18

“THE ROAD NOT TAKEN”

After all, if all the experts insist that experts have value, who are non-experts to disagree?

NOAH SMITH

These are times of madness dressed in good suits.

PAUL KRUGMAN

Reason, unable to cope with genius, has wed itself to mediocrity.

JOHN RALSTON SAUL

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference

ROBERT FROST

You should understand, and probably do if you have read this far, that I am a barbarian. As I mentioned at the beginning of this book, I am not going to lay out the problems that lie before us and then call for legislation, or more money, or signing petitions, or ask you to recycle. I am going to make another suggestion. And it is a suggestion that will contradict everything you have been taught, everything that you have come to believe about yourself and our Western culture. It will undoubtedly be upsetting, seem crazy even. I am about to suggest that you to give up trust in experts and to begin to trust yourself . . .

It doesn’t sound too upsetting yet, does it?

(Don’t worry, it will.)

We exist in a time where nearly all of us in the West have been trained to put our trust in experts, most especially in the terminally schooled. In fact, most people who examine their lives in any depth will often find that from the moment they began formal schooling they were trained in a deep mistrust of their own perceptual capacities, of their own genius, of their capacity to feel, of their own ability to find solutions to the problems that face them, and our species. At the same time they often find they have been trained to believe that some undefined expert—someone out there—is better able to find solutions, possesses more genius, has more knowledge, and is in general more competent and thus more worthy of trust. And to them they have been trained to turn—and this is true even if they spend much of their life attaining advanced degrees themselves.

So, we reach a bifurcation in this book, a divergence of paths. One path is composed of the belief that the incredible edifice of Western schooling and reductive science and experts—a top-down control over all things—is the way we must approach the problems that face us. Or as Ken Wilber once put it . . .

It is science and only science

that can solve the problems facing us

I mean, it’s the adult thing to do. Or as Mary Midgley describes it . . .

The notion of “primitive animism” comes from a familiar Enlightenment myth which compares the intellectual development of the human race to that of an individual. That myth gave the name “animism” to a supposedly childish “primitive” phase, followed, first by more organized religions, then by metaphysics, and finally, in the adult state, by science, which made all its forebears obsolete. Smaller, more “primitive” cultures were always more childish than larger ones, and non-Western cultures, similarly, were more childish than that of the West. Finally, all other Westerners were more childish than Western scientists, who emerged as the only truly adult members of the species.1

The alternate path I am suggesting is very different. It is composed of a deep belief and trust in the individual, a belief that all solutions must occur on the ground in the location where the problems are most manifest, that those solutions must be created by those who live in those locations, generated out of their own inherent genius and their own deeply human nature, which, of course, includes things like empathy, love, adaptability, intuition, spirituality, and their own unique form of reason.

I take the second road . . . and this book is an expression of that road, of the more than forty years that I have spent upon it, and of what I have found there. It is the road I am suggesting you explore for yourself.

Besides a barbarian, I am, in many respects, a child of the late- nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, and my values have been shaped by those times. The United States in 1952 was a very different place than it is now and the threads of the old republic, and its values, were still vibrant then. Trust in the individual was still strong and the technocrats had not yet taken control. Vestiges of the great experiment of the American republic still remained. And that experiment? It will make you uncomfortable to hear it . . .

I can hear the objections now

The great experiment of the New World was that any person could engage in any profession at any time irrespective of prior training. There were no licensure boards, no laws prohibiting entry into any profession, no decades of schooling necessary to do work of any kind. And the structure of the government that was created at that time was intended to preserve that freedom of the individual.

I told you this would be upsetting

It was a complex and extremely brilliant creation;

and yes, there were

problems . . .

but I am not talking about those now

it was built around trust in the inherent genius of individuals and a strong distrust of bureaucratic institutions and elites. The tremendous innovation that occurred in the century and a half after the republic’s formation are a testament to its soundness.

In the years since I was born—and in my studies of the five decades preceding my birth—I have seen the degree of innovation that occurs in any area that is unregulated by government, schooling, and licensure. It is significant.

The innovations in physics, electricity, automobiles, and communication that occurred in the early part of the twentieth century were, for the most part, developed by the self- or (compared with our time) minimally-taught. Since then innovations in music, healthcare (massage, oriental medicine, herbalism, psychotherapy, midwifery), genre literature, computer technology, and sustainable agriculture (permaculture), as examples, have all been driven primarily by the unschooled, the unlicensed, the eccentrics who live outside the center. Anna Freud commented succinctly on this phenomenon when she stated (in 1968) that

When we scrutinize the personalities who, by self-selection, became the first generation of psychoanalysts we are left with no doubt about their characteristics. They were the unconventional ones, the doubters, those who were dissatisfied with the limitations imposed on knowledge; also among them were the odd ones, the dreamers, and those who knew neurotic suffering from their own experience. This type of intake has altered decisively since psychoanalytic training has become institutionalised and appeals in this stricter form to a different type of personality. Moreover, self-selection has given way to the careful scrutiny of applicants, resulting in the exclusion of the mentally endangered, the eccentrics, the self-made, those with excessive flights of imagination, and favouring acceptance of the sober, well-prepared ones.2

“The sober, well-prepared ones.” It is important to understand that the sober, well-prepared ones are not equipped constitutionally to deal with nonlinearity. As Paul Krugman once put it, when talking about economic nonlinearity, “Experience has made it painfully clear that men in suits not only don’t have any monopoly on wisdom, they have very little wisdom to offer.”3 The writer Jenny Diski captures some of what is at the core of the sober ones when she says that

They were the ones who never thought to doubt that everything they knew and thought was right and good and normal, that whatever they did not know or had not heard of was subversive and dangerous, and who had moral rectitude stamped, like Blackpool rock, through their unbending spines from coccyx to brain stem. . . . There was the same quivering, tight-lipped prissiness, the untroubled moral righteousness, a desire for the respectable and normal so powerful [that it governed every movement of life].4

The writer and psychologist Adam Phillips reaches deeper into its absurdity when he reveals that

Psychoanalysts after Freud have to acknowledge that the founder of psychoanalysis was never properly trained . . . and there was no one to tell him whether what he was doing with his patients was appropriate. That Freud was the first “wild” analyst is one of the difficult facts in the history of psychoanalysis. It is easy to forget that in what is still its most creative period—roughly between 1893 and 1939—when Freud, Jung, Ferenczi, Klein and Anna Freud herself were learning what they thought of as the “new science,” they had no formal training. Later generations of analysts deal with their envy of Freud and his early followers by making their trainings increasingly rigorous, by demanding and fostering the kind of compliance— usually referred to as “conviction”—that tended to stifle originality. Psychoanalytic training became a symptom from which a lot of people never recovered.5

Please understand. Those original people, they self-selected. (Or as Einstein put it, “true art is characterized by an irresistible urge.”) That is what people do who follow a deep, inner sense that there is something they must do. It is the mark of those who follow their hearts, who follow their natural interests. There is something inside them calling them to a particular place, a particular kind of study, knowledge, and awareness. Those that follow that inner urging, who find and never let go of golden threads, are the ones who change everything.

And no, formalized schooling of the sort we have now can’t support such a thing. It is antithetical to its very nature.

Perhaps nothing captures this truth more powerfully than William Deresiewicz’s “The Disadvantages of an Elite Education.”

It didn’t dawn on me that there might be a few holes in my education until I was about 35. I’d just bought a house, the pipes needing fixing, and the plumber was standing in my kitchen. There he was . . . and I suddenly learned that I didn’t have the slightest idea what to say to someone like him. So alien was his experience to me, so unguessable his values, so mysterious his very language, that I couldn’t succeed in engaging him in a few minutes of small talk before he got down to work. Fourteen years of higher education and a handful of Ivy League degrees, and there I was stiff and stupid, struck dumb by my own dumbness. “Ivy retardation,” a friend of mine calls this. . . .

It’s not surprising that it took me so long to discover the extent of my miseducation, because the last thing an elite education will teach you is its own inadequacy. As two dozen years at Yale and Columbia have shown me, elite colleges relentlessly encourage their students to flatter themselves for being there, and for what being there can do for them. . . . To consider that while some opportunities are being created, others are being cancelled and that while some abilities are being developed, others are being crippled is, within this context, not only outrageous, but inconceivable. . . .

My education taught me to believe that people who didn’t go to an Ivy League or equivalent school weren’t worth talking to, regardless of their class. I was given the unmistakable message that such people were beneath me. . . . I never learned that there are smart people who don’t go to elite colleges. . . . I never learned that there are smart people who don’t go to college at all.6

Deresiewicz notes that his Ivy League students rarely take risks after graduation, for they have never learned to fail and, as he comments, risking always entails failures along the way. His students are in fact so inculcated in one particular view of reality that they can’t even see the risks that need taking, can’t even ask the big questions that a fully aware life demands be asked. As Deresiewicz says, “We are slouching, even at elite schools, toward a glorified form of vocational training.”

Indeed, that seems to be exactly what those schools want. There’s a reason elite schools speak of training leaders, not thinkers—holders of power, not its critics. An independent mind is independent of all allegiances, and elite schools, which get a large percentage of their budget from alumni giving, are strongly invested in fostering institutional loyalty. As another friend, a third-generation Yalie says, the purpose of Yale college is to manufacture Yale alumni. . . . [Yet] being an intellectual begins with thinking your way outside of your assumptions and the system that enforces them. But students who get into elite schools are precisely the ones who have best learned to work within the system, so it’s almost impossible for them to see outside it, to see that it’s even there. . . . The tyranny of the normal [is] very heavy in their lives.7

Still, he says, some students intentionally refrain from attending Ivy League schools, often because they have a more independent spirit, because they know they will not become educated there, only schooled.

They didn’t get straight A’s because they couldn’t be bothered to give everything in every class. They concentrated on the ones that meant the most to them or on a single strong extracurricular passion or on projects that had nothing to do with school or even with looking good on a college application. . . . [They were] more interested in the human spirit than in school spirit.8

And it is from this eccentricity, this self-selection, this individuality, this capacity for thinking outside the assumptions of the system that change comes, that the different kind of thinking we need arises.

James Lovelock himself noted in his autobiography that he could never have done what he did had he trained similarly to the way so many scientists are now forced to do. He had, when he began, the freedom to design his own degree, to study in multiple disciplines, to learn from people who had themselves trained similarly. He was not forced into a narrow specialty. He had the freedom to follow where his heart led him. And he stubbornly remained outside the mainstream, an independent scientist. Lovelock comments that

I have been an explorer looking for new worlds, not a harvester from safe and productive fields, and life at the frontier has shown me that there are no certainties and that dogma is usually wrong. I now recognize that with each discovery the extent of the unknown grows larger, not smaller. The discoveries I made came mostly from doubting conventional wisdom, and I would advise any young scientist looking for a new and fresh topic to research to seek the flaw in anything claimed by the orthodox to be certain.9

In virtually every field in which great innovation has occurred, the early explorers were either untrained, minimally trained, unconventionally trained or trained in some other, unrelated, field. And all of them found flaws in the assertions of the orthodox.

It is the origin of Lynn

Margulis’s work

She refused to believe her teachers when they told her

the nuclei in the mitochondria were irrelevant

The great herbal renaissance that began in the U.S. in the late 1960s and early 1970s was initiated by people who were not trained in any formal way. Anna Freud’s descriptions of the early psychoanalysts fits them perfectly—as it does the musicians of the 1960s and the computer geeks of the ’70s and ’80s.

And the permaculturists and the . . .

Thus we saw the greatest flowering of herbal knowledge and development in the Western world since the 1880s. Predictably, as the field grew, many of the early innovators began to seek licensure, to create organizations to govern practice, and to institute requirements for practice that they, themselves could never have met—and which many still cannot meet. They begin to seek the “sober, well-prepared ones.” To get around the new requirements, they simply voted themselves the credentialing—after all it was their organization. (The same thing happened in psychoanalysis.) Few of them seem to see the contradiction in this, in the fact that it was the very lack of reductionist schooling and preset areas of study that allowed them to engage in so much innovation. They followed where their interests led them, where the Earth and their own hearts called them. And in so doing their inherent genius found what it was here to do, what it was here to say.

Some of them have told me that it was okay for them to do this, but that people now are too stupid to be allowed to. Because, you know, it was different then.

And yeah, they really said it . . .

But it is something I cannot accept

I cannot accept that you, who are reading this, are too stupid

to follow your own hearts, and in the process,

bring the solutions we need into the world.

As the early pioneers’ gating channels narrow with age, as they actively seek to protect their lawns, as the more eccentric die off, more regulation occurs and innovation begins to grind to a halt. A conservative mind-set takes over; the field begins to experience a distortion of its original purpose. It becomes a battleground for the accumulation of money and power. In the latter part of the eighteenth century this exact problem was common in Europe, so here, as those in the colonies struggled to craft a new country . . . they did something different. They trusted the individual. Anyone was free to engage in any profession they wished. There was no licensure, no legal regulation, no top-down control.

But what about protecting the public?

What about safety?

The objections that are emerging in your mind to that statement are an indication of the depth of lack of trust in the individual in which you have been trained. It is, as well, an indication of the degree to which you have been trained to believe that experts can solve the problems facing us. And as well to believe that such training, such expertise, such licensure produces greater safety for the public. It doesn’t.

What is really true

is that such processes can’t protect the public

in reality, they can’t

Analyses of licensure laws continually show that they do not produce more safety to the consumer. More deeply however, it is important to look at what that kind of orientation regarding the professions does in the real world. It, by its nature, prevents the discovery and creation of things like psychoanalysis. And just as with nonlinearity in living systems, there is a growing recognition in a number of quarters of this exact problem. Social scientist Nigel Clark comments that

When confronted by claims of the self-enclosure of any political or social entity, we have learned to ask what is being excluded or marginalized by the act of demarcation: what is being disavowed on the inside and what is being banished to the outside.10

In this instance, it is human ingenuity and genius and the capacity for analogical thinking—for individual eccentricity—that is banished to the outside. The loss to the human community is considerable. As the writer and editor Jon Graham put it, “analogy can connect the body and mind, objective space and subjective space, and the animal plant and mineral realms in ways that logic cannot. It is the key to the groundbreaking correlations [Annie] Le Brun makes between the environmental degradation of our physical world and the ravages suffered by the imaginal realm of our minds. The relationship between the disappearance of the great mammals like the blue whale and the great rebels of times past is the same.”11

There is an assumption that this banishment, this adoption of the sober, serious ones and their system of control, can produce safety. But part of what is left out of the top-down control mind-set is that all such systems are run by people, are composed of people, and all of them possess the same flaws that all people do, including the lust for power, prestige, and money.

Years of training, licensure boards, continuing education credits, and training based on reductive science do not in fact produce better or safer outcomes. And they never have. An analysis of outcomes shows it and the awareness of the flaws in the system in which we have been trained is becoming apparent to many. The primary outcomes in such systems are a significant increase in costs to the public and an incredible decrease in innovation . . . and, ultimately, as resistant bacteria show, great harm to the public.

This is why the health care system in the United States is the most expensive on Earth . . . and why its outcomes are so poor.

John Ioannidis of the Institute for Clinical Research and Health Policy Studies, Department of Medicine, at Tufts University published a rather remarkable article in August 2005; the title is interesting: “Why Most Published Research Findings are False.” He comments that

Published research findings are sometimes refuted by subsequent evidence, with ensuing confusion and disappointment. Refutation and controversy is seen across the range of research designs from clinical trials and traditional epistemological studies to the most modern molecular research. There is increasing concern that in modern research, false findings may be the majority or even the vast majority of published research claims. However, this should not be surprising. It can be proven that most published research claims are false.12

“Most published research claims are false.” Ioannidis found that underneath the practice of science in the Western world lay not a solid foundation but a sandy beach. He noted that his research, focusing primarily on medicine, found in nearly every instance that “the studies were biased. Sometimes they were overly biased. Sometimes it was difficult to see the bias, but it was there.” As David Freedman, in the Atlantic, reports . . .

Researchers headed into their studies wanting certain results—and lo, and behold, they were getting them. We think of the scientific process as being objective, rigorous, and even ruthless in separating out what is true from what we merely wish to be true, but in fact it’s easy to manipulate results, even unintentionally or unconsciously. “At every step in the process there is room to distort results, a way to make a stronger claim or to select what’s going to be concluded,” says Ioannidis. “There is an intellectual conflict of interest that pressures researchers to find whatever it is that is most likely to get them funded.”13

Even randomized, controlled trials were found to be heavily influenced by bias, to show what the researchers . . . and the funders . . . wanted them to show. Ioannides tested his findings by looking at forty-nine of the most highly regarded journal articles (and their research findings) in medicine in the previous thirteen years. These were the studies felt to be the most impeccable, best designed, and possessing the least chance of bias. He found that up to half of them were wrong or substantially exaggerated. Going further afield, Ioannides found that studies showing links between genetic structure and diseases, links that then led to specific treatments for anything from “colon cancer to schizophrenia have in the past proved so vulnerable to error and distortion that in some cases you’d have done about as well by throwing darts at a chart of the genome.” He notes that “even when the evidence shows that a particular research idea is wrong, if you have thousands of scientists who have invested their careers in it, they’ll continue to publish papers on it. It’s like an epidemic, in the sense that they’re infected with these wrong ideas, and they’re spreading it to other researchers through journals.”14 An editorial in the prestigious journal Nature went so far as to say, “Scientists understand that peer review per se provides only a minimal assurance of quality, and that the public perception of peer review as a stamp of authentication is far from the truth.”15

Ironically, considering the Nature editor’s comments, Nobel Prize– winner Randy Schekman recently added his voice to the chorus with his article “How journals like Nature, Cell, and Science are damaging science: The incentives offered by top journals distort science, just as big bonuses distort banking.” And those incentives? They are part of a growing problem; the journals are no longer forums for the publication of disinterested science but have become instead resources for the corporate accumulation of money and power. This is because, over the past several decades, most of the important journals have been acquired by large corporations who are now using that control to financially leverage their niche.

These corporations, unsurprisingly, are often found to have close ties to other corporate entities whose interests are affected by the research the journals print. It is no wonder then that as consolidation has progressed, the journals have begun to control what is allowed to appear in print as well as who can access it. They are, in essence, controlling what kind of research is done and the outcomes the papers report. This distorts not only research but the knowledge base science is presumed to rest upon.

As a brief look at the publishing giant Reed Elsevier shows, the income stream generated from this kind of journal control is massive.

Formed by the merger of Reed Publishing and Elsevier Scientific in 1993, Reed Elsevier is one of the largest publishers of science journals and academic texts in the world. In 2001 the company bought Harcourt Press (which already owned Academic Press). Numerous journals are published under these four imprints, giving Elsevier massive influence across a wide range of scientific disciplines. As consolidation like this has occurred, companies such as Elsevier have begun to significantly increase fees to universities and libraries for subscriptions. A single journal, which once cost as little as $200 per year, is now costing as much as $20,000. (This has caused many universities, such as the University of California, to stop subscribing.) The combined Reed Elsevier corporation, much of whose business occurs through online research, dwarfs other online juggernauts such as eBay and Amazon. Its annual revenues? Eight billion dollars, eight times eBay and over twice that of Amazon.

The company, as John Carlos Baez, a mathematical physicist at the University of California, notes, has engaged in numerous practices (besides price and market control) that raise serious concern. Two are, as he observes, “Elsevier’s recent support of the Research Works Act, which would try to roll back the U.S. government’s requirement that taxpayer-funded medical research be made freely available online. The six fake medical journals Elsevier created, which had articles that looked like peer-reviewed research, were actually advertisements paid for by the drug company Merck.”16

In the first decade of the twenty-first century, in response to these kinds of problems, some thirty thousand scientists signed a pledge to only publish in, edit, review for, or subscribe to scholarly and scientific journals that agreed to unrestricted free distribution (open access). Unsurprisingly, for-profit publishers were not supportive. In consequence, academics and researchers throughout the world began to create freely available alternative publishing venues such as the Public Library of Science (PLoS).

Despite this, and whether or not corporate control of research and prestigious journals is inhibited, the problems inherent in disciplines run by human beings are unlikely to be eliminated (though, with focus, they can, to some extent, be minimized). As Paul Krugman has observed . . .

Many people seem to have a much-idealized vision of the academic process, in which wise and careful referees peer-review papers to make sure they are rock-solid before they go out. In reality, while many referees do their best, many others have pet peeves and ideological biases that at best greatly delay the publication of important work and at worst make it almost impossible to publish in a refereed journal.17

Scientists and researchers, nearly everyone forgets, are people, and they suffer the same limitations and problems all people do, irrespective of Ph.D. status. Greed is just one of them. Historian Steven Shapin, in his massive work Never Pure, has carefully tracked how science is, and always has been, an expression of unexamined cultural structures, relations, beliefs, and survival needs. It is shaped most commonly by the beliefs and attitudes of the culturally and socially powerful to mirror and spread those beliefs. As he relates . . .

The historical case for the existence of knowledge without prejudice is not good. Knowledge free of prejudice has not been obtained in historical practice, and it is probably impossible to obtain in principle. The Republic of Science seems rather to reflect the most widely distributed prejudices of its time and of its citizens. And, insofar as these are so widely distributed, they may appear to its citizens as no prejudices at all.18

The same unexamined biases that encouraged scientists of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to find, for instance, that women, blacks, Jews, indigenous peoples (and dolphins, and plants and bacteria) were all inferior to Caucasian males; or to assert that the Earth is not alive; or that dissociated mentation is free of bias; or that linear reasoning is the way to true understanding of Universe are, and always will be, in play. It is not a patriarchal thing; it is a human thing. In consequence, science is not, never has been, and never can be value free. The truth is, science isn’t all that different from anything else that humans do. It isn’t the way to unbiased truth. It can’t supply value-free, objective answers to the problems we face. It is not and never has been free of prejudicial presuppositions about the nature of the reality in which its practitioners are embedded. It is just a tool, and like all tools it has inherent limitations. It is useful for some things, not useful for others. Using it to solve our current problems is like using a hammer (if that’s the only tool you have) when what you need is a screwdriver.

We can’t solve problems

by using the same kind of thinking we used

when we created them.

Many supporters of science are uncomfortable with this kind of statement (especially from outsiders); they insist that the continual give and take that occurs in science ultimately reveals the errors that are present, that the strength of the field is that it corrects itself. In actuality, that is generally untrue.

In actuality, that is generally untrue.

Most of the refutations come from people outside the fold, the eccentrics who are following independent research interests and whose livelihood does not depend on funding. And even then, even though a wrong idea has been definitively proven to be inaccurate Ioannides found that it tended to persist as accepted truth for decades afterward. He has found that up to 90 percent of all medical research and subsequent practice is flawed, often seriously so. And this is not limited to medicine; other researchers have found similar outcomes in all fields of science, from physics to economics.

To paraphrase Paul Krugman (he was talking about economists), Western science has very much the psychology of a cult. Its devotees believe that they have access to a truth that generations of differently thinking humans have somehow failed to discern; they go wild at the suggestion that maybe they’re the ones who have an intellectual blind spot. And as with all cults, the failure of prophecy—in this case the various utopian materialist fantasies—only strengthens the determination of the faithful to uphold the truth.19

People have been trained to believe that “science” is a foundational approach that, by its very nature, leads to accurate pictures of the world around us and that basing action on those pictures will lead to a better world. But science is only a tool and like all tools is only as good as its user. And scientists, irrespective of their background, are still only people, with all the problems, and limitations, that all people have. They are not, by definition, better people or better thinkers than anyone else you might meet on a crowded street.

Part of the reason for our current troubles is because the practice of what is called science has changed considerably, and not for the better, since the late 1800s and early 1900s.

It’s now filled with the sober, well-prepared ones.

It was, once, the practice of what is more accurately natural philosophy. These were people, male and female, of all nationalities, degreed and nondegreed, who were interested in understanding the world in which they lived. They were the self-selected. As Michael Crichton comments . . .

For four hundred years since Galileo, science has always proceeded as a free and open inquiry into the workings of nature. Scientists have always ignored national boundaries, holding themselves above the transitory concerns of politics and even wars. Scientists have always rebelled against secrecy in research, and have even frowned on the idea of patenting their discoveries, seeing themselves as working to the benefit of all mankind. And for many generations, the discoveries of scientists did indeed have a peculiarly selfless quality.

But in the late 1970s this began to change. As Crichton continues . . .

Suddenly it

seemed as if everyone wanted to become rich. New companies were announced almost

weekly, and scientists flocked to exploit genetic research. By 1986, at least

362 scientists, including 64 in the National Academy, sat on the advisory boards

of biotech firms. The number of those who held equity positions or consultancies

was several times greater.

It is necessary to emphasize how significant this shift in

attitude actually was. In the past, pure scientists took a snobbish view of

business. They saw the pursuit of money as intellectually uninteresting, suited

only to shopkeepers. And to do research for others, even at the prestigious Bell

or IBM labs, was only for those who couldn’t get a university appointment. . . .

But that is no longer true. There are very few molecular biologists and very few

research institutions free of commercial affiliations. The old days are gone.

Genetic research continues, at a more furious pace than ever. But it is done in

secret, in haste, and for profit.20

And this is true not only in genetic research but in all fields of science, including, as examples, medicine, Earth system studies, and economics. In consequence, the entire practice of what we call science has been distorted considerably. What is studied, who is allowed to study it, the outcome of studies, what studies are made public, and how the accumulated knowledge is put into practice are all controlled by corporate interests—with the active participation of most researchers, and most universities. It doesn’t really matter whether the outcomes benefit society, only that they make a profit. Things have gotten so bad in medicine that it moved Marcia Angel, M.D., to write . . .

It is no longer possible to believe much of the clinical research that is published, or to rely on the judgement of trusted physicians or authoritative medical guidelines. I take no pleasure in this conclusion, which I reached slowly and reluctantly over my two decades as an editor of The New England Journal of Medicine.21

“It is no longer possible to believe much of the clinical research that is published . . . or to rely on the judgement of trusted physicians . . .” This is a very difficult statement to accept, and it applies to experts in nearly every field, including environmentalists, ecologists, and public safety advocates. Even such a prestigious environmental activist as David Suzuki has recognized the problem. “Environmentalism,” he says, “has failed.”22 And it has failed for the same reasons that science is failing: reliance on dissociative mentation, uncorrected human limitations, unrestrained power and money, and top-down approaches.

I still remember the great public movement urging people (and businesses) to switch to plastic bags and abandon paper—a movement begun by “expert” environmental activists. And I remember their triumph—and that of the public—when paper was abandoned on the West coast. And I notice now, decades later, when plastic waste has become such a problem, that calls are emerging for banning plastic and going to paper.

And those reusable shopping bags? Turns out they are the perfect breeding ground for noroviruses. In fact, that is one of the major ways the virus now spreads among human communities. From the lettuce to the table to the intestine.

The problems, as Einstein put it so well, come, in significant part, from how we think. And though we like to believe that the approach we are trained in here in the West is the best, it, in actuality, skews how we see and experience the world and in consequence skews any solutions we create. Analysis of research papers in the brain sciences (neuroscientists) have found significant biases in the work, just as they have been found in other areas of science. A lot of that bias occurs in what is studied.

Some 96 percent of behavioral science experimental subjects are from Western industrialized cultures who represent only 12 percent of the world population; 68 percent are Americans. Seventy percent of all psychology papers are produced in the U.S. while almost all psychological research is performed on graduate students, a group that represents 0.2 percent of the world population. Researchers take their results to be representative of the human species, but the outcomes are not actually generalizable to other populations.

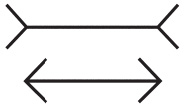

In fact, deep examination of the brain and psychological sciences has found that populations in the West, most especially in the United States, are abnormal when compared to the majority of humans on the planet. Most people just don’t think like we do . . . and they never have. As researchers Heinrich et al. put it, “The findings suggest that members of WEIRD societies [Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic], including young children, are among the least representative populations one could find for generalizing about humans.”23 When comparing visual perception, fairness, cooperation, spatial reasoning, categorization, inferential induction, moral reasoning, reasoning styles, self-concepts and related motivations, Westerners, most especially Americans, are not like anybody else. For instance, only Westerners fall for the Müller-Lyer optical illusion, which tricks the viewer into thinking one line is longer than another, when in fact both are the same length.

The Kalahari Bushmen, and all people in nonindustrial cultures, see the lines as the same length. We in the West fall for the illusion because we have spent our lives immersed in Euclidian landscapes. The sides of our buildings and corners of our ceilings give us familiarity with those types of lines. After a while we become lost in that framework. (And, interestingly, brain damaged people in the West can solve puzzles that the undamaged cannot. The disruption of linear reasoning forces the use of a different approach that, in itself, allows solutions to emerge.) Westerners, in fact, know very little about the mind of human beings but a lot about the mind of a very narrow subset of the human species, one that has spent its life immersed in an unnatural environment. Brain physiology in cultures other than the West is significantly different—as is how people think. The paradigm we are immersed in actually shapes physiology—what you are taught does in fact shape what you are able to perceive. And it alters brain structure accordingly.

It turns out that sensory gating is a lot more open in every other culture on Earth. The further away you get from industrialized reductionism, the more open they are. What those other cultures see is actually there. We in the West just can’t perceive it.

The primary activists (from scientists to environmentalists) for the planet are in Western industrial cultures, most especially in the United States. But they are in fact the least able to think differently, to actually abandon top-down approaches for the different kind of thinking Einstein urged us to find. The kind of thinking we are trained in here in the West just doesn’t work in the real world. And the kinds of top-down solutions that so many people want to impose on the rest of the world are, in nearly all instances, coming from a position of dissociation, that is, I am here, the world is over there.

The world is seen as a static backdrop and we humans are the only actors upon the stage. And this is fundamental to the Western paradigm—it’s inescapable. The solutions suggested are in nearly all instances static behaviors intended to be applied as a universal in all locations by all people. Such an approach will never work—though it is unlikely to stop people from trying it over and over again. The belief is that if we just keep doing the same thing but even more stringently it will eventually work. It won’t.

So, I am

suggesting you give up the approach

and do something different

The answers we need will never come from experts out there; they can’t. They will come from you—and people like you. Buckminster Fuller recognized this long ago, when he said . . .

- It is my driving conviction that all of humanity is in peril of extinction if each one of us does not dare, now and henceforth, always to tell only the truth, and all the truth, and to do so promptly—right now.

- I am convinced that humanity’s fitness for continuance in the cosmic scheme no longer depends on the validity of political, religious, economic, or social organizations, which altogether heretofore have been assumed to represent the many.

-

Because, contrary to that, I am convinced that human continuance now depends

entirely upon:

A. The intuitive wisdom of each and every individual.

B. The individual’s comprehensive informedness.

C. The individual’s integrity of speaking and acting only on the individual’s own within self-intuited and reasoned initiative.

D. The individual’s joining action with others, as motivated only by the individually conceived consequences of doing so.

E. The individual’s never joining action with others, as motivated only by crowd-engendered emotionalism, or by a sense of the crowd’s power to overwhelm, or in fear of holding to the course indicated by one’s own intellectual convictions.24

Bucky understood that the systems that are in place are creations of the old thinking, of the old paradigm. And he understood that such systems need to be abandoned, for they can never prepare us for the future that we now face, nor respond to the demands of our time. We need the eccentrics, the dreamers, the unconventional ones, the doubters, those who are dissatisfied with the limitations imposed on knowledge. They are the ones who can find solutions that the existing systems cannot.

In 2012, scientists who had been struggling for over a decade to find the molecular structure of an AIDS enzyme gave up. The methods they were using to find the structure, as they put it, “just didn’t work.” So, in desperation they turned the problem over to the internet and the gaming community. “To the astonishment of scientists,” as reporters put it, the problem was solved in ten days.25And in 2012 a 16-year-old solved a mathematical problem that had stumped mathematicians for 30 years. When the boy found out there was no solution he just refused, he said, to accept that it was so. So, he decided to “have a go” at solving it. He said the only reason he did so was “schoolboy naivety.”26

The Universe is a nonlinear, self-organized system. The Earth is a nonlinear self-organized system embedded within that larger system. Outcomes can’t be predicted by using a top-down approach. The analysis has to happen on the ground, in the moment, by people who are in relationship with and attending to that particular location. As Nigel Clark notes, “many of the ordering and controlling imperatives that were once definitive of modernity are now known to unleash cascades of unforeseen consequences: by-products that arise out of the sheer complexity attained in our interchanges with the biophysical world.”27

We are in the midst of a paradigm shift. One that is finally beginning to force us to abandon as foundational the Newtonian view of the universe as a place of predetermined, linear, cause-and-effect forces as well as the thermodynamic view that believed everything is sliding inexorably down into an inactive, featureless, equilibrium. As Clark comments, “the new view affords the cosmos an ongoing capacity to give rise to new structures, processes, and potentialities, a break with determinism that implies, as physicist Paul Davies points out, that the universe is intrinsically unpredictable . . . abrupt or discontinuous transformation is something we should expect.

“In the real world,” he observes, “there will always be some intrusion that ripples the surface of reasoned judgement . . . symmetry is broken and uniqueness asserts itself. . . . And it is that outside, leaking or bursting back in, that will sooner or later upset the dreams of a more evenhanded and regulated existence.”28 The “static” background acts, linear predictability fails, and as Jacques Derrida notes the still surface of the pond is shattered, “an irruption [takes place] that punctures the horizon, interrupting any performative organization, any convention, or any context that can be or could be dominated by a conventionality.”29 Conventional approaches, approaches based on a linear analysis of a (nonexistent) static background, will now, always fail.

It is the unruly masses that are most able to respond to such discontinuous transformations, that can engage with the unruly Earth and the unpredictablity of Universe. These are the ones who will “give rise to new structures, processes, and potentialities, [and] break with determinism.”

It is the eccentrics, the outsiders, those who have opened sensory gating channels and are willing to look deep into the scenario in which they are embedded who will find new structures and potentialities. That place of touching is where engagement with the world as it is will occur. That is where the old forms will be abandoned and new approaches found. It will not be in schools or in established degree programs. It will not be in government or in NGO hierarchies of “let-us-help-you- irrespective-of-what-you-think-you-need.” It will not be in old forms. It will come out of individual human beings and their love of place, their need, and their genius.

So . . . my suggestion is not for more studies, not for more government grants, not for trusting experts to solve the problems that face us. It is for you to follow your own genius, for you to find in yourself the still small spark of understanding that, with care, blossoms into genuinely new solutions to what you yourself see as problems. It is not about top-down solutions forced on the world’s populations by people whose desire more often than not is for control over others, but about each individual doing what he or she understands must be done by themselves in the location in which they themselves live.

This is in fact what Gaia does. Gaia generates organisms out of the ecological matrix of the planet to fulfill certain functions. And Gaia instills in each of those organisms a drive to fulfill that function. But how each organism responds, how each organism actually fulfills that function is up to them. They have the ability to choose. Gaia trusts the individual genius of each organism, to innovate, to respond, to create solutions to the individual events that each organism experiences. There is, in fact, no other way for the system to work, for homeodynamis to be retained, for the balance point to be maintained.

Bucky understood that only you know what it is that you should do in response to the challenges of our times. And he understood that Gaia speaks through the work that each of you is given, that deep inside you some part of you knows just what it is that you should be doing. And he understood that that thing in you, telling you what to do, is an expression of Gaia, speaking through the movements of your life. And that only if you trust that thing can the solutions to the challenges that face us be successfully met.

If we want to do something effective to address the problems that face us, then we must begin to use a different way of thinking than the thinking we used when the problems were created. That means we have to use a different kind of thinking. That means stepping outside the normal channels of thought, of questioning basic assumptions, of actually becoming different in the self. Ultimately, it means becoming barbarian.