— 6 —

THE MAGIC HOUR

Ssam in Korean means “wrapped.” There are endless variations, but if you’ve ever been to a Korean barbecue restaurant, you understand the basic concept: take a leaf of lettuce or perilla (a relative of shiso), fold it around some meat, vegetables, and maybe some rice, then top with ssamjang (literally “wrap sauce”). That’s the whole idea. Conceptually it’s almost identical to a tortilla filled with carnitas, beans, rice, and salsa.

Our opening menu at Ssäm Bar owed as much to Korean and Mexican tradition as it did to a late-night takeout habit I’d developed. Whenever I ordered Chinese food to my apartment, I’d be sure to get mushu pork, and then I’d use the pancakes to wrap everything—noodles, rice, stir-fries. Who doesn’t love wrapping food in other food?

The idea of authenticity comes up a lot in the culinary world, both as an ideal and as a criticism. In this conversation, there are usually more questions than answers. What makes something authentic? Is it always better to be authentic? Is authenticity the enemy of innovation? Honestly, having heard these questions asked ad nauseam, I’m bored by the whole topic. Not because it isn’t important. It is. But whenever someone starts talking about authenticity and cultural appropriation, my mind begins to wander. I ask myself, What if my ancestors had traded places and pantries with yours? What would modern Korean food look like if a generation of Changs and Kims and Parks had arrived in Mexico five hundred years ago? What would Mexican food look like? I imagine both cuisines would be even more delicious, and I bet they’d still be wrapping meat and vegetables in tortillas and leaves. We humans are more alike in our tastes than we think. Even with completely different tools and ingredients, we’re bound to arrive at the same conclusions.

I know this isn’t an airtight idea, politically speaking. It can be taken as license to do whatever you want without consideration for the source material. But as an Asian chef, I tend to get away with posing such scenarios more than I would if I were a white guy explaining why his Nashville hot chicken doughnut is actually an homage to black cooks. Yellow privilege, baby! It’s one of the few perks of being Asian that makes up for, you know, your skin color being referred to as “yellow.”

Anyway, as a creative engine in the kitchen, it’s a powerful thought exercise.*1

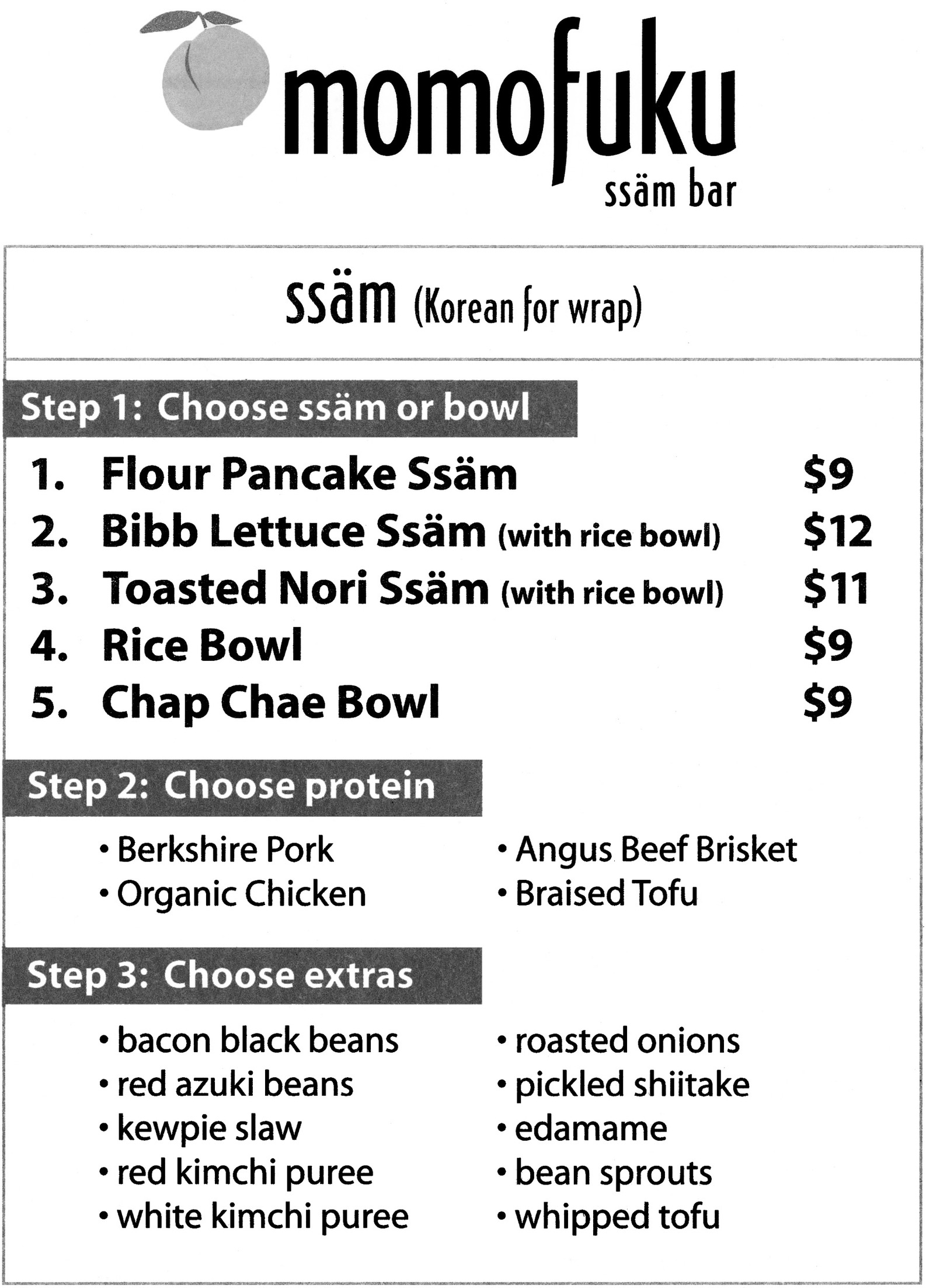

At Ssäm, we would have the same setup as Chipotle. The diners would see all their options arranged in front of them and customize their meal as they made their way from one end of the line to the cash register. They’d be served by legitimate chefs, sit in a decently appointed dining room, and listen to good music while enjoying affordable and carefully prepared food before heading back to work.

How could we lose?

We were a flop. People were not ready to follow us on our foray into fast food. Diners, it seemed, still wanted dining to feel special. I couldn’t convince them that this wasn’t just a cynical cash grab, or that we were trying to make food better at all levels.

Sometimes we would have colossal lines out the door, but far more days were spent scrubbing down the kitchen one extra time just to have something to do. For all practical purposes, we were dead. Forget about feeding the masses; we could barely count on Noodle Bar regulars to drop by once a week.

Thankfully, no major critics came. Why would they have bothered? We’d probably be out of business before their reviews came out.

“Just wait and hopefully people will come around” was my uninspiring take on Kevin Costner’s mantra in Field of Dreams.

As confusing as Ssäm Bar was to patrons, it was equally dispiriting for my chefs. Thanks to the storm of press for Noodle Bar, more reputable cooks had joined us. They had shown up to grind it out and cook exciting food but ended up intermittently scooping carnitas.

I’d promised them that entering the Momofuku universe meant no systems or hierarchies. They could cut the line, just as I had. I used to tell them, “We don’t have titles, because if you don’t know what you’re supposed to be doing, you don’t belong here.” It’s the sort of off-brand Confucian saying that covered up my own lack of clarity. I do believe that putting too much stock in titles and org charts can stifle a company. At the same time, not everyone thrives in an environment without structure or direction or a clear chain of command.

The cooks at Ssäm didn’t have enough to do, and there wasn’t room at Noodle Bar to accommodate any more bodies. Chief among the underutilized at Ssäm was Tien Ho, whom I’d met at Café Boulud. He could cook circles around me but still agreed to join as Ssäm’s opening chef. Momofuku attracted a certain type of person who considered themselves underdogs in some respect—the kind of people who got off on hearing their colleagues tell them it was career suicide to throw their lot in with ours. That was Tien, for sure. It was also a fitting description for Cory Lane, who, contrary to my earlier decree about not issuing titles, was the first person to ever hold the position of “manager” at Momofuku. Every fast-food place needs a manager, right?

Tien, Peter Serpico, Tim Maslow—these guys were the real deal. I’d prepared them to be busy. I bought two Alto-Shaams—the kind of combination steam oven that cruise ships purchase to feed thousands of people a night.

In my head, there was a clear road map to success: build a fast-food restaurant that serves high-quality food, and people will notice. They’ll line up for it across the country. Give it some time and they won’t even be able to see the seams between cultures in a Korean burrito. It will seem as natural as a hamburger.

But the proof was in the flour pancakes that sat on a shelf growing stale. It was evident in the bored looks on everyone’s faces. Thankfully, the crew was detached from the emotion I felt for my fast-food idea. With nothing to lose and nothing better to do, they woke me up to the truth. We had skill and a nice, big space. We were doing nothing meaningful with any of it. By not admitting defeat and changing course, I was wasting everyone’s time and putting both restaurants in danger. My accountant told me we had sixty days of capital left.

So we started cooking again and we fixed it. I eventually paid my dad back to become fully independent, and Ssäm Bar became solvent. It’s as simple as that. I know this is a cop-out, but the Ssäm Bar turnaround story sounds more or less identical to the narrative you already read about Noodle Bar. The long and short of it is that we began serving a late-night menu of dishes we knew chefs would want to eat after work.

Roll your eyes all you want. God knows it sounds clichéd. But at that time most chefs in America were giving their customers different food than they were eating themselves. What we ate after service was uglier, spicier, louder. Stuff you want to devour as you pound beer and wine with your friends. It was the off bits that nobody else wanted and the little secret pieces you saved for yourself as a reward for slogging it out in a sweaty kitchen for sixteen hours. It’s the stuff we didn’t trust the dining public to order or understand: a crispy fritter made from pig’s head, garnished with pickled cherries; thin slices of country ham*2 with a coffee-infused mayo inspired by Southern redeye gravy. My favorite breakthrough never made the cookbook: whipped tofu with tapioca folded in, topped with a fat pile of uni. So fresh, so cold, so clean, and so far outside of our comfort zone. There were so many ideas on the menu that we’d never seen or tried before. The only unifying thread was that we were nervous about every single dish we served.

Like I said, it was essentially the same philosophy that had saved us at Noodle Bar, but with an added layer of thoughtfulness and refinement. The important thing to take away is this: no idea was so bad that we shouldn’t try it. If someone on the team was passionate about something, we were all ears. We had to be.

We started charging for bread and butter, because we were serving better bread and butter than you were getting elsewhere. It was a decision that was not only antithetical to common restaurant sense, it’s actually illegal in parts of France.

Another seemingly dumb idea we embraced was not making enough food for everyone. The seeds for this notion were planted back when I was working for Jonathan Benno at Craft. I was responsible for making the uber-amuse for VIPs—a flight of oysters and other raw seafood with all the accoutrements, served in giant ice-filled copper pots. Whenever I was called upon to construct one of these, it worried me to no end, because as soon as this plateau of seafood went parading through the dining room, every head in the restaurant would turn. I knew I’d have to make ten more.

It’s the velvet-rope effect. If something seems exclusive, nobody wants to feel excluded. We tried to tap into that emotion at Ssäm Bar. While our namesake burritos eventually disappeared from the menu, the pork shoulder we filled them with was too delicious to let go. In its new incarnation, we chose to serve it whole rather than shredding it, with all the fixings needed to make little handheld wraps: rice, lettuce, kimchi, sauces, and fresh oysters. It was our spin on a Korean bo ssam. At first, we just gave it away to friends. Right in the thick of the dinner rush, we’d drop this monstrosity on a table in the middle of the dining room.

Just like that, we started hearing the exact question I was hoping for: How do I get that?

“Oh, by reservation, and it’s only available at five-thirty or ten-thirty.”

And that’s how we filled our restaurant during off-peak hours.*3

None of this is what I had in mind for Ssäm Bar, but I won’t complain about the steady, enthusiastic business that followed. I rolled with it, although, as always, I was constantly vacillating between extreme confidence and paralyzing self-doubt. I was comforted by the revelation that coming up against failure head-on is a powerful motivating tool. It means you’ve already stared the worst-case scenario in the face. It also means that you have more data than everyone else, freeing you up to take risks others won’t. By confronting failure, you take fear out of the equation. You stop shying away from ideas just because they seem like they may not work. You start asking whether an idea is “bad” because it’s actually bad or because the common wisdom says so. You begin to thrive when you’re not supposed to. You just have to be comfortable with instability, change, and a great deal of stress.

Here’s how I describe it to my cooks: we can spend twenty-three hours of the day wringing our hands, talking about possible new recipes. In that span of time, we will be able to make enough unwise and arbitrary decisions to jeopardize our motivation to take another stab at it in the morning. But in the moment of greatest need, in that final hour, we will see what needs to happen and put it into motion immediately.

I don’t mean this as a metaphor. I’ve found that the best moment to start working on a new dish is the hour before doors open, when everyone on staff is rushing to shovel food into their mouths and finish their mise en place; every kind of distraction is sure to present itself. On paper, it’s the worst possible time to try to be creative, but for that exact reason you end up with no choice but to make decisions and stick to them. You print the dish description on the menu and then you make it work. You can refine it later, but the only way to shut out all the unnecessary doubts in your head is to impose a deadline, and five-thirty p.m. is as good a time as any.

I thought I had unlocked the big secret, and now I wanted to bottle it. There were new voices in our organization and much more noise from the outside to tune out. We needed to record and examine what worked for us. At least that’s how I would put it now. This is how I explained it to the staff in May 2007:

The Roundtable, as the email list came to be known, grew to include as many as ten participants and encompass all kinds of discussions. On top of sharing sales numbers and information on ingredients, we’d give play-by-plays of memorable meals we’d eaten around town or talk about cooks whom we might want to bring into the fold. Mentions of hangovers were frequent. Quino and I made an effort to be as open as possible about any opportunities we were feeling out. I could throw my craziest ideas out there and put them to a vote. For instance:

This digital brain trust was nothing like the top-down systems you’d see at most places, where the leader usually keeps only a few trusted operatives aware of what’s truly going on. The emails allowed us to pause at the end of a crazy night and reset for the following day, equipped with new goals. The ceaseless chain of messages—if you slept in, you’d have to go through at least fifty replies—exemplified the aforementioned philosophy that there’s no idea we won’t consider. Everything is a data point we can use. TMI for most people is never enough for me.*4

The staff were giving everything they had to being better, to making Momofuku better. I felt an obligation to them. I devised what I hoped would be an alternative to the brigade system, a setup devoid of bullshit and hazing, with clear lines of communication that would allow us to grow without too much pain. I proposed breaking the company into subgroups—seven teams of about four people—each consisting of a leader, a veteran, a rookie, and a prep cook:

Momofuku turned into something between a committee and a commune. The Roundtable was an assembly of yellers and poor spellers—my frequent mistake was referring to green beans as “haircoverts”—where everyone’s opinion was not simply welcomed but mandatory. I may have been the most prolific contributor, because I valued the feedback so much.

I wish I could remember half of the inside jokes from these emails. Nevertheless, it brings me joy to reread them. Pemoulie:

No one knew when work ended or began. We were part of something we couldn’t appreciate until much later. Together, we were building a world, and while that task could be overwhelming, I realize now what a privilege it was to be able to focus all of our attention on it. The older I get, the more distractions get in the way—the more I’m drawn from the stove and the thing I’m best at. To this day, whenever I get together with Quino to catch up over dinner or a beer, we always say that the beginning of Momofuku was the best time of our lives. Nostalgia is funny that way. I don’t want to put words in everyone else’s mouths, but I hope they all look back on this period as fondly as I do.

We were winging it. We had thrown out our original plans for Ssäm in January and received validation of the course correction from The New York Times with a two-star review less than two months later. (The following year, the same critic, Frank Bruni, upgraded Ssäm to three stars, putting it on par with restaurants like Gramercy Tavern and…Café Boulud.) That first review saved the business and launched us into the stratosphere. I woke up one morning in March to learn that we had been nominated for two James Beard Awards: Rising Star Chef (me, for the second time) and Best New Restaurant (Ssäm).

For all my bluster, I was scared shitless. Writing about the facts of my life here, it seems like a logical progression. This happened and then that happened and I slowly learned this and by the time this moment came I was ready. But in between every triumph or epiphany I’ve described in this book, there were five hundred moments of doubt. There were embarrassments and mistakes, people I pissed off or disappointed, chances I squandered. There were dishes that sucked and services that made me want to tear my eyeballs out. And there was the constant thrum of depression in the back of my skull.

The accolades felt like they were coming out of nowhere. I’ve always had a knack for getting the best out of others, but it took me years to appreciate that as a skill. In the moment, it seemed as though I was sucking up all the credit for what was a team effort. When Dana Cowin called to inform me that I was one of Food & Wine’s Best New Chefs, I tried my best to decline. Ask her, if you don’t believe me. I kept waiting for someone to flip a switch in my brain that would make me think, You deserve this, Dave. You’re one of the best. Forget everything else. But it never came.

If there was one moment that was supposed to do it, it was the Beards. Being nominated for a Beard Award was the signal that I’d arrived, but it only generated more anxiety. I felt like I was hiding a shameful secret—that I didn’t deserve to be in the same company as my mentors, some of whom had been passed over for years by the Beards. The only coping strategy in my repertoire was to laugh it off. Or, as I suggested to the team, we’d just get too drunk to worry about winning or losing. They seemed on board.

Over the past thirty years, there has been no more important event for American restaurants than the James Beard Awards. For a massive industry that isn’t synonymous with high fashion or red carpets or classy behavior, the annual ceremony is a nice opportunity to play dress-up and be taken seriously. It’s black tie and, for a long time, was held in New York at the Marriott Marquis and later Avery Fisher Hall, where the Philharmonic plays. It is an aspirational and intensely ceremonial event, and with good reason: a Beard Award is the highest honor you can receive as a chef or restaurateur; joining the class of winners or even nominees can change a career.

People take it very seriously. I respected the awards deeply, I just didn’t respect myself, which made it all the more difficult to picture myself in a tux, strutting past those pretty fountains in Lincoln Center Plaza and into the room where Simon and Garfunkel, Miles Davis, and Leonard Bernstein had performed—not to mention thousands of extremely talented classical musicians. I wasn’t especially looking forward to chitchatting with all my highly respected peers from around the country. Everybody goes to the Beards.

But bailing would have been worse, so I channeled my anxiety into planning a night the team wouldn’t soon forget. Most people who come to town for the Beards try to hit the restaurants of the moment or pay their respects to established local chefs. It’s one of the coolest parts of the tradition. There are also a bunch of pre- and afterparties, hosted by restaurant groups and liquor companies and magazines. Our goal would be to minimize our exposure to small talk. It would be a set of activities designed to shield us from the gravity of the situation.

I secured a party bus, complete with disco lights, a smoke machine, and very shoddy leather seating. It was also outfitted with a stripper pole, which was a complete surprise to me. It was probably the first time the vehicle had been used to transport anybody other than horny bachelors. It also happened to be cheaper than any other available limo. I’d never gone to prom, but I imagined this wasn’t far off.

That evening in May, the whole gang and a few plus-ones got dressed to the nines and boarded the Momobus, which was pointed due northwest. I’d rented out Daisy May’s, Adam Perry Lang’s fine spot for smoked meat in Hell’s Kitchen. We were going to have some barbecue. When we arrived, we put on plastic aprons and rubber gloves, and wrapped our forearms with garbage bags to avoid getting our clothes dirty. We drank beer and liquor from red Solo cups. We served ourselves from aluminum platters filled with pulled pork, ribs, Texas toast, and coleslaw.

Our good mood lasted us through the event, which went by in a blur. Ssäm didn’t get the award, but I did, which made me want to blow things out even more ridiculously during the ride around town later that night. The pictures from the rest of the evening suggest we did a pretty good job of that.

I got some feedback in the aftermath that gave me the impression that other attendees found our behavior to be disrespectful. That’s a fair way of seeing it. But the truth is, it was one of the nicest things we’d ever done together as a family.