Figure 4-1: Summa-rizing Cash Disburse-ment journal transac-tions so they can be posted to the General Ledger.

Chapter 4

The General Ledger: A One-Stop Summary of Your Business Transactions

In This Chapter

Understanding the value of the General Ledger

Understanding the value of the General Ledger

Developing ledger entries

Developing ledger entries

Posting entries to the ledger accounts

Posting entries to the ledger accounts

Adjusting ledger entries

Adjusting ledger entries

Creating ledgers in computerized accounting software

Creating ledgers in computerized accounting software

As a bookkeeper, you may be dreaming of having one source that you can turn to when you need to review all entries that impact your business’s accounts. (Okay, so maybe that’s not exactly what you’re dreaming about. Just work with me here.) The General Ledger is your dream come true. It’s where you find a summary of transactions and a record of the accounts that those transactions impact.

In this chapter, you discover the purpose of the General Ledger. I tell you how to not only develop entries for the Ledger but also enter (or post) them. In addition, I explain how you can change already-posted information or make corrections to entries in the Ledger and how this entire process is streamlined when you use a computerized accounting system.

The Eyes and Ears of a Business: Looking at the General Ledger

I’m not using eyes and ears literally here because, of course, the book known as the General Ledger isn’t alive, so it can’t see or hear. But wouldn’t it be nice if the ledger could just tell you all its secrets about what happens with your money? That would certainly make tracking down any bookkeeping problems or errors a lot easier.

Instead, the General Ledger serves as the figurative eyes and ears of bookkeepers and accountants who want to know what financial transactions have taken place historically in a business. By reading the General Ledger — not exactly interesting reading unless you love numbers — you can see, account by account, every transaction that has taken place in the business. (And to uncover more details about those transactions, you can turn to your business’s journals, where transactions are kept on a daily basis. See Chapter 5 for the lowdown on journals.)

The General Ledger is the granddaddy of your business. You can find all the transactions that ever occurred in the history of the business in the General Ledger account. It’s the one place you need to go to find transactions that impact Cash, Inventory, Accounts Receivable, Accounts Payable, and any other account included in your business’s Chart of Accounts. (See Chapter 3 for information about setting up the Chart of Accounts and the kind of transactions you can find in each.)

Developing Entries for the Ledger

Because your business’s transactions are first entered into journals, you develop many of the entries for the General Ledger based on information pulled from the appropriate journal. For example, cash receipts and the accounts that are impacted by those receipts are listed in the Cash Receipts journal. Cash disbursements and the accounts impacted by those disbursements are listed in the Cash Disbursements journal. The same is true for transactions found in the Sales journal, Purchases journal, General journal, and any other special journals you may be using in your business.

At the end of each month, you summarize each journal by adding up the columns and then use that summary to develop an entry for the General Ledger. Believe me, that takes a lot less time than entering every transaction in the General Ledger.

I introduce you to the process of entering transactions and summarizing journals in Chapter 5. Near the end of that chapter, I even summarize one journal and develop this entry for the General Ledger:

|

Account |

Debit |

Credit |

|

Cash |

$2,900 |

|

|

Accounts Receivable |

$500 |

|

|

Sales |

$900 |

|

|

Capital |

$1,500 |

In this entry, the Cash account is increased by $2,900 to show that cash was received. The Accounts Receivable account is decreased by $500 to show customers paid their bills, and the money is no longer due. The Sales account is increased by $900 because additional revenue was collected. The Capital account is increased by $1,500 because the owner put more cash into the business.

Figures 4-1 to 4-4 summarize the remaining journal pages that I prepare in Chapter 5. Reviewing those summaries, I developed the following entries for the General Ledger:

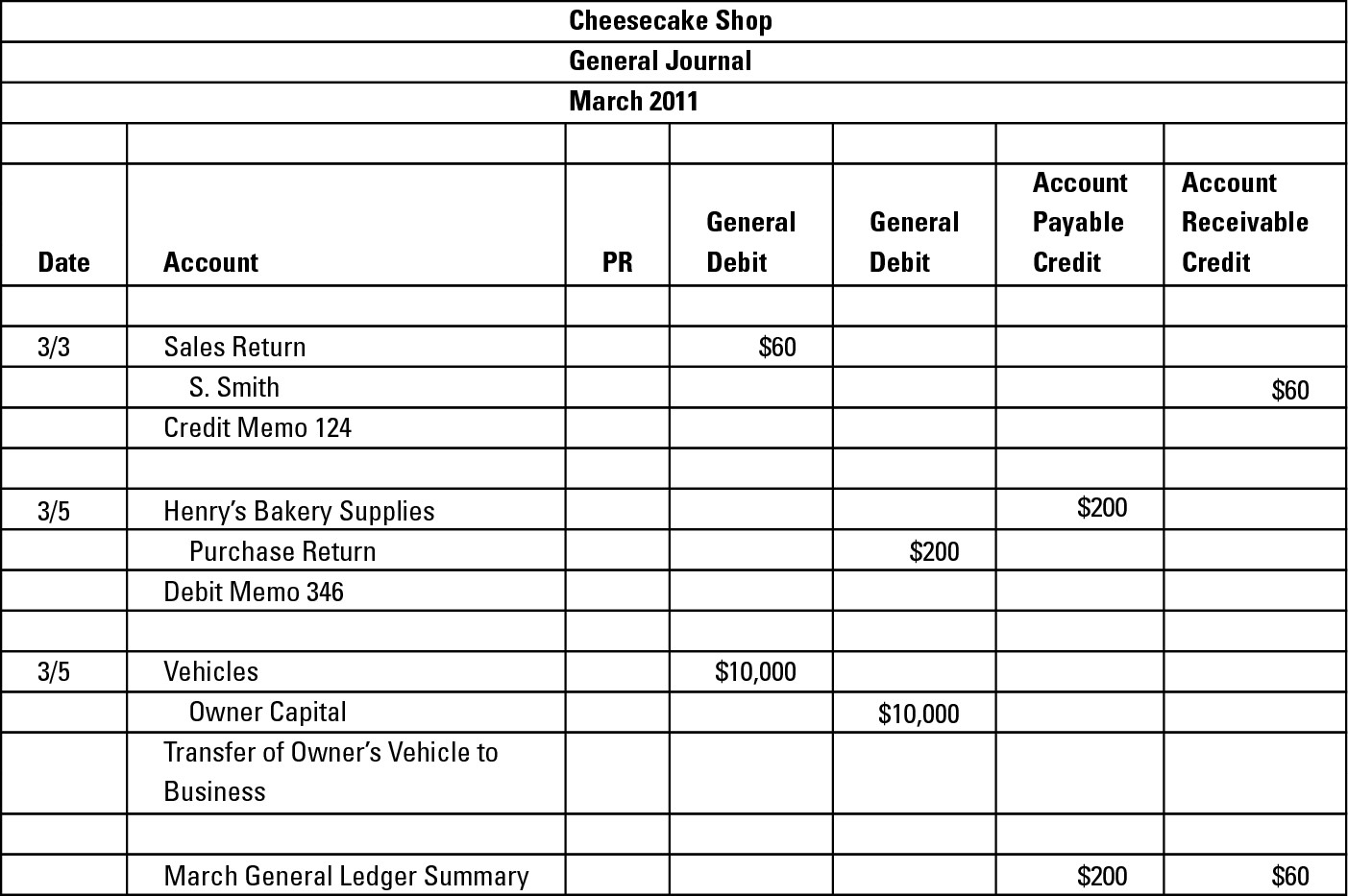

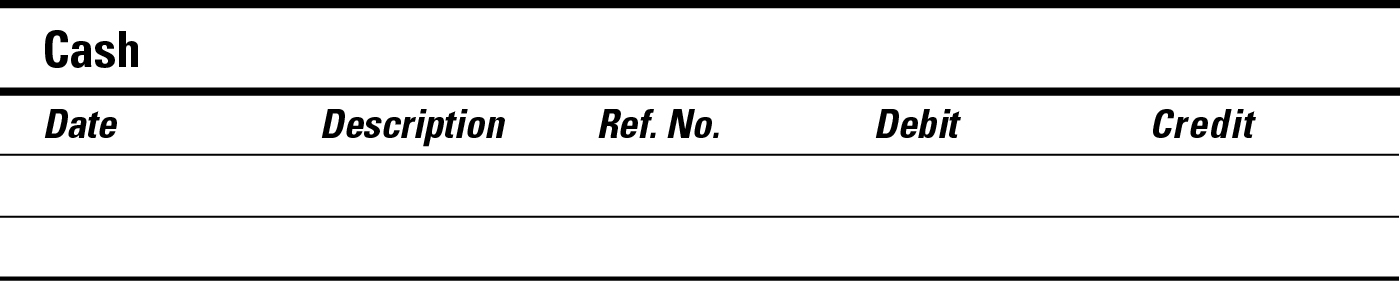

Figure 4-1 – Summarized Cash Disbursements Journal

Figure 4-2 – Summarized Sales Journal

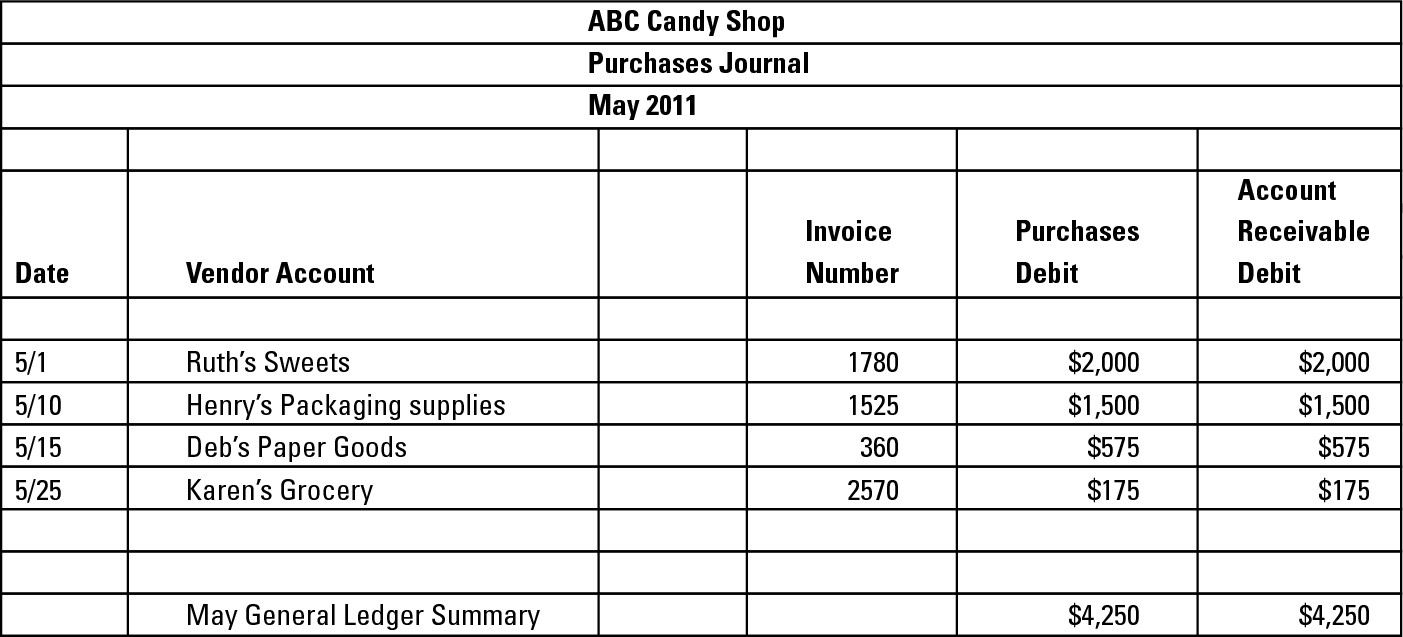

Figure 4-3 – Summarized Purchases Journal

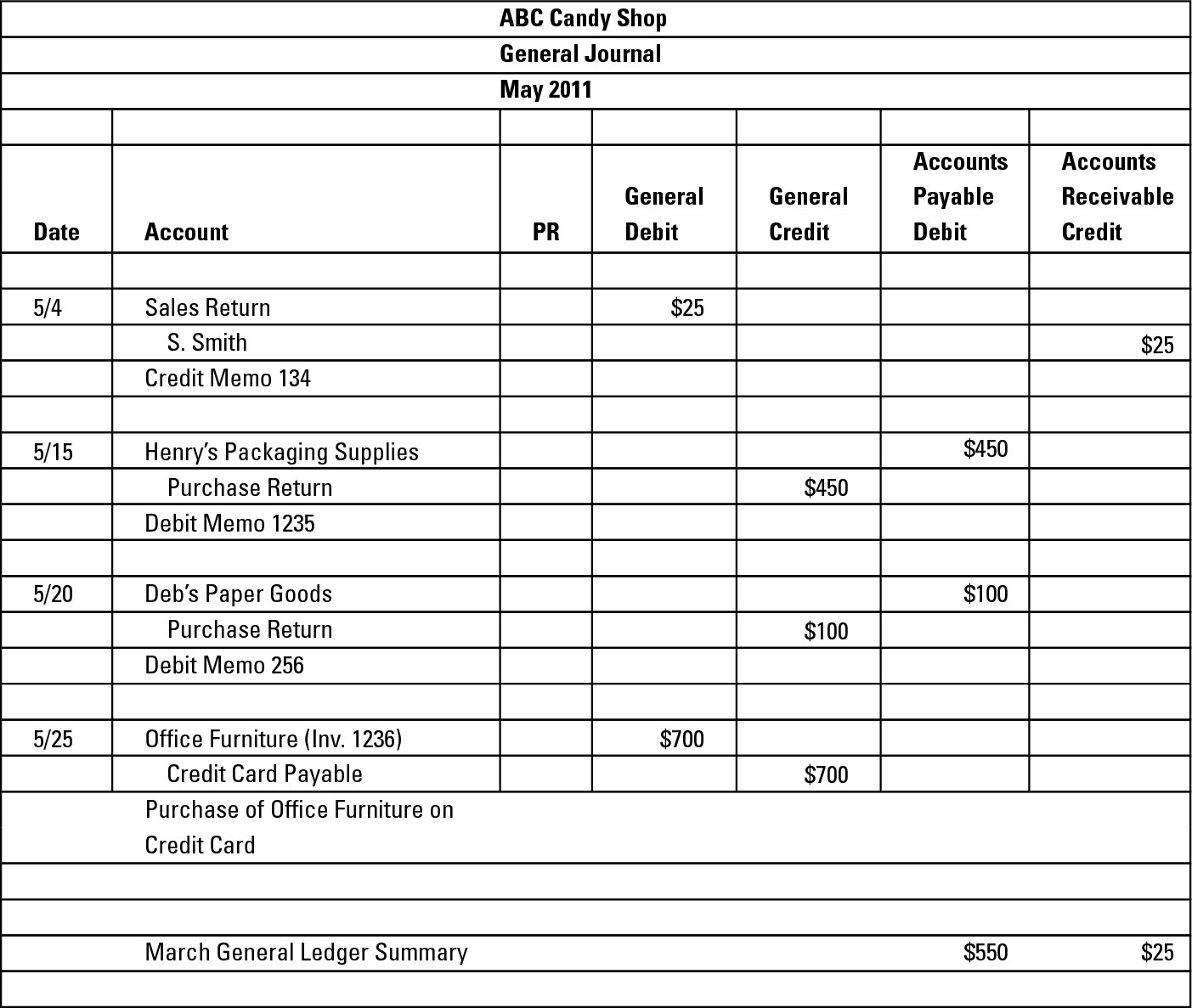

Figure 4-4 – Summarized General Journal

Figure 4-1 shows a summary of a business’s Cash Disbursements journal, which keeps track of all cash transactions involving cash sent out of the business.

The following General Ledger entry is based on the transactions that appear in Figure 4-1:

|

Account |

Debit |

Credit |

|

Rent |

$800 |

|

|

Accounts Payable |

$750 |

|

|

Salaries |

$350 |

|

|

Credit Card Payable |

$150 |

|

|

Cash |

$2,050 |

This General Ledger summary balances out at $2,050 each for the debits and credits. The Cash account is decreased to show the cash outlay, the Rent and Salaries expense accounts are increased to show the additional expenses, and the Accounts Payable and Credit Card Payable accounts are decreased to show that bills were paid and are no longer due.

Figure 4-2 shows the Sales journal, which keeps track of all sales transactions, for a sample business.

Figure 4-2: Summa-rizing Sales journal transac-tions so they can be posted to the General Ledger.

The following General Ledger entry is based on the transactions that appear in Figure 4-2:

|

Account |

Debit |

Credit |

|

Accounts Receivable |

$800 |

|

|

Sales |

$800 |

Note that this entry is balanced. The Accounts Receivable account is increased to show that customers owe the business money because they bought items on store credit. The Sales account is increased to show that even though no cash changed hands, the business in Figure 4-2 took in revenue. Cash will be collected when the customers pay their bills.

Figure 4-3 shows the business’s Purchases journal, which keeps track of all purchases of goods to be sold, for one month. The following General Ledger entry is based on the transactions that appear in Figure 4-3:

|

Account |

Debit |

Credit |

|

Purchases |

$925 |

|

|

Accounts Payable |

$925 |

Like the entry for the Sales account, this entry is balanced. The Accounts Payable account is increased to show that money is due to vendors, and the Purchases expense account is also increased to show that more supplies were purchased.

Figure 4-3: Summa-rizing Purchases journal transactions so they can be posted to the General Ledger.

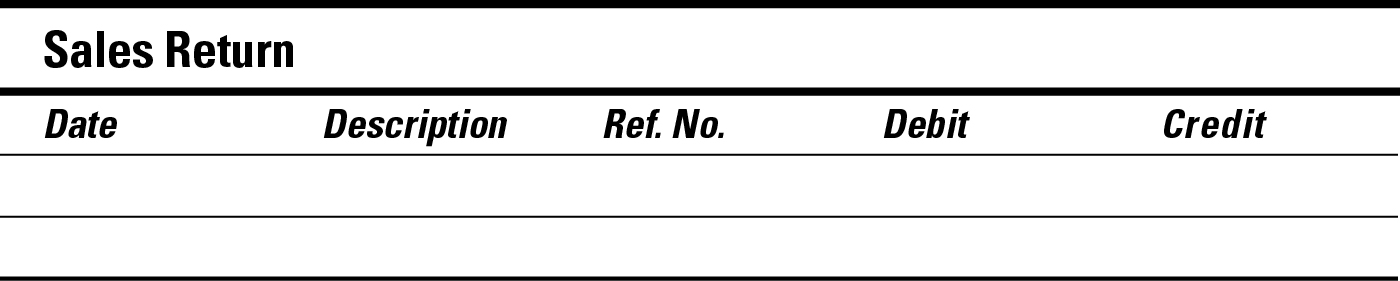

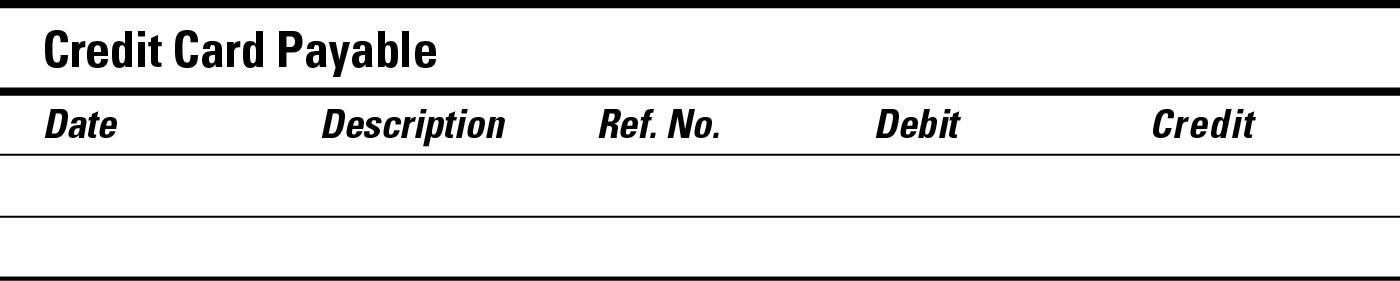

Figure 4-4 shows the General journal for a sample business. The General journal keeps track of all miscellaneous transactions that aren’t tracked in a specific journal, such as a Sales journal or a Purchases journal.

The following General Ledger entry is based on the transactions that appear in Figure 4-4:

|

Account |

Debit |

Credit |

|

Sales Return |

$60 |

|

|

Accounts Payable |

$200 |

|

|

Vehicles |

$10,000 |

|

|

Accounts Receivable |

$60 |

|

|

Purchase Return |

$200 |

|

|

Capital |

$10,000 |

Figure 4-4: Summa-rizing General journal transactions so they can be posted to the General Ledger.

In this entry, the Sales Return and Purchase Return accounts are increased to show additional returns. The Accounts Payable and Accounts Receivable accounts are both decreased to show that money is no longer owed. The Vehicles account is increased to show new company assets, and the Owner Capital account, which is where the owner’s deposits into the business are tracked, is increased accordingly.

Practice: Summaries for General Ledger

Q. Using the information in Figure 4-5, how do you develop an entry for the General Ledger to record information from the Purchases journal for the month of May?

A. Note that you only need to record the totals for the transactions that month in the General Ledger. You don’t have to record all the information.

|

Account |

Debit |

Credit |

|

Purchases |

$4,250 |

|

|

Accounts Payable |

$4,250 |

Figure 4-5: Sample page from a Purchases journal showing total purchases for the month of May for a fictitious company, ABC Candy Shop.

Solve It

1. Using the information in Figure 4-6, how do you develop an entry for the General Ledger to record transactions from the Sales journal for the month of May?

Figure 4-6: Sample page from a Sales journal showing total sales for the month of May for a fictitious company, ABC Candy Shop.

Solve It

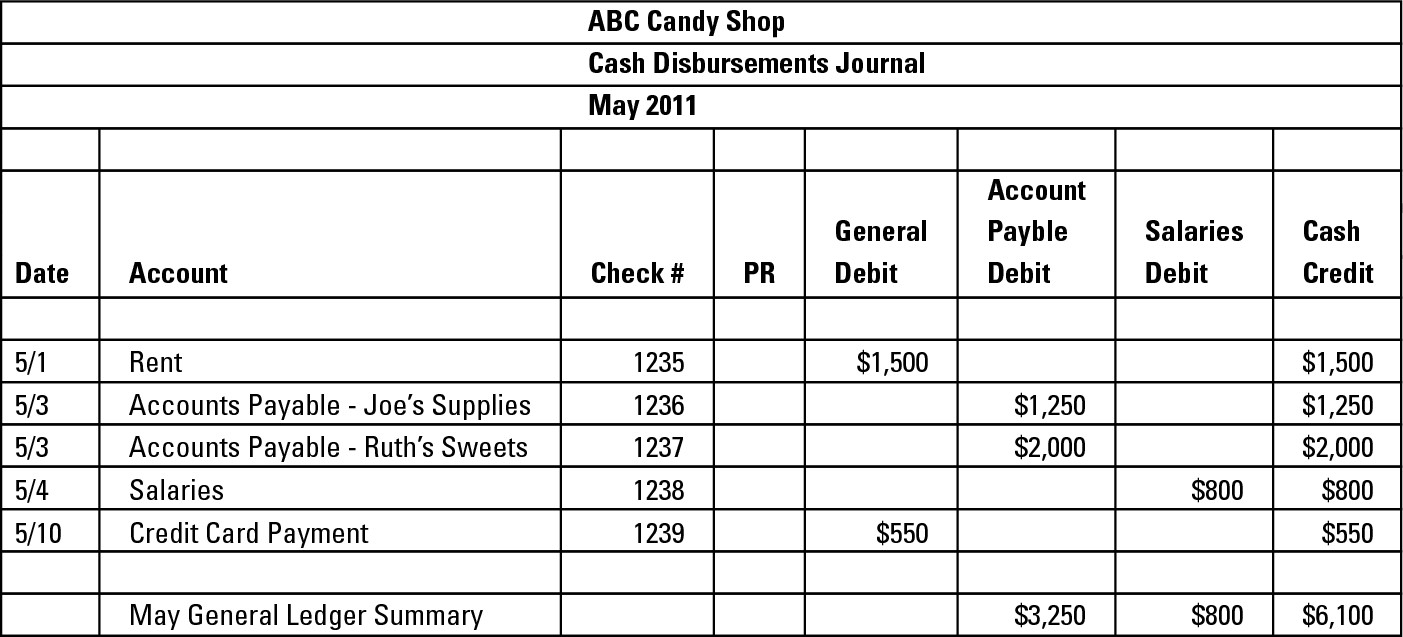

2. Using the information from Figure 4-7, how do you develop an entry for the General Ledger to record transactions from the Cash Disbursements journal for the month of May?

Figure 4-7: Sample page for a Cash Disburse-ments journal for the month of May for a fictitious company, ABC Candy Shop.

Solve It

3. Using the information from Figure 4-8, how do you develop an entry for the General Ledger to record transactions from the General journal for the month of May?

Figure 4-8: Sample page for a General journal for the month of May for a fictitious company, ABC Candy Shop.

Posting Entries to the Ledger

After you summarize your journals and develop all the entries you need for the General Ledger (see the previous section), you post your entries into the General Ledger accounts.

Whatever the reason someone is questioning an entry in the General Ledger, you definitely want to be able to find the point of original entry for every transaction in every account. Use the reference information that guides you to where the original detail about the transaction is located in the journals to answer any question that arises.

For the particular business in this section, three of the accounts — Cash, Accounts Receivable, and Accounts Payable — are carried over month to month, so each has an opening balance. Just to keep things simple, in this example, I start each account with a $2,000 balance. One of the accounts, Sales, is closed at the end of each accounting period, so it starts with a zero balance.

Most businesses close their books at the end of each month and do financial reports. Others close them at the end of a quarter or end of a year. (I talk more about which accounts are closed at the end of each accounting period and which accounts remain open, as well as why that is the case, in Chapter 22.) For the purposes of this example, I assume that this business closes its books monthly. And in the figures that follow, I give examples for only the first five days of the month to keep things simple.

As you review the figures for the various accounts in this example, notice that the balances of some accounts increase when a debit is recorded and decrease when a credit is recorded. Others increase when a credit is recorded and decrease when a debit is recorded. That’s the mystery of debits, credits, and double-entry accounting. For more, flip to Chapter 2.

The Cash account

The Cash account (see Figure 4-9) increases with debits and decreases with credits. Ideally, the Cash account always ends with a debit balance, which means there’s still money in the account. A credit balance in the cash account indicates that the business is overdrawn, and you know what that means — checks are returned for nonpayment.

Figure 4-9: Cash account in the General Ledger.

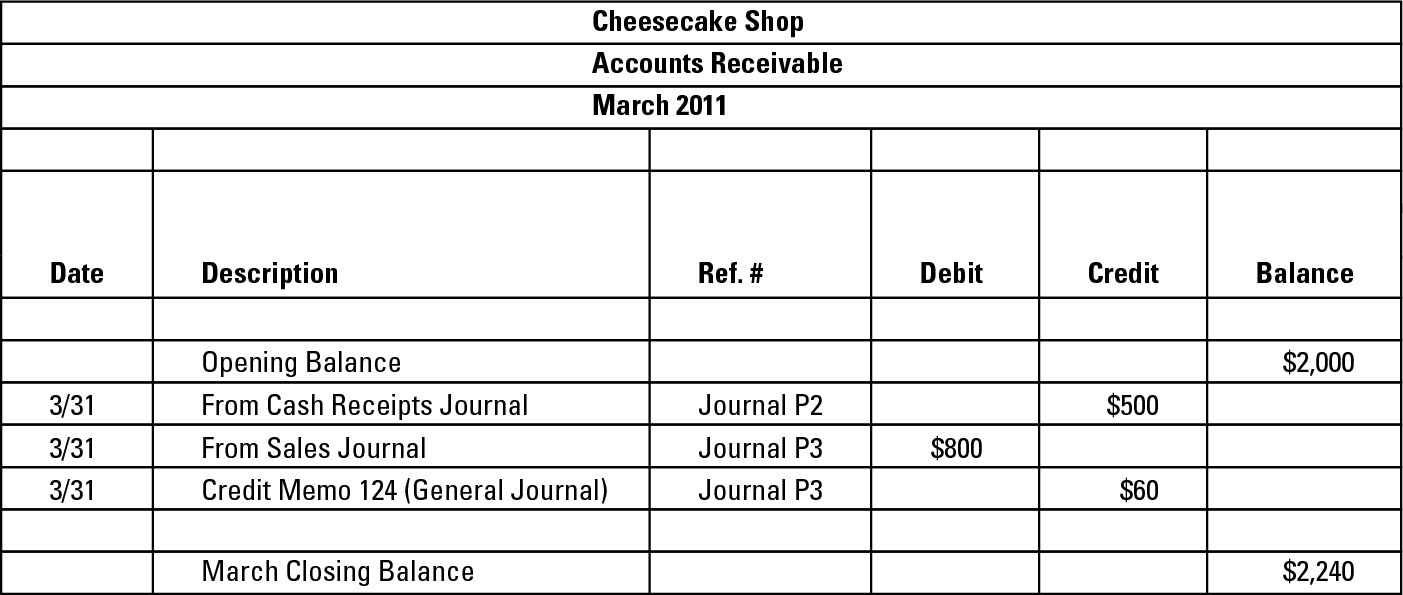

The Accounts Receivable account

The Accounts Receivable account (see Figure 4-10) increases with debits and decreases with credits. Ideally, this account also has a debit balance that indicates the amount still due from customer purchases. If no money is due from customers, the account balance is zero. A zero balance isn’t necessarily a bad thing if all customers have paid their bills. However, a zero balance may be a sign that your sales have slumped, which can be bad news.

Figure 4-10: Accounts Receivable account in the General Ledger.

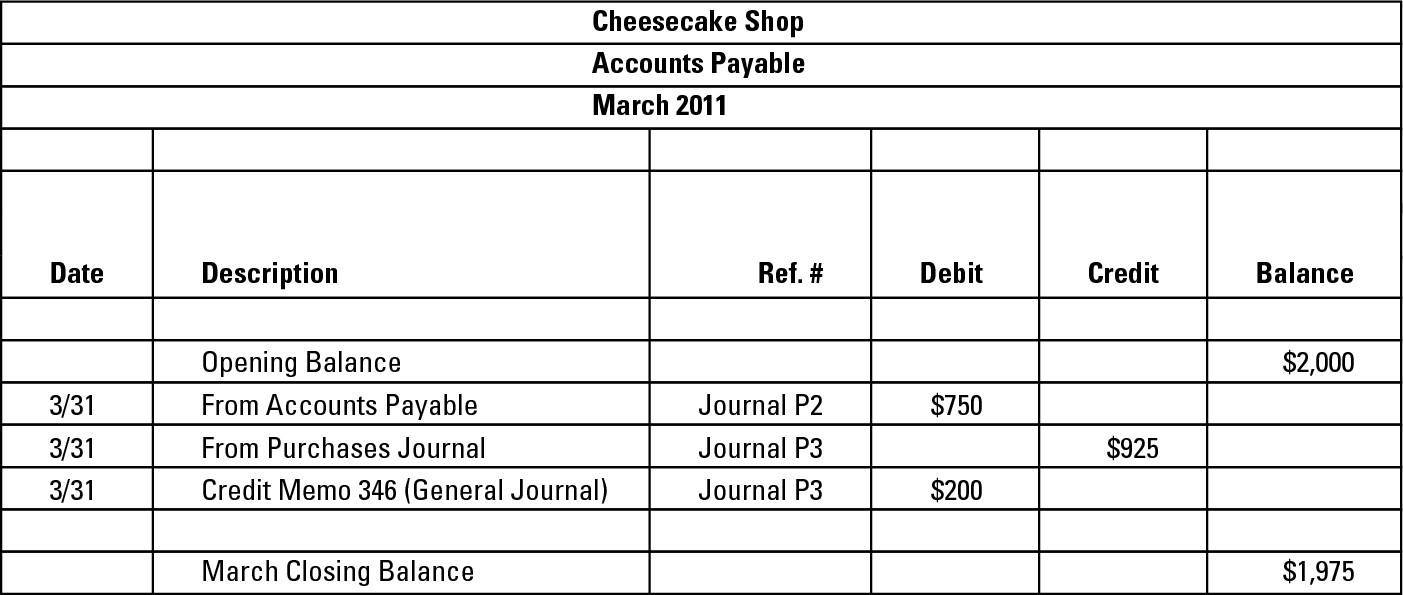

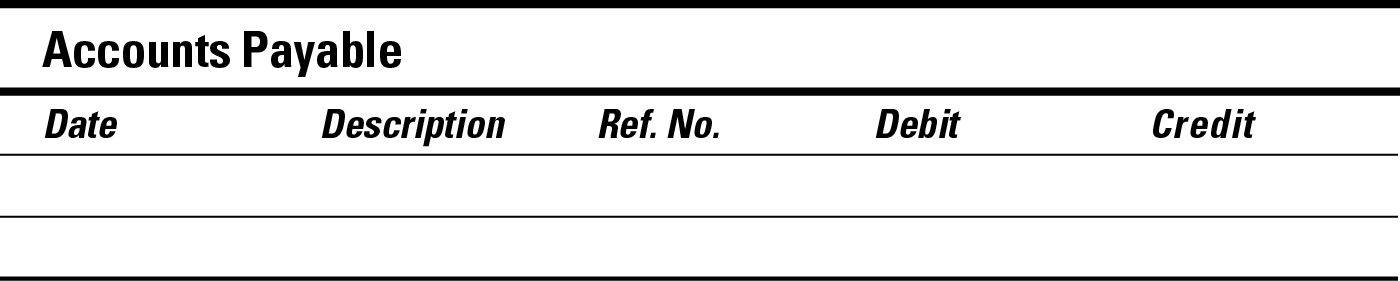

The Accounts Payable account

The Accounts Payable account (see Figure 4-11) increases with credits and decreases with debits. Ideally, this account has a credit balance because money is still due to vendors, contractors, and others. A zero balance here equals no outstanding bills.

Figure 4-11: Accounts Payable account in the General Ledger.

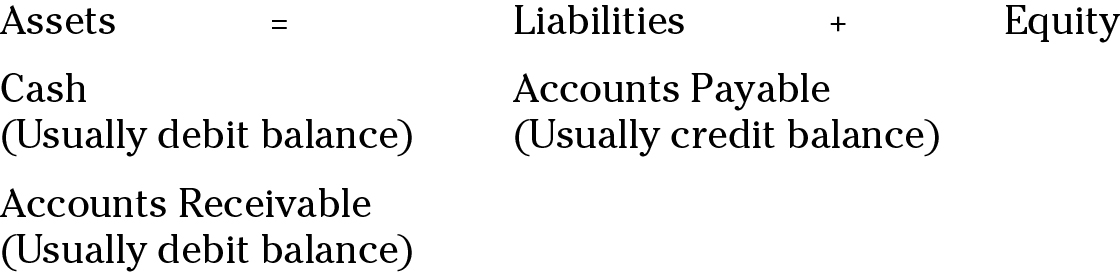

The balance sheet

These three accounts — Cash, Accounts Receivable, and Accounts Payable — are part of the balance sheet, which I explain fully in Chapter 18. Asset accounts on the balance sheet usually carry debit balances because they reflect assets (in this case, cash) owned by the business. Cash and Accounts Receivable are asset accounts. Liability and Equity accounts usually carry credit balances because Liability accounts show claims made by creditors (in other words, money owed by the company to financial institutions, vendors, or others), and Equity accounts show claims made by owners (in other words, how much money the owners have put into the business). Accounts Payable is a liability account.

Here’s how these accounts impact the balance of the company:

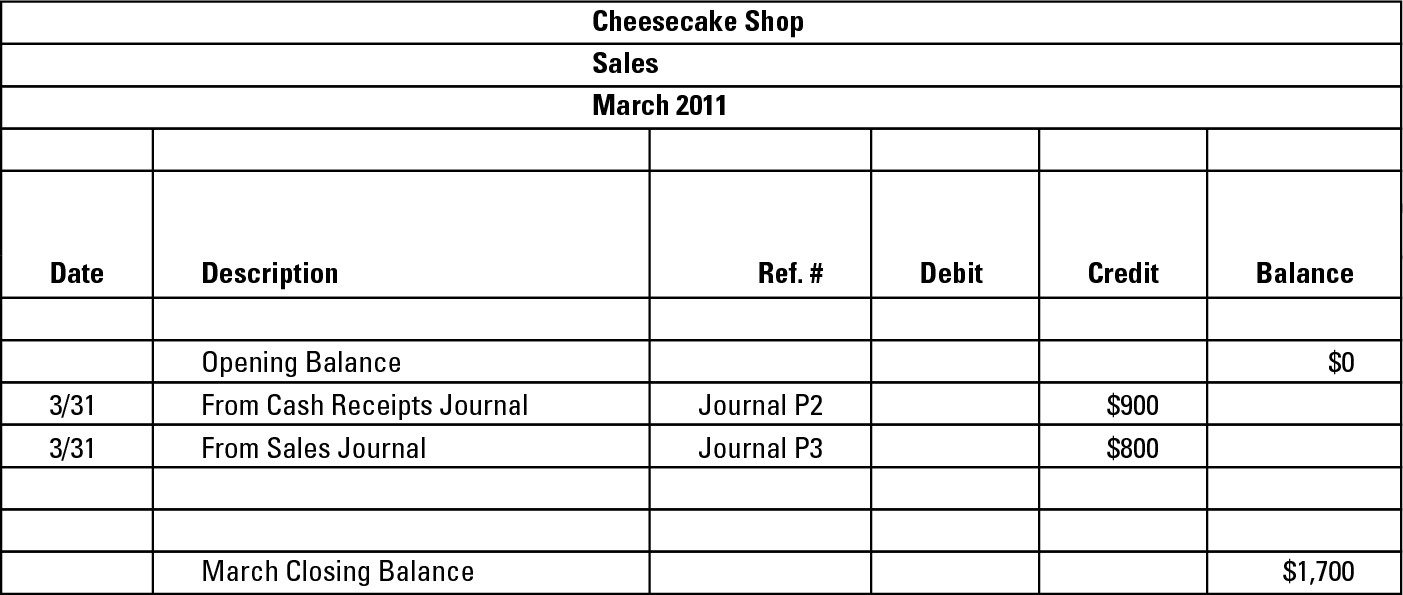

The Sales account

The Sales account (see Figure 4-12) isn’t a balance sheet account. Instead, it’s used in developing the income statement, which shows whether a company made money in the period being examined. (For the lowdown on income statements, see Chapter 19.) Credits and debits are pretty straightforward when it comes to the Sales account: Credits increase the account, and debits decrease it. The Sales account usually carries a credit balance, which is a good thing because it means the company had income.

What’s that, you say? The Sales account should carry a credit balance? That may sound strange, so let me explain the relationship between the Sales account and the balance sheet. The Sales account is one of the accounts that feed the bottom line of the income statement, which shows whether your business made a profit or suffered a loss. A profit means that you earned more through sales than you paid out in costs or expenses. Expense and cost accounts usually carry a debit balance.

The income statement’s bottom line figure shows whether the company made a profit. If Sales account credits exceed expense and cost account debits, the company made a profit. That profit would be in the form of a credit, which then gets added to the Equity account called Retained Earnings, which tracks how much of your company’s profits were reinvested into the company to grow the business. If the company lost money and the bottom line of the income statement showed that cost and expenses exceeded sales, the number would be a debit. That debit would be subtracted from the balance in Retained Earnings, to show the reduction to profits reinvested in the company.

Figure 4-12: Sales account in the General Ledger.

If your company earns a profit at the end of the accounting period, the Retained Earnings account increases thanks to a credit from the Sales account. If you lose money, your Retained Earnings account decreases.

After you post all the Ledger entries, you need to record details about where you posted the transactions on the journal pages. I show you how to do that in Chapter 5.

Adjusting for Ledger Errors

Your entries in the General Ledger aren’t cast in stone. If necessary, you can always change or correct an entry with what’s called an adjusting entry. Four of the most common reasons for General Ledger adjustments are

Depreciation: A business shows the aging of its assets through depreciation. Each year, a portion of the original cost of an asset is written off as an expense, and that change is noted as an adjusting entry. Determining how much should be written off is a complicated process that I explain in greater detail in Chapter 12.

Depreciation: A business shows the aging of its assets through depreciation. Each year, a portion of the original cost of an asset is written off as an expense, and that change is noted as an adjusting entry. Determining how much should be written off is a complicated process that I explain in greater detail in Chapter 12.

Prepaid expenses: Expenses that a company pays upfront, such as a year’s worth of insurance, are allocated by the month by using an adjusting entry. This type of adjusting entry is usually done as part of the closing process at the end of an accounting period. I show you how to develop entries related to prepaid expenses in Chapter 17.

Prepaid expenses: Expenses that a company pays upfront, such as a year’s worth of insurance, are allocated by the month by using an adjusting entry. This type of adjusting entry is usually done as part of the closing process at the end of an accounting period. I show you how to develop entries related to prepaid expenses in Chapter 17.

Adding an account: You can add accounts by way of adjusting entries at any time during the year. If you’re creating the new account to separately track transactions that once appeared in another account, you must move all transactions already in the books to the new account. You do this transfer with an adjusting entry to reflect the change.

Adding an account: You can add accounts by way of adjusting entries at any time during the year. If you’re creating the new account to separately track transactions that once appeared in another account, you must move all transactions already in the books to the new account. You do this transfer with an adjusting entry to reflect the change.

Deleting an account: You should only delete accounts at the end of an accounting period. I show you the type of entries you need to make in the General Ledger below.

Deleting an account: You should only delete accounts at the end of an accounting period. I show you the type of entries you need to make in the General Ledger below.

I talk more about adjusting entries and how you can use them in Chapter 17.

Practice: Posting to the General Ledger

Q. The entry developed for the General Ledger from the summary on Page 2 of the Purchases journal on May 31 was

|

Account |

Debit |

Credit |

|

Purchases |

$4,250 |

|

|

Accounts Payable |

$4,250 |

How do you record this entry into the General Ledger accounts of Purchases and Accounts Payable?

A. Review Figures 4-13 and 4-14 to see how to post these entries to General Ledger accounts.

Each account in the General Ledger has a separate page or pages. Entries are made from journals or directly to the General Ledger throughout the month. At the end of the month, the account balance is totaled. I talk more about how to close the books out at the end of the month or end of another accounting period, such as a quarter or year, in Chapter 22.

You can see that the date of the entry is placed in the first column. Next, you find a description indicating the source of the entry, followed by a reference number (which for a journal entry would be the page of the journal on which it’s found); then you post any debits to the debit column and any credits to the credit column.

Figure 4-13: Sample of a General Ledger page for the Purchases account.

Figure 4-14: Sample of a General Ledger page for the Accounts Payable account.

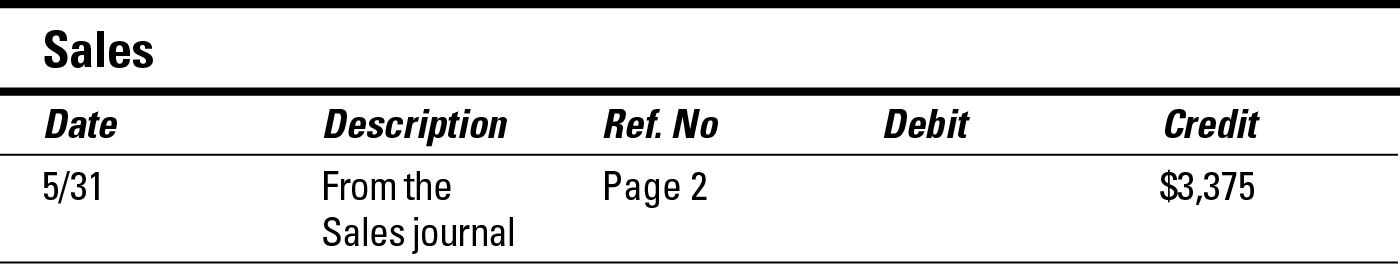

4. How do you post this journal entry, developed using the information on page 2 of the Sales journal on May 31, to the General Ledger?

|

Account |

Debit |

Credit |

|

Accounts Receivable |

$3,375 |

|

|

Sales |

$3,375 |

Solve It

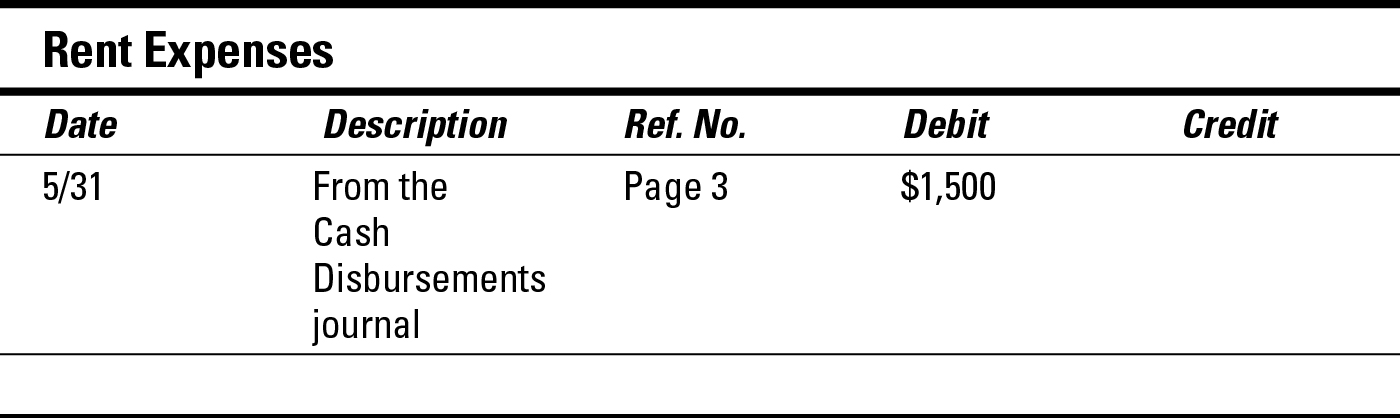

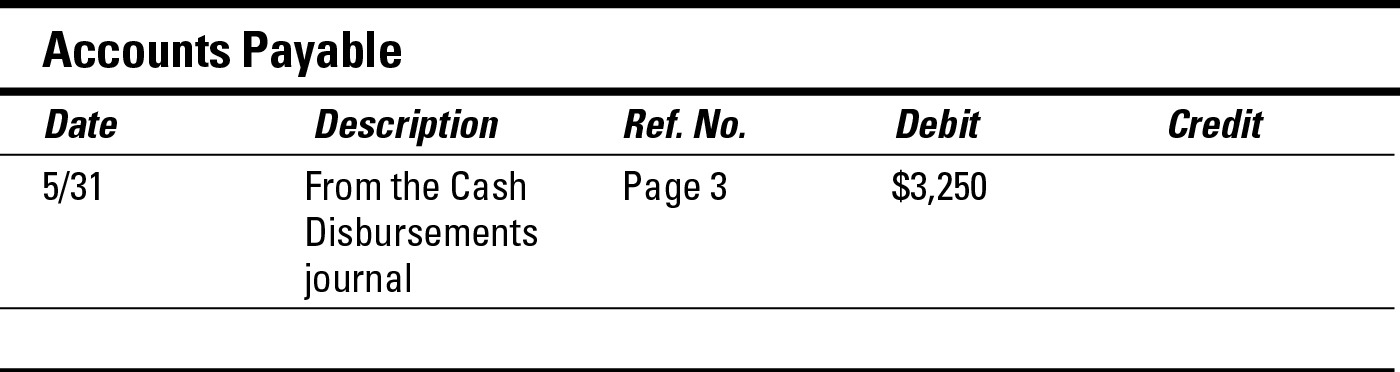

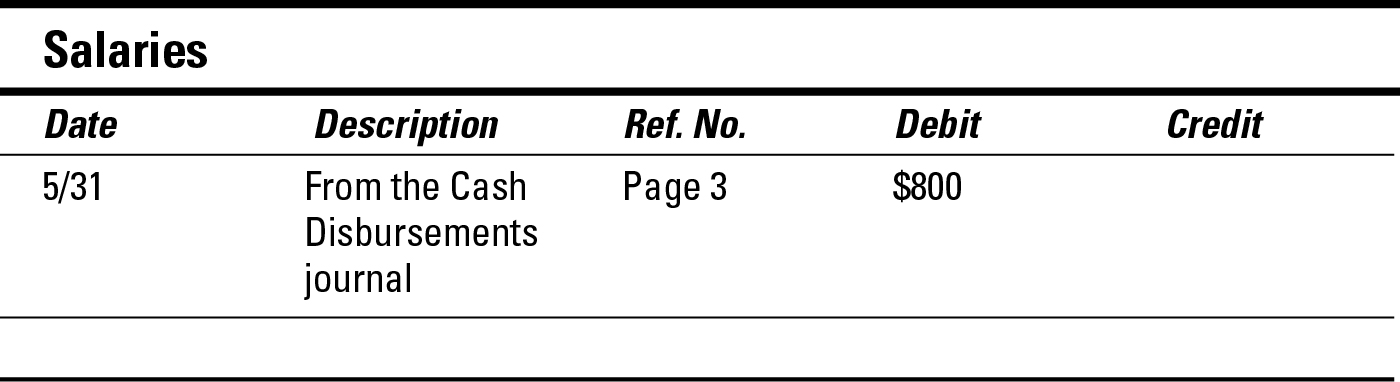

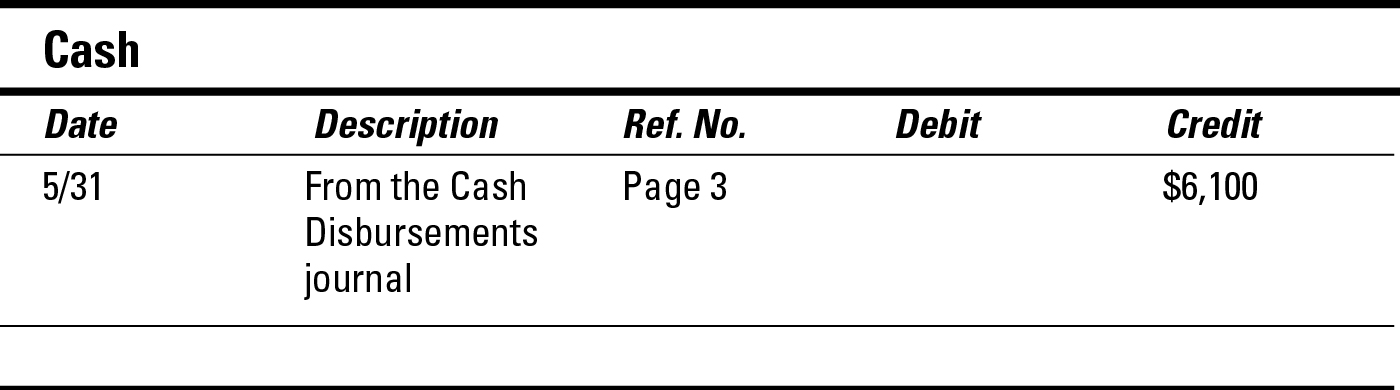

5. How do you post this journal entry, developed using the information on page 3 of the Cash Disbursements journal on May 31, to the General Ledger?

|

Account |

Debit |

Credit |

|

Rent |

$1,500 |

|

|

Accounts Payable |

$3,250 |

|

|

Credit Card Payable |

$550 |

|

|

Salaries |

$800 |

|

|

Cash |

$6,100 |

Solve It

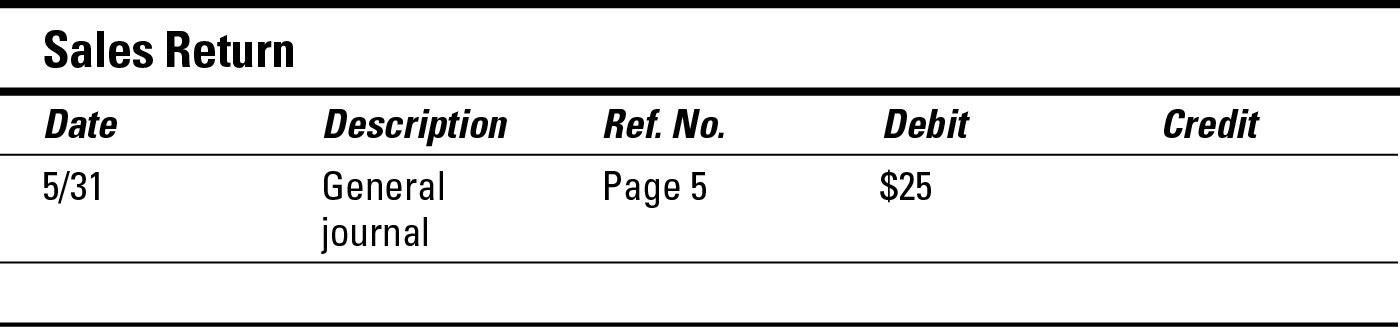

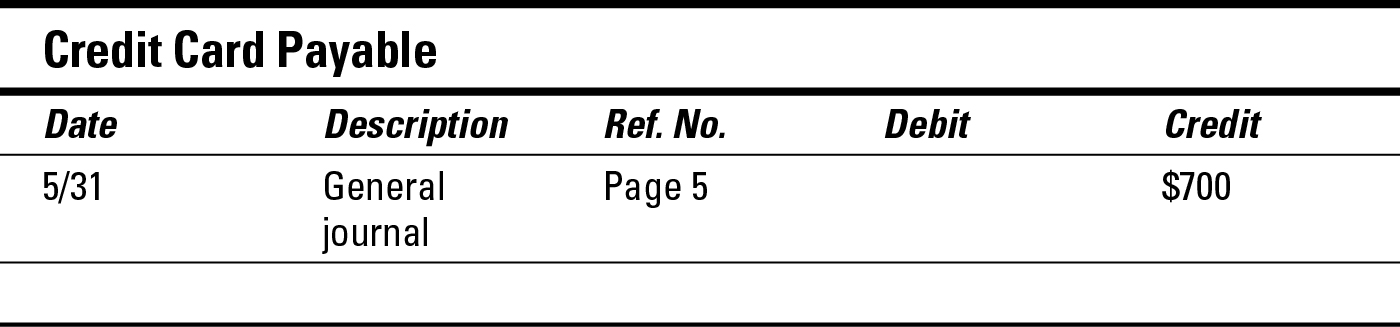

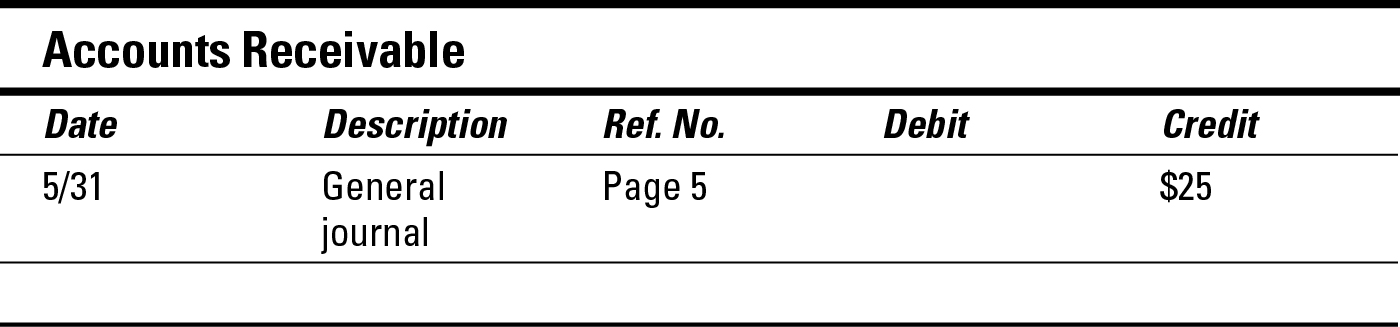

6. How do you post this journal entry, developed using the information on page 5 of the General journal on May 31, to the General Ledger?

|

Account |

Debit |

Credit |

|

Sales Return |

$25 |

|

|

Accounts Payable |

$550 |

|

|

Office Furniture |

$700 |

|

|

Purchases Return |

$550 |

|

|

Credit Card Payable |

$700 |

|

|

Accounts Receivable |

$25 |

Solve It

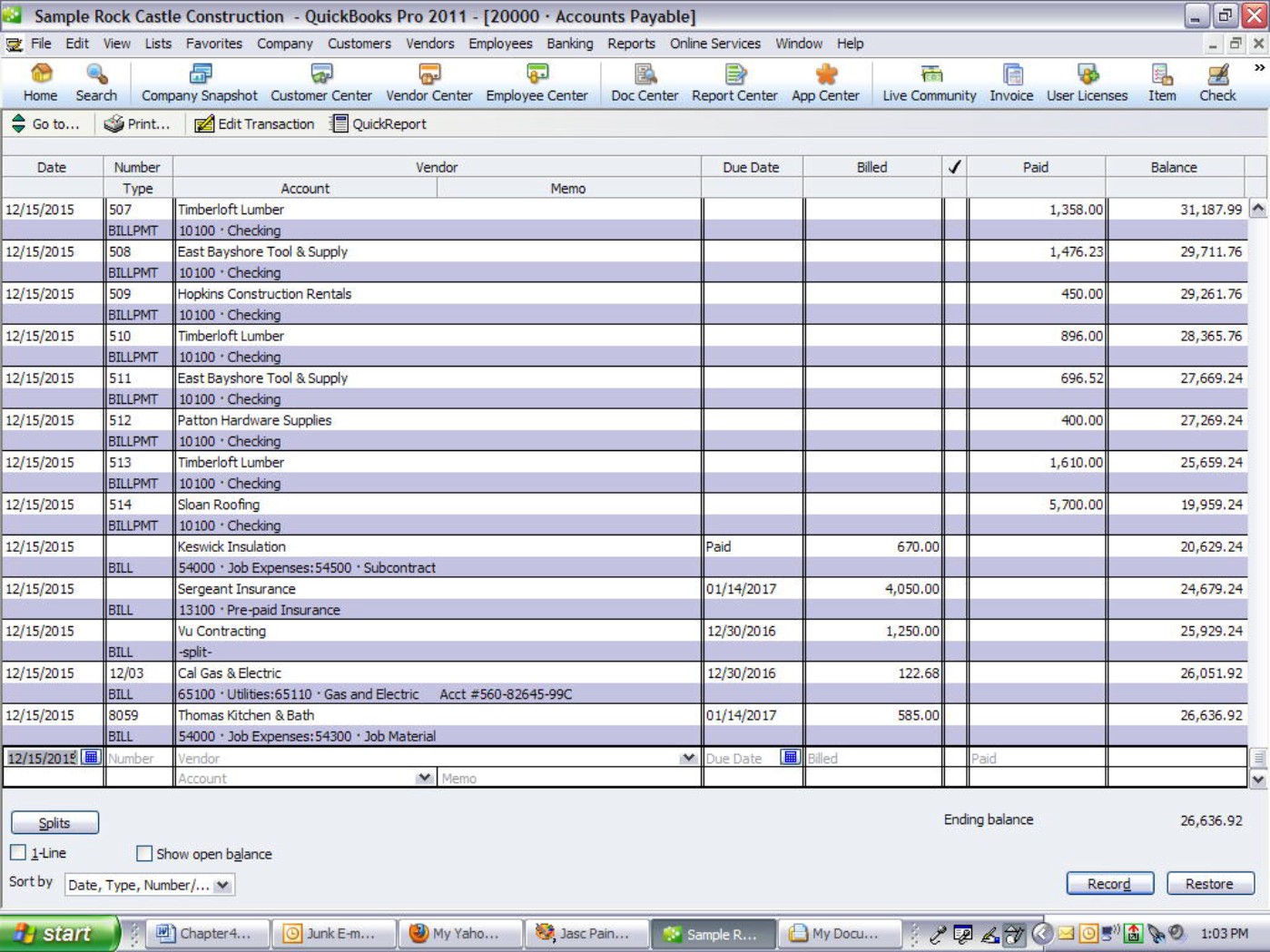

Using Computerized Transactions to Post and Adjust in the General Ledger

If you use a computerized accounting system to keep your books, your accounting software actually posts to the General Ledger behind the scenes. You can view your transactions right on the screen. I show you how using two simple steps in QuickBooks without ever having to make a General Ledger entry. Note: Other computerized accounting programs allow you to view transactions right on the screen, too. I’m using QuickBooks for examples throughout the book, because it’s the most popular of the computerized accounting systems.

Here’s how it works:

1. Click on the Chart of Accounts (see Figure 4-15).

2. Click on the account for which you want more detail.

In Figure 4-16, I look into Accounts Payable and see the transactions for December that were entered when the bills were paid.

Figure 4-15: A Chart of Accounts as it appears in QuickBooks.

Image Credit: Intuit

Figure 4-16: Peek inside the Accounts Payable account in QuickBooks.

Image Credit: Intuit

If you need to make an adjustment to a payment that appears in your computerized system, highlight the transaction, click on Edit Transaction in the line below the account name, and make the necessary changes.

Answers to Problems on Ledgers

The following are the answers to the practice problems presented throughout this chapter.

1. Here’s the General Ledger entry:

|

Account |

Debit |

Credit |

|

Accounts Receivable |

$3,375 |

|

|

Sales |

$3,375 |

2. Here’s the General Ledger entry:

|

Account |

Debit |

Credit |

|

Rent |

$1,500 |

|

|

Accounts Payable |

$3,250 |

|

|

Credit Card Payable |

$550 |

|

|

Salaries |

$800 |

|

|

Cash |

$6,100 |

Note that in this case, the accounts that were posted to a specific company aren’t listed individually. A Purchase Return is a product that you intended to sell but returned to a vendor. Therefore, you reduce the amount you owe that vendor by debiting Accounts Payable, which would reduce the amount due in Accounts Payable. When a customer returns a product to you, you must reduce the amount the customer owes. You not only reduce the amount in that customer’s account but also credit Accounts Receivable, where you track payments due from customers.

3. Here’s the General Ledger entry:

|

Account |

Debit |

Credit |

|

Sales Return |

$25 |

|

|

Accounts Payable |

$550 |

|

|

Office Furniture |

$700 |

|

|

Purchase Return |

$550 |

|

|

Credit Card Payable |

$700 |

|

|

Accounts Receivable |

$25 |

4. Here’s how you post the information to the Accounts Receivable and Sales accounts of the General Ledger:

5. Here’s how you post the information from the Cash Disbursements journal:

6. Here’s how you post the information from the General journal:

Note that the Debits and Credits are in balance — $2,900 each. Remember, all entries to the General Ledger must be balanced entries. That’s the cardinal rule of double-entry bookkeeping. For more detail about double-entry bookkeeping, read Chapter 2.

Note that the Debits and Credits are in balance — $2,900 each. Remember, all entries to the General Ledger must be balanced entries. That’s the cardinal rule of double-entry bookkeeping. For more detail about double-entry bookkeeping, read Chapter 2. As you navigate the General Ledger created by your computerized book-keeping system, you can see how easily someone can make changes that alter your financial transactions and possibly cause serious harm to your business. For example, someone may reduce or alter your bills to customers or change the amount due to a vendor. Be sure that you can trust whoever has access to your computerized system and that you’ve set up secure password access. Also, establish a series of checks and balances for managing your business’s cash and accounts. Chapter 7 covers safety and security measures in greater detail.

As you navigate the General Ledger created by your computerized book-keeping system, you can see how easily someone can make changes that alter your financial transactions and possibly cause serious harm to your business. For example, someone may reduce or alter your bills to customers or change the amount due to a vendor. Be sure that you can trust whoever has access to your computerized system and that you’ve set up secure password access. Also, establish a series of checks and balances for managing your business’s cash and accounts. Chapter 7 covers safety and security measures in greater detail.