Solve It

Chapter 13

Paying and Collecting Interest

In This Chapter

Understanding interest calculations

Understanding interest calculations

Putting interest income into the books

Putting interest income into the books

Calculating loan interest

Calculating loan interest

Few businesses are able to make major purchases without taking out loans. Whether loans are for vehicles, buildings, or other business needs, businesses must pay interest, a percentage of the amount loaned, to whoever loans them the money.

Some businesses loan their own money and receive interest payments as income. In fact, a savings account can be considered a type of loan because by placing your money in the account, you’re giving the bank the opportunity to loan that money to others. So the bank pays you for the use of your money by paying interest, which is a type of income for your company.

This chapter reviews different types of loans and how to calculate and record interest expenses for each type. In addition, I discuss how you calculate and record interest income in your business’s books.

Deciphering Types of Interest

Any time you make use of someone else’s (such as a bank’s) money, you have to pay interest for that use whether you’re buying a house, a car, or some other item you want. The same is true for someone else who’s using your money.

The financial institution that has your money will likely combine it with that of other depositors and loan it out to other people to make more interest than the institution is paying you. That’s why when the interest rates you have to pay on loans are low, the interest rates you can earn on savings are even lower.

Banks actually use two types of interest calculations, which I cover in the following sections:

Simple interest is calculated only on the principal amount of the loan.

Simple interest is calculated only on the principal amount of the loan.

Compound interest is calculated on the principal and on interest earned.

Compound interest is calculated on the principal and on interest earned.

Simple interest

Simple interest is simple to calculate. Here’s the formula for calculating simple interest, where n represents the period of the loan:

Principal × interest rate × n = interest

To show you how interest is calculated, I assume that someone deposited $10,000 in the bank in a money market account earning 3 percent (0.03) interest for 3 years. So the interest earned over 3 years is $10,000 × .03 × 3 = $900.

Compound interest

Compound interest is computed on both the principal and any interest earned. You must calculate the interest each compounding period (often a year) and add it to the balance before you can calculate the next period’s interest payment, which will be based on both the principal and interest earned.

Here’s how you calculate compound interest:

|

Principal × interest rate |

= interest for period one |

|

(Principal + interest earned in period one) × interest rate |

= interest for period two |

|

(Principal + interest earned in periods one and two) × interest rate |

= interest for period three |

You repeat this calculation for all periods of the deposit or loan. However, if you pay the total interest due each period, you don’t have any interest to compound.

To show you how compounding interest impacts earnings, I calculate the three-year deposit of $10,000 at 3 percent (0.03):

|

$10,000 × .03 |

= |

$300 interest for year one |

|

($10,000 + 300) × .03 |

= |

$309 interest for year two |

|

($10,000 + 300 +309) × .03 |

= |

$318.27 interest for year three |

|

Total Interest Earned |

= |

$927.27 |

You can see that you earn an extra $27.27 during the first three years of that deposit if the interest is compounded rather than calculated simply (see the preceding section). When working with much larger sums or higher interest rates for longer periods of time, compound interest can make a big difference in how much you earn or how much you pay on a loan.

Practice: Calculating Simple and Compound Interest

1. What is the simple interest earned over five years for a $20,000 savings account at 1.5 percent?

2. What is the simple interest earned over seven years on a $5,000 savings account at 3 percent?

Solve It

3. What is the compound interest earned over five years for a $20,000 savings account compounded annually at 1.5 percent?

Solve It

4. What is the compound interest earned over six years on a $5,000 certificate of deposit compounded annually at 3 percent?

Solve It

Handling Interest Income

The income that your business earns from its savings accounts, certificates of deposit, or other investment vehicles is called interest income. As the bookkeeper, you’re rarely required to calculate interest income by using the simple interest or compounded interest formulas described in the earlier sections of this chapter. In most cases, the financial institution sends you a monthly, quarterly, or annual statement that has a separate line item reporting interest earned.

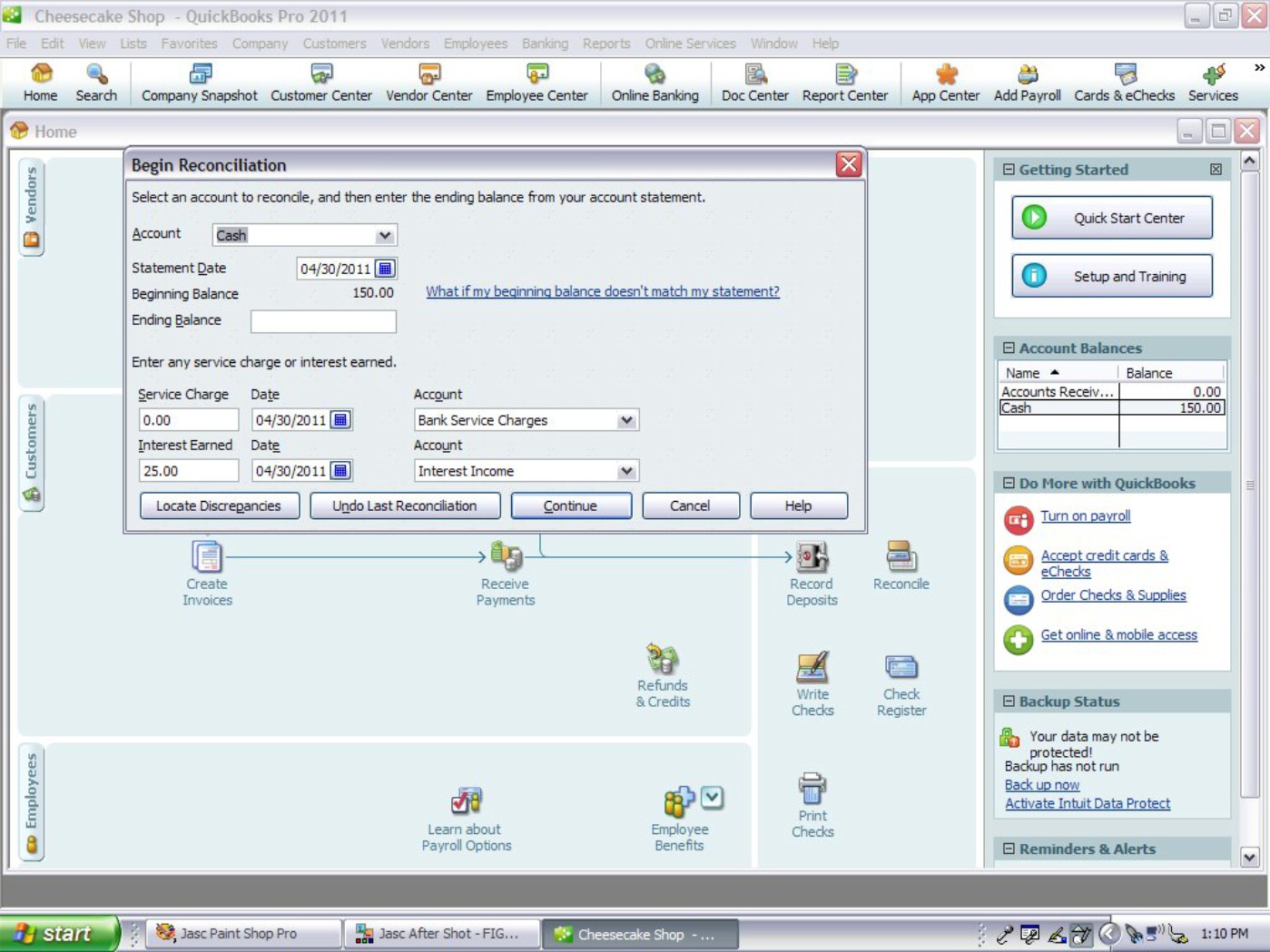

When you get your statement, you then reconcile the books. Reconciliation is a process in which you prove out whether the amount the bank says you have in your account is equal to what you think you have in your account. I talk more about reconciling bank accounts in Chapter 14; the reason I mention it here is that the first step in the reconciliation process involves recording any interest earned or bank fees owed in the books so that your balance matches what the bank shows. Figure 13-1 shows you how to record $25 in interest income.

If you’re keeping the books manually, you create a journal entry similar to this one to record interest:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Cash |

XXX |

|

|

Interest Income |

XXX |

|

|

To record interest income from American Savings Bank. |

||

Figure 13-1: In Quick-Books, you enter interest income at the beginning of the account reconciliation process.

Image Credit: Intuit

When preparing financial statements, you show interest income on the income statement (see Chapter 19 for more information about the income statement) in a section called Other Income. Other Income includes any income your business earned that wasn’t directly related to your primary business activity — selling your goods or services.

Delving Into Loans and Interest Expenses

Businesses borrow money for both short-term periods (periods of 12 months or less) and long-term periods (periods of more than one year). Short-term debt usually involves some form of credit-card debt or line-of-credit debt. Long-term debt can include a 5-year car loan, 20-year mortgage, or any other type of debt that is paid over more than one year. The following sections show you how to deal with these debt types in more detail.

Short-term debt

You show any money due in the next 12-month period as short-term or current debt on the balance sheet. Any interest paid on that money is shown as an Interest Expense on the income statement. The following sections look at a couple of types of short-term debt.

Looking at how credit card interest is calculated

In most cases, you don’t have to calculate your interest due. The financial institution sending you a bill gives you a breakdown of the principal and interest to be paid. For example, when you get a credit-card bill at home, a line always shows you new charges, the amount to pay in full to avoid all interest, and the amount of interest charged during the current period on any money not paid from the previous bill.

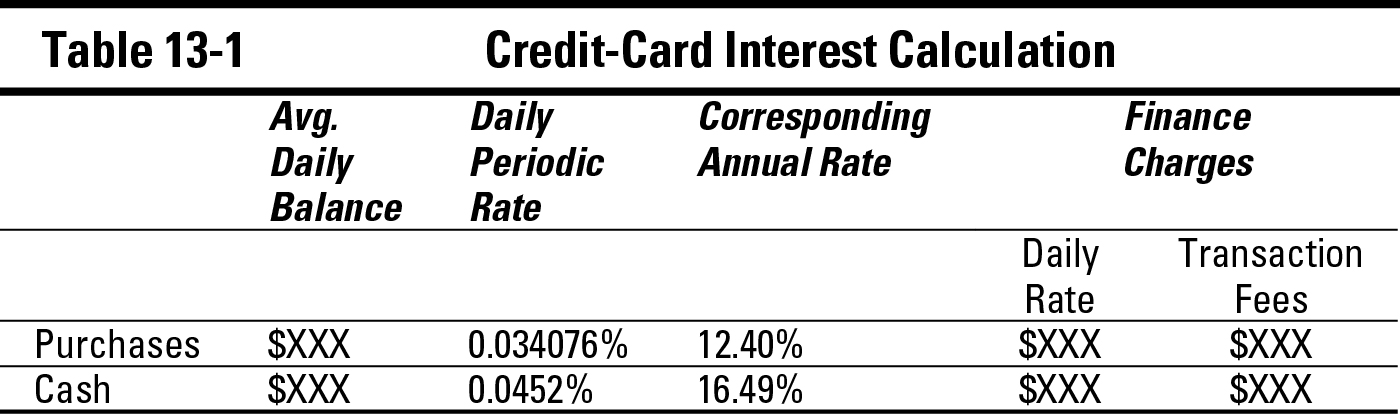

If you don’t pay your credit in full, interest on most cards is calculated by using a daily periodic rate of interest, which is compounded each day based on the unpaid balance. Yes, credit cards are a type of compounded interest. When not paid in full, interest is calculated on the unpaid principal balance plus any unpaid interest. Table 13-1 shows what a typical interest calculation looks like on a credit card.

When opening a credit-card account for your business, be sure you understand how interest is calculated and when the bank starts charging on new purchases. Some issuers give a grace period of 20 to 30 days before charging interest, while others don’t give any type of grace period at all. On many credit cards, you start paying interest on new purchases immediately if you haven’t paid your balance due in full the previous month.

Using credit lines

As a small business owner, you get better interest rates by using a line of credit with a bank rather than a credit card because interest rates are usually lower on lines of credit. Typically, a business owner uses a credit card for purchases, but if he can’t pay the bill in full, he draws money from his line of credit rather than carry over the credit-card balance.

When the money is first received from the credit line, you record the cash receipt and the liability. Just to show you how this transaction works, I record the receipt of a credit line of $1,500. Here is what the journal entry looks like:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Cash |

1,500 |

|

|

Credit Line Payable |

1,500 |

|

|

To record receipt of cash from credit line. |

||

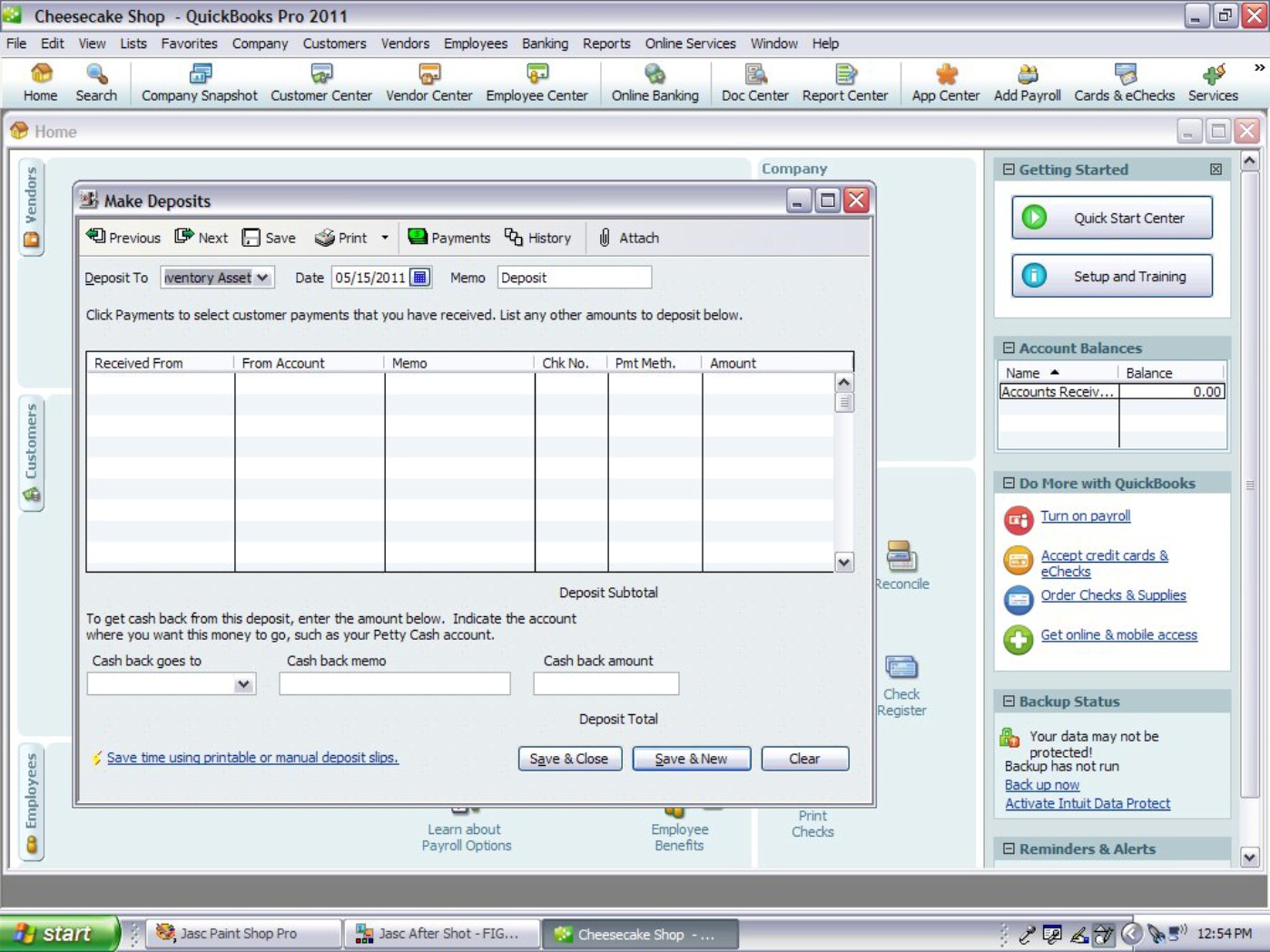

In this entry, you increase the Cash account and the Credit Line Payable account balances. If you’re using a computerized accounting program, you record the transaction by using the deposit form, as shown in Figure 13-2.

Figure 13-2: Recording receipt of cash from credit line.

Image Credit: Intuit

When you make your first payment, you must record the use of cash, the amount paid on the principal of the loan, and the amount paid in interest. Here is what that journal entry looks like:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Credit Line Payable |

150 |

|

|

Interest Expense |

10 |

|

|

Cash |

160 |

|

|

To make monthly payment on credit line. |

||

This journal entry reduces the amount due in the Credit Line Payable account, increases the amount paid in the Interest Expense account, and reduces the amount in the Cash account.

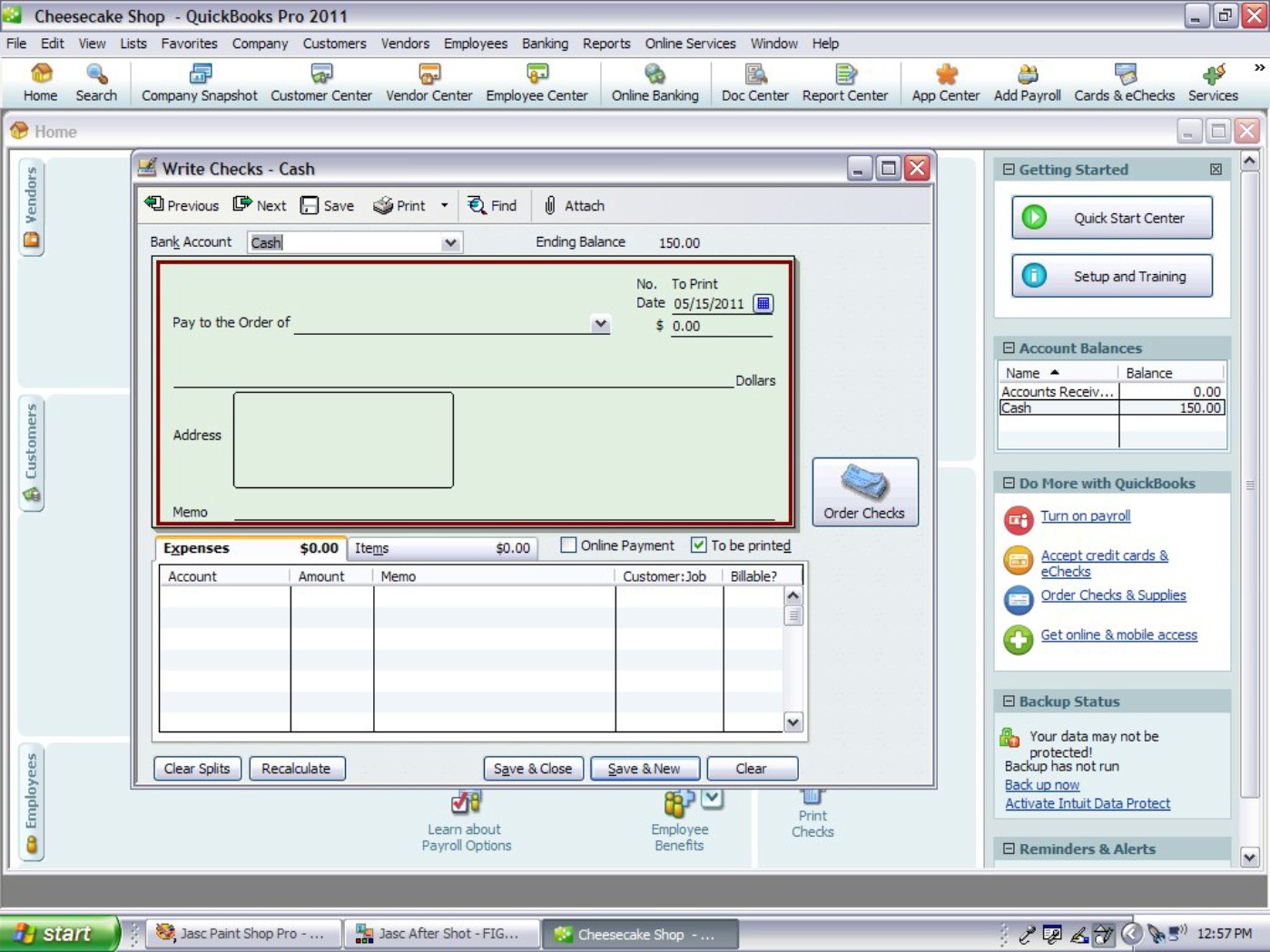

If you’re using a computerized system, you simply complete a check form and indicate which accounts are impacted by the payment, and the system updates the accounts automatically. Figure 13-3 shows you how to record a loan payment in QuickBooks.

Figure 13-3: Recording a loan payment in QuickBooks.

Image Credit: Intuit

As you can see in Figure 13-3, you first write out the check just like you would if you were paying a bill with a paper check. Then, at the bottom of the check, you indicate the portion of the payment that should be recorded toward the principal of the loan and which account is impacted (paid down). You also designate the amount of interest that should be recorded as an Interest Expense. At the top of the check, you specify which account will be used to pay the bill. QuickBooks can then print the check and update all affected accounts. You don’t need to do any additional postings to update your books.

Long-term debt

Most companies take on some form of debt that will be paid over a period of time that is longer than 12 months. This debt may include car loans, mortgages, or promissory notes. A promissory note is a written agreement where you agree to repay someone a set amount of money at some point in the future at a particular interest rate. It can be monthly, yearly, or some other term specified in the note. Most installment loans are types of promissory notes.

Recording a debt

When the company first takes on the debt, it’s recorded in the books in much the same way as a short-term debt (see the earlier section “Using credit lines”):

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Cash |

XXX |

|

|

Notes Payable |

XXX |

|

|

To record receipt of cash from American Bank promissory note. |

||

Payments are also recorded in a manner similar to short-term debt:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Notes Payable |

XXX |

|

|

Interest Expense |

XXX |

|

|

Cash |

XXX |

|

|

To record payment on American Bank promissory note. |

||

You record the initial long-term debt and make payments the same way in QuickBooks as you do for short-term debt.

Unlike short-term debt, long-term debt is split and shown in different line items. The portion of the debt due in the next 12 months is shown in the Current Liabilities section, which is usually a line item named something like Current Portion of Long-Term Debt. The remaining balance of the long-term debt — the portion due beyond the next 12 months — appears in the Long-Term Liability section of the balance sheet as Notes Payable.

Major purchases and long-term debt

Sometimes a long-term liability is set up at the same time as you make a major purchase. You may pay some portion of the amount due in cash as a down payment and the remainder as a note. To show you how to record such a transaction, I assume that a business has purchased a truck for $25,000, made a down payment of $5,000, and taken a note at an interest rate of 6 percent for $20,000. Here’s how you record this purchase in the books:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Vehicles |

25,000 |

|

|

Cash |

5,000 |

|

|

Notes Payable – Vehicles |

20,000 |

|

|

To record payment the purchase of the blue truck. |

||

You then record payments on the note in the same way as any other loan payment:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Notes Payable – Vehicles |

XXX |

|

|

Interest Expense |

XXX |

|

|

Cash |

XXX |

|

|

To record payment the purchase of the blue truck. |

||

When recording the payment on a long-term debt for which you have a set installment payment, you may not get a breakdown of interest and principal with every payment. For example, many times when you take out a car loan, you get a coupon book with just the total payment due each month. Each payment includes both principal and interest, but you don’t get any breakdown detailing how much goes toward interest and how much goes toward principal.

Separating principal and interest

Why is separating principal and interest a problem for recording payments? Each payment includes a different amount for principal and for interest. At the beginning of the loan, the principal is at its highest amount, so the amount of interest due is much higher than later in the loan payoff process when the balance is lower. Many times in the first year of notes payable on high-price items, such as a mortgage on a building, you’re paying more interest than principal.

In order to record long-term debt for which you don’t receive a breakdown each month, you need to ask the bank that gave you the loan for an amortization schedule. An amortization schedule lists the total payment, the amount of each payment that goes toward interest, the amount that goes toward principal, and the remaining balance to be paid on the note.

Some banks provide an amortization schedule automatically when you sign all the paperwork for the note. If your bank can’t give you one, you can easily get one online by using an amortization calculator. BankRate.com has a good one at www.bankrate.com/brm/amortization-calculator.asp.

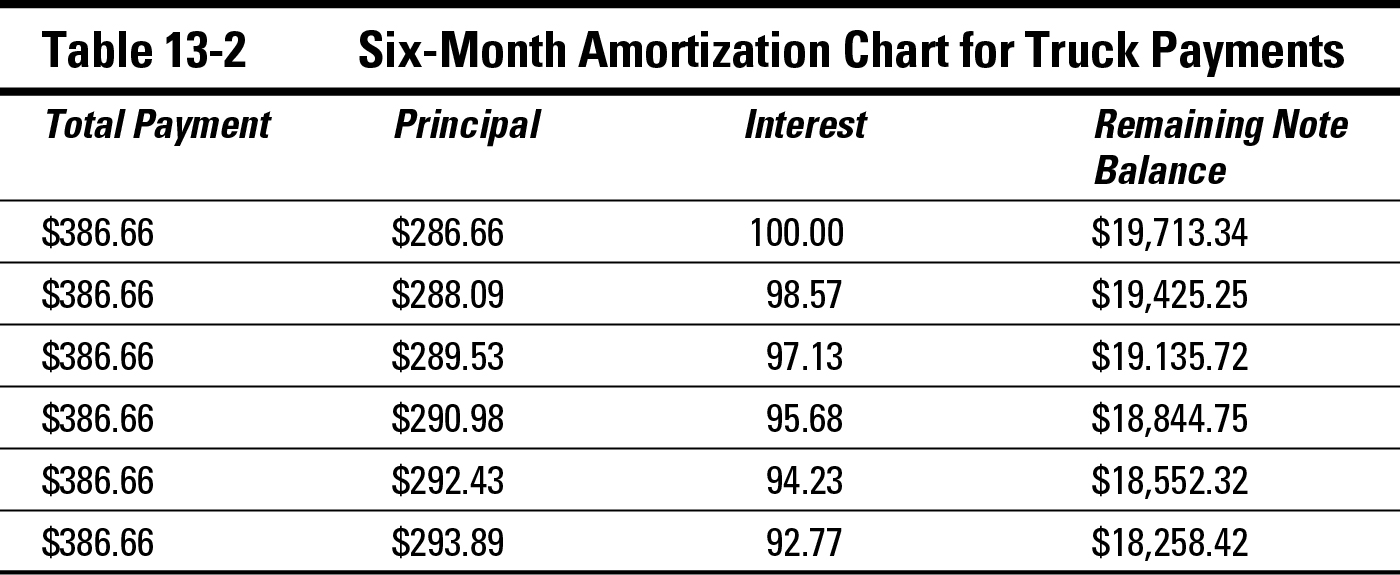

Using that calculator, I list the principal/interest breakdown for the first six months of payment on the truck in a six-month amortization chart. You can see from Table 13-2 that the amount paid to principal on a long-term note gradually increases, while the amount of interest paid gradually decreases as the note balance is paid off. The calculator did calculate payments for all 60 months, but I don’t include them all here.

Looking at the six-month amortization chart, here’s what you need to record in the books for the first payment on the truck:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Notes Payable – Vehicles |

286.66 |

|

|

Interest Expense |

100.00 |

|

|

Cash |

386.66 |

|

|

To record payment on note for blue truck. |

||

In reading the amortization chart in Table 13-2, notice how the amount paid toward interest is slightly less each month as the balance on the note still due is gradually reduced. Also, the amount paid toward the principal of that note gradually increases as less of the payment is used to pay interest.

By the time you start making payments for the final year of the loan, interest costs drop dramatically because the balance is so much lower. For the first payment of year 5, the amount paid in interest is $22.47, and the amount paid on principal is $364.19. The balance remaining after that payment is $4,128.34.

Practice: Calculating and Recording Credit and Long-Term Debt Payments

Q. A businessman draws $1,000 from his line of credit with an 8-percent simple interest rate. How much interest will he pay each month that he has the loan? Assume he pays the total interest due each month, which means that the balance stays constant each month.

A. $1,000 × .08 = $80 – annual interest due

80 ÷ 12 = $6.67 monthly interest due

Q. How do you record a cash payment on a line of credit of $500 plus $35 interest?

A. Here’s how you record the payment:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Credit Line Payable |

$500 |

|

|

Interest Expense |

$35 |

|

|

Cash |

$535 |

5. A businessman draws $5,000 from his line of credit with a 10-percent simple interest rate. How much interest will he pay each month that he has the loan? Assume he pays the total interest due each month plus $500. Calculate six months of payments.

Solve It

6. A businessman draws $10,000 from his line of credit with an 8-percent simple interest rate. How much interest will he pay each month that he has the loan? Assume he pays the total interest due each month plus $1,000. Calculate six months of payments.

Solve It

7. How do you record the cash payment of a credit card if you pay $36 in interest and $200 toward purchases made?

Solve It

8. How do you record the cash payment of a credit card for $47 interest only?

Solve It

9. How do you record the cash payment of $150 of interest only toward a line of credit?

Solve It

10. How do you record the cash payment of $500 plus $85 interest toward a line of credit?

Solve It

11. Using an amortization calculator, calculate the first three months of payments for a $300,000, 30-year mortgage at 6 percent and record the first payment.

Solve It

12. Using an amortization calculator, calculate the first three months of payments for a $25,000, 5-year car loan at 8 percent and record the first payment.

Solve It

Answers to Problems on Paying and Collecting Interest

1 $20,000 × .015 × 5 = $1,500

2 $5,000 × .03 × 7 = $1,050

3 Year 1 = $20,000 × .015 = $300.00

Year 2 = $20,300 × .015 = $304.50

Year 3 = $20,604.50 × .015 = $309.07

Year 4 = $20,913.57 × .015 = $313.70

Year 5 = $21,227.27 × .015 = $318.41

4 Year 1 = $5,000 × .03 = $150.00

Year 2 = $5,150 × .03 = $154.50

Year 3 = $5,304.50 × .03 = $159.14

Year 4 = $5,463.64 × .03 = $163.91

Year 5 = $5,627.55 × .03 = $168.83

Year 6 = $5,796.38 × .03 = $173.89

5 $5,000 × .10 = $500 annual interest

500 ÷ 12 = $41.67 monthly interest

Payment 1: $541.67; Balance $4,500

Payment 2: $4,500 × .10 = $450 annual interest; 450 ÷ 12 = $37.50 monthly interest

Payment $537.50; Balance $4,000

Payment 3: $4,000 × .10 = $400 annual interest; 400 ÷ 12 = $33.33 monthly interest

Payment $533.33; Balance $3,500

Payment 4: $3,500 × .10 = $350 annual interest; 350 ÷ 12 = $29.17 monthly interest

Payment $529.16; Balance $3,000

Payment 5: $3,000 × .10 = $300 annual interest; 300 ÷ 12 = $25 monthly interest

Payment $525; Balance $2,500

Payment 6: $2,500 × .10 = $250 annual interest; 250 ÷ 12 = $20.83

Payment $520.83; Balance $2,000

6 $10,000 × .08 = $800 annual interest

800 ÷ 12 = $66.67 monthly interest

Payment 1: $1,066.67; Balance $9,000

Payment 2: $9,000 × .08 = $720 annual interest; 720 ÷ 12 = $60 monthly interest

Payment $1,060; Balance $8,000

Payment 3: $8,000 × .08 = $640 annual interest; 640 ÷ 12 = $53.33 monthly interest

Payment $1,053.33; Balance $7,000

Payment 4: $7,000 × .08 = $560 annual interest; 560 ÷ 12 = $46.67 monthly interest

Payment $1,046.67; Balance $6,000

Payment 5: $6,000 × .08 = $480 annual interest; 480 ÷ 12 = $40 monthly interest

Payment $1,040; Balance $5,000

Payment 6: $5,000 × .08 = $400 annual interest; 400 ÷ 12 = $33.33

Payment $1,033.33; Balance $4,000

7 Here’s how you record the payment:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Credit Card Payable |

$200 |

|

|

Interest Expense |

$36 |

|

|

Cash |

$236 |

8 Here’s how you record the payment:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Interest Expense |

$47 |

|

|

Cash |

$47 |

9 Here’s how you record the payment:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Interest Expense |

$150 |

|

|

Cash |

$150 |

10 Here’s how you record the payment:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Line of Credit Payable$500 |

||

|

Interest Expense |

$85 |

|

|

Cash |

$585 |

11 First three months of payments:

|

Year 1 payment |

$298.65 principal |

$1,500 interest |

|

Year 2 payment |

$300.14 principal |

$1,498.51 interest |

|

Year 3 payment |

$301.65 principal |

$1,497.01 interest |

Record first payment:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Mortgages Payable |

$298.65 |

|

|

Interest Expense |

$1,500.00 |

|

|

Cash |

$1,798.65 |

12 First three months of payments:

|

Year 1 payment |

$340.24 principal |

$166.67 interest |

|

Year 2 payment |

$342.51 principal |

$164.40 interest |

|

Year 3 payment |

$344.79 principal |

$162.11 interest |

Record first payment

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

Car Loan Payable |

$340.24 |

|

Interest Expense |

$166.67 |

|

Cash |

$506.91 |

Not all accounts that earn compound interest are created equally. Watch carefully to see how frequently the interest is compounded. The preceding example shows a type of account for which interest is compounded annually. But if you can find an account where interest is compounded monthly, the interest you earn will be even higher. Monthly compounding means that interest earned is calculated each month and added to the principal each month before calculating the next month’s interest, which results in a lot more interest than a bank that compounds interest just once a year.

Not all accounts that earn compound interest are created equally. Watch carefully to see how frequently the interest is compounded. The preceding example shows a type of account for which interest is compounded annually. But if you can find an account where interest is compounded monthly, the interest you earn will be even higher. Monthly compounding means that interest earned is calculated each month and added to the principal each month before calculating the next month’s interest, which results in a lot more interest than a bank that compounds interest just once a year. In Table 13-1, the Finance Charges include the daily rate charged in interest based on the daily periodic rate plus any transaction fees. For example, if you take a cash advance from your credit card, many credit-card companies charge a transaction fee of 2 to 3 percent of the total amount of cash taken. This fee can be in effect when you transfer balances from one credit card to another. Although the company entices you with an introductory rate of 1 or 2 percent to get you to transfer the balance, be sure to read the fine print. You may have to pay a 3 percent transaction fee on the full amount transferred, which makes the introductory rate much higher.

In Table 13-1, the Finance Charges include the daily rate charged in interest based on the daily periodic rate plus any transaction fees. For example, if you take a cash advance from your credit card, many credit-card companies charge a transaction fee of 2 to 3 percent of the total amount of cash taken. This fee can be in effect when you transfer balances from one credit card to another. Although the company entices you with an introductory rate of 1 or 2 percent to get you to transfer the balance, be sure to read the fine print. You may have to pay a 3 percent transaction fee on the full amount transferred, which makes the introductory rate much higher.