’Tis but a game of mutual homicide,

Who have cast lots for the first death, and they

Have won with false dice – Who has been our Judas?

Lord Byron: Marino Faliero, Doge of Venice (1821)

Judas’ guilt-by-association in the Holocaust might – indeed, some would argue, should – have seen him pensioned off once and for all in the post-1945 era. What it certainly did cause was the outlawing of the ‘Judas the Jew’ stereotype from all but those most extreme fundamentalist Christian fringes where anti-Semitism continues unabated and unashamed. With such a large chapter in his poisonous past jettisoned, however, other readings of Judas’ story have been able to flourish. Now that he is no longer the resident scapegoat of institutional Christianity, or shorthand for anti-Semitism, Judas is enjoying a vivid old age. His name remains readily recognised, far beyond the confines of churchgoers, while, freed from the constraints of official doctrine or dogma, the known elements in his story are in a constant state of revision and reinvention.

Jorge Luis Borges, the Argentinian essayist and short story writer, published extensively before, during and after the Second World War. He highlighted in particular Germany’s ‘chaotic descent into darkness’, attacking the Nazis’ racist ideology, and their corruption of culture to inflame anti-Semitism. It is within this context that his enigmatic short story, ‘Three Versions of Judas’, appeared in 1944.1 Its structure is typical of Borges’ output, written as if it is a scholarly factual account of a writer and his oeuvre, but that writer is fictitious. The ‘deeply religious’ theologian, Nils Runeberg, lives in the Swedish city of Lund at the start of the twentieth century and tackles the gospel story of Judas ‘with a singular intellectual passion’,2 determined to make his academic reputation. In all, Runeberg pens not one but three attempts to explain Judas’ motivations, each reworking what he had previously proposed in an effort to win universal approval. It is, in Borges’ telling, a doomed task.

There has been, ever since the short story appeared, much debate about quite what Borges was saying. ‘Three Versions of Judas’ could just as easily be taken as an exposé of the pointlessness of biblical scholarship, seeking absolute truth from texts that, because of their nature, can never yield it, as it could an attack on the machinations and inventions of institutional religion itself, endlessly reshaping its holy books in an ultimately futile effort to make an impact, or to improve the human condition. Or it may be a reflection on how hard it is, given the available material, to arrive at a final, definitive version of Judas.

Runeberg’s first Judas is, pretty much of his time, not the devil-fuelled traitor of the medieval church, but the figure who had become increasingly popular since the Enlightenment. De Quincey is even name-checked. In handing over Jesus, Runeberg writes, the political revolutionary Judas might even be seen as a noble hero, keen to ‘set in motion a vast uprising against Rome’s yoke’. Of the betrayal, Runeberg describes it as ‘a predestined deed . . . which has its mysterious place in the economy of the redemption’.

This first version, too, represents the more contemporary theological view of Judas. This holds that since Jesus is the Son of God – as John puts it ‘the word was made flesh, he lived among us, and we saw his glory, the glory that is his as the only Son of the Father’3 – everything that happens to him on earth must be part of God’s plan. And so Judas’ betrayal is Runeberg’s ‘predestined deed’ – an integral part of that divine plan that will see Jesus rise from the dead and save humankind. That is why Jesus tells Judas after identifying him as the betrayer, ‘What you are going to do, do quickly.’4 Judas is playing his part, working from an already agreed script, doing God’s work, rather than the devil’s.

Borges then offers a second version of Judas. When Runeberg’s first theory is published in 1904, the short story tells, it is widely refuted, not just by the local ‘sharp-edged bishop’, but also by others who remain unconvinced. So Runeberg tries again, evolving his thinking now to see Judas as motivated by ‘an extravagant and even limitless asceticism’.

It is a portrait that has a touch of Gnosticism to it. This Judas ‘renounces honour, good, peace, the Kingdom of Heaven, as others, less heroically, renounced pleasure. With a terrible lucidity, he premeditated his offence . . . [he] sought hell [because he thought] happiness, like good, is a divine attribute and not to be usurped by men.’ So the choice to betray Jesus is his and his alone. He is not following God’s plan, but is using his own free will, albeit, as he would see it, to a divine purpose. He is not malicious or greedy, or any of the other negative qualities that had been attributed to him down the centuries. Instead he is sacrificing himself, knowing the consequences, realising that the promise of heaven is hollow, and that ‘happiness [is] not to be usurped by men’. This second Judas is a realist, or even a pessimist.

When this version again falls flat on publication, Runeberg puts forward his third and most radical alternative, arguing that if God really did choose to take human form, then he would have picked the vehicle of Judas, rather than Jesus, since Judas more completely reflected all that man was capable of – for good and for ill. There are hints here of the theory Robinson Jeffers had advanced in ‘Dear Judas’, of a Judas–Jesus role reversal. And as Jeffers had discovered, this third take on Jesus by Runeberg is regarded by his audience as blasphemous. He has failed to explain Judas convincingly and, as a consequence, is degraded. He becomes a lost soul, ‘intoxicated by insomnia’. He wanders the streets of Malmö, where he dies of an aneurysm. ‘To the concept of the son,’ Borges writes, ‘he added the complexities of evil and misfortune.’ As indeed Judas does by his role in the gospels. Borges is far too subtle a writer to provide a straightforward ‘answer’ to the questions he raises, in this enigmatic short story, but what it does demonstrate is both the allure of Judas, in terms of the challenge of trying to make sense of him, and, as Borges would have it, the inevitability of failure.

That warning, though, did not deter others. Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis presents another memorable Judas in his 1953 novel, The Last Temptation of Christ. It was condemned by the church in his homeland – something that once would have crushed a book and its writer, but which in the latter half of the twentieth century had the opposite effect, endearing the novel to a large, admiring international audience.

Kazantzakis has Judas and Jesus working together in doing God’s will, the former a red-bearded blacksmith once more cast as a Jewish zealot, who regards the Roman forces occupying his homeland as ‘criminals’. It is that political, nationalistic conviction that leads him to break with Jesus over his message of turning the other cheek. ‘Are we supposed’, Judas asks him, ‘to hold out our necks like you do your cheek, and say, “Dear brother, slaughter me, please”?’5 This is an earthy, real-world Judas.

Kazantzakis echoes the gospels’ portrait of an evil betrayer to the extent that Judas is literally two-faced, one aspect ‘sullen and full of malice’, the other ‘uneasy and sad’. Yet for all his very human mixed-up feelings about Jesus, Judas remains in this telling unmistakeably God’s agent, what Kazantzakis characterises as the ‘sheep dog’, who guides the sometimes vacillating Jesus to his planned sacrifice of himself for the sins of humankind. Sheep dogs are, of course, far removed from treachery. ‘We two must save the world’, Jesus tells Judas.

In what was to prove the most controversial section of Kazantzakis’ novel when it was adapted for the cinema in 1988 by Martin Scorsese, Jesus has a dream before his ordeal on the cross. Christianity teaches that Jesus is both fully human and fully divine. In the dream, Kazantzakis explores the tensions that this sets up within him. In his reverie, Jesus imagines what would happen if he rejected his divine destiny. He could marry Mary Magdalen. It was the scene of them consummating their bond that caused religious fundamentalists to boycott cinemas where the Scorsese film was shown. But the storm about their on-screen lovemaking obscured what was potentially an even bigger volte-face. In Kazantzakis’ reworking of the gospels, it is Judas (played in the film by Harvey Keitel) who is now no longer the traitor but the guardian of Christian orthodoxy. He brings Jesus sharply back to reality from his dream. And, as Jesus fondly imagines a reunion with his elderly apostles at the end of a long life, it is again Judas, standing by ‘a withered, lightning-charred tree’, who rebukes his master and accuses him of being a traitor. ‘Your place was on the cross. That’s where the God of Israel put you to fight.’

Judas’ role may change radically, but the essential story of Jesus’ sacrifice remains the same in Kazantzakis’ telling. Judas is not required to be an evil betrayer for Jesus to die and rise from the dead, but there is an alternative role he can play in casting light on the Christian story. The Last Temptation is, arguably, a novel about human frailty, Jesus’ as much as Judas’, and how our weaknesses potentially distance and distract us from God. In a century that had already witnessed two world wars, the Holocaust, and the dropping of atomic bombs on Japan, it had a particular resonance. As the most worldly of the twelve, and the most reviled, Judas provided Kazantzakis with powerful raw material to refashion.

And there is another intriguing reworking of Judas’ story in Shūsaku Endō’s deeply reverent 1966 novel, Silence. Like Kazantzakis and Graham Greene, with whom he has been regularly compared, Endō took religion as a central theme in his fiction and his life. Internationally admired, and said to have narrowly missed out on the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1994, he was one of Japan’s tiny Catholic community (fewer than 1 per cent of the population).

Silence has a historical setting and tells of a Portuguese Jesuit missionary priest, Sebastião Rodrigues, who comes in the seventeenth century to nurture the crop of Catholic converts struggling to grow in the hostile soil of Japan. The authorities do not welcome such missionaries, and so he is smuggled into the country by Kichijiro, a devout convert. His ‘face with its fearful eyes like a spider’,6 Kichijiro turns out to be Rodrigues’ Judas when he betrays him to the magistrate for a handful of coins.

So far, so straightforward, as a representation of Judas, but Endō then reimagines the Calvary narrative. The captured Rodrigues is forced by the Japanese authorities to watch as fellow Catholics are tortured and killed. He can save himself, they tell him, by the simple act of stamping on an image of Christ – called a fumie. In his distress, Rodrigues cries out to God to end the suffering he is witnessing, and to give him the courage to resist his tormentors, to be truly Christ-like.

‘Men are born into two categories,’ he records in his prison diary, ‘the strong and the weak, the saints and the commonplace, the heroes and those who respect them. In time of persecution the strong are burnt in the flames and drowned in the sea; but the weak, like Kichijiro, lead a vagabond life in the mountains. As for you (I now spoke to myself) which category do you belong to? Were it not for consciousness of your priesthood and your pride, perhaps you like Kichijiro would trample on the fumie.’

Kichijiro, Endō’s Judas, is then simply ‘weak’ in his faith. But what about Rodrigues, the Jesus-like figure? Real life, the novelist suggests, is much more complicated than goodies and baddies, the pure and corrupt. However straightforward such clear categories sound when reading the gospels, or living them out in ordinary times, they become unattainable when under duress. Rodrigues hears no voice of God to keep him on the path of the righteous. It is he, not Judas, who succumbs to despair. And it is he who betrays his Lord. Sensing the futility of martyrdom without knowing that God is on his side, he allows himself to be persuaded to recant.

As soon as he has done it, though (in another parallel with the Judas of the gospels), he regrets his actions. He is now no better than Kichijiro, he tells himself. He is Judas. That is how easy, he realises, it is to cross the line between good and evil.

In the final scene of the novel, Kichijiro comes to Rodrigues and asks him if he can hear him confessing his sins. As one who has renounced his priesthood by his denial of God, he is no longer allowed to do so, but Rodrigues reasons that to say no would be a failure to show Christ-like forgiveness to his betrayer. He shares his dilemma with the still-silent God. ‘But you told Judas to go away: “What thou dost, do quickly”. What happened to Judas?’

And, finally, Rodrigues gets his longed-for reply from God, but it is not the message he is expecting. God denies rejecting Judas. ‘I did not say that,’ the voice tells Rodrigues. ‘Just as I told you to step on the plaque [the fumie], so I told Judas to do what he was going to do.’ What Rodrigues has taken to be his own, and Judas’ betrayal, is nothing of the sort. It is God’s work, and it comes at a cost. ‘For Judas was in anguish,’ the voice says, ‘as you are now.’

Released from hell

If those outside clerical ranks, some devout, some not, were revisiting Judas’ betrayal in such powerful ways, what of the mainstream churches themselves in the post-war years? Was there any response to this growing chorus that suggested Judas had been done an injustice by all the blame heaped on him over the centuries?

Mostly, there has been silence on the subject of Judas. It is, in one sense, an improvement on noisily condemning him, and using his example to scapegoat others. And that silence may have been intended as a form of atonement for their sins over the centuries in promoting the image of ‘Judas the Jew’ with such appalling consequences. Even on those occasions when the twenty-two gospel passages in which he features come up in the rota of readings for mass, Judas is today generally overlooked as a topic for homilies, theological tracts, bishops’ letters or papal pronouncements. It is as if he is an embarrassing skeleton left over in the cupboard from an earlier age of intolerance. If no one mentions him . . .

On a more positive note, a transformation has taken place in relationships between Christianity and Judaism, reversing almost two millennia of hostility. There have been practical gestures – the removal in 1960 by Pope John XXIII of the reference to ‘perfidious Jews’ from Catholicism’s Good Friday liturgy. In medieval times, it had been followed by violent attacks on Jews and Jewish homes and businesses.

Five years later, as part of the landmark Second Vatican Council’s commitment to modernise the Catholic Church, the declaration Nostra Aetate was published by Pope Paul VI, formally acknowledging the close ties that bind Judaism and Christianity. It had been the early church’s anxiety to deny these, and so to separate itself from its own roots, that had fuelled the promotion of Judas as a scapegoat to damn all Jews. So, in that same spirit of atonement, almost 2,000 years after the event, Catholicism declared that the Jewish people bore no collective guilt for Jesus’ death.

Perhaps it should come as no surprise, given his toxic role in Christian anti-Semitism, that Nostra Aetate made no reference at all to Judas. Elsewhere, too, significant mentions by Christian leaders of Judas have been few and far between. When they do let his name slip, the connotation is still usually negative. In April 1971, for instance, when Pope Paul VI was giving a Maundy Thursday reflection lamenting the number of priests and nuns who had left the active ministry to get married as a result of the changes instigated by the Second Vatican Council, he chose to describe them as ‘Judases’. Re-reading the story of the treacherous apostle, he said, he had not been able to prevent himself thinking of ‘the escape of so many brothers in the priesthood’.7 It was a new entry to the list of wrongdoers – in the eyes of the church authorities, at least – whose ‘crimes’ could be bemoaned by scapegoating Judas.

With the dawn of the new millennium, however, there has been a small shift in attitudes within Catholicism towards Judas. Oberammergau, still going strong, commissioned a new script for a special staging of its passion play in the year 2000. Previously tough on Judas, albeit with some mitigation, the new version, in Act VII, features the ‘Despair of Judas’. The title may be impeccably medieval, but the words are not. The choir sings out: ‘See Judas fall into the darkness below. Why does no brother hold him tight? Gracious Lord grants mercy to the ostracised.’8 Judas is now presented as a reminder of God’s mercy towards the marginalised. That is another new role for him.

The impending publication – in National Geographic in 2006 – of the rediscovered Gospel of Judas gave added impetus to whatever slight revisionist tendencies existed in the upper echelons in Rome. Monsignor Walter Brandmüller, the German head of the Vatican’s Committee for Historical Science, was reported as having told fellow Bible scholars at the start of that year that he believed Judas was ripe for a re-reading. While the Gospel of Judas would contain ‘no new historical evidence’, he confidently (and accurately) predicted, it may yet ‘serve to reconstruct the events and the context of Christ’s teachings as they were seen by the early Christians’.9

Monsignor (later Cardinal) Brandmüller subsequently rejected as exaggerated reports that he was part of an official ‘campaign’ to rehabilitate Judas. He even dismissed the Gospel of Judas as ‘a sort of religious novel’, but that earlier intervention did at least prompt another Vatican insider, the Italian writer and senior layman Vittorio Messori (who had co-written a book with Pope John Paul II) to raise his voice too. Referring to Jesus’ observation in Matthew’s gospel that it would have been better if Judas hadn’t even been born, he said: ‘Jesus’ words about Judas are tough [but] Judas wasn’t guilty. He was necessary. Somebody had to betray Jesus. Judas was the victim of a design bigger than himself.’10

So Judas is no longer taboo in the Vatican, nor is he utterly reviled by all, but any talk of the authorities revisiting his case as a potential miscarriage of justice is premature. Pope Benedict XVI, John Paul’s successor, published in 2007 the first of the three-part exploration of the life of Christ that became the defining act of his papacy. The theologian-pope did offer a few more crumbs of comfort than his medieval predecessors might have done over the arguments traditionally deployed against Judas. ‘The light shed by Jesus into Judas’ soul was not completely extinguished. He does take a step toward conversion: “I have sinned”, he says to those who commissioned him. He tries to save Jesus, and he gives the money back. Everything pure and great that he had received from Jesus remained inscribed on his soul – he could not forget it.’11

That is as far as Benedict was prepared to go. He gave no ground to those who argued that Judas was God’s agent, doing what had already been decided for him. Instead, he returned to the favourite medieval image of ‘Judas desperatus’. ‘Now he [Judas] sees only himself and his darkness; he no longer sees the light of Jesus, which can illumine and overcome the darkness. He shows us the wrong type of remorse: the type that is unable to hope, that sees only its own darkness, the type that is destructive and in no way authentic.’12

If Benedict refused to be moved by the pleas to reconsider Judas’ role, the ‘Preacher of the Papal Household’ was. By tradition, the Good Friday sermon in Saint Peter’s is delivered by the Preacher of the Papal Household, always a Capuchin Franciscan Friar, and for the last thirty years Father Raniero Cantalamessa (his surname means ‘sings the mass’). His 2014 oration took as its theme, ‘Why did Judas become a traitor?’

The short, uncontroversial answer given by Father Cantalamessa was ‘love of money’. Then, however, he ventured into more contentious areas. ‘Judas began with taking money out of the common purse,’ he said, quoting John’s gospel. ‘Does this say anything to certain administrators of public funds?’13 This pointed question took the congregation back to the dawn of capitalism in medieval Italy, when Judas with his money-bag was used to scapegoat the emerging class of merchant-bankers. The church’s suspicion of the money economy has never wholly gone away.

Father Cantalamessa next went on to mention drugs barons, the Mafia, arms manufacturers and those who organise the sale of human organs as being potential beneficiaries of a careful reflection on the lessons of Judas’ example. And he had one more sensitive target. The false apostle, he argued, was recalled whenever ‘a minister of God is unfaithful to his state in life’.

This preacher had in previous years caused headlines by referring from the same pulpit to the scandal of child sex abuse by priests as, for too long, something swept under the carpet elsewhere in the Vatican. On this occasion, it was thought that his remark was likening Judas’ betrayal to that of paedophile priests.

Finally, he chose to pose a question that had been debated for 2,000 years – whether Judas was in hell. The gospels offer no definitive statement (on Judas, or anyone else who might be there), but it has long been taken as read by Christianity. Father Cantalamessa, though, stressed there was always the chance of repentance, right up to the very last minute, and said that he, for one, hoped therefore that Judas had taken up that offer in his final moments in Hakeldama.

That, of course, was the opposite of the impression Pope Benedict had given in his published remarks on Judas a few years earlier. While the disparity between the two can hardly be described as a major schism, it did at least give the topic an airing. Hell is another of those taboos in mainstream Christianity, generally considered too medieval and condemnatory to name check at a time when the emphasis is on a God of love. Even the devil is rarely mentioned. No Pope since Paul VI in the early 1970s has managed more than the odd fleeting reference to Satan.

Some Catholic traditionalists, however, refuse to collaborate in the silence, and line up instead with those Evangelical and Pentecostal churches which trumpet a literal reading of the gospels on the subject of the devil, and of hell. It exists, they assert, and contains the worst of sinners such as Judas. The conservative American Cardinal Avery Dulles, a distinguished Jesuit theologian, argued in an essay published just before his death in 2008 that the language of scripture about Judas ‘could hardly be true’ if he had been saved from damnation. He rejected any notion of an empty hell – i.e. one without Judas – as the ‘thoughtless optimism’ characteristic of the modern age.14 Some clerics still require Judas to be held up only as a cautionary example to believers.

The question of where Judas is spending eternity is not only of interest to cardinals and traditionalists. It also intrigued the American playwright, Stephen Adly Guirgis, though he came up with a very different answer. Raised Catholic, like Kazantzakis, Greene and Endō, he takes faith as one of his central themes, and is almost alone in Broadway, London’s theatre land and elsewhere in successfully mining the once ubiquitous, now almost forgotten, seam of religious drama, the modern-day inheritor of the mystery and passion play tradition. Adly Guirgis’ The Last Days of Judas opened in New York in 2005, following in the footsteps of his Our Lady of 121st Street and Jesus Hopped the ‘A’ Train, a parable set on Death Row. His urban argot may be expletive-ridden, but his purpose is serious.

In The Last Days of Judas, his chosen vehicle is an unusual courtroom drama, with an appeal being heard in purgatory from Judas, who is petitioning to be allowed out of hell. Among the various disreputable witnesses called are Judas’ traditional fellow inmates, Satan, Pontius Pilate and Caiaphas. Mary Magdalen pops up to share that Judas was ‘Jesus’ favourite, too . . . almost an alter ego to Jesus . . . the shadow to Jesus’ light’. But the court’s decision is not the real point. That is posed most directly by Judas’ widowed mother, here called Henrietta, as she recalls burying her son in the soil of Hakeldama after his suicide, with no one else willing to help her. ‘If my son is in hell,’ she wails, ‘there is no God.’

Adly Guirgis suggests that since there is no limit to God’s forgiveness (the gospels make the point repeatedly), then Judas too must be forgiven. The logic is hard to deny, but it is a conclusion some in the churches still resist. Judas, they say, remains a special case.

Burning bright

With formal religious attachment in steep decline in the West, and the teaching of the gospels now patchy in many schools, polls suggest many now are ignorant of the most basic details of the gospels. In the United Kingdom, a 2012 newspaper survey found that 21 per cent of those questioned were not able to say what happened on either Good Friday or Easter Sunday. ‘Something to do with rabbits’ was one response. And 23 per cent were not able to identify Jerusalem as the location for the events of the Easter story. Judas, though, continues to poll rather better. In the same survey, 55 per cent identified him as the betrayer of Christ.15 His name recognition – that most prized of twenty-first-century commodities – remains high.

And that is despite the fact that – within living memory – some age-old associations with his name have died out. In my hometown of Liverpool, a port city and therefore more international than most in the customs that have washed in with the ships, there was a ritual that survived well into the twentieth century in the streets of Dingle, in the south end of the city, close to the docks, of marking Good Friday morning by carrying round a Judas scarecrow door to door, collecting pennies. Then the cry would go up, ‘Burn Judas’, and a bonfire would be lit.16

It was something my mother’s generation could recall happening well into the 1930s, and there are police reports from 1954 of officers intervening to stop ‘Judas fires’ being started. ‘It is comic’, the records note, ‘to see a policeman with two or more Judases under his arm, striding off the Bridewell and 30 or 40 children crowding after him crying Judas!’ Another source claims a sighting as late as 1970.17

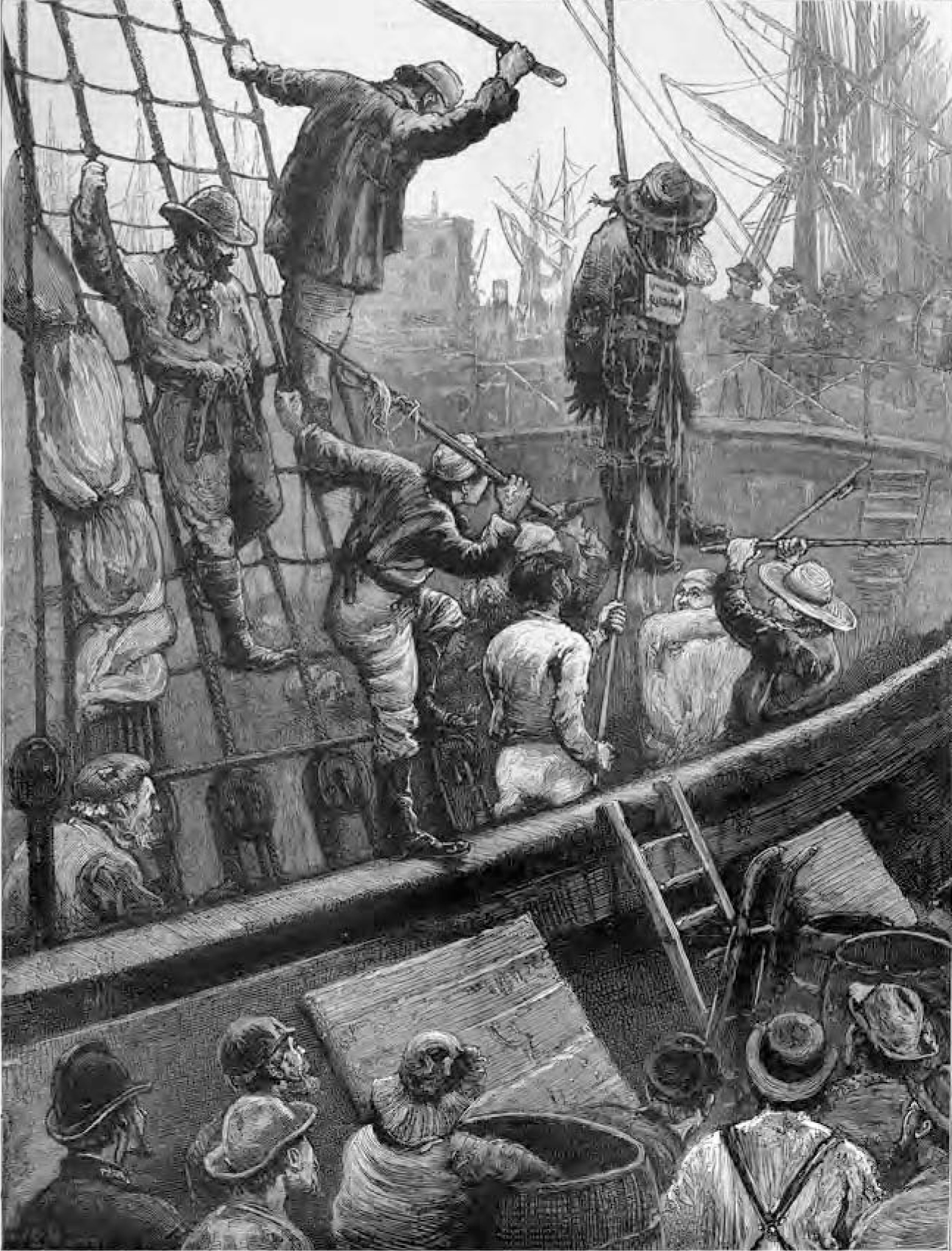

It shares most of the characteristics of the wider British habit on 5 November of first parading then burning a ‘guy’, representing Guy Fawkes, the Catholic conspirator whose Gunpowder Plot of 1605 was an attempt to blow up the Protestant monarch, James I, and the Houses of Parliament. And it is a short journey from Judas’ treachery to Guy Fawkes’. But the origins of this tradition in Liverpool seem to have been visiting sailors from Portugal, Spain, Greece, or even Latin America, landing in Liverpool over Easter and sharing their own customs. They had long been doing something very similar in other ports. An 1874 illustration from The Graphic and an 1884 report from The Times both describe Portuguese sailors flogging a Judas effigy on the deck of their ships in London docks on Good Friday,18 but by the early twentieth century such spectacles had ceased. Why it persisted longer in Liverpool is hard to know. The city’s heightened religious divide – with Catholic and Protestant populations at loggerheads well into the 1970s – may well provide some context.

‘Burn Judas’ was street theatre. Moving indoors to popular theatre, Judas gained another new lease of life in 1970 with Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice’s Jesus Christ Superstar, a musical so popular that star-laden revivals continue to this day. Its Judas is a composite of nineteenth- and twentieth-century interpretations that follow the structure of the gospel narrative but turn him once more into a misunderstood anti-hero. He is the rebel who feels let down when Jesus embarks on a divine rather than a political mission, but he is also in love with Jesus – he reprises ‘I Don’t Know How To Love Him’, Mary Magdalen’s ballad from earlier in the show. His insistence on following his own conscience, however mistaken he may be, casts him as victim, not villain, and leads to his lonely death by hanging from a tree, but it is mitigated when he rises to join in the final chorus.

Judas’ credits in recent decades could fill pages: from New Zealand literary novelist, C.K. Stead, and his 2006 My Name Was Judas, where the betrayer has survived into old age to reflect sceptically on Jesus’ claims to divinity,19 to the more populist Jeffrey Archer and his attempt the following year (co-authored with a senior Vatican advisor) to recreate Judas’ tale through the eyes of his son, Benjamin;20 from a transsexual Judas, now known as Judith, in Monty Python’s 1979 send-up of Jesus, Life of Brian, to Terrence McNally’s 1998 play, Corpus Christi, which shifts a gay Jesus and his all-gay apostles to Texas to face their persecutors. Though all base their characterisations to some degree on the gospels, and all reach very different conclusions, the proliferation of Judases, many of them controversial, some high profile, reveal an enduring quality about him – that his story is both compelling and capable of infinite adaptation. He dances to the music of time.

The Graphic reports on Portuguese sailors flogging a Judas effigy in London Docks on Good Friday (1884).