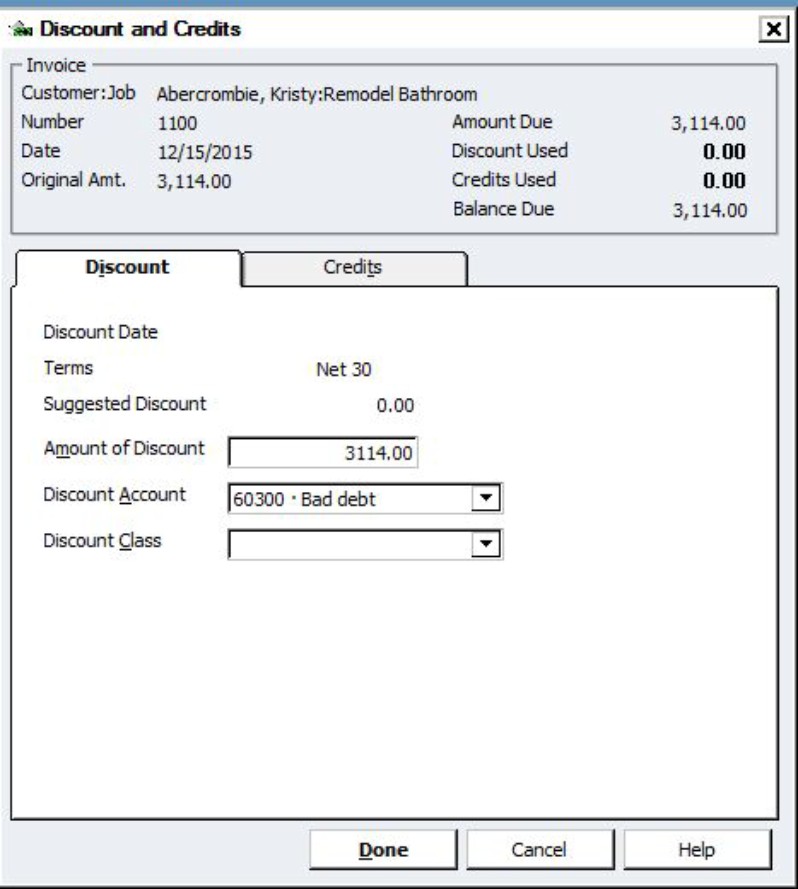

Figure 17-1: In Quick-Books, you record bad debts on the Discount and Credits page, which is part of the Customer Payment function.

Chapter 17

Adjusting the Books

In This Chapter

Making adjustments for non-cash transactions

Making adjustments for non-cash transactions

Taking your adjustments for a trial (balance) run

Taking your adjustments for a trial (balance) run

Adding to and deleting from the Chart of Accounts

Adding to and deleting from the Chart of Accounts

During an accounting period, your bookkeeping duties focus on your business’s day-to-day transactions. When it comes time to report those transactions in financial statements, you must make some adjustments to your books. Your financial reports are supposed to show your company’s financial health, so your books must reflect any significant change in the value of your assets, even if that change doesn’t involve the exchange of cash.

This chapter reviews the types of adjustments you need to make to the books before preparing the financial statements, including calculating asset depreciation, dividing up prepaid expenses, updating inventory numbers, dealing with bad debt, and recognizing salaries and wages not yet paid. You also find out how to add and delete accounts.

Adjusting All the Right Areas

Even after testing your books by using the trial balance process I explain in Chapter 16, you still need to make some adjustments before you’re able to prepare accurate financial reports with the information you have. These adjustments don’t involve the exchange of cash but rather involve recognizing the use of assets, loss of assets, or future asset obligations that aren’t reflected in day-to-day bookkeeping activities.

The key areas in which you likely need to adjust the books include the following:

Asset depreciation: To recognize the use of assets during the accounting period.

Asset depreciation: To recognize the use of assets during the accounting period.

Prepaid expenses: To match a portion of expenses that were paid at one point during the year even though benefits from that payment are used throughout the year, such as an annual insurance premium. The benefit should be apportioned out against expenses for each month.

Prepaid expenses: To match a portion of expenses that were paid at one point during the year even though benefits from that payment are used throughout the year, such as an annual insurance premium. The benefit should be apportioned out against expenses for each month.

Inventory: To update inventory to reflect what you have on hand.

Inventory: To update inventory to reflect what you have on hand.

Bad debts: To acknowledge that some customers will never pay and to write off those accounts.

Bad debts: To acknowledge that some customers will never pay and to write off those accounts.

Unpaid salaries and wages: To recognize salary and wage expenses that have been incurred but not yet paid.

Unpaid salaries and wages: To recognize salary and wage expenses that have been incurred but not yet paid.

Depreciating assets

The largest non-cash expense for most businesses is depreciation. Depreciation is an accounting exercise that’s important for every business to undertake because it reflects the use and aging of assets. Older assets need more maintenance and repair and also need to be replaced eventually. As the depreciation of an asset increases and the value of the asset dwindles, the need for more maintenance or replacement becomes apparent. (For more on depreciation and why you do it, check out Chapter 12.)

The time to actually make this adjustment to the books is when you close the books for an accounting period. (Some businesses record depreciation expenses every month to more accurately match monthly expenses with monthly revenues, but most business owners worry about depreciation adjustments on a yearly basis only, when they prepare their annual financial statements.)

Readers of your financial statements can get a good idea of the health of your assets by reviewing your accumulated depreciation. If a financial report reader sees that assets are close to being fully depreciated, he knows that you’ll probably need to spend significant funds on replacing or repairing those assets sometime soon. As he evaluates the financial health of the company, he takes that future obligation into consideration before making a decision to loan money to the company or possibly invest in it.

Usually, you calculate depreciation for accounting purposes by using the Straight-Line depreciation method. This method is used to calculate an amount to be depreciated that will be equal each year based on the anticipated useful life of the asset. For example, suppose your company purchases a car for business purposes that costs $25,000. You anticipate that car will have a useful lifespan of five years and will be worth $5,000 after five years. This post-lifespan value is known as the salvage value. Using the Straight-Line depreciation method, you subtract $5,000 from the total car cost of $25,000 to find the value of the car during its five-year useful lifespan ($20,000). Then, you divide $20,000 by 5 to find your depreciation expense for the car ($4,000 per year). When you’re adjusting the assets at the end of each year in the car’s five-year lifespan, your entry to the books should look like this:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Depreciation Expense |

$4,000 |

|

|

Accumulated Depreciation: Vehicles |

$4,000 |

|

|

To record depreciation for Vehicles. |

||

This entry increases depreciation expenses, which appear on the income statement (see Chapter 19). The entry also increases Accumulated Depreciation, which is the use of the asset and appears on the balance sheet directly under the Vehicles asset line. The Vehicle asset line always shows the value of the asset at the time of purchase.

If you use a computerized accounting system as opposed to keeping your books manually, you may or may not need to make this adjustment at the end of an accounting period. If your system is set up with an asset management feature, depreciation is automatically calculated, and you don’t have to worry about it. Check with your accountant (he or she is the one who’d set up the asset management feature) before calculating and recording depreciation expenses.

Allocating prepaid expenses

Most businesses have to pay certain expenses at the beginning of the year even though they will benefit from that expense throughout the year. Insurance is a prime example of this type of expense. Most insurance companies require you to pay the premium annually at the start of the year even though the value of that insurance protects the company throughout the year.

For example, suppose your company’s annual car insurance premium is $1,200. You pay that premium in January in order to maintain insurance coverage throughout the year. Showing the full cash expense of your insurance when you prepare your January financial reports would greatly reduce any profit that month and make your financial results look worse than the actually are. That’s no good.

Instead, you record a large expense such as insurance or prepaid rent as an asset called Prepaid Expenses, and then you adjust the value of that asset to reflect that it’s being used up. Your $1,200 annual insurance premium is actually valuable to the company for 12 months, so you calculate the actual expense for insurance by dividing $1,200 by 12, giving you $100 per month. At the end of each month, you record the use of that asset by preparing an adjusting entry that looks like this:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Insurance Expenses |

$100 |

|

|

Prepaid Expenses |

$100 |

|

|

To record insurance expenses for March. |

||

This entry increases insurance expenses on the income statement and decreases the asset Prepaid Expenses on the balance sheet. No cash changes hands in this entry because cash was laid out when the insurance bill was paid, and the asset account Prepaid Expenses was increased in value at the time the cash was paid.

Counting inventory

Inventory is a balance sheet asset that you need to adjust at the end of an accounting period. During the accounting period, your company buys inventory and records those purchases in a Purchases account without indicating any change to inventory. When the products are sold, you record the sales in the Sales account but don’t make any adjustment to the value of the inventory. Instead, you adjust the inventory value at the end of the accounting period because adjusting with each purchase and sale would be much too time-consuming.

The steps for making proper adjustments to inventory in your books are as follows:

1. Determine the inventory remaining.

In addition to calculating ending inventory by using the purchases and sales numbers in the books, you should also do a physical count of inventory to be sure that what’s on the shelves matches what’s in the books.

2. Set a value for that inventory.

The value of ending inventory varies depending on the method your company has chosen to use for valuing inventory. I talk more about inventory value and how to calculate the value of ending inventory in Chapter 8.

3. Adjust the number of pieces remaining in inventory in the Inventory Account and adjust the value of that account based on the information collected in Steps 1 and 2.

If you track inventory with your computerized accounting system, the system makes adjustments to inventory as you record sales. At the end of the accounting period, the value of your company’s ending inventory should be adjusted in the books already. Although the work’s already done for you, you should still do a physical count of the inventory to be sure that your computer records match the physical inventory at the end of the accounting period.

Allowing for bad debts

No company likes to accept the fact that it will never see the money owed by some of its customers, but in reality, that’s what happens to most companies that sell items on store credit. When your company determines that a customer who has bought products on store credit will never pay for them, you record the value of that purchase as a bad debt. (For an explanation of store credit, check out Chapter 9.)

At the end of an accounting period, you should list all outstanding customer accounts in an aging report, which I cover in Chapter 9. This report shows which customers owe how much and for how long. After a certain amount of time, you have to admit that some customers simply aren’t going to pay. Each company sets its own determination of how long it wants to wait before tagging an account as a bad debt. For example, your company may decide that when a customer is six months late with a payment, you’re unlikely to ever see the money.

After you determine that an account is a bad debt, you should no longer include its value as part of your assets in Accounts Receivable. Including its value doesn’t paint a realistic picture of your situation for the readers of your financial reports. Because the bad debt is no longer an asset, you adjust the value of your Accounts Receivable to reflect the loss of that asset.

You can record bad debts in a couple of ways:

By customer: Some companies identify the specific customers whose accounts are bad debts and calculate the bad debt expense each accounting period based on specified customers’ accounts.

By customer: Some companies identify the specific customers whose accounts are bad debts and calculate the bad debt expense each accounting period based on specified customers’ accounts.

By percentage: Other companies look at their bad-debts histories and develop percentages that reflect those experiences. Instead of taking the time to identify each specific account that will be a bad debt, these companies record bad debt expenses as a percentage of their Accounts Receivable.

By percentage: Other companies look at their bad-debts histories and develop percentages that reflect those experiences. Instead of taking the time to identify each specific account that will be a bad debt, these companies record bad debt expenses as a percentage of their Accounts Receivable.

However you decide to record bad debts, you need to prepare an adjusting entry at the end of each accounting period to record bad debt expenses. Here’s an adjusting entry to record bad debt expenses of $1,000:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Bad Debt Expense |

$1,000 |

|

|

Accounts Receivable |

$1,000 |

|

|

To write off customer accounts. |

||

If you use a computerized accounting system, check the system’s instructions for how to write off bad debts. To write off a bad debt in QuickBooks, follow these steps:

1. Open the screen where you normally record customer payments, and enter “$0” instead of entering the amount received in payment.

2. Place a check mark next to the amount being written off.

3. Click Discount and Credits at the bottom-right part of the screen to open that window and see the amount due.

4. On the Discount tab, which is shown in Figure 17-1, type in the amount of the discount.

5. Select Bad Debt from the Discount Account menu.

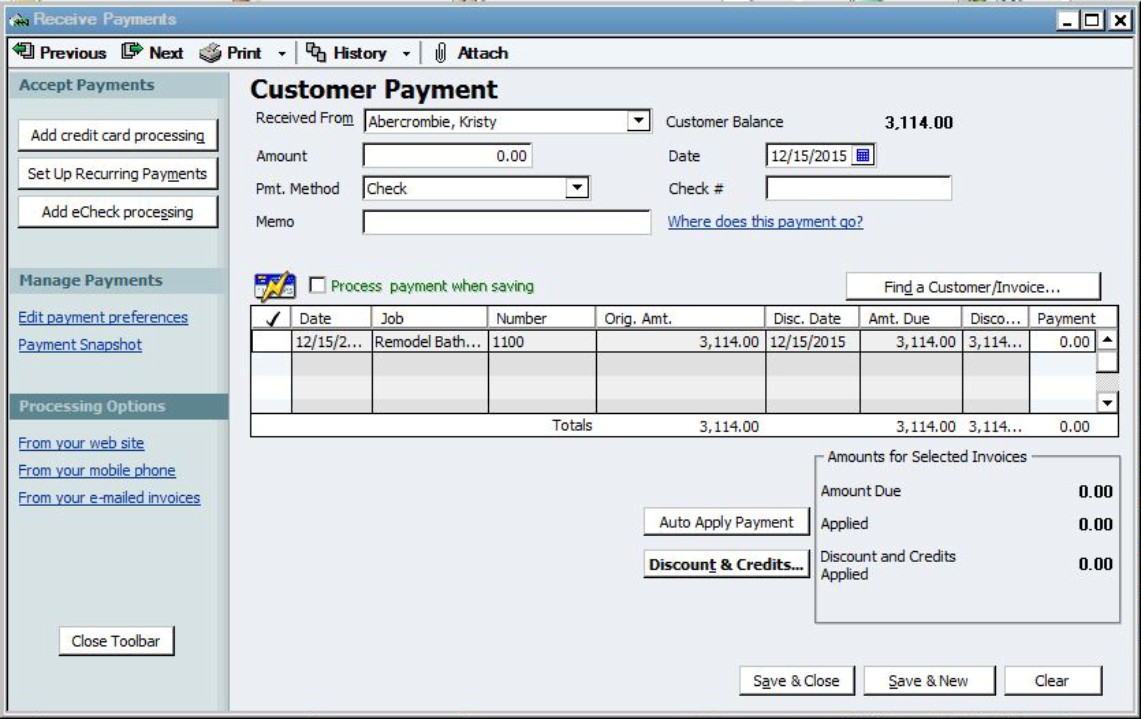

6. Click Done and verify that the discount is applied and no payment is due (see Figure 17-2).

Image Credit: Intuit

Figure 17-2: After you record a bad debt in QuickBooks, the discount appears, indicating that $0 is due.

Image Credit: Intuit

Recognizing unpaid salaries and wages

Not all pay periods fall at the end of a month. If you pay your employees every two weeks, you may end up closing the books in the middle of a pay period, meaning that, for example, employees aren’t paid for the last week of March until the end of the first week of April.

When your pay period hits before the end of the month, you need to make an adjusting entry to record the payroll expense that has been incurred but not yet paid. You estimate the amount of the adjustment based on what you pay every two weeks. The easiest thing to do is just accrue the expense of half of your payroll (which means you enter the anticipated expense as an accrual in the appropriate account; when the cash is actually paid out, you then reverse that accrual entry, which reduces the amount in the liability account, Accrued Payroll expenses, and the Cash account, to reflect the outlay of cash). If that expense is $3,000, you make the following adjusting entry to the books to show the accrual:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Payroll Expenses |

$3,000 |

|

|

Accrued Payroll Expenses |

$3,000 |

|

|

To record payroll expenses for the last week of March. |

||

This adjusting entry increases both the Payroll Expenses reported on the income statement and the Accrued Payroll Expenses that appear as a liability on the balance sheet. The week’s worth of unpaid salaries and wages is actually a liability that you will have to pay in the future even though you haven’t yet spent the cash. When you finally do pay out the salaries and wages, you reduce the amount in Accrued Payroll Expenses with the following entry:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Accrued Payroll Expenses |

$3,000 |

|

|

Cash |

$3,000 |

|

|

To record the cash payment of salaries and wages for the last week of March. |

||

Note that when the cash is actually paid, you don’t record any expenses; instead, you decrease the Accrued Payroll Expense account, which is a liability. The Cash account, which is an asset, also decreases.

Doing these extra entries may seem like a lot of extra work, but if you don’t match the payroll expenses for March with the revenues for March, your income statements won’t reflect the actual state of your affairs. Your revenues at the end of March will look very good because your salary and wage expenses aren’t fully reflected in the income statement, but your April income statement will look very bad given the extra expenses that were actually incurred in March.

Practice: Adjusting for Certain Expenses and Inventory

Q. At the end of the month, you find that you have $10,000 of inventory remaining. You started the month with $9,500. What adjusting entry do you make to the books?

A. You first need to calculate the difference and determine whether you ended up with additional inventory, which means you purchased inventory that you didn’t use that month. If that’s the case, you then need to prepare an adjusting entry to increase the asset inventory, and you need to decrease your Purchases Expenses because those purchases will be sold in the next month.

In this case, you find that you have $500 more in inventory, so here’s the adjusting entry you need to make:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Inventory |

$500 |

|

|

Purchases Expense |

$500 |

This entry increases the Inventory account on the Balance Sheet and decreases the Purchases Expense account on the Income Statement.

1. Your company owns a copier with a cost basis of $30,000 and a salvage value of $0. Assume a useful life of five years. How much do you record for depreciation expenses for the year? What’s your adjusting entry?

Solve It

2. Your company owns a building with a cost basis of $300,000 and a salvage value of $50,000. Assume a useful life of 39 years. How much do you record for depreciation expenses for the year? What’s your adjusting entry?

Solve It

3. Your offices have furniture with a cost basis of $200,000 and a salvage value of $50,000. Assume a useful life of seven years. How much do you record for depreciation expenses for the year? What’s your adjusting entry?

Solve It

4. Suppose your company pays $10,500 semiannually for insurance on all its vehicles. You’re closing the books for the month of May. What adjusting entry do you need to make?

Solve It

5. Suppose your company pays $12,000 quarterly for rent on its retail outlet. You’re closing the books for the month of May. What adjusting entry do you need to make?

Solve It

6. At the end of the month, you find that you have $9,000 in ending inventory. You started the month with $8,000 in inventory. What adjusting entry do you make to the books?

Solve It

7. At the end of the month, you calculate your ending inventory and find that its value is $250 more than your beginning inventory value, which means you purchased inventory during the month that wasn’t used. What adjusting entry do you make to the books?

Solve It

8. You identify six customers whose payments are more than six months late, and the total amount due from those customers is $2,000. What adjusting entry do you make to the books?

Solve It

9. Your company has determined that historically, 5 percent of its Accounts Receivable never gets paid. What adjusting entry do you make to the books if your Accounts Receivable at the end of the month is $10,000?

Solve It

10. Your payroll for the last full week in May is $10,000, but it won’t be paid until June. How do you initially enter this transaction in the books? How do you enter it when the cash is actually paid out? Assume the payroll for the first full week of June is the same amount.

Solve It

11. Your payroll for the last four days of May won’t be paid until June 8. The biweekly payroll totals $5,000, and each work week is five days. How much do you record for the payroll expenses for May? What does the entry look like when you initially enter it into the books? When the cash is actually paid out?

Solve It

Testing Out an Adjusted Trial Balance

In Chapter 16, I explain why and how you run a trial balance on the accounts in your General Ledger. Adjustments to your books call for another trial balance, the adjusted trial balance, to ensure that your adjustments are correct and ready to be posted to the General Ledger.

You track all the adjusting entries on a worksheet similar to the one shown in Chapter 16. You need to do this worksheet only if you’re doing your books manually. It’s not necessary if you’re using a computerized accounting system.

The key difference in the worksheet for the Adjusted Trial Balance is that four additional columns must be added to the worksheet for a total of 11 columns. Columns include

Column 1: Account titles.

Column 1: Account titles.

Columns 2 and 3: Unadjusted Trial Balance. The trial balance before the adjustments are made with Column 2 for debits and Column 3 for credits.

Columns 2 and 3: Unadjusted Trial Balance. The trial balance before the adjustments are made with Column 2 for debits and Column 3 for credits.

Columns 4 and 5: Adjustments. All adjustments to the trial balance are listed in Column 4 for debits and Column 5 for credits.

Columns 4 and 5: Adjustments. All adjustments to the trial balance are listed in Column 4 for debits and Column 5 for credits.

Columns 6 and 7: Adjusted Trial Balance. A new trial balance is calculated that includes all the adjustments. Be sure that the credits equal the debits when you total that new Trial Balance. If they don’t, find any errors before adding entries to the balance sheet and income statement columns.

Columns 6 and 7: Adjusted Trial Balance. A new trial balance is calculated that includes all the adjustments. Be sure that the credits equal the debits when you total that new Trial Balance. If they don’t, find any errors before adding entries to the balance sheet and income statement columns.

Columns 8 and 9: Balance sheet. Column 8 includes all the balance sheet accounts that have a debit balance, and Column 9 includes all the balance sheet accounts with a credit balance.

Columns 8 and 9: Balance sheet. Column 8 includes all the balance sheet accounts that have a debit balance, and Column 9 includes all the balance sheet accounts with a credit balance.

Columns 10 and 11: Income statement. Column 10 includes all the income statement accounts with a debit balance, and Column 11 includes all the income statement accounts with a credit balance.

Columns 10 and 11: Income statement. Column 10 includes all the income statement accounts with a debit balance, and Column 11 includes all the income statement accounts with a credit balance.

When you’re confident that all the accounts are in balance, post your adjustments to the General Ledger so that all the balances in the General Ledger include the adjusting entries. With the adjustments, the General Ledger will match the financial statements you prepare.

Changing Your Chart of Accounts

After you finalize your General Ledger for the year, you may want to make changes to your Chart of Accounts, which lists all the accounts in your accounting system. (For the full story on the Chart of Accounts, see Chapter 3.) You may need to add accounts if you think you need additional ones or delete accounts if you think you’ll no longer need them.

You can add accounts to your Chart of Accounts throughout the year, but if you decide to add an account in the middle of the year in order to more closely track certain assets, liabilities, revenues, or expenses, you may need to adjust some related entries.

Suppose you start the year out tracking paper expenses in the Office Supplies Expenses account, but paper usage and its expense keeps increasing, so you decide to track the expense in a separate account beginning in July.

First, you add the new account, Paper Expenses, to your Chart of Accounts. Then you prepare an adjusting entry to move all the paper expenses that were recorded in the Office Supplies Expenses account to the Paper Expenses account. In the interest of space and to avoid boring you, the adjusting entry I give here is an abbreviated one. In your actual entry, you’d probably detail the specific dates paper was bought as an office supplies expense rather than just tally one summary total.

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Paper Expenses |

$1,000 |

|

|

Office Supplies Expenses |

$1,000 |

|

|

To move expenses for paper from the Office Supplies Expenses account to the Paper Expenses account. |

||

Answers to Problems on Adjusting the Books

1 Your annual depreciation expense is $6,000: $30,000 ÷ 5 = $6,000. Here’s what the entry looks like:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Depreciation expense |

$6,000 |

|

|

Accumulated depreciation — Office Machines |

$6,000 |

2 Your annual depreciation expense is $6,410: ($300,000 – $50,000) ÷ 39 = $6,410. Here’s what the entry looks like:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Depreciation expense |

$6,410 |

|

|

Accumulated depreciation — Buildings |

$6,410 |

3 Your annual depreciation expense is $21,429: ($200,000 – $50,000) ÷ 7 = $21,429. Here’s what the entry looks like:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Depreciation expense |

$21,429 |

|

|

Accumulated depreciation — Buildings |

$21,429 |

4 Your monthly insurance expense is $1,750: $10,500 ÷ 6 = $1,750. (Because you pay insurance semiannually, each payment includes six months.) Here’s what the entry looks like:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Insurance expenses |

$1,750 |

|

|

Prepaid expenses |

$1,750 |

5 Your monthly rent expense is $4,000: $12,000 ÷ 3 = $4,000. Here’s what the entry looks like:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Rent Expenses |

$4,000 |

|

|

Prepaid Expenses |

$4,000 |

6 You ended the month with $1,000 more inventory than you started the month with, so you need to increase the inventory on hand by $1,000 and decrease the Purchases expense by $1,000 because some of the inventory purchased will not be used until the next month. The entry is as follows:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Inventory |

$1,000 |

|

|

Purchases |

$1,000 |

7 Your adjusting entry looks like this:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Inventory |

$250 |

|

|

Purchases |

$250 |

This entry decreases the amount of the Purchases expenses because you purchased some of the inventory that wasn’t used.

8 Your adjusting entry looks like this:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Bad Debt Expense |

$2,000 |

|

|

Accounts Receivable |

$2,000 |

9 First, you need to calculate the amount of the bad debt expense:

Bad debt expense = $10,000 × .05 = $500

Your adjusting entry looks like this:

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Bad debt expense |

$500 |

|

|

Accounts receivable |

$500 |

10 Your initial entry is

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Payroll Expenses |

$10,000 |

|

|

Accrued Payroll Expenses |

$10,000 |

Your entry when you actually pay out the cash is

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Payroll Expenses |

$10,000 |

|

|

Accrued Payroll Expenses |

$10,000 |

|

|

Cash |

$20,000 |

11 First, you need to calculate the per-day payroll amount:

$5,000 ÷ 10 = $500 per day

Four days of payroll = $2,000 for May payroll expense

Six days of payroll = $3,000 for June payroll expense

Your initial entry is

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Payroll Expenses |

$2,000 |

|

|

Accrued Payroll Expenses |

$2,000 |

Your entry when you actually pay out the cash is

|

Debit |

Credit |

|

|

Payroll Expenses |

$3,000 |

|

|

Accrued Payroll Expenses |

$2,000 |

|

|

Cash |

$5,000 |

You can speed up depreciation if you believe that the asset will not be used evenly over its lifespan — namely, that the asset will be used more heavily in the early years of ownership. I talk more about alternative depreciation methods in Chapter 12.

You can speed up depreciation if you believe that the asset will not be used evenly over its lifespan — namely, that the asset will be used more heavily in the early years of ownership. I talk more about alternative depreciation methods in Chapter 12.