From midnight until 4:25am, when the police were officially called, the traffic in and out of Marilyn’s Brentwood home was compared to that of Grand Central Station. Many concerned men and women who passed through the murder house that night later denied they were even there.

Much was riding on a hastily written scenario by Arthur Jacobs, with the goading of 20th Century Fox. He was put in charge of rearranging and re-choreographing the scene, an old Hollywood trick that dated back to the 1930s and the mysterious death of Paul Bern, Jean Harlow’s ill-fated husband.

There was almost no talk of a gangland execution or of its ringleader, Sam Giancana. The Kennedy brothers were the first and almost only consideration. After all, the fate of a political dynasty was at stake. The future political map of America, and by extension the Free World, could be whirling around the dead body of this blonde love goddess, who at that moment in Hollywood was its most celebrated actress.

There were two major objectives, and Jacobs had to achieve both of them—namely, to establish that Marilyn’s death was a suicide, and second, to destroy evidence of any possible romantic link between her and the Kennedy brothers, Bobby and Jack. Teddy was such a minor player in the drama that almost no one seemed aware that he, too, knew Marilyn and had visited her for private encounters at Brentwood.

If Marilyn’s death were ruled a suicide, there would be no investigation. But if the police defined it as murder, then an investigation would be launched that might lead anywhere, even to the White House.

Before the police were alerted, the household had to be made camera ready, just like a movie script.

More arrivals at the house were on the way, but it is believed that, in addition to Marilyn’s dead body, she had any number of guests at around midnight: Peter Lawford, Pat Newcomb (although she denied it), Eunice Murray and her son-in-law Norman Jeffries, and Dr. Ralph Greenson, who had been joined by Marilyn’s doctor, Hyman Engelberg.

Lawford set about removing “the paper trail,” as he called it, which linked Marilyn to the Kennedy brothers. From her filing cabinet, Lawford was said to have filled three cardboard boxes with her personal papers and other documents. Normally, it would have been locked, but someone had broken in only two weeks before and robbed many of her documents. The lock had never been repaired, although she meant to call a locksmith.

Lawford’s greatest discovery, or so it was alleged, was her red diary, which he confiscated and removed from the filing cabinet. Eunice Murray had seen Marilyn writing in it Friday. Marilyn had given Eunice the diary to put back in the filing cabinet, from which it was later stolen.

Reportedly, all of these documents, including the diary, would, within a few days, be carefully shipped to the Department of Justice marked “for the eyes only” of the Attorney General.

Jacobs wanted Marilyn’s body moved from the guest cottage into her bedroom. Eunice was ordered to wash the soiled sheets that were left behind, and to make up the bed again as if it had not been used that night.

Jacobs, the consummate press agent, reportedly said, “Fox will generate lots of money on Marilyn’s pictures for years to come. We can’t have our love goddess discovered in a pile of shit. How in the fuck would that look?”

With the cooperation of Marilyn’s psychiatrist (Greenson) and medical doctor (Engelberg), a fictional plot had to be quickly and carefully devised as to how her body had actually been discovered.

Jacobs had spent most of his life reading scripts. For casual reading and relaxation, he preferred murder mysteries. Frantically, he set about creating his own movie-inspired plot.

Like a good film, the story of Marilyn’s suicide would have a beginning, a middle section, and a dramatic conclusion. The press agent decided that the plot needed to begin at the Santa Monica mansion of Patricia and Peter Lawford. Although still intoxicated, Lawford would have to be rehearsed in a credible scenario of events.

In his subsequent investigation of Marilyn’s death, Robert Slatzer tried to answer why Jacobs was on the scene managing and spinning the story. Slatzer later claimed that Jacobs was there to rearrange Marilyn’s death in such a way that the studio could collect a three-million dollar life insurance policy it held on its star.

After Marilyn’s death, Fox was most gracious to Jacobs. He not only sold his agency for a huge amount of money, but became a producer at Fox. His first assignment was to direct What a Way to Go, a picture that had originally been developed specifically for Marilyn. He followed that with his mega-bucks release of The Planet of the Apes, with all the spin-offs it spawned.

It would have been logical for Jacobs to summon his “Marilyn Monroe expert,” Pat Newcomb, to the scene that night. But as pointed out, she denied ever being there. Yet, after Jacobs died, his widow, Natalie, said, “If you really want to know what happened that night, ask Pat Newcomb. She knows the whole story.”

The evidence is overwhelming. All of the key witnesses at the scene of the crime told stories about their involvement that were substantially untrue—and, in most cases, a blatant lie.

As the years went by, key witnesses, perhaps forgetting what they had originally said, changed their testimony. In some cases, as these witnesses neared their own deaths, they admitted some of their previous testimony had been untrue, as in the case of Eunice Murray.

The biggest lie that some of the people who were in the house that night told was, “I wasn’t even there. The first time I heard the news was over the radio when I woke up that Sunday morning.”

***

Peter Lawford’s account of what happened on the night Marilyn was murdered depended on what year it was and who he was talking to. He invented various dialogues that were probably never spoken, especially the remark about her telling him to “say goodbye to the President.” In some of his other versions, it was, “Say goodbye to Jack.”

It appears that he did make a call to Marilyn at around seven that evening, as reported in Part Five of this book. She was coherent, based on statements made by friends who called her that night.

Lawford later claimed that Marilyn called him and allegedly told him, “I can’t take it anymore. It would be better off if I killed myself.”

He claimed that she’d said that at the time, but that he did not take the threat seriously, as she’d made so many suicide attempts in her past. At first, he reported that he responded, “For God’s sake, Marilyn, don’t leave any suicide notes behind.

”Later, he must have realized how heartless that sounded, so he greatly altered his version of what was said between them.

At his home after 8pm on Saturday, Lawford told one of his dinner guests, George (“Bullets”) Durgom, that he was worried about Marilyn, as he had tried to reach her several times on the phone, asserting that her line was busy. When he called the operator, she reported to him, or so he said, that her phone was off the hook. He had the number of her second phone line, but there was no mention of his attempt to dial that back-up number.

Then from the context of the party at his house, Lawford opted to phone his agent, Milton Ebbins. Lawford had, prior to his call to Ebbins, spoken to someone else on the phone, a person rumored to have been Bobby Kennedy, although that was never proven.

Lawford reported to Ebbins that “Marilyn’s voice was barely audible, and she seemed distressed, disoriented, her speech slurred.” He seemed to over-state the situation. Had Lawford been instructed to begin inserting the suspicion that Marilyn had been contemplating suicide that night?

Even though he was hosting a Chinese take-out dinner within his home that night, Lawford asked Ebbins advice about whether he should excuse himself and drive over to Marilyn’s home.

“You can’t be caught there if there’s trouble,” Ebbins told him. “Hell, you’re the brother-in-law of the President of the United States. Let me get in touch with Greenson or her lawyer.”

Ebbins was unable to reach Greenson by phone, but he did get to speak to Mickey Rudin, Marilyn’s lawyer. Ebbins telephoned Rudin at around 8:15pm, getting his answering service. Asserting that it was an emergency, the answering service eventually located Rudin at a cocktail party at the home of Mildred Allenberg, the widow of the late agent from William Morris, Burt Allenberg, who had represented Frank Sinatra.

Alerted to Lawford’s concern, and as a means of handling the matter, Rudin placed a call to Marilyn’s home. Her second line wasn’t busy, and Eunice picked up the phone. She was getting ready to go out to dinner with her son-in-law. Rudin told her about Lawford’s concern and asked Eunice to go to Marilyn’s bedroom and check on her.

Rudin claimed that he waited four minutes for Eunice to come back onto the telephone line. Then Eunice told him, “She’s fine.”

Rudin later claimed that he suspected that she never bothered to look, or else that she knew what was really going on in the house that night and didn’t want him to know. Rudin then claimed that he called Lawford back, telling him, “Mrs. Murray said that Marilyn is just fine.”

With Lawford at his party in Santa Monica that Saturday night were Joe and Dolores Naar, who lived only four doors from Marilyn.

“It was a fun evening,” Dolores later recalled. “Peter got quite drunk. He gave no indication during dinner that anything was wrong. But he was called away at one point. When he came back, he explained that a phone call he’d received was from Marilyn, ‘who is very tired and can’t come over.’”

At that time, the Naars were about to leave. It is believed that the anonymous caller who had previously spoken to Lawford was not Marilyn at all, but someone else, warning him about something.

The Naars left Lawford’s party in Santa Monica and were home after around 10pm. Dolores Naar later asserted, “As Joe was getting undressed, he got this urgent call from Peter. Joe said he sounded like he was in a panic. Peter asked Joe if he’d go down and knock on Marilyn’s door and see if she were all right. Peter told him he was afraid that she might have taken too many pills.”

“I put on my clothes again and was rushing out the door when another call from Peter came in,” Joe said. “Strangely, he told me not to go to Marilyn’s. ‘Everything’s okay,’ he said. ‘I’m just an alarmist. You know me, the old worry wart.’”

Lawford obviously didn’t want Naar to go to Marilyn’s, afraid by now for what his friend would discover. If he’d gone, Joe might even find Lawford arriving there himself.

Some time after 10pm, Lawford was spotted leaving his Santa Monica home, in his Mercedes, by a neighbor, Billy Ward. Peter, according to the neighbor, was staggering toward his car when the unidentified woman who was with him opted to get behind the wheel to actually drive the car. Later, it was believed that the woman was none other than Pat Newcomb, who was reported to have been a guest at Lawford’s party that night, even though she’d originally begged off from attending, complaining of a sinus infection.

It was only an eight- to ten-minute drive from Santa Monica to Marilyn’s residence in Brentwood. Lawford and Newcomb were believed to have arrived in Brentwood at 10:35pm, three minutes before the ambulance.

Lawford’s maid, Erma Lee Riley, later claimed that her boss never left his house and that he was there all night. Had she gone to bed early? Or was she trying to protect her job? Many other witnesses placed Lawford at Marilyn’s home well before midnight.

When Dolores Naar heard of Marilyn’s death, she said, “No wonder Peter didn’t want Joe to go over there that night. Peter heard from Jack or Bobby—probably Bobby—who told him to get over there and clean up the mess himself before the police and press arrived.

”Lawford would later claim that he did not learn of Marilyn death until 1:30am, although he refused to name who’d told him. This was obviously a lie, as he was deeply involved in the cover-up before midnight.

Deborah Gould, Lawford’s third wife, said, “He told me he went over there and tried to tidy up the place and remove anything linking Marilyn to the Kennedys before the police arrived.” Gould also claimed that Lawford told her, years after the event, “Marilyn took her last enema,” indicating that he knew the method of her death.

Jeanne Carmen later recalled that Marilyn was no stranger to enemas. “I saw her take a few myself. She was always complaining of chronic constipation.

”Fred Otash, the master detective and “bugger,” later claimed he received an urgent call from Lawford, who phoned from Marilyn’s house after she died. “It was at around midnight. I already knew, of course, that Marilyn was dead. I had my means of knowing that.”

“Peter wanted me to go over and remove any bugging equipment from the house, because he didn’t know how to do anything that elaborate,” Otash claimed. “I refused to go over there. I didn’t want to get messed up in that shit, which might lead to a murder trial.

”Otash said he advised Lawford how to get rid of some of the evidence. “Peter sounded like a fucking mess. It was like I was talking to a junkie going cold turkey.”

“Do what you have to do,” Otash told Lawford. “But get the shit out of there before someone else calls the police. I hope your buddy, Bobby, has gotten his skinny ass back into a San Francisco hotel by now.”

“He’s safe,” Lawford assured him. “But I don’t know what that fucking bitch might have written. She was always taking notes about things she shouldn’t have learned about in the first place.

”Otash claimed that he then asked Lawford the all-important question, “Did Bobby have anything to do with Marilyn’s murder?”

“Hell, no! He’s too smart for that.”

Of course, Otash, from listening to the tapes, already knew that Sam Giancana was behind Marilyn’s murder. But he voiced one question which was never answered. “Who was behind Giancana giving the orders that were passed on to Johnny Roselli? There was big money involved here, but I sure didn’t get my hands on any of it.”

When Lawford returned to his Santa Monica home, which was also bugged, it was around three o’clock in the morning, perhaps later. On his tapped phone, he received a mysterious call coming in from San Francisco. At the time, or so it is believed, Lawford had Marilyn’s private papers with him, including her red diary.

A secret recording picked up the sound of a man’s voice. “Is she dead yet?” he asked.

“Yes,” was all that Lawford said in response before the caller hung up.

According to Otash, “It did not sound like Bobby Kennedy’s voice, [but] a man’s voice much deeper.”

On the day of Marilyn’s funeral, Lawford was flying to Hyannis Port, where he would remain incommunicado. Before he left L.A., he told a reporter for The Los Angeles Herald-Tribune that he had spoken to Marilyn at around 7pm on the Saturday of her death. “She said she was feeling sleepy and was going to bed. She did sound sleepy, but I’ve talked to her a hundred times before and she sounded no different.”

All that seemed innocent enough, but by the time he reached the Kennedy compound in Hyannis Port, he told the clan, “I fear the shit’s about to hit the fan.”

[In 1992, thirty years after Marilyn’s death, it was revealed that Lawford had placed a call at 6:05am to the White House, where the time was 9:05am on Sunday morning, August 5, 1962. President Kennedy had returned to Washington from his time “at home” in Hyannis Port. The very first entry into the presidential phone log listed Lawford as the person who placed a call from a “Pacific Coast Highway” address in Santa Monica., where his private number was recorded as GL1-1800.

He and the President, according to the log, talked for twenty minutes.

To many reporters, this early morning call was viewed as the smoking gun that linked the President to Marilyn’s death. The call may have been no more sinister than Lawford giving JFK the inside scoop on what was about to explode into a nationwide media frenzy.]

***

At the murder house in Brentwood, Arthur Jacobs, ace publicist, continued his rearrangements of the scene before calling the police. He found the doctors, Greenson and Engelberg, cooperative, but when he encountered Eunice Murray, he defined her as “a difficult bitch to deal with.”

Mickey Rudin, the lawyer, also arrived at the Brentwood house that night, although he would deny it for years. In 1992, he finally admitted that he had, indeed, been there. “I got a call from Romi to come over,” he said, using his nickname for Dr. Greenson. “I was told that Marilyn was dead. I drove over right away. Newcomb was there. She was hysterical.”

His statement seemed to confirm the emotional state of the woman who James Hall, the ambulance driver, had encountered.

The spin about how Marilyn’s body was discovered remained a major concern. A scenario had to be worked out. Jacobs wanted Eunice to have come upon the body in Marilyn’s bedroom, and not within the cramped guest cottage.

Greenson and Engelbert had delicately moved the body into her main bedroom, and Jacobs had artfully arranged it. Marilyn remained nude, but a sheet was placed over her body.

Eunice was configured as the star witness. With help from the professionals on the scene, she began to spin a tale of discovery that would later prove to be moth-eaten.

At first, she said that she woke up after midnight to use the bathroom. On the way there, she noticed a light in Marilyn’s bedroom and her phone cord extending out from under the door.

A white carpet with thick, plush piling had recently been installed. With the understanding that the pile would eventually be crushed down through the course of daily use, the piling, shortly after the carpet’s installation, was so high that no light would have been seen beneath the door, and it’s highly unlikely that a phone cord could have been slipped under it. In addition, Eunice had the use of her own bathroom, and would not have passed by Marilyn’s bedroom as a means of reaching her own toilet.

Eunice would later claim that she attempted to enter through Marilyn’s door, but found it locked. There was one major problem with that assertion: There was no lock on Marilyn’s door. The housekeeper also said as a means of checking whether Marilyn was all right, she exited from the house, went into the garden, reached through the open window of Marilyn’s bedroom and, from the outside, “parted the curtains.” Eunice claimed that the lights were still on in Marilyn’s room and that she was lying on the bed with the phone trapped under her stomach.

Eunice said that she then went back into the house and telephoned Dr. Greenson on the building’s second phone line. He had just returned from dinner with his wife. Since he lived nearby, he said that he’d drive right over.

At the scene of the crime: Mickey Rudin

Eunice’s timing certainly appears to be off, because James Hall encountered Greenson in the hallway at the time of Marilyn’s death. To confound matters even more, Eunice would later tell the police that she didn’t find Marilyn dead until 3:45am, when rigor mortis had already set in.

There were other discrepancies: Marilyn’s bedroom windows had been bolted. There was no opening for Eunice to reach through as a means of parting those draperies. Although Marilyn had plans for the eventual fabrication of “black-out” draperies, they were not yet in place by the time of her death. Instead, Norman Jeffries had simply stapled a length of fabric over the windows as a temporary solution. The curtains could not have been parted from anyone standing in the garden, both because of the windows having been bolted shut and because of the way the bolt of fabric had been stapled into place.

A few weeks prior to her death, five high school boys, hearing that she had moved into the neighborhood, were caught as Peeping Toms trying to peer into her bedroom. Marilyn had always been sensitive about her privacy, and because of the fact that she liked to avoid the morning sun on those nights when she eventually fell asleep around dawn, she had taken pains to ensure that the windows were covered.

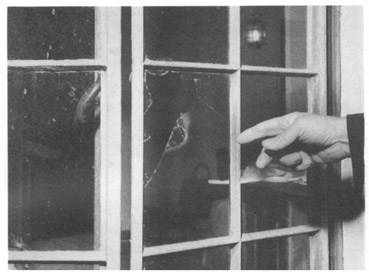

According to his contrived story, as relayed later to the police, Dr. Greenson asserted that he arrived and immediately took a fireplace poker and broke a window pane from his position in the garden, then claimed that he reached in and opened the window.

But there was a problem with that story: If he broke the glass pane from the outside, as he claimed, shards of broken glass would have fallen inside onto the bedroom’s carpet. But instead, shards of glass were found outside the house, on the ground, indicating that the glass had been broken from the inside.

Greenson altered Eunice’s story in another manner as well, claiming that he found Marilyn dead in bed with the phone’s receiver clutched in her hand, as if she were trying to call someone, whereas Eunice claimed that Marilyn was actually lying on the phone, positioned under her stomach.

It seemed that no one had carefully rehearsed their stories, a shortcoming that led to many discrepancies.

It would later be determined that if anyone wanted to gain entrance to Marilyn’s bedroom, all that he or she would have had to do was open the door over that thick, new, deep-pile carpet.

Eunice’s version of the timing of the events that transpired that night seemed so weirdly off that as the years passed, she would be asked to explain and re-explain the notable time irregularities of her various versions of what happened. “I think it was 3:30 or maybe 3:45am when I discovered the body. But it could also have been midnight.”

When pressed for information about the ambulance, she said, “I really can’t remember.” She also denied ever having called an ambulance, although company records later revealed that a “Norman Jeffries” had made the urgent call for one to be sent.

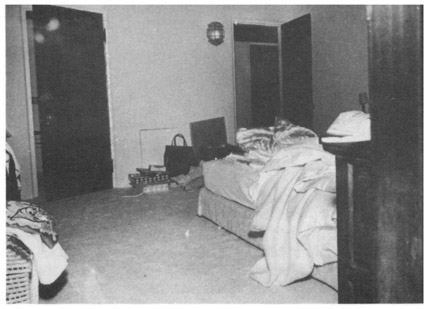

Crime Scene: Marilyn’s bedroom on Fifth Helena Drive

She also claimed that she had been the one to call Dr. Engelberg, but Dr. Greenson said he was the one. Engelberg later said it was Eunice who had phoned him. At one point, Eunice said that it was she, not Greenson, who had taken the poker and broken the window.

Dr. Greenson also got his time frames confused, at first claiming he was called to the house “at around midnight,” although Hall had reported him there at 10:30pm. If he had arrived at midnight, or even before, the question put to him was why he or Dr. Engelberg had waited so long to call the police.

What happened between midnight and 4:25am?

Engelberg had signed the death certificate at 3:50am.

Greenson, like Eunice, changed his story, claiming that he arrived at 3:30am.

As investigative reporter Matthew Smith later wrote: “That meant that Dr. Greenson was claiming that he dressed and drove to Fifth Helena Drive, then called Engelberg, who dressed and drove there, examined the body, and signed the death certificate—all in the space of twenty minutes. This was quite impossible.”

None of the eyewitnesses that night would emerge as pillars of consistency, frequently changing the time frames in response to challenging questions.

Later in her life, Eunice would finally admit that she lied on the night of Marilyn’s murder. When she got around to writing a highly unreliable memoir, Marilyn: The Last Months, published in 1975, she changed her story once again.

She admitted that she had seen no light nor any telephone cord under Marilyn’s bedroom door, a believable scenario because of the high pile of the newly installed carpet.

Seven years later, during an interview with researcher Justin Clayton, she came up with another story, saying that the door was found ajar, and that she walked right into the room. “It wasn’t necessary to break any window. I don’t remember how that window got broken. Maybe some kid threw a rock into it.”

At this point, all reference to a broken window as the means of access to Marilyn’s bedroom had been diminished to the status of a “red herring.”

But who, and when, and why, really broke the window?

***

It was a dull Sunday morning at the station house of the western division of the Los Angeles Police Department. The time was 4:25am on Sunday morning, August 5, 1962. A burly police sergeant who wore black-rimmed glasses, Jack Clemmons, was about to have his fifteen minutes of fame. Actually, his fame would last far longer, since journalists would still be writing about him during the 21st Century.

“It had been a dead night,” he later recalled. “Absolutely dead. Not even the cockroaches in the station house were moving about. Normally, I didn’t take incoming calls, the desk did that. But I was standing outside at the front entrance when I heard the phone ring. I don’t think we’d had a call all night. I picked up the receiver and heard this rather cultured voice.”

“This is Dr. Engelberg. Marilyn Monroe is dead. She committed suicide.”

“At first I thought some jackass was calling in as a prank,” Clemmons said. “Probably drunk after a wild Saturday night. But I took down the particulars and decided to drive over myself. If the call was legitimate, the world would be descending on Fifth Helena Drive.”

“Even as I drove there, I still thought it was a hoax,” Clemmons continued. “We’d received those calls before. The year before, a call came in that someone had shot Lana Turner, and that she was dead.”

“When I got to Marilyn’s home and rang the bell, this rather ugly, black-haired, late middle-aged terror opened the door,” he said. “She identified herself as Eunice Murray and told me she was Marilyn’s housekeeper. She said the call was genuine. Marilyn Monroe had been found dead in her bedroom.”

Clemmons would later recall, “It was a gut instinct, but I felt I’d arrived at the scene of a murder. This story was going to be big. I mean, really big. I asked the witch who else was in the house.”

“Dr. Greenson and Dr. Engelberg,” she said.

He would later learn that her son-in-law, Norman Jeffries, had spent the night in the murder house. “He was nowhere to be seen. I was told that Murray didn’t want him to talk to the police, and had asked him to leave before people started to arrive. This was the beginning of her lifelong concealment of what actually happened that night.”

“When did these two doctors arrive here?” Clemmons asked Eunice.

“Around midnight,” she told the sergeant, the first installment in her frequently changing timetables over the decades.

“I was shown into Marilyn’s bedroom, where the body was,” Clemmons said. “These two doctors were there. They were introduced to me, but when I offered to shake their hands, they didn’t respond. Engelberg was identified as Marilyn’s personal physician. He was rather slender, late middle age, and gray haired.”

“Greenson was introduced to me as Marilyn’s psychiatrist. He seemed to have been designated as the spokesman. He was a bit taller, with a drooping mustache. His gray hair was rather thin, and he had the darkest rings around his eyes. Both of them stood about six feet from the corpse on the bed. It was obvious to me that they resented my presence.”

“Marilyn’s blonde head was clearly visible above a white sheet,” Clemmons said. “I would have recognized her anywhere. I didn’t pull the sheet back to expose her nudity. I’d seen plenty of that. In the toilet at the police station, we had her nude calendar on the wall. I didn’t want to touch anything, including the phone. I felt that some ghouls had already done that for me. Her body was artfully arranged by someone. It was obvious to me that this was a staged event.”

“Her legs were arranged perfectly, as if she was getting ready to pose for another nude calendar. I had been at suicide scenes before, especially when the victim overdosed on barbiturates. In the last minutes before consciousness is lost, there is a great pain and the body contorts.”

“I asked Engelberg if he’d moved the body. He told me, ‘only to determine if she were dead.’ I thought he was lying. He was definitely hiding something. I later found that this Murray woman was washing bed sheets. Why? At this hour of the morning? I felt that the scene of the crime had been tampered with. But it was not my job to be the investigative officer on this case.”

“It was an eerie scene at the house that night, with the most famous woman in the world lying nude and dead in the bedroom,” Clemmons said. “I felt that vital evidence had been concealed or even destroyed. It was just a hunch. Everybody was acting so suspiciously I felt that, unlike Marilyn, they were unskilled actors not trained as either a liar or a cover-up artist. Murray was one little busy bee running around straightening up things until I asked her to stop.”

“‘Was there a suicide note?’ I asked Greenson.

“No note,” he snapped.

“Before superior officers arrived, I spent an hour and a half going over the scene, looking for clues,” Clemmons said. “There were empty bottles of prescription drugs by her nightstand.”

Greenson volunteered that, “She must have swallowed all the pills.”

“Where is the glass of water she used to swallow that many pills?” Clemmons asked. “I looked around; the doctors looked around—no glass. I went into the bathroom. It didn’t have one glass or cup. I turned on the water. Not one drop. Murray told me that the water in Marilyn’s bathroom had been temporarily cut off during a restoration of the house. She had to use the other bathroom at the end of the hallway.”

Greenson had followed Clemmons into the bathroom and said, “It was definitely suicide.”

“I turned to him and I was annoyed. Why don’t we let the Los Angeles coroner decide that?”

“As I listened to their contradictory stories about how her body was discovered, I wondered why they’d waited for more than four hours to call the police.”

“This Murray creature was very evasive, but so were the two doctors,” Clemmons said.

“We were talking things over,” Greenson said, according to Clemmons. “The people at Fox had to be notified because Marilyn was such a big star—the press, you know.”

“That was his fucking answer as to why he’d waited four hours to call the police,” Clemmons said. “He knew he was required by law to notify us at once.”

“Attitude is important,” Clemmons said. “Engelberg was polite, but this Greenson creep was very antagonistic. Each of his answers was sarcastic. I’d later learn that he was a communist. No one volunteered information. They gave only the briefest answers to my questions.”

“My time at the house had come to an end,” Clemmons said. “My relief, Sergeant Marvin Iannone, arrived. He told me that the detective who would take charge was on his way. Sergeant Iannone…that is a story for another day.”

Within moments, Sergeant Robert Byron came in to take over,” Clemmons said, “I drove back to the station. I was left with the impression that I had just interviewed three fucking liars. More than that, I believed there had been other people there during those missing four hours before the police were called. A lot of people had come and gone, but had cleared out before I got there. What were they covering up? The answer was most obvious to me: Marilyn Monroe was murdered!”

Back at the station house, Clemmons placed a call to a fellow police officer, James Dougherty, Marilyn’s wartime husband, her first.

“Marilyn is dead,” Clemmons told Dougherty. I’ve just come from her house. There were a couple of doctors there. They say it was a suicide.”

“They finally got her,” Dougherty said, without explaining who “they” were.

Clemmons later said that he began to realize some massive cover-up had begun when he read the Monday newspaper. “My call to Dougherty was reported in the press. But I heard what he told me. He said, ‘They finally got her.’ Guess what was reported in the press? He was quoted as turning to his new wife and saying, ‘Say a prayer for Norma Jeane. She’s dead.’”

***

Arthur Jacobs tried to reach Jack Clemmons at the station house, but found the phone constantly busy. By Sunday at around noon, reporters had learned of Marilyn’s death, and the phones were constantly ringing. Perhaps Jacobs wanted to vet Clemmons to see if he’d learned anything damaging during his visit to Marilyn’s house.

His entire staff had been summoned. “We’re in damage control,” Jacobs told them “The whole world wants to know. We’ve got to deal with the press. Marilyn’s death will make Second Coming headlines. Our official storyline is suicide.

”Because of the time difference, the residents of Japan were among the first mass of people to learn of the death of this fabled goddess.

In London, there were tragic consequences almost immediately. On learning of Marilyn’s death, British actress and Mayfair hostess actress Patricia Marlowe, 28, swallowed sleeping pills, which led to her death. Unlike Marilyn, she left a suicide note that read, “I want to die like Marilyn.”

Also in London, Gerdi Marie Havious, a dancer, turned to her husband, and asked, “Why did she do it?” Then she ran across her living room and leaped to her death from an open third floor window, impaling herself on a jagged iron gate.

In Mexico City, three teenage girls dangerously injured themselves during their attempts to commit suicide. There were other disasters as well, as much of the world received the news in stunned disbelief.

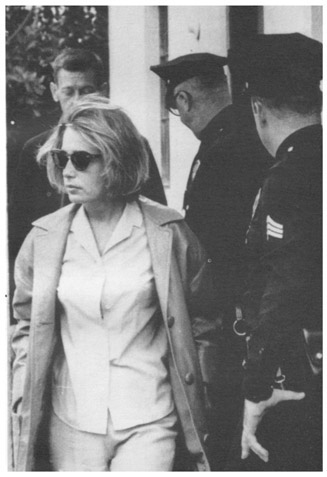

As dawn broke over the murder house, reporters and paparazzi, summoned early from their beds, were arriving at the scene. One unidentified woman, dressed in a raincoat and pajamas, was seen running from the house, screaming at the press, “You vultures! Murderers! Murderers! Are you satisfied now? You’ve killed her!”

Pat Newcomb and Norman Jeffries (behind her) being escorted out of Marilyn’s house by two policemen

This woman was later to be identified as Pat Newcomb. Such an outburst may have led to her firing. This was hardly the way Jacobs wanted one of his publicists to face the nation’s press.

Sergeant Marvin Iannone asked Eunice Murray when Marilyn Monroe’s bodyhad been discovered. Unlike what she’d told Clemmons, Murray told Iannone that she’d discovered the body at 3:45am. When confronted with earlier statement that it was at around midnight, she said, “I’m tired. My nerves are frazzled. Anybody can make a mistake.”

Iannone soon discovered the washing machine going full blast. When he inquired why she was doing this, Murray said that people would be arriving at Marilyn’s Brentwood home, photographs would be taken, and she wanted “everything to be neat and tidy.”

Then he asked her a potentially incriminating question. “That sheet over Monroe looks like it just emerged from the linen closet. Is it the same sheet over her body when you discovered her?”

“No, it’s a fresh one.”

“Did you remove a soiled sheet and put on a fresh one?”

Eunice burst into tears. “Please don’t pressure me. I’m half out of my mind. How can I possibly be expected to remember such a trivial detail?”

Detective Sergeant Robert E. Byron was the ranking officer on the scene. Aiding him in the initial investigation was Don Marshall, a plainclothes detective in the West Los Angeles division of the Los Angeles Police Department. Both of them searched the house for incriminating evidence. In the guest cottage, they discovered that the lock had been broken on a three-drawer filing cabinet.

All the contents of each drawer had been removed. Only one letter remained. It was from a nightclub in Paris, offering Marilyn a contract for her to appear for a one-week revue.

The door to the guest cottage opening onto the street was slightly ajar, but its lock had not been tampered with. Byron assumed that the theft had been an inside job.

Beginning that very day, Byron would be attacked for his “superficial investigation,” although he was considered one of the best detectives in the Los Angeles area. Over the years, it would be speculated that pressure was put on him by William H. Parker, the Los Angeles Chief of Police.

Parker was one of the leading supporters and friends of Bobby Kennedy in California. It was no secret that Parker wanted the Attorney General to name him as the replacement for J. Edgar Hoover at the FBI.

It seemed logical that to curry favor with Bobby, he would not pursue too vigorous an investigation into the death of Marilyn. He had actually been heard talking to Bobby in San Francisco that Sunday morning, and he knew that the Attorney General had been at Marilyn’s house that Saturday afternoon.

Allegedly, Bobby told him, “Seize Marilyn’s phone records before Nellie Hoover gets her hands on them. She’ll try to use them to blackmail me.”

In a daring move, Parker knew he could save Bobby a lot of embarrassment and political damage if the police seized those records instead of the FBI. He authorized two of his policemen to bring the records back to his office.

A bit later, in Washington, Hoover realized that the phone records might contain lots of last-minute calls to Bobby, or even to the President, and could be very damaging to them. He ordered his agents in Los Angeles to seize Marilyn’s phone records. But when Hoover’s agents arrived at the phone company, they were told that the records had already been confiscated by the LAPD.

Once the records had been delivered to Parker’s office, he reviewed them and then ordered a special courier to deliver them at once to the office of the Attorney General in Washington—“For the eyes of Robert F. Kennedy only.”

Hoover never spoke to the Attorney General about the death of Marilyn, but he did discuss it with close friends, including his lover, Clyde Tolson, and with another agent, Guy Hotell, and his “gal pals,” Dorothy Lamour and Ethel Merman. “Monroe was murdered,” Hoover claimed. “It was not a suicide.” He chose not to reveal how he knew that or who had actually murdered her.

Back in Hollywood, Jacobs was already hearing what key figures in the entertainment industry were saying about Marilyn. Elizabeth Taylor told the press, “It could easily have been me.”

Marilyn’s final director, George Cukor, said, “Marilyn was not a lady who would have taken aging well. Her forties would have been a horror for her. She didn’t have the integrity of a true actress—she would not have welcomed the riches of character interpretations, as a true actress would have. She was a star trading on certain gimmicks, and in her heart she knew that.”

***

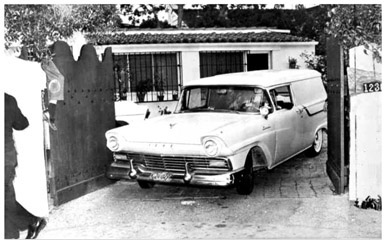

Back at the murder house, someone (it was never made clear who) placed a call to Guy Hockett and his son, Don, the owners of the Westwood Village Mortuary. They were asked to drive to Marilyn’s home to remove her corpse.

Arriving in a battered white van, they were ushered into Marilyn’s bedroom, where they ordered everybody out.

“We were told that she’d been dead for only an hour or two,” Guy said. “That was pure bullshit. Rigor mortis had set in. She’d been dead for hours. We had a hell of a time bending her arms and legs, trying to fit her onto our gurney to move her outside and into the hearse. We had to do quite a bit of bending to get the arms into position so that we could, you know, put the straps around her.”

Although he was not a doctor, Guy was familiar with signs of mostmortem lividity, which is a bluish-purple discoloration of the underside of a corpse. This is caused when blood settles downward as a result of the pull of gravity. “Lividity takes several hours to develop,” he said. “She had this discoloration on her body. Her fingernails had turned completely blue, like she had put blue nail polish on them. Somebody lied. We suspected a cover-up.”

William Parker, Chief of the Los Angeles Police Department

Covered in a pink woolen blanket—pink had been her favorite color—Marilyn’s corpse was strapped onto that steel gurney and hauled out of her home in full view of the near-hysterical cabal of reporters and paparazzi who had rushed to the scene of the murder. They slid the body inside the Ford van and slammed the door, as photographs were madly snapped.

Presumably, in high-profile cases such as that of Marilyn, or in cases where the death of a person is suspicious (often involving young men or women), the body is delivered to the coroner’s office in downtown Los Angeles. But for some surprising reason, Marilyn’s corpse was sent to the nearby mortuary.

Her body was there for two hours and left unguarded in the back of the mortuary, except for an attendant whose name is not known.

Even as the body lay there, awaiting an eventual autopsy which would be ordered, the most ghoulish part of her legend was about to unfold.

Today, it’s dismissed as “just an urban legend,” but many of Marilyn’s fans still believe that her body was “violated” before an employee of the coroner’s office arrived to claim the corpse.

In Los Angeles, as in many large cities, unscrupulous employees in funeral parlors sometimes make deals with necrophiles when a dead body of a young man or young woman is brought in.

Necrophiles sometimes go for a year—or a lot more—without sexual relief and will often pay top dollar to have sexual intercourse with a recently dead corpse. The body of Marilyn Monroe would be among the most celebrated in the world for violation after death.

Before her funeral, word had spread that five necrophiles made a financial deal with some attendant at the mortuary and were allowed to spend time with Marilyn’s corpse, paying $1,000 each for the privilege of “seducing” her, postmortem. That was a lot of money back in 1962.

The Hocket s were gone at the time on other business, and would have been unaware of such an outrage, even, indeed, if it were true.

Urban legend or not, the rumor has legs and the alleged violation of Marilyn’s body still has its believers.

Dr. Greenson was once asked about this rumor by David Garrison, a reporter from The Los Angeles Herald-Examiner. “That’s so disgusting. I can’t even contemplate such a thing, although I’m aware of the practice. If it’s true, and I don’t believe it for a moment, it would be the final, the ultimate, violation of poor Marilyn. She led such a painful, troubled life. If only she could rest in peace. But no, I don’t think the jackals will let her do that.”

The van with Marilyn’s body drove through a growing crowd of reporters and photographers.

“Whether that horror is a fantasy or not, Marilyn is still being spiritually violated, and her reputation forever destroyed,” Greenson said. “Perhaps a hundred years from now, people will still be talking and wondering about Marilyn. She’s going to enter that special Nirvana of goddesses like Cleopatra and Helen of Troy.”

Garrison’s question and Greenson’s comments were never printed in L.A.’s Herald-Examiner, Garrison’s editor claiming, “This newspaper has to maintain some degree of integrity and decency, and there’s no proof.”

However, an underground newspaper, Sleaze, distributed mainly on Hollywood Boulevard, picked up the claim and printed it in August of 1962 for the titillation of its sensation-seeking but limited numbers of readers.

Back then, the story was suppressed, but today, based on today’s more permissive standards, it might merit banner headlines in tabloids distributed at supermarkets to millions of shoppers.

***

Lionel Grandison, the deputy coroner’s aide for the County of Los Angeles, was charged with ensuring that persons who died under questionable circumstances should have their bodies sent first to the city morgue for an autopsy.

At first, he wasn’t even sure where Marilyn’s body was until he found out from Sergeant Iannone that it had been sent to the Westwood Village Mortuary.

When he arrived there, he discovered that the on-duty staff was already preparing the body for embalming. He later said, “The guys there squawked and didn’t want to release the body in my custody, but the law was on my side.”

Marilyn, post-mortem

As the hearse carried her to the county morgue, Grandison listened to the radio. He heard the voice of Peter Lawford, who said, “Pat and I loved her dearly. She was one of the most marvelous and warm human beings I have ever met. Anything else I could say would be superfluous.”

In New York, Susan Strasberg told the press, “Marilyn was called an iron butterfly. Butterflies are very beautiful, give great pleasure, and have very short lifespans.”

“The Sunday morning newspapers across America had been put to bed before the announcement of Marilyn’s death. The radio revealed that it was a young reporter, Joe Ramirez, who scored a world class scoop. He’d actually been on a death watch for the distinguished actor Charles Laughton, who was said to be dying. Actually, the British star would live until December of that year.

Ramirez had arranged for a contact within the LAPD to notify him of Laughton’s death. But his source called during the early hours of Sunday morning and said, “Marilyn Monroe is dead.”

Ramirez had rushed to the office of the City News, a small news agency, and had moved the startling news across the wire. It was flashed around the world. Most Americans first heard the news over radio. No one could reach Joe DiMaggio for comment. Nor could they locate Arthur Miller. In France, Yves Montand received a string of eighteen calls that came in from news agencies around the world.

Columnist James Bacon, who had once had a brief affair with Marilyn, was the first reporter to file an eyewitness report. Tipped off by a policeman, he’d rushed to Marilyn’s house and barged in. When a policeman confronted him, he claimed he was from the coroner’s office. He managed to get inside her bedroom before he was evicted. But he’d learned enough to file his story.

Grandison’s boss was the controversial Los Angeles coroner, Dr. Theodore Curphey, who, bowing to pressure, had ordered a last-minute autopsy on Marilyn’s corpse. He’d instructed that her body be transported to the basement of the dank and rat-infested basement of the Hall of Justice on Temple Street in downtown Los Angeles. The world’s most famous goddess had been designated as Case No. 81128 and placed into Crypt 33.

The morgue in L.A. had a notorious history of corruption, graft, and mis-management.

Assigned to the case to perform the actual autopsy that Sunday morning was Dr. Thomas Noguchi, a Japanese-born surgeon who had moved to the United States in 1952. He’d studied pathology at the Orange County General Hospital in California, and in 1960 had taken a position with the coroner’s office. In time, he would be elected president of the National Association of Medical Examiners.

But when his knife cut into Marilyn’s brain, he was still only a junior member of the staff.

In time, he would perform autopsies on the bodies of Sharon Tate (murdered by one of Charles Manson’s crazed killers), Janis Joplin, William Holden, John Belushi, Sal Mineo, and Natalie Wood after her body was brought to him after she’d drowned off the coast of Catalina Island. He would later write a controversial memoir, Coroner.

Ironically, about six years later, on July 6, 1968, it was the same Dr. Noguchi, then the chief medical examiner for Los Angeles County, who performed the autopsy on Robert Kennedy after his assassination at the Ambassador Hotel.

John Miner of the Los Angeles District Attorney’s office would be assigned as a witness to watch Noguchi’s work on Marilyn. Miner later claimed he was profoundly shocked when he first saw Marilyn’s nude body. “This young, young woman looked as if she could get up off the table and walk away at any moment.” Then Noguchi’s cutting began.

In one of the most controversial reports from Noguchi, he claimed that he had gone over Marilyn’s body, checking every millimeter for signs of an injection, but had found none. Conspiracy theorists who included Robert Slatzer were infuriated with this claim. Even after Marilyn was buried, he maintained that her corpse should be exhumed and her rib cage examined, because James Hall, the ambulance driver, had seen Dr. Greenson inject her, using a large needle, under her breast.

While exploring her body, Noguchi did not even find the injection mark that her physician, Dr. Engelberg, had given her the day before her death. Others claimed that the mark from Engelberg’s injection would have healed before Sunday morning, although that wouldn’t be the case with Greenson’s injection.

Dr. Engelberg had also reported that he had prescribed twenty-five Nembutal capsules to Marilyn on Friday. That prescription was filled the day before Marilyn died, as confirmation with her local pharmacist revealed.

Another controversial claim the autopsy revealed was that her stomach was empty. No traces of Nembutal or any other drugs were found there. The colon, however, showed marked congestion and purplish discoloration. To Miner, the discoloration of her colon indicated that foul play had been involved in her death.

At the time, Noguchi was relatively inexperienced and unfamiliar with the criminal use of enemas or suppositories, although in 1962, they were in use by the KGB, the Mafia, and the CIA.

Noguchi opened her chest and removed her rib cage as a means of examining her chest organs. If James Hall’s report were accurate, Dr. Greenson’s needle mark would have been noticed as slight damage to the rib cage. Grandison later claimed that he felt vital data was suppressed in the final autopsy report he was given to sign.

Within days, Miner would write a controversial memo, contradicting many of Noguchi’s conclusions. “Without a more thorough examination, we could reach no conclusion as to how Marilyn died,” he wrote in his memo.

The autopsy revealed a large bruise on the lower left backside of her hip area, but Hall had accounted for that when he claimed he’d dropped her body in the guest cottage.

Many critics attacked the suggestion of a drug-laced enema, yet no authority has ever disproved it, either. Miner would later interview some of the most famous pathologists in the United States. His final conclusion—not stated in Noguchi’s report, read: “It seemed to me that in all likelihood, the route of the administration of barbiturates was by means of an enema that was very slowly administered and that contained barbiturates.”

When Miner was asked if he thought Marilyn was murdered, he replied, “I think that’s more probable than not.”

Noguchi’s report was leaked to the press. It made dull reading, but voyeurs were particularly interested in the coroner’s report on her vaginal area.

He claimed her external genitalia “shows no gross abnormality, and the distribution of the pubic hair is of female pattern. The uterus is of the usual size. No polyp or tumor is found. The cervix is clear. A vaginal smear is taken.”

Rumors spread that Marilyn’s vagina contained deposits of semen, suggesting that with in the past twelve hours or so she had been penetrated. But then, counter rumors were spread that her vagina had been washed out before it had been committed to the morgue. That fueled speculation that she had been raped, postmortem, by necrophiles, and that someone had attempted “to wash out” her vagina with cleanser before her corpse was moved to downtown L.A.’s morgue for the autopsy.

Lionel Grandison

Theodore Curphey

Thomas Noguchi

After his five-hour examination of the corpse, Noguchi removed her kidneys and intestines for further study. He announced at the time, “These specimens are vital in determining the mode of death. Without them, we can only indulge in speculation.”

The specimens were turned over to the morgue’s chief toxicologist, Raymond J. Abernathy, who ran tests only on the blood and liver, not the other organs removed. The blood tests revealed heavy traces—each of them well above what would have been fatal—of Nembutal and chloral hydrate, the latter the key ingredient in the notorious knockout drug “Mickey Finn.”.

When Noguchi, days later, approached Abernathy for the test results, he was shocked when he was told that the body parts had been disposed of because Abernathy felt that no other tests were needed.

Noguchi anticipated that the fact that specimen had been discarded would cause an uproar in the press, and it did. The question was asked, repeatedly, “Why would such vital evidence from the most famous corpse in the world at that time be routinely disposed of?”

Conspiracy theories associated with Marilyn’s death were launched.

Years later, Miner would proclaim, “In all my years as deputy district attorney, organ samples of victims would mysteriously disappear only twice—once in the death of Marilyn Monroe in 1962, and again after the autopsy performed on Robert Kennedy in 1968.”

It was suggested that Abernathy listened to a higher authority, “God and Chief Parker.

”Soon, another outrage became apparent: Each of the medical pictures taken during the autopsy had also disappeared. No investigation was ever launched as to who stole these gruesome photographs.

The autopsy report came under fire from points throughout the nation. Journalist Anthony Scaduito referred to it as “one of the weirdest autopsy reports ever confected.” Dr. Sidney B. Weinberg, chief medical examiner of Suffolk County, New York, claimed, “The evidence points to all the classic features of a homicide, much more so than a suicide.”

Robert Slatzer called the official report a fake. He charged that the actual autopsy report had been suppressed and a fraudulent copy substituted, leaving out vital data that would have revealed that Marilyn was murdered.

On the Sunday night of Marilyn’s death, Leigh Wiener, a photographer for Life magazine, entered the Los Angeles County Morgue and gave the guard three quarts of the most expensive Scotch money could buy.

In return, the guard wheeled out Marilyn’s body. A card tied to her left big toe identified her as “MARILYN MONROE—CRYPT 33.”

Wiener snapped several pictures. At one point, he removed the white sheet and snapped frontal nudes of her body, the way it looked after surgery. Her celebrated breasts were flattened.

A postmortem facial photograph of her was flashed around the world. As Marilyn herself might have said, “I didn’t look camera ready.”

County Coroner Dr. Theodore Curphey, Noguchi’s supervisor, announced that it was his “presumptive opinion” that Marilyn’s death was caused by an overdose of Nembutal capsules. In spite of overwhelming pressure, he said in his judgment that no formal inquest was needed. He did say, however, that he had appointed a Suicide Prevention Team to look into the star’s mental condition at the time of her death.

His comments did little more than ignite conspiracy theories regarding Marilyn’s death—suicide or murder?—that would still be raging during the 21st Century.

***

Like the rest of the world, Frank Sinatra learned of Marilyn’s death on Sunday morning when he woke up early. For reasons of his own, he immediately placed a call to Ava Gardner in Madrid, who had not heard the news. “I always suspected that she would eventually do herself in,” Ava said.

He astonished her by telling her, “Marilyn didn’t kill herself. She was murdered.”

“I can’t believe that,” she said. “Who did it?”

“I’m not sure, but I intend to find out,” he said. Before ringing off, he made a vow over the phone. “When I find out the son of a bitch who killed her, I’m going to kill him myself.”

She warned him, “Be careful. You might be the one who ends up getting killed.”

“Honey, if Frank Sinatra had ever been careful, he would never have left Hoboken.”

Deeply saddened by the news of Marilyn’s death, Sinatra went into a deep, morbid depression. He told Sammy Davis, Jr. and Dean Martin that he had planned to marry Marilyn. Whether that was true or not is not known.

Two weeks later, Sinatra placed another call to Ava in Madrid. “I’ve learned who killed Marilyn. I know who the bastards are.”

“Who?” she asked. “Who are you talking about?”

“I can’t tell you,” he said. “It’s dangerous for you to possess such information, and your phone might be tapped. But I promise you this, if it’s the last thing I do on this earth, I’m gonna bring the bastards down. One by one. That’s how I’ll get them. And not a one of the shits will know I was behind their down-fall.”

That very next weekend, Sinatra called Bobby Kennedy, a man he detested, at the Justice Department. Through some connection, Sinatra had learned of the indirect involvement of Sam Giancana and the direct involvement of Johnny Roselli. He even knew who the killers were.

“The one thing I can’t find out is who paid Giancana to carry out this murder, unless he did it on his own,” Sinatra informed Bobby.

Bobby promised Sinatra that he’d look into it. But he never did, no doubt fearing that an investigation would reveal his own tortuous links to Marilyn.

It is pure speculation but Bobby perhaps knew a lot more than he ever revealed about who was the power behind Giancana during the plotting of Marilyn’s demise. That “smoking gun” has never been discovered.

***

Marilyn’s body was once one of the most sought-after in America, but after her death, an issue arose about who would claim it. At Rockhaven Sanitarium, in Norwalk, California, Gladys Baker Eley was sixty-two years old and incompetent. She couldn’t even look after herself, much less dispose of her daughter’s body.

DiMaggio was devastated when he heard the news of Marilyn’s death. “Suicide, hell. She had our future life together. We were going to remarry. It was the fucking Kennedys, that Bobby in particular. I hate him. And that fucking bastard Sinatra. I’m through with him. He was part of the plot to murder Marilyn.”

DiMaggio flew from San Francisco to Los Angeles. Once there, he was able to reach Marilyn’s half sister, Bernice Baker Miracle, in Florida, who authorized him, in lieu of Marilyn’s family, to make the funeral arrangements. Bernice told DiMaggio, “I think it was definitely not suicide. I don’t believe that Marilyn deliberately took her own life.”

Whitey Snyder, Marilyn’s longtime friend and makeup artist, was assigned the task of making her corpse ready for an open casket viewing. His new wife, Marjorie Plecher, helped him.

Weeks before she died, Marilyn had made Snyder promise something: “If something happens to me, you won’t let anybody touch my face but you, will you?” He promised that he’d be there for her.

When Snyder arrived for the final makeup, he discovered that a heartbroken DiMaggio had spent the night by her side. “His eyes were red from weeping, and he was transfixed, gazing at her,” Snyder said. “It was a bit eerie. I think he blamed Hollywood for her death—Hollywood and the Kennedys.”

After the autopsy, Marilyn’s breasts were flat. “She would never want to be exposed with a flat chest,” Snyder said. Both he and Marjorie tore up a cushion and used the stuffing to give her a faux bosom.

Sidney Guilaroff, her favorite hairdresser, was summoned to arrange her hair, but he collapsed in the mortuary and had to be helped out of the building.

In desperation, Snyder retrieved the wig she’d worn in The Misfits and artfully arranged it on her head. Of the dresses brought to him from Marilyn’s home by Eunice Murray, he and Bernice Miracle selected the pale green Pucci she’d worn at her press conference in Mexico City.

As Marilyn’s body was prepared for viewing, the most aggressive members of the press, at least some of those who were aware of Marilyn’s links to the Kennedys, tried to get comments from key figures within her orbit, including Jack, Jackie, and Bobby. Her closest friend, Patricia Kennedy Lawford, had no immediate comment, and Peter Lawford had mysteriously left the scene for Hyannis Port.

The First Lady had no intention of issuing any comment about Marilyn. She wisely fled from Washington, departing with her children on August 7 for an extended trip to Europe.

The President was in Maine, having a vacation at the retreat of former heavyweight champion, Gene Tunny, on John’s Island. He was seen sailing on a Coast Guard yacht named Manitou.

The most speculation centered on the whereabouts of Bobby Kennedy, who had seemingly disappeared into the wild mountains of Oregon.

Arthur Miller was in New York, but was not taking phone calls from reporters.

Miller was working on After the Fall, a play based on his marriage to Marilyn. “A suicide kills two people,” was one of the most memorable lines of the play, which would have its New York premiere on January 23, 1964. The character of Quentin (based on Miller himself) speaks that line to Maggie, the blonde star.

The play was directed by Marilyn’s former lover, Elia Kazan. The poet, Norman Rosten, who had been a friend to both Miller and Marilyn, denounced the playwright for depicting her as a slut.

***

Marilyn’s funeral was scheduled for April 8, 1962, in the Chapel of Palms at Westwood Memorial Park. The glitterati of Hollywood were adorning themselves for what was rumored to be the greatest funeral in Hollywood since the tragic early death in 1926 of the silent screen idol, Rudolph Valentino.

Westwood Memorial had seen better days. Even during its heyday, it was never as prestigious as Forest Lawn, where Marilyn’s many friends and fans had expected her to be buried.

Perhaps Westwood was chosen because Marilyn’s former guardian, Grace Goddard, and her favorite aunt, Ana Lower, were entombed there. Marilyn had always maintained that Grace and Ana, not her mother Gladys, were the only people who had shown any love toward her when she was a child.

Westwood Memorial looked a bit seedy, tucked behind Wilshire Boulevard in a dull neighborhood of stucco homes. The grounds were not well maintained and the pink paint on the mausoleum was peeling. The roar of traffic on the west side of Los Angeles could be heard day and night. It was not a very restful place.

At the last minute, the film colony’s most prestigious members, including George Cukor and the executives at Fox, were informed that attendance at her funeral would be by invitation only, with a very limited and abbreviated guest list. Learning that they couldn’t attend, many directors, executives, and stars sent masses of flowers, mostly pink carnations and tuberoses, which were said to have been her favorite flowers.

To all the people who wanted to personally pay their respects, DiMaggio issued a brief statement: “This will be a small funeral, so she can go to her final resting place in the quiet she always sought.”

The cameras were turned on to catch DiMaggio and his son, Joe Jr. arriving at the shabby memorial building. The senior DiMaggio was in a flawlessly designed business suit and his son was in full dress Marine uniform.

Other guests included Dr. Greenson and his family; Anne Karger (mother of Marilyn’s first “great love,” Fred Karger; Inez Melson (Marilyn’s business manager); Marilyn’s half sister, Bernice Miracle; Pat Newcomb; Eunice Murray; her masseur, Ralph Roberts; her lawyer, Mickey Rudin; her hair stylist, Sidney Guilaroff, and both Paula and Lee Strasberg.

Other wannabe guests, some of the most celebrated names on the planet, showed up but were turned away.

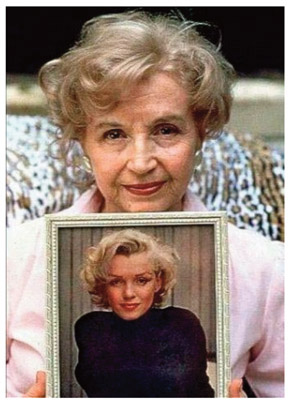

Remembering Marilyn: Bernice Baker Miracle

Frank Sinatra and many of his friends, who had always been close to Marilyn, decided to go anyway, even though they hadn’t been specifically invited. “That bastard, DiMaggio, wouldn’t dare turn us away,” Sinatra told his gang.

DiMaggio later explained his snub of many of those people who were closely associated with Marilyn. “If it wasn’t for her so-called friends, Marilyn would be alive today.”

Ironically, while many of Marilyn’s friends were turned away, DiMaggio invited some of the key players who were accomplices in the cover-up of her murder.

Getting nautical: JFK

Arthur Jacobs objected to the guest list. “If Marilyn had been in charge of the invitations, half the people on the list would not have been invited, and more of her friends would have been included.”

To pay his respects to Marilyn, Sinatra was driven to her funeral in a limousine with Patricia Kennedy Lawford, who had flown across the country to attend. Her husband, Peter, had left town.

Both of them were turned away at the door by a security guard. Sinatra offered the guard one hundred dollars to let them in, but he refused. “No one blocks Frank Sinatra from anything,” he told the guard. “You’ll hear from me.”

To his surprise, he saw Ella Fitzgerald coming up the steps. He kissed her on both cheeks. “Ella, Marilyn admired you so much,” he told the singer.

“I loved that little gal,” Fitzgerald said. “She was so lost. I used to hold her against my bosom.” To her shock, the security guard also had orders not to admit her to the chapel, either. She burst into tears, as Sinatra tried to comfort her.

Furious, yet fighting back tears, Sinatra stood with Patricia and Sammy Davis, Jr. on a grassy lawn outside the chapel. Davis, too, had been barred. They listened to the sounds of a Judy Garland recording of Over the Rainbow, Marilyn’s favorite song.

***

When he’d flown to Los Angeles, DiMaggio had checked into the Miramar Hotel, near Marilyn’s home in Brentwood. During his first hours there, he was seen drinking heavily, waiting for his son, Joe Jr., to arrive from Camp Pendleton, where he’d been granted leave to attend the funeral.

During one of his dialogues with Marilyn’s lawyer, Mickey Rudin, DiMaggio said, “Bobby Kennedy is responsible for her death.” He said that loud enough for fellow patrons at the bar to hear him. At least one customer called The Los Angeles Times to report on DiMaggio’s accusation, but the item was interpreted as too incendiary to print, back in those relatively restrained days of the American press.

DiMaggio would never change his opinion of Bobby, and would carry his bitterness toward the Kennedys for the rest of his life. Three years later, at a charity game in New York City’s Yankee Stadium, Bobby showed up and wanted to shake the hands of the players. As a guest of honor, DiMaggio was in the receiving line. The Yankee slugger saw Bobby coming. When Bobby approached DiMaggio, the baseball star turned his back.

At the funeral, both of the DiMaggios, father and son, sitting up front, were in tears throughout the entire solemn proceedings.

Lee Strasberg was assigned the task of giving the eulogy. He and Marilyn had grown apart during the previous few months. The last time he’d flown to Los Angeles, he had not even come by to see her. If she’d survived until Monday, August 6, she was planning to eliminate him from her will.

In his selection of Strasberg to deliver the eulogy, DiMaggio seemed unaware that his relationship with Marilyn was no longer close.

Only hours before, attorney Mickey Rudin had informed Strasberg that he was the principal heir to Marilyn’s estate, “This more or less puts you in control of all future marketing of her image,” Rudin said.

In The MarilynFiles, Robert Slatzerwrote: “Some journalists have slyly hinted that the Strasbergs have been implicated in Marilyn’s death—that they may have killed her for financial gain. Ironically, Marilyn died broke. The expense of maintaining her lifestyle had drained her bank account dry.”

DiMaggios, father and son

In time, however, the estate would generate millions. By then, both Paula and Lee had died and would not benefit from it. Instead, the windfall went to a young actress, Anna Mizrahi, whom Lee had married after the death of Paula. She and her two sons now enjoy the Monroe millions, even though they did not know the star.

In time, Marilyn’s estate would be marketing inexpensive Marilyn Monroe dresses, even Marilyn Monroe toilet water and “Marilyn Wine,” which carried a slight taste of vinegar.

With his theatrically trained voice, Strasberg delivered the eulogy:

“Marilyn Monroe was a legend. In her own lifetime she created a myth of what a poor girl from a deprived background could attain. For the entire world, she became a symbol of the eternally feminine.

But I have not words to describe the myth and the legend. I did not know this Marilyn Monroe.

We, gathered here today, knew only Marilyn—a warm human being, impulsive and shy, sensitive and in fear of rejection, yet ever avid for life and reaching out for fulfillment.

Despite the heights and brilliance she had attained on the screen, she was planning for the future; she was looking forward to participating in the many exciting things which she planned. In her eyes and in mine, her career was just beginning. The dream of her talent, which she had nurtured as a child, was not a mirage…Others were as physically beautiful as she was, but there was obviously something more in her, something that people saw and recognized in her performances and with which they identified. She had a luminous quality— a combination of wistfulness, radiance, yearning— to set her apart and yet made everyone wish to be part of it, to share in the childish naïveté which was at once so shy and yet so vibrant.

Now it is all at an end. I hope that her death will stir sympathy and understanding for a sensitive artist and woman who brought joy and pleasure to the world.

I cannot say ‘good-bye.’ Marilyn never liked good-byes, but in the peculiar way she had of turning things around so that they faced reality—I will say‘au revoir.’ For the country to which she has gone, we must all someday visit.”

Anna Mizrahi Strasberg

Inside the chapel, DiMaggio waited for all the guests to file past Marilyn’s open coffin. Joe Jr., stood by his side. When most of the guests had paid their final respects, he placed three beautiful roses in her cold, dead hands.

Before the casket was lowered, he sobbed, “I love you! I love you! I love you!”

Joe Jr., moved toward the casket to kiss Marilyn like his father had, but the senior DiMaggio barred him

Perhaps the senior DiMaggio had heard disturbing stories about his son and his relationship with his late stepmother.

When a cynical Sinatra heard about DiMaggio’s theatrics beside the casket, he said, “Joltin’ Joe always said he and I would be friends until the end. This is the end.”

The legend—myth, really—was already growing as Marilyn’s body was entombed in the Corridor of Memories section of Westwood Memorial. Guards had to prevent crazed fans from attacking the tomb, as a hysterical race began for flowers, ribbons, and whatever else could be carried away from the event as souvenirs.

The body of Norma Jeane, the young model who set out to conquer Hollywood in the 1940s, was placed in a crypt behind variegated marble with a simple bronze plaque.

That night, by himself, Joe DiMaggio, Sr., returned to Westwood Memorial Park for his final farewell with Marilyn.

For the next twenty years, he ordered the weekly delivery of fresh red roses placed in the urn beside her crypt.

For reasons known only to himself, he cut off the deliveries in 1982.