Prairie Towns

Process and Form

Much contemporary discourse in environmental design has been concerned with trying to understand the values and processes that have contributed to the modern environment, with part of the debate concerned with the loss of distinctive regional and local identity and the construction of that identity.1 Where local and regional identity were once produced almost incidentally and resulted in distinct and unique landscapes, towns, and cities, the visual character of places is now more frequently produced, or protected, intentionally.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Darcy Thompson argued that the form of an object or organism is a “diagram of the forces” that have acted upon it. Although he was, at the time, referring to biological forms, the concept also applies to the form of a landscape, city, or neighbourhood.2 The growth of a cultural landscape, region, or city can be understood as the product of the forces acting upon it, and this form can be “read” and the processes explained.

Cultural landscapes refer to geographic areas modified by human activity or given special meaning by a group of people resulting in an area that is distinctive or definable in the form it presents or the values it reflects. They are illustrative of the evolution of human society and settlement over time, under the influence of the physical constraints and/or opportunities presented by their natural environment, and of successive social, economic, and cultural forces, both external and internal. Cultural landscapes are important sources, as well as receptacles, of individual and communal identity, and are often profound centres of human existence to which people have deep emotional and psychological ties.3 The values cultures place on the land are reflected in changing patterns of land ownership and land development, and consequently in the spatial, visual, and experiential qualities of the built environment. The evolution of a cultural landscape cannot simply be dealt with as a chronology of events; it also reflects the evolution of ideas and ideologies. This paper considers the evolution of Canadian prairie towns, from the settlement era to the present day, not as a strictly historical process but via several forces or form determinants through which ideas of place and identity will be discussed.

The Prairies, as a cultural landscape, have been affected by layer upon layer of human intention and action. Over the past few decades, the determinants that shaped prairie settlement at the turn of the twentieth century, such as the need for regularly spaced grain handling and service centres, have changed. Many towns have failed, but in the towns that persist the practicality, expediency, and distinctiveness of the early morphologies have given way to town planning practices and urban forms that raise concerns about sense of place and urban quality.4

Land

In his address to the Canadian Society of Landscape Architects in 1997, author and commentator Rex Murphy argued that Canadian identity is rooted in its various landscapes, and that our love for these landscapes is what unites us as a nation. He also suggested that we have yet to live up to our landscapes. This may be particularly true of the Prairies, which in some ways is a more challenging region than many.

The Prairies are a region of ethereal and ephemeral beauty, but also the kind of landscape that usually evokes strong feelings, either positive or negative, in people. It can attract and compel, but can also intimidate and repel. The detractors often speak of the Prairies as boring, flat, and tedious; others, however, are attracted to the beauty of the “austere land of violent mood.”5 The relationship between the Earth and sky is important, and the sense of space contributes to its character. The Prairies are both a place and a state of mind.6 This is powerfully expressed by writer Wallace Stegner, in his autobiography Wolf Willow:

The geologist who surveyed southern Saskatchewan in the 1870s called it one of the most desolate and forbidding regions on earth. Yet... I look for desolation and can find none.

It is a long way from characterless; “overpowering” would be a better word. The drama of this landscape is in the sky, pouring with light and always moving. The earth is passive. And yet the beauty I am struck by, both as present fact and as revived memory, is a fusion: this sky would not be so spectacular without this earth to change and glow and darken under it. And whatever the sky may do, however the earth is shaken or darkened, the Euclidean perfection abides. The very scale, the hugeness of simple forms, emphasises stability...

Desolate? Forbidding? There was never a country that in its good moments was more beautiful. Even in drought or dust storm or blizzard it is the reverse of monotonous, once you have submitted to it with all the senses.7

European settlement in the Canadian prairie region is historically recent, and it took place over a compressed period of time. Following scientific expeditions to the West during the mid-1800s, the new nation-state of Canada purchased Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company for the sum of 1.5 million dollars plus some land claims in 1869. The Canadian government envisioned the West for white agricultural settlement, despite its centuries-long history as an Aboriginal-European fur trade society and the longstanding presence of Indigenous peoples on the land. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the Government of Canada embarked on a massive promotional campaign to attract non-Aboriginal farmers to the West. Simultaneously, through the treaty and reserve system, Indigenous inhabitants were dispossessed of their traditional territories, and Métis resistance movements were suppressed, resulting in the dispersal of Métis homelands. The conversion of the prairie into farmland occupied by white settlers proceeded relatively quickly, with agricultural development following the spread of railway branch lines and the accompanying waves of homesteaders. The boldness of this vision, and the extent of the subsequent ecological transformation of the land, are staggering in their scope. The alteration of the original prairie ecosystem to today’s agricultural landscape is a significant man-made environmental change that is profound and permanent.

Landscape

The Prairies are vast and largely uniform, and only occasionally do features of strong relief occur. The topography falls away to the east from the boreal aspen forest and the rolling foothills, and three more-or-less distinct sub-regions make up the prairie region. These coincide generally with differences in elevation, soil type, moisture regime, and the native vegetation that existed before European settlement, and result in distinctions in the agricultural practices that proved successful and the density of population that remains.

Figure 1 The original topography and hydrography of the Prairies have been overlain by several patterns. (Drawing by the author)

In the last decades of the nineteenth century, the land was surveyed and subdivided according to the one-mile grid of the National Topographic System, and a grid road network connected the dispersed farmsteads. The regular grid survey was a convenient and effective way of subdividing and selling land. It influenced the size of farms, as land was settled, bought, and sold according to sections and quarter-sections, and has had a lasting effect on the location of roads and the distribution of the population. It is clearly discernible from the air, and the rhythm of the grid roads is sensed while driving any significant distance.

Figure 2 The cumulative effect of landscape, survey, and roads have produced the distinctive and much-marked prairie landscape. (Google Earth)

Settlement Pattern

The conversion of the Prairies into occupied farmland proceeded quickly during the late 1800s and early 1900s, with agricultural development following the spread of railway branch lines and the accompanying waves of homesteaders who were attracted by the Government of Canada’s massive promotional campaign.

Farmsteads were located close to the roads, and timber-frame houses and barns constructed, often through cooperative efforts. Although the Prairies were largely treeless, it was easier to transport wood than other building materials; entire houses could be ordered from mail-order catalogues, and frame construction required only carpentry skills. Clusters of simple and utilitarian wood sheds built over the first century of settlement are now mostly replaced with equally functional aluminum silos. The original and the newer objects on the agricultural landscape have an aesthetic and a geometrical simplicity that could provide a vocabulary for a regional architecture, but so far has yet to be tapped in any significant way.

Homesteads of one quarter-section (160 acres) were granted and until the end of World War I, homesteaders could purchase an adjacent quarter-section at a nominal price. The early process of land subdivision and homesteading produced the dispersed pattern of settlement, which is a distinguishing characteristic of the prairies. Over time, technological changes replaced horsepower with tractors, and combines did the work of harvest labour gangs so farmers could work more land. Pesticides and fertilizers have continued to improve yields and productivity, but the new machinery and chemicals require larger and larger contiguous fields in order to be used economically and efficiently. Quarter-section or half-section farms invariably proved to be inadequate, and larger farms, and consequently fewer farm families, are now more common.

Figure 3 Farmsteads were established on quarter-sections or larger parcels of land, setting up a spatial order and a social distance, and requiring each farmstead to deal individually with the extremes of climate, through, for example, establishment of trees as shelter belts. (Photo by the author)

As the Prairies were opened up, a rail system was required in order to help bring in the settlers and to move the agricultural produce. A well-developed transportation network was necessary to assert Canadian sovereignty over the adjacent United States who had interest in the lands, and also over Indigenous and Aboriginal territories, and to promote the economic base of the region.8 The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) negotiated a contract with the Canadian government that provided a land grant of 25 million acres, along with cash, the cost of surveys, and other concessions, which assisted it economically and gave the railway a powerful position in western development that it retains in many ways to this day. The railway was also conceived for its political mission of uniting the country, and its presence, although now much diminished, still has nationalistic symbolic meanings.9

Contrary to traditional locational theory whereby gradual and random incremental growth transformed a crossroads hamlet into a town or city, western railway-town establishment and development occurred according to railway company directives.10 Railway routes were determined taking into consideration such factors as grade, terrain, hydrography, and agricultural potential of the area, and they inscribed a second pattern upon the survey grid. Along the prospective route, land was reserved, the right-of-way purchased, and then from the reserved blocks, townsite location would be considered. Sidings were located at six- to ten-mile intervals, a convenient distance for hauling grain with a horse and wagon, and some of these sidings would become townsites.

The ones that were destined to become towns became distribution points for agricultural implements, feed, coal, lumber, and general merchandise. Larger centres developed at divisional points approximately 110 to 130 miles apart, which was the distance a locomotive of the day could travel without refuelling. These points were where engines and train crews were changed, and they required additional services, such as hotels and banks, and were more actively developed by the CPR. The resulting dispersed nature of the towns (and of the homesteads) established a social distance and a sense of isolation, but also a system of co-operation and mutual care, where the towns functioned for the farmers and ranchers as important social, as well as service, centres.

Transportation technology change has probably had a greater impact than any other force on settlement patterns: the period of establishment and exploitation depended upon the establishment of the railway network, which began in the 1870s and was complete by the early 1930s. The purpose of towns during this period was utilitarian. Construction of a network of highways and improvements of the prairie road network began in the 1930s, a period that saw either the consolidation and expansion, or the collapse, of prairie towns; those that remained usually became established communities. Highway and air travel eventually began to dominate passenger and freight activity. Until the 1950s road networks were generally locally oriented, and the highways were more closely linked to the United States than to neighbouring provinces. In 1950, construction began on the Trans-Canada Highway to provide an east-west route linking the entire country; Highway 1 was opened in 1962. Over time, the inter-city highways were paved and widened, and the grid network of country roads was improved. The Trans-Canada Highway is an element of great importance to the Prairies. It links the cities, and is the first in the easily perceived hierarchy of roads. Rail passenger service was discontinued beginning in the 1970s, and grain handling and transport entered a process of rationalization that introduced new patterns and forms that create another layer on the land.

The concept of distance has a profound meaning on the Prairies—major centres are between 200 and 300 miles apart, and high-speed driving is required to comprehend the spatial order. Travel from the main divided highway to a secondary highway to a gravel or dirt road takes one from a high-speed ribbon of whizzing cars and trucks to a place where space and time are measured in quarter sections and grid roads. Unless one makes the effort to get off the Trans-Canada and onto one of the smaller tributaries, the highway remains as its own place—an asphalt conduit giving few hints of the subtle richness of the landscape that it slices through, or of the population centres that might be located there.

Railways and the Grain Elevator System

To transport grain to distant markets, more than a railway was needed. Grain elevators combined with and depended upon the railway system, enabling vast amounts of wheat and other grains to be marketed in a relatively cheap and efficient manner. Farmers hauled their crops to the railway siding, where they would be stored in an elevator until loaded on a train, to be transported to a terminal grain elevator at a larger centre.

Grain elevators were painted with the elevator company colours and logo, and usually the town name in large letters near the top. Towns were therefore recognizable from a distance, and the grain elevators were the most prominent buildings in every town, symbols of relative wealth and prestige. Ronald Rees described how the elevators suited the prairies: “The prairie landscape is a landscape of extreme dimensions, described by Frank Lloyd Wright as ‘a great simplicity,’ and it calls for extreme, yet simple, forms. Two seem particularly suited: the low, spreading structure, submitting to the prairie; and the vertical, opposing its dominating horizontality. Only the grain elevator really belongs—its height, firm lines, and strong colours harmonising with the bland prairie and parkland and taking full advantage of the abundant sunlight. It is a self-assured form, confident of its function.”11

Figure 4 A long row of elevators in communities such as Vulcan (top, photo by the author, 1993) once signified their regional importance (Vulcan was the largest among the regularly spaced string of places on the line between Calgary and Lethbridge: Mazeppa, Blackie, Eltham, Brant, Ensign, Vulcan, Kirkaldy, Champion, Carmangay, Peacock, Barons, Nobleford, Whitney). Only one elevator remains within the town of Vulcan today (middle, photo by the author, 2008). The new order is represented by concrete structures no longer situated within the towns (bottom, photo by the author, 2005).

Where the system of towns was originally formed and responded to specific and directed forces, they are now part of the larger and more coarsely grained international community. Over the past few decades, the determinants that shaped prairie settlement at the turn of the century, such as the need for regularly spaced grain handling and service centres, have changed. Transportation methods have shifted from rail to automobile and freight truck, and the network of railways is in decline.

Concurrently, competition and the mechanization of agricultural practices have favoured large corporate agribusiness over the family farm, and the prairie economy has undergone a major structural transformation. Improvement in roads and truck transportation, and a shift to custom hauling of grain which utilizes larger semi-trailer trucks and covers longer distances, means that the short-distance elevators are no longer required. New high-throughput elevators (HTE’s or “cement plants”) are spaced fifty to 100 miles apart, with catchment areas of a radius of fifty to seventy-five miles and a much larger capacity. Overlap is common, as agri-businesses compete. These massive structures can be more efficiently operated outside of town where huge trucks can access them more easily, therefore this process is now disengaged from, and independent of, the settlements.

As more and more of the high-throughput elevators are constructed, a new order is emerging. Although massive in scale, they still exhibit the same functional efficiency and integrity typical of agricultural buildings. Many of them employ distinctive company colours, and the structures are visible from a great distance. Perhaps this new form will come to represent a new spatial order, and visually express it in the same way as the system of wooden elevators did for the first century. Nearly 6,000 country grain elevators were standing in the 1920s and 1930s; since then their numbers have steadily decreased, as the need for close spacing of elevators became obsolete. In the late-twentieth century, this shift accelerated; from 1982 to 1992 the number of country grain elevators in the Canadian prairies fell from 2,934 to 1,498; and in Alberta, where there were over 500 elevators standing in the early 1990s, there are now fewer than 100.12 Most of the wooden elevators that still remain are either privately operated, or are vacant. The loss of this highly visible and meaningful symbol of the prairies has spurred efforts to save elevators and to find other uses for them; however, their decline in numbers continues.

The impact of this transformation is important to local and regional contexts. The presence of grain elevators gave the Prairies visual identity and legibility, and provided one of the only ways of orienting oneself on the landscape that otherwise does not have many visual landmarks. On the flat Prairies, grain elevators were the first structures to be seen from a distance, signalling clearly the town’s function as an agricultural service centre, emphasizing its location on the rail lines, and signifying refuge and the presence of other people in the otherwise empty land. The potentially disorienting vastness of the Prairies was made human and tolerable by those visual landmarks. Towns which were otherwise largely invisible on the flat plains were identified by the number and colour of the elevators; without the elevators, the towns disappear into the horizon. The elevators gave structure and order to the towns, which now have few differentiating forms; most towns are now clusters of houses and commercial buildings, and there are few visual clues as to the reason for their presence or location. As a result, the social and economic life of the towns has suffered, since farmers no longer have to travel to the towns to ship grain, and at the same time socialize, buy goods, and frequent cafes.

Townscape

Sir Sanford Fleming, at one time the chief engineer and surveyor for the CPR, gave directives regarding stations, town plots, roads and crossings. In his Report on Surveys on the Canadian Pacific Railway, produced in 1877, Fleming proposed a model plan for town layout, with the station at the centre and the streets radiating out from it.13 Although it was never realized, and although the CPR did not appear to have a clear policy on townsite layout, subsequent town plans located the station at the centre, with the commercial district huddled around it and the settlement developing outward from there. Plans that could be easily expanded were the norm. The rectangular grid formed the base for general townsite layouts; other plan arrangements were viewed as difficult to use due to their increased complexity of survey.14

The major elements used to generate railway town form were the presence of a siding, the railway station, and the main street. The main street was characterized by its larger dimensions, sixty-six feet (the length of a surveyor’s chain) or often ninety-nine feet wide, with narrow commercial lots of twenty-five feet in width as compared to residential lots of fifty feet. Towns conformed to a simple structure. There were two linear functional axes—an industrial axis along the railway tracks, and a commercial axis along Main Street, either parallel or perpendicular to each other, depending on town plat. The town centre grew around that intersection in a grid pattern of blocks. Residential streets typically had sixty-six-foot allowances, and included sidewalks and treed boulevards.

Characteristic features were grain elevators along the railway line, the railway station (across the tracks from the elevators), Main Street perpendicular or parallel to the rail line, and a grid network of streets. The attractiveness of the railway stations as social centres increased when railway agents began to plant gardens, a practice that began voluntarily but eventually became company policy. Station gardens were considered valuable in convincing arriving settlers of the fertility of the land, and often gardens were planted in a way to appeal to their cultural values and make them feel more at home.15

Figure 5 The town of Olds, Alberta ca. 1920, typical of prairie railway towns, is legible as a grain handling centre, as a component of the railway system, and as a dense and leafy settlement on the otherwise sparsely inhabited prairies.16 (Glenbow Archives)

Early town form was expressive of an “inside-out” development, a form that also reflected how the town was experienced. Goods and people typically arrived at the railway station, and worked their way outward through successive layers of public function. The railway station was not only the first thing that people saw, it was the social and cultural heart of the town, and was imbued with many layers of meaning and association. From the railway station and grain elevators, one could easily locate services such as hotels, banks, and stores. The street patterns were legible, and the size and organization of the buildings were harmonized. The main street and adjacent commercial streets constituted the heart of the town, and were more than just streets, services, and spaces: they were places, and they were a measure of a town’s success and prosperity.

In the late decades of the 1900s, and paralleling the changes in grain-handling technology, passenger travel on the Prairies shifted from rail to automobile, and freight transport from train to truck, and the railways experienced a general decline. The transition has generally not been graceful; as railway stations became obsolete, distinctive buildings were either demolished or replaced by utilitarian concrete sheds, the gardens are long gone, and the public and social function of the stations and gardens have not been replaced. The land adjacent to the railway stations is often used for parking lots, or is left vacant, creating what Trancik calls “lost space.”17 The CPR owns most of the land adjacent to the railways, which in most towns means that a large strip of land through the centre of the town is in the control of one very powerful absentee land owner. These vacant sites that are left in the middle of the town are destructive to the town’s character and erode its functional cohesiveness.

Figure 6 The railway station in Virden, Manitoba has been vacant for many years (top); the original station in Olds, Alberta (a similar structure to Virden’s) was replaced by a concrete block shed in the mid-1960s (bottom) after the railway garden adjacent to that station was bulldozed and a strip mall (poignantly named “Garden Park Plaza”) and parking lot were built in its place. (Photos by the author, 1991)

Main Street

Prairie towns, while certainly not identical, had a recognizable vernacular, particularly of Main Street, that was expressive of the traditional materials and ways of building. Timber frame construction, building right up to the property line, doorways that were set back, large storefront windows, and false fronts to present the largest facade for advertising were all features of Main Street. These characteristics are all expressive of the environmental conditions, of the light, and of the culture—the way of doing and being that is easily recognized as being of the Prairies.18 The architecture of Main Street typically consisted of one- or two-storey buildings with false fronts that concealed the pitched roof behind them, presenting an impression of size and solidity. Most were wood, although significant buildings such as banks were constructed later of sandstone or brick.

Traditionally, there were a limited number of building materials and techniques, and there were consistent ways of doing things, so that the streets hung together as cohesive townscapes. However, there was enough variety from town to town, in terms of local variations in building materials and local businesses, for each town to have a distinct identity; as other materials became available and as traditional construction techniques evolved or new ones were imported, various eras became identifiable through the historic record of built form. Although there was change, it was gradual and related to what came before; and as the streets and public spaces provided an underlying unifying structure, there was continuity.

Many historic downtown commercial centres began losing business in the last decades of the twentieth century to highway strip malls or to out-of-town shopping centres, which are better positioned to capture the transient automobile traffic. This resulted in local economic loss, in a decline in social vitality in the town centres, and in corporate homogeneity replacing local individuality and character. The issue received significant professional and public attention.

As early as the mid-twentieth century, the decline of the prairie town economy and image was being recognized. The cultural heritage of the small town, embodied in the historic business districts, and its economic vitality, traditionally localized on Main Street, was threatened by the strip malls that were springing up along the highway entries. Coupled with this was the visual deterioration of the historic commercial and residential areas, as original buildings were demolished or renovated beyond recognition, or mutilated and obscured by signage and additional layers of “modernizing” features.

Figure 7 The Main Street in Olds, Alberta is recognizably of a prairie town: the false-fronted buildings facing right up to the property line, the local businesses, and the angle parking are typical and characteristic. Although there was variation in materials and design, the buildings formed one cohesive whole (top, photo c. 1950 by D. Becker). The main element of the highway strip mall ca. 1970 in Olds (middle, photo by the author) is the large parking lot in front. The latest variation is the more recent construction of big-box stores, in this case a Walmart on the edge of the town of Pincher Creek, Alberta (bottom, photo by the author).

Attempts to address the economic decline of Main Street businesses began in the 1970s, most notably and successfully by the federal and provincial Main Street Programs, which focused revitalization around heritage resources. In the initial Main Street Canada projects, seven communities with important heritage resources were selected. From 1981 to 1985, Heritage Canada Foundation coordinators worked with the business communities of these towns to become more effective in competing with the strip malls, not by “promoting the prettification of Main Street” but by “encouraging communities to restore the life that was already there, by working with the people who were already there.”19 By 1990, over seventy communities throughout Canada had become involved in the second phase of the program. The goal of the program, “to combine preservation techniques with economic and social revitalization of a community’s commercial centre through a gradual process of incremental change,” involved organization and management, marketing the downtown and individual businesses, as well as urban design and economic and commercial development strategies.20

Figure 8 The Main Street Canada pilot project in Fort Macleod, Alberta attempted to combine image enhancement through period restoration with marketing strategies. The aim of that project, started in 1982, was to restore the image of the commercial buildings in the downtown historic area to an approximation of the 1920s, while improving their usability for business. The program also had economic benefits, and Fort Macleod’s restored Main Street continues to be one of the town’s primary tourist destinations. (Photo by the author, 2002)

In 1994, Heritage Canada Foundation withdrew from Main Street Canada, and main street improvement programs have since then been maintained at the provincial level. The Alberta Main Street Program was created in 1987, and has more recently adopted the document “Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places in Canada” as its guide. It works with the Municipal Heritage Partnership Program to help municipalities manage their historic places.21 As of 2009, the program had undertaken work in twenty-three communities.22 Main Street Saskatchewan23 is a new project through which four communities (Wolseley, Indian Head, Maple Creek, and Prince Albert) were selected in 2011 to pilot a demonstration program, and the Hometown Manitoba program24 was introduced in 2004 to provide funding in two categories: Meeting Places and Main Streets; since then it has provided funding through a competitive process.

Figure 9 Especially notable in High River are some individual properties that reflect many of the qualities and characteristics of Main Street (which are now also considered to be some of the qualities of good urbanism) including a small set-back, permeable facade (entry off the street and large windows), mix of uses (including commercial at grade and residential above), and compatible materials—and all of this within a contemporary architectural envelope. (Photo by the author, 2006)

In addition, initiatives by property owners and developers have attempted in various ways to reflect historic ideas, with varying results and implications. Positive examples can be found in High River, Alberta, which has managed to maintain a viable downtown commercial area through a combination of economic initiatives, streetscape improvements, Main Street Programs, and design guidelines, despite competition from newer commercial areas along the highway entries.

In some cases, the enthusiasm for revitalization led to the creation of forms that have little to do with the actual history or context of the town. For example, the town of Battleford, Saskatchewan had Victorian and Edwardian beginnings, but has been “updated” to a Wild West theme, with false-fronted cedar-sided buildings complete with hitching posts.

Vulcan, Alberta, an agricultural town established in the early 1900s, was once renowned for its row of nine grain elevators, distinguishing it as a major regional grain handling centre. As the elevators were demolished ca. 1970 and its commercial main street declined, the town struggled to maintain its attractiveness as a place to live, and its identity. After Main Street improvements in the early 1980s did little to stimulate its economy, Vulcan embarked on a series of programs, all linked to the TV show and movie series Star Trek. Since approximately 1990, Vulcan has attempted to distinguish itself through its name, which it shares with the fictional planet Vulcan—birthplace of the show’s Dr. Spock—and the town’s website now identifies it as the “official Star Trek capital of Canada.” The tourist information booth is in the form of a spaceship, and people visit for the opportunity to photograph themselves alongside plywood models of the Star Trek crew or to buy a set of plastic Vulcan ears. Tourists are attracted to what has become the yearly “Spock Days” festival, and year-round to the attraction of the tourist centre and town murals that depict scenes from Star Trek.

An even more perplexing example is Langdon, Alberta; it is important to briefly review the history of its evolution in order to comment on current developments. Langdon was established in 1883 on a branch line of the CPR. It grew to a population of 800 by the early 1900s, and to 2,000 by the early 1920s. Main Street was located perpendicular to the rail line, and a couple of blocks of commercial buildings were developed to the north. However, due to a number of issues including high water table and poor drainage, and construction of a duplicate rail line ten kilometres to the southeast, it lost its prominence, and declined to 100 residents by 1950.

Figure 10 In Langdon, construction of a building is intended to appear as a false-front commercial building and replicate the Main Street type (top). A boardwalk on top of a concrete sidewalk, a brick veneer facade, the separated buildings (to conform to the current fire code), the parking lot in front, and the “1908” sign are all peculiar elements (bottom, both photos by the author). This development has injected vitality into the hamlet and provides some commercial and professional services, but one wonders what the residents make of this new “history.”

Langdon lost its Village status in 1975 and was designated a hamlet. It was not until construction of a new sanitary sewer line in 1983 and improvement of the local highways that the town was again seen as being a desirable place to live. With the expansion of Calgary’s suburban edge, Langdon became viable as a bedroom community, and started a new period of growth in the 1990s and 2000s.25

A mixed-use development nearing construction completion as of 2011, is designed as a reconstruction of Langdon’s Main Street in 1908, albeit in a different location several blocks north of the original town centre and 100 years after the fact. Also different is the building type; where the original Main Street conformed to the Main Street typology of individual but linked false-fronted mixed-use buildings, the new development is essentially a strip mall on the main highway entry and with a parking lot in front. It is private property, and not a public street.

Although the Main Street and similar programs can bring some economic benefits to a town, period restoration can also result in preservation of the past, but prevention of the future.26 The spatial structure and visual symbol of the prairie town embodied during its early development became a cultural icon, even though prairie towns evolved significantly after this period. Main Street conservation programs became fixated on the early-twentieth-century era as the epitome of prairie town development, and one to which the town should return. However, in reality, towns continued to evolve beyond that original typology.

The Highway Strip

Concurrent with the decline of the railway was an increase in importance of highway travel and transport and the development of the highway commercial strip. Real estate opportunities often became a driving force in town development, where the most important quality of an environment is its “highest and best use.” These values and ways of thinking contributed to the shift of the commercial activity from the historic downtown core to the highway strips in order to take advantage of lower land costs, direct access to highway traffic flow, and to enable more parking to be provided. Coupled with this were changes in shopping patterns; regional shopping centres and superstores have been located in a number of towns, where they are able to attract the more mobile rural customers within a regional catchment area. These large developments further erode the commercial viability of local downtowns, and their morphology seems more suited to city suburbs than to small towns.

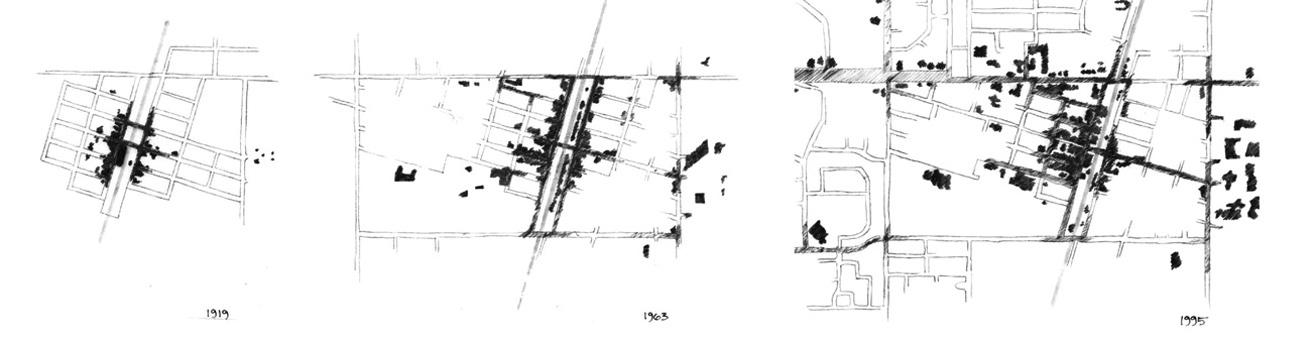

Figure 11 Impressionistic drawings of Olds, Alberta illustrate how the central commercial heart of the town (darkest tone) has now become dispersed. Drawings by the author.

As the highway gained importance and the railway concurrently declined, the experience of the town is now “outside-in.” The “entry” point is the highway strip—a series of fast-food restaurants, service centres, automobile dealers, and big box stores that are positioned to capitalize on the new traffic patterns. Although usually criticized, highway strip developments are the logical developments of the evolution of transportation and technology, and their deliberate urban design as a travel corridor to communicate regional and local identity and as a gateway into the town is, so far, a missed opportunity.

Many people are still attracted to small towns,27 presumably for their distinctive environment and culture; however, the new pattern of development threatens to homogenize and transplant city suburbia to the country, destroying the very features that make smaller places desirable. In strip malls and big-box developments, there is no contact with the street as a social environment; rather, the street becomes a separator, as parking must be visible to attract customers. The parking lot, rather than the street, becomes the most likely opportunity for informal social encounters, a situation more like that of suburbia than the small town.

Road Layout and Neighbourhood Structure

Although the original railway grid plan can be criticized for its own autocratic system and for its unresponsiveness to local variations of topography, it defined the form of the prairie town and is a historical expression of the development of the west, as well as a convenient and effective method of subdividing and selling land. It is also an urban form that is legible and permeable, particularly in terms of the degree to which an environment offers a choice of ways through it, and from place to place. If attention is paid to issues of scale and variety, the grid often contributes to a high-quality urban structure and way of life.

The original continuous grid resulted in a connected and cohesive town fabric. Towns which have experienced development since the 1950s are now composed of a gridded core surrounded by newer neighbourhoods of cul-de-sacs, crescents and collector roads. The result is a jarring discontinuity—in street layout, building density, building setback, and even sidewalk dimension and species of street tree—as the new developments have been imposed with little regard for their compatibility with the existing fabric. The shift in road layout and streetscape appears as fractures in the town form. Varying street alignments and changes in building density have resulted in parts of the town becoming segregated from each other. It is difficult to find any rationale for unnecessarily interrupting block pattern and streets, other than the tendency to attempt to spatially distinguish one neighbourhood from the other for marketing purposes. A more coherent vision of town form, including ideas of road alignment and articulation, should be expressed in the Municipal Plan so that new areas can be grafted onto the old rather than existing in isolation.

Figure 12 Town development in the case of Olds, Alberta up to the middle 1960s conformed to the subdivision pattern aligned with the railway grid. The government road allowances contained the town; the railway station, grain elevators and Main Street formed a cohesive town centre. By the 1990s, the town consisted of the original railway grid, but now with several developments of varying densities and configurations surrounding it. As the town expanded beyond the highway grid, new subdivision patterns followed generic engineering models for suburbs, rather than grafting on to the established streets. Streets do not line up, and town neighbourhoods are cut off from each other. Drawing by the author.

In the course of this evolution, changes also occurred at the scale of the street. Where the town had been comprised of narrower streets with treed boulevards and small setbacks, the newer developments consisted of wider streets, wider sidewalks, no treed boulevards, and houses set further back from the sidewalks. Traditional back lanes are usually omitted, and large garages, rather than front porches, dominate the street facades. These newer street types are more suited to vehicles than pedestrians; later evolutions do away with sidewalks and street trees, negatively impacting the social and public function of the street.

The earlier grid, with the smaller setbacks and treed boulevards, helped to create a feeling of being inside a continuous town. The newer subdivisions, with the emphasis on the individual lot and the lack of unifying elements such as street trees, transfer the feeling of “insideness” to the house. The end product is a suburb—a low-density, self-contained neighbourhood—rather than a continuous town.

Figure 13 Three streetscapes—all with sixty-six-foot rights-of-way—representing three phases of residential development in Olds, Alberta. In the historic grid (top), there is a clear definition between public and private space, the sidewalk is an important public component, and trees are a structural element. In subsequent development (middle), regular street tree plantings have been eliminated, the human scale has declined, and the sidewalk is a much less comfortable place for walking. In the newest developments (bottom), the street is most important as a device for moving and storing cars; the definition of private and public has become ambiguous, and trees are rarely included. (Photos by A. Nicolai, 1994, used with permission)

Where to Next?

Although it was often previously thought that small towns would be destined for extinction as they lost their traditional economic base, such predictions seem to have been based on general statistics and short-term trends, and overlooked both regional considerations as well as the ability of towns to alter the nature of their service roles and/or attract new economic activities in order to survive. They also may not have foreseen the infrastructure improvements that made highway commuting much less inconvenient. The function of the prairie town has changed, but it remains an integral and vital part of the Canadian West.

There are two somewhat conflicting scenarios taking place in the rural prairies. One is the population redistribution caused by agricultural and transportation technology changes which have favoured larger centres.28 The other is an apparent preference many people have for small-town or country living, contributing to a counter-urbanizing process identified by Bollman and Biggs and continuing today.29 This is most pronounced in Alberta, and in towns that are within easy commuting distance of larger cities. Alberta’s population growth was 10.8 percent between 2006 and 2011 (compared with Canada’s growth of 5.9 percent during that same interval, Manitoba’s of 5.2 percent, and Saskatchewan’s of 6.7 percent (up from the 2001–2006 decline of 1.1%). Some of the towns within one hour’s commute of Calgary had the following population growth rates between 2006 and 2011: Black Diamond 19.2 percent, Carstairs 27.5 percent, Didsbury 14.1 percent, High River 20.6 percent, Langdon 43 percent, Olds 13.5 percent, Okotoks 42.9 percent.30

But what will these towns become next? If sense of place and authentic identity are important ideas, then this question should be considered carefully. As Michael Hough observed, “the question of regional character has become a question of choice and, therefore, of design rather than of necessity.”31

Canadian prairie towns are distinct, and are the product of particular geographic and historic processes. Many emerged over a short period of time in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in response to specific needs and as a manifestation of an anticipated future white settler society. The patterns and structures that were first laid upon the land responded to issues of function and expediency. Just finding an easy way of subdividing and selling land, transporting people and goods, and keeping out the elements resulted in simple utilitarian landscapes and structures. But now, with technological innovation and access to global markets, almost anything is possible, including many versions of historical and pseudo-historical themes. But their ability to continue to contribute to a sense of place may not be appropriate or desirable, assuming that we as a society continue to value the distinct and the authentic.

Place image was once a direct outcome of the forces acting to produce it; the line between process and form was direct, and “reading” a landscape was an activity that could provide true insights. Many recent developments are more obscure, and in some cases completely indecipherable. It is more difficult for a resident or visitor to a place to be able to understand where the buildings and spaces came from, and why they take the form that they do.

While historic conservation programs have been effective in preserving physical pieces of the past, they have tended to be site- and period-specific (rather than treating history as a dynamic process which affects the entire town); they also do not provide sufficient guidance for new development within a modern context, but tend to propose one- or two-dimensional solutions to multi-dimensioned issues.

Change and transformation are part of landscape and settlement evolution. When they build on and reinforce qualities and patterns that are considered to be distinctive and supportive of high-quality physical environments and a high-quality way of life, then change is positive. When transformation results in a loss of identity and a decline in quality, however, those changes need to be questioned. What do we do as technology changes, and when railway stations, or grain elevators, or mills, or mines become obsolete? What do we do with our landmarks when they are no longer viable and have become part of history? It is important to find ways to reconcile local and regional identity with modern aspirations, and if the questions are properly framed, then perhaps elements such as highway commercial developments, town entries, abandoned railway lands, and obsolete agricultural structures could be approached as opportunities for celebration of place and acknowledgment of contemporary conditions.

The ingredients for cohesive and place-specific town form are often found in the historical record. Many elements of the early towns, such as the Main Street typology, the permeable and coherent grid block pattern, walkable residential streets, and the development of a town centre are what urbanists have now been advocating for several decades, following the unsuccessful post–World War II era characterized by excessive land use zoning, urban clearance, and rationalization of services. There are also important landscape approaches and elements suited to the Prairies that first arose in response to the need to make it home—and then to cope with droughts, winds, and the peculiarities of the prairie environment—including the simple elements of trees, shelter belts, and many practical ways of coping with a finite water source. These urban and landscape elements are great sources for planning and design.

Reviving or maintaining a sense of place does not lie in the preservation of towns as museums or the creation of themed environments. It is important not to romanticize or to give way to a nostalgia for what is often a largely imagined past. But it is also true that when historic urban forms are recreated, they are not without social and political meaning, even though they may be removed from their original context. The inherited meanings of these forms, therefore, may be used to provide a legitimizing vocabulary for newly created buildings and public spaces. This can likely only be done successfully if it is approached honestly—by understanding the fundamental elements of the Main Street typology that contributed in a positive way to town form and town life, and learning to reflect those in new construction rather than simply replicating the facade image. If this could be done successfully, then new buildings could be signed as the actual date of construction, and not, as in the case of Langdon, as 1908. Thus, in the accumulated history of the town, expressed in its public spaces, buildings, landscapes, and institutional forms, a typology could be developed that would go beyond the simple relationship between form and function, to express a continuing tradition of morphology and of community life.

Notes

1 See for example Michael Hough, Out of Place (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1990); Edward Relph, The Modern Urban Landscape (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1987).

2 Darcy Thompson, On Growth and Form (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1917, repr., 1961).

3 Edward Relph, Place and Placelessness (London: Pion, 1976)

4 Ronald Rees, New and Naked Land: Making the Prairies Home (Saskatoon: Western Producer Books, 1988); Gerald Friesen, The Canadian Prairies: A History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1984).

5 Ronald Rees, “The Prairie: A Canadian Artist’s View,” Landscape 21, 2 (1977): 31.

6 A Region of the Mind, ed. Richard Allen (Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center, 1973); Rees, New and Naked Land; Neil Evernden, “Beauty and Nothingness: Prairie as Failed Resource” in Landscape 27, 3 (1983); Sharon Butala, The Perfection of the Morning: An Apprenticeship in Nature (Toronto: HarperCollins Publishers, 1994).

7 Wallace E. Stegner, Wolf Willow (Toronto, Penguin Books, 1962), 6–8.

8 R.F. Legget, Railways of Canada (Vancouver: Douglas and MacIntyre, 1973).

9 See Legget, Railways of Canada; and J. Edward Martin, Railway Stations of Western Canada (White Rock, BC: Studio E, 1980) for further reading on Canadian railways; and Edwinna von Baeyer, Rhetoric and Roses: A History of Canadian Gardening, 1900–1930 (Markham: Fitzhenry and Whiteside, 1984) for a chapter on railway gardens.

10 John Reps, Cities of the Way West: A History of the Frontier of Urban Planning. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979), 10.

11 Rees, “The Prairie,” 32.

12 A. Paavo, “Never say forever,” Briarpatch (June 19, 1993): 13.

13 Legget, Railways of Canada.

14 A. Holtz, “Small Town Alberta—A Geographical Study of the Development of Urban Form” (MA Thesis, University of Alberta, 1987), 66.

15 Von Bayer, Rhetoric and Roses, 14–33.

16 Glenbow Archives, PA-3689-632.

17 Roger Trancik, Finding Lost Space (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1986).

18 See Donald G. Wetherell and Irene R.A. Kmet, Town Life: Main Street and the Evolution of Small Town Alberta, 1880–1947 (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1995); and Beverly A. Sandalack, “The (sub)Urbanisation of Prairie Towns,” Prairie Forum 27, 2 (2002): 239–248 for further discussion of town form.

19 Deryk Holdsworth, ed., Reviving Main Street (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1985), ix.

20 John J. Stewart, “A Strategy for Main Street,” Canadian Heritage 40 (May-June 1983): 5. The program is described in considerable detail in Holdsworth, Reviving Main Street. See Andrei Nicolai and Beverly A. Sandalack, “Hometown: Urban Design Issues in the Canadian Prairie Town” in Issues in Canadian Urban Design, ed. C. Charette (Winnipeg: Institute of Urban Studies, 1995), 149–182; and Beverly A. Sandalack, “Continuity of History and Form: the Canadian Prairie Town” (PhD Diss., Oxford Brookes University, UK, 1998) for a discussion of these programs and some of their effects.

21 http://www.albertamainstreet.org/ Accessed July 2011.

22 Heritage Canada Foundation for Saskatchewan Tourism, Parks, Culture and Sport, Main Street Programs Past and Present, March 2009 (http://www.tpcs.gov.sk.ca/MSProgramHCF).

23 http://www.tpcs.gov.sk.ca/MainStreet, accessed July 2011.

24 http://www.gov.mb.ca/agriculture/ri/community/ria01s04.html.

25 Langdon community website http://www.goodlucktown.ca/, accessed December 2011.

26 B. Goodey, “The Healthy, Happy History Show: the Evolving Image of the Urban Heritage” in NSCAD Papers: Beyond Form, eds. Beverly A. Sandalack and Nick Webb (Halifax: Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1997).

27 An overview of population and dwelling counts by Statistics Canada comparing 2006 and 2011 indicates that many towns are experiencing population growth above the national mean.

28 Jack Stabler, Restructuring Rural Saskatchewan: Challenge of the 1990s (Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center, 1992).

29 Rural and Small Town Canada, ed. Ray D. Bollman (Toronto: Thompson Educational Publishing, 1992).

30 Government of Canada (2011) Census Canada.

31 Hough, Out of Place, 2.