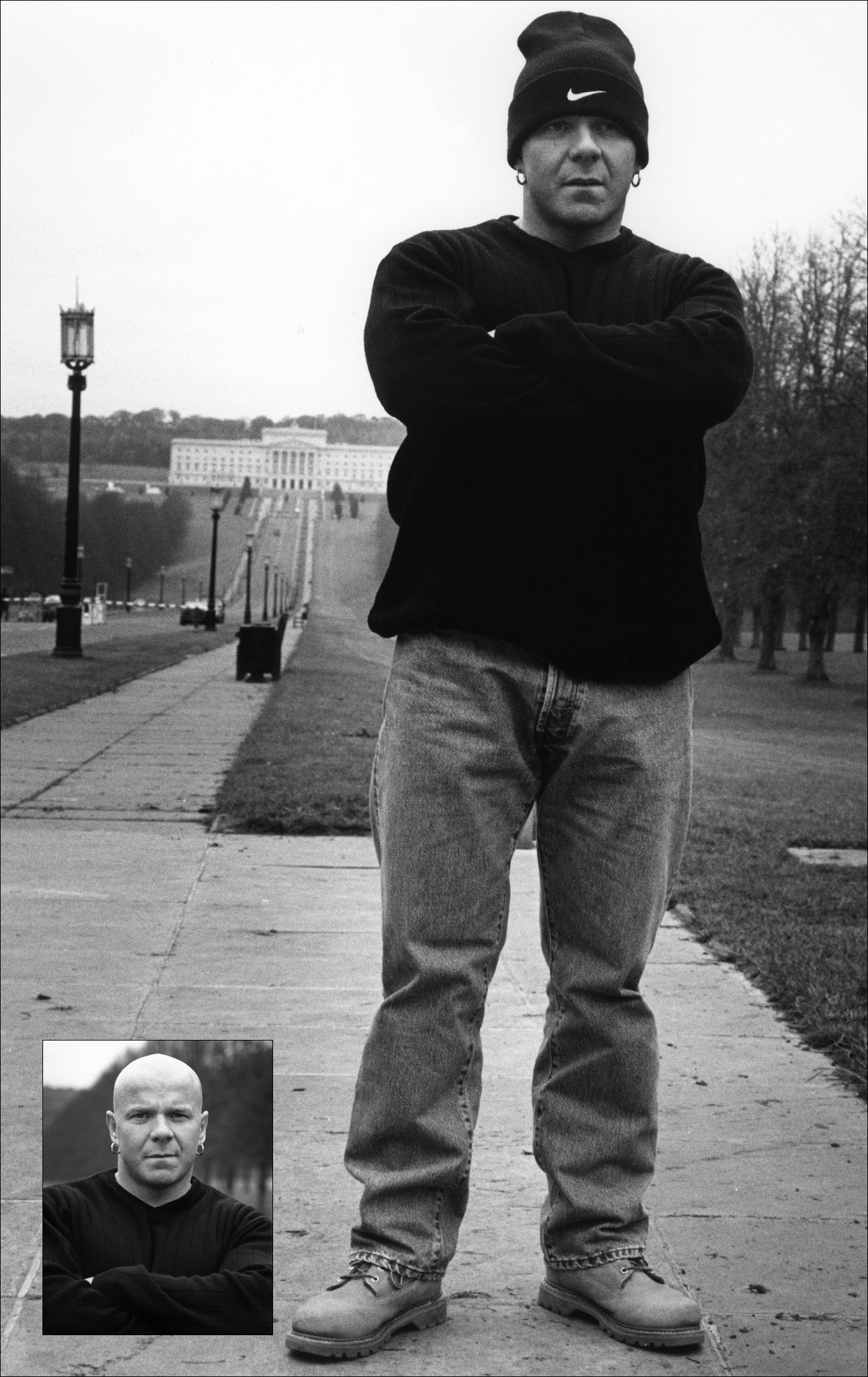

JOHNNY ADAIR

I’d heard about Johnny through the prison grapevine. Often, his name would crop up in conversation, but I’d never actually met him. In September 1999, I saw a small article in the Sun newspaper. There was a photograph of Johnny Adair being released from the Maze prison under the Good Friday Peace Treaty. He was the 293rd prisoner to be released and, as he walked, or should I say strutted, from the Maze, he looked every bit as dangerous as I’d heard he was.

I decided to include Johnny in Hard Bastards because he fitted the criteria: he demands respect and has a fearsome reputation, but mainly he can have a ‘row’.

It’s one thing to decide to put someone in a book, but then I’ve got to find them and convince them to take part.

I certainly didn’t want to put word out on the street that I was looking for Johnny, or indeed that anyone was looking for him. I know from experience that dangerous men are extremely paranoid.

Usually, if I want to contact a villain I make a call or two and I’ll have the number in my hand within hours, but Northern Ireland is not my manor. However, it was amazingly simple to find Johnny Adair. I rang Directory Enquiries and asked for numbers of political parties in Belfast. The operator gave me five or six different organisations and I started to make my calls. I explained each time that I was a journalist and wanted to speak to a man called Johnny Adair.

Instinctively, I felt that what I was doing was not ‘politically correct’, but I needed to find Johnny. There was a wall of silence. Every answer was the same, a curt, ‘You won’t find him here. You won’t find him there.’

Then I struck lucky. A lady I spoke to shiftily gave me a number and then hung up. I telephoned the number and asked to speak to Johnny Adair. A man with a strong, gruff Irish accent answered, ‘What do you want him for?’

I explained who I was and that I was writing a book. The voice on the line became softer, no longer hostile.

He introduced himself as Matt Kincade and said that he had read a couple of my books while serving time in the Maze prison and that Johnny Adair was a friend of his.

The whole exercise had been like looking for a needle in a haystack, and hopefully I’d found it! Within days, Johnny was in touch, but was reluctant to commit to any firm meeting. It was all very cloak and dagger. I told him I would travel to Ireland on 11 November. He gave me a telephone number and told me to ring it when I arrived. With that tiny snippet of information, I booked my ticket on the early-morning flight from Luton to Belfast.

My Easyjet flight to Northern Ireland was delayed – damn, I didn’t want to be late. I was going to meet Johnny Adair, or ‘Mad Dog’ as he is known. I sat on the plane waiting for take-off. I was fed up, it was the one interview I didn’t want to miss.

My friends and family had warned me not to go. They all said the same; that I was getting in too deep. I’d heard wild stories about Johnny Adair kidnapping Catholics and chopping them up. Each story was more bizarre than the last. I didn’t take any notice; to me it was all just hearsay.

Then I heard it from a good, reliable source that I really shouldn’t go; it was too dangerous and I was getting out of my depth.

Being the flippant fool that I am I just replied that I wasn’t Catholic or Protestant, but in actual fact I was Salvation Army. I’m a sunbeam, so as far as I was concerned, I was quite safe – or as safe as I could be.

We landed in Belfast on a cold, grey November morning. I made my way to the Stormont Hotel by cab. I was apprehensive, unsure what I was walking into. Maybe everyone had been right after all, and I was putting my life in danger needlessly. My minder stayed close to me the whole time and the photographer said nothing through fear.

When we reached the hotel, we ordered coffee in the lounge area and I rummaged in my briefcase for the small scrap of paper with the telephone number that Johnny Adair had given me. A deep Irish voice was waiting for my call. My instructions were to wait; Johnny would ring my mobile phone at 10.00am sharp. On the button, my phone rang – it was Johnny.

From the start, he was paranoid. He thought it was a set-up and said that if I wanted to speak to him then I was to go to the Shankhill Road.

I said no; I was a girl, I’d come to his back yard, and it was only right that he came to the Stormont Hotel to see me. He laughed, ‘I’ll be there in half-an-hour.’

I waited outside the hotel for Johnny to arrive. I’m used to dealing with paranoid men and I wanted to put Johnny at ease and, more than anything, to show him that it wasn’t a set-up and his life wasn’t in any danger. I told the photographer to wait inside and my minder to stay close.

Half-an-hour later I noticed a car circle the hotel. I watched it drive round once, and then again, before pulling up in front of me. Driving the car was a huge man. Sitting next to him was Johnny Adair. He climbed from the car, his eyes scanning everywhere. His minder did the same, his hand inside his jacket. Johnny walked towards me, his greeting warm and sincere. I introduced him to my minder, and he introduced me to his. Johnny’s accent was so deep that I had difficulty understanding him.

‘This is Winker,’ he said, pointing to his minder.

‘Sorry?’ I answered, with a puzzled look.

‘Winker … this is Winker.’

I shook his minder’s hand and said, ‘Nice to meet you, Wanker!’

For a moment there was a deathly silence. My minder looked away in horror. Winker’s face could have curdled milk. Johnny Adair roared with laughter and from that moment on the ice was broken.

In the beginning, the Irishman wanted to do the interview in the back of a car while it drove around the city streets of Belfast, but I convinced Johnny to go inside the hotel.

As we walked through the car park, a police car drove past. Johnny stopped dead in his tracks and glared at the patrol car. The officers inside looked at Johnny. I saw the panic in their eyes. Johnny stared daggers at them. They looked away. Johnny shot a glance at his minder and they both smiled.

We settled in the hotel foyer and ordered our coffees. I sat with Johnny on a sofa while our minders and the photographer sat some distance away.

Before he agreed to be in the book, Johnny wanted to know what it was all about. I explained about the book and showed him some of the other photos of a couple of men who were already included. In a strong Ian Paisley accent he said, ‘I’m not a gangster. I’m not a fighter. I’m a soldier of war – a fucking terrorist!’

The entire time I was in Johnny’s company, I felt that at any moment something could happen. I didn’t quite know what, but it was extremely dangerous being in his presence. His eyes flickered around the room all the time, scanning and surveying, watching everybody’s move – as did his bodyguard.

We started to talk and he became a little more relaxed until somebody sat behind me. His piercing blue eyes widened with alarm. He motioned to Winker. Suddenly they were on alert.

‘Do you know the man sitting behind you?’ he whispered.

I glanced over my shoulder and shook my head. It was obvious that Johnny was now uncomfortable. He never took his eyes off the man and Winker stayed close. He may have thought the man was from the security forces, the IRA or just a hitman who’d come to kill him.

It all seemed a little far-fetched until Johnny took his hat off and showed me the hole in the back of his head, the size of a 50p piece. Two months earlier, he’d been shot in the back of the head at a UB40 concert.

Then he lifted his sweater and showed me a hole in his side and one in his leg. He had been almost cut in half in another attack and there has been over ten attempts to kill him.

As Johnny talked and his story slowly unravelled, it was a tale not about money, or a grudge – Johnny Adair was fighting for what he truly believed in, which was for peace in Northern Ireland. I told him it was difficult for me to understand, because all we are used to seeing on the mainland are the atrocities that are committed in Ireland.

Before going to Northern Ireland, I didn’t have any preconceived ideas about Johnny Adair. But I didn’t expect him to be as ‘normal’, or as warm and friendly as he was. Everyone expects terrorists to be gun-toting thugs, but that’s not the case. Johnny spoke with great intellect. There was no malice or bitterness in his voice. It was the cool, controlled way in which he spoke that made him so utterly terrifying. He was normal – just like you and me. Before I went to Northern Ireland, I really hadn’t known what to expect, but I wasn’t prepared for the Johnny Adair that I met.

At the end of the interview Johnny agreed to have a photograph taken outside Stormont Castle, where the peace talks were taking place. We left the hotel and stood on the kerb, waiting to cross the busy main road. There were four lanes full of traffic. Every car in the four lanes stopped to let Johnny cross because they had recognised him. It was unbelievable. This is the power he has in Ireland.

Johnny was very amicable until the photographer asked him to turn his head and look at the castle. He refused. Johnny still wasn’t sure if it was a set-up. After the photo shoot, Johnny Adair was whisked away by his minder as quickly as he’d arrived. This is his interview.

BACKGROUND

I was born in the Shankhill Road area of Belfast, Northern Ireland. I’m the youngest of five brothers and one sister. As a teenager, I ran with a gang of Protestants. We’d roam the city centre searching for Catholics to hurt, for no other reason than their religion.

To people on the mainland, this may sound extreme but unless you live in Northern Ireland, the constant troubles are difficult to understand. I can only describe Belfast as two nations – Protestant and Catholic – and, believe me, the two don’t mix. It can be likened to the combination of nitroglycerine and a detonator – separately they are safe, but put them together and it’s dynamite! The wars were bloody and there were many casualties on both sides. I bear many scars and war wounds from my endless street battles. I think my reputation came from being a paramilitary leader, even before I was involved in the politics of it.

I was a young Loyalist, full of hate and anger, and saw Catholics as my enemy. I was a product of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. I grew up on the streets. Fighting Catholics was all I knew. I was a loose cannon, with no direction, until, that is, I joined the paramilitaries which gave me the direction I needed. It was then I realised why I was fighting: for peace in my country. Freedom is a passion I truly believe in.

It’s every human being’s fundamental right to be free and I’d fight until the last breath in my body to achieve this independence. I became ruthless in my quest and would stop at nothing. It was then I earned respect and got my reputation.

LIFE OF CRIME

I’ve been in and out of jail all my life, all for terrorist offences. In 1995, I was charged with ‘Directive Terrorism’ and was sentenced to 16 years. Directive Terrorism covers a lot of things but I can’t for legal and security reasons talk specifically about what I have done. In September 1999, I was the 293rd prisoner to be released early under the Good Friday peace deal.

WEAPONRY

Again, for legal and security reasons I cannot say what I specialise in.

TOUGHEST MOMENT

I’ve had many tough moments. There have been ten attempts on my life. I’ve been attacked with crowbars and hammers and stabbed twice, in the back and in the leg. I’ve been shot and wounded three times, once by the IRA. They ambushed my car and opened fire with an assault rifle. I was hit in the side of my body. But the worst pain I’ve ever experienced in my life was being shot at close range in the back of the head. It was the most petrifying moment I’ve ever had.

It was Autumn 1999 and I’d just been released from Ulster’s top-security Maze prison on parole. I’d promised to take my wife to a UB40 concert. We’d been looking forward to our first night out in many years. The kids were safely tucked up in bed and the babysitter was due at any time. As we were getting ready, there was nothing to suggest that this night was ever going to be anything out of the ordinary.

The atmosphere at the concert was electrifying. UB40’s rhythm was contagious. My wife and I swayed to the dulcet tones, ‘Red, red wine …’ It was good to feel normal again, if only for a moment.

BANG! The panic, the fear, the confusion. My wife screamed. I slumped to the floor with a bullet lodged in the back of my head.

IS THERE ANYONE YOU ADMIRE?

There are people I admire in Ireland who, in my eyes, are heroes. For instance, Michael Stone, the lone sniper in a Catholic graveyard. It’s difficult for me to explain and I certainly don’t mean any disrespect to London gangsters, but there are things terrorists would do in two days that gangsters wouldn’t do in their lifetime. That’s just a symptom of what’s happening in Northern Ireland. Atrocities aren’t being committed on a personal level, it’s aimed at the enemy and we believe the things we are doing are part of defending our people. If this means going to the extreme, then so be it.

DO YOU BELIEVE IN HANGING?

No.

IS PRISON A DETERRENT?

In Ireland, prison is not thought of as a deterrent, although a few years ago things were different and prison would have been harder but not these days. In Ireland, the paramilitary run the prisons, not the screws. We’re not criminals, we’re paramilitaries; we’re classed as soldiers. When we go to jail, we don’t do what they tell us – they do what we tell them.

Jail is not a deterrent, jail is an education. I learned more about life when I was in jail than I did in the whole of my lifetime when I was out.

In jail, you’re confined 24 hours a day and that time is spent alone. Outside time just passes you by and you never have time to stop and think about anything. Inside, you’re on your own, you analyse everything, you have all the time in the world to think, so it’s an education because everything goes through your head about what happened in the past, what might happen in the future. You analyse it all and educate yourself – it’s self-education. The fact that you’re in jail can be used to your advantage – if you want exams, you learn; if you’re into training, you use your time in the gym. That’s what I did. I went into jail out of shape and came out in the best shape of my life.

No, jail is not a deterrent, it’s an education. The only thing it does is take away your freedom.

WHAT WOULD HAVE DETERRED YOU FROM A LIFE OF CRIME?

Nothing would have deterred me because I fight for what I believe in, and when you believe in something you follow your heart.

I strongly believe what I’ve done is right so I have followed my heart. The only thing that will stop me from fighting is peace in my country.

WHAT MAKES A TOUGH GUY?

Only one man in a thousand is really tough. It’s natural – just in them. It’s not something you can share or explain, it’s just in you and people notice it and feel it.

IS THERE ANYTHING TONY BLAIR COULD DO TO HELP PEACE?

I think Tony Blair has done all in his power and I praise him for that. He has taken risks to please everybody. He has released hundreds of prisoners, both Loyalists and Republicans, so I believe he genuinely wants peace in Northern Ireland. I don’t think there is a lot more he can do. He has given it his best shot. From day one his support has been second to none, so I praise him, I really do.

JOHNNY’S FINAL THOUGHT

I have no regrets in my life except that so many people have lost their lives. It’s just a shame that peace didn’t happen in Northern Ireland 30 years ago. The peace that we have now and the talks that are presently taking place should have happened in 1969. Then there wouldn’t be over 3,000 people dead today, both Protestant and Catholic. That’s the only regret I have in the role that I played.

In September 1999, I was released from the Maze prison. I’d served five years of a sixteen-year sentence. Now I’m mellowing back into the community. Things have changed since I’ve been away – for the better. At last there is peace, but not for me.

When I was inside, I let my guard down. When I came out of prison I thought I was safe to go to a UB40 concert with my wife – I was wrong.

Now I don’t go anywhere without a minder. I have to live in a house that is protected like a fortress; all steel doors and security cameras. I have men sitting at the bottom of my street day and night to watch me and my family. Every day I wake up expecting something to happen and not knowing if it’s going to be my last day on earth.

The only thing that gave me a wee bit of breathing space was the Shared Government, but look what happened to that.

I don’t fear for myself, I fear for my family. I believe that it’s me with the death sentence hanging over my head. If I thought any different, I would have been up and away years ago.

First and foremost, I have no fear of the IRA or anyone else. If I did, I would be living in England. But I’m not, I’m still living in Belfast. I live 50 yards from a peace line that proves I have no fear of them.

The security forces nicknamed me Johnny ‘Mad Dog’ Adair. In their eyes, I’d killed over 40 people. They built up this myth that I was a Mad Dog who would kill anyone. People expect me to be a fanatical, violent, rabid dog. It’s not the case – I’m Johnny, and deep down inside I’m a good guy. But, do me a wrong and I’ll bring it to your own back yard. You’ll go to bed at night and barricade your front door in case Johnny ‘Mad Dog’ Adair comes looking for you.