Figure 14-1: QuickBooks lets you generate reports showing your company’s cash receipts organized by various categories.

Chapter 14

Proving Out the Cash

In This Chapter

Counting your company’s cash

Counting your company’s cash

Finalizing the cash journals

Finalizing the cash journals

Balancing out your bank accounts

Balancing out your bank accounts

Posting cash-related adjustments

Posting cash-related adjustments

All business owners — whether the business is a small, family-owned candy store or a major international conglomerate — like to periodically test how well their businesses are doing. They also want to be sure that the numbers in their accounting systems actually match what’s physically in their stores and offices. After they check out what’s in the books, these business owners can prepare financial reports to determine the company’s financial success or failure during the last month, quarter, or year. This process of verifying the accuracy of your cash is called proving out.

The first step in proving out the books involves counting the company’s cash and verifying that the cash numbers in your books match the actual cash on hand at a particular point in time. This chapter explains how you can test to be sure the cash counts are accurate, finalize the cash journals for the accounting period, prove out the bank accounts, and post any adjustments or corrections to the General Ledger.

Why Prove Out the Books?

You’re probably thinking that proving out the books sounds like a huge task that takes lots of time. You’re right — it’s a big job, but it’s also a very necessary one to do periodically so you can be sure that what’s recorded in your accounting system realistically measures what’s actually going on in your business.

With any accounting system, mistakes are possible, and, unfortunately, any business can fall victim to incidents of theft or embezzlement. The only way to be sure that none of these problems exists in your business is to periodically prove out the books. The process of proving out the books is a big part of the accounting cycle, which I discuss in detail in Chapter 2. The first three steps of the accounting cycle — recording transactions, making journal entries, and posting summaries of those entries to the General Ledger — involve tracking the flow of cash throughout the accounting period. The rest of the steps in the accounting cycle are conducted at the end of the period and are part of the process of proving out the accuracy of your books. They include running a trial balance and creating a worksheet (see Chapter 16), adjusting journal entries (see Chapter 17), creating financial statements (see Chapters 18 and 19), and closing the books (see Chapter 22). Most businesses prove out their books every month.

Of course, you don’t want to shut down your business for a week while you prove out the books, so you should select a day during each accounting period on which you’ll take a financial snapshot of the state of your accounts. For example, if you’re preparing monthly financial reports at the end of the month, you test the amount of cash your business has on hand as of that certain time and day, such as 6 p.m. on June 30, after your store closes for the day. The rest of the testing process — running a trial balance, creating a worksheet, adjusting journal entries, creating financial statements, and closing the books — is based on what happened before that point in time. When you open the store and sell more products the next day and buy new things to run your business, those transactions and any others that follow the point in time of your test become part of the next accounting cycle.

Making Sure Ending Cash Is Right

Testing your books starts with counting your cash. Why start with cash? Because the accounting process starts with transactions, and transactions occur when cash changes hands either to buy things you need to run the business or to sell your products or services. Before you can even begin to test whether the books are right, you need to know whether your books have captured what’s happened to your company’s cash and whether the amount of cash shown in your books actually matches the amount of cash you have on hand.

I’m sure you’ve heard the well-worn expression “Show me the money!” Well, in business, that idea is the core of your success. Everything relies on your cash profits that you can take out of your business or use to expand your business.

In Chapter 9, I discuss how a business proves out the cash taken in by each of its cashiers. That daily process gives a business good control of the point at which cash comes into the business from customers who buy the company’s products or services. It also measures any cash refunds that were given to customers who returned items. But the points of sale and return aren’t the only times cash comes into or goes out of the business.

If your business sells products on store credit (see Chapter 9), some of the cash from customers is actually collected at a later point in time by the bookkeeping staff responsible for tracking customer credit accounts. And when your business needs something, whether that’s products to sell or supplies needed by various departments, you must pay cash to vendors, suppliers, and contractors. Sometimes cash is paid out on the spot, but many times the bill is recorded in the Accounts Payable account and paid at a later date. All these transactions involve the use of cash, so the amount of cash on hand in the business at any one time includes not only what’s in the cash registers but also what’s on deposit in the company’s bank accounts. You need to know the balances of those accounts and test those balances to be sure they’re accurate and match what’s in your company’s books. I talk more about how to do that in the section “Reconciling Bank Accounts” later in this chapter.

So your snapshot in time includes not only the cash on hand in your cash registers but also any cash you may have in the bank. Some departments may also have petty cash accounts, which means you total that cash as well. The total cash figure is what you show as an asset named “Cash” on the first line of your company’s financial statement, the balance sheet. The balance sheet shows all that the company owns (its assets) and owes (its liabilities) as well as the equity the owners have in the company. (I talk more about the balance sheet and how you prepare one in Chapter 18.)

Closing the Cash Journals

As I explain in Chapter 5, if you keep the books manually, you can find a record of every transaction that involves cash in one of two cash journals: the Cash Receipts journal (cash that comes into the business) and the Cash Disbursements journal (cash that goes out of the business).

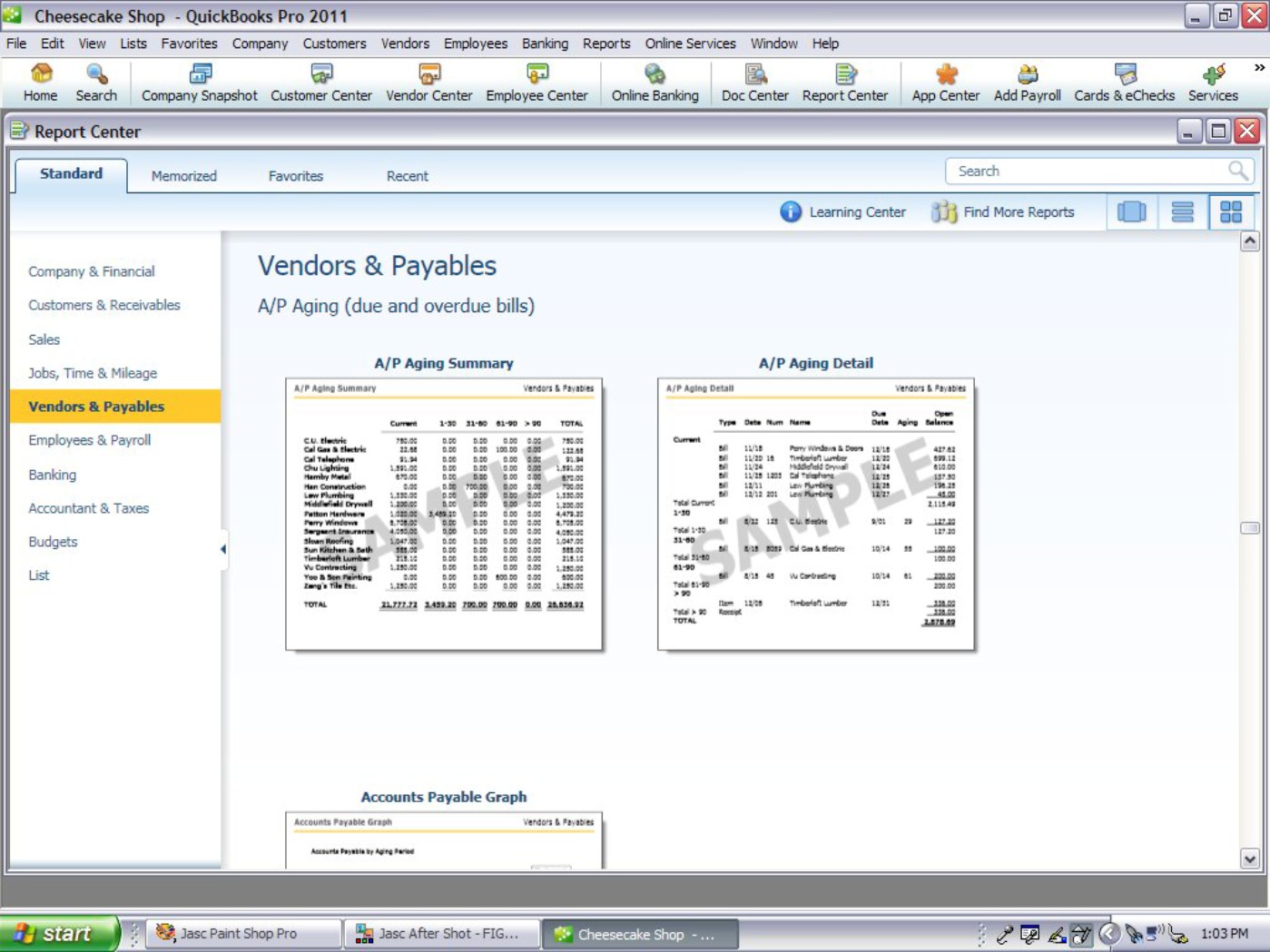

If you use a computerized accounting system, you don’t have these cash journals, but you have many different ways to find out the same detailed information as they contain. You can run reports of sales by customer, by item, or by sales representative. Figure 14-1 shows the types of sales reports that QuickBooks can automatically generate for you. You can also run reports that show you all the company’s purchases by vendor or by item as well as list any purchases still on order; you can see these kinds of QuickBooks report options in Figure 14-2. Your system can run these reports by the week, month, quarter, year, or any customized period of time that you’re analyzing. For example, if you want to know what sales occurred between June 5 and 10, you can run a report specifying those exact dates.

In addition to the sales and purchase reports shown in Figures 14-1 and 14-2, you can generate other transaction detail reports including customers and receivables; jobs, time, and mileage; vendors and payables; employees and payroll; and banking (see the options listed on the left side of Figure 14-1). One big advantage of a computerized accounting system when you’re trying to prove out your books is the number of different ways you can develop reports to check for accuracy in your books if you suspect an error.

Finalizing cash receipts

If all your books are up-to-date when you summarize the Cash Receipts journal on whatever day and time you choose to prove out your books, you should come up with a total of all cash received by the business at that time. Unfortunately, in the real world of bookkeeping, things don’t come out so nice and neat. In fact, you probably wouldn’t even start entering the transactions from that particular day into the books until the next day, when you enter the cash reports from all cashiers and others who handle incoming cash (such as the accounts receivable staff who collect money from customers buying on credit) into the Cash Receipts journal.

Image Credit: Intuit

Figure 14-2: QuickBooks lets you produce reports showing your company’s cash disbursements by vendor or by items bought.

Image Credit: Intuit

Remembering credit card fees

When your company allows customers to use credit cards, you must pay fees to the bank that processes these transactions, which is probably the same bank that handles all your business accounts. These fees actually lower the amount you take in as cash receipts, so the amount you record as a cash receipt must be adjusted to reflect those costs of doing business. Monthly credit card fees vary greatly depending on the bank you’re using, but here are some of the most common fees your bank may charge:

Address verification service (AVS) fee is a fee companies pay if they want to avoid accepting fraudulent credit card sales. Businesses that use this service take orders by phone or internet and therefore don’t have the credit card in hand to verify a customer’s signature. Banks charge this fee for every transaction that’s verified.

Address verification service (AVS) fee is a fee companies pay if they want to avoid accepting fraudulent credit card sales. Businesses that use this service take orders by phone or internet and therefore don’t have the credit card in hand to verify a customer’s signature. Banks charge this fee for every transaction that’s verified.

Discount rate is a fee all companies that use credit cards must pay; it’s based on a percentage of the sale or return transaction. The rate your company may be charged varies greatly depending on the type of business you conduct and the volume of your sales each month. Companies that use a terminal to swipe cards and electronically send transaction information usually pay lower fees than companies that use paper credit card transactions because the electronic route creates less work for the bank and eliminates the possibility of key-entry errors by employees.

Discount rate is a fee all companies that use credit cards must pay; it’s based on a percentage of the sale or return transaction. The rate your company may be charged varies greatly depending on the type of business you conduct and the volume of your sales each month. Companies that use a terminal to swipe cards and electronically send transaction information usually pay lower fees than companies that use paper credit card transactions because the electronic route creates less work for the bank and eliminates the possibility of key-entry errors by employees.

Secure payment gateway fee, which allows the merchant to process transactions securely, is charged to companies that transact business over the Internet. If your business sells products online, you can expect to pay this set monthly fee.

Secure payment gateway fee, which allows the merchant to process transactions securely, is charged to companies that transact business over the Internet. If your business sells products online, you can expect to pay this set monthly fee.

Customer support fee is charged to companies that want bank support for credit card transactions for 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Companies such as mail-order catalogs that allow customers to place orders 24 hours a day look for this support. Sometimes companies even want this support in more than one language if they sell products internationally.

Customer support fee is charged to companies that want bank support for credit card transactions for 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Companies such as mail-order catalogs that allow customers to place orders 24 hours a day look for this support. Sometimes companies even want this support in more than one language if they sell products internationally.

Monthly minimum fee is the least a business is required to pay for the ability to offer its customers the convenience of using credit cards to buy products. This fee usually varies between $10 and $30 per month.

Monthly minimum fee is the least a business is required to pay for the ability to offer its customers the convenience of using credit cards to buy products. This fee usually varies between $10 and $30 per month.

Even if your company doesn’t generate any credit card sales during a month, you’re still required to pay this minimum fee. As long as you generate enough sales to cover the fee, you shouldn’t have a problem. For example, if the fee is $10 and your company pays 2 percent per sale in discount fees, you need to sell at least $500 worth of products each month to cover that $10 fee. When deciding whether to accept credit cards as a payment option, be sure you’re confident that you’ll generate enough business through credit card sales to cover that fee. If not, you may find that accepting credit cards costs you more than the sales you generate by offering that convenience.

Even if your company doesn’t generate any credit card sales during a month, you’re still required to pay this minimum fee. As long as you generate enough sales to cover the fee, you shouldn’t have a problem. For example, if the fee is $10 and your company pays 2 percent per sale in discount fees, you need to sell at least $500 worth of products each month to cover that $10 fee. When deciding whether to accept credit cards as a payment option, be sure you’re confident that you’ll generate enough business through credit card sales to cover that fee. If not, you may find that accepting credit cards costs you more than the sales you generate by offering that convenience.

Transaction fee is a standard fee charged to your business for each credit card transaction you submit for authorization. You pay this fee even if the cardholder is denied and you lose the sale.

Transaction fee is a standard fee charged to your business for each credit card transaction you submit for authorization. You pay this fee even if the cardholder is denied and you lose the sale.

Equipment and software fees are charged to your company based on the equipment and computer software you use in order to process credit card transactions. You have the option of buying or leasing credit card equipment and related software.

Equipment and software fees are charged to your company based on the equipment and computer software you use in order to process credit card transactions. You have the option of buying or leasing credit card equipment and related software.

Chargeback and retrieval fees are charged if a customer disputes a transaction.

Chargeback and retrieval fees are charged if a customer disputes a transaction.

Reconciling your credit card statements

Each month, the bank that handles your credit card sales will send you a statement listing

All your company’s transactions for the month

All your company’s transactions for the month

The total amount your company sold through credit card sales

The total amount your company sold through credit card sales

The total fees charged to your account

The total fees charged to your account

If you find a difference between what the bank reports was sold on credit cards and what the company’s books show regarding credit card sales, it’s time to play detective and find the reason for the difference. In most cases, the error involves the charging back of one or more sales because a customer disputes the charge. In this case, the Cash Receipts journal is adjusted to reflect that loss of sale, and the bank statement and company books should match up.

For example, suppose $200 in credit card sales were disputed. The original entry of the transaction in the books should look like this:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Sales |

$200 |

|

|

Cash |

$200 |

|

|

To reverse disputed credit sales recorded in June. |

||

This entry reduces the total Sales for the month as well as the amount of the Cash account. If the dispute is resolved and the money is later retrieved, the sale is then reentered when the cash is received.

You also record any fees related to credit card fees in the Cash Disbursements journal. For example, if credit card fees for the month of June total $200, the entry in the books should look like this:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Credit Card Fees |

$200 |

|

|

Cash |

$200 |

|

|

To reverse credit card fees for the month of June. |

||

Summarizing the Cash Receipts journal

When you’re sure that all cash receipts as well as any corrections or adjustments to those receipts have been properly entered in the books (see the preceding two sections), you summarize the Cash Receipts journal as I explain in detail in Chapter 5. After summarizing the Cash Receipts journal for the accounting period you’re analyzing, you know the total cash that was taken into the business from sales as well as from other channels.

In the Cash Receipts journal, sales usually appear in two columns:

Sales: The cash shown in the Sales column is cash received when the customer purchases the goods by using cash, check, or bank credit card.

Sales: The cash shown in the Sales column is cash received when the customer purchases the goods by using cash, check, or bank credit card.

Accounts Receivable: The Accounts Receivable column is for sales in which no cash was received when the customer purchased the item. Instead, the customer bought on credit and intends to pay cash at a later date. (I talk more about Accounts Receivable and collecting money from customers in Chapter 9.)

Accounts Receivable: The Accounts Receivable column is for sales in which no cash was received when the customer purchased the item. Instead, the customer bought on credit and intends to pay cash at a later date. (I talk more about Accounts Receivable and collecting money from customers in Chapter 9.)

After you add all receipts to the Cash Receipts journal, entries for items bought on store credit can be posted to the Accounts Receivable journal and the individual customer accounts. You then send bills to customers that reflect all transactions from the month just closed as well as any payments still due from previous months. Billing customers is a key part of the closing process that occurs each month.

In addition to the Sales and Accounts Receivable columns, your Cash Receipts journal should have at least two other columns:

General: The General column lists all other cash received, such as owner investments in the business.

General: The General column lists all other cash received, such as owner investments in the business.

Cash: The Cash column contains the total of all cash received by the business during an accounting period.

Cash: The Cash column contains the total of all cash received by the business during an accounting period.

Finalizing cash outlays

After you close the Cash Receipts journal (see “Summarizing the Cash Receipts journal”), the next step is to close the Cash Disbursements journal. Add any adjustments related to outgoing cash receipts, such as bank credit card fees, to the Cash Disbursements journal. Before you close the journal, you must also be certain that any bills paid at the end of the month have been added to the Cash Disbursements journal.

Bills that are related to financial activity for the month being closed but that haven’t yet been paid have to be accrued, which means recorded in the books, so they can be matched to the revenue for the month. These accruals are only necessary if you use the accrual accounting method. If you use the cash-basis accounting method, you need to record the bills only when cash is actually paid. For more on the accrual and cash-basis methods, flip to Chapter 2.

You accrue bills yet to be paid in the Accounts Payable account. For example, suppose that your company prints and mails fliers to advertise a sale during the last week of the month. A bill for the fliers totaling $500 hasn’t been paid yet. Here’s how you enter the bill in the books:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Advertising |

$500 |

|

|

Accounts Payable |

$500 |

|

|

To accrue the bill from Jack’s printing for June sales flyers. |

||

This entry increases advertising expenses for the month and increases the amount due in Accounts Payable. When you pay the bill, the Accounts Payable account is debited (to reduce the liability), and the Cash account is credited (to reduce the amount in the cash account). You make the actual entry in the Cash Disbursements journal when the cash is paid out.

Practice: Closing the Cash Journals

Q. When you get the credit card statement at the end of May, you see a total of $125 in fees for the month and find that one customer disputed a charge of $35. How do you make those adjustments in the Cash journals?

A. You make two adjusting entries — one to reverse the sale recorded in the Cash Receipts journal and one to record the fees in the Cash Disbursements journal. The credits reduce the amount of cash in the books. The cash has already been subtracted from your bank account. So you must reconcile what’s in your books with what’s in your bank account.

You make this entry in your Cash Receipts journal to reverse the sale:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Sales |

$35 |

|

|

Cash |

$35 |

You make this entry in your Cash Disbursements journal to record the fees:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Credit Card Fees |

$125 |

|

|

Cash |

$125 |

1. When you get your credit card statement, you see a total of $225 in fees and you find three chargebacks for customer disputes totaling $165. How do you record this information in your books?

Solve It

2. When you get your credit card statement, you find $320 in fees and a total of $275 in chargebacks from customer disputes. How do you record this information in your books?

Solve It

3. You receive a bill for $2,500 for advertising during the month of June on June 30. You don’t have to pay the bill until July. How and when do you record the bill? You use the accrual method of accounting.

Solve It

4. You receive a bill for $375 for office supplies for the month of May on May 30. You don’t have to pay the bill until June 10, but the supplies were used primarily in May. How and when do you record the bill? You use the accrual method of accounting.

Solve It

Using a Temporary Posting Journal

Some companies use a Temporary Posting journal to record payments that are made without full knowledge of how the cash outlay should be posted to the books and which accounts will be impacted. For example, a company using a payroll service probably has to give that service a certain amount of cash to cover payroll even if it doesn’t exactly know yet how much is needed for taxes and other payroll-related costs.

In this payroll example, cash must be disbursed, but transactions can’t be entered into all affected accounts until the payroll is done. Suppose a company’s payroll is estimated to cost $15,000 for the month of May. The company sends a check to cover that cost to the payroll service and posts the payment to the Temporary Posting journal, and after the payroll is calculated and completed, the company receives a statement of exactly how much was paid to employees and how much was paid in taxes. After the statement arrives, allocating the $15,000 to specific accounts such as Payroll Expenses or Tax Expenses, that information is posted to the Cash Disbursements journal.

Reconciling Bank Accounts

Part of proving out cash involves checking that what you have in your bank accounts actually matches what the bank thinks you have in those accounts. This process is called reconciling the accounts.

Before you tackle reconciling your accounts with the bank’s records, it’s important to be sure that you’ve made all necessary adjustments to your books. When you make adjustments to your cash accounts, you identify and correct any cash transactions that may not have been properly entered into the books. You also make adjustments to reflect interest income or payments, bank fees, and credit card chargebacks.

If you’ve done everything right, your accounting records should match the bank’s records when it comes to how much cash you have in your accounts. The day you close your books probably isn’t the same date as the bank sends its statements, so do your best at balancing the books internally without actually reconciling your checking account. Correcting any problems during the process of proving out will minimize problems you may face reconciling the cash accounts when that bank statement actually does arrive.

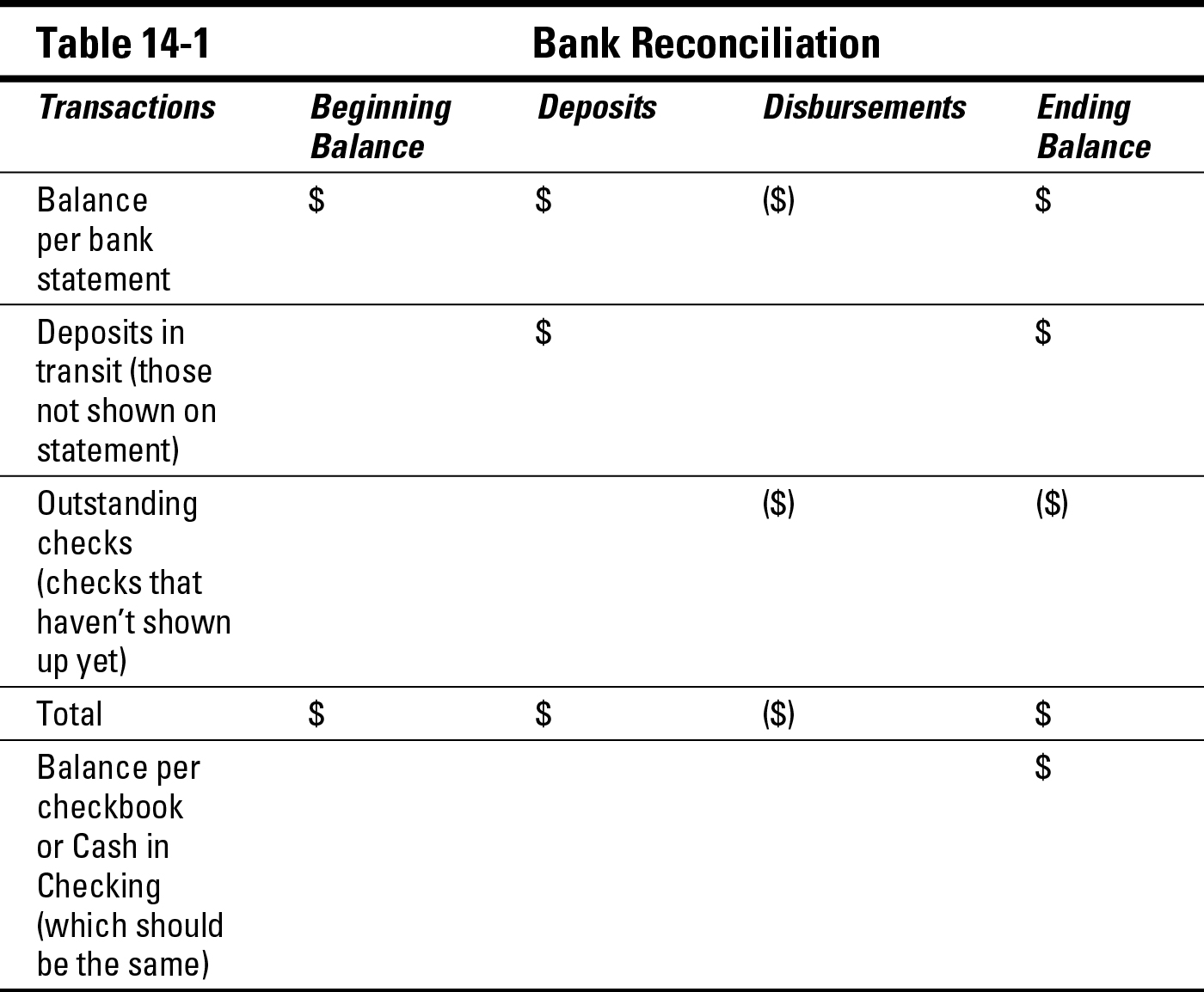

You’ve probably reconciled your personal checking account at least a few times over the years, and you’ll be happy to hear that reconciling business accounts is a similar process. Table 14-1 shows one common format for reconciling your bank account:

Tracking down errors

Ideally, your balance and the bank’s balance adjusted by transactions not yet shown on the statement should match. If they don’t, you need to find out why.

If the bank balance is higher than your balance, check to be sure that all the deposits listed by the bank appear in the Cash account in your books. If you find that the bank lists a deposit that you don’t have, you need to do some detective work to figure out what that deposit was for and add the detail to your accounting records. Also, check to be sure that all checks have cleared. Your balance may be missing a check that should have been listed in outstanding checks.

If the bank balance is higher than your balance, check to be sure that all the deposits listed by the bank appear in the Cash account in your books. If you find that the bank lists a deposit that you don’t have, you need to do some detective work to figure out what that deposit was for and add the detail to your accounting records. Also, check to be sure that all checks have cleared. Your balance may be missing a check that should have been listed in outstanding checks.

If the bank balance is lower than your balance, check to be sure that all checks listed by the bank are recorded in your Cash account. You may have missed one or two checks that were written but not properly recorded. You also may have missed a deposit that you have listed in your Cash account and you thought the bank already should have shown as a deposit, but it wasn’t yet on the statement. If you notice a missing deposit on the bank statement, be sure you have your proof of deposit and check with the bank to be sure the cash is in the account.

If the bank balance is lower than your balance, check to be sure that all checks listed by the bank are recorded in your Cash account. You may have missed one or two checks that were written but not properly recorded. You also may have missed a deposit that you have listed in your Cash account and you thought the bank already should have shown as a deposit, but it wasn’t yet on the statement. If you notice a missing deposit on the bank statement, be sure you have your proof of deposit and check with the bank to be sure the cash is in the account.

If all deposits and checks are correct but you still see a difference, your only option is to check your math and make sure all checks and deposits were entered correctly.

If all deposits and checks are correct but you still see a difference, your only option is to check your math and make sure all checks and deposits were entered correctly.

Using a computerized system

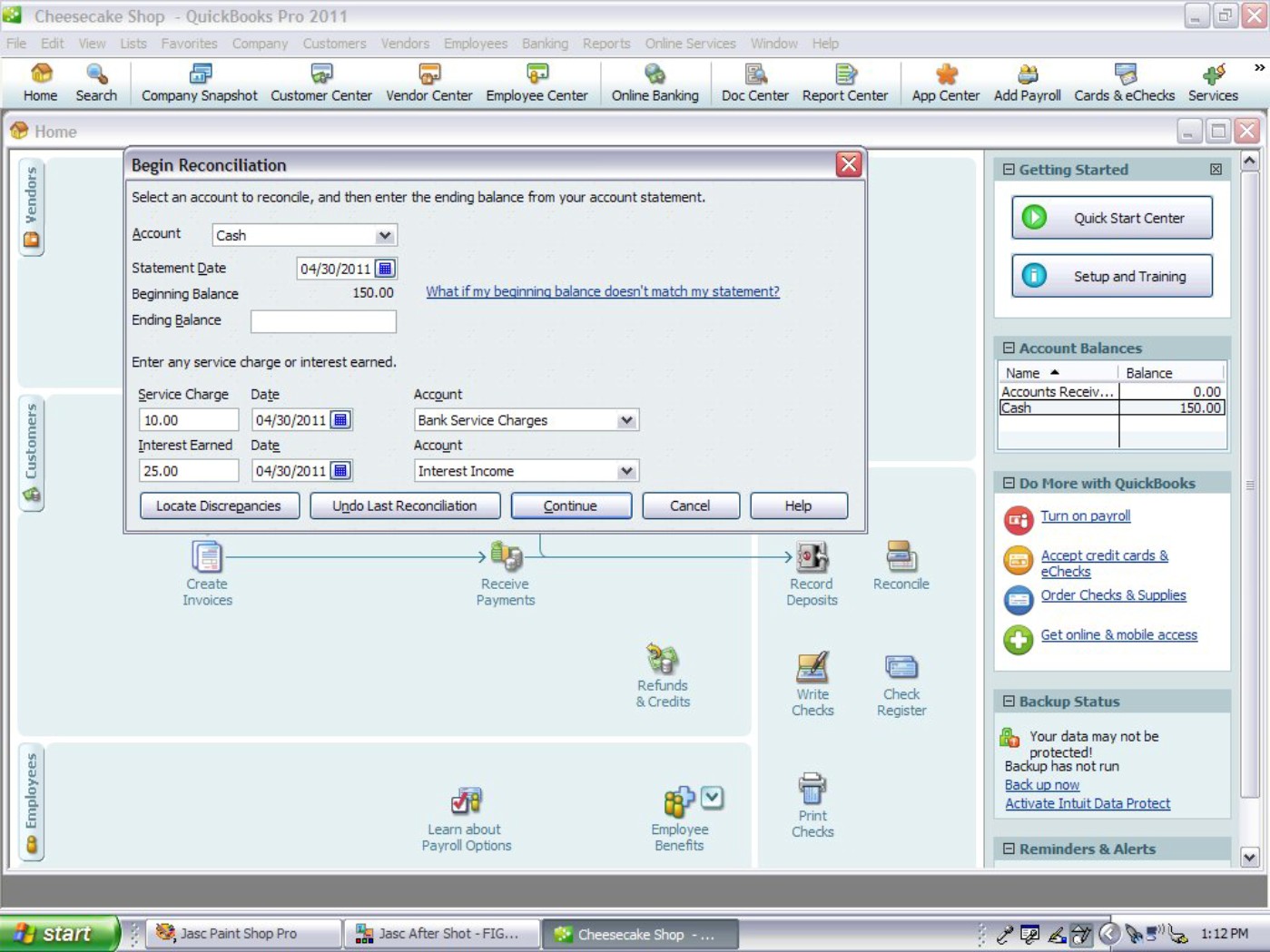

If you use a computerized accounting system, reconciliation should be much easier than if you keep your books manually. In QuickBooks, for example, when you start the reconciliation process, a screen opens in which you can add the ending bank statement balance and any bank fees or interest earned. Figure 14-3 shows you the first screen in the reconciliation process. (The bank fees are automatically added to the bank fees expense account.)

After you click on Continue, you get a screen that lists all checks written since the last reconciliation, as well as all deposits (see Figure 14-4). You put a check mark next to the checks and deposits that have cleared on the bank statement and then click on Reconcile Now.

QuickBooks automatically reconciles the accounts and provides reports that indicate any differences. It also provides a reconciliation summary, shown in Figure 14-5, that includes the beginning balance, the balance after all cleared transactions have been recorded, and a list of all uncleared transactions. QuickBooks also calculates what your check register should show when the uncleared transactions are added to the cleared transactions.

Figure 14-3: Part one of the reconciliation process in QuickBooks.

Image Credit: Intuit

Figure 14-4: Put a check mark next to all the checks and deposits that have cleared the account and click on Reconcile Now.

Image Credit: Intuit

Figure 14-5: After reconciling your accounts, QuickBooks automatically provides a reconciliation summary.

Image Credit: Intuit

Posting Adjustments and Corrections

After you close out the Cash Receipts and Cash Disbursements journals as well as reconcile the bank account with your accounting system, you post any adjustments or corrections that you uncover to any other journals that may be impacted by the change, such as the Accounts Receivable or Accounts Payable. If you make changes that don’t impact any journal accounts, you post them directly to the General Ledger.

For example, if you find that several customer payments haven’t been entered in the Cash Receipts journal, you also need to post those payments to the Accounts Receivable journal and the customers’ accounts. The same is true if you find payments on outstanding bills that haven’t been entered into the books. In this case, you post the payments to the Accounts Payable journal as well as to the individual vendors’ accounts.

Answers to Problems on Proving Out the Cash

1 The entry for the Cash Disbursements journal is

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Credit Card Fees |

$225 |

|

|

Cash |

$225 |

The entry for the Cash Receipts journal is

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Sales |

$165 |

|

|

Cash |

$165 |

2 The entry for the Cash Disbursements journal is

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Credit Card Fees |

$320 |

|

|

Cash |

$320 |

The entry for the Cash Receipts Journal is

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Sales |

$275 |

|

|

Cash |

$275 |

3 You need to enter the bill before closing the books for June, so you record the expenses against June’s receipts. The journal entry is

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Advertising Expense |

$2,500 |

|

|

Accounts Payable |

$2,500 |

4 You need to enter the bill before closing the books for May, so you record the expenses against May’s receipts. The journal entry is

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Office Supplies Expense |

$375 |

|

|

Accounts Payable |

$375 |

The actual cash you have on hand is just one tiny piece of the cash moving through your business during the accounting period. The true detail of what cash has flowed into and out of the business is in your cash journals. Closing those records are the next step in the process of figuring out how well your business did.

The actual cash you have on hand is just one tiny piece of the cash moving through your business during the accounting period. The true detail of what cash has flowed into and out of the business is in your cash journals. Closing those records are the next step in the process of figuring out how well your business did. If you decide to keep a Temporary Posting journal to track cash coming in or going out, before summarizing your Cash Disbursements journal and closing the books for an accounting period, be sure to review the transactions listed in this journal that may need to be posted in the Cash Disbursements journal.

If you decide to keep a Temporary Posting journal to track cash coming in or going out, before summarizing your Cash Disbursements journal and closing the books for an accounting period, be sure to review the transactions listed in this journal that may need to be posted in the Cash Disbursements journal.