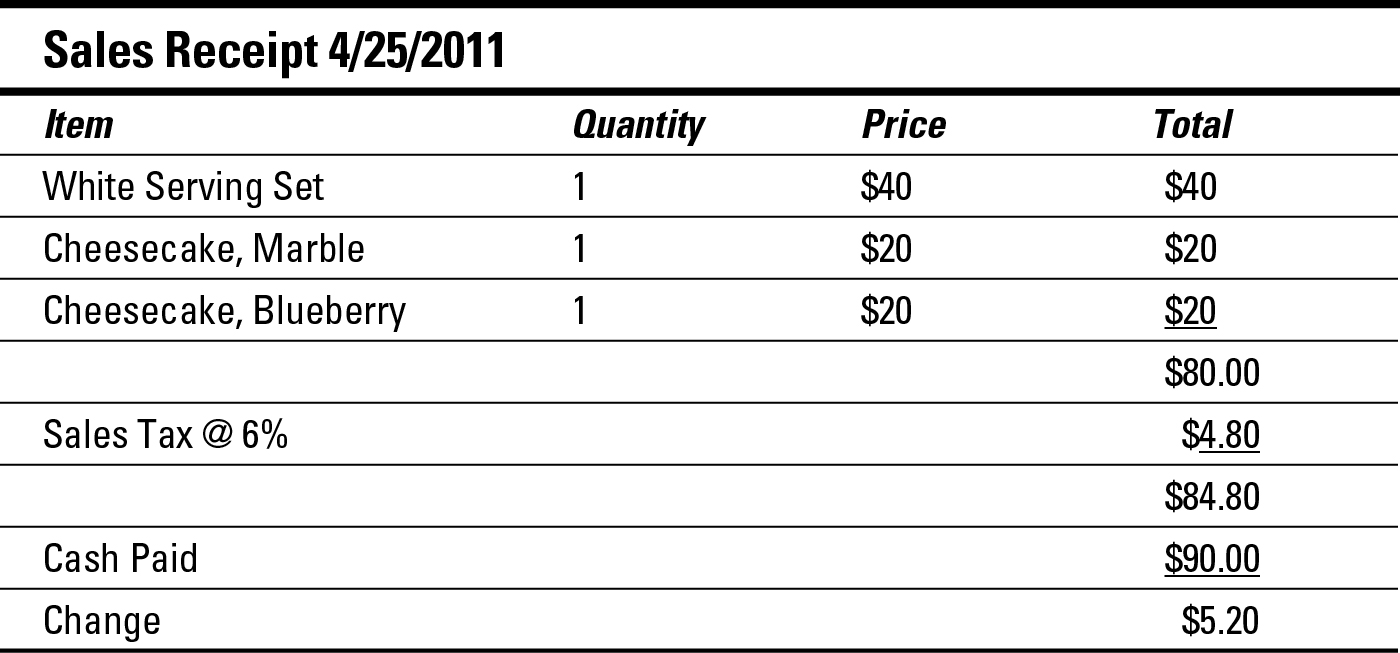

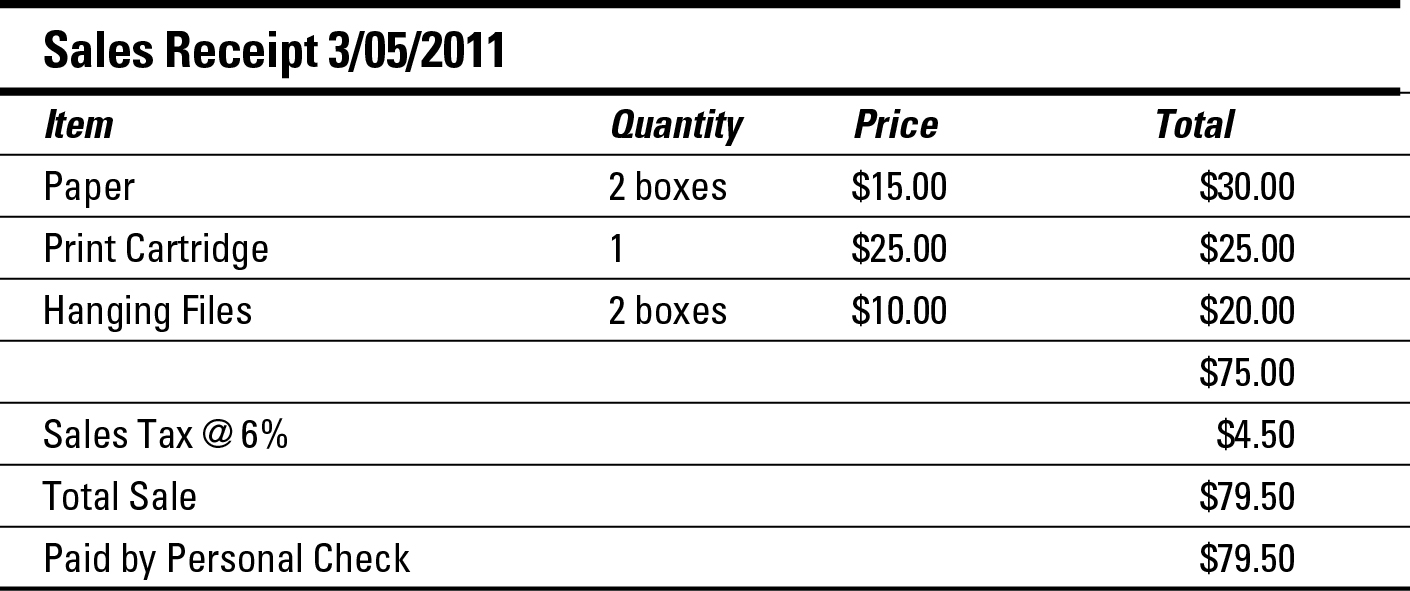

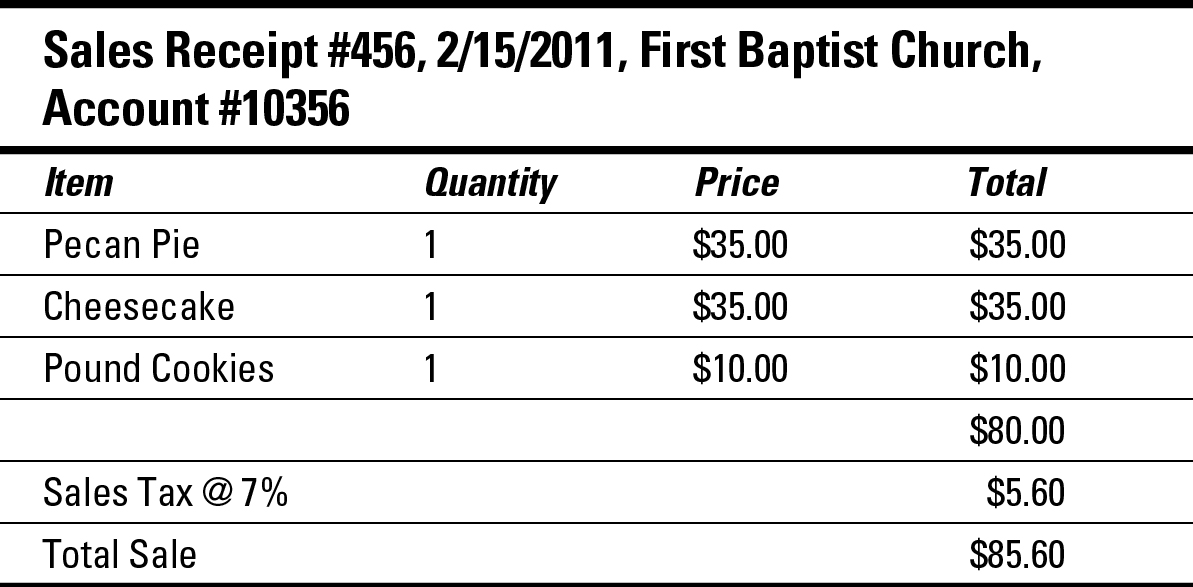

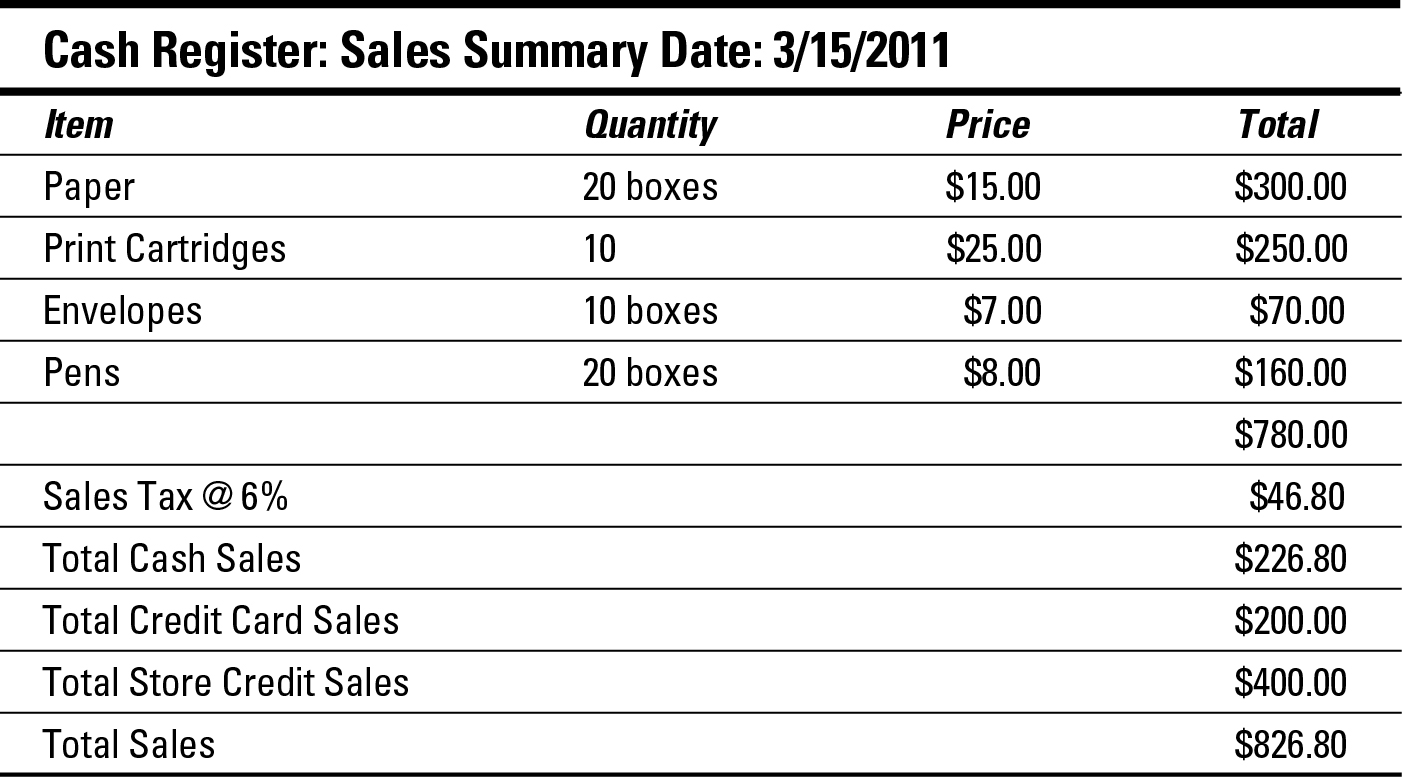

Figure 9-1: Example of a sales receipt in QuickBooks.

Chapter 9

Counting Your Sales

In This Chapter

Taking in cash

Taking in cash

Discovering the ins and outs of store credit

Discovering the ins and outs of store credit

Managing discounts for best results

Managing discounts for best results

Staying on top of returns and allowances

Staying on top of returns and allowances

Monitoring payments due and dealing with bad debt

Monitoring payments due and dealing with bad debt

Every business loves to take in money, and that means you, the bookkeeper, have a lot to do to make sure sales are properly tracked and recorded in the books. In addition to recording the sales themselves, you must track customer accounts, discounts offered to customers, and customer returns and allowances.

If the company sells products on store credit, you have to carefully monitor customer accounts in Accounts Receivable, including monitoring whether customers pay on time and alerting the sales team if customers are behind on their bills and future purchases on credit need to be denied. Some customers never pay, and in that case, you must adjust the books to reflect nonpayment as a bad debt.

This chapter reviews the basic responsibilities that fall to a business’s bookkeeping and accounting staff for tracking sales, making adjustments to those sales, monitoring customer accounts, and notifying management of slow-paying customers.

Collecting on Cash Sales

Most businesses collect some form of cash as payment for the goods or services they sell. Cash receipts include more than just bills and coins; checks and credit cards also are considered cash sales for the purpose of bookkeeping. In fact, with electronic transaction processing (that’s when a customer’s credit card is swiped through a machine), a deposit is usually made to the business’s checking account the same day (sometimes within just seconds of the transaction, depending on the type of system the business sets up with the bank).

Discovering the value of sales receipts

Modern businesses generate sales slips in one of three ways: by the cash register, by the credit card machine, or by hand (written out by the salesperson). Whichever of these three methods you choose to handle your sales transactions, the sales receipt serves two purposes:

Gives the customer proof that the item was purchased on a particular day at a particular price in your store in case he needs to exchange or return the merchandise.

Gives the customer proof that the item was purchased on a particular day at a particular price in your store in case he needs to exchange or return the merchandise.

Gives the store a receipt that can be used at a later time to enter the transaction into the company’s books. At the end of the day, the receipts also are used to prove out (show that they have the right amount of cash in the register based on the sales transactions during the day) the cash register and ensure that the cashier has taken in the right amount of cash based on the sales made. (In Chapter 7, I talk more about how cash receipts can be used as an internal control tool to manage your cash.)

Gives the store a receipt that can be used at a later time to enter the transaction into the company’s books. At the end of the day, the receipts also are used to prove out (show that they have the right amount of cash in the register based on the sales transactions during the day) the cash register and ensure that the cashier has taken in the right amount of cash based on the sales made. (In Chapter 7, I talk more about how cash receipts can be used as an internal control tool to manage your cash.)

I’m sure you’re familiar with cash receipts, but just to show you how much useable information can be generated for the bookkeeper on a sales receipt, here’s a sample receipt from a sale at a bakery:

You’ve probably never thought about how much bookkeeping information is included on a sales receipt, but receipts contain a wealth of information that’s collected for your company’s accounting system. A look at a receipt tells you the amount of cash collected, the type of products sold, the quantity of products sold, and how much sales tax was collected.

Unless your company uses some type of computerized system at the point of sale (which is usually the cash register) that’s integrated into the company’s accounting system, sales information is collected throughout the day by the cash register and printed out in a summary form at the end of the day. At that point, you enter the details of the sales day in the books.

If you don’t use your computerized system to monitor inventory, you use the data collected by the cash register to simply enter into the books the cash received, total sales, and sales tax collected. Although in actuality, you’d have many more sales and much higher numbers at the end of the day, here’s what an entry in the Cash Receipts journal would look like for the receipt:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Cash in Checking |

$84.80 |

|

|

Sales |

$80.00 |

|

|

Sales Tax Collected |

$4.80 |

|

|

Cash receipts for 4/25/2011 |

||

In this example entry, Cash in Checking is an asset account shown on the balance sheet (see Chapter 18 for more about balance sheets), and its value increases with the debit. The Sales account is a revenue account on the income statement (see Chapter 19 for more about income statements), and its balance increases with a credit, showing additional revenue. (I talk more about debits and credits in Chapter 2.) The Sales Tax Collected account is a Liability account that appears on the balance sheet, and its balance increases with this transaction.

Recording cash transactions in the books

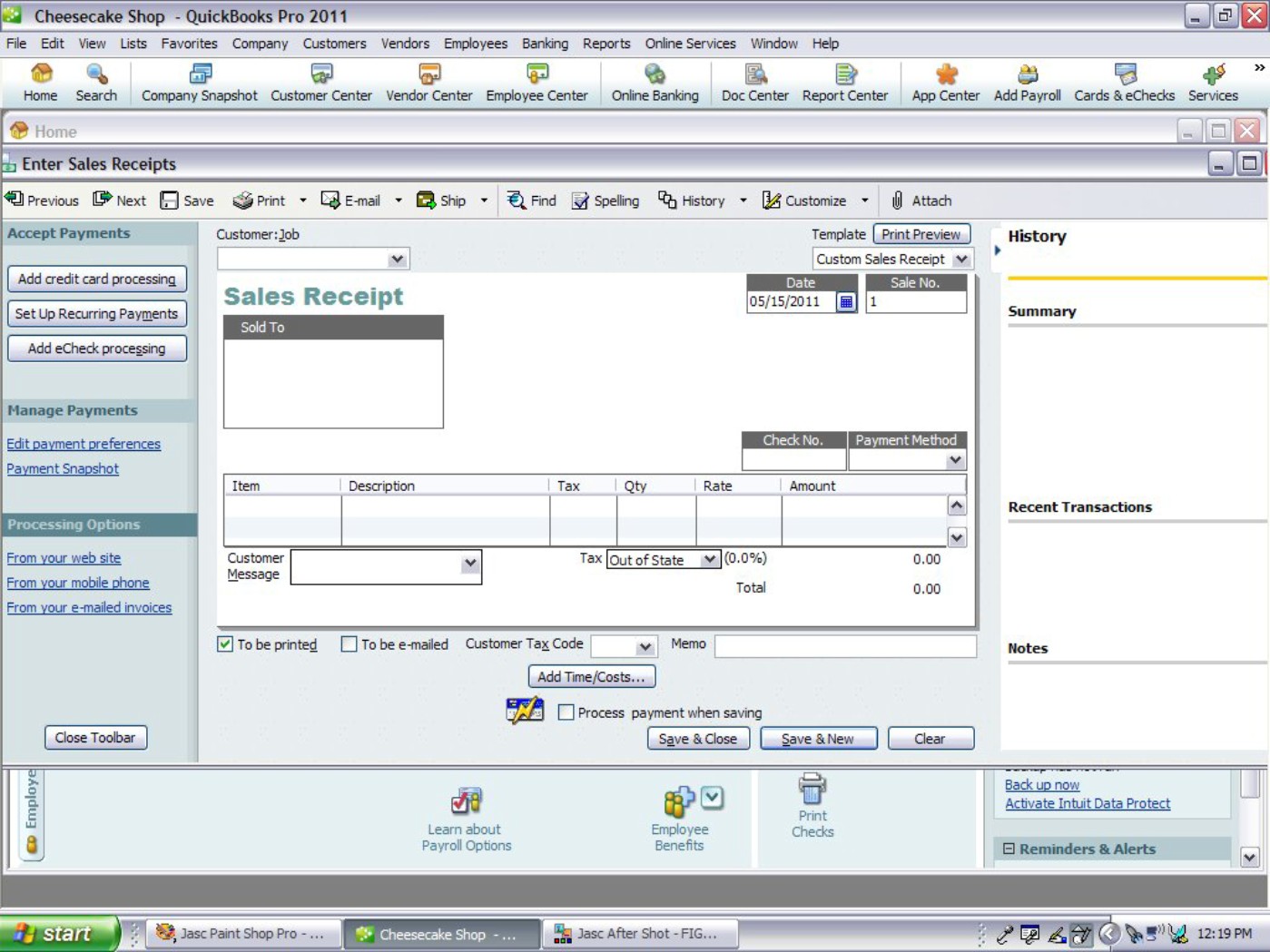

Image Credit: Intuit

In addition to the information included in the Cash Receipts journal, note that QuickBooks also collects information about the items sold in each transaction. QuickBooks then automatically updates inventory information, reducing the amount of inventory on hand when necessary. When the inventory number falls below the reorder number you set (see Chapter 8), QuickBooks alerts you to pass the word on to whoever is responsible for ordering to order more inventory.

If the sales receipt in Figure 9-1 were for an individual customer, you’d enter his or her name and address in the “Sold To” field. At the bottom of the receipt, you can see a section asking whether you want to print or e-mail the receipt; you can print the receipt and give it to the customer or e-mail it to the customer if the order was made by phone or Internet. The bottom of the receipt also has a place to mark whether the item should be charged to a credit card. (For an additional fee, QuickBooks allows you to process credit card receipts when saving an individual cash receipt.)

Practice: Recording Sales in the Books

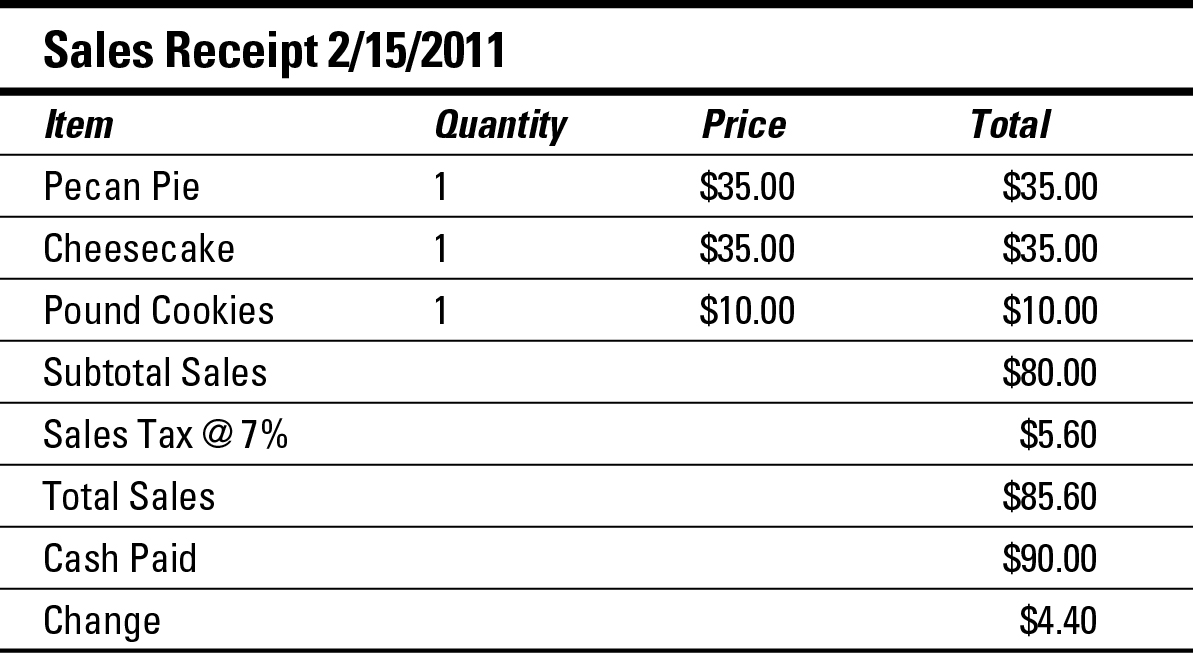

Q. How do you record the following transaction in your books?

A. The key numbers you need to use are Total Sales, Subtotal Sales, and Sales Tax. Here’s what the bookkeeping entry looks like:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Cash in Checking |

$85.60 |

|

|

Sales |

$80.00 |

|

|

Sales Tax Collected |

$5.60 |

|

|

Cash receipts for 2/25/2011 |

||

You record the information from this entry in your Sales journal (see Chapter 5). Note that you enter a debit to the Cash in Checking account and a credit to the Sales and Sales Tax Collected accounts. Equal amounts are posted to both the debits and the Credits. That should always be true; your bookkeeping entries should always be in balance. These entries would increase the amount in all three accounts. To understand more about how debits and credits work, read Chapter 2.

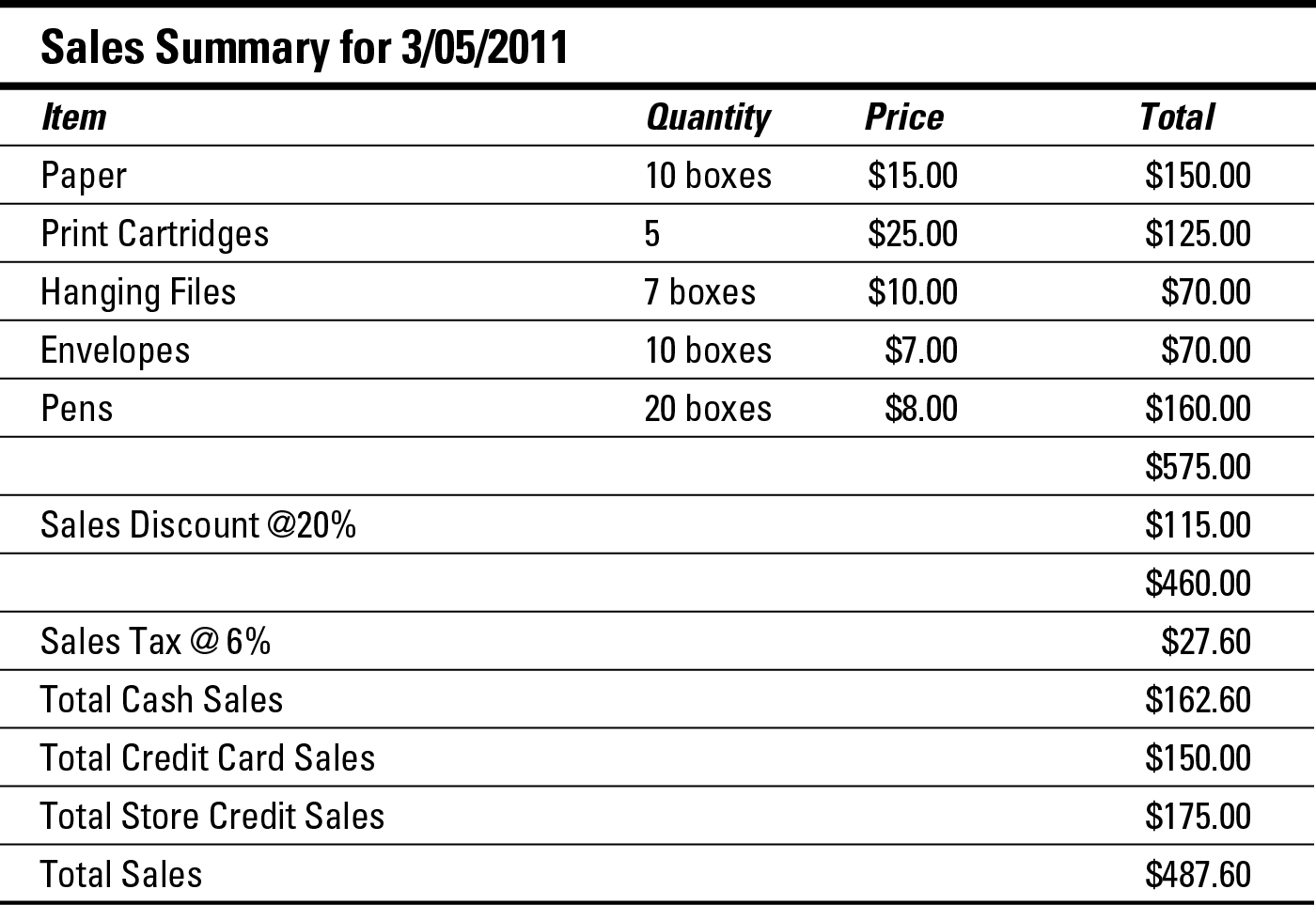

When you work for a company, you typically get a summary of total sales for the day and may not necessarily need to add up each receipt, depending on the types of cash registers used in your store. The entry into your books in that case would most likely be a total of cash sales on a daily basis.

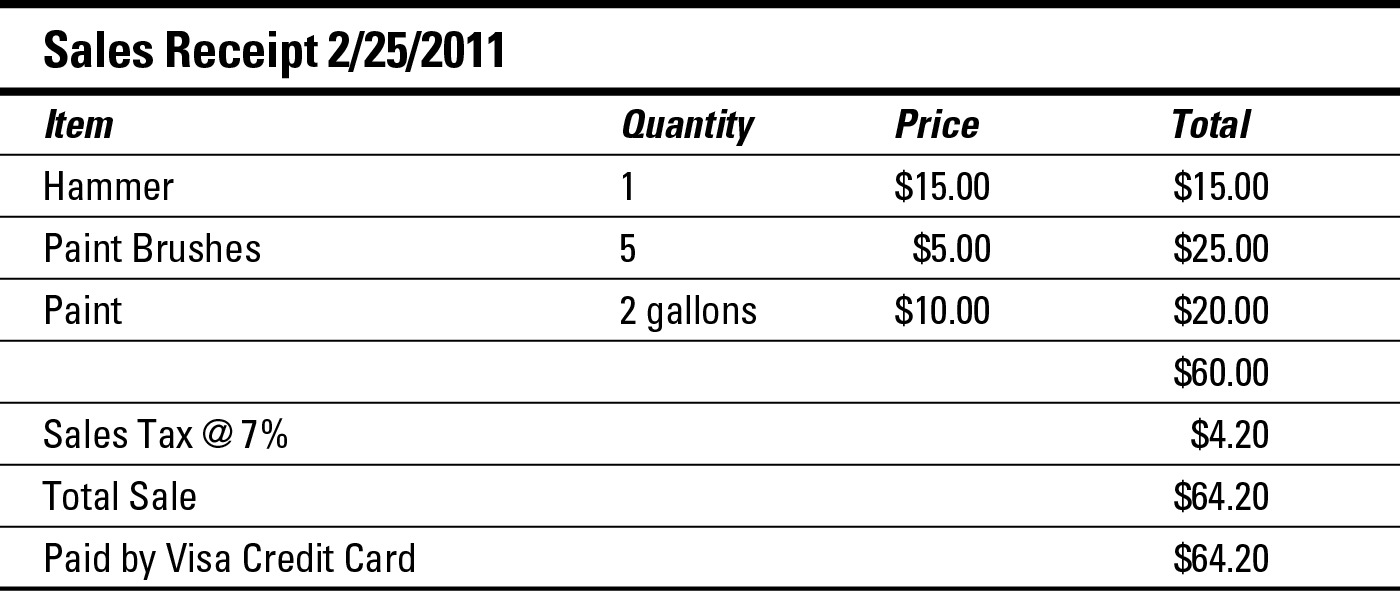

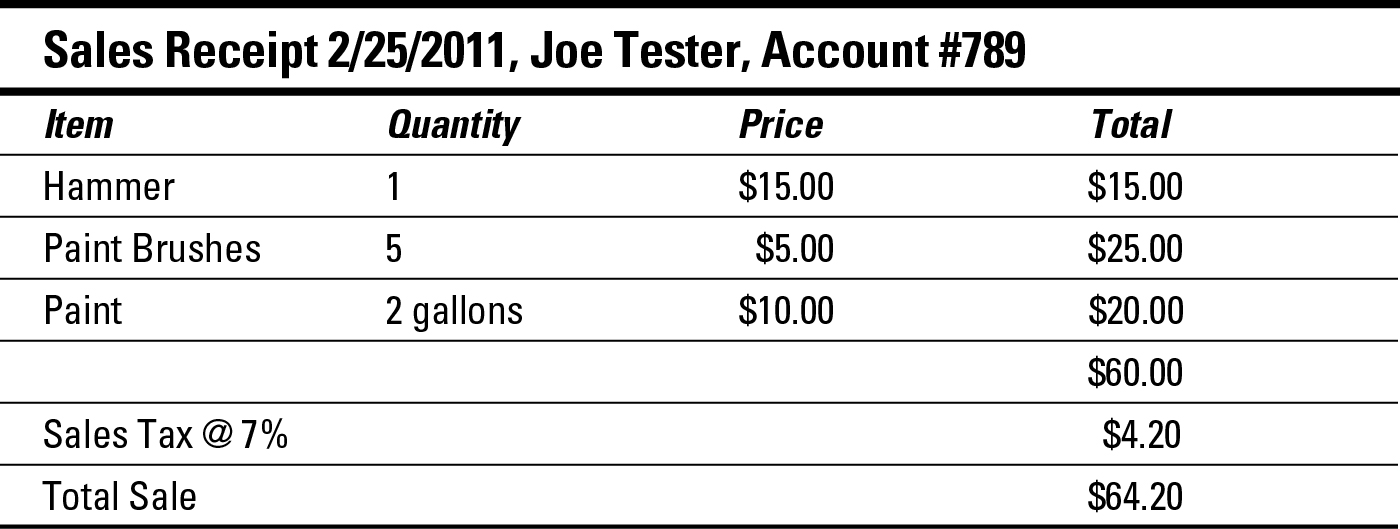

1. How do you record the following transaction in your books if you’re the bookkeeper for a hardware store?

Solve It

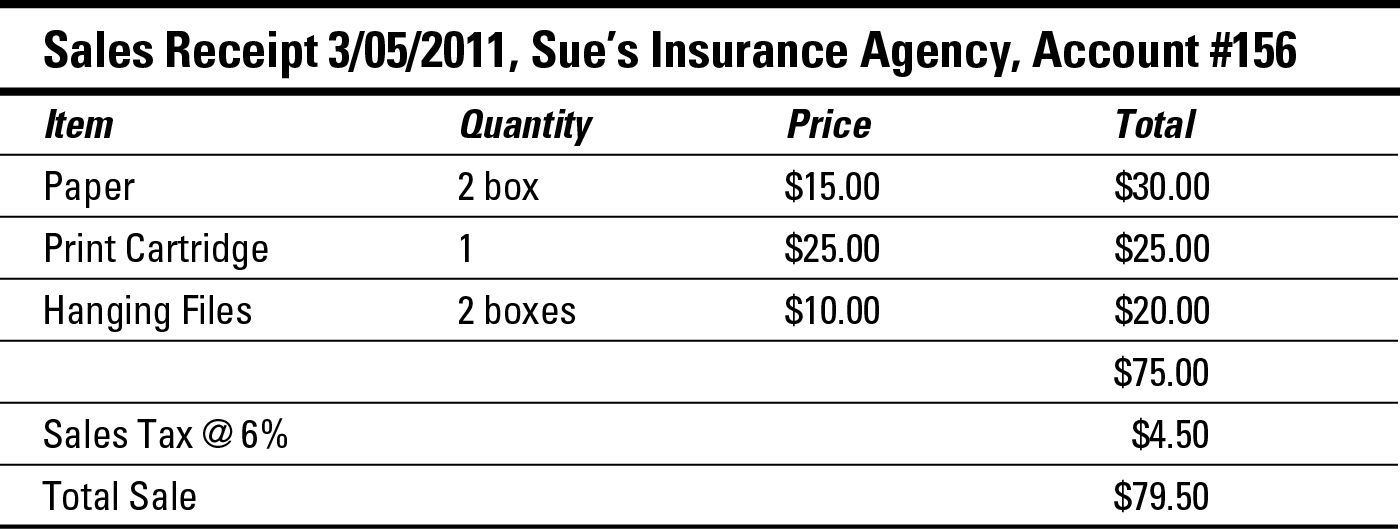

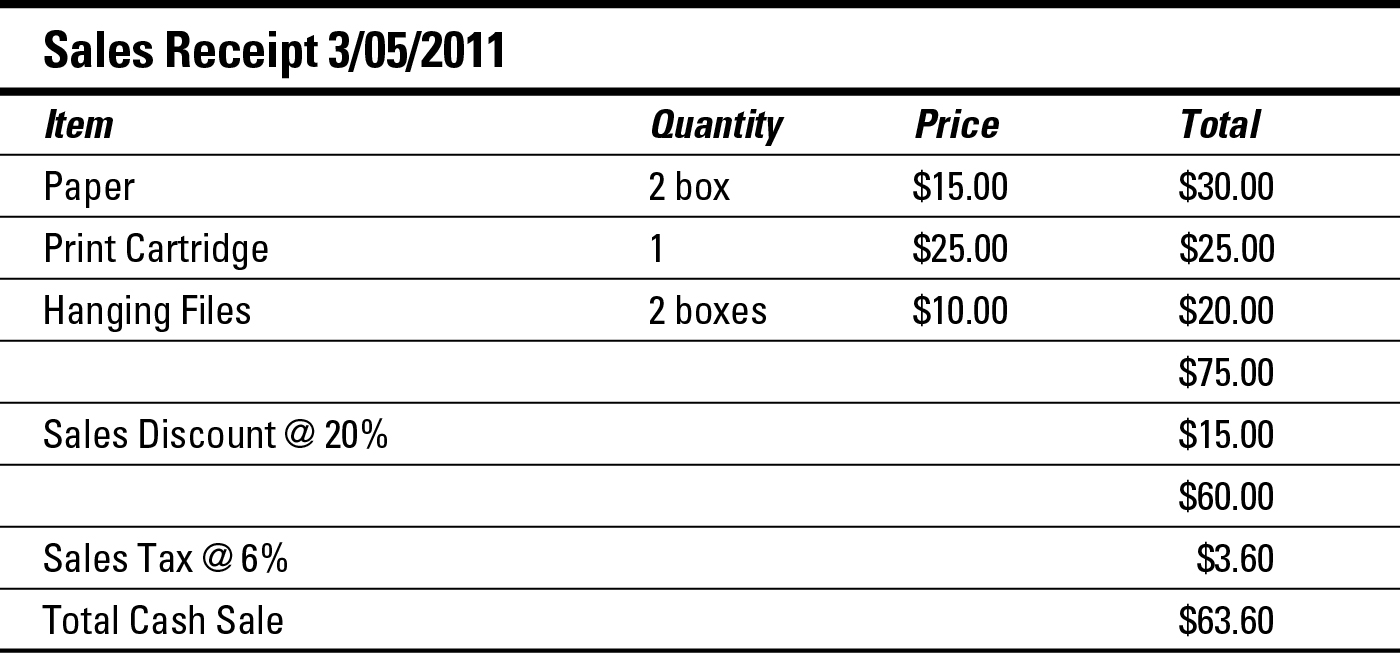

2. How do you record the following transaction in your books if you’re a bookkeeper for an office supply store?

Solve It

Selling on Credit

Many businesses decide to sell to customers on direct credit, meaning credit offered by the business and not through a bank or credit card provider. This approach offers more flexibility in the type of terms you can offer your customers, and you don’t have to pay bank fees. However, it involves more work for you, the bookkeeper, and more risk if a customer doesn’t pay what he or she owes.

Deciding whether to offer store credit

The decision to set up your own store credit system depends on what your competition is doing. For example, if you run an office supply store and all other office supply stores allow store credit to make it easier for their customers to get supplies, you probably need to offer store credit to stay competitive.

How you plan to check a customer’s credit history

How you plan to check a customer’s credit history

What the customer’s income level needs to be to be approved for credit

What the customer’s income level needs to be to be approved for credit

How long you give the customer to pay the bill before charging interest or late fees

How long you give the customer to pay the bill before charging interest or late fees

The harder you make it to get store credit and the stricter you make the bill-paying rules, the less chance you have of a taking a loss. However, you may lose customers to a competitor with lighter credit rules. For example, you may require a minimum income level of $50,000 and make customers pay in 30 days if they want to avoid late fees or interest charges. Your sales staff reports that these rules are too rigid because your direct competitor down the street allows credit on a minimum income level of $30,000 and gives customers 60 days to pay before late fees and interest charges.

Now you have to decide whether you want to change your credit rules to match the competition’s. But, if you do lower your credit standards to match your competitor, you may end up with more customers who can’t pay on time or at all because you’ve qualified customers for credit at lower income levels and given them more time to pay. If you loosen your qualification criteria and bill-paying requirements, you have to carefully monitor your customer accounts to be sure they’re not falling behind.

The key risk you face is selling product for which you’re never paid. For example, if you allow customers 30 days to pay and cut them off from buying goods if their accounts fall more than 30 days behind, the most you can lose is the amount purchased over a two-month period (60 days). But if you give customers more leniency, allowing them 60 days to pay and cutting them off after payment’s 30 days late, you’re faced with three months (90 days) of purchases for which you may never be paid.

Recording store credit transactions in the books

When sales are made on store credit, you have to enter specific information into the accounting system. In addition to inputting information regarding cash receipts (see “Collecting on Cash Sales” earlier in this chapter), you update the customer accounts to be sure each customer is billed and the money is collected. You debit the Accounts Receivable account, an asset account shown on the Balance Sheet (see Chapter 18), which shows money due from customers.

Here’s how a journal entry of a sale made on store credit looks:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Accounts Receivable |

$84.80 |

|

|

Sales |

$80.00 |

|

|

Sales Tax Collected |

$4.80 |

|

|

Cash receipts for 4/25/2011 |

||

In addition to making this journal entry, you enter the information into the customer’s account so that accurate bills can be sent out at the end of the month. When the customer pays the bill, you update the individual customer’s record to show that payment has been received and enter the following into the bookkeeping records:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Cash |

$84.80 |

|

|

Accounts Receivable |

$84.80 |

|

|

Payment from S. Smith on invoice 123. |

||

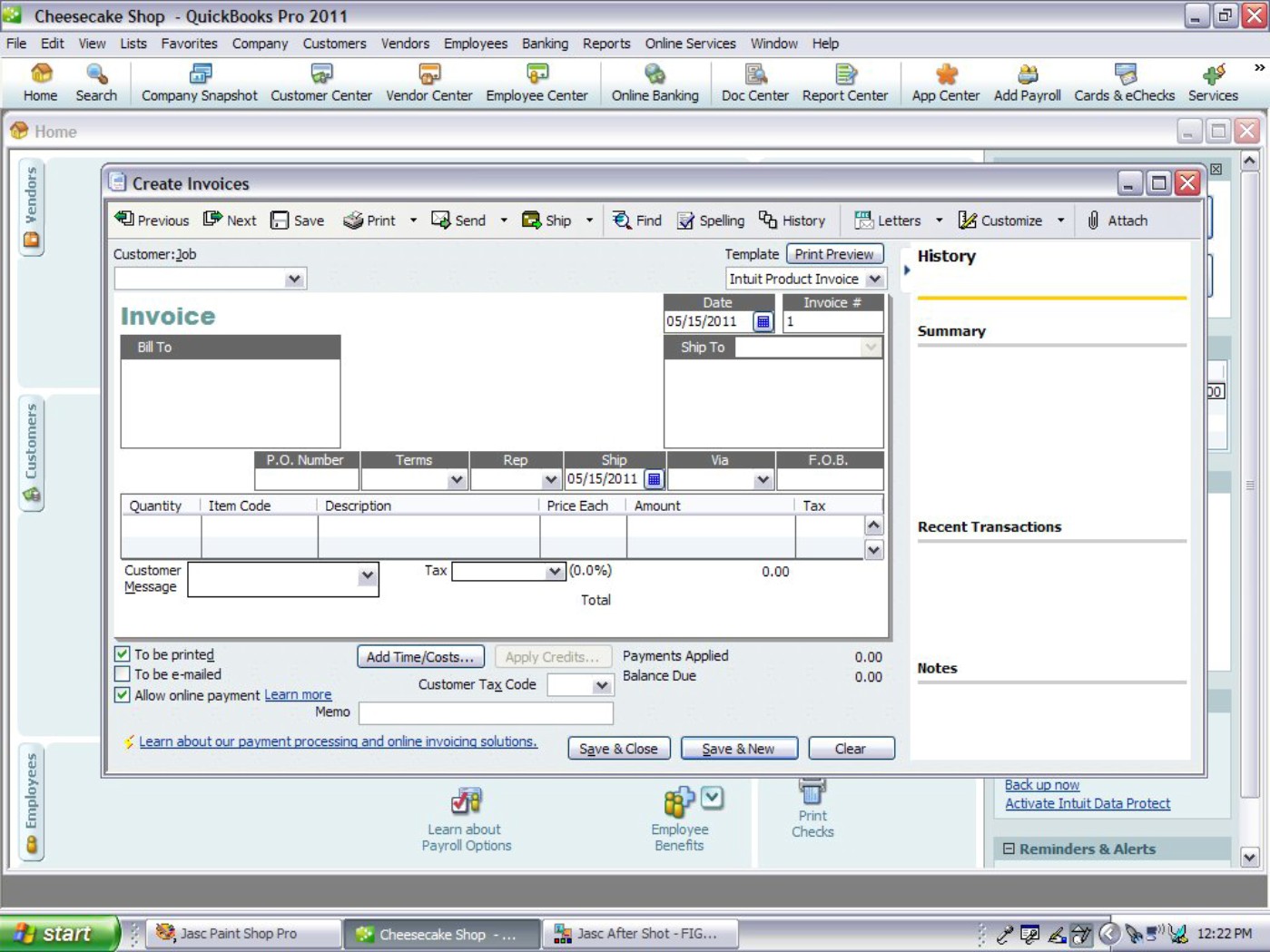

If you’re using QuickBooks, you enter purchases on store credit by using an invoice form like the one in Figure 9-2. Most of the information on the invoice form is similar to the sales receipt form (see “Collecting on Cash Sales”), but the invoice form also has space to enter a different address for shipping (the “Ship To” field) and includes payment terms (the “Terms” field). For the sample invoice form shown in Figure 9-2, you can see that payment is due in 30 days.

QuickBooks uses the information on the invoice form to update the following accounts:

Accounts Receivable

Accounts Receivable

Inventory

Inventory

The customer’s account

The customer’s account

Sales Tax Collected

Sales Tax Collected

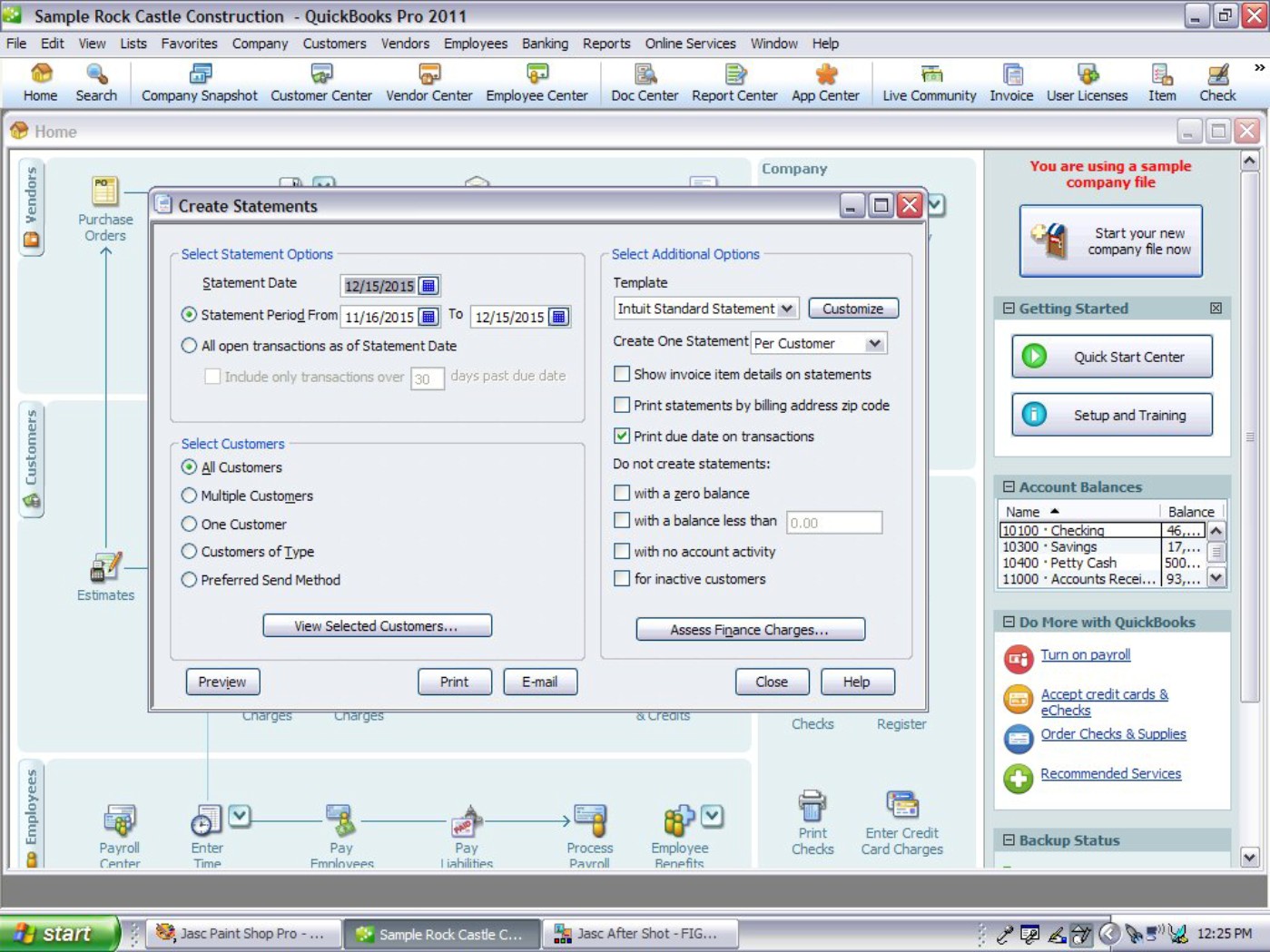

Based on this data, when it comes time to bill the customer at the end of the month, QuickBooks generates statements for all customers with outstanding invoices with a little prompting from you (see Figure 9-3). You can easily generate statements for specific customers or all customers on the books.

Figure 9-2: QuickBooks sales invoice for purchases made on store credit.

Image Credit: Intuit

Figure 9-3: Generating statements for customers with QuickBooks.

Image Credit: Intuit

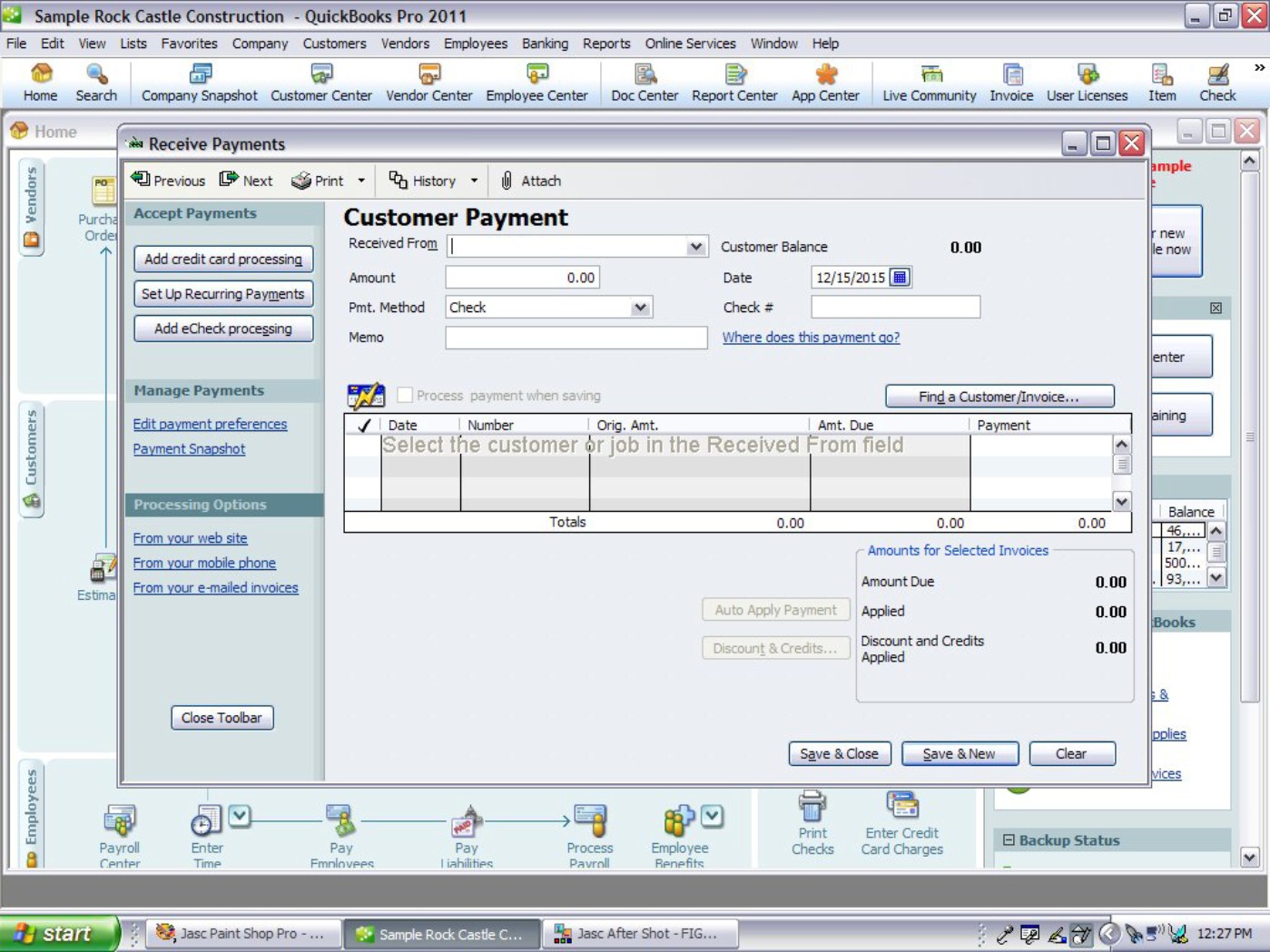

When you receive payment from a customer, here’s what happens:

1. You enter the customer’s name on the customer payment form (shown in Figure 9-4).

2. QuickBooks automatically lists all outstanding invoices.

3. You select the invoice or invoices paid.

4. QuickBooks updates the Accounts Receivable account, the Cash account, and the customer’s individual account to show that payment has been received.

If your company uses a point of sale program that’s integrated into the computerized accounting system, recording store credit transactions is even easier for you. Sales details feed into the system as each sale is made, so you don’t have to enter the detail at the end of day. These point of sale programs save a lot of time, but they can get very expensive — usually at least $500 for just one cash register.

Even if customers don’t buy on store credit, point of sale programs provide businesses with an incredible amount of information about their customers and what they like to buy. This data can be used in the future for direct marketing and special sales to increase the likelihood of return business.

Figure 9-4: In Quick-Books, recording payments from customers who bought on store credit starts with the Customer Payment form.

Image Credit: Intuit

Practice: Sales on Store (Direct) Credit

Q. Suppose you’re the bookkeeper for a bakery that allows customers to buy on store credit. How do you record the following sales transaction in your books?

A. The key numbers you need to use are Total Sales, Subtotal Sales, and Sales Tax. You also need the customer name and account number. Here’s what the bookkeeping entry looks like:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Accounts Receivable |

$85.60 |

|

|

Sales |

$80.00 |

|

|

Sales Tax Collected |

$5.60 |

|

|

Credit receipts for 2/25/2011 |

||

In addition to recording the sales transaction in your Sales Journal, you also need to record the transaction in the customer’s account, whether that’s on a computer worksheet, in a paper journal, or on cards for each customer. Whichever way your company tracks individual customer accounts, here’s the entry that you need to make to the account of the First Baptist Church:

2/15/2011 Baked Goods — Sales Receipt #456 $85.60

When you record a transaction in a customer’s account, you want to be sure you have enough identifying information to be able to find the original sales transaction in case the customer questions the charge when you send the bill at the end of the month.

In the later section “Monitoring Accounts Receivable,” I show you how to use this information to bill and collect from your customers.

3. Suppose you’re the bookkeeper for a hardware store that allows customers to buy on store credit. How do you record the following sales transaction in your books?

Solve It

4. Suppose you’re the bookkeeper for an office supply store that allows customers to buy on store credit. How do you record the following sales transaction in your books?

Solve It

Proving Out the Cash Register

To ensure that cashiers don’t pocket a business’s cash, at the end of each day, cashiers must prove out the amount in cash, checks, and charges they took in during the day.

This process of proving out a cash register actually starts at the end of the previous day, when a cashier and his manager agree to the amount of cash left in the cash register drawer. Cash sitting in cash registers or cash drawers is recorded as part of the Cash on Hand account.

You monitor cash by knowing exactly how much cash was in the register at the beginning of the day and then checking how much cash is left at the end of the day. You should count the cash at the end of the day as soon as all sales transactions have been completed and print out a summary of all transactions. In many companies, the sales manager actually cashes out the register at night with the cashiers and gives you the copy of the completed cash-out form. Here’s one example of a cash-out form:

Cash Register: _____ Date: _____

|

Receipts |

Sales |

Cash in Register |

|

Beginning Cash |

_____ |

_____ |

|

Cash Sales |

_____ |

_____ |

|

Credit Card Sales |

_____ |

_____ |

|

Store Credit Sales |

_____ |

_____ |

|

Total Sales |

_____ |

_____ |

|

Minus Sales on Credit |

_____ |

_____ |

|

Total Cash Received |

_____ |

_____ |

|

Total Cash that Should Be in Register |

_____ |

|

|

Actual Cash in Register |

_____ |

|

|

Difference |

_____ |

A store manager reviews the cashier’s cash register summary (produced by the actual register) and compares it to the cash-out form. If the ending cash (the amount of cash remaining in the register) doesn’t match the cash-out form, the cashier and the manager try to pinpoint the mistake. If they can’t find a mistake, they fill out a cash-overage or cash-shortage form. Some businesses charge the cashier directly for any shortages, while others take the position that the cashier will be fired after a certain number of shortages of a certain dollar amount (say, three shortages of more than $10).

The store manager decides how much cash to leave in the cash drawer or register for the next day and deposits the remainder. He does this task for each of his cashiers and then deposits all the cash and checks from the day in a night deposit box at the bank. He sends a report with details of the deposit to the bookkeeper so that the data makes it into the accounting system. The bookkeeper enters the data on the Cash Receipts form (see Figure 9-1 earlier in the chapter) if a computerized accounting system is being used or into the Cash Receipts journal if the books are being kept manually.

Practice: Proving Out

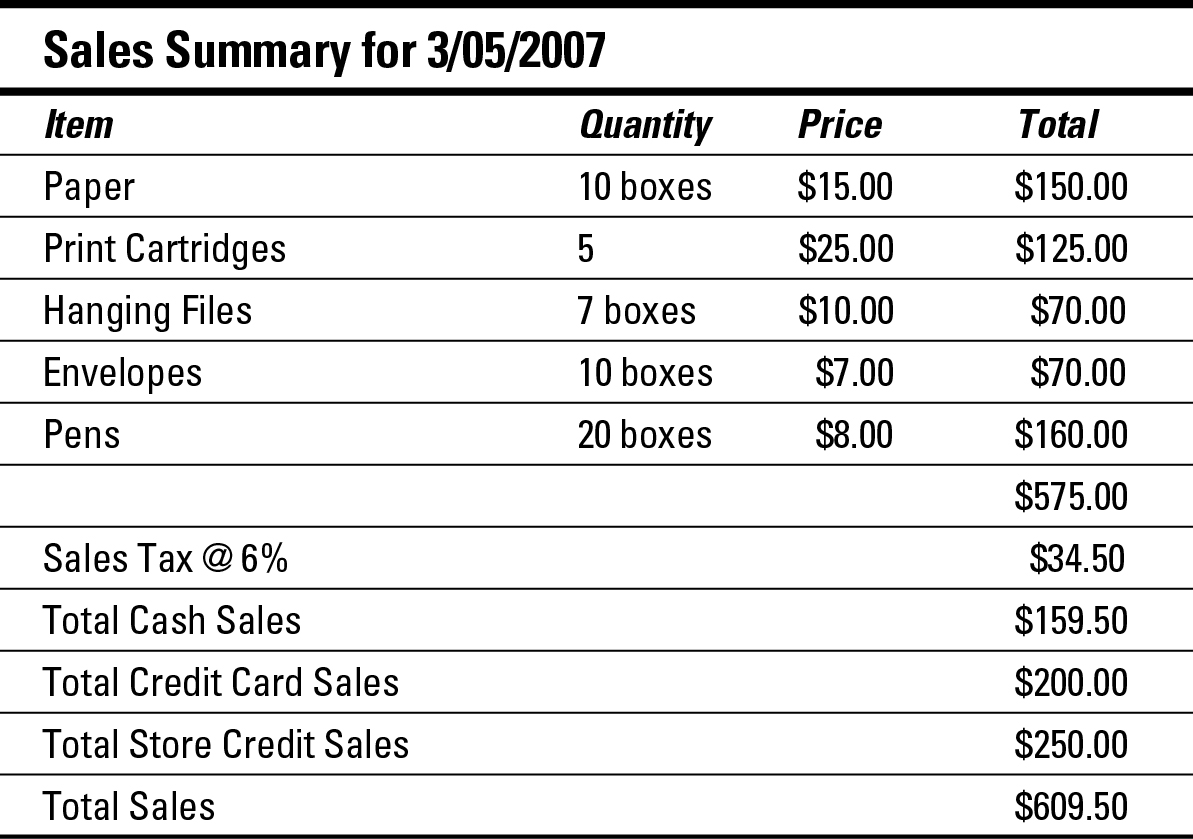

Q. Suppose you began the day with $100 in the register and ended the day with $264.50 in the register. Is the ending cash total in the following cash summary correct?

A. Complete the following cash-out form:

Cash Register: Sales Summary Date: 3/5/2011

|

Receipts |

Sales |

Cash in Register |

|

Beginning Cash |

$100.00 |

|

|

Cash Sales |

$159.50 |

|

|

Credit Card Sales |

$200.00 |

|

|

Store Credit Sales |

$250.00 |

|

|

Total Sales |

$609.50 |

|

|

Minus Sales on Credit |

($450.00) |

|

|

Total Cash Received |

$159.50 |

|

|

Total Cash that Should be in Register |

$259.50 |

|

|

Actual Cash in Register |

$264.50 |

|

|

Difference |

Overage of $5.00 |

So in this example, with the cash remaining in the cash register, the cashier actually took in $5 more than needed, most likely from an error in giving change.

5. Suppose the cash register had $100 at the beginning of the day and $316.10 at the end of the day. Use the following cash register summary to fill out the blank cash-out form and determine whether the ending cash total in the summary is correct.

Solve It

Cash Register: Sales Summary Date: 3/15/2011

|

Receipts |

Sales |

Cash in Register |

|

Beginning Cash |

_____ |

_____ |

|

Cash Sales |

_____ |

_____ |

|

Credit Card Sales |

_____ |

_____ |

|

Store Credit Sales |

_____ |

_____ |

|

Total Sales |

_____ |

_____ |

|

Minus Sales on Credit |

_____ |

_____ |

|

Total Cash Received |

_____ |

_____ |

|

Total Cash that Should Be in Register |

_____ |

|

|

Actual Cash in Register |

_____ |

|

|

Difference |

_____ |

Tracking Sales Discounts

Most business offer discounts at some point in time to generate more sales. Discounts are usually in the form of a sale with 10 percent, 20 percent, or even more off purchases.

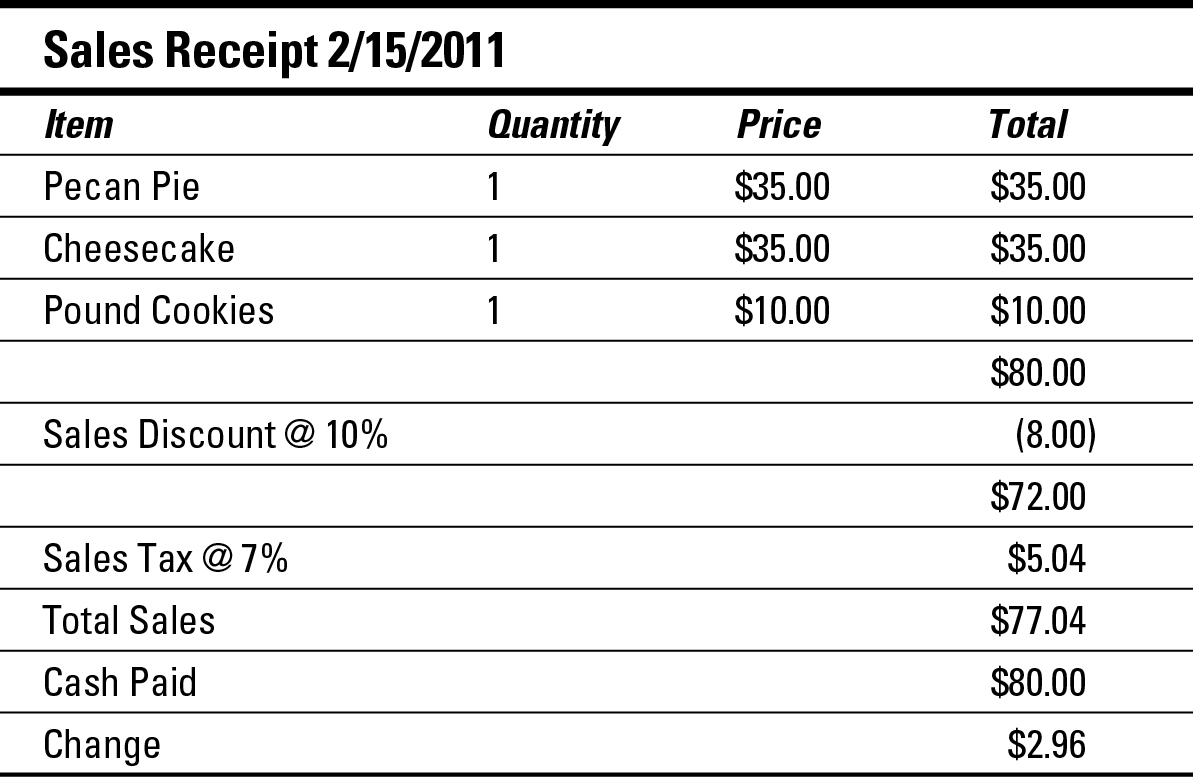

When you offer discounts to customers, it’s a good idea to track your sales dis-counts in a separate account so that you can keep an eye on how much you discount sales in each month. If you find you’re losing more and more money to discounting, look closely at your pricing structure and competition to find out why you frequently need to lower your prices to make sales. You can track discount information very easily by using the data found on a standard sales register receipt. The following receipt from a bakery includes sales discount details.

From this example, you can see clearly that stores take in less cash when offering discounts. When recording the sale in the Cash Receipts journal, you record the discount as a debit. This debit increases the Sales Discount account, which is subtracted from the Sales account to calculate the Net Sales. (I walk you through all these steps and calculations when I discuss preparing the income statement in Chapter 19.) Here’s what the bakery’s entry for this particular sale looks like in the Cash Receipts journal:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Cash in Checking |

$76.32 |

|

|

Sales Discounts |

$8.00 |

|

|

Sales |

$80.00 |

|

|

Sales Tax Collected |

$4.32 |

|

|

Cash receipts for 4/25/2011 |

||

Practice: Recording Discounts

Q. How do you record the following sales transaction?

A. Here’s what the bookkeeping entry looks like:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Cash in Checking |

$77.04 |

|

|

Sales Discount |

$8.00 |

|

|

Sales |

$80.00 |

|

|

Sales Tax Collected |

$5.04 |

|

|

Cash receipts for 2/15/2011 |

||

Note that in this situation, the Cash in Checking amount is actually less than the sales amount to compensate for the lost revenue for the sales discount. Yet when you total the debit and credit entries, they’re equal — both total to $85.04.

6. How do you record the following transaction in your books?

Solve It

7. How do you record the following credit transaction in your books?

Solve It

Recording Sales Returns and Allowances

Most stores deal with sales returns on a regular basis. Customers commonly return items they’ve purchased because the item is defective, because they’ve changed their minds, or for any other reason. Instituting a no-return policy is guaranteed to produce very unhappy customers, so to maintain good customer relations, you should allow sales returns.

Sales allowances (sales incentive programs) are becoming more popular with businesses. Sales allowances are most often in the form of a gift card. A gift card that’s sold is actually a liability for the company because the company has received cash, but no merchandise has gone out; therefore, the company has to keep track of how much is yet to be sold without receiving additional cash. For that reason, gift card sales are entered in a Gift Card liability account. When a customer makes a purchase at a later date with the gift card, the Gift Card liability account is reduced by the purchase amount.

Accepting sales returns can be a more complicated process than accepting sales allowances. Usually, a business posts a set of rules for returns that may include stipulations like the following:

Returns are only allowed within 30 days of purchase.

Returns are only allowed within 30 days of purchase.

You must have a receipt to return an item.

You must have a receipt to return an item.

If you return an item without a receipt, you can receive only store credit.

If you return an item without a receipt, you can receive only store credit.

You use the information collected by the cashier who handled the return to input the sales return data into the books. For example, if a customer returns a $40 item that was purchased with cash, you record the cash refund in the Cash Receipts Journal like this:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Sales Returns and Allowances |

$40.00 |

|

|

Sales Taxes Collected @ 6% |

$2.40 |

|

|

Cash in Checking |

$42.40 |

|

|

To record return of purchase, 4/30/2011 |

||

In this journal entry,

The Sales Returns and Allowances account increases. This account normally carries a debit balance and is subtracted from Sales when preparing the income statement, thereby reducing revenue received from customers.

The Sales Returns and Allowances account increases. This account normally carries a debit balance and is subtracted from Sales when preparing the income statement, thereby reducing revenue received from customers.

The debit to the Sales Tax Collected account reduces the amount in that account because sales tax is no longer due on the purchase.

The debit to the Sales Tax Collected account reduces the amount in that account because sales tax is no longer due on the purchase.

The credit to the Cash in Checking account reduces the amount of cash in that account.

The credit to the Cash in Checking account reduces the amount of cash in that account.

Practice: Tracking Sales Returns and Allowances

Q. A customer returns a blouse she bought with cash for $40. She has a receipt showing when she made the original purchase; the sales tax is 6 percent. How do you record that transaction in the books?

A. Here’s how you record the transaction:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Sales Returns and Allowances |

$40.00 |

|

|

Sales Taxes Collected |

$2.40 |

|

|

Cash in Checking |

$42.40 |

8. A customer returns a pair of pants he bought on a credit card for $35. He has a receipt showing when he made the original purchase; the sales tax is 6 percent. How do you record that transaction in the books?

Solve It

9. A customer returns a toy she bought with cash for $25. She has a receipt for the purchase; the sales tax is 6 percent. How do you record that transaction in the books?

Solve It

Monitoring Accounts Receivable

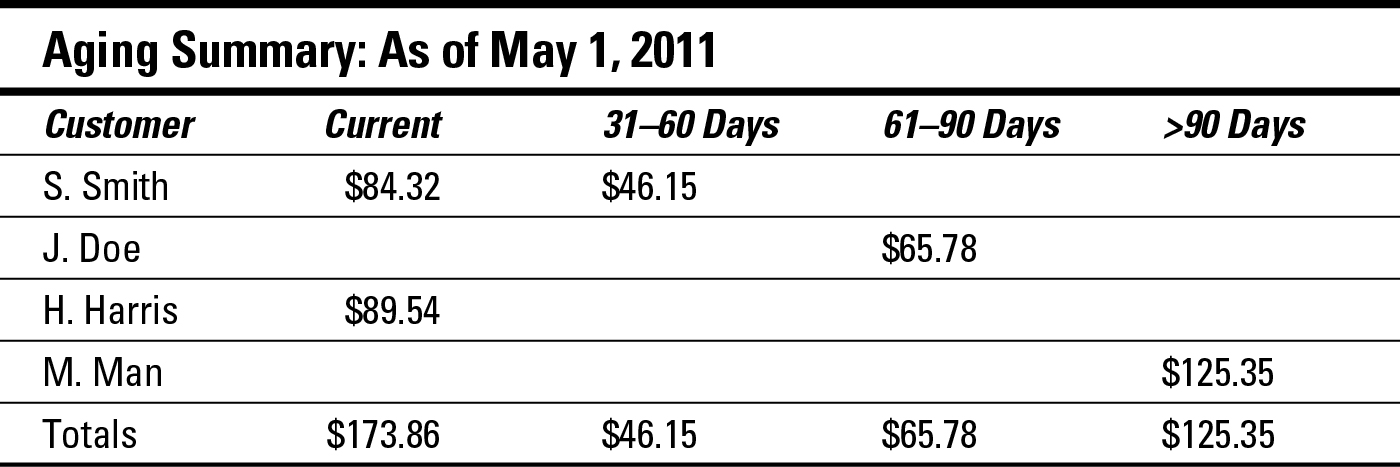

Making sure customers pay their bills is a crucial responsibility of the bookkeeper. Before sending out the monthly bills, you should prepare an Aging Summary Report that lists all customers who owe money to the company and how old each debt is. If you keep the books manually, you collect the necessary information from each customer account. If you keep the books in a computerized accounting system, you can generate this report automatically. Either way, your Aging Summary Report should look similar to this example report:

The Aging Summary quickly tells you which customers are behind in their bills. In the case of this example, customers are cut off from future purchases when their payments are more than 60 days late, so J. Doe and M. Man aren’t able to buy on store credit until their bills are paid in full.

Practice: Aging Summary

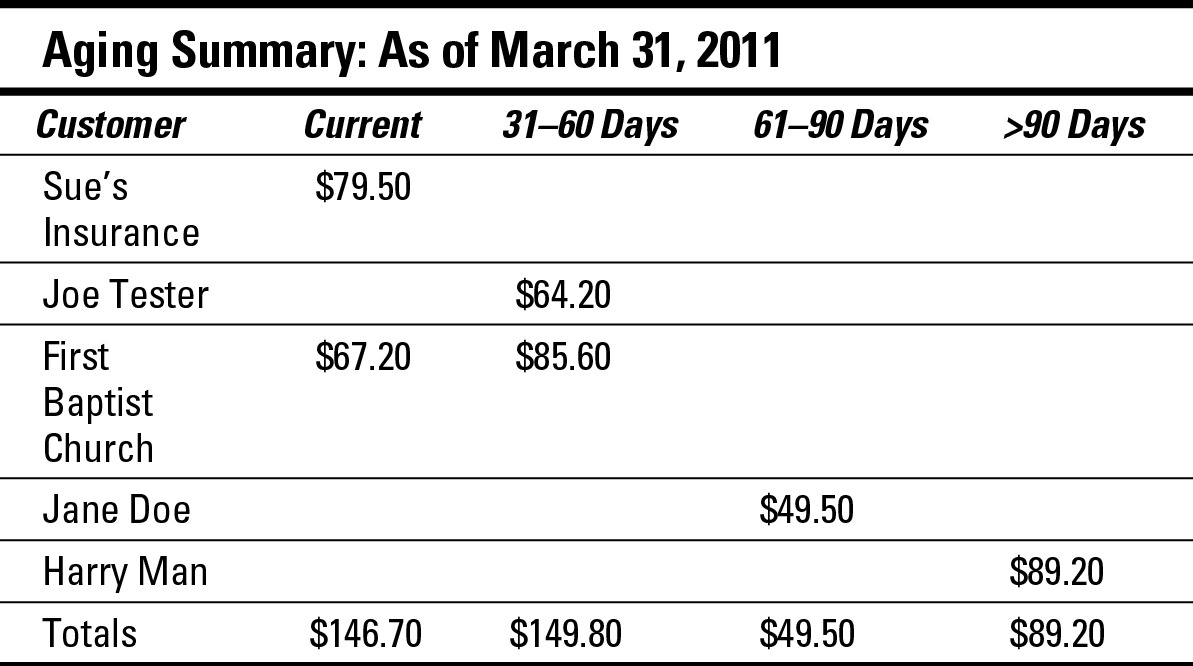

Q. The following list shows five customers who bought on credit from the office supply store and had not yet paid their bills as of 3/31/2011. Prepare an Aging Summary report as of March 31 for all outstanding customer accounts.

|

Customer |

Date of Purchase |

Amount Purchased |

|

Sue’s Insurance Company |

3/5/2011 |

$79.50 |

|

Joe Tester |

2/25/2011 |

$64.20 |

|

First Baptist Church |

2/15/2011 |

$85.60 |

|

3/15/2011 |

$67.20 |

|

|

Jane Doe |

1/15/2011 |

$49.50 |

|

Harry Man |

12/23/2011 |

$89.20 |

A. Here’s what the Aging Summary report looks like:

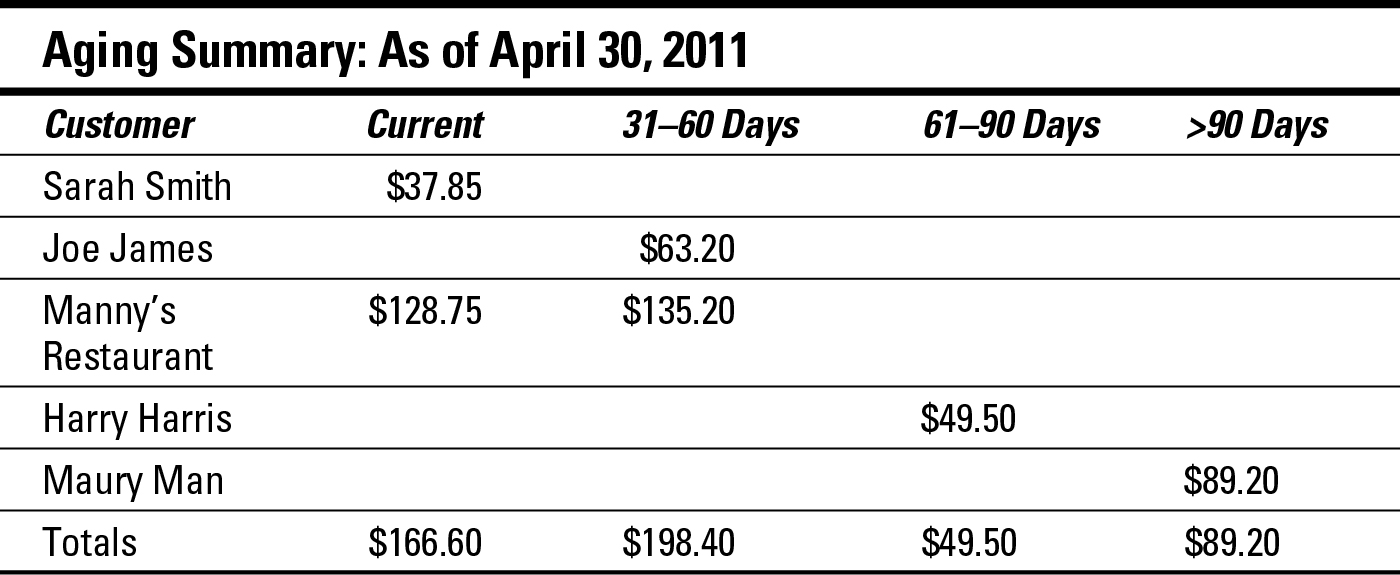

10. Use the information from the following account list to set up an Aging Summary as of 4/30/2011:

|

Customer |

Date of Purchase |

Amount Purchased |

|

Sarah Smith |

4/5/2011 |

$37.85 |

|

Joe James |

3/15/2011 |

$63.20 |

|

Manny’s Restaurant |

3/20/2011 |

$135.20 |

|

4/15/2011 |

$128.75 |

|

|

Harry Harris |

2/25/2011 |

$49.50 |

|

Maury Man |

1/5/2011 |

$89.20 |

Solve It

Accepting Your Losses

You may encounter a situation in which your business never gets paid by a customer, even after an aggressive collections process. In this case, you have no choice but to write off the purchase as a bad debt and accept the loss.

Most businesses review their Aging Reports every 6 to 12 months and decide which accounts need to be written off as bad debt. Accounts written off are tracked in a General Ledger account called Bad Debt. (See Chapter 4 for more information about the General Ledger.) The Bad Debt account appears as an expense account on the income statement. When you write off a customer’s account as bad debt, the Bad Debt account increases, and the Accounts Receivable account decreases.

To give you an idea of how you write off an account, assume that a customer never pays the $105.75 it owes. Here’s what your journal entry looks like for this debt:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Bad Debt |

$105.75 |

|

|

Accounts Receivable |

$105.75 |

In a computerized accounting system, you enter the information by using a customer payment form and allocate the amount due to the Bad Debt expense account.

Answers to Counting Your Sales

1 Here’s what the transaction entry looks like:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Cash in Checking |

$64.20 |

|

|

Sales |

$60.00 |

|

|

Sales Tax Collected |

$4.20 |

|

|

Cash receipts for 2/25/2011 |

||

2 Here’s what the transaction entry looks like:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Cash in Checking |

$79.50 |

|

|

Sales |

$75.00 |

|

|

Sales Tax Collected |

$4.50 |

|

|

Cash receipts for 3/5/2011 |

||

3 Here’s what the transaction entry looks like:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Accounts Receivable |

$64.20 |

|

|

Sales |

$60.00 |

|

|

Sales Tax Collected |

$4.20 |

|

|

Credit receipts for 2/25/2011 |

||

4 Here’s what the transaction entry looks like:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Accounts Receivable |

$79.50 |

|

|

Sales |

$75.00 |

|

|

Sales Tax Collected |

$4.50 |

|

|

Credit receipts for 3/5/2011 |

||

5 Here’s how you complete the cash out form.

Cash Register: Jane Doe Date: 3/15/2011

|

Receipts |

Sales |

Cash in Register |

|

Beginning Cash |

$100.00 |

|

|

Cash Sales |

$226.80 |

|

|

Credit Card Sales |

$200.00 |

|

|

Store Credit Sales |

$400.00 |

|

|

Total Sales |

$826.80 |

|

|

Minus Sales on Credit |

$600.00 |

|

|

Total Cash Received |

$226.80 |

|

|

Total Cash that Should be in Register |

$326.80 |

|

|

Actual Cash in Register |

$316.10 |

|

|

Difference |

Shortage of $10.70 |

6 Here’s what the transaction entry looks like:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Cash in Checking |

$63.60 |

|

|

Sales Discount |

$15.00 |

|

|

Sales |

$75.00 |

|

|

Sales Tax Collected |

$3.60 |

|

|

Cash receipts for 3/5/2011 |

7 Here’s what the transaction entry looks like:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Cash in Checking |

$312.60 |

|

|

Accounts Receivable |

$175.00 |

|

|

Sales Discount |

$115.00 |

|

|

Sales |

$575.00 |

|

|

Sales Tax Collected |

$27.60 |

|

|

Cash receipts for 3/5/2011 |

||

8 Here’s what the transaction entry looks like:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Sales Returns and Allowances |

$35.00 |

|

|

Sales Taxes Collected |

$2.10 |

|

|

Cash in Checking |

$37.10 |

Even though the customer is receiving a credit on his credit card, you show this refund by crediting your “Cash in Checking” account. Remember that when a customer uses a credit card, the card is processed by the bank and cash is deposited in the store’s checking account.

9 Here’s what the transaction entry looks like:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Sales Returns and Allowances |

$25.00 |

|

|

Sales Taxes Collected |

$1.50 |

|

|

Cash in Checking |

$26.50 |

10 Here’s what the Aging Summary report looks like:

The only type of payment that doesn’t fall under the umbrella of a cash payment is purchases made on store credit. And by

The only type of payment that doesn’t fall under the umbrella of a cash payment is purchases made on store credit. And by  If you’re using a computerized accounting system, you can enter more detail from the day’s receipts and track inventory sold as well. Most of the computerized accounting systems do include the ability to track the sale of inventory. Figure 9-1 shows you the QuickBooks Sales receipt form that you can use to input data from each day’s sales.

If you’re using a computerized accounting system, you can enter more detail from the day’s receipts and track inventory sold as well. Most of the computerized accounting systems do include the ability to track the sale of inventory. Figure 9-1 shows you the QuickBooks Sales receipt form that you can use to input data from each day’s sales. If your company accepts credit cards, expect sales revenue to be reduced by the fees paid to credit-card companies. Usually, you face monthly fees as well as fees per transaction; however, each company sets up individual arrangements with its bank regarding these fees. Sales volume impacts how much you pay in fees, so when researching bank services, be sure to compare credit card transaction fees to find a good deal.

If your company accepts credit cards, expect sales revenue to be reduced by the fees paid to credit-card companies. Usually, you face monthly fees as well as fees per transaction; however, each company sets up individual arrangements with its bank regarding these fees. Sales volume impacts how much you pay in fees, so when researching bank services, be sure to compare credit card transaction fees to find a good deal.