’Twas the body of Judas Iscariot

Lay in the Field of Blood;

’Twas the soul of Judas Iscariot

Beside the body stood.

Robert Buchanan: The Ballad of

Judas Iscariot (1874)

The signage in Jerusalem is, at best, intermittent. On the journey in from the airport at Tel Aviv, there are familiar, standard-issue, large roadside boards, with directions in three languages – Arabic, Hebrew and English. Once inside the Old City, with its Jewish, Muslim, Christian and Armenian quarters, it all gets much more hit and miss: odd arrows here and there, often with any wording obscured by a market vendor’s display of holy pictures, pottery or pyjamas, pointing variously to the Western Wall, holy of holies for Jews, or the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, standing on what is believed to be the site where Jesus was crucified, or the Al-Aqsa mosque, high on the list of must-see sites for Muslims. But never all three at once. Perhaps – to apply the most benign standards – it is assumed that in such a small space (within its ancient walls, the Old City of Jerusalem amounts to just under a square kilometre), visitors will inevitably stumble on this extraordinary trinity if they walk around for long enough.

In my wanderings, I only spy one sign for Hakeldama (originally the Aramaic hagel dema, sometimes rendered as the Greek Akeldama, and meaning ‘Field of Blood’), the spot where Christian tradition holds that one of the twelve apostles, Judas Iscariot, ignominiously committed suicide after betraying Jesus. And, even then, it is very much a forgotten footnote, down in the corner of a weather-beaten outdoor pilgrims’ map on display at the church of Saint Peter in Gallicantu, outside the Old City. Everywhere else is name-checked in big letters, with a rough drawing next to it. Hakeldama, though, floats on the margins of the map, as if halfway to oblivion.

If visitors did once seek out the scene of Judas’ last moments on earth, and there is plenty of historical evidence that pilgrims did, then it has now fallen from the itineraries of the estimated 3.5 million tourists who come to Jerusalem each year. Such modern neglect has a certain logic. Encouraging hordes to seek out the spot where Christianity’s most notorious traitor hanged himself would, in secular times, add a curious voyeuristic twist to 2,000 years of vilifying Judas, whom the gospels describe as partaking in the first-ever Eucharist at the Last Supper, but still managing afterwards to sell his master for a measly thirty pieces of silver.

That tawdry transaction was the first never-to-be-forgotten moment of infamy in the tale of Judas that has been handed down the centuries. In the core texts of Christianity, the second instalment comes soon afterwards when, in the Garden of Gethsemane, Judas identifies Jesus to a detachment of soldiers with the notorious ‘Judas kiss’. That embrace, outwardly of friendship but in reality of betrayal, has come to sum up the reputation of the traitor within Jesus’ trusted inner circle. And then, with Christianity for centuries confining Judas’ biography to a three-act drama, there is the concluding spectacle of the false apostle yielding to despair and killing himself.

What is there, then, to see at the Field of Blood, other than the ugliest side of human nature – and frankly there is enough of that to witness day to day in the grating tension between holiness and darkness in the divided city of Jerusalem? Judas’ place of death, moreover, offers no enticing prospect of the sort of spiritual nourishment that today draws even the most sceptical visitors to Jerusalem’s array of ‘holy places’. All of these sites may still cause endless, bitter disputes between the faiths. The golden-topped Dome of the Rock shrine, for example, alongside its near neighbour, the Al-Aqsa mosque, sits atop the Temple Mount, simultaneously hallowed ground in Judaism, and once commandeered by the invading Crusaders in the twelfth century for their own Christian church. Yet it still attracts crowds. We wait in long lines to pass through security points designed to filter out those fanatics with their guns and bombs who might be tempted to press by force their particular branch of religion’s claim. Once inside, though, whatever its bloody, factional past and present, this sacred ground still has the capacity to inspire.

By contrast, at Hakeldama, Judas’ last footprint on earth represents more of a cautionary tale, of the type once found in now-neglected children’s literature such as Struwwelpeter,1 and from which we adults are increasingly conditioned to recoil as too blunt, too black and white for modern sensibilities. Down the ages Judas has been singled out from innumerable other human options as absolutely the worst of the worst. In John’s gospel, he is damned not just as the devil incarnate but also as ‘the son of perdition’.2 Pope Leo the Great, in the fifth century, demonised Judas as ‘the wickedest man that ever lived’.3 Nine hundred years later, in the greatest poem of the Middle Ages, Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, he is sentenced to the ninth and final circle of hell, reserved for those who have committed the most heinous crimes of betrayal known to humankind, an eternal, icy torment shared with Brutus and Cassius, murderers of Julius Caesar, and, of course, Satan, from whose frozen mouth Judas dangles, half digested, his legs kicking in vain against his fate to the very end.4

And Judas Iscariot’s name continues in the twenty-first century to represent a crushing rebuke, a despicable traitor, as in the controversialist Lady Gaga’s 2011 single, ‘Judas’, about being in love with a bad ’un. ‘Jesus is my virtue’, she sings in a promotional video bursting with religious imagery, ‘and Judas is the demon I cling to’.

Yet, even for that contemporary minority with an overactive interest in the macabre – and there are plenty, I have observed, who like nothing better than ghoulishly to travel the globe seeking out ‘haunted’ places where horrific deeds took place5 – the Field of Blood scores poorly as a desirable destination. There are doubts, above all, about its authenticity.

Whose blood is it that is being remembered? That of Jesus, sacrificed on the cross on Calvary on Good Friday to save humankind, or of Judas, spilled in death following his betrayal of his master? In his gospel, Saint Matthew makes plain that it is Jesus’ blood.6 He writes bleakly and movingly (for this listener at least, when hearing the passage read aloud during mass over the years) of Judas’ wretched remorse once he had sold Jesus out. He tries to salve his conscience by returning his fee – the money paid to him for Jesus’ blood – but the chief priests refuse it as tainted. So, the outcast to trump all outcasts flings down the coins in the sanctuary of the Temple, takes himself off to an unnamed site and there commits suicide. The Jewish leaders thereafter pick up the sullied loot that is blood money for Jesus, and use it to purchase a plot, as a graveyard for foreigners, ‘called the Field of Blood’.

This account in Matthew does not place Judas’ suicide itself at Hakeldama. Indeed there is another tradition, albeit now muted, that suggests it took place within the Old City itself. So popular was it in its time that twelfth-century pilgrims would trudge along to visit the Vicus Arcus Judae (Street of the Arch of Judas), when the Christian Crusaders were running the city. One of the senior church leaders of that time, Archbishop William of Tyre, writes of Jerusalem, the city where he was born: ‘By the covered street, you go through the Latin Exchange to a street called the Street of the Arch of Judas . . . because they say Judas hanged himself there upon a stone arch.’7 On maps of the period, X marks the spot.

By contrast, in the Acts of the Apostles, coming after the gospels in the running order of the New Testament, the blood staining the Field of Blood is not that of Jesus but Judas.8 Moreover, Acts talks not of a suicide but of Judas dying by a kind of spontaneous combustion of his body that will find no name in medical dictionaries. Saint Peter, busy stamping his authority as Jesus’ anointed first leader of his fledgling church, describes, with the relish of the righteous, how Judas, his one-time fellow apostle, spent his ill-gotten silver pieces on purchasing the field himself, where ‘he fell headlong and burst open, and all his entrails poured out’. It was as if Judas had been struck down by a thunderbolt that split him in two. When news spread of this gruesome death, Peter continues, ‘the field came to be called the Bloody Acre, in their language Hakeldama’.

To thicken this historical mist, the precise site of Hakeldama is itself only a matter of tradition, rather than archaeological fact. It stands on a barren hillside on the south side of the valley of Hinnom, perched precariously in one of the cat’s cradle of stringy ravines that intersect the peaks and troughs of Jerusalem, but this location was simply the one chosen by the early Christians. In the centuries immediately following Jesus’ death, they picked out places in and around Jerusalem to associate with events described in the gospels, some on the basis of more compelling evidence than others. Their habit of praying at such sites was then taken up with gusto from the third century onwards by a new flood of pilgrims who came to the city with the specific intent of walking in the footsteps of their Lord.

On these itineraries, Hakeldama featured as the very spot where Judas lowered himself into the fires of hell with the jerk of a rope round his neck. One of the earliest references comes in Onomasticon, a study of place names found in Holy Scripture, compiled by Eusebius, Bishop of Caesarea in Palestine in the 330s, and one of the most hallowed of the early church historians.9 He refers on several occasions to the pilgrim site at the Field of Blood, and places it in the valley of Hinnom, south of Mount Zion (save on one occasion, when he unaccountably moves it north of the same peak).

Eusebius’ survey follows the bountiful visit to Jerusalem in 326 of Helena, mother of Constantine the Great, the Roman Emperor who in 313 had granted liberty to Christianity after centuries of persecution. A zealous Christian convert (and, by some accounts, a former barmaid who wasn’t married to Constantine’s father), the Empress Helena came to the city with her son’s blessing, and his permission to build monuments to her faith. Principal among the works she commissioned was the Church of the Holy Sepulchre itself, where it is said she had found the remains of the ‘true cross’ on which Jesus had been crucified. Among her other projects, though, was a new cemetery chapel on the hillside of the Field of Blood. It marked what had, since Jesus’ time, been a catacomb for the Christian dead. (This claim has some authenticity. A shroud has been found at Hakeldama still bearing clumps of human hair, dated as first century CE.)

It was not just Judas’ reputation that drew these diligent, pious early church pilgrims. It was on this same spot, in the niches carved out of the rock face of Hakeldama, that the apostles were said to have hidden away once Jesus was arrested and until his resurrection. Unlike Judas’ connection to Hakeldama, this claim has no basis whatsoever in the gospels, yet still became part of the tradition that developed in these first centuries of the church. Later the Crusaders, arriving at the end of the eleventh century on papal instructions to conquer Jerusalem on behalf of Christians, were to replace Helena’s cemetery chapel with a much larger structure, presumably because their arrival caused so many deaths and the foreigners’ graveyard was much in demand.

So, unsignposted though it may be today, people did once head in numbers for Hakeldama – to bury and remember the dead, to follow the trail of the apostles, and to recall Judas. It was the last of these three, its link to Jesus’ betrayer, that seems to have exerted the greatest pull. In the earliest surviving account of a Christian pilgrimage to Jerusalem, the Itinerary of the anonymous ‘Pilgrim of Bordeaux’ who came in 333, the author makes reference to ‘returning to the city from Aceldama’, having seen ‘in a dark corner an iron chain with which the unhappy Judas hanged himself’.10

The chain seems to be his own embellishment on Matthew’s gospel, which makes no mention of any such thing. It is by no means the first addition, and certainly is not the last. In the 680s, the French bishop Arculf made his own contribution. In De locis sanctis (‘Concerning Sacred Places’), his account of a journey to the Holy Land, he reports with some excitement going to Hakeldama and seeing the very fig tree from which the traitor was found hanging.11 The fig, by tradition the tree of life, was being crudely imported into the story of an inglorious death to amplify the significance of Judas’ story in the Christian narrative. And it has been talked up ever since. There, but for the grace of God . . .

‘You’re very lucky,’ pronounces the short, stout, balaclava’d Greek Orthodox nun who peers out round the half-opened red metal front gate of Saint Onouphrius’ Monastery. Since the 1890s it has been the only lived-in structure on Hakeldama, a small, fortress-like compound, clinging to the rock face and surrounded by high walls. They are topped by barbed wire, above which peep the branches of trees. Perhaps the fig tree that Arculf saw is still in bloom? Or, better still – and now my imagination is racing away – a Judas Tree, the pink-flowering Cercis siliquastrum, which reputedly got its name because, in other embellished accounts, its branches once played host to Judas’ rope?

‘We’re closed,’ says the nun, with a short-sighted smile, ‘but I’ll let you in.’ The notice board outside specifies the monastery’s brief, weekly opening hours, including this particular morning and this precise time, but it feels rude to point this out as she hospitably swings the door open wide. She had been showing out some workmen who had been helping her in the monastery gardens, she explains, when she spotted me making my way up the unmarked muddy track that leads to the monastery from the main road on the valley floor. Otherwise, she implies, the bell would have gone unanswered and made my pilgrimage fruitless.

Perhaps this absence of welcome – in marked contrast to every other site I visit in Jerusalem – is another reason for the decline in numbers heading for Hakeldama. We step into a wide, glazed porch area, with large picture windows looking out northwards towards the Old City, and the white, marbled steps made up of gravestones in the Jewish cemetery as they climb up the slopes of the Mount of Olives. Around us are a couple of dusty plastic tables with cellophane-wrapped floral covers, which might once have belonged in a café, long since abandoned. In one corner stands a small, crudely constructed piety stall with sachets of dried herbs for sale, plus booklets and prayer cards about Saint Onouphrius, a fourth-century hermit monk believed to be buried here. But, curiously, not so much as a passing reference to Judas.

The nun – who doesn’t tell me her name – wonders aloud what I am doing there. ‘No one much comes any more,’ she continues, almost to herself. Her English is perfect, and she has pulled down the flap of her balaclava sufficiently so that her words are not swallowed by the wool, but I still can’t detect whether it is relief or regret in her voice. There are, she reveals guilelessly, only two sisters living in the monastery now (a third died recently) and – here she gestures to the walled garden behind her, visible through an open gate – it is all getting too much for her. A pile of pruned olive tree branches and ripped-up geranium stalks lies by the entrance, waiting to be removed.

I’m starting to wonder if I have come to the wrong place and eventually find a gap in her monologue to slip in Judas’ name. There’s an immediate pause, and then the nun sighs impatiently. The flap goes back up over her mouth. ‘You are welcome to look round,’ she says, suddenly weary, ‘but the garden is private.’ She turns to retreat into it. ‘Is there a particular place in the monastery where Judas’ death is marked?’ My question is addressed to her back. I’m choosing my words as neutrally as I can, but a part of me is hoping that she will point to a tree.

Why suddenly so literal? Reason seems temporarily to have given way in me to what, with hindsight, I diagnose as a mild case of Jerusalem Syndrome, apparently a widespread affliction that sidetracks otherwise rational visitors to this city into religious fervour and a to-the-letter take on various holy books.12 Elsewhere, for example, I have watched myself dutifully bobbing up and down to touch outcrops of otherwise unremarkable rock where various events in Jesus’ life are said to have taken place. It’s given me a taste for the literal. There must be some remnant of 2,000 years ago here, too, surely?

The nun turns and shakes her head pityingly, as if spotting my malady before I do. ‘Our chapel is through there.’ She points to an arch at the other end of the porch and then she really does disappear through the garden gate, closing it firmly behind her, leaving me all alone in this peculiar place, where visitors no longer come, and Judas is he-who-must-not-be-named.

I hadn’t exactly been expecting an all-singing, all-dancing celebration of his life – the sort of dramatic re-enactment pumped out by a humming overhead projector onto a video screen that has become de rigueur in historic houses nowadays. But it had seemed reasonable, in planning this visit, and given the long – though admittedly thinning – historical trail of pilgrims coming to the spot, to hope for some sort of surviving discreet memorial: a plaque, perhaps, to mark the supposed place of Judas’ death, with solemn words and an unspoken warning not to follow in the traitor’s footsteps; or else a prayer card on offer, or an invitation to light a candle, as an opening onto a deeper reflection upon his story, and the still-unresolved questions it poses. Whether, for example, to abhor Judas, in line with the church’s traditional and lurid blanket condemnation of him as Satan’s tool, or to be swayed by the gentle recasting of his role as God’s agent that has gone on in recent times.

In 1963, well before he so publicly embraced Jesus, Bob Dylan wrote a song called ‘With God On Our Side’ that challenged America’s claim that its actions, especially in going to war, were somehow divinely-inspired. Dylan also included a verse that touched on the modern re-evaluation of Judas where he asked whether Jesus’ betrayer might also be judged as having had God on his side when he planted his traitor’s kiss.

Out-and-out traitor or cog-in-the-wheel of a divine plan? The same question, albeit without musical accompaniment, was posed in 2006 by a senior Vatican official, Monsignor Walter Brandmuller, head of the Pontifical Committee for Historical Science.14

Plain and white on the outside, save for the trademark onion dome of Greek Orthodox churches, inside the monastery’s chapel is small, cluttered and low-ceilinged, with stalactites of hanging lamps dividing up the space that is mostly burrowed out of the rock face behind. Its primary purpose, it quickly becomes apparent when I manage in the gloaming to locate the light switch, is to honour the obscure Saint Onouphrius.

Christianity has a long track record of playing fast and loose with its own history, covering up episodes it would rather forget with a sugar coating of legend. So ancient pagan water shrines, for example, were, in the early church, redesignated as ‘holy wells’ and assigned to a suitably devout and often manufactured Christian saint. In Jerusalem, this form of victor’s justice, burying the past and substituting a new one, is more marked than anywhere else I have ever come across. Layers of story, from whichever faith group was then controlling the city, are superseded by new layers, put down by new rulers, from a different faith tradition, once they wrest control. And on and on as Jerusalem has passed back and forth through the hands of Jews, Christians and Muslims to this day. Yet, probably because of all the competing claims to the ownership of the place that exist, now and apparently always, this is also a city where the surface layer of history is notoriously thin, allowing previous authorised versions to leak through.

Here at Hakeldama, the current top layer is a historically tenuous connection with a fourth-century hermit. Very little is known about Onouphrius, but even within these crumbs there is no real link to Jerusalem. No wonder so few people come to visit. So why has it happened? Why has the cult of an obscure saint been written so large as to all but obliterate the shadow that Judas’ corpse, hanging on the end of a rope, casts over his ‘bloody acre’?

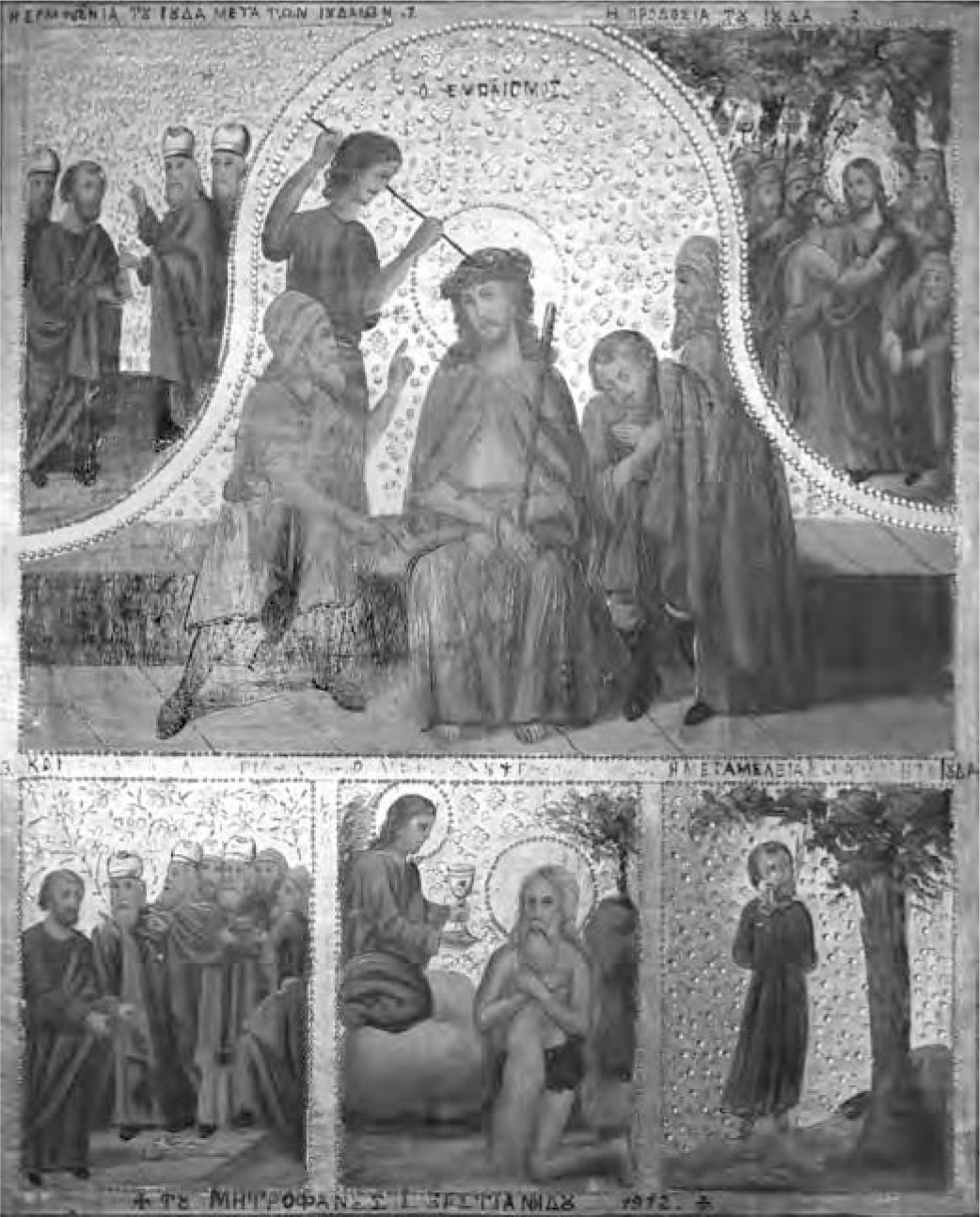

I’m still puzzling over that one when a previous layer peeps through. As I search in the darkened corners of the chapel, I come across a single, dusty icon, dated 1912, hidden behind an Ovaltine-coloured marble plinth. It makes a crude but revealing attempt to weave Onouphrius into Judas’ traitorous tale. The richly decorated panel, in greens, reds and blues against a gold background, features most obviously the risen Christ in the centre, the blood still flowing crimson from the wounds made by the crown of thorns on his head. Around this dominant figure, though, is arranged a series of small vignettes, telling in chronological order those three best-known gospel episodes in Judas’ journey to this very place. Plus an extra two.

The Judas icon in the chapel of Saint Onouphrius’ Monastery at Hakeldama in Jerusalem.

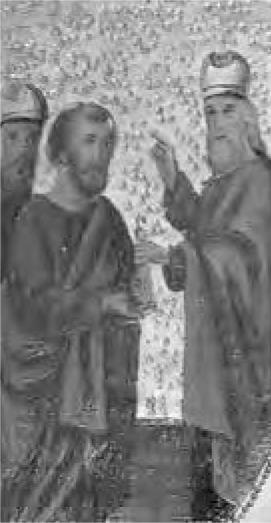

It kicks off in the top left corner with Judas being rewarded for betraying Jesus to them by the Jewish chief priests with a swag bag, marked with the number thirty in red, in case there is any room for doubt as to what it contains. Judas’ countenance is monk-like behind his beard, but otherwise inscrutable, neither villainously licking his lips at the prospect of spending his ill-gotten gains, nor troubled by selling out his leader so cheaply. The conventions of icon painting, favouring flat, two-dimensional, slightly featureless faces, rule out any strong hints as to the emotional or psychological temperature, but there is one visual clue. Judas’ hair has a copperish hue, the artist picking up on a long tradition in Christianity of portraying him as a red-head which, according to medieval writers, was the sure sign of a moral degenerate. Shakespeare, in As You Like It, likens Orlando’s hair to Judas’ red mop, describing it as ‘the dissembling colour’ and one that reveals ‘a deceiver from head to toe’.

Moving over, in the top right-hand corner, is the Judas kiss by which he identified his master to the soldiers in the Garden of Gethsemane. Judas is much shorter than Jesus, as if to emphasise his moral inferiority. His upturned face now carries with it just a touch of malevolence. He purses his lips as he reaches towards the impassive, saintly face of God’s Son to land his kiss, but there is no physical contact.

Back in the bottom left is the first addition – the remorseful scene from Matthew’s gospel that is usually overlooked in the standard three-act account of Judas’ place in Christian history.15 Here, an emotionless Judas attempts to hand back to the Jewish authorities the thirty pieces of silver, but fails, leaving the coins scattered on the floor. Before moving on to Judas’ demise in the final corner, however, the icon painter, from nowhere, conjures an image of a heavenly angel giving the bread of the Eucharist to Saint Onouphrius, immediately recognisable from the other representations around the chapel by his Rapunzel-length white beard, and simple loincloth of leaves, as befitting a hermit monk living in the wilds of the Egyptian desert.

The artist’s intention seems to be to substitute an image of the monastery’s patron saint receiving the communion bread instead of Judas. In three of the four gospel accounts, Judas is named as attending the Last Supper, where Jesus breaks bread and drinks wine, describes it as his body and blood, and so inaugurates what remains the central sacrament of the Christian Church.16 Theologians have long been troubled by Jesus’ willingness to allow Judas to be there at this key event for the future life of his church. This is, after all, an apostle who he knows is about to betray him. So here that unease is clumsily sidestepped by painting out Judas and inserting Onouphrius.

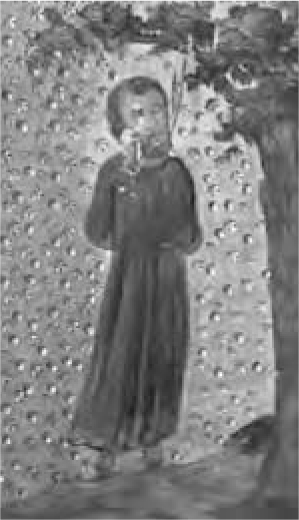

The story can then move seamlessly back on track for its usual conclusion: the death of Judas, hanging by a rope from a branch. His robe is now green to match the foliage – compared to the blue or yellow of earlier – and his eyes are shut. His face is suffused – I cannot help thinking – with a kind of peace; certainly not agony, though potentially a wish to be forgotten. He doesn’t look like a man expecting hell, the eternal fate Christian tradition has given him,17 in the company of his seducer, the devil.

If it is oblivion Judas is seeking, however, then here at Hakeldama his wish has been granted. The backdrop to this concluding scene is blank. There is no representation of Hakeldama; not even a hint of a hill, a garden or the Jerusalem skyline. The place of the betrayer’s lonely demise has been moved to no man’s land – out of sight, out of mind.

Behind the icon are various openings in the rock, their entrances secured with iron grilles. These are, according to Christian legend, the caves where the terrified apostles hid after Jesus had been arrested. The gospels recount how only Peter (and, in John’s gospel, an unnamed disciple who knows the high priest18) follow their leader as he stands trial, and how only the women among the disciples pray at the foot of the cross as their Lord expires. The others were cowering here, scared that the soldiers would soon come for them. They only emerged after Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection.

The association is yet another piece of imprecise geography, inherited from the early church, but it offers, nevertheless, an intriguing prospect. If it is to be believed, in one part of Hakeldama, one of the twelve apostles was swinging dead at the end of a rope, while in another, his erstwhile companions were in hiding. Did they hear him cry out as the rope tightened and do nothing? Or did he die silently, such was his overwhelming sense of shame? Was it only when they summoned the courage to emerge from hiding that they discovered his body? Did they bury it? Or feel regret? Or just step over it – the bad apple getting what he ‘deserved’?

I pause on leaving the chapel for a moment before deciding to brave it and give the recalcitrant nun-custodian one more try. Standing by the pile of branches and geranium stems, I call through the closed gate. ‘Sister?’ There’s no reply for a long time, though I can hear the telltale rustling of a busy gardener. In contrast to the barren hillside all around the monastery, what I can discern through the grille is a patch of colour, shade and life that roughly equates to the pairidaeza, the verdant walled garden in an otherwise arid place, of the ancient kings of Persia, which gave us the word paradise.

‘Sister,’ I try again. And again, the note of apology less pronounced each time. Eventually the sound of leaves shaking and plants being pruned stops. I hear footsteps coming towards me. The nun reappears at the gate. ‘I’m busy,’ she says with little grace. Honesty being the best approach, as the benign nuns of my Catholic childhood once taught me, I explain about my interest in Judas, that I’m writing a biography of him, hence my visit to Hakeldama. And I ask about the icon in the chapel.

Her reply is a shrug, as if to say, ‘It is what it is.’ Then she softens a little. She steps back into the entrance porch and reaches up to put her hand on a curious D-shaped stone that is plastered into the wall of the porch. I hadn’t noticed it when I first came in, but why would I? It is the same pale, sandy colour as all the others around it. The only thing that makes it stand out is its mildly irregular shape. ‘Some people have said that this is the rock where he died,’ she offers. ‘What sort of people?’ ‘Archaeologists who have come here.’ So there are still visitors in search of Judas. I wonder how she greeted them?

I am trying to reconcile a stone with the traditional image of a tree. Then it occurs to me that there is also Saint Peter’s account in the Acts of the Apostles, where Judas’ innards spill out. Onto this rock? ‘I suppose so,’ the nun replies. She looks sceptical. As well she might. It is not name-checked in the gospels, but then Jerusalem is full of similar rocks that I have been busy kneeling down to touch reverently. They, though, are surrounded by ornate marble frames, or found in the centre of the floor of great basilicas. Here the physical connection with the past has apparently been deliberately lost at shoulder height in a structural wall. It feels too aggressive to point that out. Instead I stretch my hand up and place it there for a few seconds. The nun looks on, unmoved.

The section in the Acts of the Apostles about Judas and his grisly end at Hakeldama is followed by a quotation from the Old Testament Book of Psalms. The whole of the New Testament is littered with references back to the Jewish Scriptures, the first Christian writers summoning up the past, its promises and prophecies, in an effort to make sense of Jesus’ life, death and resurrection. ‘Let his camp be reduced to ruin, let there be no one to live in it.’19 A prophecy of Judas’ death and final resting place? That is a stretch. But as a description of the rocky, barren, bare hillside of Hakeldama, and the absence of welcome that awaits contemporary visitors here, it couldn’t be more accurate.

I’m shown out of the monastery. Bundled out might be more accurate. The clang of the door behind me signals how anxious my host was to put an end to the awkward questions about any traces of the traitor her monastery obscures.

It has been raining over the previous days and the track back down to the busy road below is thick with mud; the sort of reddish, viscous clay that endorses Matthew’s talk of the ‘Field of Blood’ once having been a potter’s field, its soil useless for agriculture or grazing, but a source of raw material for potters. On the way down, placing my feet carefully so as not to slip, I spot small white and blue markings, painted onto a rock, and an arrow pointing the way up another path that doubles back through the boulders to the ridge above the monastery. They are the same colour as the Greek flag I have just seen flying inside the monastery, and I decide on no basis in particular that they may therefore be a clue that Orthodox pilgrims do, contrary to all indications, actually still come here, even go in procession.

I start to follow them, picking my way over cans, plastic containers, shopping bags, even a discarded garden chair. Then the markers peter out. Hakeldama hasn’t been taking new burials for over 150 years, but still I find myself in a charnel ground of modern debris. The contrast between the crowds and bustle of the Old City of Jerusalem – visible on the horizon, apparently so close I could almost reach out and touch it – and this desolate, abandoned place couldn’t be plainer. It is a desert cheek-by-jowl with the city, and in all religious mythology the desert is where the evil spirits reside; where, in the gospels, the devil preys on Jesus during his forty days in the wilderness.20

Up on the ridge above the monastery, there is, I discover, no hoped-for peephole into its closed-off garden. Instead, what looms suddenly large, having been invisible from the road, is the ruined stone arch of the Crusader chapel, almost buried in the hillside. A steep pathway curls round and down into it, but reveals only another rubbish dump. The catacomb burial niches, cut into the rock behind, are visible, but inaccessible without clambering through the contents of Jerusalem’s bins.

From the top of Hakeldama, I look out. The valley below is today called (and signposted) Hinnom, but is also known by its Old Testament name of Gehenna, the place where apostates sacrificed their children to gods by burning them alive.21 It was regarded as cursed then, and conflated with an earthly hell. The same connotations are taken up in the New Testament, in the Talmud of Judaism, and in the Qur’an, where the word for hell – jahannam – is derived from Gehenna. And this is still the bleakest of all bleak places, as suitable as Dante’s final layer of hell for a last, damning glimpse of the greatest of all sinners. So suitable, indeed, that Matthew, the only one of the gospel writers to describe the treacherous apostle’s death, may just have been reaching back into his memory for the name of the worst location he knew and making it the site of Judas’ last minutes on earth.

It’s speculation, but that has long been what has happened with Judas’ story because, striking as it is in the gospel accounts, it also remains frustratingly incomplete, leaving much unsaid, gaps begging to be filled. And fill them we certainly have, with 2,000 years of embellishment, straining for effect, stereotypes and symbolism tailored to the concerns of each particular age. Even here at Hakeldama, where archaeology rubs up against the detail of the gospels, there can, I realise, be no such thing as certainty.

This godforsaken landscape has highlighted, too, one of the key challenges in embarking on a biography of Judas Iscariot. Every detail of his story is capable of being looked at from a dizzying array of perspectives, through any number of historical lenses and prejudices. The questions that arise – who is telling his story, what precisely are they saying, and why are they doing it? – are, of course, the same as arise in writing any conventional biography, but in the case of Judas, each aspect of his story has already been stretched and strained, through century after century of contexts, most recently with the much-hyped publication in 2006 of the rediscovered Gospel of Judas.22

And yet, the memory of Judas, once marked here but now all but discarded in this valley of death and debris, lives on. It is not finished with, like the rubbish on the ground around me, nor is it part of the flotsam and jetsam of religious history no longer required in our shiny new secular, scientific and sceptical age. Even those who would struggle to arrange the basic events of Jesus’ life in any sort of order recognise Judas’ name, and may even deploy it occasionally as a term of abuse. It is being constantly recycled as the worst of insults, ‘the most hated name in human history’, as Bob Dylan put it recently, returning to a character who clearly still fascinates him.23 And while we continue so readily to scapegoat those who cross us, or take a path we disapprove of, or express an opinion that we find threatening, then the most basic story of Judas, arguably the biggest scapegoat in human history, is being repeated time and again.