Chapter 14

When the jury filed in the next morning, the old man offered them a big good-morning smile, which to me seemed as improper as it had the previous day. This time the first alternate nodded, and his eyes, at least, seemed to smile.

Ken Kobre resumed the stand for an hour. The old man spent a few minutes having him explain that the photographs of Joe Fagone finding the Fabrique Nationale were taken in front of 26 Smith Street “about halfway down the street” from the crashed Buick. Then he asked him to look at one of the pictures and read the “number plate of the Buick Electra.”

“I can make out F6•838,” said Kobre.

“Four-F•6838,” said the old man.

He passed the stack of photographs to the foreman and watched as the jurors eagerly examined each photograph.

The jury’s study of the photographs took fifteen minutes, during which, at Skinner’s invitation, Keefe began cross-examination. When Skinner noticed that none of the jurors was paying attention to Keefe, he told him to “wait until the jury is through.”

Once Keefe’s cross did get going, we were charmed by its timidity. Here was our second-most important witness on the stand. The time had come for the defense to show some spirit. We thought Keefe would surely take a run at Kobre’s “between three and five seconds.” After all, that time estimate was the most powerful contradiction of what would be the defense’s account of the shooting. But, presumably having decided that Kobre was too surefooted a witness, Keefe stayed away from the shooting itself. Instead, he concentrated on Kobre’s “conversations with the officers” and his memory of the radio traffic. It was all rehash, but it elicited an extra detail here and there that was helpful to us. For example:

KEEFE: Did you hear any calls while you were with Molloy and Dwyer?

KOBRE: Yes.

KEEFE: Can you recall what the call said?

KOBRE: That there was a robbery in Cambridge; that there were two men involved; that the men were thin . . .

Kobre’s testimony about no shouting at Bowden, no racing engines, no screeching tires, and the three-to-five seconds remained unchallenged when he stepped down from the witness stand.

The old man turned to the marshal and, with the verve of a Las Vegas announcer introducing Frank Sinatra, said, “David O’Brian, please.”

The hospital witnesses had to wait, because we wanted to have Kobre and O’Brian testify consecutively.

O’Brian entered, found his way to the witness stand, took the oath, and sat down. He adjusted the microphone downward to his own chin level and answered the old man’s questions, beginning with his employment history and leading to January 29, 1975.

“I was assigned to spend the afternoon and evening riding with members of the Anti-Crime Unit of the Tactical Patrol Force,” he told the jury in his careful, unassuming way. “I had a photographer with me—Ken Kobre.”

“The car I was first in was a car operated by Billy Dwyer and Mark Molloy. . . . At some point that afternoon we were transferred to another car with Officers Dennis McKenna and Edward Holland.”

Officer Holland “was carrying a clipboard, and he was using it to write down information that was coming over the police radio all afternoon.”

“A little before six, we had taken a turn down Smith Street into the Mission Hill project, and Officer Holland, who was in the passenger seat, recognized the license plate on a Buick . . . as a license plate that he had heard come over the police radio that afternoon [and] had been reported involved in a robbery in Cambridge. So we stopped, made a U-turn, and went back [to] Gurney Street within view of the Buick.”

“By the time we were on Gurney Street [with] the Buick under surveillance, it had started to rain. . . . It was already pretty dark, and there were no streetlights that I remember right on Smith Street. So, Smith Street was very dark.”

“Officer Holland had a walkie-talkie, and he was radioing to the other cars, two other cars also involved in this stakeout. . . . I heard Dwyer’s [voice].”

“We heard a report over the police radio that a shotgun had been used in the Cambridge robbery, and there was some conversation and some concern on all our parts about what was likely to happen if we were confronted with someone carrying a shotgun. . . . Officer McKenna advised Ken Kobre and myself that if any shooting occurred, we were to get down on the floor.”

“I was very frightened.”

“A dark-colored Thunderbird came around the corner. . . . it was six-thirty, six-thirty-five or so. . . . It came up Parker Street and took a right turn onto Smith Street and stopped parallel to the Buick. And a figure got out of the passenger side of the Thunderbird and walked over and entered the Buick on the driver’s side. . . . Officer McKenna started the car, and we began to go across Parker Street onto Smith Street . . . moving fairly slowly. . . . Officer Holland radioed to the other cars, ‘We’re going in. We’re going in.’”

“The operator of the Buick had started the car and had put it in reverse and was backing up in our direction. . . . The car I was in came to an abrupt stop. . . . We were almost on top of [the Buick].”

“The two officers jumped out of the car. . . . They were carrying handguns.”

The doors “were opened.”

“At that point, I dove to the floor. I didn’t see anything more.”

“After a period of a few seconds—from three to five seconds—I heard a series of gunshots. . . . They were rapid fire. Seven or eight.”

“I didn’t . . . hear Officer McKenna’s or Officer Holland’s voice . . . [or] any screeching tires.”

“After I heard the shooting, there may have been another—I don’t know—thirty seconds or so, and Officer Holland was the first to return to the car. . . . I remember him calling for help and saying that there had been a shooting. The only specific thing I remember hearing him say was: ‘No ACU injured.’”

“At that point, they drove the car . . . further down Smith Street to . . . where the Buick . . . had apparently collided with this utility pole and was up against . . . a chain link fence [in front of] the Tobin School.”

“I got out of the car . . . The first thing I saw was Officer McKenna approach the Buick. He was . . . reaching . . . through the window on the driver’s side, and he appeared to be holding the man behind the wheel.”

“Dwyer and Molloy . . . appeared on the scene, and a series of other police officers, who I did not recognize, came onto the scene very shortly.”

“No, I didn’t [speak to Officer Holland], although I did see him walking around.”

“Yes, I did [speak to Officer McKenna].”

“After I had seen him reach into the Buick . . . I noticed there was blood on his right sleeve, and I asked him if he had been hit in the gunfire. And he responded, ‘No, it’s his blood.’ . . . And then he said, ‘As soon as he turned the wheel, I said, ‘Fuck him.’ And he made a gesture with his hands indicating to me that that was when he opened fire.”

“At least five police officers [searched the Buick for] anywhere from a half to three quarters of an hour.”

Eventually, a “gun was found under the right front fender of a car that was parked . . . on the even side of Smith Street. . . . It wasn’t . . . in the vicinity of where the Buick crashed.”

The old man had O’Brian step over to the model. He pulled out his fancy pointer, which Skinner had taken to calling “that collapsible wand,” handed it to O’Brian, and asked him to show the jury where the Buick was originally parked, where it finally crashed, and where the gun was found. O’Brian complied, then resumed the witness stand.

Only one O’Brian item that we tried to get in was stopped by a defense objection. At the old man’s request, O’Brian began to recount Dwyer’s post-shooting remarks: “Officer Dwyer said to me—”

“Objection, Your Honor,” said Keefe.

“That is awful slow,” said Skinner, shaking his head, “after the answer is started. The objection is sustained.”

It was classic hearsay. Generally, witnesses are allowed to quote only what plaintiffs or defendants have said to them, not what anyone else—no matter how involved—has told them. With Dwyer on the stand, however, the old man could, on cross-examination, hold up the Kobre picture of Dwyer laughing and ask, “When that picture was taken, did you say to Dave O’Brian, ‘How’s this for action? Did we put on a good show for you?’” For that, we would have to wait until Keefe called Dwyer.

A few minutes later, when Keefe was again slow to object—this time to an insignificant but leading question—Tom McKenna popped up and said, “Objection.”

Skinner sternly sat him down. “Just one trial counsel, please.”

“I’m sorry,” said McKenna, sitting back in his chair.

“Decide who’s going to try the case,” Skinner snapped.

Keefe then made the objection and Skinner overruled it.

The old man’s last question was: “Prior to them getting out of the car, did you ever see badges on them?”

“No.”

“Thank you.”

Skinner said, “Cross-examination, Mr. Keefe?”

“Yes, Your Honor,” replied Keefe, slowly rising.

After O’Brian had given forty minutes of wholly credible testimony, Keefe squared off with our star witness. He began with questions about “the processes by which” O’Brian and Kobre “got to have permission to go in these [ACU] cars,” and proceeded to questions about “the nature of [O’Brian’s] handwriting . . . on the portion of [the reporter’s] notes that dealt with . . . waiting on Gurney Street,” and many more about overheard “radio communications.”

Having skipped over the shooting, Keefe thought he caught O’Brian in self-contradiction with his deposition when he said the Fabrique Nationale was found about an hour later.

“Now,” said Keefe, “did you attend a deposition in Mr. O’Donnell’s office on May 18, 1977?”

“Yes.”

“Was your testimony different at that time?”

“I pray Your Honor’s judgment,” said the old man softly.

He was objecting to only the most blatantly improper stuff, and this qualified. Keefe was supposed to show O’Brian his deposition before asking him if his previous testimony was different.

Skinner sustained the objection, but not wanting to stop Keefe on a technicality, he asked him, “Do you have anything you want to show him?” Keefe didn’t understand. So Skinner said, “That is not the right way to do it, counsel. Come on up here.”

In a bench conference, Skinner told Keefe how to impeach a witness with a deposition. The old man and Michael listened in unalarmed. Then Michael handed the judge O’Brian’s deposition. He read the relevant lines, shook his head, and said, “He said an hour. . . . There is nothing inconsistent with that.” Skinner told Keefe to go to something else.

Finally, Keefe approached the shooting. “After you started to move in on Smith Street, at some point you ducked down behind the seat?”

“That’s true.”

“Could you tell us what position you were in behind the seat and where you were?”

“I was on the left, on the left-hand side behind the driver. And when I ducked down, I was like, I was on my knees with my head down.”

Keefe slipped over to the defense table to confer with McKenna. Thirty seconds later, he looked up and said, “No further questions.”

Toward the end of the fifteen-minute recess that followed O’Brian’s testimony, Doctor Luongo arrived and we agreed to put him on next. I told the City Hospital witnesses, who had been waiting without complaint since yesterday afternoon, that we would call them right after the doctor.

The two waiting benches in the hall were filled now. Harry Byrne, Billy Dwyer, and Mark Molloy were on one; Adolph Grant, Elsie Pina, Donald Webster, and Henry Smith on the other. The Bowdens stayed in the courtroom during this and almost every other recess. Eddie and Denny came out and joined the police section. Eddie immediately lit a cigarette. He and Denny so enjoyed the chance to chat, joke, and smoke that, from then on, they would only intermittently leave their friends to subject themselves to the tensions of the courtroom.

On the way to the men’s room the old man asked, “Did you see Cohen’s face when O’Brian went through the ‘Fuck him’?”

“No,” said Michael. Almost everything happened behind Michael’s back. To his sides he could see the witness stand and the foreman. To see the rest of the jury or whichever lawyer was on his feet, he had to turn around—something he did only to get messages to the old man.

“You should’ve seen him,” I said. “Cohen’s definitely with us.”

“Too bad he’s not in the front row,” said Michael, unencouraged by the news that we had won the first alternate, who would have no say in the verdict.

David Cohen was the only juror we referred to by name because he was the one we talked about the most. He earned the distinction by being so expressive. When Walter Logue had to change his story, Cohen’s eyebrows jumped with surprise. When the old man was tying up John Tanous with the turret tape, Cohen, an engineer, smiled knowingly. He hung on every word of Kobre’s and O’Brian’s testimony, and when O’Brian calmly said, “Fuck him,” and, in imitation of Denny’s accompanying gesture, gripped both hands on an imaginary gun, Cohen, perhaps unconsciously, sighed, lowered his eyes, and shook his head.

Immediately after Doctor Luongo took the stand, Keefe, in a bench conference, objected to the anticipated introduction of the autopsy photographs. “Perhaps Your Honor would like to see them,” he said.

“Sure,” said Skinner.

Michael handed them to the judge, saying, “They show the entry wounds.”

The old man chipped in: “They were taken by the doctor.” Tom McKenna said, “The doctor can [simply] explain where [the bullets] entered.”

“I feel, Your Honor,” said Keefe, “the showing of the photographs would be prejudicial to my clients and it would be inflammatory and go to the emotional factor as opposed to—”

“Oh, heavens, no,” said Skinner. “It seems to me quite relevant where the wounds are. . . . These don’t strike me as being at all inflammatory. You just haven’t seen inflammatory pictures.”

“I suppose I haven’t,” Keefe replied.

Skinner told him about pictures he had once seen of “some woman worked over with an axe.” Prosecutors, he said, always “bring those pictures in.”

At lunch that day, the old man said, “You can never leave out pictures of the body in a murder trial. And even if the boys from City Hall still don’t know where they are, you can bet your life that the Honorable Walter Jay Skinner knows we’re really in a goddamn murder trial.”

And that night, Michael explained to Bill and me: “The standard routine with a medical examiner is to get his report into evidence and ask what the cause of death was. Most guys would’ve had Luongo on and off the stand in five minutes. You know, a little technical interlude. Nothing interesting about it. But what the old man did with him . . . that was . . . that was magic.”

What the old man did with Luongo—while Bill kept Eurina and Jamil occupied with coloring books out in the hall—was first to make his report plaintiffs’ exhibit number 14A, then to read selections of it to the jury, applying emphasis where he wanted it. Luongo sat with nothing to do as his report, the only heavily technical one in the case, got a caring and compelling reading in spite of itself.

The old man spoke slowly and softly, occasionally stressing a few words: “The body is that of a young black man.” Pause. “Who appears to be about twenty-five years of age, measuring sixty-four and five tenths inches in length and weighing an estimated one hundred and eighty pounds.” Pause. “The hair is black and kinky with an Afro-style hairdo.” Pause. “The only external evidence of recent injury consists of gunshot wounds.” Pause.

“There is a gunshot entrance wound in the left upper arm. This wound is oval in shape, measuring six tenths of an inch. [It] passes through the musculature of the left arm straight towards the left upper chest . . . with a perforating tract of destruction.” Pause. “The tract thence is into the wall of the esophagus where the bullet lies.” Pause.

“There is [a] gunshot wound in the left upper back.” Pause. “This entrance wound measures one inch by five-tenths of an inch. [It] passes through the skin and subcutaneous tissue [with] a perforating tract through the left scapular.” Pause. “The bullet lies lodged near the parietal pleura here at the end of the wound tract.” Pause.

“There is a gunshot entrance wound in the right posterior neck.” Pause. “This is nearly round, measuring four tenths of an inch in diameter. Exploration of this tract shows a destructive path through the subcutaneous tissues and muscles of the neck. The track ends just below the right jaw, the bullet lying here just beneath the skin without exit wound.”

Pat Bowden was as stoically expressionless as she always was during the trial.

The old man had Luongo leave the stand and join him in the middle ground between the counsel tables. Offering the doctor his pointer and himself as a model, he asked him to point out the locations of the wounds. Luongo put the pointer on the old man’s left biceps, then on the back of his neck at the hairline and on his back, while the old man fixed a mournful look on the jury.

He took the autopsy photographs from Michael and led Luongo to the jury rail. Holding the pictures for him, the old man had the doctor point out the bullet holes for one juror at a time. The foreman squinted and cringed. Cohen grimaced angrily.

The old man thought he was finished with Luongo, but Michael pushed him back out on the floor with a few more questions.

“Was James Bowden in any way in a bloated condition?”

“No, sir.”

“Are the lighting conditions at that part of the morgue where people make [identifications] adequate for a person to make an identification?”

“I think so.”

“Have you seen people identify bodies there?”

“Oh, yes, many times.”

“Thank you,” said the old man, as he sat down.

Working without notes has its price. The old man had forgotten to ask the two standard questions always put to medical examiners: “Did you form an opinion as to the cause of death?” and “What is that opinion?” With the old man in his seat, Skinner asked those two questions, and Luongo said, “The deceased came to his death as a result of gunshot wounds” and consequent “massive internal hemorrhage.”

“Cross-examination?” asked Skinner.

“I have no questions,” said Keefe.

Henry Smith, the head of City Hospital’s Housekeeping Department, was our next witness. Through him, the old man showed that Bowden had been working at the hospital since 1968.

Consulting his file, Smith testified that Bowden’s income rose from $4,352 in 1968 to $6,927 in 1974, his last full year on the job. He said that Bowden’s “work performance” was “satisfactory” and he never had to “penalize him or suspend him or anything.”

“Do you have a time card for Mr. Bowden regarding January 29, 1975?” asked the old man.

“Yes,” said Smith, handing it over.

The old man offered it as an exhibit, and Keefe objected. Skinner called a bench conference to find out what Keefe’s objection was. At the side bar, the old man gave Skinner the time card and Keefe said, “Some other person besides Mr. Bowden [could] have punched the card out.”

“You can get into that on cross-examination,” said Skinner. He handed the card to the clerk and said, “That is admitted.”

Keefe soon made his point in a succinct cross-examination:

“What time was the end of the shift for the housekeepers?”

“Three-thirty. Normally, they have to punch out at three-twenty, around that time.”

“How many people are usually punching out at that time?”

“Roughly about a hundred and twenty-five.”

“As the people are punching out, is it possible for a person to punch out the wrong card?”

“It’s possible.”

Keefe resumed his place at the defense table without, I think, noticing that his clients had missed his first moment of triumph. They hadn’t yet returned from recess.

The old man bobbed up for two more questions:

“Do you make any provisions to guard against a person punching out someone else’s card?”

“Yes . . . several supervisors, as a rule, are in the same room, plus the office clerks, and they would know if an individual makes a mistake [and would] so note it.”

“And was anything called to your attention about Bowden’s check-out time on January 29, 1975, by any of these supervisors?”

“No.”

“Thank you,” said the old man. “That’s all.”

That made for a neat transition to Donald Webster, who passed Henry Smith in the doorway. Webster testified that he was one of the supervisors at the time clock that day and that he saw Bowden punch in “at seven o’clock in the morning” and punch out “at twenty minutes past three.”

“That’s all,” said the old man.

Skinner invited cross-examination with a simple “Mr. Keefe?”

Keefe listened to a minute or two of agitated whispering from Tom McKenna before going to the lectern. Once there, he asked, “Mr. Webster, did you assign Mr. Bowden somewhere that morning?”

“Yes.”

“Where did you assign him?”

“Children’s Building,” replied Webster.

“I see,” said Keefe. “No further questions.”

So much for the someone-else-punched-out-for-him theory.

The old man tried one more question. It was an objectionably leading one which reminded Webster that he clearly remembered Bowden punching out because there was some jostling in the line near him. Keefe was slow to object, and Tom McKenna jumped up in his place. McKenna caught himself before objecting, though, and sank back in his chair, saying, “I’m sorry, Your Honor. I apologize.”

Keefe finally said, “Objection.”

“Sustained,” said Skinner. To McKenna, he added, “If Mr. Keefe is going to try the case, he is going to try the case, and you stay out of it.”

The old man turned to me and rolled his eyes in ecstasy.

Enter Elsie Pina. The old man was ready for trouble. If she tried to move the last time she saw Bowden back to two o’clock, he was going to hit her with her report saying it was two-fifteen. The old man, report in hand, got to the point of confrontation in less than two minutes.

“Will you kindly state your name?”

“Elsie Pina.”

“And where do you work, Miss Pina?”

“At the Boston City Hospital.”

“What are your duties at the Boston City Hospital?”

“I’m a supervisor in the Housekeeping Department. . . . I’m in charge of the Children’s Building.”

“And were you working there on Wednesday, January 29, 1975?”

“Yes, I was.”

“Did you know one James Bowden?”

“Yes, he worked with me that day.”

“And do you recall what assignment you gave him?”

“Oh, yes. He was in charge of the clinics, to take care of the clinics.”

“What time did you first talk to him?”

“I talked to him in the morning, and then after coffee break because he didn’t do such a good job. And then I saw him in the afternoon.”

The old man had been leaning against the jury rail. Now he moved slowly toward Pina, and looking at what she could tell was her report, he asked: “And what time was it in the afternoon that you saw him?”

“Well . . .” Pause. “I would say about two-thirty.”

The old man spun on his heel. “That’s all, Miss Pina.”

My mind was so set on getting her to say two-fifteen that I didn’t, for a minute, realize that two-thirty was better. I wondered why the old man wasn’t up there stuffing two-fifteen down her throat and putting her report in evidence. By the time the shock passed and I caught on, Keefe was at the lectern.

Keefe could have introduced Pina’s report and tried to push her back to two-fifteen. But for what? That would be as good an alibi as two-thirty. Keefe ignored the two-thirty and asked how often Bowden worked for her.

“He only worked for me about three times,” said Pina. “It just so happened that the steady man I had called in sick.”

“Who was that?”

“Donald Shaw.”

“So the day Mr. Bowden worked for you, that was the day Mr. Shaw called in sick?”

“That’s right.”

“No further questions, Your Honor.”

The Donald Shaw stuff sounded like more Keefe-elicited trivia. It would turn out, however, to be a seed Keefe planted for the defense case.

It was twelve-fifty-five when Pina left the stand, and Skinner said it was time for lunch.

As soon as judge and jury left the room, the old man came over to me and said, “Think we should use Adolph Grant?”

“Why not?”

“Well, Elsie already put our guy in the hospital at two-thirty.”

“Yeah. And Adolph Grant can corroborate.”

“But she was solid. And he’s just gonna add that our guy was duckin’ work with him.”

“So what? Everybody’ll believe him. He’s good.”

“So, I don’t want the jury thinking James Bowden wasn’t exactly the hardest worker in the joint. And I really don’t want them to know he could sneak out of sight like that.”

“Hiding in the basement isn’t the same as driving to Cambridge.”

“Yeah, but what good does it do us now that we already have our guy in the hospital at two-thirty?”

I told Adolph Grant he wouldn’t have to testify. “We’ve already proved James was at work,” I said. I thanked him for his patience and released him from our subpoena.

I then raced out to collect our lead-off witnesses of the afternoon: Jessina Stokes and Carla Davis. Jessina had moved from Mission Hill to another project, and Carla had moved to a two-family house on a tree-lined street in a black section of Dorchester. They were still best friends. I picked up Jessina first. She directed me to Carla’s house. As the three of us rolled past Dorchester Avenue’s unair-conditioned movie theater, its pizza places, liquor stores, gas stations, and its from-here-to-the-horizon array of bars, the girls exchanged favorable judgments of each other’s clothes. They were in tasteful pantsuits—just what we, if consulted, would have suggested. Both of these thirteen-year-olds were, to say the least, nervous. They were on their way to speak, for the first time in their lives, under oath, through a microphone, to a roomful of adults—white adults—two of whom they had seen kill someone.

They were worried about what the police would try to do to them in the courthouse. I told a double lie: The cops were afraid of us O’Donnells and the FBI would be there to protect them. They seemed to go for the FBI part, but they still didn’t like the idea of having to give their new addresses in court. The cops would know where to find them. I told them that we’d always protect them. They weren’t impressed.

Toward the end of Dorchester Avenue, Carla whispered to Jessina, “Are we in Southie?”

I lied again: “No, this is the South End.”

We would have cleared this corner of Southie in a minute with the girls none the wiser were it not for the unofficial welcome-to-Southie sign coming up. Carla saw it first. It was spray-painted by a shaky hand on the lower right corner of a billboard advertising cigarettes. Big black letters. Two words: KILL NIGGERS.

This is not uncommon Boston graffiti. In Southie it’s about as common as the street signs. In the six months that I once spent as a substitute teacher, I saw it inside many Boston public schools. The white janitors in the school system are reasonably quick to remove anti-white graffiti but seem to have trouble finding the time to get rid of the anti-black messages. For over four months in 1980, a toilet stall in Boston Latin Academy, the city’s second-best public high school, carried these gems, all written by the same excited hand:

WHITE PEOPLE (A) ARE SMART (B) ARE RICH (C) ARE PRETTY (D) ARE NOT BLACK (E) EAT GOOD FOOD (F) DON’T HAVE DISEASES (G) DON’T THROW SPEARS (H) DON’T LIVE IN ROXBURY (I) LIVE IN SOUTHIE (J) KILL NIGGERS

REMEMBER, NIGGERS, THE KKK IS AND ALWAYS WILL BE HERE TO STAY!

IRISH POWER

Plaintiff’s exhibit 16: Identification card of James Bowden, Jr.

Plaintiff’s exhibit 135: Patrolman Billy Dwyer, moments after the shooting of James Bowden, Jr., asking reporter Dave O’Brian: “How’s this for action? Did we put on a good show for you?” (PHOTO © KEN KOBRE)

Report by Patrolman Dennis McKenna

Patrolman Dennis McKenna walks around the left front of James Bowden’s crashed Buick. The smears on McKenna’s right hand are Bowden’s blood. (PHOTO © KEN KOBRE)

Plaintiff’s exhibit 7B: Report by Patrolman Edward Holland

Patrolman Edward Holland shakes a cigarette out of a pack after the shooting. Bystander with back to camera in foreground is unidentified. (PHOTO © KEN KOBRE)

Upper left, Dennis McKenna. Center, Edward Holland. Right, Mark Molloy. Note license plate number on Bowden’s car. (PHOTO © KEN KOBRE)

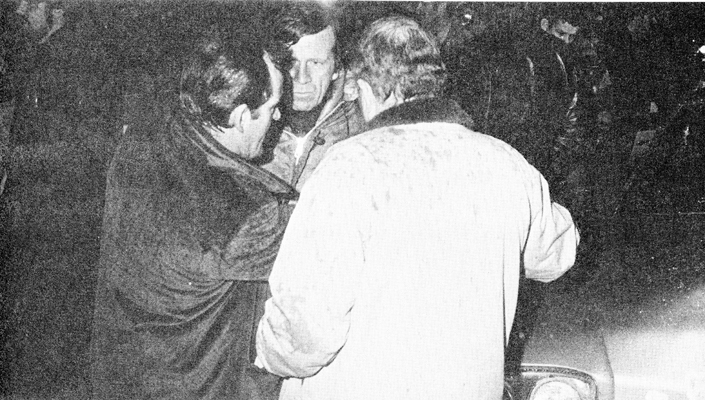

Edward Holland, Billy Dwyer (center), and unidentified officer confer after the shooting. (PHOTO © KEN KOBRE)

Ballistician Walter Logue unloads the pistol found by Patrolman Joe Fagone. (PHOTO © KEN KOBRE)

Patrolman Joe Fagone discovers the pistol under a parked Chevrolet. (PHOTO © KEN KOBRE)

Jessina and Carla, both ninth-graders then, must have seen such stuff before. Nevertheless, they spent the next five minutes on the floor of the car in O’Brian-Kobre style and wouldn’t get up until we were downtown. I don’t recall being much concerned about how an experience like that would affect these girls’ lives; I just remember worrying that it might affect their performance on the stand.

We put Jessina on first. Bill and Mary stayed with Carla out in the hall. Eddie and Denny were in their front-row seats.

The old man began by having Jessina point to her window on the model. Then, over Keefe’s objection, he introduced a photograph of her building taken from the shooting spot and had her identify her bedroom window in the picture. He handed it to the foreman and got to the point:

“On Wednesday, January 29, 1975, were you in your home in the early evening?”

“Yes.”

“And where were you?”

“I was looking out my bedroom window.”

Jessina blushed at the sound of her amplified voice.

“Were you talking to anyone?”

“Yes.”

“With whom?”

“To my friend Carla Davis.”

“And where was Carla Davis?”

“She was at her home looking out the window.”

“Did you observe something?”

“Yes.”

“Tell the court and jury what you observed.”

“I observed two men jumping out of a car. And they was running toward another car. And one was holding on to the handle of the car. And they started firing at the person in the car. And I saw the flames of the bullets.”

“And did you hear any voices from the two men that were firing at the car?”

“No.”

Thus, the ball rocketed into the defense’s court, where Keefe had to return it with the utmost delicacy. He couldn’t aggressively cross-examine a little girl without looking like an awful bully. He had to be friendly and gentle, and he had to attack her story. And since she hadn’t been deposed, he had to ask questions whose answers he didn’t already know. Considering the circumstances, he did a fine job.

His opening was predictable: “Are you related to the Bowden family?”

“Yes . . . James Bowden was my mother’s brother.”

Then he picked at details: “What was the temperature outside?”

“It was like a spring night.”

“Was the sun out? Was the sun down?”

“It was dark.”

“What were you talking to your friend about?”

“I don’t remember.”

“Did you do this often?”

“Yes.”

“What were you wearing?”

“A pair of pants and a shirt.”

“What kind of shirt?”

“I don’t remember exactly what kind of shirt I was wearing.”

Keefe was smiling and calling Jessina by her first name, but she knew she was being tested. Her voice became softer.

Skinner told her, “The jurors can’t hear you very well. . . . I tell you what: You talk to them just as loudly as you would talk to Carla. Pretend you’re leaning out the window and shouting to these people, okay?”

“Okay.” Jessina smiled.

Keefe asked Jessina to point to the spot on the model where the shooting occurred. The old man handed his pointer to Keefe, who passed it along to Jessina. She pointed to the right place. With Jessina still standing uncomfortably at the model, Keefe asked for more details and stumbled into something very helpful.

“Could you tell us what the men were wearing?”

“No.”

“Did you see the color of their car?”

“No.”

“Did you see them get out of the car?”

“Yes . . . I just saw like—I looked at the car while I was talking, and then I turned back and started talking. I didn’t pay no mind. But I did see them jump out, and then I saw them run up to this car.”

“How long did you talk to Carla Davis after you first saw the men on the street?”

“A minute. I don’t know.”

“Then, you turned back to the street, and you saw the bullets?”

“Yes.”

Skinner intervened to tell Jessina she could go back to the witness chair.

Keefe huddled with Tom McKenna, then sat down. They glowed with delight.

Eddie and Denny smiled.

Had we based our case mainly on Jessina’s testimony, we would have been in trouble.

Since Jessina had not told us that she took her eyes off the action at any point, the old man thought she was confused and tried to get her straightened out with a simple question: “What did you observe the men do?”

“Run up to this car,” she said, “and start firing bullets.”

“Did your eyes stay right on them while they were doing that?”

“Yes.”

“And you had something to say to Carla?”

“Objection, Your Honor,” said Keefe.

It was a leading question, but the tradition and the federal rules allow you to lead “the child witness.” Skinner said, “Overruled,” and asked the question himself.

“I asked her did she see the bullets,” said Jessina, “and she said yes.”

“What do you mean by seeing bullets?” Skinner asked.

“I saw a blue flash.”

“Did you hear the sound of a gun?” he continued as the old man sat down.

“Yes.”

“How many bangs did you hear?”

“About six, seven, something like that.”

“Recross, Mr. Keefe?”

Keefe conferred with Tom McKenna for a minute before getting up again.

“Jessina, when you first saw the men,” he began, “you saw them get out of their car.”

“Yes.”

“And they were in the street about a minute.”

“I don’t know,” said Jessina. “All I know is I saw them get out of this car and start running towards this other car.”

And so it was left.

Carla Davis, whom we called just to confirm that Jessina was at her window, had an easier time on the stand. After a minute of preliminaries, the old man asked, “While you were talking to Jessina, did something happen on Smith Street?”

“Yes.”

“What happened?”

“Well, one car, you know, came zooming down Smith Street and was going kind of fast, you know. We weren’t paying no attention to it. Another car came, and it stopped and a bullet fired, and Jessina saw it and she asked me if I saw it, and I said no. And she told me to look over there and I saw another shot and I got out of the window. We were both scared and got out of the window.”

“That’s all,” said the old man.

“Mr. Keefe?”

“One moment, Your Honor,” said Keefe. Tom McKenna was whispering something to him.

Keefe tried a couple of detail questions. Carla did not remember what the temperature was or what she and Jessina were talking about. Then he asked only one question about the action: “You heard Jessina say she saw a bullet?”

“She didn’t say she saw a bullet,” replied Carla. “She said, ‘Look.’ And I looked at her, and we both saw another bullet. She saw one and she told me to look at it.”

The old man thought that that clarified the girls’ testimony.

Our next witness was a man who, when asked about his occupation, said: “I’m the Assistant Deputy Commissioner of Fiscal Service for the Department of Health and Hospitals of the City of Boston.” Through him we introduced some City Hospital payroll records which Henry Smith had not been able to provide. They included the kind of fine points of Bowden’s income history that Jack Marshall, our actuary, was going to mention in his testimony.

After a five-minute recess, the old man called the last witness of the day: Patricia Bowden. Our shy, private plaintiff was, she told me, “terrified” by the thought of testifying, though she had known for months that it would come to this.

“I don’t want to talk about James,” she told the old man during the recess. “I still can’t do it without crying.”

His response was false: “We’re just going to introduce exhibits, and I’m going to ask you a few things about the kids. You know, we’ll show that they’re plaintiffs, too, and they’ve got a claim here.”

We had three things to cover with Pat. First, that the Bowden license plate was 4F•6838 and that the front plate had been stolen two days before the shooting. Second, that the Bowden family was a legal entity with the right to sue on James’s behalf. Third, that Patricia, Eurina, and Jamil had lost not only James Bowden’s financial support but also the intangibles that the wrongful death statute allows compensation for: his “services, protection, care, assistance, society, companionship, comfort, guidance, counsel and advice.”

Wrongful death plaintiffs always cry—sometimes spontaneously and sometimes on the advice of counsel—when testifying about the intangibles. A nice, dignified cry, nothing hysterical that would interrupt her testimony, just an occasional stream of tears—that’s what we were hoping for.

Exhibit introduction went smoothly. Keefe made no objection.

“I show you that piece of paper and ask you to examine it.”

“This is our marriage license.”

It was admitted into evidence, as were James’s, Patricia’s, Eurina’s, and Jamil’s birth certificates, and James’s death certificate. Then came the Buick’s certificate of registration, the permit James obtained on January 28, 1975, allowing him to drive with one license plate, and finally the replacement plate the Registry sent two months later.

After the exhibits were in, virtually all of the old man’s questions were leading, but Keefe wisely did not object. The moment belonged to Patricia Bowden, and Keefe knew that no one would welcome his interference.

“Now, it’s so, isn’t it, that you are the unmarried widow of James H. Bowden, Jr.?”

“Yes.”

“During the five years of your marriage, did Mr. Bowden support you?”

“Yes.”

“Did he work continuously at Boston City Hospital?”

“Yes.”

“Did he have a criminal record?”

“No.”

“Did you live together during that period as husband and wife?”

“Yes.”

“And you both had, as a result of your union, these two children?”

“Yes.”

“And during that period of time, did he give you any help with your daughter, Eurina?”

“Oh, yes.”

“What did he do that you can tell the court and jury about regarding your daughter?”

“Well . . .” Pause. “He used to take us to movies and to the circus and different things.” Pause. “He was a good father.”

“Did he give her guidance and care?”

“Yes.”

“What time would he generally get home from work?”

“About four o’clock.”

“Would Eurina be home from school then?”

“Yes.”

“And what, if anything, would your husband do with his daughter at that time?”

“Well. He would play with her. Talk to her. They would sometimes watch cartoons for a little while.”

“Your husband had relatives living on Smith Street in Roxbury?”

“Yes.”

“Did he have a custom regarding visiting there?”

“Yes. Mostly everyday he would go over after supper.”

“Because who was living there then?”

“His mother.”

“And when your son was born, what, if anything, in care and help and society did your husband do regarding your son?”

The old man was standing behind Michael now with a hand on the back of his chair.

“Well,” said Pat, “he helped me a lot with him.”

The old man looked at the floor and took a deep breath. Pat’s composure was flawless, but he was on the edge. He kept his back to the jury.

“On Wednesday, January 29, 1975, did he come home after work?”

“Yes, he did.”

“Was Eurina there?”

“Yes, she was.”

“And did any conversation go on between your husband, James, and Eurina?”

“Well. James wanted to take her—you know—she wanted to go over to Ma’s. That’s what I call my mother-in-law. But I was getting ready to bathe the baby, and she wanted to help. So I told her she didn’t have to go; she could stay with me.”

The old man nodded and, still looking at the floor, asked, “At some time in the evening, did you go to the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital?”

“Yes. I did.”

“Did you receive some information there?”

“Yes. I did. I went into the hospital. I was directed to the emergency ward. And I saw my husband.” Pause. “He had just passed away.”

Long silence.

“Now . . . with James Bowden, you offered one another love and affection?”

“Yes.”

The old man looked at Pat as he sat down. “And did that continue up until the time he was killed?”

“Yes.”

From his chair, with eyes closed, in a weak voice the old man asked, “Does it continue to this day?”

“I still love him,” Pat whispered.

Into the stillness, Keefe mumbled, “No questions, Your Honor.”

Skinner said quietly, “Thank you, Mrs. Bowden.”

Pat left the stand without having shed a tear.

A few minutes later, she was able to recall very little of her testimony.