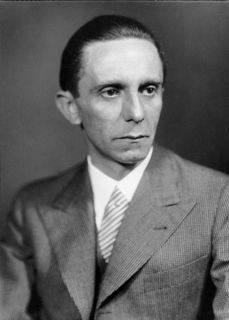

The formation of the Luftwaffe was, of course, carried out in absolute secrecy. It was a flagrant breach of the Treaty of Versailles and Hitler worried about how other countries would react — but the Luftwaffe, could not be kept secret for ever. In 1935, the new propaganda minister, Josef Goebbels, came up with a plan. The Luftwaffe would be announced to the world, but in the guise of a purely defensive force. It would be portrayed as a force dedicated to the defence of German air space against invaders. To this end, the announcement in the summer of 1935 that the Luftwaffe existed did not mention bombers, but concentrated on the new fighter the Heinkel He51.

Thus when Dowding sat at his desk in Bentley Priory, one of the first documents he read was the assessment from British intelligence of the He51. It did not worry him unduly.

The Heinkel He51 was a conventional biplane fighter of a type to be found in all air forces around the world. The frame was constructed of metal while the skin was of stretched fabric. The wings had two aluminium spars, while the fuselage was built around four steel tubes shaped into a rounded form by aluminium and wood spacers. The engine cowling was made of aluminium sheeting and could be easily removed to allow for engine maintenance. The best feature of the aircraft was the BMW VI engine, a V12 liquid-cooled powerplant that remained the main German air engine until 1938.

The performance of the He51 was average for the early 1930s. Nor was the weaponry outstanding, being composed of twin 7.92mm machine guns firing through the nose, and later models were adapted to be able to carry six 22lb bombs in racks below the wings.

Dowding knew that his RAF Fighter Command aircraft easily had the measure of the He51. The Hawker Fury biplane, which the RAF had in large numbers when the He51 was announced, had a top speed of 223mph, a ceiling of 29,000 feet and a range of 270 miles. Just entering service was the Gloster Gauntlet with a top speed of 230mph, a ceiling of 33,500 feet and a range of 460 miles. Its armament, however, was almost identical to that of the He51 being two 0.303in machine guns mounted in the nose. Another Gloster biplane, the Gladiator, was due to enter service in large numbers in 1937 and was even faster.

Moreover, Dowding knew that the RAF had on order three aircraft from a new generation of monoplane fighters that were expected to be the most advanced in the world. The first of these was the Boulton Paul Defiant. The performance of the Defiant was not massively better than that of the biplanes it replaced, but it packed a punch in the form of a gun turret mounted behind the pilot. The gunner could turn his turret to face any direction and pour a devastating fire from four 0.303in machine guns into enemy bombers. The Defiant was due to enter service in late 1939.

More impressive was the Hawker Hurricane equipped with no less than eight 0.303in machine guns that were mounted in the wings to fire forward. The aircraft was surprisingly nimble given its high speed and yet proved to be a stable platform when the eight machine guns were fired.

The Hurricane was due to start arriving with the RAF in December 1937, and the first order was for 600 aircraft, soon to be massively increased as the prospect of war approached. The swift delivery and large numbers were made possible by the fact that although the Hurricane was of revolutionary design, its construction was traditional. Much of the fuselage was covered in stretched fabric and the internal engineering was straightforward.

Rather different was the Supermarine Spitfire. Like the Hurricane, the Spitfire had eight machine guns mounted in the wings and was a low-wing monoplane — but there the similarities ended. The Spitfire was a highly sophisticated aircraft with an all metal cantilevered frame and pre-stressed metal skin. The internal mechanics were likewise of latest design to enable them to be squeezed into the highly aerodynamic shape and thin, elliptical wings that were to make this such a distinctive aircraft.

The advanced nature of the Spitfire’s design and construction meant that it was more expensive to both build and maintain than was the Hurricane, and that manufacturing was a more prolonged business. As a result the RAF ordered only 310 Spitfires for delivery June 1938, though again larger orders were soon made .

Dowding was understandably concerned that Germany was likewise developing more modern and sophisticated types of fighter. They certainly had the technical know how to produce aircraft that might prove to be every bit as good as the three British fighters.

In 1934 the Messerschmitt company of Bavaria had produced the Messerschmitt Bf108 “Taifun” (Typhoon). This was a light transport aircraft that could carry either three passengers or up to half a ton of freight. Most of its sales were to businessmen and rich individuals who used it as a touring aircraft by removing two of the seats and using the space created to carry luggage. The top speed of 190mph and ceiling of 20,000 feet were not terribly impressive, but the design was. The Bf108 was a low wing monoplane with an all metal construction and an air-cooled inverted V8 engine. The design and construction techniques could be easily adapted to produce a fighter.

On 1 August 1936, just days after becoming head of Fighter Command, Dowding received an urgent telephone call from the British Embassy in Germany. The excited diplomat on other end of the line explained that the opening ceremony of the Games in Berlin had featured a spectacular flypast by a new type of German fighter aircraft. It had been fast, agile and had displayed a phenomenal rate of climb. It was billed as the new Messerschmitt Bf109. Dowding set his intelligence officers to produce a report on the new aircraft.

When the report arrived a few days later, Dowding was not so alarmed as he had been at first. The Bf109 had a top speed of 292mph, a ceiling of 27,500 feet and a range of 405 miles. What really set Dowding’s mind at rest, however, was the armament. The Bf109 had only two 7.9mm machine guns mounted in the nose. As a vehicle to attack incoming bombers, the Bf109 was good enough, but when faced by the Hurricane or Spitfire it would be outclassed. Even so, it was a sign of things to come.

It was to be a busy month for those in Fighter Command watching German aircraft designs. In August 1936 the He51 went into combat for the first time. Several of these fighters had been sent by Hitler to take part in the Spanish Civil War on the side of the Nationalists, led by General Francisco Franco. The biplane quickly achieved air superiority as it shot down opponents with ease. That prompted Soviet dictator Josef Stalin to send some Polikarpov I15 biplane fighters to aid the Republican side. In response Hitler sent a few Messerschmitt Bf109 fighters, which then turned the tables once again. The triumph of the Bf109, however, was not complete. The fighter may have been better than anything else in Spain, but its armament of twin machine guns was too light to be truly effective. Many Republican pilots came safely home despite a close encounter with a Bf109.

Also fighting in Spain with German pilots was another modern fighter, the Heinkel He112. This agile fighter was very slightly faster than the Bf109, but had a slightly lower ceiling. The armament was the same for both.

Although neither Dowding nor any one else outside the higher echelons of the German air industry knew it at the time, the reason the Bf109 and not the He112 won the contract to supply the Luftwaffe was the Spitfire. As the officials of the German air ministry — the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (RLM) — were putting the He112 and Bf109 through their paces the prototype He112 crashed. Heinkel said it would be several weeks before a new prototype was ready. Meanwhile, German intelligence reported to the RLM that the RAF had placed orders for 300 Spitfires. Goering and his head of aircraft development Ernst Udet held a hurried conference. They decided that they could not wait for Heinkel to produce another prototype. Since the Bf109 had been marginally ahead in most of the tests, the RLM gave the contract to Messerschmitt.

The Luftwaffe bought a dozen or so of the He112 to use as testbeds for experimental radio equipment, engine variants, weapons systems and the like. In 1937 Heinkel was given permission by Ernst Udet to sell the He112 on the international arms market. It was typical of Udet’s rather informal way of doing business that he popped down to the Heinkel factory for the day to give Heinkel the news himself rather than send a formal ministry letter. According to Heinkel, Udet told him “Flog your crate off on the Turks or the Japs or the Rumanians. They'll lap it up.”

With his usual flair for publicity, Heinkel arranged for the He112 to be the surprise guest star at a number of air shows all over Europe, then invited well known fighter pilots from a number of different countries to come to Rostock to try the machine for themselves. The effort paid off handsomely. The Japanese placed an order for 72 fighters, followed by Austria which wanted 42, the Spanish who bought 18, the Yugoslavs who ordered 30 and the Hungarians who ordered 36 and began talks on a deal to allow them to manufacture more He112 fighters in Hungarian factories under licence. The final foreign country to order the He112 was Romania, which bought 30. In the event not all these orders would be fulfilled as they were incomplete when the war broke out.

The sales drive had given Germany’s potential enemies the opportunity to study the He112. The reports that came back to Dowding at Bentley Priory confirmed him in his views of German fighter design. The Germans were producing aircraft that were good, but not that good. The He112 was fast, nimble and had a good ceiling, but it was not as fast as the Hurricane or the Spitfire that would soon be serving with the RAF. Crucially they were comparatively poorly armed. While both the Spitfire and Hurricane had eight machine guns, the He112 had only two.

Meanwhile, rumours had been circulating in aircraft circles that the Heinkel company was working on something very special. The Heinkel works at Rostock where new designs were produced and prototypes tried out were famously secretive and well guarded. The owner, Ernst Heinkel, had been one of Germany’s foremost aircraft designers since 1914. He had gained a reputation for keeping his designs under wraps until the last minute. Even major potential customers such as Udet’s RLM had no idea what Heinkel was up to until he presented them with a prototype.

In 1931 Heinkel had hired two young and highly talented aircraft designers: the twins Walter and Siegfried Gunter. The Gunters had then disappeared into the Heinkel design shop to work amid conditions of almost pathological secrecy. By late 1937, it was rumoured that they were working on something top secret. The news that something was going on seems to have leaked out of the RLM where officials were reported by various agents and air news reporters to be referring to a “Projekt 1035” that was said to be concerned with high speed.

At this time Heinkel’s company was undergoing a massive expansion programme as the company geared up for the mass production of the aircraft types that it had sold successfully to the Luftwaffe. These included not only the bomber He111, but also the twin-engined seaplane the He115. There was also the long range bomber, the He177 Grief (Griffin) which was just starting to be designed at this date.

One of the men who picked up the rumours of something happening at the Heinkel works was Major Arthur W. Vanaman, the Assistant Air Attache at the US Embassy in Berlin. Vanaman’s duties included building relationships with both German aircraft manufacturers and potential buyers of US aircraft. While he was no spy, he was expected to keep a note of all he saw and to pay particular interest to any military gossip, information or aircraft that came his way. The German government was, of course, fully aware of Vanaman’s duties so they kept a close eye on him while allowing him to go about freely. After all, at this date, the USA was not considered to be a potential enemy of Germany but to be a future neutral nation that it would pay to remain on good terms with. The Germans talked more freely in front of Vanaman than they did in front of French, British, Polish or Czech diplomats.

Vanaman’s reports back to Washington first mention something special in the military department at the Heinkel works in the spring of 1938. He had heard of a project called the He100 that included a revolutionary evaporative cooling system for the engine. He asked Heinkel if he could go to the Rostock factory for a visit, but was told he could not and was invited to the Oranienburg factory instead — where the Heinkel 111 bomber was being produced. Vanaman was not particularly surprised by the rebuff, after all Ernst Heinkel was notoriously secretive, but it did increase his suspicions that something new was being developed at Rostock.

With his background in air engineering, Vanaman thought he knew what the new style cooling system was. The American aircraft manufacturer Curtiss had tried to make a new form of engine cooling work, but had failed to produce a practical device and had given up. Up to this date, all air engines were either air-cooled or water-cooled. In an air-cooled engine the engine was equipped with large flanges that were exposed to the air stream. The heat from the engine was dissipated through the flanges into the air. Large engines produced too much heat for this system to work and instead had water tubes running through and over the engine. The water was pumped away to a radiator that was placed in the air stream and so got rid of the heat — the same system is used in modern cars. Both systems meant that considerable air drag was set up by the flanges or radiator, thus slowing the aircraft.

The evaporative system did not produce drag, and so would lead to a higher air speed. As the hot water was pumped away from the engine block a small proportion of it was diverted into a large chamber where it was allowed to expand into steam. The steam chamber was then cooled, making the steam condense back into water to be pumped back to the engine block. In an aircraft the condensing chamber would be a wide, flat panel set into the fuselage or wing where the slipstream would cool it effectively. The rapid expansion into steam, followed by condensation was a very effective cooling system, but it called for the water to be pumped around the system under high pressure and for the condensing chamber to be under low pressure. It was this that had defeated Curtiss, but which Heinkel was said to have solved.

Vanaman was convinced that if Heinkel had solved the engineering problems of evaporative cooling he could, and almost certainly was, using it to produce a high speed fighter. Vanaman reported his conclusions back to Washington, but still lacked any firm evidence.

One of the reasons that Hitler had been elected to office was his ambition to annex to Germany all areas where the majority of the population was German-speaking. “Ein Volk, Ein Reich” (One People, One Country) was the slogan on the lips of the German government. German-speaking Austria had already been swallowed. In March 1938 the German armed forces had rolled over the Austrian border unopposed and a plebiscite held on 10 April produced a massive majority of Austrians voting to join Germany.

That left the German-speaking Sudetenland in western Czechoslovakia and the Danzig Corridor in western Poland. Neither Czechoslovakia nor Poland would want to hand over their lands to Germany, but neither were they militarily strong enough to stand up to Germany alone. Hitler knew that both states were in talks with Britain and France to try to secure alliances against Germany. In the event France, but not Britain, signed an alliance with the eastern states.

It thus became imperative to Hitler to convince France that the costs of war with Germany would be prohibitive. Josef Goebbels and his propaganda machine was put into action. Thus it was that the old German air ace from the First World War, Ernst Udet, extended an invitation to an old French air ace to visit him in Berlin. The French air ace in question was Joseph Vuillemin, by this date the Chief of Staff of the French Air Force. Udet was known for his energetic social life, and Goering for his boisterous sense of humour. Both men turned on the charm for Vuillemin.

Having been wined and dined, Vuillemin was taken on a tour of air-related sites. These included Luftwaffe bases, at one of which the entire German fleet of bombers was parked about as if they were usually based there. Next day Vuillemin was taken to a different base where all the same bombers were again on display, but as if they belonged to units based at this different airfield. Goering jovially announced that these were the two biggest bomber bases and asked if Vuillemin wanted to see some of the smaller ones. Vuillemin declined.

Then it was off to the Messerschmitt works in Bavaria for more fine dining, and a tour of the factory. Vuillemin was allowed to view a Messerschmitt BF109 at close quarters, even getting into the cockpit and being allowed to poke about as much as he liked. The fighter, Vuillemin noted, seemed to be identical to those that had fought in the Spanish Civil War having two machine guns.

Finally, there was a visit to Rostock and the Heinkel factory. Vuillemin was escorted around by Ernst Heinkel and Ernst Udet. Again he was allowed to inspect one of the German fighters, this time the He112 that was being sold on the export market. As the tour was coming to an end, the party happened to stroll past a Fieseler Fi156 Storch, a light transport aircraft able to carry four passengers. Udet casually suggested that he take Vuillemin up to have a look at the Heinkel works from the air, and take in the historic town of Rostock as well. Vuillemin agreed.

The pleasure flight passed off happily enough until Udet was coming in to land back at the Heinkel works. From out of nowhere a sleek fighter painted in Luftwaffe squadron markings roared down as if attacking the Storch. It swooped past at incredible speed, passing less than 30 feet from the cockpit of the Storch. Vuillemin leapt out of his skin, but Udet managed to keep the Storch under control. He put the transport down, helping the badly shaken Vuillemin down to the ground as the fighter came in to land. Vuillemin watched the fighter, realising that it was a totally new type of aircraft that he had never seen before. It was not a Bf109, nor was it a He112. Ernst Heinkel and members of his team came bustling up and hurriedly led Vuillemin away from the runway and out of sight of the fighter. Vuillemin got the impression that he had not been meant to see it.

Back in Berlin, one of Vuillemin’s party walked into a room where Udet was having a conversation with Erhard Milch, then Goering’s deputy at the Luftwaffe. The two men had their backs to the door and did not seem to have heard the Frenchman enter.

“What did old man Heinkel say about the production of those new fighters?” asked Milch.

“Not bad,” replied Udet. “The second production line is almost ready to start, but the third production line will not be ready for a few weeks yet.” At that point the two Germans noticed the Frenchman and hurriedly changed the subject.

Vuillemin went back to Paris a thoroughly depressed man. He sat down and wrote a report about his visit concluding that the Luftwaffe had a massive bomber force and that a new, superlative fighter was in production at Heinkel that was much better than the Messerschmitt Bf109. He concluded that if it came to a straight war between France and Germany, the French Air Force would not last 14 days. More likely it would be wiped out in 10 days.

Vuillemin’s report had the results that Hitler had intended. When in September, Hitler demanded that Czechoslovakia hand over the Sudetenland, the Czechs turned to their ally France. But France called in Britain and Italy for talks with Hitler in Munich. The result was that the four big powers ordered Czechoslovakia to hand over the Sudetenland at once. Hitler had got what he wanted by frightening France out of a war. Poland would be next.

However, the Vuillemin tour had an unforseen result. The French government now believed that they could not defeat Germany alone, but needed allies. The British government of Neville Chamberlain concluded from the events of 1938 that Hitler had to be stopped, and that only force would do so. They quickly joined France in an alliance with Poland. If Germany attacked Poland to annex the German-speaking areas, Britain and France warned Hitler, it would mean war. Hitler did not believe them. The conclusions he drew from 1938 were that France would not fight at all and Britain would not fight alone.

The French reports about Vuillemin’s visit were passed on to Dowding and RAF Fighter Command. Details were lacking, but what there was confirmed what Dowding already knew. The close view of the Bf109 and He112 gained by Vuillemin confirmed to Dowding that the aircraft being flown by the Luftwaffe were slower and less well armed than the Spitfire and Hurricane that by this date were starting to enter service with the RAF.

The new Heinkel fighter was another problem entirely. If Vuillemin were to be believed, the new fighter was very fast indeed. Vanaman’s reports about a new cooling system reinforced the view that Heinkel was going for speed in his design. There was no news from either Vuillemin or Vanaman about the armament of the new fighter. However, if speed was a paramount feature, as it seemed to be, then it was unlikely that Heinkel would encumber his fighter with extra weaponry. It seemed that the Germans were content with two machine guns on the Bf109 and on the He112. The new fighter would probably be no different.

On 16 September 1938, Vanaman took up his invitation to visit the Heinkel factory at Oranienburg. The visit went well and conversations covered the sort of topics to be expected when technically-minded airmen got together. At one point, as the tour group was strolling across the tarmac, Vanaman spotted a small aircraft behind a building. He tried to avoid paying too much obvious attention to it, while at the same time finding an excuse to stop the walk so that he could snatch surreptitious glances at the aircraft.

As soon as Vanaman got back to his office, he sat down to sketch the aircraft and write a hurried report. Although the aircraft had not been in Luftwaffe markings, Vanaman concluded that it was a fighter. Its overall size and shape would not allow it to be anything else. There were two features that stood out. First the aircraft did not have the elliptical wings of the He112 and was therefore a new type. Second there were no air intakes for the radiators — so Heinkel must have produced a working evaporative cooling system. Vanaman concluded that the elusive Projekt 1035 and He100 were one and the same: Heinkel was producing a new, very fast fighter to take over from the Bf109 at some unknown date in the future.

Later Vanaman heard from a source he does not name in the report he hurriedly submitted that Heinkel was proving to be a pest to Udet’s RLM. Heinkel had produced about a hundred airframes for a new type of aircraft and was making all sorts of unreasonable demands of the RLM. He wanted a series of new engines produced with all sorts of odd modifications for him to test in the new aircraft. And he wanted the loan of Luftwaffe pilots to do the testing, and he wanted high tech equipment, the details of which changed almost daily.

Vanaman rushed off a second report. He concluded that Heinkel was in the final stages of producing a fighter that was at the very cutting edge of German air technology. If the RLM had paid for about a hundred pre-production variants, as it apparently had, and was funding Heinkel’s demands then it was almost certain that the Luftwaffe was not only very impressed by Heinkel’s work but had decided to buy the new fighter in large numbers. Vanaman thought a final version might be ready for rigorous testing by the spring of 1939.

Dowding soon got to see Vanaman’s work and added it to his own growing files on the new fighter.

Then, in April 1939, came a fresh burst of information about the mysterious new aircraft being produced by Heinkel. The German government announced that a new Heinkel sports aircraft had broken the world speed record. Observers from the Federation Aeronautique Internationale (FAI) confirmed the fact and produced both data and photos from the flight which had taken place at the Heinkel works at Oranienburg on 30 March. The aircraft had averaged 746.606kph (463.64 mph) over four measured runs. Heinkel announced that the record breaking aircraft was a specially adapted version of the He112 fighter. He called it the He112U.

Dowding’s intelligence team quickly snapped up copies of the photos released by the FAI, but they did not learn much. The photos of the aircraft in flight showed a small object going very fast and were blurred. The photos of the aircraft on the ground all showed the pilot, Hans Dieterle, and the team from Heinkel standing in front of the aircraft in such a way as to block all details of the wings and tail.

A week or so later Goebbel’s propaganda ministry released a news movie about the flight. It did not take Dowding’s team long to spot something odd about the movie. The aircraft shown in the movie was not the same as that in the FAI photos. The FAI photos showed an aircraft that was of unpainted, polished metal with putty used to fill in gaps between metal plates and smooth over rivet heads and other bulges — all well known techniques to reduce air resistance and increase speed. The aircraft in the movie newsreels was painted with Nazi symbols and had no putty.

Clearly the German propaganda ministry was up to something, but what?

The aircraft in the movie was quite obviously not an He112. It had relatively straight wings, while He112 had clearly bent elliptical wings. The movie aircraft had a long thin nose, the He112 had a shorter, thicker one. Some intelligence officers suggested to Dowding that the aircraft in the movie was the new and mysterious Heinkel fighter. Perhaps Goebbels was trying to fool potential enemies into thinking that the new fighter was faster than it really was by pretending that it had broken the world speed record. On the other hand, the new fighter was supposedly a closely guarded secret, so why would the Germans parade it around on a newsreel movie? Perhaps the aircraft in the RAI photos was the real mystery fighter that had really broken the world speed record, while the aircraft in the movie was some completely different aircraft put forward so that the world would not know what the real fighter actually looked like.

It was a puzzle that Dowding could not solve.

In March 1939 Czechoslovakia was dismembered. The Sudetenland had already been taken by Germany the previous autumn. Now the Slovak-speaking half of the country declared itself to be independent, while German troops marched into the Czech half to establish what they termed the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, but was in reality little more than a slave province for Germany. Czech farmers were thrown off their land to make way for German farmers, Czech government officials were sacked and all aspects of government taken over by Germans. Thousands of people deemed by the Gestapo to be troublemakers were rounded up and thrown into prison camps.

In April 1939 Hitler announced that the German-Polish Non-Aggression Pact of 1934 was no longer in force. At the same time he opened talks with Britain, France, Italy and Russia aimed at solving what he termed “The Polish Problem”. He stated that he wanted those parts of Poland that had been taken from Germany at the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 to be returned to Germany. However, the fate of Czechoslovakia after the Sudetenland had been handed over did not bode well for those parts of Poland left over. Poland refused to hand over the disputed areas. Britain and France backed Poland and Mussolini’s Italy refused to take sides. The Soviet Union, however, was willing to help and secretly agreed to support Hitler if they were allowed to annex eastern provinces of Poland.

On 1 September 1939, Hitler attacked Poland without warning, claiming that the Poles had infringed the German border. Two days later Britain and France declared war on Germany. Suddenly all of Dowding’s preparations had to be put into practice for real. It was with renewed interest that he read the intelligence reports coming back from Poland on how the Luftwaffe was performing.

They made for grim reading.

The Poles had suspected that the German attack would come without warning and that Polish air bases would be among the first targets to be bombed. They had therefore moved most of their aircraft off the peacetime air bases to specially constructed temporary airfields where men and munitions were kept in tents and sheds hidden under trees. Thus when the Luftwaffe flattened the Polish air bases on the morning of 1 September they were bombing mostly empty buildings and hangars.

From their hidden bases the Polish pilots went up to do battle. The PZL 37 Los proved to be a fine bomber, carrying a heavy load while being fast and nimble in combat. The fighters were less impressive. The PZL P11 had been among the best in the world when it appeared in 1931, but was by 1939 obsolete. The PZL P24 was considerably better, but was available only in small numbers. In any case the Polish air force was heavily outnumbered having about 400 front line aircraft to face the 1,600 fielded by the Luftwaffe over Poland. In terms of aircraft shot down, the Poles did not do badly downing some 280 German aircraft while losing about 330 of their own. But the Germans had more to lose.

The Polish Air Force collapsed by 14 September by which time all their temporary bases had been overrun by the rapidly advancing German panzers and the few Polish aircraft left intact had nowhere from which to operate. The rapid German advance was due to the new tactic of “blitzkrieg” (lightning war). This consisted of fast-moving columns of tanks and armoured cars which smashed holes in the enemy front line, then penetrated deeply before fanning out to attack supply lines, communication links and reinforcements. This left the enemy front lines short on food and ammunition and cut off from orders, making them easy for the more slowly advancing German infantry and artillery to defeat. The role of the Luftwaffe was to co-operate closely with the army. In particular the Stuka dive bombers were to respond to radio appeals from the fast moving panzers to attack enemy strongpoints, artillery or tanks. On 17 September, the Soviet Union invaded Poland to take the eastern provinces and on 27 September Poland surrendered.

Large numbers of Polish pilots and crew fled via Romania to France and Britain. They were intensively questioned about German aircraft before being formed into squadrons to serve with the French and British air forces.

The Polish pilots reported meeting two distinct types of German fighter in combat. There was a larger, twin-engined fighter with a crew of two which had forward-firing and rearward-firing guns: the Messerschmitt Bf110. The second type was a single-engined type with forward firing guns: the Messerschmitt BF109.

If Dowding could content himself that the mysterious Heinkel fighter was not yet in service, he was shocked to read of the awesome firepower of the Messerschmitts and of the unprecedented speed of the Bf109. The Poles were estimating speeds for the Bf109 of around 340mph, some 50mph faster than had been reported in Spain and faster than the British Hurricane. The Bf110 was estimated to be just as fast, but less nimble in combat.

Just as disconcerting for Dowding were the reports of battle damage inflicted by the Messerschmitts. Unlike the aircraft attacked by Bf109s in Spain, those who met them in Poland rarely escaped once they were in the sights of the German pilots. Even a short burst of gunfire resulted in Polish aircraft falling apart, catching fire or exploding. Clearly the Germans had uprated the weaponry on the Bf109 and done so with spectacular results. However, the Poles never managed to shoot down a Bf109 over Polish-held territory so nobody was able to report on what that weaponry was.

However, a Bf109 was shot down at Rimling on the Western Front by a French pilot. The German aircraft came down relatively intact, and French intelligence experts were soon pulling it to pieces. They found that the Bf109 now had a Daimler-Benz DB601A engine, replacing the Jumo 210D of the models that had flown in Spain. That explained the increased speed of the fighter. The downed aircraft retained the twin 7.9mm machine guns in the engine cowling, but now had two additional machine guns mounted in the wings. This did not fully explain the heavy battle damage reported by the Poles. Some experts thought that perhaps the Poles had exaggerated damage in the heat of battle, others worried that some Bf109s had a heavier armament still.

Dowding had to face the possibility that the Germans had mastered the production and use of the airborne cannon. The mounting of 20mm cannon in fighters had been considered by the RAF in the mid-1930s, but had been discounted. Although firing a large shell that exploded on contact with an enemy aircraft was clearly much more effective than machine gun bullets, there were drawbacks.

First the greatly increased weight of the cannon made the fighter slower. Second the cannon fired more slowly than a machine gun so that a pilot had to be able to shoot much more accurately to be sure of hitting an enemy than if using machine guns. Thirdly, firing a cannon at high muzzle-velocity produced such recoil that the fighter firing the weapon could be pushed off course, and in the longer run shaken to pieces. The RAF had tried reducing the muzzle velocity to cut recoil, but that only reduced the range and accuracy of the cannon and made it effectively useless in air to air combat.

If the Germans had found a way to mount a cannon on a fighter without inhibiting the fighter’s performance than they would be a step ahead of the Hurricane, and probably on a par with the Spitfire. There was, as yet, no firm proof that the Germans had managed this, but it is clear from his correspondence that Dowding was worried by the possibility.

The conquest of Poland was followed by what was to become known as the Phoney War. Neither the British nor the French wanted to launch a land invasion head on into the heavily fortified German border, nor were they willing to breach Belgian neutrality by going around the edge of the German fortifications. It was widely anticipated that the Germans would break Belgian neutrality and the Allies opened talks with the Belgian government over how to deal with that eventuality when it occurred. Meanwhile, the Allied armies settled down to wait.

In the air, more was possible. The RAF was keen to start bombing military targets in Germany, but the French objected. Vuillemin was convinced that the Germans had a vastly superior bomber force to that of the Allies. He thought that any bomber attack on Germany that resulted in civilian casualties would lead to massive reprisals on French cities by the Luftwaffe, and he felt that the French fighters would be almost powerless to stop them. He persuaded the French government to insist that the RAF attack only targets where civilian casualties were absolutely impossible. That ruled out any barracks or ammunition dumps in or near towns, so the RAF was restricted to bombing enemy warships at sea. The RAF did undertake long missions by bombers over Germany although all that was dropped were leaflets. These missions did, however, allow the RAF to test navigation techniques and to identify targets for future bombing attention.

At dawn on 9 April 1940 a force of Messerschmitt Bf110 fighters attacked the Danish air force on the ground and wiped it out. A thousand German soldiers came ashore from a German freighter in Copenhagen harbour and attacked various key targets in the city. The Royal Guard drove off the attack on the Royal Palace, but other places were captured. At 8.30am Denmark surrendered.

On the same day, Germany invaded Norway from the sea and from the air. The Norwegian air force consisted of 12 Gloster Gladiator fighters plus a large number of long range reconnaissance aircraft that could also carry bombs for use against ships. Seven of the Gladiators were destroyed on the ground, but the other five got into the air and claimed four German bombers before they themselves were shot down by Bf109 fighters. The Norwegian government ordered the long range reconnaissance bombers to fly to Britain, later to be followed by the Norwegian navy, merchant ships and as many men of the army as could be got out in time. The forces left in Norway surrendered on 10 June, but King Haakon VII refused to surrender to Germany and continued the war from Britain.

A few British Hurricanes had been used during the later stages of the fighting in Norway. The combat reports sent back to Dowding indicated that the Hurricanes had performed well against the Bf110 twin engined fighters, but less well against the Bf109. From what his pilots told their debriefing officers, Dowding concluded that the heavier Bf110 fighters were definitely equipped with cannon. Whether or not the Bf109 also had cannon was more of an open question, but the evidence was beginning to indicate that they did.

Dowding was just beginning to digest this news and assess what it meant for his fighters when shocking news arrived. The German air magazine, Der Adler (The Eagle) had published a special edition on the Norwegian campaign. On the front cover was a dramatic artwork described as showing “An Air Battle over Norway”. The British bomber being shot down was easily recognisable as a Handley Page Hampden. The German fighter was described as being the new Heinkel He113 Super Jaegar (Super Fighter).

The Germans were fielding a new model of fighter that surpassed the existing fighters in every respect. Dowding’s nightmare had come true.

The intelligence that had been coming out of Germany meant that the Der Adler article did not come as a huge shock, though some of its contents did. The article inside the magazine was entitled “Heinkel Fighters on Watch in the North” and was lavishly illustrated with photos of the Super Fighter in flight and on the ground. Most of the text and captions was the sort of gushingly enthusiastic propaganda that might be expected. “No sooner are the Super Fighters in the air than they are ready to confront any intruders,” ran one typical caption.

There were, however, two facts that were of great interest to the RAF intelligence officers. The text stated that the new fighter “held the absolute air speed record for Germany one year ago.” It had been in April 1939 that the world speed record had been broken by what was then described as a “sports aircraft” made by Heinkel. Quickly comparing the new He113 Super Fighter with the pictures of the supposed sports aircraft showed that the two were remarkably similar — almost identical in fact.

Of course, nobody believed that the He113 Super Fighter had itself taken the world speed record. The record-breaking aircraft would have been stripped of weapons, armour and all surplus weight. Nevertheless, the new fighter was obviously designed for high speed.

Just as disconcerting for the RAF was a photo that showed the He113 head on while parked on the ground. The caption read “This is the portrait of the He113 which is seen by those pilots whose routes take them in the path of the German Luftwaffe.” The view showed the apertures for three weapons: a cannon in the nose and two heavy machine guns in the wings. It was a formidable array of weaponry that easily outclassed the eight light machine guns carried by the Spitfire and Hurricane. Dowding and his team had a lot to think about.

One photo showed a mechanic working on the engine of the aircraft. Just enough detail was visible to reveal that the He113 was powered by the Damler-Benz DB601 aircraft engine. This was a liquid-cooled, inverted V12, 33.9 litre, fuel-injected piston engine. It could deliver 1050hp for long periods, with a peak output of 1,159hp for short periods. This was not a new engine for although it had entered service only in 1935, it was based on the DB600 which was some years older. It was generally considered to be a good, efficient and reliable engine, but nothing particularly remarkable.

In the weeks that followed, Der Adler printed other stories about the He113 Super Fighter, as did other newspapers and magazines. The stories were picked up by the press in neutral countries, who were helpfully supplied with photos of the aircraft by the Germans. Very soon a night fighter version was announced. Photos that were reproduced were shown with the markings of at least 10 different Luftwaffe squadrons — the nightfighters had a crescent moon logo on the engine cowling. Another squadron had a marking that showed a dagger thrust through an admiral’s cocked hat. Presumably it was a naval version or a version specialised for maritime work in some way.

All the prewar reports of Heinkel working on a top secret, highly effective fighter aircraft to replace the Messerschmitt Bf109 had been vindicated. Dowding ordered his intelligence men to prepare an immediate assessment of the He113 Super Jaegar based on what the Germans had announced themselves and what could be gleaned from prewar reports.

The intelligence analysis landed on Dowding’s desk on 20 May 1940. The speed with which the report was compiled shows the seriousness with which Dowding and the RAF treated the subject. . The report was classified as being Top Secret and was guardedly marked on the inside cover as being “based on information received to date”. The report was circulated to all the senior officers in RAF Fighter Command, each of whom signed the front cover to show that they had seen it, wrote comments where they felt necessary and then passed it on. The annotated copy came back to Dowding on 30 May.

The report emphasised that so far little was known for certain about the He113, but went on to give the up to date information about the aircraft so far as it was known.

First, the He113 was very fast. It was estimated to have a top speed of 390mph, faster than the Spitfire’s 355mph. Rate of climb was thought to be 2,600 feet per minute, a bit slower than the Spitfire’s 2,857 feet per minutes. However, the fuel-injected DB601A would give the He113 an advantage in diving over the Spitfire with its carburettered Rolls Royce Merlin engine. The armament could be deduced from the head-on photo in Der Adler. The RAF report stated that the apertures had been measured and found to be larger than those needed for standard Luftwaffe 7.9mm machine guns. The report concluded that the aircraft probably had three 20mm cannon — an awesome amount of firepower that would easily outclass anything the RAF had in service.

However, Air Vice Marshal Robert Saundby, who saw the report on behalf of RAF Bomber Command, spotted a problem with this conclusion. The wings of the He113 were too thin to hold the ammunition drum that fed the 20mm FF cannon that was used by the Luftwaffe. “This aircraft may carry 3 cannon,” Saundby concluded in his note, “but they are not mounted in this photograph.”

Other data could also be deduced from the Der Adler photos since they included tools and other objects of known size. The He113 could be deduced to be 26 feet 11 inches long, have a wingspan of 30 feet 10 inches and a height when parked on the ground of 8 feet 2 inches. The wing area was estimated to be 156 square feet. This made it rather smaller than the Spitfire or the Hurricane.

The configuration of the wings was something new. The outline of the wings was slightly swept forward, though this impression was given more by the forward bend to the trailing edge than to the forward edge, which actually bent back slightly. The wings were slightly gulled, meaning that they bent upward half way along so that the tips were above the roots. Opinion was divided about the purpose of this wing shape. It might have been designed to allow for a better airflow over the wing from a large propeller, but on balance it was thought that it was probably an adaptation to improve performance at high altitudes.

The retractable undercarriage folded inwards, which was unusual in German aircraft. The result of this was two fold. First the wheels were wider apart on the ground and second the mechanics for lifting them was located further out in the wings than in most models. It was thought that this was done to allow more space for the guns in what looked to be rather thin wings.

Dowding’s report also included a copy of Vanaman’s report on the new fighter, though most of the information he supplied had been incorporated into the RAF report. There were also cuttings from magazines and newspapers published in Italy and in neutral countries such as Hungary and Romania.

The secret report attempted to analyse how many of the He113 were in operation and how quickly they were being produced. Reports coming out of occupied Poland indicated that the PZL factory had been taken over by the Germans for the production of a secret aircraft. If this factory was being used to produce the He113, it was estimated, then about 30 aircraft a month could be produced without undue problems. More could be produced if Heinkel scaled back production of his bombers and seaplanes in his factory in Germany.

The German magazine article in Der Adler had stated that one squadron of He113 Super Fighters had been used in Norway. The other squadrons, the article did not say how many, were reported to be stationed along the north German coast to intercept any Allied bombers attempting to come in off the North Sea to attack targets in Germany.

This made sense. Presumably a squadron of experienced fighter pilots had been sent to Norway to put the new fighter through its paces in combat. Once that had been done, the fighter was being held back to a quiet sector where the new pilots could get used to their new aircraft steadily and without undue pressure. Just as important, so long as the He113 Super Fighter was active only over Germany there was no chance that one would be shot down or suffer engine failure over Allied territory and therefore be available to Allied intelligence.

Dowding and his intelligence team tried to guess the current state of the German supply of this terrible new weapon. The He113 Super Fighter was clearly the same aircraft that had given Vuillemin such a scare on his visit to Rostock in August 1938 and that had been glimpsed by Vanaman a few weeks later. A tentative time line was reconstructed that had the German RLM asking German aircraft manufacturers to design a replacement for the Bf109 as that aircraft had gone into service in 1936. It would be reasonable for Heinkel to have produced a number of prototypes for testing by the summer of 1938.

It was believed, therefore, that Vanaman had been correct when he reported that about 100 pre-production examples were in existence in the autumn of 1938. The conversation between Udet and Milch about production lines that had been overheard by Vuillemin’s assistant was believed to have referred to another aircraft, presumably the He112 which was then being sold for export. If so, then Udet and the RLM would probably have chosen their preferred configuration of engine and weaponry for the He113 Super Fighter in the spring of 1939. Given the time necessary to get a new production line established, flight test the new aircraft, deliver them to the Luftwaffe and then train the pilots on how to get the best out of the new model, it would be reasonable to expect the first squadron to enter service about a year after the aircraft was ordered.

That would be in the spring of 1940. Right on cue, the first squadron had seen service in Norway in April 1940. Exactly how quickly other squadrons would enter active service was open to question. It depended on how many resources the German government was willing to devote to manufacturing the new aircraft and how many experienced men the Luftwaffe would take out of the front line to train the new pilots. It might take months for the new aircraft to enter service in large numbers, or several squadrons might already be ready.

The RAF and French Air Force briefed their pilots on the new He113 Super Fighter. They were told of its capabilities and shown photos and artworks so that they were able to recognise it when they saw it. Then the air staffs got on with their plans for the coming campaign and waited for the He113 Super Fighter to appear in combat.

A public announcement of the new fighter was made at the same time. It was assumed that word would leak out from the air force personnel sooner or later, and it was better for the RAF to control the flow of information. The information released to the public was more limited than that in Dowding’s report, and some key facts had been changed. The top speed of the He113 was deliberately reduced from an estimated 390mph to just 360mph so that it was close to that of the Spitfire.

Now Dowding and his pilots could do nothing except wait for the terrible new fighter to appear in action. It was just a question of time.

The long Norwegian campaign was still dragging on when the German attack in the West began. As long expected, the attack began with a German drive through Belgium to outflank the heavily defended Maginot Line that blocked a direct invasion over the Franco-German border. What was not expected was that Germany would also invade the Netherlands. As the German panzers, artillery and infantry advanced into Belgium and the Netherlands, the British army and much of the French army marched northeast to link up with the Belgian army and fight a decisive battle in central Belgium.

The air campaign began with massed German bombing attacks on airfields across northeastern France. In these attacks the French suffered heavily since they had allocated the permanent pre-war air bases to their own squadrons and given the British squadrons small, private airfields where the RAF men had been forced to spend the winter camped out in tents or in clubhouses. Hundreds of French aircraft were destroyed on the ground in the first two days, or rendered useless by the destruction of their repair and maintenance facilities. By comparison the RAF Hurricane squadrons got off lightly.

The French Air Force led by the defeatist Vuillemin had two types of modern monoplane fighter when the Germans struck. Of these, only 36 Dewoitine D520 aircraft were in service, and most of those were quickly destroyed. There were, however, more than 900 of the Morane-Saulnier MS406 fighters with front line squadrons. Most of these were stationed facing the German border or to protect major cities so few got into action in the early days of the German invasion. By the time France surrendered, 387 of these fighters had been destroyed by the Germans, with French pilots claiming 183 German aircraft shot down in return.

The bulk of the air fighting over northern France therefore fell on the British squadrons sent over to support the British army on the ground. The Fairey Battle light bombers proved to be outclassed and were shot down in large numbers. The Hurricanes did much better, but were massively outnumbered in the air and found their bases overrun. The Hurricane pilots again reported that they did well against German bombers and Bf110 fighters, but barely held their own against the Bf109.

It was now clear both from combat reports and from downed Bf109 fighters that fell behind Allied lines that the Germans had equipped the Bf109 with cannon. Most Bf109 had a 20mm cannon in each wing and twin machine guns mounted in the nose, a few had a third cannon firing through the centre of the propeller. It was a tremendous weapons array that outdid the British eight 0.303mm machine guns. There was still debate about how effective the slower firing cannon would be in combat compared to the faster machine guns, but nobody was in any doubt that in the hands of a skilled pilot the new Bf109E was a deadly machine.

There was, as yet, no sign of the He113 Super Fighter entering combat, which came as something of a relief to Dowding and the RAF.

On the ground the war went from bad to worse for the Allies. The German advance into Holland and Belgium had only been a feint. The main attack was delivered through the Ardennes Mountains. The massed panzer columns had easily broken through the weak French forces guarding what had been expected to be a quiet sector, and then had raced west to reach the sea at Abbeville. The entire British army and much of the French was cut off by the panzer advance and was falling back on to Dunkirk with its back to the sea.

The decision was taken to evacuate the British army and as many French soldiers as possible by sea from Dunkirk. Thus began the epic Dunkirk Evacuation which saw small pleasure boats and yachts picking men up from the beaches and taking them out to larger ships offshore which then carried the men back to Britain. All this time the Luftwaffe was bombing and strafing the ships, the small boats, the men on the beaches and the defenders holding off the panzers.

The task of the RAF was to bomb the German forces around Dunkirk and to protect the Allied forces in Dunkirk from German bombers. Dowding organised a rotating duty rota that saw squadrons of Hurricanes and Spitfires moved up to Manston, Biggin Hill and other Kent airfields for a few days to fly missions to Dunkirk, then pulled back to be replaced by fresh squadrons. The key problem was the distance that had to be flown to get to the battle area. The Hurricane, and even more so the Spitfire, had been designed as short range defensive weapons. By the time they had flown to Dunkirk, they had only enough fuel for a few minutes of fighting before they had to go home again. It was all too easy to miss an incoming German raid.

Then, on 29 May, Dowding’s worst fears were confirmed. A flight of Hurricanes from No.213 Squadron had been about to pounce on a force of German Heinkel 111 bombers when they were in turn bounced by German fighters diving steeply down from high overhead. The German fighters had been He113 Super Fighters. The Hurricane pilots had pulled off from the German bombers to meet the new threat. One pilot said he had got on the tail of an He113, fired a burst and seen smoke pouring from its engine, but none of his comrades had seen the incident so it was logged as an unconfirmed “damaged”.

The He113 was not seen again over Dunkirk. Perhaps, it had been an isolated foray by a squadron brought up from north Germany to join the battle. Nobody knew.

After the Dunkirk Evacuation, the German armed forces turned on the rest of France. Another devastating blitzkrieg followed and France surrendered on 22 June. Britain was alone.

Dowding now knew that the Luftwaffe was going to turn its might on Britain. It would not be doing so from Germany, from whence only long range bombers and Bf110 fighters could reach Britain, but from bases in newly occupied northern France. Britain now lay within easy reach of the Bf109 and the He113 Super Fighter.

Hitler made peace overtures to Britain, but they were ignored. The war would go on. Hitler decided to invade Britain in the autumn of 1940. If the German navy was to be able to transport the army over the Channel to Britain, it first needed to be safe from air attack. That meant the Luftwaffe had to have control of the air, and that in turn meant that Dowding’s RAF Fighter Command had to be destroyed.

The Battle of Britain that followed has often been portrayed in movies and books as a succession of heavy German attacks made by dozens of bombers protected by swarms of fighters. The raids being aimed at fighter bases, aircraft factories, radar sites and other targets. Such raids did take place, but the Battle of Britain was a much more subtle and deadly affair than that.

Goering could achieve that aim in two basic ways: by destroying all of Fighter Command’s bases or by destroying all of Fighter Command’s aircraft. He also knew by this date that the British had some sort of system for tracking aircraft by using radio waves. We know that system now as radar, but in the summer of 1940 it was something of a mystery to the Germans. Much of July was spent by the Luftwaffe flying lone aircraft or small groups toward the British coast and seeing how long it took the RAF to send up fighters to intercept. In this way the Luftwaffe was able to form a rough idea of how accurate British radar was and what its range from the British coast was. Armed with this information, Goering and his staff laid their plans for the Battle of Britain.

The destruction of Fighter Command on the ground would be carried out principally by bombing the fighter airfields, such as Manston, Biggin Hill, Tangmere, Gatwick, Croydon and Kenley, but aircraft factories, oil refineries and other targets would also be hit — so would the radar stations along the south coast of England. Goering and his planners knew that if they bombed only these targets it would make things easy for the RAF. Any formation of German bombers heading for eastern Kent, for instance, could only be heading for RAF Manston, and the British would be able to position their fighters accordingly. For this reason Goering insisted that bombing raids had also to be carried out on other useful targets, such as docks, railway junctions and army bases. That would keep the British guessing as to which target a formation was going to hit. To make things even more difficult for the British, the bombers were ordered to follow indirect routes to their target. A squadron of bombers would start off heading for RAF Manston, but at the last minute turn west and bomb the docks at Dover instead.

To destroy the RAF in the air, Goering resorted to tricks and strategems that he would have learnt in the First World War, and which his pilots assured him had still worked over Spain, Poland and Norway.

A small force of bombers would be sent to attack a minor target, accompanied by a small escort of fighters. The RAF controllers might decide to send up a similarly small force of Spitfires or Hurricanes to deal with the threat. But lurking 10,000 feet higher up Goering would have positioned a great swarm of fighters. Any British aircraft that tried to attack the small number of bombers would be bounced by the swarm from above, totally outnumbered and annihilated.

Another effective trick was for three or four fighters to peel off from a much larger formation then head for an RAF fighter base. The Germans would not attack the base, but would circle high above ready to pounce on any damaged British fighter that was limping back to base after combat with the main formation. Alternately a force of fighters would be sent on ahead of the main raid, timed to arrive over the RAF base just when the British aircraft were taking off and so were at their most vulnerable.

On other occasions, Goering would send over formations made up only of fighters, but flying in the type of formations favoured by bombers. The Germans realised early on that British radar could not distinguish between different types of aircraft, and so would mistake such forays for formations of bombers flying without fighter escort. The British fighters would race to attack the seemingly easy target, only to find themselves heavily outnumbered by German fighters.

Other fighter formations were sent over on what were known as “freie jagd” (free hunts), which were dubbed “free chasing” by the British. The formations were given a rough route to follow, but otherwise were given complete freedom to attack anything that they felt was worth the expense of a few bullets and cannon shells. Trains, lorries, bridges, marching men, factories, workshops and almost anything else could be targetted, along with any aircraft found in the air or on the ground. Such freie jagds proved to be enormously popular with Luftwaffe fighter pilots who relished the freedom given them. They were certainly preferable to flying close escort to bombers when they had to stay tied to the slower bombers.

Just to vary things a bit, some bombers did go over without fighter escort. And some small formations of bombers and fighters did attack minor targets without having a swarm of fighters flying high overhead. Anything to keep the RAF controllers and pilots guessing.

Another useful ruse was for the Germans to put up a formation of bombers and fighters and send it toward the English coast. The British radar would pick up the formation, and the controllers would naturally scramble the RAF fighters to go up and intercept the raid. As it neared the coast, however, the German formation would turn around and head back toward France. The British fighters would watch them go, then land to refuel. At this point a second German formation would appear and get to their target while the British fighters were still on the ground — more than once the target proved to be those very fighters.

Goering and his planners also sought to tire out the RAF pilots, wear them down and exhaust them so that they made mistakes in combat. Every day, German formations would take off, get close enough to Britain to be picked up on radar so that the RAF fighters would be scrambled, and then turn back to France.

Small formations of fighters would be sent across the Channel at very low level to slip under the radar cover. They would tear across the English countryside, arrive over a fighter base before they had been detected and spray the area liberally with machine gun bullets and cannon fire. Such raids were not intended to do any serious damage, but to deprive the British of sleep, rest and relaxation. Nobody could truly rest if at any moment they would have to run for shelter to avoid a cascade of bullets. The author’s father was serving with the RAF at this time and was slightly wounded in exactly one of these raids carried out by three Messerschmitt Bf110 fighters on his base at lunchtime.

This deadly game of trick, ruse and ambush began in late July as the Luftwaffe began to assault the British defences. It was not long before the He113 Super Fighter was back in action. Flight Lieutenant James Davies of 79 Squadron was one of the first to report an encounter with an He113. He was sent up with his squadron to attack a German formation coming in off the English Channel. Davies’s flight was detached to deal with the escorting fighters, a dozen or so Bf109s. Davies got into a dog fight with one Bf109 which dived down in an effort to escape. Davies went down after it, but suddenly realised that he had German fighters on his tail.

Abandoning his would-be prey, Davies flipped his Hurricane about and engaged those chasing him, which he now saw to be a flight of six He113 Super Fighters. With his first burst of fire, Davies struck the lead He113 head on and saw it explode in a sheet of flames. He then ran out of ammunition and had to flee the combat. The remaining He113 Super Fighters gave chase, pursuing Davies all the way back to his base at RAF Hawkinge where they peeled off rather than face the anti aircraft guns of the base. Davies landed with his Hurricane peppered with holes and counted himself lucky to still be alive.

On 9 August newspapers reported that the previous day an unidentified squadron of Hurricanes had been scrambled to intercept an incoming raid of German aircraft flying very high at about 30,000 feet. As the Hurricanes clawed up into the blue skies over Sussex they spotted a formation of twin-engined machines heading toward Eastbourne. As the Hurricanes got closer, the formation was revealed to be 36 Messerschmitt Bf110’s. Above and behind the Bf110’s were a smaller number of single engined fighters, identified as He113’s. It was a trap. The Hurricanes bore off, whereupon the Germans dived away toward France. The ruse had not only been a trap, but a decoy. As the Hurricanes landed to refuel another German formation attacked a shipping convoy off the Isle of Wight.

The Battle of Britain was now really gathering pace as Goering sought to destroy the RAF in two weeks of furious acton, starting on 13 August — a date he dubbed Adler Tag (Eagle Day). Vast formations of German bombers and fighters came over in seemingly endless waves.

On 14 August No.43 Squadron was sent up to engage enemy aircraft heading for Folkestone from France. The combat report that appeared in the press three days later had the names of pilots censored out. It read “Squadron engaged enemy aircraft over Folkestone at 12.31 hours. Pilot Officer A leader of Red Section attacked formation of 30 Ju87 (Stuka dive bombers). Fired at one which went down in flames. Fired at one Ju87 which went down in flames. Attacked a Ju87 which broke away. Blue Section engaged fighter escort. Sergeant B fired at Messerschmitt 109 and saw bullets going in and clouds of smoke pouring from enemy aircraft as it dived into cloud. Sergeant C attacked one of two Messerschmitt 109’s, fired a long burst and enemy aircraft disappeared into cloud emitting smoke. Sergeant D of Green Section got separated from the squadron, fired at a Messerschmitt 110 over Channel, saw enemy aircraft turn on its back and go down smoking. Sergeant D was then attacked by four He113’s and was forced down into field with failed engine and badly wounded left arm. Sergeant D was taken to hospital where he filed combat report and claimed one Heinkel He113 destroyed.”

Because nobody else had seen the He113 go down and no wreck was found, the RAF intelligence officers assumed that either it had limped back to France or had crashed into the Channel. The wounded Sergeant D was awarded a “probable” rather than a “kill”.

On 18 August the He113 Super Fighter appeared in a new role. At 3.30pm a flight of 12 He113 Super Fighters came roaring off the sea at Pegwell Bay in Kent and seconds later were tearing across RAF Manston at heights estimated to be under 20 feet from the ground. They opened fire with machine guns and cannons indiscriminately. Having raced across the airfield, the He113 Super Fighters disappeared back to sea before any retaliatory action could be taken.

The attack had been quick, unexpected and deadly. In all one Hurricane and seven Spitfires had been destroyed. One mechanic had been killed and 15 more injured. Numerous buildings had been riddled with holes, letting in rain and wind where they were least wanted. By itself the attack had not been particularly damaging, but it served to remind everyone that they could not relax for a single moment, keeping RAF personnel on edge and contributing to the tiredness that was beginning to be a real problem.

Reports of the He113 being seen in combat were now coming in thick and fast. Generally they were reported to be flying higher than other fighter escorts. Bf109 fighters might be seen accompanying bombers, or flying just above them, but the high escorts tasked with diving down on unsuspecting RAF fighters were often identified as He113 fighters. So were German fighters given specific tasks to do.

On 24 August the Boulton Paul Defiants of No.264 Squadron were at RAF Manston in Kent. They were ordered to conduct a series of standing patrols over the airfield to keep an eye open for any German fighters hanging about in the hope of downing a returning RAF fighter, or to tackle incoming bombers that evaded the radar system. At 8am it was the turn of the three Defiants of Yellow Section to go up. The aircraft piloted by Flight Lieutenant Campbell-Colquhoun and with Pilot Officer Robinson as gunner did not start first time, so it was a few minutes late getting into the air.

Eventually Campbell-Colquhoun got his Defiant airborne. Looking about he saw two fighters circling high above and, assuming them to be the other two Defiants of Yellow Section, he climbed up to join them. Campbell-Colquhoun manoeuvred his aircraft into his accustomed position just behind the leader. He settled down for a routine patrol when he happened to glance across at the fighter in position on the other side of the formation leader. He goggled in surprise and horror as he saw a huge black cross painted on the fuselage of the other aircraft. Glancing quickly ahead, Campbell-Colquhoun saw a black cross painted on the leader as well. Not only were they Germans, but Campbell-Colquhoun had little difficulty in identifying them as He113 Super Fighters.

Campbell-Colquhoun slammed the nose of his fighter forward into a dive, a sudden move that seems to have alerted the Germans to his presence. In a flash the German wingman was on the Defiant’s tail and was pouring gunfire into it. The first burst of German fire struck the Very light signals that all fighters carried for signalling, and they burst into life emitting huge quantities of smoke and flames. In his turret, Robinson had been taken by utter surprise first by his pilot’s sudden dive and abrupt evasion tactics, then by the stream of incoming fire. Now with smoke pouring out of the fuselage and unable to see a thing, Robinson concluded that the Defiant was going down in flames. He undid his harness, flipped open the door of the turret and began climbing out ready to parachute to safety.

At that point the Defiant returned to an even keel and the two He113 Super Fighters veered off as the rest of Yellow Section dived down to join the fight. Realising his aircraft was not crashing, Robinson clambered back into the turret, but by this point he had lost his intercom set and so was unable to talk to Campbell-Colquhoun. The pilot, for his part, assumed that Robinson had been killed by the German fire since he could not raise him on the intercom. Campbell-Colquhoun went down to land.

Just as he was putting the Defiant down on the grass, Campbell-Colquhoun realised why the German fighters had been over Manston. They had been sent on ahead to deal with any standing patrol of fighters and so clear the way for a force of bombers. The bombs started landing as the Defiant touched down. As soon as the aircraft stopped, Robinson and Campbell-Colquhoun leaped out and ran for cover, both equally amazed that the other was unhurt.

The rest of August passed in frantic haste as the incoming raids continued to appear in large numbers and with terrifying regularity. The Luftwaffe continued with its tricks and ambushes, with the He113 seemingly always on hand where it was least wanted. RAF pilots reported that whenever they were bounced from above or taken by surprise by fast-moving German fighters, it had usually been He113 Super Fighters that had been to blame. The Bf109 was deadly and an opponent to be feared, but it did not seem to be a patch on the He113.

It was not just RAF pilots who were producing useful information on the He113 and how it performed in battle. Luftwaffe pilots who had been shot down were questioned on the subject. Most of them refused to answer any questions at all, they had after all been trained in how to behave if captured. Only one pilot said anything during questioning, and that came as a surprise to the RAF interrogators. He said that he had been seconded to an He113 squadron for a couple of weeks and had hated it. The He113 was, he said, a pig to fly. Yes, it was fast and all that, but the controls were so complex it was all he could do to keep it in the air, never mind fight a battle. He had been glad to get back to his Bf109.

Other Luftwaffe pilots remained tight lipped during questioning, but the RAF had other techniques. The rooms in which prisoners were kept were bugged and their conversations recored. Other prisoners were put into rooms shared with German-speaking British men posing as Luftwaffe officers who tried to steer the conversation on to the He113. Through these means the RAF eavesdroppers picked up a lot of information. Although none of the downed Luftwaffe men were He113 pilots, they all knew about the Super Fighter and admired it enormously. The fighter was not, they said, present in large numbers as yet but production was on the increase and soon there would be hordes of Super Fighters smashing the RAF to pieces. In the mean time the handful of squadrons that were in the front line were showing the RAF what was in store.

It was a terrifying prospect for the RAF. But help was at hand from an unlikely quarter.

Unknown to Dowding and the British, a meeting took place in Berlin on 14 September between Hitler and his military chiefs. Goering was in France directing the assault of Britain, so the Luftwaffe was represented by his deputy Erhard Milch. Somewhat unexpectedly, Hitler suggested calling off the invasion of Britain altogether. He asked what the alternatives were to an invasion.

The navy chief, Admiral Erich Raeder, pointed out that Britain could be starved into surrender by a naval blockade. If he had the resources to build enough U-boats and fast battle cruisers, he said, he could disrupt the British convoy system and sink enough merchant ships to ensure that too few supplies got to Britain. It would, he thought, take about two years.

Milch put forward an alternative. He suggested that the Luftwaffe be used to bomb British cities to inflict massive civilian casualties, disrupt industrial output of war equipment and destroy the will of the British government to continue the war. Given the resources to build enough aircraft, Milch said, he thought the Luftwaffe could defeat Britain in less than half the time of Raeder’s plan.

Hitler said he would think about it.

On Tuesday 17 September the fighting opened soon after dawn with what radar reported to be a small formation approaching Dover at about 25,000 feet. A Spitfire squadron went up to meet it, and were warned as they climbed of a second German formation behind and above the first, at about 33,000 feet. The Spitfires attacked the lower formation, found to be 20 Messerschmitt Bf109s, but broke off the combat when the 15 He113’s that formed the higher formation dived down to join the fray.