Solve It

Chapter 10

Employee Payroll and Benefits

In This Chapter

Planning for your pay structure

Planning for your pay structure

Figuring net pay and collecting and depositing employee taxes

Figuring net pay and collecting and depositing employee taxes

Keeping track of benefits

Keeping track of benefits

Preparing and recording payroll

Preparing and recording payroll

Finding new ways to deal with payroll responsibilities

Finding new ways to deal with payroll responsibilities

Unless your business has only one employee (you, the owner), you’ll most likely hire employees, and that means you’ll have to pay them, offer benefits, and manage a payroll.

Responsibilities for hiring and paying employees usually are shared between the human resources staff and the bookkeeping staff. As the bookkeeper, you must be sure that all government tax-related forms are completed and handle all payroll responsibilities, including paying employees, collecting and paying employee taxes, collecting and managing employee benefit contributions, and paying benefit providers. This chapter examines the various employee staffing issues that bookkeepers need to be able to manage.

Setting the Stage for Staffing: Making Payroll Decisions

After you decide that you want to hire employees for your business, you must be ready to deal with a lot of government paperwork. In addition to paperwork, you face many decisions about how to pay employees and who will be responsible for maintaining the paperwork required by state, local, and federal government entities.

Knowing what needs to be done to satisfy government bureaucracies isn’t the only issue you must consider before the first person is hired; you also must decide how frequently you will pay employees and what type of wage and salary scales you want to set up.

Completing government forms

Even before you hire your first employee, you need to start filing government forms related to hiring. If you plan to hire staff, you must first apply for an Employer Identification Number, or EIN. Government entities use this number to track your employees, the money you pay them, and any taxes collected and paid on their behalf.

Before employees start working for you, they must fill out forms, including the W-4 (tax withholding form), I-9 (citizenship verification form), and W-5 (for employees eligible for the Earned Income Credit). The following sections explain each of these forms as well as the EIN.

Employer Identification Number (EIN)

Every company must have an EIN to hire employees. If your company is incorporated, which means you’ve filed paperwork with the state and become a separate legal entity, you already have an EIN. (See Chapter 21 for the lowdown on corporations and other business types.) Otherwise, you must complete and submit Form SS-4 to get an EIN.

In addition to tracking pay and taxes, state entities use the EIN number to track the payment of unemployment taxes and workers’ compensation taxes, both of which the employer must pay. I talk more about them in Chapter 11.

W-4

Every person you hire must fill out a W-4 form called the “Employee’s Withholding Allowance Certificate.” You’ve probably filled out a W-4 at least once in your life if you’ve ever worked for someone else. You can download this form and make copies for your employees at www.irs.gov/pub/ irs-pdf/fw4.pdf.

This form tells you, the employer, how much to take out of your employees’ paychecks in income taxes. On the W-4, employees indicate whether they’re married or single. They can also claim additional allowances if they have children or other major deductions that can reduce their tax bills. The amount of income taxes you need to take out of each employee’s check depends on how many allowances he or she claimed on the W-4.

An employee can always fill out a new W-4 to reflect life changes that impact tax deductions. For example, if the employee was single when he started working for you and gets married a year later, he can fill out a new W-4 and claim his spouse, lowering the amount of taxes that must be deducted from his check. Another common life change that can reduce an employee’s tax deduction is the birth or adoption of a baby.

I-9

All employers in the United States must verify that any person they intend to hire is a U.S. citizen or has the right to work in the United States. As an employer, you verify this information by completing and keeping on file an I-9 form from the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). The new hire fills out Section 1 of the form by providing information about his name and address, birth history, Social Security number, and U.S. Citizenship or work permit.

You then fill out Section 2, which requires you to check for and copy documents that establish identity and prove employment eligibility. For a new hire who’s a U.S. citizen, you make a copy of one picture ID (usually a driver’s license but maybe a military ID, student ID, or other state ID) and an ID that proves work eligibility, such as a Social Security card, birth certificate, or citizen ID card. A U.S. passport can serve as both a picture ID and proof of employment eligibility. Instructions provided with the form list all acceptable documents you can use to verify work eligibility.

You can download the form and its instructions from the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Web site at www.uscis.gov/files/form/i-9.pdf.

W-5

Some employees you hire may be eligible for the Earned Income Credit (EIC), which is a tax credit that refunds some of the money the employee would otherwise pay in taxes such as Social Security or Medicare. In order to get this credit, the employee must have a child and meet other income qualifications that are detailed on the form’s instructions.

The government started the EIC, which reduces the amount of tax owed, to help lower-income people offset increases in living expenses and Social Security taxes. Having an employee complete Form W-5 allows you to advance the expected savings of the EIC to the employee on his paycheck each pay period rather than make him wait to get the money back at the end of the year after filing tax forms. The advance amount isn’t considered income, so you don’t need to take taxes out on this amount.

As an employer, you aren’t required to verify an employee’s eligibility for the EIC. The eligible employee must complete a W-5 each year to indicate that he still qualifies for the credit. If the employee doesn’t file the form with you, you can’t advance any money to him. If an employee qualifies for the EIC, you calculate his paycheck the same as you would any other employee’s paycheck, deducting all necessary taxes to get the employee’s net pay. Then you add back in the EIC advance credit that’s allowed.

Any advance money you pay to the employee can be subtracted from the employee taxes you owe to the government. For example, if you’ve taken out $10,000 from employees’ checks to pay their income, Social Security taxes, and Medicare taxes and then returned $500 to employees who qualified for the EIC, you subtract that $500 from the $10,000 and pay the government only $9,500.

You can download this form and its instructions at www.irs.gov/pub/ irs-prior/fw5--2009.pdf.

Picking pay periods

Deciding how frequently you’ll pay employees is an important point to work out before hiring staff. Most businesses chose one or more of these four pay periods:

Weekly: Employees are paid every week, and payroll must be done 52 times a year.

Weekly: Employees are paid every week, and payroll must be done 52 times a year.

Biweekly: Employees are paid every two weeks, and payroll must be done 26 times a year.

Biweekly: Employees are paid every two weeks, and payroll must be done 26 times a year.

Semimonthly: Employees are paid twice a month, commonly on the 15th and the last day of the month, and payroll must be done 24 times a year.

Semimonthly: Employees are paid twice a month, commonly on the 15th and the last day of the month, and payroll must be done 24 times a year.

Monthly: Employees are paid once a month, and payroll must be done 12 times a year.

Monthly: Employees are paid once a month, and payroll must be done 12 times a year.

You can choose to use any of these pay periods, and you may even decide to use more than one type. For example, some companies will pay hourly employees (employees paid by the hour) weekly or biweekly and pay salaried employees (employees paid by a set salary regardless of how many hours they work) semimonthly or monthly. Whatever your choice, decide on a consistent pay period policy and be sure to make it clear to employees when they’re hired.

Determining wage and salary types

You have a lot of leeway regarding the level of wages and salary you pay your employees, but you still have to follow the rules laid out by the U.S. Department of Labor. When deciding on wages and salaries, you have to first categorize your employees. Employees fall into one of two categories:

Exempt employees are exempt from the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), which sets rules for minimum wage, equal pay, overtime pay, and child labor laws. Executives, administrative personnel, managers, professionals, computer specialists, and outside salespeople can all be exempt employees. They’re normally paid a certain amount per pay period with no connection to the number of hours worked. Often, exempt employees work well over 40 hours per week without extra pay. Prior to new rules from the Department of Labor effective in 2004, only high-paid employees fell in this category; today, however, employees making as little as $23,660 can be placed in the exempt category.

Exempt employees are exempt from the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), which sets rules for minimum wage, equal pay, overtime pay, and child labor laws. Executives, administrative personnel, managers, professionals, computer specialists, and outside salespeople can all be exempt employees. They’re normally paid a certain amount per pay period with no connection to the number of hours worked. Often, exempt employees work well over 40 hours per week without extra pay. Prior to new rules from the Department of Labor effective in 2004, only high-paid employees fell in this category; today, however, employees making as little as $23,660 can be placed in the exempt category.

Nonexempt employees must be hired according to rules of the FLSA, meaning that companies with gross sales of over $500,000 per year must pay a minimum wage per hour of $7.25. Smaller companies must comply with minimum wage rules if they engage in interstate commerce or in the production of goods for commerce, such as having employees who work in transportation or communications or who regularly use the mail or telephones for interstate communications.

Nonexempt employees must be hired according to rules of the FLSA, meaning that companies with gross sales of over $500,000 per year must pay a minimum wage per hour of $7.25. Smaller companies must comply with minimum wage rules if they engage in interstate commerce or in the production of goods for commerce, such as having employees who work in transportation or communications or who regularly use the mail or telephones for interstate communications.

For new employees who are under the age of 20 and need training, an employer can pay as little as $4.25 for the first 90 days. Also, any nonexempt employee who works over 40 hours in a seven-day period must be paid time and one-half for the additional hours. Minimum wage doesn’t have to be paid in cash. The employer can pay some or all of the wage in room and board provided it doesn’t make a profit on any non-cash payments. Also, the employer can’t charge the employee to use its facilities if the employee’s use of a facility is primarily for the employer’s benefit.

The federal government adjusted the minimum wage law in 2009. Some states do have higher minimum wage laws, so be sure to check with your state department of labor to be certain you’re meeting state wage guidelines. You can get a quick overview of states with higher minimum wage rates at www.dol.gov/whd/minwage/america.htm.

Collecting Employee Taxes

In addition to following wage and salary guidelines set for your business (see the earlier section “Setting the Stage for Staffing: Making Payroll Decisions”), you, the bookkeeper, must also be familiar with how to calculate the employee taxes that must be deducted from each employee’s paycheck when calculating payroll. These taxes include Social Security; Medicare; and federal, state, and local withholding taxes.

Sorting out Social Security tax

Employers and employees share the Social Security tax equally: Each must pay 6.2 percent (0.062) toward Social Security up to a cap of $106,800 per year per person (as of this writing). After an employee earns $106,800, no additional Social Security taxes are taken out of his check. The federal government adjusts the cap each year based on salary level changes in the marketplace. Essentially, the cap gradually increases as salaries increase.

The calculation for Social Security taxes is relatively simple. For example, for an employee who makes $1,000 per pay period, you calculate Social Security tax this way:

$1,000 × 0.062 = $62

The bookkeeper deducts $62 from this employee’s gross pay, and the company pays the employer’s share of $62. Thus, the total amount submitted in Social Security taxes for this employee is $124.

Note: A temporary 2-percent Social Security tax cut for workers was approved as part of a short-term stimulus package for 2011. That means in 2011, the employee side of Social Security was just 4.2 percent rather than 6.2 percent. Whether this reduction will be extended beyond 2011 is still up in the air as I write this book.

Making sense of Medicare tax

Employees and employers also share Medicare taxes, which are 1.45 percent each. However, unlike Social Security taxes, the federal government places no cap on the amount that must be paid in Medicare taxes. So even if someone makes $1 million per year, 1.45 percent is calculated for each pay period and paid by both the employee and the employer. Here’s an example of how you calculate the Medicare tax for an employee who makes $1,000 per pay period:

$1,000 × 0.0145 = $14.50

The bookkeeper deducts $14.50 from this employee’s gross pay, and the company pays the employer’s share of $14.50. Thus, the total amount submitted in Medicare taxes for this employee is $29.

Figuring out federal withholding tax

Deducting federal withholding taxes is a much more complex task for bookkeepers than deducting Social Security or Medicare taxes. Not only do you have to worry about an employee’s tax rate, but you also must consider the number of withholding allowances the employee claimed on her W-4 and whether she’s married or single. For example, the first $8,500 of an unmarried person’s income (the first $17,000 for a married couple filing jointly) is taxed at 10 percent. Other tax rates depending on income are 15 percent, 25 percent, 28 percent, 33 percent, and 35 percent.

Trying to figure out taxes separately for each employee based on his or her tax rate and number of allowances would be an extremely time-consuming task, but luckily, you don’t have to do that. The IRS publishes tax tables in Publication 15, Employer’s Tax Guide, that let you just look up an employee’s tax obligation based on the taxable salary and withholdings. You can access the IRS Employer’s Tax Guide online at www.irs.gov/publications/p15/index.html. You can find the links to income tax withholding tables in Chapter 16 of the online version of Publication 15.

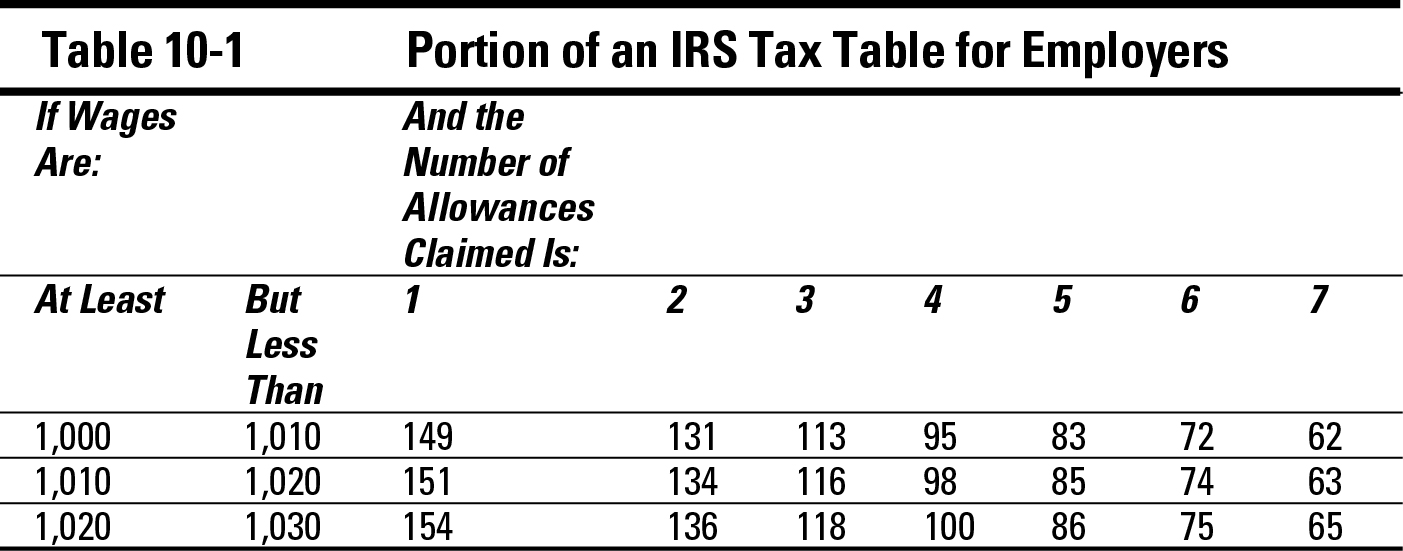

The IRS’s tax tables give you detailed numbers up to ten withholding allowances. Table 10-1 shows a sample tax table with only seven allowances because of space limitations. But even with seven allowances, you get the idea — just match the employee’s wage range with the number of allowances he or she claims, and the box where they meet contains the amount of that employee’s tax obligation. For example, if you’re preparing a paycheck for an employee whose taxable income is $1,000 per pay period, and he claims three withholding allowances — one for himself, one for his wife, and one for his children — the amount of federal income taxes you deduct from his pay is $113.

Settling up state and local withholding taxes

In addition to the federal government, most states have income taxes, and some cities even have local income taxes. You can find all state tax rates and forms online at www.payroll-taxes.com/PayrollTaxes/00000103.htm. If your state or city has income taxes, they need to be taken out of each employee’s paycheck.

Determining Net Pay

Net pay is the amount a person is paid after subtracting all tax and benefit deductions. In other words after all deductions are subtracted from a person’s gross pay, you’re left with the net pay.

After you figure out all the necessary taxes to be taken from an employee’s paycheck, you can calculate the check amount. Here’s the equation and an example of how you calculate the net pay amount:

Gross pay – (Social Security + Medicare + Federal withholding tax + State withholding tax + Local withholding tax) = Net pay

1,000 – (62 + 14.50 + 148 + 45 + 0) = 730.50

Practice: Payroll Tax Calculations

Q. Mary earns $1,000 per week and claims one withholding deduction. Calculate her Social Security, Medicare, and federal withholding taxes. Then calculate her paycheck after taxes have been taken out. (Use Table 10-1 earlier in the chapter.)

A. Here’s how Mary’s calculations work out:

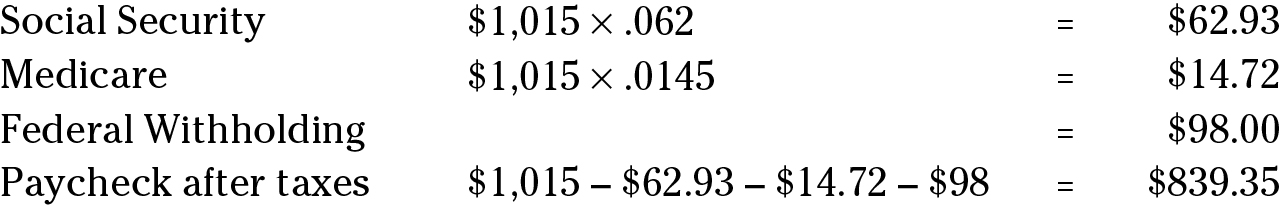

1. Carl earns $1,015 per week and claims four withholding deductions. Calculate his Social Security, Medicare, and federal withholding taxes. Then calculate his paycheck after taxes have been taken out. (Use Table 10-1 earlier in the chapter.)

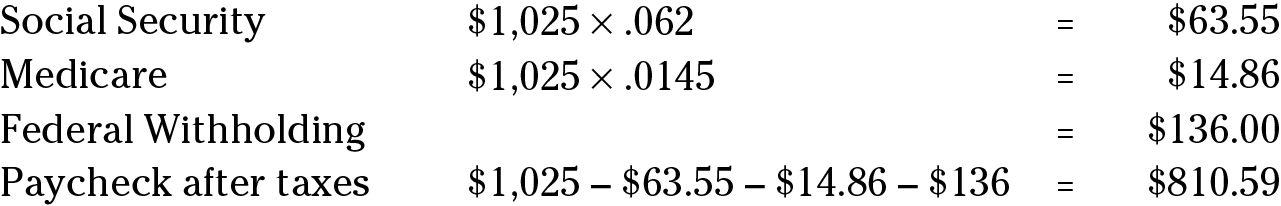

2. Karen earns $1,025 per week and claims two withholding deductions. Calculate her Social Security, Medicare, and federal withholding taxes. Then calculate her paycheck after taxes have been taken out. (Use Table 10-1 earlier in the chapter.)

Solve It

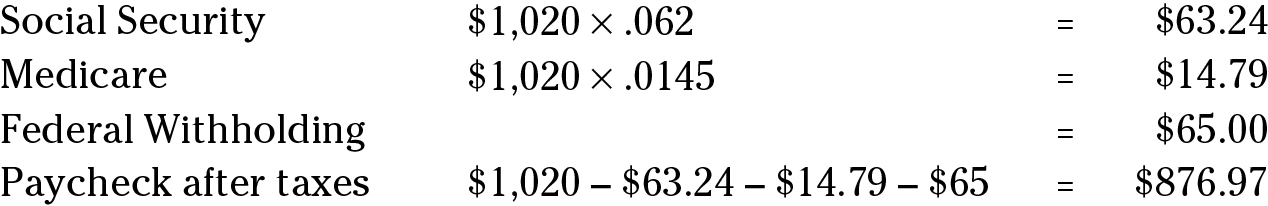

3. Tom earns $1,020 per week and claims seven withholding deductions. Calculate his Social Security, Medicare, and federal withholding taxes. Then calculate his paycheck after taxes have been taken out. (Use Table 10-1 earlier in the chapter.)

Solve It

Surveying Your Benefits Options

Benefits include programs that you provide your employees to better their lives, such as health insurance and retirement savings opportunities. Most benefits are tax-exempt, which means that the employee isn’t taxed for them. However, some benefits are taxable, so the employee has to pay taxes on the money or the value of the benefits received. This section reviews the different tax-exempt and taxable benefits you can offer your employees.

Tax-exempt benefits

Most benefits are tax-exempt, or not taxed. Health care and retirement benefits are the most common of this type of benefit. In fact, accident and health benefits and retirement benefits make up the largest share of employers’ pay toward employees’ benefits. Luckily, not only are these benefits tax-exempt, but anything an employee pays toward them can also be deducted from the gross pay, so the employee doesn’t have to pay taxes on that part of his salary or wage.

For example, if an employee’s share of health insurance is $50 per pay period and he makes $1,000 per pay period, his taxable income is actually $1,000 minus the $50 health insurance premium contribution, or $950. As the bookkeeper, you calculate taxes on $950 rather than $1,000 in this situation.

The money that an employee contributes to the retirement plan you offer is tax deductible, too. For example, if an employee contributes $50 per pay period to your company’s 401(k) retirement plan, that $50 can also be subtracted from the employee’s gross pay before you calculate net pay. So if an employee contributes $50 to both health insurance and retirement, the $1,000 taxable pay is reduced to only $900 taxable pay. (According to the tax table for that pay level, his federal withholding taxes are only $123, a savings of $25 over a taxable income of $1,000, or 25 percent of his health and retirement costs. Not bad.)

You can offer myriad other tax-exempt benefits to employees, as well, including

Adoption assistance: You can provide up to $13,170 per child that an employee plans to adopt without having to include that amount in gross income for the purposes of calculating federal withholding taxes. The value of this benefit must be included when calculating Social Security and Medicare taxes, however.

Adoption assistance: You can provide up to $13,170 per child that an employee plans to adopt without having to include that amount in gross income for the purposes of calculating federal withholding taxes. The value of this benefit must be included when calculating Social Security and Medicare taxes, however.

Athletic facilities: You can offer your employees the use of a gym on premises your company owns or leases without having to include the value of the gym facilities in gross pay. In order for this benefit to qualify as tax-exempt, the facility must be operated by the company primarily for the use of employees, their spouses, and their dependent children.

Athletic facilities: You can offer your employees the use of a gym on premises your company owns or leases without having to include the value of the gym facilities in gross pay. In order for this benefit to qualify as tax-exempt, the facility must be operated by the company primarily for the use of employees, their spouses, and their dependent children.

Dependent care assistance: You can help your employees with dependent care expenses, which can include children and elderly parents, provided you offer the benefit to make it possible for the employee to work.

Dependent care assistance: You can help your employees with dependent care expenses, which can include children and elderly parents, provided you offer the benefit to make it possible for the employee to work.

Education assistance: You can pay employees’ educational expenses up to $5,250 without having to include that payment in gross income.

Education assistance: You can pay employees’ educational expenses up to $5,250 without having to include that payment in gross income.

Employee discounts: You can offer employees discounts on the company’s products without including the value of the discounts in their gross pay, provided the discount isn’t more than 20 percent less than what’s charged to customers. If you only offer this discount to high-paid employees, the value of these discounts must be included in gross pay of those employees.

Employee discounts: You can offer employees discounts on the company’s products without including the value of the discounts in their gross pay, provided the discount isn’t more than 20 percent less than what’s charged to customers. If you only offer this discount to high-paid employees, the value of these discounts must be included in gross pay of those employees.

Group term life insurance: You can provide group term life insurance up to a coverage level of $50,000 to your employees without including the value of this insurance in their gross pay. Premiums for coverage above $50,000 must be added to calculations for Social Security and Medicare taxes.

Group term life insurance: You can provide group term life insurance up to a coverage level of $50,000 to your employees without including the value of this insurance in their gross pay. Premiums for coverage above $50,000 must be added to calculations for Social Security and Medicare taxes.

Meals: Meals that have little value (such as coffee and doughnuts) don’t have to be reported as taxable income. Also, occasional meals brought in so employees can work late also don’t have to be reported in employees’ income.

Meals: Meals that have little value (such as coffee and doughnuts) don’t have to be reported as taxable income. Also, occasional meals brought in so employees can work late also don’t have to be reported in employees’ income.

Moving expense reimbursements: If you pay moving expenses for employees, you don’t have to report these reimbursements as employee income as long as the reimbursements are for items that would qualify as tax-deductible moving expenses on an employee’s individual tax return. Employees who have been reimbursed by their employers can’t deduct the moving expenses that the employer paid.

Moving expense reimbursements: If you pay moving expenses for employees, you don’t have to report these reimbursements as employee income as long as the reimbursements are for items that would qualify as tax-deductible moving expenses on an employee’s individual tax return. Employees who have been reimbursed by their employers can’t deduct the moving expenses that the employer paid.

Taxable benefits

You may decide to provide some benefits that are taxable. These include the personal use of a company automobile, life insurance premiums for coverage over $50,000, and benefits that exceed allowable maximums. For example, if you pay $10,250 toward an employee’s education expenses, $5,000 of that amount must be reported as income because the federal government’s cap is $5,250.

Dealing with cafeteria plans

No, I’m not talking about offering a lunch spot for your employees. Cafeteria plans are benefit plans that offer employees a choice of benefits based on cost. Employees can pick and choose from those benefits and put together a benefit package that works best for them within the established cost structure.

For example, a company tells its employees that it will pay up to $5,000 in benefits per year and values its benefit offerings this way:

|

Health insurance |

$4,600 |

|

Retirement |

$1,200 |

|

Child care |

$1,200 |

|

Life insurance |

$800 |

Joe, an employee, then picks from the list of benefits until he reaches $5,000. If Joe wants more than $5,000 in benefits, he pays for the additional benefits with a reduction in his paycheck.

The list of possible benefits may be considerably longer, but in this case, if Joe chooses health insurance, retirement, and life insurance, the total cost is $6,600. Because the company pays up to $5,000, Joe needs to co-pay $1,600, a portion of which is taken out of each paycheck. If Joe gets paid every two weeks for a total of 26 paychecks per year, the deduction for benefits from his gross pay is $61.54 ($1,600 ÷ 26).

Cafeteria plans are becoming more popular among larger businesses, but some employers decide not to offer their benefits this way. Primarily, this decision comes because managing a cafeteria plan can be much more time-consuming for the bookkeeping and human resources staff. Many small business employers that do choose to offer a cafeteria plan for benefits do so by outsourcing benefit management services to an outside company that specializes in managing cafeteria plans.

Preparing Payroll and Posting It in the Books

After you know the details about your employees’ withholding allowances and their benefit costs (both of which I cover earlier in the chapter), you can calculate the final payroll and post it to the books.

Calculating payroll for hourly employees

When you’re ready to prepare payroll for nonexempt employees, the first thing you need to do is collect time records from each person being paid hourly. Regardless of whether your company uses time clocks, time sheets, or some other method to produce the required time records, the manager of each department usually reviews the time records for each employee he supervises and then sends those time records to you, the bookkeeper.

With time records in hand, you have to calculate gross pay for each employee. For example, if a nonexempt employee worked 45 hours and is paid $12 an hour, you calculate gross pay like so:

40 regular hours × $12 per hour = $480

5 overtime hours × $12 per hour × 1.5 overtime rate = $90

$480 + $90 = $570

In this case, because the employee isn’t exempt from the FLSA (see “Determining wage and salary types” earlier in this chapter), overtime must be paid for any hours worked over 40 in a seven-day workweek. This employee worked five hours more than the 40 hours allowed, so he needs to be paid at time plus one-half for those extra hours.

Doling out funds to salaried employees

In addition to employees paid based on hourly wages, you also must prepare payroll for salaried employees. Paychecks for salaried employees are relatively easy to calculate — all you need to know are their base salaries and their pay period calculations. For example, if a salaried employee makes $30,000 per year and is paid twice a month (totaling 24 pay periods), that employee’s gross pay is $1,250 for each pay period.

Totaling up for commission checks

Running payroll for employees paid based on commission can involve the most-complex calculations because of the variety of commission scenarios available. To show you a number of variables, in this section I calculate various commission checks based on a salesperson who sells $60,000 worth of products during one month.

Straight commission: For a salesperson on a straight commission of 10 percent, you calculate pay by using this formula:

Straight commission: For a salesperson on a straight commission of 10 percent, you calculate pay by using this formula:

Total amount sold × Commission percentage = Gross pay

$60,000 × 0.10 = $6,000

Base salary plus commission: For a salesperson with a guaranteed base salary of $2,000 plus an additional 5 percent commission on all products sold, you calculate pay by using this formula:

Base salary plus commission: For a salesperson with a guaranteed base salary of $2,000 plus an additional 5 percent commission on all products sold, you calculate pay by using this formula:

Base salary + (Total amount sold × Commission percentage) = Gross pay

$2,000 + ($60,000 × 0.05) = $5,000

Although this employee may be happier having a base salary he can count on each month, he actually makes less with a base salary because the commission rate is so much lower. By selling $60,000 worth of products, he made only $3,000 in commission at 5 percent. Without the base pay, he would’ve made 10 percent on the $60,000 or $6,000, so he actually got paid $1,000 less with a base pay structure that includes a lower commission pay rate.

But the base-salary setup isn’t always less lucrative. If the same salesperson has a slow sales month of just $30,000 worth of products sold, his pay is

$30,000 × 0.10 = $3,000 on straight commission of 10 percent

$30,000 × 0.05 = $1,500 plus $2,000 base salary, or $3,500

For a slow month, the salesperson makes more money with the base salary than with the higher straight commission rate.

Higher commissions on higher levels of sales: This type of pay system encourages salespeople to keep their sales levels over a certain level — in this example, $30,000 — to get the best commission rate.

Higher commissions on higher levels of sales: This type of pay system encourages salespeople to keep their sales levels over a certain level — in this example, $30,000 — to get the best commission rate.

Graduated commission scale: With a graduated commission scale, a salesperson can make a straight commission of 5 percent on his first $10,000 in sales, 7 percent on his next $20,000, and finally 10 percent on anything over $30,000. Here’s what his gross pay calculation looks like using this commission pay scale:

Graduated commission scale: With a graduated commission scale, a salesperson can make a straight commission of 5 percent on his first $10,000 in sales, 7 percent on his next $20,000, and finally 10 percent on anything over $30,000. Here’s what his gross pay calculation looks like using this commission pay scale:

($10,000 × 0.05) + ($20,000 × 0.07) + ($30,000 × 0.10) = $4,900 Gross pay

Determining base salary plus tips

One other type of commission pay system involves a base salary plus tips. (See the preceding section for more on figuring commission pay.) This method is common in restaurant settings in which servers receive between $2.50 and $5 per hour plus tips.

Employees must report tips to their employers on an IRS Form 4070, Employee’s Report of Tips to Employer, which is part of IRS Publication 1244, Employees Daily Record of Tips and Report to Employer. The publication provides details about what the IRS expects you and your employees to do if they work in an environment where tipping is common.

As an employer, you must report an employee’s gross taxable wages based on salary plus tips. Here’s how you calculate gross taxable wages for an employee whose earnings are based on tips and wages:

Base wage + Tips = Gross taxable wages

($3 × 40 hours per week) + $300 = $420

If your employees are paid using a combination of base wage plus tips, you must be sure that your employees are earning at least the minimum wage rate of $7.25 per hour. Checking this employee’s gross wages, the hourly rate earned is $10.50 per hour:

Hourly wage = $10.50 ($420 ÷ 40)

Practice: Payroll Preparation

Q. Suppose Jack, who is paid weekly, earns $12 per hour and worked 48 hours last week. How do you calculate his gross paycheck before deductions?

A. You separate the amount of timed work at regular pay, 40 hours, from the time worked at overtime pay, 8 hours. Then you calculate the gross paycheck this way:

40 hours regular pay × $12 per hour = $480

8 hours overtime pay × $12 per hour × 1.5 overtime rate = $144

$480 + $144 = $624

Q. If Ann earns $3.00 per hour plus $5 per hour in tips, what is her gross paycheck, and what is the total pay you use to calculate her taxes?

A. You calculate her paycheck based on her hourly pay.

$3 × 40 hours work = $120

You figure up her taxes based on her pay plus tips, or $8 per hour.

$8 × 40 hours = $320

4. Suppose John, who gets paid biweekly, earns $15 per hour. He worked 40 hours in the first week of the pay period and 45 hours in the second week of the pay period. How much was his gross pay before deductions?

Solve It

5. Suppose Mary Ann, who gets paid biweekly, earns $13 per hour. She worked 42 hours in the first week and 46 hours in the second week of the pay period. How much is her gross pay before deductions?

Solve It

6. Suppose Bob makes $30,000 per year and is paid semimonthly. He is an exempt employee. How much is his gross pay each pay period?

Solve It

7. Suppose Ginger makes $42,000 per year and is paid monthly. She is an exempt employee. How much is her gross pay each pay period?

Solve It

8. Jim earns a base salary of $1,500 plus 3 percent commission. He is paid monthly. What is his gross paycheck if he has $75,000 in sales?

Solve It

9. Sally earns $4.00 per hour plus $7 per hour in tips. If she works 40 hours, what is her gross paycheck, and what is the total pay you use to calculate her taxes?

Solve It

10. Betty earns $2.50 per hour plus $8 per hour in tips. If she works 40 hours, what is her weekly gross paycheck, and what is the total pay you use to calculate her taxes?

Solve It

Finishing the Job

After calculating paychecks for all your employees, you prepare the payroll, make up the checks, and post the payroll to the books. In addition to Cash, many accounts are impacted by payroll, including the following:

Accrued Federal Withholding Payable, which is where you record the liability for future federal tax payments

Accrued Federal Withholding Payable, which is where you record the liability for future federal tax payments

Accrued State Withholding Payable, which is where you record the liability for future state tax payments

Accrued State Withholding Payable, which is where you record the liability for future state tax payments

Accrued Employee Medical Insurance Payable, which is where you record the liability for future medical insurance premiums

Accrued Employee Medical Insurance Payable, which is where you record the liability for future medical insurance premiums

Accrued Employee Elective Insurance Payable, which is where you record the liability for miscellaneous insurance premiums, such as life or accident insurance

Accrued Employee Elective Insurance Payable, which is where you record the liability for miscellaneous insurance premiums, such as life or accident insurance

When you post the payroll entry, you indicate the withdrawal of money from the Cash account as well as record liabilities for future cash payments that will be due for taxes and insurance payments. Just for the purposes of giving you an example of the proper setup for a payroll journal entry, I assume the total payroll is $10,000 with $1,000 set aside for each type of withholding payable. In reality, your numbers will be much different, and I doubt your payables will ever all be the same. Here’s what your journal entry for posting payroll should look like:

Payroll Posting Journal Entry

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Salaries and Wages Expense |

$10,000 |

|

|

Accrued Federal Withholding Payable |

$1,000 |

|

|

Accrued State Withholding Payable |

$1,000 |

|

|

Accrued Medical Insurance Payable |

$1,000 |

|

|

Accrued Elective Insurance Payable |

$1,000 |

|

|

Cash |

$6,000 |

To record payroll for May 27, 2011.

In this entry, you increase the expense account for salaries and wages as well as all the accounts in which you accrue future obligations for taxes and employee insurance payments. You decrease the amount of the Cash account; when cash payments are made for the taxes and insurance payments in the future, you post those payments in the books. Here’s an example of the entry you would post to the books after making the federal withholding tax payment:

Federal Witholding Tax Posting

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Accrued Federal Withholding Payable |

$ |

|

|

Cash in Checking |

$ |

To record the payment of May 2011 federal taxes for employees.

Depositing Employee Taxes

Any taxes collected on behalf of employees must be deposited in a financial institution authorized to collect those payments for the government or in the Federal Reserve Bank in your area. Most major banks are authorized to collect these deposits; check with your bank to see whether it is or to get a recommendation of a bank you can use. IRS Form 8109, Federal Tax Deposit (FTD) Coupon, is what businesses use to deposit taxes. You can’t get a copy of this form online; it’s only available from the IRS or from a bank that handles your deposits. You can call 800-829-4933 to get a preprinted copy with your business name, address, and Employer Identification Number.

For the purposes of tax payments collected from employees for the federal government, you must complete Form 941. This form summarizes the tax payments made on behalf of employees. You can get instructions and a copy of Form 941 online at www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/f941.pdf (for the form) and www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/i941.pdf (for the instructions). I talk more about the various forms employers must file in Chapter 11.

During the first year as an employer, your company will have to make monthly deposits of employee taxes. Monthly payments must be made by the 15th day of the month following when the taxes were taken. For example, taxes collected from employees in April must be paid by May 15. If the date the deposit is due falls on a weekend or bank holiday, the payment is due on the next day the banks are open.

As your business gets larger, you’ll need to make more frequent deposits. Large employers that accumulate taxes of $100,000 or more in a day must deposit the funds on the next banking day.

You can also make employee tax payments electronically by using the Electronic Federal Tax Payment System (EFTPS). Employers who make payments of more than $200,000 in any tax year must deposit funds by using the EFTPS system. Otherwise, use of the electronic system is voluntary.

Outsourcing Payroll and Benefits Work

Given all that’s required of you to prepare payroll, you may think that your small company would be better off to outsource the work of payroll and benefits. I don’t disagree. Many companies outsource the work (contract with an outside company to handle those functions) because it’s such a specialized area and requires extensive software to manage both payroll and benefits.

If you don’t want to take on payroll and benefits alone but don’t want to send them to an outside company, you can also pay for a monthly payroll service from the software company that provides your accounting software. For example, QuickBooks provides various levels of payroll services for as low as $16 a month depending on the services you require. The QuickBooks payroll features include calculating earnings and deductions, printing checks or making direct deposits, providing updates to the tax tables, and supplying data necessary to complete all government forms related to payroll. The advantage of doing payroll in-house in this manner is that the payroll can then be more easily integrated into the company’s books.

Answers to Problems on Employee Payroll and Benefits

1 Here’s how Carl’s calculations work out:

2 Here’s how Karen’s calculations work out:

3 Here’s how Tom’s calculations work out:

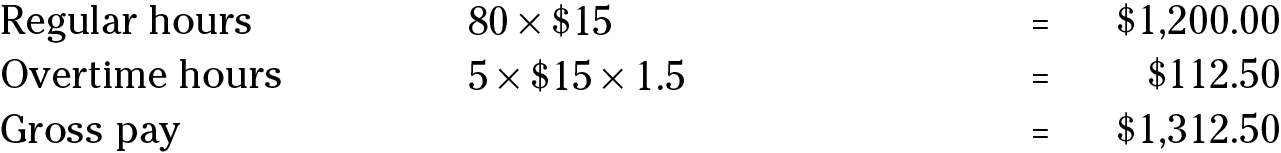

4 Here’s how you calculate John’s paycheck:

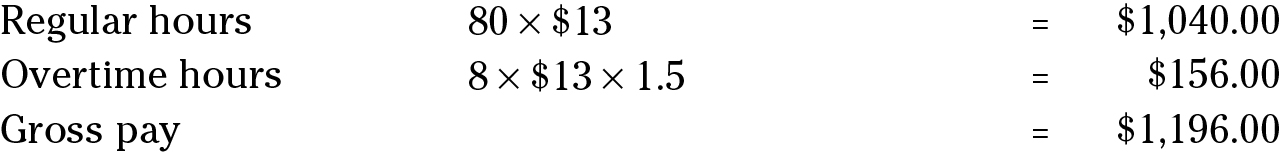

5 Here’s how you calculate Mary Ann’s paycheck:

6 Bob’s gross semimonthly pay is $1,250 (or $30,000/24).

7 Ginger’s gross monthly pay is $3,500 (or $42,000/12).

8 Jim’s gross paycheck is $3,750: $1,500 + $2,250 ($75,000 × .03) = $3,750.

9 Sally’s gross paycheck: $4 × 40 = $160

Pay for tax calculation: $11 × 40 = $440

10 Betty’s gross paycheck: $2.50 × 40 = $100

Pay for tax calculation: $10.50 × 40 = $420

Luckily, the government offers four ways to submit the necessary information and obtain an EIN. The fastest way is to call the IRS’s Business & Specialty Tax Line at 800-829-4933 and complete the form by telephone. IRS officials assign your EIN over the phone. You can also apply online at

Luckily, the government offers four ways to submit the necessary information and obtain an EIN. The fastest way is to call the IRS’s Business & Specialty Tax Line at 800-829-4933 and complete the form by telephone. IRS officials assign your EIN over the phone. You can also apply online at  It’s a good idea to ask an employee to fill out a W-4 immediately, but you can allow him to take the form home if he wants to discuss allowances with his spouse or accountant. If an employee doesn’t complete a W-4, you must take income taxes out of his check based on the highest possible amount for that person. I talk more about taking out taxes in the section “Collecting Employee Taxes” later in this chapter.

It’s a good idea to ask an employee to fill out a W-4 immediately, but you can allow him to take the form home if he wants to discuss allowances with his spouse or accountant. If an employee doesn’t complete a W-4, you must take income taxes out of his check based on the highest possible amount for that person. I talk more about taking out taxes in the section “Collecting Employee Taxes” later in this chapter. If you plan to hire employees who are under the age of 18, you must pay attention to child labor laws. Federal and state laws restrict what kind of work children can do, when they can do it, and how old they have to be to do it, so be sure you become familiar with the laws before hiring employees who are younger than 18. For minors below the age of 16, work restrictions are even tighter than for teens aged 16 and 17. (You can hire your own child without worrying about these restrictions.)

If you plan to hire employees who are under the age of 18, you must pay attention to child labor laws. Federal and state laws restrict what kind of work children can do, when they can do it, and how old they have to be to do it, so be sure you become familiar with the laws before hiring employees who are younger than 18. For minors below the age of 16, work restrictions are even tighter than for teens aged 16 and 17. (You can hire your own child without worrying about these restrictions.) Businesses that pay less than minimum wage must prove that their employees make at least minimum wage when tips are accounted for. Today, that’s relatively easy to prove because most people pay their bills with credit cards and include tips on their bills. Businesses can then come up with an average tip rate by using that credit card data.

Businesses that pay less than minimum wage must prove that their employees make at least minimum wage when tips are accounted for. Today, that’s relatively easy to prove because most people pay their bills with credit cards and include tips on their bills. Businesses can then come up with an average tip rate by using that credit card data.