Solve It

Chapter 11

Employer-Paid Taxes and Government Payroll Reporting

In This Chapter

Tallying up the employer’s share of Social Security and Medicare

Tallying up the employer’s share of Social Security and Medicare

Filing and paying unemployment taxes

Filing and paying unemployment taxes

Figuring out workers’ compensation

Figuring out workers’ compensation

Keeping accurate employee records

Keeping accurate employee records

You may think that employees will make your job as a business owner easier, but I’m afraid you’re wrong on that one. It’s really a mixed bag. Although employees help you keep your business operating and enable you to grow, they also add a lot of government paperwork.

After your company hires employees, you need to complete regular reports for the government regarding the taxes you must pay toward the employees’ Social Security and Medicare, as well as unemployment taxes. In every state except Texas, employers also are required to buy workers’ compensation insurance based on employees’ salaries and wages.

This chapter reviews the federal, state, and local government reporting requirements for employers as well as the records you, the bookkeeper, must keep in order to complete these reports. You also find out how to calculate the various employee taxes and how to buy workers’ compensation insurance.

Note: In Chapter 10, I show you how to calculate the employee side of Social Security and Medicare taxes. This chapter looks at the employer side of these taxes, as well as other employer-paid government taxes.

Paying Employer Taxes on Social Security and Medicare

In the United States, both employers and employees must contribute to the Social Security and Medicare systems. In fact, employers share equally with employees the tax obligation for both Social Security and Medicare.

As I discuss in greater detail in Chapter 10, the employer and the employee each must pay 6.2 percent of an employee’s compensation for Social Security up to a salary of $106,800 in 2011. In 2011 a one-year tax cut of 2 percent lowered that rate to 4.2 percent for employees. As of this writing, whether that tax cut will be extended is unknown.

The percentage both the employer and employee pay toward Medicare is 1.45 percent. There is no salary cap related to the amount that must be paid toward Medicare, so even if your employee makes $1 million (don’t you wish your business was that successful?), you still must pay Medicare taxes on that amount.

When you finish calculating payroll checks, you calculate the employer’s portion of Social Security and Medicare. When you post the payroll to the books, the employer’s portion of Social Security and Medicare are set aside in an accrual account.

Filing Form 941

Each quarter you must file federal Form 941, Employer’s Federal Tax Return, which details the number of employees that received wages, tips, or other compensation for the quarter.

Table 11-1 tells what months are reported during each quarter and when the report is due:

Table 11-1 Filing Requirements for Form 941

|

Months in Quarter |

Report Due Date |

|

January, February, March |

On or before April 30 |

|

April, May, June |

On or before July 31 |

|

July, August, September |

On or before October 31 |

|

October, November, December |

On or before January 31 |

The following key information must be included on Form 941:

Number of employees who received wages, tips, or other compensation in the pay period

Number of employees who received wages, tips, or other compensation in the pay period

Total of wages, tips, and other compensation paid to employees

Total of wages, tips, and other compensation paid to employees

Total tax withheld from wages, tips, and other compensation

Total tax withheld from wages, tips, and other compensation

Taxable Social Security and Medicare wages

Taxable Social Security and Medicare wages

Total paid out to employees in sick pay

Total paid out to employees in sick pay

Adjustments for tips and group-term life insurance

Adjustments for tips and group-term life insurance

Amount of income tax withholding

Amount of income tax withholding

Advance Earned Income Credit payments made to employees (see Chapter 10 for an explanation)

Advance Earned Income Credit payments made to employees (see Chapter 10 for an explanation)

Amount of tax liability per month

Amount of tax liability per month

Knowing how often to file

As an employer, you file Form 941 on a quarterly basis, but you probably have to pay taxes more frequently. Most new employers start out making monthly deposits for taxes due by using Form 8109, which is a payment coupon that your company can get from a bank approved to collect that money or from the Federal Reserve branch near you. Others make deposits online using the IRS’s Electronic Federal Tax Payment System (EFTPS). For more information on EFTPS, go to www.eftps.gov.

Employers on a monthly payment schedule (usually small companies) must deposit all employment taxes due by the 15th day of the following month. For example, the taxes for the payroll in April must be paid by May 15th. Larger employers must pay taxes more frequently. For example, employers whose businesses accumulate $100,000 or more in taxes due on any day during a deposit period must deposit those taxes on the next banking day. If you hit $100,000 due when you’re a monthly depositor, you must start paying taxes semiweekly for at least the remainder of the current tax year.

After you become a semiweekly payer, you must deposit your taxes on Wednesday or Friday, depending on your payday:

If you pay employees on Wednesday, Thursday, or Friday, you must deposit the taxes due by the next Wednesday.

If you pay employees on Wednesday, Thursday, or Friday, you must deposit the taxes due by the next Wednesday.

If you pay employees on Saturday, Sunday, Monday, or Tuesday, you must deposit the taxes due by the next Friday.

If you pay employees on Saturday, Sunday, Monday, or Tuesday, you must deposit the taxes due by the next Friday.

Still-larger employers — that is, those with tax payments due of $200,000 or more — must deposit these taxes electronically by using EFTPS according to the semiweekly payment schedule. Electronic tax payments for employers with tax payments under $200,000 are voluntary.

Completing Unemployment Reports and Paying Unemployment Taxes

If you ever faced unemployment, I’m sure you were relieved to get a weekly check — meager as it may have been — while you looked for a job. Did you realize that unemployment compensation was partially paid by your employer? In fact, an employer pays his share of unemployment compensation based on his record of firing or laying off employees. So think for a moment of your dear employees and your own past experiences, and you’ll see the value of paying toward unemployment compensation.

The fund that used to be known simply as Unemployment is now known as the Federal Unemployment Tax (FUTA) fund. Employers contribute to the fund, but states also collect taxes to fill their unemployment fund coffers.

For FUTA, employers pay a federal rate of 6.2 percent on the first $7,000 that each employee earns. Luckily, you don’t have to just add the state rate on top of that; the federal government allows you to subtract up to 5.4 percent of the first $7,000 per employee, if that amount is paid to the state. Essentially, the amount you pay to the state can serve as a credit toward the amount you must pay to the federal government.

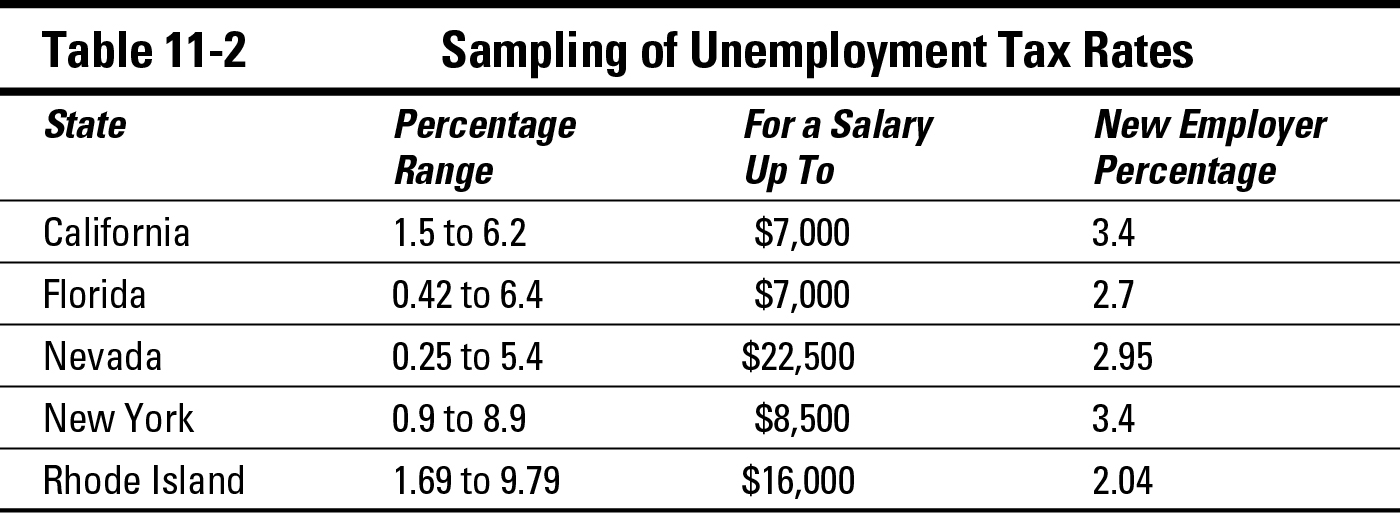

Each state sets its own unemployment tax rate. Many states also charge additional fees for administrative costs and job-training programs. You can check out the full charges for your state at payroll-taxes.com, but to give you an idea of how taxes vary state to state, check out the sampling shown in Table 11-2.

The percentage an employer must pay isn’t a set amount but instead is a percentage range. The employee income amount on which this percentage is charged also varies from state to state. The percentage range is based on the company’s employment history and how frequently its employees collect unemployment.

Examining how states calculate the FUTA tax rate

States use four different methods to calculate how much you may need to pay in FUTA taxes:

Benefit ratio formula: The state looks at the ratio of benefits collected by former employees to your company’s total payroll over the past three years. States also adjust your rate depending on the overall balance in the state unemployment insurance fund.

Benefit ratio formula: The state looks at the ratio of benefits collected by former employees to your company’s total payroll over the past three years. States also adjust your rate depending on the overall balance in the state unemployment insurance fund.

Benefit wage formula: The state looks at the proportion of your company’s payroll that’s paid to workers who become unemployed and receive benefits, and then divides that number by your company’s total taxable wages.

Benefit wage formula: The state looks at the proportion of your company’s payroll that’s paid to workers who become unemployed and receive benefits, and then divides that number by your company’s total taxable wages.

Payroll decline ratio formula: The state looks at the decline in your company’s payrolls from year to year or from quarter to quarter.

Payroll decline ratio formula: The state looks at the decline in your company’s payrolls from year to year or from quarter to quarter.

Reserve ratio formula: The state keeps track of your company’s balance in the unemployment reserve account, which gives a cumulative representation of its use by your former employees that were laid off and paid unemployment. This record keeping dates back from the date you were first subject to the state unemployment rate. The reserve account is calculated by adding up all your contributions to the account and then subtracting total benefits paid. This amount is then divided by your company’s total payroll. The higher the reserve ratio, the lower the required contribution rate.

Reserve ratio formula: The state keeps track of your company’s balance in the unemployment reserve account, which gives a cumulative representation of its use by your former employees that were laid off and paid unemployment. This record keeping dates back from the date you were first subject to the state unemployment rate. The reserve account is calculated by adding up all your contributions to the account and then subtracting total benefits paid. This amount is then divided by your company’s total payroll. The higher the reserve ratio, the lower the required contribution rate.

Calculating FUTA tax

After you know what your rate is, calculating the actual FUTA tax you owe isn’t difficult.

Consider a new company that’s just getting started in the state of Florida; it has ten employees, and each employee makes more than $7,000 per year. For state unemployment taxes, I use the new employer rate of 2.7 percent on the first $7,000 of income. The federal FUTA is the same for all employers — 6.2 percent. Here’s how you calculate the FUTA tax for this company:

State unemployment taxes:

$7,000 × 0.027 = $189 per employee

$189 × 10 employees = $1,890

Federal unemployment taxes:

$7,000 × 0.062 = $434

$434 × 10 employees = $4,340

The company doesn’t have to pay the full federal amount because it can take up to a 5.4-percent credit for state taxes paid ($7,000 × 0.054 = $378). Because in this example state taxes in Florida are only 2.7 percent of $7,000, this employer can subtract the full amount of Florida FUTA taxes from the federal FUTA tax:

$4,340 – $1,890 = $2,450

So this company only needs to pay $2,450 to the federal government in FUTA taxes. Any company paying more than $378 per employee to the state is only able to reduce its federal bill by the maximum of $378 per employee. So, every employer pays at least $56 per employee into the federal FUTA pool.

Each year, you must file IRS Form 940, Employer’s Annual Federal Unemployment (FUTA) Tax Return. You can find Form 940 with its instructions online at www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/f940.pdf.

Filing and paying unemployment taxes to state governments

States collect their unemployment taxes on a quarterly basis, and many states allow you to pay your unemployment taxes online. Check with your state to find out how to file and make unemployment tax payments.

Unfortunately, the filing requirements for state unemployment taxes are much more difficult to complete than those for federal taxes (see the discussion of Federal Form 940 in the preceding section). States require you to detail each employee by name and Social Security number because that’s how unemployment records are managed at the state level. The state must know how much an employee was paid each quarter in order to determine his or her unemployment benefit, if the need arises. Some states also require you to report the number of weeks an employee worked in each quarter because the employee’s unemployment benefits are calculated based on the number of weeks worked.

Each state has its own form and filing requirements. Some states require a detailed report as part of your quarterly wage and tax reports. Other states allow a simple form for state income tax and a more detailed report with your unemployment tax payment.

Practice: Calculating FUTA Tax

1. Using Table 11-2 earlier in the chapter, calculate the FUTA taxes for a new employer in the state of California. He has ten employees who earn more than $20,000 each.

2. Using Table 11-2, calculate the FUTA taxes for a new employer in the state of Nevada. He has ten employees. Eight earn $20,000 each, one earns $24,000, and one earns $30,000.

Solve It

3. Using Table 11-2, calculate the FUTA taxes for a new employer in the state of New York. He has ten employees who earn more than $30,000 each.

Solve It

4. Using Table 11-2, calculate the FUTA taxes for a new employer in the state of Rhode Island. He has ten employees. Eight workers earn $14,000. One earns $24,000, and one earns $30,000.

Solve It

Carrying Workers’ Compensation Insurance

Taxes aren’t the only thing you need to worry about when figuring out your state obligations after hiring employees. Every state (except Texas) requires employers to carry workers’ compensation insurance, which covers costs of lost income, medical expenses, vocational rehabilitation, and, if applicable, death benefits for your employees in case they’re injured on the job. Texas doesn’t require this insurance but permits employees injured on the job to sue their employers in civil court to recoup the costs of injuries.

Each other state sets its own rules regarding how much medical coverage you must provide. If the injury also causes the employee to miss work, the state determines what percentage of the employee’s salary you must pay and how long you pay that amount. If the injury results in the employee’s death, the state also sets the amount you must pay toward funeral expenses and the amount of financial support you must provide the employee’s family.

The state also decides who gets to pick the physician that will care for the injured employee; options are the employer, the employee, the state agency, or a combination of these folks. Most states allow either the employer or the injured employee to choose the physician.

Additionally, each state makes up its own rules about how a company must insure itself against employee injuries on the job. Some states create state-based workers’ compensation funds to which all employers must contribute. Other states allow you the option of participating in a state-run insurance program or buying insurance from a private company. A number of states permit employers to use HMOs, PPOs, or other managed-care providers to handle workers’ claims. If your state doesn’t have a mandatory state pool, you’ll find that shopping around for the best private rates doesn’t help you much. States set the requirements for coverage, and premiums are established by either a national rating bureau called the National Council on Compensation Insurance (NCCI) or a state rating bureau. For the lowdown on NCCI and workers’ compensation insurance, visit www.ncci.com.

You may find lower rates over the long-term if your state allows you to buy private workers’ compensation insurance. Many private insurers give discounts to companies with good safety standards in place and few past claims. So the best way to keep your workers’ compensation rates low is to encourage safety and minimize your company’s claims.

Your company’s rates are calculated based on risks identified in two areas:

Classification of the business: These classifications are based on historic rates of risk in different industries. For example, if you operate a business in an industry that historically has a high rate of employee injury, such as a construction business, your base rate for workers’ compensation insurance is higher than that of a company in an industry without a history of frequent employee injury, such as an office that sells insurance.

Classification of the business: These classifications are based on historic rates of risk in different industries. For example, if you operate a business in an industry that historically has a high rate of employee injury, such as a construction business, your base rate for workers’ compensation insurance is higher than that of a company in an industry without a history of frequent employee injury, such as an office that sells insurance.

Classification of the employees: The NCCI publishes classifications of over 700 jobs in a book called the Scopes Manual. Most states use this manual to develop the basis for their classification schedules. For example, businesses that employ most workers at desk jobs pay less in workers’ compensation than businesses with a majority of employees operating heavy machinery because more workers are hurt operating heavy machinery than working at desks.

Classification of the employees: The NCCI publishes classifications of over 700 jobs in a book called the Scopes Manual. Most states use this manual to develop the basis for their classification schedules. For example, businesses that employ most workers at desk jobs pay less in workers’ compensation than businesses with a majority of employees operating heavy machinery because more workers are hurt operating heavy machinery than working at desks.

Be careful how you classify your employees. Many small businesses pay more than needed for workers’ compensation insurance because they misclassify employees. Be sure you understand the classification system and properly classify your employee positions before applying for workers’ compensation insurance. Be sure to read the information on the NCCI website before classifying your employees.

Be careful how you classify your employees. Many small businesses pay more than needed for workers’ compensation insurance because they misclassify employees. Be sure you understand the classification system and properly classify your employee positions before applying for workers’ compensation insurance. Be sure to read the information on the NCCI website before classifying your employees.

When computing insurance premiums for a company, the insurer (whether the state or a private firm) looks at employee classifications and the rate of pay for each employee. For example, consider the position of a secretary who earns $25,000 per year. If that job classification is rated at 29 cents per $100 of income, the workers’ compensation premium for that secretary is $72.50.

Most states allow you to exclude any overtime paid when calculating workers’ compensation premiums. You may also be able to lower your premiums by paying a deductible on claims. A deductible is the amount you have to pay before the insurance company pays anything. Deductibles can lower your premium by as much as 25 percent, so consider that route as well to keep your upfront costs low.

Maintaining Employee Records

One thing that’s abundantly clear when you consider all the state and federal filing requirements for employee taxes is that you must keep very good employee records. Otherwise, you’ll have a hard time filling out all the necessary forms and providing quarterly detail on your employees and your payroll. The best way to track employee information with a manual bookkeeping system is to set up an employee journal and create a separate journal page for each employee. (I get into how to set up journals in Chapter 5.)

The detailed individual records you keep on each employee should include this basic information, most of which is collected or determined as part of the hiring process:

Name, address, phone number, and Social Security number

Name, address, phone number, and Social Security number

Department or division within the company

Department or division within the company

Start date with the company

Start date with the company

Pay rate

Pay rate

Pay period (weekly, biweekly, semimonthly, or monthly)

Pay period (weekly, biweekly, semimonthly, or monthly)

Whether hourly or salaried

Whether hourly or salaried

Whether exempt or nonexempt

Whether exempt or nonexempt

W-4 withholding allowances

W-4 withholding allowances

Benefits information

Benefits information

Payroll deductions

Payroll deductions

All payroll activity

All payroll activity

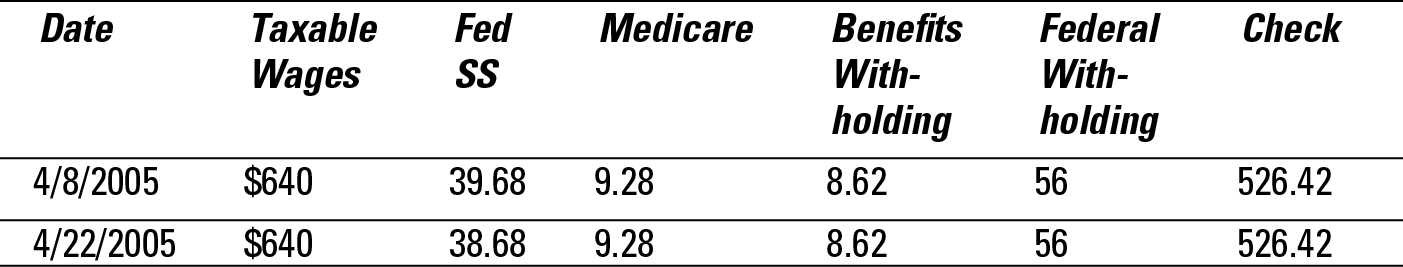

The personal detail that doesn’t change each pay period should appear at the top of the journal page. Then, you divide the remaining information into at least seven columns. Here’s a sample of what an employee’s journal page may look like:

The following sample journal page contains only seven columns: date of check, taxable wages, Social Security tax, Medicare tax, benefits withholding, federal withholding, and net check amount. (In many states, you’d include an eighth column for state withholding, but the state tax in the sample is zero because this particular employee works in a nonincome tax state.)

You may want to add other columns to your employee journal to keep track of things such as

Non-taxable wages: This designation can include items such as health or retirement benefits that are paid before taxes are taken out.

Non-taxable wages: This designation can include items such as health or retirement benefits that are paid before taxes are taken out.

Benefits: If the employee receives benefits, you need at least one column to track any money taken out of the employee’s check to pay for those benefits. In fact, you may want to consider tracking each benefit in a separate column.

Benefits: If the employee receives benefits, you need at least one column to track any money taken out of the employee’s check to pay for those benefits. In fact, you may want to consider tracking each benefit in a separate column.

Sick time

Sick time

Vacation time

Vacation time

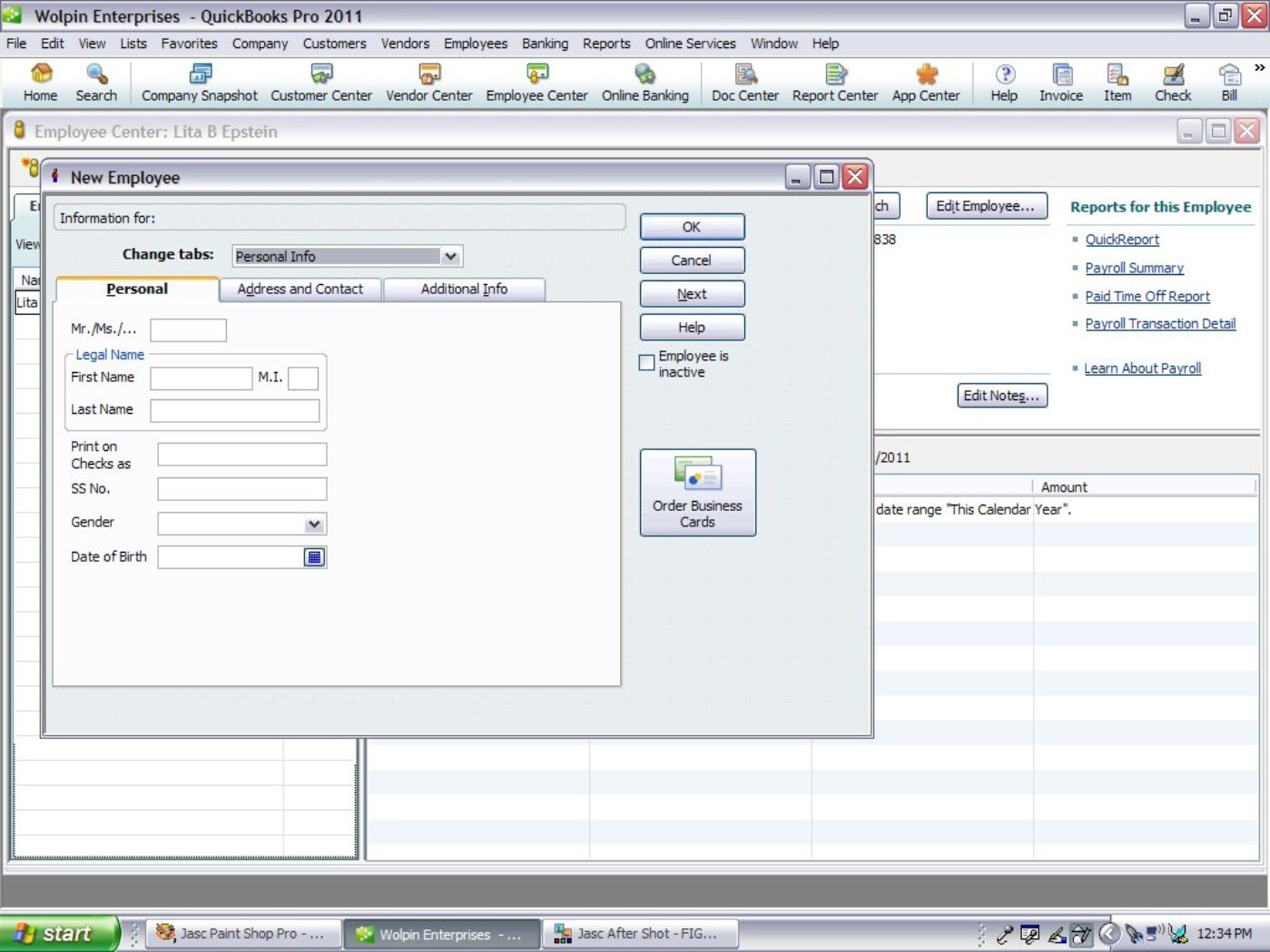

Clearly, these employee journal sheets can get very lengthy very quickly. That’s why many small businesses use computerized accounting systems to monitor both payroll and employee records. Figure 11-1 shows you how a new employee is added to the QuickBooks system.

Figure 11-1: New employee personal and contact information.

Image Credit: Intuit

Answers to Problems on Employer-Paid Taxes and Government Payroll Reporting

1 You first calculate state unemployment taxes by multiplying 3.4 percent by $7,000, which is the maximum amount of salary upon which the employer must pay unemployment taxes. Then multiply that number by 10 (because the employees all earn higher than the maximum): .034 × 7,000 × 10 = $2,380.

FUTA taxes are (.062 × $7,000 × 10) – amount due state ($2,380) = $1,960.

2 You first calculate state unemployment taxes for the eight employees earning $20,000 by multiplying $20,000 × .0295 × 8 = $4,720 (or $590 per employee).

For the two employees earning more than $22,500, the calculation is $22,500 × .0295 × 2 = $1,327.50.

Because the maximum FUTA credit is $378 per employee and the employer pays more than that per employee, you can subtract $378 × 10 employees, or $3,780, from the amount due the federal government on FUTA (.062 × $7,000 × 10) – $3,780 = $560.

Amount due Nevada: $4,720 + 1,327.50 = $6,047.50

3 You first calculate the state unemployment taxes by multiplying $8,500 × .034 × 10 = $2,890 (or $289 per employee).

FUTA taxes are (.062 × $7,000 × 10) – $2,890 = $1,450.

4 You first calculate state unemployment taxes for the eight employees earning $14,000 by multiplying $14,000 × .0204 × 8 = $2,284.80 (or $285.60 per employee).

$16,000 × .0204 × 2 = $652.80 (or $326.40).

Because the maximum FUTA credit is $378 per employee, the FUTA deduction is $2,284.80 + 652.80 = $2,937.60

FUTA tax due is (.062 × 7,000 × 10) – $2,937.60 = $1,402.40.

However you’re required to pay your payroll-based taxes, one thing you definitely don’t want to do is underpay. Interest and penalty charges for late payment can make your tax bite even higher — and I’m sure you’re convinced it’s high enough already. If you find it hard to accurately estimate your quarterly tax payment, your best bet is to pay a slightly higher amount in the first and second month of a quarter. Then, if you’ve paid a bit more than needed, you can cut back the payment for the third month of the quarter. This strategy lets you avoid the possibility of underpaying in the first two months of a quarter and risking interest and penalty charges.

However you’re required to pay your payroll-based taxes, one thing you definitely don’t want to do is underpay. Interest and penalty charges for late payment can make your tax bite even higher — and I’m sure you’re convinced it’s high enough already. If you find it hard to accurately estimate your quarterly tax payment, your best bet is to pay a slightly higher amount in the first and second month of a quarter. Then, if you’ve paid a bit more than needed, you can cut back the payment for the third month of the quarter. This strategy lets you avoid the possibility of underpaying in the first two months of a quarter and risking interest and penalty charges.